Abstract

Entrepreneurship is the driving force behind the creation of rural employment opportunities and the promotion of the sustainable development of the rural economy. Based on the data of five rounds of national surveys covering the period from 2010 to 2018 conducted by the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), this paper uses probit and other regression models to empirically study the impact of internet use on the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers. The results show that the use of the internet can not only increase the probability of returned migrant workers starting a business but also increase the scale of entrepreneurial investment by 18% and the number of enterprises founded by 36%, which is particularly prominent among those rural areas with great potential for internet penetration. In rural areas with low levels of internet application, governments should continue to increase the level of support aimed at assisting returned migrant workers with founding their own businesses, to focus on enhancing the information literacy of returned migrant workers, and to accelerate the construction of information technology in rural areas with backward internet infrastructure to drive sustainable economic development through entrepreneurship.

1. Introduction

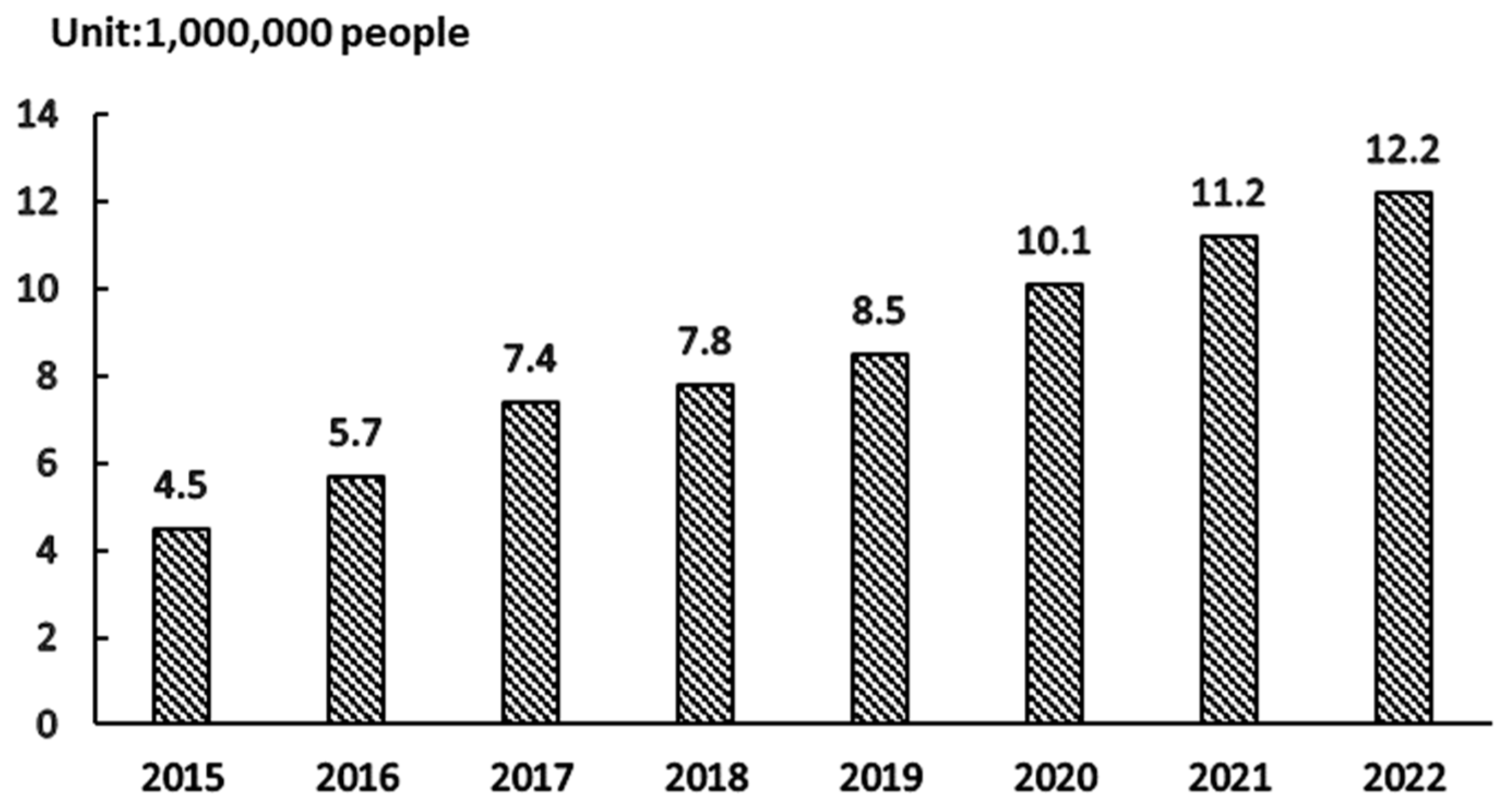

Employment is fundamental to ensuring the development of people’s well-being, and entrepreneurship is the driving force for sustainable economic development. Starting a business in rural areas not only generates employment opportunities for farmers and increases their incomes [1,2] but also helps to alleviate income inequality and poverty in rural areas [3,4,5], to promote the sustained, inclusive and sustainable development of rural areas and to create favorable conditions for the realization of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. As one of the countries containing the largest number of farmers in the world, China attaches great importance to entrepreneurship in rural areas. In 2015, the “mass entrepreneurship and innovation” initiative was included in China’s annual Report on the Work of the Government. In June of the same year, the State Council of China issued the “Opinions on Supporting Migrant Workers and Other Personnel to Return to Their Hometowns for Entrepreneurship to Start Businesses,” which aims at supporting migrant workers, college students and other personnel in returning to their hometowns to start businesses. Due to their familiarity with rural areas and their network advantages in their hometowns, migrant workers who have accumulated the necessary funds and experience for entrepreneurship have quickly become the main force behind rural entrepreneurship, and their numbers are constantly increasing. In 2015, there were 4.5 million people in China who started businesses in rural areas, but by 2022, the number of entrepreneurs in rural areas has reached 12.2 million, showing an average annual growth of 15.32% (Figure 1), of which 70% are returned migrant workers (In this paper, the term migrant workers refers to a social group that has been working in the city (within China) for many years or for most of their time, but whose household registration is still in the countryside. Returned migrant workers mainly refer to migrant workers who return to those rural areas, counties or townships where their hometowns are located to work and live there on a permanent basis.). According to the calculations of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China, on average, rural entrepreneurship projects can engage 6.3 farmers in stable employment, drive 17.3 farmers into flexible employment, and create new growth points both for increasing rural employment and promoting rural economic development. However, compared to China’s more than 500 million farmers, the portion of migrant workers who return to their hometowns to start businesses is still small. At the same time, due to the limitations of capital accumulation and business capacity, the entrepreneurial scale of returned migrant workers is relatively small, which is mainly reflected in the fact that returned migrant workers often only open a single enterprise, the scale of investment is small, and the ability to drive local employment and economic development still needs further improvement. The best way to stimulate the entrepreneurial enthusiasm of returned migrant workers and to expand both the scale of entrepreneurial investment and the number of enterprises set up by returned migrant workers to promote the comprehensive development of the rural economy and society has become a research theme of great theoretical and practical significance under the goal of achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Figure 1.

Number of returning entrepreneurs in China for the period covering 2015 to 2022. Source: China National Bureau of Statistics.

The spread of the internet has profoundly changed the way that farmers and rural areas develop. In the process of information dissemination and sharing, the cost of information searching has been reduced by proliferation of the internet, technological progress has been driven, and the long-term accumulation of human capital [6] has been promoted. The popularization of the internet also makes the diffusion of knowledge and information less expensive, which in turn promotes innovation and increases the effectiveness of innovation [7]. Internet finance has the characteristics of advanced technology, fast service and low cost [8], which are all conducive to changing the relatively backward financing environment of rural enterprises [9], and improving the financing capacity of rural enterprises. Has the use of the internet promoted the entrepreneurial decision-making of returned migrant workers? At the same time, what impact does the use of the internet have on the scale of entrepreneurial investment and the number of businesses established by returned migrant workers? To explore these issues, this paper takes data from five rounds of national survey data captured by the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) in 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016 and 2018 to identify returned migrant workers. By establishing a regression model, we analyze the impact of internet use on their entrepreneurial decisions and scale (including the scale of entrepreneurial investment and the number of businesses established) and focus on studying the impact mechanism of internet use on the entrepreneurial activities of returned migrant workers, which provides a new perspective for promoting the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers and improving the entrepreneurial level of rural areas.

Although the existing research explores the impact of internet use on the entrepreneurial decision-making of returned migrant workers [10,11], because of the timeliness of the data, it does not reflect the latest characteristics of the impact of internet use on returned migrant entrepreneurs following China’s accelerated period of returning entrepreneurship in 2015, nor does it deeply study the impact of internet use on the scale of the entrepreneurship practiced by returned migrant workers. This paper uses data from five rounds of national surveys of the CFPS to explore the impact of internet use on migrant workers’ who have returned to their hometowns to start businesses. Compared with the previous research, the contributions of this paper mainly fall in the following three aspects. First, it enriches the literature on the microeconomic effects of the internet and the influencing factors of returned migrant workers’ entrepreneurship and empirically tests the impact of internet use on the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers. Second, while studying the impact of internet use on the entrepreneurial decision-making of returned migrant workers, the impact of internet use on the scale of entrepreneurship is also discussed. Third, this paper uses the data of five rounds of national surveys of the CFPS, as the use of multiple rounds can more profoundly reflect the changes in China’s level of entrepreneurship among returned migrant workers since 2015, and explores the impact of internet use on the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers in the new era.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: The second part reviews the literature and proposes theoretical hypotheses. The third part is an introduction to our data sources, variable definitions, descriptive statistics, and research methods. The fourth part analyzes the impact of internet use on the entrepreneurial decision-making and entrepreneurial scale of returned migrant workers and further analyzes the regional heterogeneity and heterogeneity of entrepreneurial types of impact. The fifth part discusses the impact mechanism of internet use on the entrepreneurial decision-making and scale of returned migrant workers. The sixth part presents the conclusions and policy implications.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Analysis

2.1. A Literature Review of the Influencing Factors of Returned Migrant Workers’ Entrepreneurship

This paper attempts to explore the impact of internet use on the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers. First, we need to understand what factors affect the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers, and does the literature cover the factors inherent to the internet? Existing research believes that the factors affecting the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers are multidimensional, including both macro factors and micro factors. At the macro level, scholars have studied the impact of the economic environment, legal system, policy support and other factors on the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers. The regional economic developmental environment can influence entrepreneurial activities through regional institutional factors, human factors, financial factors, and technical factors [12], resulting in differences in the entrepreneurial direction, form and scale of returned migrant workers across different regions of China [13]. Regarding the legal system, Baumol (1990) proposed that the level of the regional rule of law and the degree of marketization affect the direction of entrepreneurship [14]. Data from 2005–2015 of 70 countries show that there are stronger positive effects of an improved regulatory environment and government size on the quantity of entrepreneurship in developing countries than in developed countries [15]. In recent years, the policy and institutional innovations of China’s central and local governments that favor rural areas have created new opportunities for agricultural and rural development, attracting migrant workers to “return” to the countryside [16,17], such as financial, industrial, and land policies, has accelerated the pace of returned migrant workers’ entrepreneurship.

Howard (1989) defines entrepreneurship as the behavioral process of integrating resources to develop opportunities [18]. From a micro perspective, entrepreneurship is the result of the personal endowment and resource integration of returned migrant workers. The resource endowment of entrepreneurs mainly comes from three dimensions: resource capital (economic capital), human capital, and social capital [19]. Evans and Boyan (1989) argue that initial economic capital is one of the two key factors influencing entrepreneurial behavior [20]. Economic capital affects the opportunity development process, and those returned migrant workers with higher economic capital have more entrepreneurial motivation and are more likely to identify entrepreneurial opportunities. The identification of entrepreneurial opportunities is based on the premise of collecting and processing entrepreneurial information sources, while discovering and effectively identifying entrepreneurial information sources is based on economic capital [21]. Human capital is the sum of physical strength, knowledge, technology, ability, etc., that represent the economic value condensed in workers [22], and education training and experience accumulation are two important sources of human capital formation [23]. Good human capital can improve the quality of entrepreneurs’ decision-making and information recognition and enhance their possibility of achieving entrepreneurial success. At the same time, returning to one’s hometown to start a business is closely related to the experience of going out to work. The experience of going out to work can enhance the accumulation of human capital for returned migrant workers, expand their access to information, and train them in the technology, management experience and entrepreneurship required for entrepreneurial activities, all of which have a very beneficial positive impact on the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers [24,25,26]. Social networks are the main source of entrepreneurial opportunities for returned migrant workers, and personal social capital significantly affects the discovery, judgment and utilization of entrepreneurial opportunities. Shane and Venkataraman (2000) proposed that since the development of personal social networks can enhance entrepreneurs’ confidence and ability to resist entrepreneurial risks, whether entrepreneurs develop discovered entrepreneurial opportunities is influenced by the degree of network support [27] that they have access to. Peng and Du et al. (2018) also show that for returned migrant workers, social capital is not only related to whether and what kind of entrepreneurial opportunities can be found but also affects the performance of entrepreneurship [28].

2.2. Theoretical Hypothesis Regarding the Way That Internet Use Affects the Entrepreneurial Decision-Making of Returned Migrant Workers

With the advent of the internet era and the rise of rural entrepreneurship, many studies have been conducted in the academic community to examine the relationship between internet use and the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers. Entrepreneurial decision-making entails the process of receiving, interpreting, and processing information, which is influenced by individuals and circumstances [29]. The use of information technology products such as the internet can broaden the channels enabling internet users to acquire knowledge, skills or experience, enhancing the human capital level, and improving the productivity of users and other factors of production [30,31], thereby facilitating the entrepreneurial decisions of returned migrant workers who use the internet. Entrepreneurial decision-making depends not only on the skills and abilities of individuals but also on the availability of support from social networks [32], and the information communication and financing functions of social networks can be leveraged to reduce the cost of entrepreneurship and increase the probability of starting a business [33,34,35]. The use of the internet can affect the social networks of returned migrant workers in two ways. First, it provides communication opportunities, increases weak social networks, and helps returned migrant workers obtain entrepreneurial information and financial support from friends and relatives. Second, such use helps maintain existing close relationships and develop a strong social network, that is, it helps returned migrant workers maintain and develop good and broad social relationships [36]. Barnett et al. (2019) also show that internet use exerts a positive impact on farmer entrepreneurship, with social networks and access to information playing a mediating role in the impact of internet use on farmer’s entrepreneurship [37]. In addition, internet-derived applications also exert a significant impact on the entrepreneurial decision-making of returned migrant workers. For example, e-commerce is a business and economic activity based on internet infrastructure, and it carries the advantages of reducing service costs, improving the quality of goods and services, and expanding access to information [38]. The development of e-commerce has also brought online payment services, financial services and training services to farmers, which helps to facilitate them breaking through the restrictions of business incubation [39]. Accordingly, this paper proposes Hypothesis H1:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Internet use has a positive impact on the entrepreneurial decision-making of returned migrant workers.

2.3. Theoretical Hypothesis of Internet Use Affecting the Scale of Entrepreneurship among Returned Migrant Workers

Since the entrepreneurial field is mainly concentrated in labor-intensive industries such as manufacturing and construction [40], the expansion of venture capital investment and the number of enterprises started by returned migrant workers are conducive to fully leveraging the important role of small and medium-sized enterprises in promoting employment and poverty reduction [41,42], driving the diffusion of technology and the application of new products and equipment, and stimulating greater vitality in rural economic growth. Whether regarding a larger investment scale or a greater number of enterprises, such expansion necessitates higher requirements for entrepreneurs’ capital, technological innovation ability and operation and management capacity. Financial constraints are considered to be an important factor affecting the scale of entrepreneurship [43], and the willingness of financial institutions to provide financing directly affects the conduct of entrepreneurial activity [44,45]. The use of communication technologies such as the internet can improve the level and scale of farmers’ access to credit by reducing financial institutions transaction costs and improving the information symmetry between credit supply and demand [46,47,48], effectively meeting the funding needs of returned migrant workers in starting their own businesses. At the same time, the application of new technologies such as the internet can significantly reduce the cost of information exchange and the coordination of internal and external communication in enterprises, promote the intelligence of enterprise business decision-making data, and improve the efficiency of technological innovation [49], thereby improving the technological innovation and management capabilities of returned migrant workers. In addition, for the most critical production and sales stages of entrepreneurial activities, internet procurement can save time and labor costs and has significant advantages in terms of the diversification of choices and the comparability of products. Internet sales can reduce the distribution level, simplify the process of corporate services and promotions, and reduce the transaction costs of enterprises [50], affecting the investment scale and willingness of returned migrant workers to start a business. Accordingly, this paper proposes Hypothesis H2:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Internet use has a positive impact on the scale of entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data Source

Since entrepreneurship is generally based on collective decision-making and joint participation by the family and venture capital and profits are difficult to subdivide by individual family members, this paper applies household-level data to study the impact of internet use on the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers. The microdata used in this paper come from the CFPS database, which contains the relevant indicator variables for the internet and the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers required for research that can meet the needs of analyzing internet use and returned migrant workers’ entrepreneurship. The CFPS cover 25 provinces in China and more than 40,000 people using data from a baseline survey in 2010 that has been conducted every two years since then. This paper uses data from five rounds of national surveys from the period between 2010 and 2018. This paper cleans the data as follows: (1) Since the research object of this article is returned migrant workers, samples with either current rural household registration or urban household registration but that held previous rural household registration were selected; (2) Rural households were identified. The attributes of currently living or working in a rural area and having work experience outside of that area are two major characteristics of returned migrant workers. Therefore, according to the CFPS questionnaire rules, this paper defines that portion of rural residents with a workplace near their place of residence as rural households. (3) The 5 rounds of data were matched and migrant workers who have worked outside of their hometown, that is, migrant workers who have returned to their hometowns, were screened out. A sample of 1096 returned migrant workers was finally obtained. (4) To control the influence of outliers, variables such as the continuous variable venture capital scale and per capita household income were shrunk at the 1% level, and logarithmic treatment was applied.

3.2. Variable Definition and Measurement

The explained variables used in this paper are entrepreneurial decision and entrepreneurial scale. Based on the responses to the CFPS question “Whether the family members engage in self-employed business”, the dependent variable “entrepreneurial decision-making” is constructed. If the answer is yes, then the variable takes a value of one; otherwise, it takes a value of zero. The scale of entrepreneurship is divided into two further variables: the scale of entrepreneurial investment and the number of start-up enterprises. Among these, the scale of venture capital is measured by the logarithmic value of total entrepreneurial investment, and the number of start-up enterprises is measured by the number of projects in which family members engage in self-employment or private enterprises. Most of the literature focuses on entrepreneurial choice, that is, on the question of whether returned migrant workers make entrepreneurial decisions. This article uses both entrepreneurial decision-making and entrepreneurial scale as outcome variables, which can more accurately reflect the entrepreneurial behavior of returned migrant workers.

The explanatory variables in this paper are for internet use. Based on these two CFPS questions, “do you use mobile devices to access the internet?” and “do you use computers to access the internet,” the independent variable “Internet use” is defined. If the response to one or both of the two questions is “yes,” then internet use is confirmed, and the variable takes a value of one; otherwise, it takes a value of zero.

In terms of control variables, this paper is maintain consistency with the literature by covering both the household and individual levels. Household-level control variables include household income per capita, family size, and cash deposit balance, and individual-level control variables include the age, education level, marital status, health level, unemployment insurance, sex and political status of returned migrant workers.

Table 1 lists the descriptive statistical results for each of the variables. In this paper, a focus is maintained on the explained variables: entrepreneurial decision-making, the scale of entrepreneurial investment, the number of start-ups, and the core explanatory variable, namely, internet use. Among them, the average value of entrepreneurial decision-making variables is 0.171, indicating that the proportion of returned migrant workers who started businesses was 17.1%, which is much higher than the rural entrepreneurship rate of 7.7% and is consistent with the reality that returned migrant workers are the main force behind rural entrepreneurship. The mean logarithmic value of entrepreneurial investment was 0.315, the standard deviation was 0.868, and the extreme value of this variable was also very large, indicating that the scale of entrepreneurial investment of returned migrant workers was quite distinct. The average number of start-up enterprises was 0.182, indicating that most migrant workers who returned to their hometowns to start businesses only engaged in a single entrepreneurial project. In terms of internet use, the proportion of migrant workers returning to their hometowns who use the internet is approximately 57.8%, which is much higher than the 38.4% average internet penetration rate in rural areas in China during the same period but still lower than the 75% average internet penetration rate in urban areas in China, indicating that the internet use in the rural areas of China needs to be improved. The descriptive results of the control and mediation variables are not elaborated on.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the variables.

To visually observe the relationship between internet use and the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers, this paper divides the sample into two groups, one for returned migrant workers who use the internet and the other for returned migrant workers who do not use the internet. The mean difference test between the two groups was performed to compare the internet user group and the nonuse group for significant differences, and the test results are shown in Table 2. The entrepreneurship rate of returned migrant workers who use the internet was 21.6%, and the entrepreneurial rate of returned migrant workers who do not use the internet was 11%. The difference between the two was 10.6%, and this difference was significant at the 1% level. Similarly, the scale of entrepreneurship investment and the number of businesses started by returned migrant workers who use the internet are significantly higher than that of those who do not use the internet at the 1% level.

Table 2.

Test of the mean difference between groups.

3.3. Research Models

In this paper, probit and OLS models are constructed to study the impact of internet use on entrepreneurial behavior in two dimensions. First, to study the impact of internet use on the entrepreneurial decision-making of returned migrant workers, this paper constructs a probit model. The expressions for latent variables and probit model are shown in Equations (1) and (2), respectively:

where yi is entrepreneurial decision-making; interneti is internet use; Xi is a series of control variables; and δi is the provincial fixed effect. α is the parameter of interest in this paper, which captures the causal effect of internet use on the entrepreneurial decision-making of returned migrant workers.

Second, to study the impact of internet use on entrepreneurial scale, this article constructs an OLS estimation regression model, as shown in Equation (3).

where yi represents the two explained variables, namely, the scale of entrepreneurship investment and the number of start-up enterprises; interneti refers to the use of the internet; Xi is a series of control variables; and δi is the fixed effect of the province. α is the causal effect of internet use on the scale of entrepreneurship among returned migrant workers.

4. Results

4.1. Results of the Benchmark Regression Model

This article divides entrepreneurial behavior into two dimensions: entrepreneurial decision-making and entrepreneurial scale. The following two subsections report the benchmark regression results of internet use on the entrepreneurial decision-making and entrepreneurial scale of returned migrant workers.

4.1.1. Benchmark Regression of Internet Use and Entrepreneurship Decision-Making

The probit model is used in this paper to estimate the impact of internet use on the entrepreneurial decisions of returned migrant workers. The regression results are shown in Table 3. All columns have been included in the provincial fixed effects, and the standard error is robust.

Table 3.

Benchmark regression results of internet use for entrepreneurial decision-making.

Column (1) in Table 3 includes only the core explanatory variables. The use of the internet positively affects the entrepreneurial decision-making of returned migrant workers at the 1% level. Furthermore, Columns (2) and (3) introduce control variables, and the results show that the use of the internet still significantly promotes the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers. From Column (3), it can be seen that the marginal effect of using the internet on entrepreneurial decision-making is 0.06; that is, the use of the internet increases the entrepreneurial rate of returned migrant workers by 6%, and it is significant at the 5% level. The use of the internet significantly contributes to entrepreneurial decision-making.

The estimation results of the control variables are basically consistent with the literature. Regarding the household variable, per capita household income significantly positively affects entrepreneurial decisions at the 1% level, i.e., economic capital plays a significant role in whether households make entrepreneurial decisions. Because entrepreneurship requires initial investment funds and the payback period is longer, the greater the family income that there is, the stronger the ability to economically resist entrepreneurial risks, and therefore the stronger the willingness to start a business. The coefficients for total cash and deposits are also positive, so savings can provide some protection for the early stage of entrepreneurial activities. In addition, returned migrant workers with larger families are more likely to make entrepreneurial decisions; specifically, for each single increase in the number of family members, the entrepreneurial rate of returned migrant workers significantly increases by 3%.

Concerning the control variables at the individual level of returned migrant workers, the impact of education on entrepreneurship shows a significant U-shaped feature of first declining and then rising, and a turning point occurs when the highest education is junior high school. This may be because when the education of returned migrant workers is below the inflection point, returned migrant workers with higher education levels are more likely to find suitable jobs locally, but returned migrant workers with lower education levels have difficulty meeting the educational requirements of local employers, forcing them onto the road of independent entrepreneurship. When the level of education is higher than the threshold, the higher level of education indicates that returned migrant workers can meet the requirements of human capital accumulation for entrepreneurship in the new era, and their willingness to start a business is stronger. Unemployment insurance significantly negatively affects entrepreneurial decision-making and has an obvious shackling effect on entrepreneurial behavior. Returned migrant workers’ marriage, maleness, health level, and party membership also had positive marginal effects on their entrepreneurial decision-making, but these effects did not pass the significance test. Age had no significant impact on the entrepreneurial decision-making of returned migrant workers.

4.1.2. Benchmark Regression of Internet Use on the Entrepreneurial Scale

Table 4 reports the impact of internet use by returned migrant workers on the scale of entrepreneurship. All equations incorporate the province fixed effect and use the robust standard error.

Table 4.

Benchmark Regression Results of Internet Use on Entrepreneurship Scale.

Columns (1) and (2) in Table 4 show the impact of internet use on the scale of entrepreneurial investment for returned migrant workers. Internet use significantly positively affects the scale of entrepreneurial investment of returned migrant workers at the 1% level. Compared with those returned migrant workers who do not use the internet, the scale of entrepreneurial investment of those returned migrant workers who do increased by 18% (e0.169 − 1 ≈ 0.18). Columns (3) and (4) show the impact of internet use on the number of businesses started by returned migrant families. The use of the internet significantly positively affects the number of businesses started at the 5% level. Returned migrant workers who use the internet set up an average of 0.07 more enterprises than those who do not use the internet, accounting for 36% of the average number of projects (0.065/0.182 ≈ 0.36). On the whole, the use of the internet can significantly increase the scale of entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers.

In terms of control variables, per capita household income and total cash deposits positively affect the scale of entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers. Households with more per capita income and savings have more economic endowments and can provide better financial support for returned migrant workers to venture out and start businesses. The estimated coefficient of family size is also significantly positive because the social network in rural areas is based on kinship and bloodline, and family members comprise the most closely related form of social capital. The more family members that there are, the more financial, information, and human capital support returned migrant workers receive with which to invest and start businesses. The impact of the educational experience of returned migrant workers on the scale of entrepreneurship showed a significant U-shaped characteristic of first declining and then rising, and this threshold also occurred when the level of education was junior high school. Unemployment insurance significantly negatively affects the scale of entrepreneurship, and the shackling effect is still obvious. The estimated coefficients for other variables failed the significance test.

4.2. Endogenous Treatment

There are many factors that simultaneously affect the internet use and entrepreneurial behavior of returned migrant workers; for example, economic capital provides the economic conditions for returned migrant workers to use the internet, but it can also reduce entrepreneurial risks and promote entrepreneurial behavior. Twelve control variables have been included in this study, but there is still a possibility of missing variables. In addition, some families may have internet use needs and form usage behaviors that facilitate entrepreneurial activities; that is, the model may have reverse causality issues. Survey data of internet usage may also contain measurement errors. Therefore, this paper uses the instrument variable method (IV) to address endogeneity.

Referring to the practice of Zhou and Hua (2017) [51], the IV selected in this paper is the average network usage of the villages (communities) where the returned migrant workers are located, and this meets the IV conditions. First, the average network usage of the villages (communities) where the returned migrant workers are located reflects the network accessibility and network penetration of the area and is correlated with the probability of households using the internet in the area. Second, the regional use of the internet has a strong exogenous effect on the entrepreneurial behavior of returned migrant workers.

Table 5 reports the estimation results of the regression of instrumental variables. According to the estimation results of the first stage, the F value is greater than the empirical value of 10, which indicates that the regional average network usage level significantly increases the probability of returned migrant workers using the internet. These estimates speak to economic significance, and it can be concluded that the selected IV is not a weak instrumental variable. The results of the second phase show that after correcting for possible endogeneity problems, the coefficient of internet use is still positive, and all variables have passed the significance test. Overall, the conclusions of this paper can be considered robust.

Table 5.

Impact of Internet Use on Entrepreneurship of Returned Migrant Workers: Instrumental Variable Method.

4.3. Robustness Test

4.3.1. Replacing the Explanatory Variable Measures

Above, we have focused on the impact of internet use on the entrepreneurship of re turned migrant workers, but the intensity of internet use may also have an impact on the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers. This paper uses the weekly internet usage pattern of returned migrant workers to proxy internet usage intensity and then explores the impact of internet usage intensity on entrepreneurship. The regression results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Test Results of Robustness of Internet Usage Intensity.

As shown in Table 6, the intensity of internet use positively affects entrepreneurial decision-making, the scale of entrepreneurial investment and the number of enterprises started by returned migrant workers at a significance level of 1%. Overall, the intensity of internet usage significantly promotes the choice of entrepreneurship and the investment scale of returned migrant workers.

4.3.2. Replacement of the Regression Model

Considering that entrepreneurial decision-making is a dummy variable, probit estimation had been applied. In this section, the OLS model was used, and the regression results are shown in Column (1) in Table 7. Internet use still significantly positively influences the entrepreneurial decisions of returned migrant workers. In addition, considering that the number of returned migrant workers’ enterprises is a nonnegative integer, this paper uses Poisson regression to re-estimate the impact of internet use on the number of returned migrant workers’ enterprises. From Column (2), we can see that the marginal effect of internet use on the number of businesses started is 0.073, which is significant at the 5% level. This value is very close to the 0.065 in the benchmark regression. In summary, the conclusion remains robust after changing the regression model.

Table 7.

Robustness Test Results of the Replacement Regression Model.

4.4. Analysis of Heterogeneity

4.4.1. Regional Difference Analysis

Based on the geographical location of the provinces in the sample, combined with the economic position of each province in China, this paper divides the sample into returned migrant workers in the eastern region and returned migrant workers in the central and western regions. Among them, the eastern region of China has a developed economy and a relatively complete infrastructure, including the internet, and Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong and other provinces and cities are all part of the eastern region. The level of economic development in the central and western regions lags behind, and the provisioning of infrastructure such as the internet is also more backward. Table 8 shows the regression results of the subregion.

Table 8.

Impact of Internet Use on the Entrepreneurship of Returned Migrant Workers: Regional Grouping Results.

For the eastern region, the use of the internet has a positive marginal effect on the entrepreneurial decision-making and the investment scale of returned migrant workers and a negative marginal effect on the number of start-ups, but none of these effects pass the significance test. However, for the central and western samples, the impact of internet use on entrepreneurial decision-making, investment scale, and number of start-ups was significant at the 1% level, and the regression coefficient was generally larger. The speed of internet penetration in China is asymmetric, and the internet was introduced earlier in the eastern region, and its popularity grew faster than that in the central and western regions. This has released a significant portion of the driving effect of internet use on entrepreneurship in the eastern region, so the promotion effect of internet use on returned migrant workers’ entrepreneurship in the eastern region is not as strong as that in the other regions.

4.4.2. Impact of Internet Use on Different Types of Entrepreneurship

According to the definition of Xavier-Oliveira et al. (2015) [52], entrepreneurial activities can be divided into “necessity entrepreneurship” and “opportunity entrepreneurship”. The former refers to self-employment to meet the basic needs of survival, which is also sometimes known as “survival entrepreneurship”. It is characterized by targeting and capturing the opportunities in existing markets, and these entrepreneurs generally work in industries with low technical barriers, low risk, low profits and low requirements for highly developed skills. The latter refers to entrepreneurial activities that are aimed at seizing business opportunities. Opportunity entrepreneurship can obtain more financial lending support, which can not only solve the employment problem of the farmers themselves but also gives rise to certain employment opportunities that are generally more skilled and more economically beneficial [53].

The CFPS database does not distinguish the purposes of households’ entrepreneurship. According to whether workers are employed in the entrepreneurial activities of returned migrant workers, entrepreneurship is categorized in this study into opportunity entrepreneurship and necessity entrepreneurship. Because hiring workers requires a payment in labor remuneration, the motivation for returned migrant workers to start businesses is likely driven by more than just survival needs. If workers are hired to start a business, it can be regarded as an opportunity entrepreneurship; otherwise, it is a necessity entrepreneurship. Table 9 reports on the impact of internet use on necessity entrepreneurship and opportunity entrepreneurship.

Table 9.

Regression Results of internet Use on Different Types of Entrepreneurship.

The marginal effect of internet use on necessity entrepreneurship is 0.055; that is, compared with returned migrant workers who do not use the internet, the necessity entrepreneurship rate of returned migrant workers who do use the internet increases by 5.5%. At the same time, it is found that the use of the internet does not play a significant role in promoting opportunity entrepreneurship, which may be because opportunity entrepreneurship requires stronger entrepreneurial ability, more funds, and the ability to surmount higher technical and industry barriers, and even returned migrant workers do not have such strength, so their entrepreneurship is mainly focused on necessity entrepreneurial activities. In summary, the influence of internet use in promoting the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers mainly pertains to necessity entrepreneurship.

5. Discussion

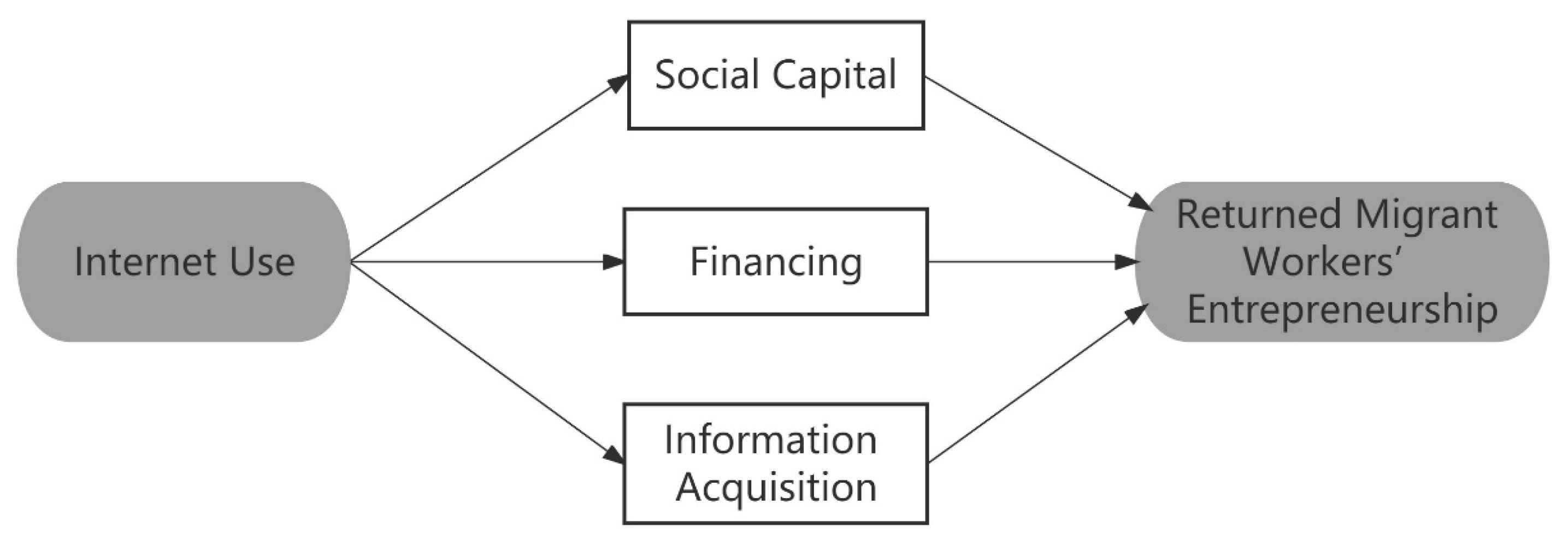

This paper empirically analyzes the impact of internet use on the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers. The results show that internet use can positively affect the entrepreneurial decisions and the entrepreneurial scale of returned migrant workers. This is consistent with the findings of Fan et al. (2022) [10], Huang et al. (2022) [11] and Yuan and Shi (2019) [54]. Therefore, the question arises as to what the impact mechanism of internet use on the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers is. According to the literature review, there may be three indirect mechanisms of internet use on the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers, namely, the social capital effect, financing effect and information acquisition effect of internet use (Figure 2). This section further discusses the channels through which internet use affects household entrepreneurship and the significance of these channels.

Figure 2.

The impact mechanism of internet use on the entrepreneurship.

5.1. The Mediating Effect of Social Capital

As the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition [55], social capital plays an important role in the entrepreneurial activities of returned migrant workers. On the one hand, potential entrepreneurs can obtain information on entrepreneurial matters by talking to experienced relatives and friends. On the other hand, in those communities with higher entrepreneurial engagement, people who socialize more frequently are more likely to engage in entrepreneurial activities because such sociable people are more heavily influenced by their peers. The use of the internet consolidates existing social networks while expanding new networks at lower cost, thus increasing the social capital of families. Banquets are a unique way of socializing in Chinese culture, and this opportunity can be used to negotiate and expand social capital. Therefore, this paper takes expenditure on eating out as a proxy variable to measure social capital and analyzes its mediating effect.

In Table 10, Column (1) displays the regression results of internet use on the dining out behavior of returned migrant workers. The results show that internet use significantly positively affects the expenditure of eating out at the 1% level, and when returned migrant workers use the internet, the expenditure of eating out increases by 57.7%, indicating that internet use can enhance social capital. Columns (2)~(4) report the regression results of both internet use and eating out on entrepreneurial decision-making and entrepreneurial scale. Internet use still significantly positively affects family entrepreneurial decision-making and scale. The above results prove that internet use can promote entrepreneurship by increasing the social capital of returned migrant workers, whether it is for making entrepreneurial decisions or expanding the scale of entrepreneurship, and social capital exerts a mediating effect. This is consistent with the findings of Liu et al. (2022) [56], Zhou and Fan (2018) [57] and Ma (2002) [25].

Table 10.

The Mediating Effect of Social Capital.

5.2. The Mediating Effect of Financing

Entrepreneurs are generally constrained by funds, and this is a problem that is more pronounced in regions where financial markets are less than optimal. The use of the internet has brought returned migrant workers closer to financial market. New financing and payment methods such as internet finance and mobile payment based on the internet have facilitated the financing of farmers, effectively reducing the financing costs and eased the financing constraints of returned entrepreneurs. In rural China, informal financing from relatives and friends is just as important as formal financing from banks and financial institutions. In this paper, bank loans and loans among relatives and friends are used as proxy variables to measure the levels of formal financing and informal financing, and the mediation effect of financing is analyzed (In CFPS, the questions about the above two variables are: “Excluding mortgage loan, does your family have other unpaid-off bank loan?”, “Excluding house purchase, construction, and decoration, is your family still in debt to individuals and institutions (e.g. private loan institution, relatives, friends) other than the bank for other purposes?” If the respondent’s answer is yes, the variable is set to 1, otherwise it is set to 0.). The Column (1) shown in Table 11 and Table 12 reports the regression results of internet use on bank loans and loans among relatives and friends, respectively. The results showed that the positive effect of internet use on bank loans and loans among relatives and friends was not significant. Therefore, there is no mediating effect of internet use on promoting financing.

Table 11.

Mediating Effect of Formal Financing.

Table 12.

Mediating Effect of Informal Financing.

5.3. The Mediating Effect of Information Acquisition

Information plays an important role in entrepreneurial activities. The capture of entrepreneurial opportunities, the daily operational management of enterprises and the expansion of sales channels are inseparable from the support of information [58,59]. This paper refers to the practice of Liu et al. (2022) [56], uses online business as a proxy variable to measure information acquisition, and analyzes the mediating effect of information acquisition (In CFPS, the questions about this variable are “The frequency of using the internet to do commercial related activities.” If the response is almost every day, then the value is assigned to 1, and it is assigned to 0 otherwise.).

In Table 13, Column (1) reports the regression results of internet use to online business. The results show that internet use significantly positively affects the frequency of commercial information obtained by returned migrant workers. Columns (2)~(4) report the regression results of internet use and online business on the entrepreneurial decision-making and entrepreneurial scale of returned migrant workers. Internet use still significantly positively affects household entrepreneurial decision-making and entrepreneurial scale, and compared with the benchmark regression results, both the marginal effect of internet use, and the significance level are reduced, which means that the internet has an information acquisition effect in promoting the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers. This is consistent with the findings of Zhou and Hua (2017) [51].

Table 13.

The Mediating Effect of Information Acquisition.

6. Conclusions

Using data from five rounds of surveys from the CFPS covering the period from 2010 to 2018, this paper empirically examines the impact of internet use on the entrepreneurial decision-making and entrepreneurial scale of returned migrant workers at the micro level. The results show the following: (1) Compared with those returned migrant workers who do not use the internet, those who do not only increase their probability of starting a business by 6% but also increase the probable scale of investment by 18% and the probable number of enterprises founded by 36%. The use of the internet not only stimulates the enthusiasm of returned migrant workers to start their own businesses but also significantly impacts the scale of entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers. This is crucial for countries with limited job opportunities in rural areas that rely on entrepreneurship to create employment. (2) The role of internet use in promoting the entrepreneurship of returned migrant workers is heterogeneous across regions. For developed regions or countries, where the introduction of the internet happened earlier and has a higher penetration rate, the role of internet use in promoting entrepreneurship has already been realized to a significant extent. Currently, the impact of internet use on promoting entrepreneurship may not be as pronounced. However, for relatively underdeveloped countries and regions, the effect of internet use in fostering entrepreneurship is particularly prominent. (3) The use of the internet promotes entrepreneurship by increasing the social capital and information access of returned migrant workers, but the use of the internet does not play a role in promoting financing for returned migrant workers’ entrepreneurship. (4) The internet use rate of returned migrant workers is 57.8%, which is higher than the average 38.4% level of internet penetration in rural China (as of 2019, the global rural internet penetration rate was 38%). However, it is still lower than the average 75% level of internet penetration in urban areas of China (as of 2019, the global urban internet penetration rate was 72%). Whether in China or globally, the urban-rural disparity in internet penetration rates is widespread. There is a need to enhance global efforts in promoting internet access in rural areas and increasing the penetration of internet usage among rural households.

Based on the results of this study, the following suggestions are made: (1) Internet use can significantly promote entrepreneurship and expand the scale of entrepreneurial activities among returned migrant workers. However, according to data from the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), only 38% of households in rural areas worldwide had access to home internet in 2019, which hinders the effective utilization of internet use in promoting entrepreneurship. In light of this, it is recommended that governments of various countries strengthen the construction of internet infrastructure in rural areas. This includes promoting the extension of mobile communication networks, fiber-optic broadband, and other information technologies to rural areas, improving the coverage of rural internet infrastructure, and leveraging the power of the internet to better facilitate rural entrepreneurship. (2) Internet use is an interactive process of internet infrastructure popularization and personal initiative. It is crucial to enhance the information literacy of users in order to fully leverage the entrepreneurial benefits of internet use. However, existing research [60,61] widely indicates that farmers in developing countries such as China and India, including returned migrant workers who are also farmers, have lower levels of information literacy and weaker internet usage capabilities. In this regard, it is recommended that the government conduct full-coverage and multilevel information education and training activities for returned migrant workers, enhance their ability to obtain information and identify online opportunities, and focus on improving their internet application level in such fields as e-commerce, digital management and intelligent production. (3) The proportion of returned migrant workers who start businesses, the scale of entrepreneurial investment and the number of enterprises started are much higher than those of ordinary farmers. To improve the level of rural entrepreneurship, it is necessary to give full play to the role of returned migrant workers as the main force behind entrepreneurship. However, on a global scale, there are not many farmers who leave rural areas and then return to rural areas again. Moreover, the proportion of farmers who engage in entrepreneurship upon returning to their hometowns is even smaller. This is associated with the lower level of public services and limited support for rural entrepreneurship in rural areas. Therefore, focusing on improving the level of public services for entrepreneurship in rural areas is recommended, as well as focusing on solving the problem of funding for returned migrant workers seeking to start their own businesses, strengthening the level of fiscal and tax exemption support, and attracting migrant workers who are more knowledgeable about technology and management to return to their hometowns to start businesses.

This study has two limitations. First, the CFPS have been conducted every two years since 2010. The questionnaire cannot directly identify respondents as returned migrant workers. In this study, it is proposed that if respondents reported being engaged in “off-farm employment” at least once during the first four interviews, they would be considered as having experience in rural migrant work and identified as returned migrant workers. However, it should be noted that this method may introduce bias. According to calculations, respondents in the “off-farm employment” category spend 70% of their time in that status during the surveyed year. However, there is still a possibility that some respondents who were not engaged in off-farm employment during the interview period may have been involved in such activities at other times, leading to sample omissions and errors. Second, there are various types of enterprises that are founded by returned migrant workers, including agricultural product planting enterprises, tourism enterprises, processing and manufacturing enterprises, etc. It is evident that the impact of internet use on entrepreneurial decision-making and entrepreneurial scale varies across these different types of enterprises. Currently, due to data limitations, this study can only provide an overall analysis of the influence of internet use on the entrepreneurial decision-making and entrepreneurial scale of returned migrant workers. This represents a major limitation of this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X. and Y.S.; methodology, M.K.; software, Y.X. and Q.W.; data curation, J.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.X. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, Y.X. and R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 310422102), Postdoctoral Research Foundation of China (Grant No. 212400202).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ali, A.; Yousuf, S. Social Capital and Entrepreneurial Intention: Empirical Evidence from Rural Community of Pakistan. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naminse, E.Y.; Zhuang, J.; Zhu, F. The relation between entrepreneurship and rural poverty alleviation in China. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 2593–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, B.; Melo, I.C. Fostering innovative SMEs in a developing country: The ALI program experience. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, S.; Ahlstrom, D.; Wei, J.; Cullen, J. Business, Entrepreneurship and Innovation toward Poverty Reduction. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2020, 32, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Yang, C.; Yan, S.C.; Wang, W.K.; Xue, Y.J. Alleviating Relative Poverty in Rural China through a Diffusion Schema of Returning Farmer Entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Yu, B.; Ma, J. Research on the Impact of Digital Empowerment on China’s Human Capital Accumulation and Human Capital Gap between Urban and Rural Areas. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Chen, J.; Li, J. Rural Innovation System: Revitalize the Countryside for a Sustainable Development. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 93, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.P.; Liu, X.H.; Wang, C.R. The influence of internet finance on the sustainable development of the financial ecosystem in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital Economy, Financial Inclusion and Inclusive Growth—ProQuest. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/abbe647cd549b27f2a5822b17821e497/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=1806366 (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Fan, H.M.; Zhang, N.; Meng, C.Y. Internet use, finance acquisition and returning migrant workers’ home entrepreneurship—Empirical analysis based on CLDS2016. Singap. Econ. Rev. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.J.; Huang, Y.; Huang, R.Y.; Xie, G.J.; Cai, W.W. Factors influencing returning migrants’ entrepreneurship intentions for rural e-commerce: An empirical investigation in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Economic Development, Endowments and the Regional Variation of Entrepreneurship. J. Harbin Univ. Commer. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 2, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. Research on the Development Level of Rural E-Commerce in China Based on Analytic Hierarchy and Systematic Clustering Method. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, W.J. Entrepreneurship—Productive, unproductive, and destructive. J. Polit. Econ. 1990, 98, 893–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, F.; Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M. Institutions and Entrepreneurship Quality. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 51–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fan, Y. Research on the linkage mechanism between migrant workers returning home to start businesses and rural industry revitalization based on the Combination Prediction and Dynamic Simulation Model. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 1848822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Zhu, H. Return Migrants’ Entrepreneurial Decisions in Rural China. Asian Popul. Stud. 2020, 16, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, H.S. New Business Ventures and the Entrepreneur; Irwin: Martinsville, OH, USA, 1989; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Firkin, P. Entrepreneurial capital: A Resource—Based Conceptualization of the Entrepreneurial Process. Available online: http://Imd.massey.ac.nz/documents/WorkingPaperNo7.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Evans, D.S.; Boyan, J. An estimated model of entrepreneurial choice under liquidity constraints. J. Polit. Econ. 1989, 97, 808–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Dai, Y.; Xie, W. The Impact of the Entrepreneurial Resource Endowment of the New Generation of Migrant Workers on Entrepreneurial Opportunities. Guangdong Agric. Sci. 2014, 41, 220–225. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, T.W. Investment in human capital. Am. Econ. Rev. 1961, 51, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, R. On the mechanics of economic development. J. Monet. Econ. 1988, 22, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, G.; Wang, M.; Zhang, B. Research on the Influence Mechanism of Dual Social Network Embeddedness Combined Ambidexterity on Entrepreneurial Performance of Returning Migrant Workers. Entrep. Res. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.D. Social-capital mobilization and income returns to entrepreneurship: The case of return migration in rural China. Environ. Plan. A 2002, 34, 1763–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, P. Improving the Entrepreneurial Ability of Rural Migrant Workers Returning Home in China: Study Based on 5675 Questionnaires. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Du, J. Social Capital, Resource Acquisition, and Return Migrant Peasants’ Entrepreneurial Performance: An Empirical Study Based on the Micro Survey Data from the Yangtze River Delta in China. Rev. Cercet. Interv. Soc. 2018, 61, 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- De Winnaar, K.; Scholtz, F. Entrepreneurial Decision-Making: New Conceptual Perspectives. Manag. Decis. 2019, 58, 1283–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, N.B.; Said Boustany, M.; Khater, M.; Haddad, C. Measuring the indirect effect of the Internet on the relationship between human capital and labor productivity. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2020, 34, 821–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, S. Internet use and rural residents’ income growth. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2020, 12, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramoullé, Y.; Kranton, R. Public goods in networks. J. Econ. Theory 2007, 135, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotte Kock, S.; Coviello, N. Entrepreneurship Research on Network Processes: A Review and Ways Forward. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, J.; Kousar, S.; Hameed, W.U. Antecedents of Sustainable Social Entrepreneurship Initiatives in Pakistan and Outcomes: Collaboration between Quadruple Helix Sectors. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Z. Network “Inter-embeddedness” and the Choice of Rural Family Entrepreneurship: A Further Discussion on Achieving Common Prosperity. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2022, 9, 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, W.A.; Hu, M.Z.; Wang, X. Does the utilization of information communication technology promote entrepreneurship: Evidence from rural China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2019, 141, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, N. Does e-commerce provide a sustained competitive advantage? An investigation of survival and sustainability in growth-oriented enterprises. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1411–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Li, B. A New Driver of Farmers’ Entrepreneurial Intention: Findings from e-Commerce Poverty Alleviation. WREMSD 2020, 16, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Geng, M. The Current Situation, Typical Models, and Countermeasures of Entrepreneurship among Returning Migrant Workers in Jiangsu Province under the Background of Rural Revitalization. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2022, 50, 222–225. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg, P. Micro, Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and the Global Economic Crisis: Impacts and Policy Responses; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; pp. 188–205. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, A. Explaining loan rate differentials between small and large companies: Evidence from Switzerland. Small Bus. Econ. 2012, 38, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, E.; Lusardi, A. Liquidity constraints, household wealth, and entrepreneurship. J. Polit. Econ. 2004, 112, 319–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Wang, T.; Zhao, X. Does Digital Inclusive Finance Promote Coastal Rural Entrepreneurship? J. Coast. Res. 2020, 103, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.W.; Khoury, T.A.; Hitt, M.A. The Influence of Formal and Informal Institutional Voids on Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2020, 44, 504–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siaw, A.; Jiang, Y.; Twumasi, M.A.; Agbenyo, W. The impact of internet use on income: The case of rural Ghana. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H. Digital Inclusive Finance, Multidimensional Education, and Farmers’ Entrepreneurial Behavior. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Z. Digital Empowerment: The Impact of Internet Usage on Farmers’ Credit and Its Heterogeneity. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2022, 324, 82–102. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Yang, S.; Chen, N. “Internet+”, Technological Heterogeneity and Innovation Efficiency-Research based on Panel Data of Provincial Industrial Enterprises. J. China Univ. Geosci. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 21, 125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Šaković Jovanović, J.; Vujadinović, R.; Mitreva, E.; Fragassa, C.; Vujović, A. The Relationship between E-Commerce and Firm Performance: The Mediating Role of Internet Sales Channels. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Hua, Y. Internet and Rural Family Entrepreneurship: An Empirical Analysis Based on CFPS Data. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2017, 5, 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Xavier-Oliveira, E.; Laplume, A.O.; Pathak, S. What motivates entrepreneurial entry under economic inequality? The role of human and financial capital. Hum. Relat. 2015, 68, 1183–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsrud, A.; Brännback, M. Entrepreneurial Motivations: What do we still need to know? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2011, 49, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Shi, Q. From Returning Home to Starting a Business: An Empirical Analysis of Impacts of the Internet Access on the Decision of Migrant Workers. South China J. Econ. 2019, 10, 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood: Westport, CT, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Ren, Y.; Mei, Y. How Does Internet Use Promote Farmer Entrepreneurship: Evidence from Rural China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Fan, G. Internet usage and household entrepreneurship: Evidence from CFPS. Econ. Rev. 2018, 5, 134–147. [Google Scholar]

- Aydiner, A.S.; Tatoglu, E.; Bayraktar, E.; Zaim, S. Information System Capabilities and Firm Performance: Opening the Black Box through Decision-Making Performance and Business-Process Performance. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 47, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahut, J.-M.; Iandoli, L.; Teulon, F. The Age of Digital Entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 56, 1159–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogesh, S.G.; Deenadayalu, S.R. Farmers’ Profitability through Online Sales of Organic Vegetables and Fruits during the COVID-19 Pandemic—An Empirical Study. Agronomy 2023, 5, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. Research in Cultivation of Farmer’s Information Literacy in Information Age. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Service Science, Technology and Engineering, Chongqing, China, 15–16 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).