Abstract

This article analyses how urban densification, primarily in relation to ecosystem services, is addressed in comprehensive plans from three cities in southernmost Sweden: Malmö, Lund and Helsingborg. The aim was to investigate and problematise how the comprehensive plans articulate and negotiate how to build dense cities while preserving and enhancing ecosystem services. A qualitative content analysis was performed on the comprehensive plans in use during the study period. The comprehensive plans were all ambitiously formulated. However, three recurrent issues were found. Planners struggled to address the issue of scale: Ecosystem services in the city were addressed when planning for densification, while ecosystem services for the city were either omitted or mentioned in the passing. The timeframe in relation to sustainable urban development was also not clarified. Most importantly, there were profound unclarities regarding priorities. Densification was suggested to provide all positive qualities simultaneously, including enhancing and supporting ecosystem services, which is, from a systems viewpoint, not possible. We suggest that when planning for sustainable cities, based on best available research, politicians should bring the prioritisation process to the fore, to clarify and address how to plan for dense, healthy cities with functioning ecosystem services in a more holistic manner.

1. Introduction

As urbanisation is the dominant demographic trend globally, finding solutions to urban sustainability challenges fall on urban planners, who have to accommodate ecology, equity and economy simultaneously [1,2]. Currently, the dominant planning strategy to combat the negative effects of urban growth is densification [3], which is thought to counteract urban sprawl, save valuable agricultural land, and decrease transportation and commuting. Ideally, dense cities should be sustainable in the strongest sense of the word, i.e., function within the ecological boundaries of the planet [2,4,5]. Ecosystem services, either in the city [6] or supporting the city from outside [7,8], are seen as pivotal for sustainable urban development. However, there are prevailing risks that densification not only competes with and undermines ecosystem services but also makes cities less healthy for human inhabitants, causing high levels of air pollution and traffic noise, lack of leaf-shade and too hot or cold microclimates. The challenge lies in how to plan for cities that are simultaneously ecologically sustainable, dense and healthy.

Swedish municipalities are legally obliged to clarify how they plan to use land and water resources; how the built environment should be used, developed and conserved; and how the municipality will secure national interests and comply with environmental quality regulations [9]. The comprehensive plan is the document in which planners attempt to negotiate conflicting goals [2,10,11]. In comprehensive plans, ecosystem services are often outlined as prerequisites for successful densification. The conundrum, from a sustainability perspective, is that there are conflicting goals between densification, on the one hand, and conserving and enhancing ecosystem services, on the other. Untangling the complexity of this goal conflict should contribute to better planning for sustainable urban development globally, as well as locally.

Several Scandinavian studies have demonstrated the complexity of securing sustainability factors while navigating conflicting goals in urban planning. Di Marino et al. [12], for example, found a number of conflicting values in Finnish comprehensive plans. Khoskar et al. [13] analysed the concept of ecosystem services in 231 Swedish comprehensive plans. Although the concept was generally adopted and explicit, the authors state that implementation needed further enhancement. Aagaard Hagemann et al., in an interview-based study, called for increased holistic thinking within Swedish municipalities, when planning for urban ecosystem services [6]. The concept of holism is relevant, as it points to the fact that urban planning is not merely about a political will to merge all good values but a conscious understanding of how changing one factor in a city may affect another. Berghauser Pont et al. [10] analysed 59 Swedish comprehensive plans and demonstrated that while densification has positive effects on public infrastructure, transport and economy, there were negative environmental, social and health impacts. Naess et al. [5], in a more theoretical article, critically discussed how urban densification is conceptually aligned with ecological modernisation, where de-coupling economic growth from environmental limitations makes it theoretically possible to combine densification with a lush environment. However, what is theoretically possible may not be viable because of both political and systemic factors. Sustainable urban development is challenging because of the many conflicting goals at play. These challenges need to be addressed by planners and given space in physical planning. There is a lack of research on how to explicitly and constructively handle inherent conflicts when formulating plans for simultaneously sustainable, dense and green cities. Analysing where goal conflicts occur or hide in comprehensive plans and what they lack in systemic understanding of sustainability, contributes to knowledge on how they can be avoided.

Hence, our primary aim with this study is to understand how the general goal of sustainable urban development, specifically related to densification and ecosystem services, is handled in the comprehensive plans of the three case municipalities Malmö, Lund and Helsingborg. The case municipalities were chosen as purposive samples, as they are the major cities in the densely populated region Scania. Our secondary aim, based on our results, is to point to major issues, which, if more explicitly addressed in comprehensive plans, in the long run may lead to planning for more sustainable cities where goal conflicts are consciously addressed. Our questions are the following: In what terms do the planners connect densification and ecosystem services to sustainable urban development in general? Where in the documents and how do they articulate how densification is to be utilised to create green, healthy cities? Finally, how do they, within the framework of comprehensive plans, negotiate discontinuities between densification, on the one hand, and ecosystem services, on the other?

The article is organised as follows: In Section 2, we present general political goals related to sustainable urban development, and how they are integrated into Swedish environmental law and planning. In Section 3, we present the research project as a whole, the choice to focus on comprehensive plans and how the qualitative content analysis was carried through. We also present our three case municipalities of Malmö, Lund and Helsingborg, their main planning challenges and how their comprehensive plans were and are currently organised. In Section 4, we present our qualitative content analysis of the comprehensive plans with regard to the findings big goals, scale, timeframe and priorities. In Section 5, we connect the findings to the general issues and obstacles related to sustainable urban development.

2. Background: Sustainable Development, Densification and Ecosystem Services in Swedish Municipal Planning

Already in 1999, Sweden adopted a generational goal, as well as a number of so-called national environmental objectives [14] through stage goals. In 2012, the Swedish government decided to add Ecosystem services to the environmental objectives, calling for the identification of services and integration of economic, political and other planning decisions [15]. In 2015, Sweden was a signatory to the SDGs and adopted the New Urban Agenda on housing and sustainable urban development in 2016, an action-oriented document to “drive sustainable urban development at the local level” [16]. A main challenge of the SDGs lies in the number of goals, their generic characteristics and the need for more urban-targeted indicators [17]. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency now considers the environmental objectives equivalent or connected to the ecological dimension of the SDGs [18].

SDG 11 is to “make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable”. More specific goals are pinpointed in the New Global Agenda [16]. The challenge of adapting cities to general, global goals remain [19]. Not only are cities complex structures, but they are also physical manifestations of a large number of needs ideally coordinated in relation to a multitude of functions. When urban planners strive to fit all needs into the same politically negotiated plans, goal conflicts become evident which makes planning a “wicked” problem, or task [20].

In the Swedish context, physical planning is conducted primarily through the comprehensive plan. It is formulated to clarify long-term physical planning goals and to guide and enhance the planning process [21]. Once during each electoral period, municipal policy makers are obliged to process the plan and, if needed, decide on updates. Consultations with the public may also influence revisions. Regional offices of the national oversight authority, the County Board (Länsstyrelsen), oversee the plans so that they adhere to national legislation. Still, comprehensive plans are not legally binding. The development of singular residential or industrial areas are guided by the detailed plan, where sharp decisions regarding environmental standards and ecosystem services are to be taken [22]. In this article, we focus on comprehensive plans, since these documents set general goals for a sustainable municipal development.

There is no standardised format for Swedish comprehensive plans. As long as the plan ”contains what the law requires and its meaning and consequences can be clearly read”, municipalities are free to formulate their plans according to its own needs [9]. In some plans, general goals and ideas are held forth, while others rely on maps and statistics. Some are organised according to administrative or geographical boundaries within the municipality, others focus on visions transgressing municipal administrations or on functions such as “water supply”. The plans tend to change character to respond to current development ideas. Schubert et al. [22], for example, demonstrate how over the decades Swedish comprehensive plans have shifted from being narrow in scope to more holistic and systemically oriented, especially regarding how ecosystem services (or their conceptual forebearers) are presented.

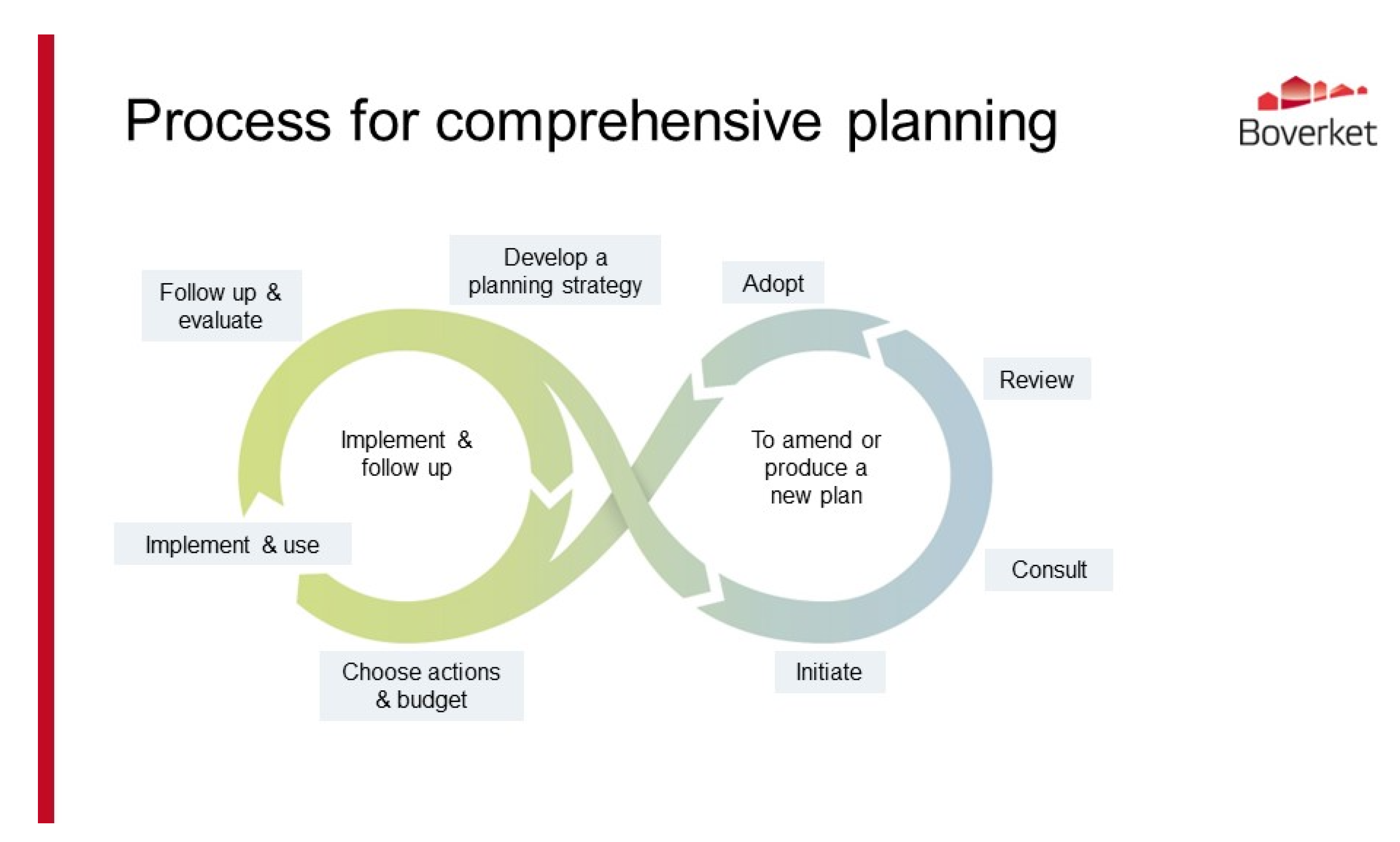

Swedish comprehensive plans normally have a lifespan of approximately a decade. They are renegotiated and subject to revisions following changes in the municipal government. New versions may be under review for several years before being politically adopted and implemented. In all, this means that comprehensive plans are “moving targets” for analysis (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Swedish comprehensive planning process (courtesy of Boverket, The Swedish National Board of Housing, Building and Planning, 2023).

3. Methods and Materials

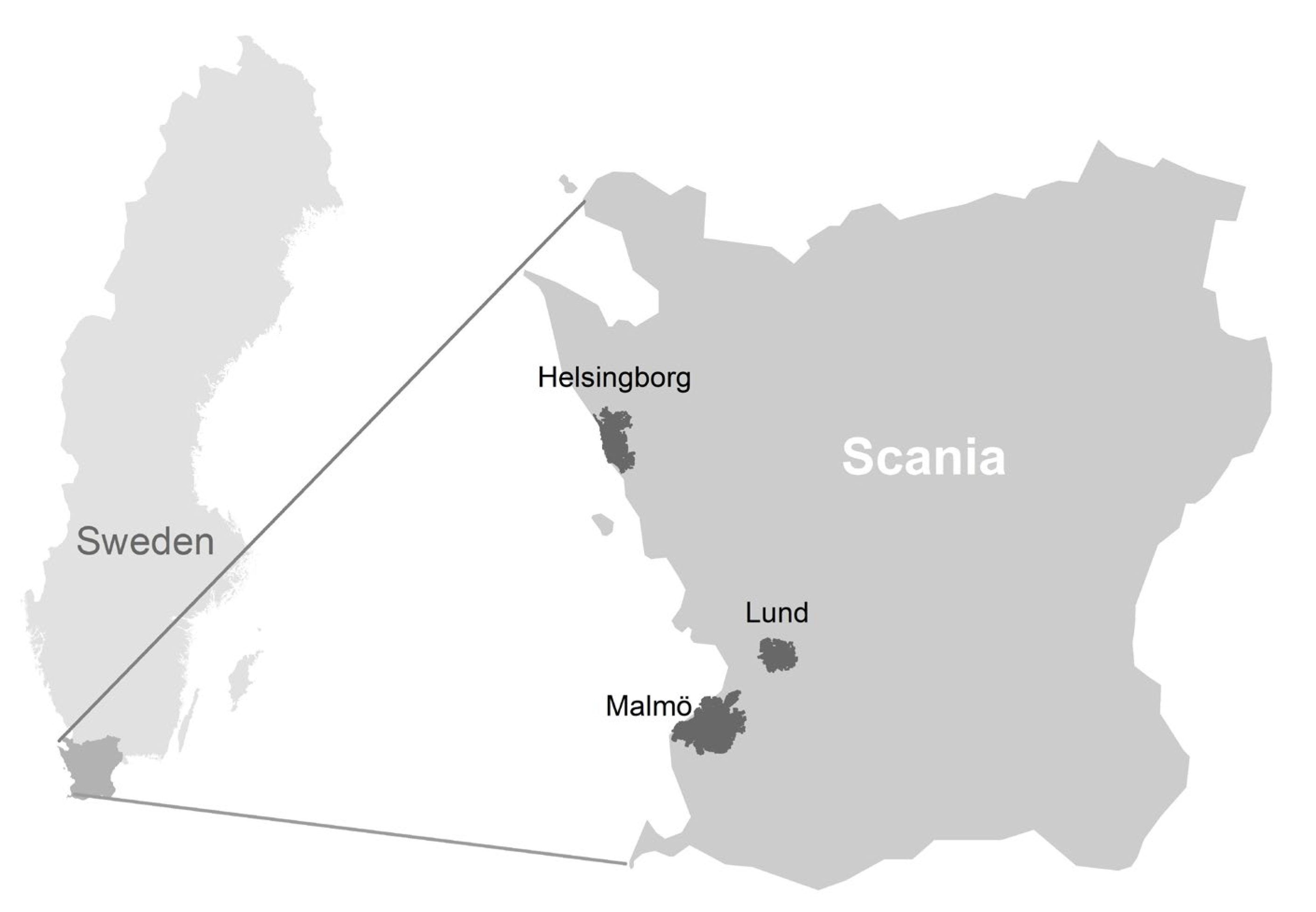

This article represents one substudy of a larger, collaborative and transdisciplinary research project called Dense Healthy City (Tät sund stad). The overarching aim of the project was to develop knowledge and practices for planning for denser, healthier and greener cities. The project involved scholars and public servants, mainly urban planners, from Malmö, Lund and Helsingborg in the densely populated county of Skåne, southernmost Sweden (see Figure 2). Hence, these cities were chosen as purposive samples. To articulate fields of inquiry, researchers and public servants participated in an iterative process regarding the formulation of relevant challenges and topics and the collection of empirical material, as well as the publication and dissemination of results. The research team invited municipal and regional public servants engaged in urban planning to a one-day seminar in Lund, October 2019. All participants were given time to present their work related to sustainable development, densification and ecosystem services. Discussions followed, where urgent issues in municipal planning were pinpointed. Three of the researchers took notes during the discussions, later merged to one set of notes. Plans for researchers and public servants to collaborate in person in 2020 and 2021 were severely complicated because of the COVID-19 restrictions. The restrictions continued into the spring of 2022. Instead, we met through a series of online meetings, discussions and virtual city-walks with municipal and regional planners. Based on issues that came up during the discussion, we decided to conduct a qualitative content analysis of the comprehensive plans of each municipality.

Figure 2.

Map over Sweden representing the Scania region and the three case municipalities. Courtesy of Kristoffer Mattisson, Lund University.

We chose to analyse the comprehensive plans not because they are objective “containers of data” [23]. However, they are relevant as publicly approved documents to capture what is politically viable in each municipality. The plans are written to reflect ideas and ideals with which to form the physical reality, and should, ideally, function as documents intended to eventually be transformed into reality, or “trigger chains of interactions” [24]. The ambiguities, unclarities and the disposition of the comprehensive plans provide information of where tensions regarding planning for dense, green and healthy cities are to be found.

During the study period, 2019–2022, Helsingborg municipality had a comprehensive plan from 2010 and adopted a new plan in 2021. Malmö municipality worked according to a plan from 2018 and published a new plan for review online in 2022, though it is still not politically adopted. Lund municipality’s plan from 2018 is still in use. A new plan is under review, though not yet published (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Statistics regarding the case municipalities according to Swedish official statistics (www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se accessed on 9 June 2023). The statistics for the green area per person were last updated in 2015 and likely decreased since then due to densification.

The three comprehensive plans in use during the initial period of the project were first read extensively by the corresponding author. All passages of sustainability and densification in proximity of ecosystem services and related concepts were marked. Following a qualitative content analysis routine [25], a primary categorisation of patterns was discussed among the three authors. A second detailed reading was then performed by the primary author during which more specific codes were marked manually in the documents and grouped in themes, called findings. Four findings were decided on by the authors in collaboration. Relevant excerpts were translated to English. In a final round of analysis, we compared the findings from the previous plans to the updated plan of Helsingborg [26] and the suggested new version of Malmö [27]. The first finding, big goals, serves as an introductory category, while the last, priorities, also is a meta-commentary to the result of the analysis as a whole.

We now present the three case municipalities in question, their geographical circumstances, their main planning challenges, how their comprehensive plans were structured, and then continue on to a closer reading focusing on densification and ecosystem services.

3.1. Malmö—Post-Industrial City on the Seashore

Malmö is the third largest city in Sweden with a population of approximately 357,000, located in the southernmost part of Scania. To the west and northwest, former brownfields are being rebuilt as residential areas. Malmö is surrounded by the most productive soils in Europe. The city expanded rapidly with high-rise residential projects in 1965–1975. Larger roads were constructed, acting as barriers for wildlife and insects. Though nick-named the “City of Parks” [28], Malmö contains among the lowest green space quota per inhabitant in Sweden [29,30]. With proximity to the waterfront, Malmö is susceptible to flooding during heavy rains and to rising sea levels. The initial comprehensive plan consisted of an urban development vision, where goals and priorities were emphasised, cut down to specific strategies that were thought to end up as directions for physical planning. Sections in the plan contained perspectives such as “providing housing”, “higher education, research and development”, “dense city”, “the bike city” “water resources and infrastructure for water”, and “climate adaptation” [31]. Since 2003, Malmö has also had a “green plan”, ramifying green structures in the city and specifying the qualities and contents of biotopes intended to be kept and developed. The green plan is intended as a basis for physical planning, in a similar manner as the strategies, but it is not legally binding [32].

3.2. Lund—Medieval Town in Expansion

Approximately 20 kilometres northeast of Malmö is Lund, a university town centred around a medieval cathedral. It has a population of 128,000 of which many are students at the university. In concentric circles, more recent residential and industrial areas have spread over the landscape. Lund is currently expanding with mostly low-rise buildings to the east, and new areas are planned to be built to the south. The landscape surrounding the city is characterised by intensive agriculture and large-scale road structures. The main national railroad runs through the city centre. The comprehensive plan from 2018 consists of two main parts: (1) plan strategy, where point of departures and general goals are specified; (2) land-use and considerations related to land-use issues and water-related issues. The plan also contains a section with beslutsunderlag (basis for decisions) where social, economic and environmental consequences are addressed [33,34]. Lund also has an “action plan for green structure”.

3.3. Helsingborg—A Squeeze between Land and Sea

Helsingborg is a city in the north-western part of county Skåne. It has a population of 151,000, and it is located where Öresund is at its most narrow. With the ferry harbour and connecting railroad, Helsingborg is a traffic juncture for travellers, as well as goods. During the 20th century, industrial and residential areas were eventually built on landfills, expanding the city north-westwards into Öresund. The city has also expanded extensively with residential areas stretching around to the north and east. Two major roads, E6 and E4, connect to the city. A challenge built into the landscape and the history of the city, is the fact that trains, car traffic and ferries meet on the narrow strip along the coast. Helsingborg’s previous plan was in use till the end of 2021. It consisted of a vision for the city, a section called future challenges, a section with strategies for success and, finally, three profile areas: meeting places, residential areas and logistics [35]. The new plan [26], consists of developmental directions, land and water usage, urban areas, national interests, municipal areas of special care, consequences and dialogues.

4. Results

4.1. Big Goals—General Urban Sustainability and Densification

The three case cities all have high ambitions when it comes to urban sustainability, related to the SDGs, the Swedish environmental objectives and the New Urban Agenda. Malmö planned to be “a resource-efficient society and [that] ecological sustainability means to secure and satisfy basic human needs in the long run” [31] (p. 4), and later that is should be a “close-by, dense, green and functionally integrated city” [27]. Helsingborg stated that “sustainable development means to use human and natural resources consciously and in a balanced fashion through taking social as well as environmental and economic aspects into consideration” [35] (p. 12). Lund has equally high ambitions: “When Lund grows, it will happen in a responsible way. Through densification, we economise with the good [arable] soil and create a resource-efficient and sustainable society” [33] (p. 1). The connection between general sustainability and densification was present in all the documents. The goal of densification, in the way formulated by Lund, is

“to conserve land and resources while at the same time creating socially and economically sustainable urban environments that are attractive, green and feel safe for us and [for] future generations. Through densification the possibility is there to enhance meeting places and urban life, build away barriers, create mixed land-use, developing the green values and increasing attractivity and enhancing the identities of suburbs [33]”(p. 23).

Helsingborg, in its previous plan, started out with a vision of the city in 2035, then continued to a number of themes. Densification was expressed as a solution to related environmental issues:

“Densification means building within present residential areas, and can be done in different ways […]. Densification means wins for the environment since we economise with our agricultural land and improve energy consumption as present infrastructure is used in a more efficient way [35]”(p. 14).

Helsingborg states that through their current plan, the municipality shows “what possibilities there are to develop, enrich and densify” [26]. In their current plan, Malmö declares that it has “high environmental ambitions, partly through densification which creates conditions for a sustainable mobility and conserves agricultural land” [27]. As these examples show, densification is framed as the nearest-at-hand solution to living up to long-term sustainability. Malmö achieved the closest holistic understanding of ecosystem services, when stating: “Well-functioning ecosystems are the basis for sustainable urban development. Humans are completely dependent on ecosystem services, which include all products and services that nature offers and which provides to the wellbeing and survival of humans” [31] (p. 35). This quite radical stance is not present in the current plan.

The inherent goal conflict is to facilitate economic prosperity and growth, catering to equity, environmental justice and ecosystem services, while avoiding undermining the supportive systems upon which the city depends. In the documents, it is obvious how planners struggle to sort out tensions between these needs, in a way that reflects the immense tangle of the task. Oftentimes, this is solved by stating that all things good support each other. Helsingborg [35] exemplified the inherent positivity claiming that

“A continuous urban development creates possibilities to minimise our impact on the climate. Simultaneously, future climate change with rising sea levels and higher temperatures affect our possibilities to develop cities and [smaller] societies. […] The challenge lies in decreasing our exhausts and limit our energy consumption while at the same time economising with land, while simultaneously a continuous growth has to be stimulated to make a robust and sustainable society possible”(p. 13).

Whether “continuous growth” was considered economic or spatial was not clarified. Possibly, it related to municipalities’ need for increasing tax revenues to support future development of the city.

Inherent goal conflicts are discarded through what comes forth as positive affirmations: “Using land resources efficiently [i.e., densifying] also means that we will get more space; space for more residential buildings, more green spaces, enterprises and service, which all create surplus value for the areas in question” [35] (p. 14). In this formulation, densification was presented as a means for achieving “more” of several spatially demanding benefits at once. But can this really be done? This brings us to the next finding: The issue of scale.

4.2. Scale

How far does a municipal comprehensive plan reach, spatially? The straightforward answer is as far as the municipality’s borders, where the planning jurisdiction ends. Within this border, the municipality is obliged to plan for the land-use needed. In this respect, densification is an efficient way to make “more” of the limited space, if it can be done inside the city. The real challenge when planning för sustainable development, however, is often tied to systems and functions outside the city’s border. The effect is that planning for densification could, in theory, be a way to enhance sustainability factors in the city while simultaneously increasing pressure on surrounding ecosystems.

However, the future prosperity of any urban structure is dependent on supporting and provisioning ecosystem services for the city (see Table 2). These services are mainly produced in the hinterlands or on a global scale, which the comprehensive plans are not intended to address, thus omitting the most fundamental sustainability issue regarding densification and ecosystem services: the fact that denser cities contain more people, who all need externally produced resources.

Table 2.

Ecosystem services in comprehensive plans mainly refer to the internal ecosystem services, in the city, while as external ecosystem services often are omitted or only briefly mentioned.

However, the relationship between the urban and the rural did not go entirely unmentioned. Malmö, for example, previously envisioned a future city where…

“… there is room for a lush biological diversity both among species and in natural environments. The exchange between city and countryside has increased and the agricultural landscape is an arena for small-scale entrepreneurship. Agriculture is performed mainly organically and the hinterland is an asset for local food production. Taken together, Malmö is a city where the ecosystem services are beneficial to both humans and nature [31].”

In the current plan, Malmö explicitly adheres to the SDGs but puts more emphasis on the citizens’ everyday experience of sustainable development than the ecological and systemic [27]. Malmö also had plans to become a “close city”, a concept equivalent to 15 min cities. In such a city, all daily activities should be possible to reach by foot or bike within a quarter of an hour [36]. Malmö related to saving resources: “Resources should be saved through building the city denser. Malmö is a city which can be “close” from several perspectives. The dense city should be close and surface efficient. Malmö should be built as a mixed-function city for an intense and rich city life” [31] (p. 8). In the current plan, it is stated that the city should “grow inwards” and be “flexible and surface efficient” [27]. There are no explicit goals in any of the plans regarding limiting growth, apart from avoiding building on arable land. In Lund, growth is addressed as follows:

“In later years, Lund municipality has grown with 14,000 inhabitants, and the population is expected to continue increasing. The carrying strategy is that Lund and surrounding [smaller] villages shall grow from the inside and out. A denser city gives a resource efficient society and an enhanced social and economic exchange [33]”(p. 69).

This strategy does not offer clarity regarding the limits to urban growth as such or regarding the relationship between growth and time. Helsingborg [35] (p. 12) projected a population increase of 30,000 new citizens over 25 years. The city planned to “grow with consideration and reflection, with densification within already built areas and not on high-qualitative greenery” [35] (p. 26). The three cities did and still do, to some extent, acknowledge the importance of not sprawling onto top-quality arable land but with different levels of specification and prioritizations. Lund [33] (p. 23) states the fact but does not say how to hinder urban sprawl. Helsingborg [35] (p. 34) previously recognised the problem but also opened up for satisfying the needs of the entrepreneurial economy and its need for infrastructure. In the current plan, Helsingborg states that “[c]onserving land- and water resources means that we use land more efficiently, for example through surfaces used for several aims or through densification” [26]. Malmö addressed the issue of scale more sharply, through the decision not to allow more buildings outside the ring-road [31] (p. 34): “Malmö has, during the last decades, mainly grown inside the Outer Ring-road, and has mainly been built increasingly dense. The dense city is more resource efficient than one sparsely built, and through letting the city grow inward, valuable agricultural land can be saved for the future”. This goal is repeated in the recent plan.

The issue of scale is implicit in all planning for sustainable urban development. However, as much as the comprehensive plans analysed here are ambitious in terms of addressing challenges regarding densification and ecosystem services, the framing is problematic. All three municipalities express a need for expansion and growth spatially, as well as in terms of population and economic development. When it comes to ecosystem services for the city, a need to preserve high-quality agricultural land is repeatedly mentioned. Occasionally there are also suggestions on how to connect the city with its surroundings through “corridors” of greenery to benefit biological diversity and health-related recreational qualities, which respond to the needs for ecosystem services in the city. All things taken together, the authors of the comprehensive plans and the politicians who are to accept them are put to the task of making all functions and needs matter, preferably simultaneously though also over the foreseeable future. This brings us to the third theme in the analysis of the plans, that of timeframe.

4.3. Timeframe

Malmö previously addressed the possibilities and limitations of the comprehensive plan itself as follows:

“At the same time, development is dependent on a long row of factors over which the municipality has no influence. For the plan to have as big impact as possible, it is important that its directions permeate all planning processes in the municipality [31]”(p. 20).

In the recent version, this self-reflective voice is less prominent. It says that the comprehensive plan should be viewed from a long-term perspective, and parts of the plan may be implemented far off in the future [27]. All three cities, however, mention long-term and future.

In its previous plan, Helsingborg [35] related to a successful past: “We have had a period of growth and development which has resulted in an extensive building of residential houses. The urban planning of today is the result of long-term and conscious planning”. In their present plan, 2050 is held forth as a timeframe. Lund [33] (p. 43) connects issues of space and time when planning for the towns outside the city: “Strengthening a green infrastructure is an important prerequisite for densification in the [smaller] towns in the municipality to happen in a sustainable way, so that citizens also in the future will be able to gain from the ecosystem services on which humans are dependent”. Timeframe, spatial scale and social aspects tend to be mentioned simultaneously. Malmö [31] (p. 19) wrote that “to achieve a dense, resource conservative and mixed-function city that is socially kept together, a high level of holistic perspective and mutual accordance is needed. The long-term utility and a holistic perspective on the development of the city have to be prioritised when different interests are to be weighed against each other”.

When it comes to densification in relation to climate change and raising sea levels, the coastal cities of Malmö and Helsingborg are most affected, and also those which have to be precautious regarding the resilience of future densification projects. In both cities, brownfields close to water were designated for residential areas. The addressing of these challenges, though, were slightly evasive. All three cities refer to their long history, while their future remains vague. The question raised here is: How does the idea of “sustainability” relate to the idea of “long term” in comprehensive planning? While the lifespan of a municipal plan may be 10–15 years, the physical agglomeration of a city will remain for at least a few centuries into the future, preferably continuing for ever. Still, the physical planning does not seem to be able to take long-time perspectives into account if sustainably means “into eternity”.

4.4. Priorities

The fourth, and last, theme is the issue of how priorities are addressed. According to the plans, the cities will continue to grow, although not at the cost of their agriculturally productive hinterlands. The economy will flourish while causing neither increased traffic nor air pollution. The cities aim to be sustainable, resource efficient, equitable, economically and socially vibrant, as well as peaceful. Malmö [31] (p. 8) was illustrative: “Malmö should be a socially, environmentally, and economically sustainable city and an attractive place to live in, visit and work in. The three sustainability dimensions collaborate and are mutually dependent”. A few pages below, Malmö stated “Growth-enhancing actions contribute to welfare for the citizens, more job opportunities and subsistence are pivotal for the development of the city” [31] (p. 12). In the new plan, Malmö suggests under the headline Park and nature: “The area of park and nature should increase. More greenery should be aimed at. The number of trees in the city shall increase. Expansion should happen with the less possible negative impact on present values of nature and recreation” [27].

The question is how this is simultaneously viable. Densification is held forth as the main strategy to tackle challenges when cities plan to grow and expand. Helsingborg [35] (p. 14), for example, listed the benefits of densification, which according to the plan would “save agricultural land and improve public transportation, make travelling easier, give better air quality, better residential environments, strengthen businesses, give more job opportunities and more tax revenues, which can be invested in the environment, [which] will give a better public health”. In the new plan, this attempt to capture the general good is more subtle: “When we densify, it should contribute to quality of life through creating proximity, but densification should not happen on the cost of other qualities in the everyday of people” [26]. The contradictions remain unresolved:

“The vantagepoint for this suggestion [plan] is sustainable urban and rural development. We create opportunities for growth with new residential buildings as well as areas where enterprises can develop. Simultaneously, our mobility and our transportations should be sustainable, there should be a preparedness for climate change, [and] we should conserve agricultural land and develop ecosystem services (ibid.).”

Lund stated that “Densification is the main direction. Development and vitalisation through densification should also enhance social and green values” [33] (p. 24), and went on to address the conflicting interests: “Densification is often pinpointed as a threat to parks and other green values in the city. Every single densification project can lead to a principal struggle between the different interests where there will be a balance between high building density and the green surfaces” [33] (p. 27). Malmö was the one city of to address conflicting interests explicitly in its previous plan:

“Goal conflicts: There can be goal conflicts between different strategies in the comprehensive plan. In most cases these conflicts can be solved through a holistic perspective, collaboration and compromise. In several cases, the conflicts are less inside the comprehensive plan and more between the comprehensive plan and conventional thinking, outdated guidelines and rules, sectorised financial structures etc. Conventions, habitual methods and internal regulations have to be questioned. Even existing norms, rules and legislations might have to be re-evaluated to enable a sustainable urban development [31]”(p. 20).

The way that priorities are handled sometimes border on the incomprehensible. Malmö, with its relatively explicit way of addressing conflicting goals, wrote: “Compromises are pivotal, as well as sometimes letting go of optimal spatial requirements. Dense solutions can in some cases be unavoidable but seen in a larger [societal] economic perspective, they can still be preferable” [31] (p. 34).

Lund suggested so-called compensation: “If densification in the green spaces in the [smaller] towns are done, the principle of balancing priorities can be practiced, which includes to compensate for values that disappear or are damaged when an exploitation is done” [33] (p. 27). Such compensations include, for example, the planting of new trees or installing green roofs, to compensate for the greenery removed for new buildings and infrastructure. Lund also expresses how newly planned areas can and should be multifunctional. The following passage illustrates how greenery is thought to provide a row of functions:

“A way of including more greenery, water and ecosystem services in a dense urban environment is to create multifunctional spaces where the same area can fulfil functions for example for day-water treatment, traffic security, recreation and plant- and animal life. Increased urbanisation and densification in the cities demand increased requirements to fit in more functions in the same space. Obviously, not all functions can always be combined, for example can day-water supply [sic] not always be combined with recreative spaces with close contact with the water, where such contact is a prerequisite, when the day-water often is of lacking quality. But with a thought-through visualisation of the public urban spaces, they can provide more recreative and ecological functions than today, even if the city is densified [33]”(p. 45).

When there is no way of avoiding the destruction of a green space, municipalities may compensate for it under what has sometimes been framed as voluntary compensation [37]. The idea is that a green area within the same municipality is to be protected as a compensation. Helsingborg previously lifted forth this “principle of balance”: “During [new] exploitation the principle of balance should be applied. This implies that we primarily should avoid destroying or damaging natural values or ecological values. If it turns out that this is not doable, disturbance should be minimised and values substituted with a similar function and extent as close to the source as possible” [35] (p. 31).

Among our three cities and five plans, Malmö most clearly addressed that residential housing, work places and societal services had the highest priority but, in the next sentence, stated that “the dense and green city can only be made reality on the cost of the city’s impervious surfaces” [31] (p. 19, italics in original). However, in the new plan, contradictions are still present despite high standards:

“Densification of Malmö should not happen [at] the cost of the green and blue environments of the city. To the contrary, the city should be greener, both regarding the amount of greenery, quality of greenery and the experience of greenery. Biological diversity is a vital resource and pivotal for ecosystems to be of use, when for example purifying water and air, capturing carbon and pollinating our crops. The value of biological diversity should be integrated in planning and developing the city. Green and blue environments should be conserved, developed and created [27].”

5. Conclusions and Discussion

This analysis reveals that all of the comprehensive plans had high ambitions related to densification and ecosystem services. However, there are systemic and recurrent obstacles to constructively and realistically combining these. The unclarities remained in the updated versions of the plans. These obstacles, we found, were related to the categories of scale, timeframe and priorities.

We investigated in what terms the planners connect densification and ecosystem services to sustainable urban development in general. We also analysed how planners articulate how densification is to be utilised to create green, healthy cities. Furthermore, how did and currently do planners negotiate discontinuities between densification on the one hand and ecosystem services on the other?

Primarily, there is the issue of scale. The planners mainly address local, regulating and cultural aspects of ecosystem services [38]. Planning, in the way it focuses on the geographical area over which the municipality has jurisdiction, addresses issues of ecosystem services in the city. A city is a “constructed whole” [39]. Flows of materials in and out of the city can seldom be pinpointed geographically and, thus, not entirely handled within a certain geographical or judicial space. Because of the “constructed whole”, the supporting and provisioning ecosystem services that work for the city are less explicitly mentioned in the comprehensive plans (see Table 2). This reproduces an anthropocentric conception of ecosystem services as related to comfort and aesthetics for urban residents. The comprehensive plans, as they are currently formed, have difficulties addressing issues related to protecting or planning for ecosystems for the city, though these are pivotal for the survival of the city and the humans living in it. As long as ecosystem services for the city are not more clearly taken into account when outlining visions for planning for densification, sustainability will be no more than cosmetics. Zinkernagel et al. [17] pointed out that cities’ capacity to deal with “out-of-boundary challenges and externalities” is a central obstacle to reach the SDGs.

The second issue is that of timeframe. What does “sustainable”, especially in the formulation “sustainable growth” actually mean? Terms like “long term” and “over time” hint to something durable and stable, but they also efficiently blur the timelines wherein planning for sustainability should ideally work. A discussion on this should be of central interest to municipalities which are taking sustainability seriously.

The last but most urgent issue is that of priorities. A major challenge is that densification does not easily comply with the idea of sufficient green spaces in the city [40]. In the plans, the idea of densification takes on close to magical propensities, where all good things, within the existing paradigm, are promoted simultaneously. Goal conflicts are addressed evasively. Systemic contradictions between, for example, urban growth and natural resources from near and far, are not addressed. There is an obvious risk that ecosystem services are weighted or even “played off” against each other [41]. BenDor et al. argue that both synergies and trade-offs need to be accounted for in the planning process for a more optimal outcome [42].

It is our conclusion that comprehensive plans tend to be documents where all things good, such as densification and increased quality of ecosystem services, as well as economic growth, are intended to add to general sustainability. This reflects a confusion larger than that of a single municipality and should be further discussed by research and handled by politicians. There is no way that human urban dwellings, dense or not, can continue to grow unlimited, without compromising the integrity and functions of ecosystem services, even if growth itself happens within the human-made geographical boundaries of a municipality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: E.L.J., E.M. and J.A.O.; methodology, E.L.J.; formal analysis, E.L.J.; investigation, E.L.J.; writing—original draft preparation, E.L.J.; writing—review and editing, E.L.J., E.M. and J.A.O.; project administration, E.M.; funding acquisition, E.M., E.L.J. and J.A.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Project Densifying the Cities without Increased Environmental Health Burden—Is It Attainable? Was financed by the Swedish Research Council FORMAS, Targeted Call Housing Policy for Social Sustainability 2017, project number: 2018-00047.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The documents analysed in this study are available online according to the reference list.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our gratitude to the public servants of Malmö, Lund and Helsingborg municipalities and to Peter Groth from the regional Scania authority, who shared their perspectives as the project started. We are also grateful for the constructive comments from our colleagues at the seminar at the Unit for Human Geography, Gothenburg University. We wish to express our gratitude to Victoria Nordholm at the Swedish National Board of Housing, Building and Planning, and to our colleague Kristoffer Mattisson, Lund University, who provided us with the figure of the planning process and the map of Scania, respectively.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Matlock, A.S.; Lipsman, J.E. Mitigating environmental harm in urban planning: An ecological perspective. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 568–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, P.R.; Conroy, M.M. Are We Planning for Sustainable Development? J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2000, 66, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Neste, S.; Royer, J.-P. Contested densification: Sustainability, place and the expectations at the urban fringe. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 975130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahi, Z.; Hashemi, M.; Bameri, S. Environmental pollution, economic growth, population, industrialization, and technology in weak and strong sustainability: Using STIRPAT model. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 1105–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næss, P.; Saglie, I.-L.; Richardson, T. Urban sustainability: Is densification sufficient? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aagaard Hagemann, F.; Randrup, T.B.; Ode Sang, Å. Challenges to implementing the urban ecosystem service concept in green infrastructure planning: A view from practicioners in Swedish municipalities. Socio-Ecol. Pract. Res. 2020, 2, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmqvist, T.; Setälä, H.; Handel, S.N.; Van Der Ploeg, S.; Aronson, J.; Blignaut, J.N.; Gomez-Baggethun, E.; Nowak, D.J.; Kronenberg, J.; De Groot, R. Benefits of restoring ecosystem services in urban areas. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Barbir, J.; Sima, M.; Kalbus, A.; Nagy, G.J.; Paletta, A.; Villamizar, A.; Martinez, R.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Pereira, M.J.; et al. Reviewing the role of ecosystems services in the sustainability of the urban environment: A multi-country analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boverket. Översiktsplanen (The Comprehensive Plan). 2023. Available online: https://www.boverket.se/sv/PBL-kunskapsbanken/planering/oversiktsplan/oversiktsplanen/ (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Pont, M.B.; Haupt, P.; Berg, P.; Alstäde, V.; Heyman, A. Systemic review and comparison of densification effects and planning motivations. Build. Cities 2021, 2, 378–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D. The Science—Society Interface in the Urban Environment: A Policy Perspective. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2016, 24, 715–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marino, M.; Tiitu, M.; Lapintie, K.; Viinikka, A.; Kopperoinen, L. Intergrating green infrastructure and ecosystem services in land use planning: Results from two Finnish case studies. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 643–656. [Google Scholar]

- Khoshkar, S.; Hammer, M.; Borgström, S.; Dinnétz, P.; Balfors, B. Moving from vision to action—Integrating ecosyustem services in the Swedish local planning context. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. De Svenska Miljömålen (The Swedish Environmental Goals). 2021. Available online: https://sverigesmiljomal.se/miljomalen/ (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Nordin, A.; Hanson, H.I.; Olsson, J.A. Integration of the ecosystem services concept in planning documents from six municipalities in southwestern Sweden. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (Ed.) New Urban Agenda: Quito Declaration on Sustainable Cities and Human Settlements for All; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zinkernagel, R.; Evans, J.; Neij, L. Applying the SDGs to Cities: Business as Usual or a New Dawn? Sustainability 2018, 10, 3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naturvårdsverket. Sveriges Miljömål och Agenda 2030. 2021. Available online: https://www.naturvardsverket.se/om-miljoarbetet/sveriges-miljomal/ (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Valencia, S.C.; Staff, C.A.; Pettersson, S.; Risfelt, L. Localisation of the 2030 Agenda and Its Sustainable Development Goals in Gothenburg, Sweden; City Executive Office: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jepson, J.E.J. Sustainability Science and Planning: A Crucial Collaboration? Plan. Theory Pract. 2019, 20, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, S.C.; BenDor, T.K. Ecosystem services in urban planning: Comparative paradigms and guidelines for high quality plans. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 152, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, P.; Ekelund, N.G.A.; Beery, T.; Wamsler, C.; Jönsson, K.I.; Roth, A.; Stålhammar, S.; Bramryd, T.; Johansson, M.; Palo, T. Implementation of the ecosystem services approach in Swedish municipal planning. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2018, 20, 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, L. Using Documents in Social Research. In Qualitative Research; Silverman, D., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2019; pp. 185–199. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsson, K. Analysing Documents through Fieldwork. In Qualitative Research; Silverman, D., Ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 167–183. [Google Scholar]

- Hecker, S.; Wicke, N.; Haklay, M.; Bonn, A. How Does Policy Conceptualise Citizen Science? A Qualitative Content Analysis of International Policy Documents. Citiz. Sci. Theory Pract. 2019, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsingborg Municipality. Översiktsplan 2021 (Comprehensive Plan). 2021. Available online: https://helsingborg.se/trafik-och-stadsplanering/planering-och-utveckling/oversiktsplanering/gallande-oversiktsplaner/oversiktsplan-2021/ (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Malmö Municipality. Översiktsplan för Malmö (Granskningshandling). 2022. Available online: https://malmo.se/download/18.187ac425180513e4ebc216ba/1660630843222/ÖP%20granskningshandling%20juni%202022u.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Visit Sweden. 2021. Available online: https://visitsweden.com/where-to-go/southern-sweden/malmo/malmo-city-parks/ (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Statistics Sweden. Green Space and Green Areas in Urban Areas 2015; Statistics Sweden: Solna, Sweden; Örebro, Sweden, 2015.

- Malmö Municipality. Grönyta per Invånare (Green Space per Inhabitant). 2020. Available online: http://miljobarometern.malmo.se/miljoprogram/stadsmiljo/grona-och-bla/gronyta-per-invanare/ (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Malmö Municipality. Översiktsplan för Malmö (Comprehensive Plan for Malmö Municipality). 2018. Available online: https://malmo.se/Service/Var-stad-och-var-omgivning/Stadsplanering-och-strategier/Oversiktsplan-och-strategier/Oversiktsplan-for-Malmo.html (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Malmö Municipality. Grönplan för Malmö; Malmö Municipality: Malmö, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lund Municipality. Översiktsplan (Comprehensive Plan). 2018. Available online: https://www.lund.se/trafik--stadsplanering/oversiktsplan/ (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Lund Municipality. Ny Översiktsplan 2024—Arbete Pågår. 2023. Available online: https://lund.se/stadsutveckling-och-trafik/detaljplaner-och-oversiktlig-planering/oversiktsplan-2024---arbete-pagar (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Helsingborg Municipality. Översiktsplan 2010 (Comprehensive Plan). 2010. Available online: https://helsingborg.se/trafik-och-stadsplanering/planering-och-utveckling/oversiktsplanering/gallande-oversiktsplaner/oversiktsplan-2010/ (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Pozoukidou, G.; Chatziyiannaki, Z. 15-Minute city: Decomposing the new urban planning Eutopia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, H.I.; Alkan Olsson, J. Uptake and use of biodiversity offsetting in urban planning—The case of Sweden. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 80, 127841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhearson, T.; Andersson, E.; Elmqvist, T.; Frantzeskaki, N. Resilence of and through urban ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 12, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärrholm, M. The Scaling of Sustainable Urban Form: A Case of Scale-related Issues and Sustainable Planning in Malmö, Sweden. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2011, 19, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaland, C.; Konijnendijk van den Boch, C. Challenges and strategies for urban green-space planning in cities undergoing densification: A review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 760771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Haaren, C.; Albert, C. Integrating ecosystem services and environmental planning: Limitations and synergies. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2011, 7, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BenDor, T.K.; Spurlock, D.; Woodruff, S.C.; Olander, L. A research agenda for ecosystem services in American environmental and land use planning. Cities 2017, 60, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).