Determinants of Corporate Water Disclosure in Indonesia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

3. Data and Method

4. Results

5. Discussions

5.1. The Effect of the Existence of a CSR Committee on Water Information Disclosure

5.2. The Effect of the Independence of the Board of Commissioners on Water Information Disclosure

5.3. The Effect of Government Ownership on Water Information Disclosure

5.4. The Effect of Profitability on Water Information Disclosure

5.5. The Effect of Company Size on Water Information Disclosure

5.6. The Effect of Industry Type on Water Information Disclosure

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rakhmat, M.Z. Indonesia’s Growing Water Safety Crisis; Asia Sentinel: Hong Kong, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Trade and Investment Commission. Water Supply Challenges in Indonesia. 2016. Available online: https://www.austrade.gov.au/AWA-Wor (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Burritt, R.L.; Christ, K.L.; Omori, A. Drivers of corporate water-related disclosure: Evidence from japan. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 129, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.Q.A.; Lai, F.-W.; Shad, M.K.; Jan, A.A. Developing a green governance framework for the performance enhancement of the oil and gas industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

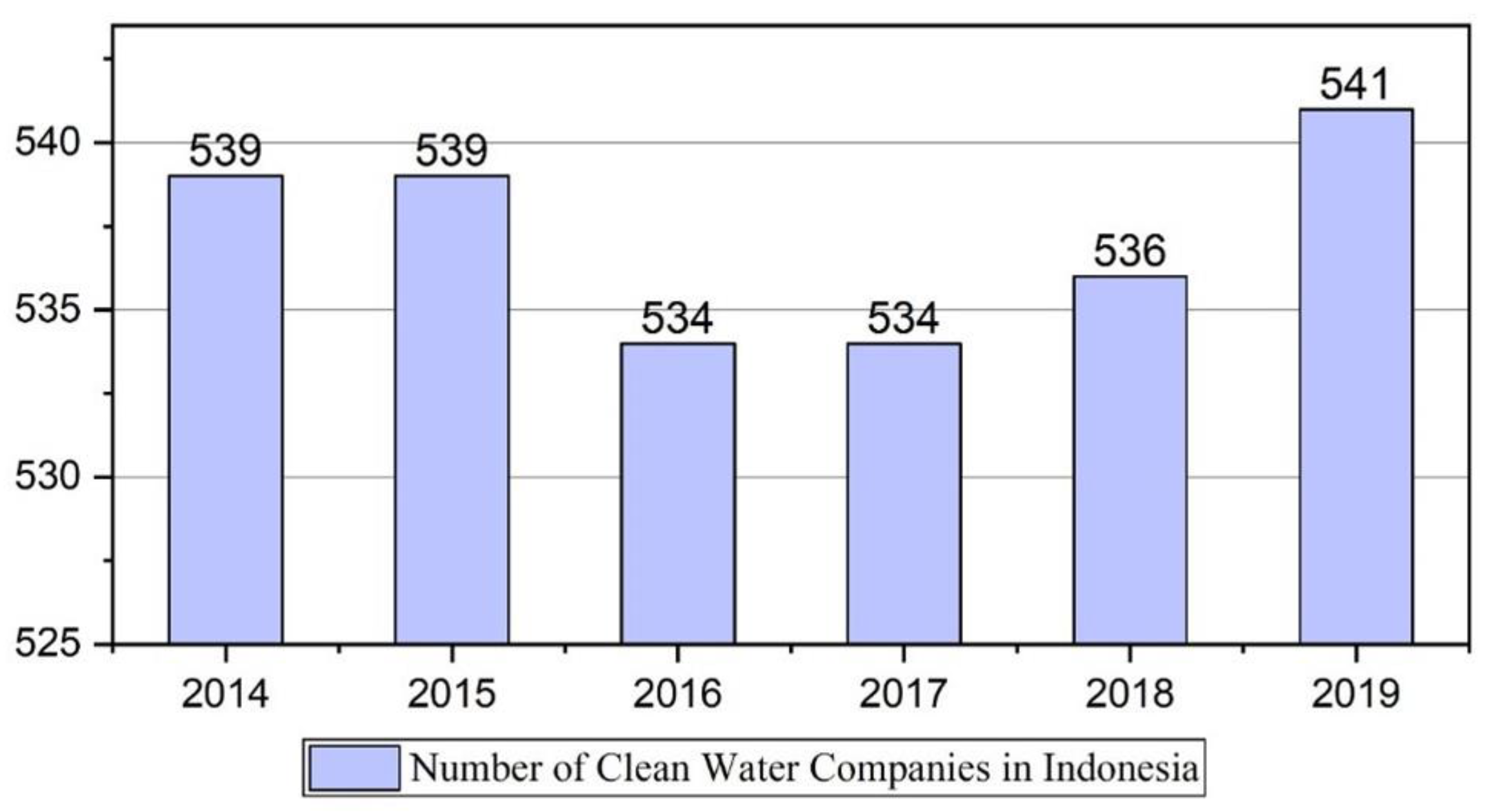

- Clean Water Statistics 2014–2019. Cent. Bur. Stat. 2020, 11–14. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2020/12/21/e467595b6ac962ed1488c287/statistik-air-bersih-2014-2019.html (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Cantele, S.; Tsalis, T.A.; Nikolaou, I.E. A new framework for assessing the sustainability reporting disclosure of water utilities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan. Data Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan (KLHK). 2021. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rY2jFHLJrtY (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Gunawan, J. Corporate social responsibility initiatives in a regulated and emerging country: An indonesia perspective. In Key Initiatives in Corporate Social Responsibility; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Liu, L.; Zeng, H.; Chen, X. Does water disclosure cause a rise in corporate risk-taking?—Evidence from chinese high water-risk industries. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 1313–1325. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, J.; Schulte, P. Corporate Water Accounting: An Analysis of Methods and Tools for Measuring Water Use and Its Impacts; UNEP; Pacific Institute: Oakland, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moving beyond Business as Usual. A Need for a Step Change in Water Risk Management; Deloitte: London, UK, 2013.

- WBCSD. Water for Business, Initiatives Guiding Sustainable Water Management in the Private Sector. Australian Team & Results. 2009. Available online: https://sswm.info/node/1104 (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Ben-Amar, W.; Chelli, M. What drives voluntary corporate water disclosures? The effect of country-level institutions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1609–1622. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Su, K.; Zhang, M. Water disclosure and financial reporting quality for social changes: Empirical evidence from china. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 166, 120571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tang, Q.; Huang, R.H. Mind the gap: Is water disclosure a missing component of corporate social responsibility? Br. Account. Rev. 2021, 53, 100940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, M.; Jin, Y.; Zeng, H. Does china’s river chief policy improve corporate water disclosure? A quasi-natural experimental. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 311, 127707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambang, W.; Djoko, S.; Djuminah, D.; Setianingtyas, H. Influence of political connection and corporate culture on water disclosure in indonesia. J. Talent Dev. Excell. 2020, 12, 1713–1721. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.-C.; Kuo, L.; Ma, B. The drivers of corporate water disclosure in enhancing information transparency. Sustainability 2020, 12, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeng, H.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, X. Water disclosure and firm risk: Empirical evidence from highly water-sensitive industries in china. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Lan, Y.-C.; Li, J.; Fan, H. Board gender diversity, national culture, and water disclosure of multinational corporations. Appl. Econ. 2023, 55, 1581–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salsabila, M.; Adhariani, D. “Artificial” gender diversity and public visibility: The case of corporate water disclosure in indonesia. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2022, 6, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Zeng, H.; Chen, X. Help or resistance? Product market competition and water information disclosure: Evidence from china. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2020, 11, 933–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, A.P.; Setiawan, D. Water disclosure in the agriculture industry: Does stakeholder influence matter? J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 337, 130605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, K.L.; Burritt, R.L. What constitutes contemporary corporate water accounting? A review from a management perspective. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hazelton, J. Accounting as a human right: The case of water information. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2013, 26, 267–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, A.P.; Setiawan, D. Impacts of stakeholder pressure on water disclosure within asian mining companies. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Sun, F.; Wang, B.; Shen, J.; Xu, J. Quality evaluation of water disclosure of chinese papermaking enterprises based on accelerated genetic algorithm. Res. Sq. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sari, T.K.; Cahaya, F.R.; Joseph, C. Coercive pressures and anti-corruption reporting: The case of asean countries. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C.; Larrinaga, C. Sustainability reporting: Insights from institutional theory. In Sustainability Accounting and Accountability; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2014; pp. 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Deegan, C. Twenty five years of social and environmental accounting research within critical perspectives of accounting: Hits, misses and ways forward. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2017, 43, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahaya, F.R.; Porter, S.A.; Tower, G.; Brown, A. Indonesia’s low concern for labor issues. Soc. Responsib. J. 2012, 8, 114–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.F.; Romi, A.M. The association between sustainability governance characteristics and the assurance of corporate sustainability reports. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2015, 34, 163–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfaya, A.; Moussa, T. Do board’s corporate social responsibility strategy and orientation influence environmental sustainability disclosure? Uk evidence. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 1061–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuente, J.A.; García-Sanchez, I.M.; Lozano, M.B. The role of the board of directors in the adoption of gri guidelines for the disclosure of csr information. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 737–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, G.; Parbonetti, A. The effect of corporate governance on sustainability disclosure. J. Manag. Gov. 2012, 16, 477–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Álvarez, I.; Pucheta-Martínez, M.C. Corporate social responsibility reporting and corporate governance mechanisms: An international outlook from emerging countries. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2020, 3, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.; Rigoni, U.; Orij, R.P. Corporate governance and sustainability performance: Analysis of triple bottom line performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, M.A.; Muhammad, S. The impact of board characteristics on corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from nigerian food product firms. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Bus. Adm. 2015, 1, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, E.C.M.; Courtenay, S.M. Board composition, regulatory regime and voluntary disclosure. Int. J. Account. 2006, 41, 262–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Hossain, M.; Adams, M.B. The effects of board composition and board size on the informativeness of annual accounting earnings. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2006, 14, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petra, S.T. Do outside independent directors strengthen corporate boards? Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2005, 5, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, A.; Devi, S.S. The impact of government and foreign affiliate influence on corporate social reporting: The case of malaysia. Manag. Audit. J. 2008, 23, 386–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, N.A.M. Ownership structure and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Some malaysian evidence. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2007, 7, 251–266. [Google Scholar]

- Othman, S.; Darus, F.; Arshad, R. The influence of coercive isomorphism on corporate social responsibility reporting and reputation. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darus, F.; Yusoff, H.; Mohamed, N.; Nejati, M. Do governance structure and financial performance matter in csr reporting. Int. J. Econ. Manag. 2016, 10, 267–284. [Google Scholar]

- Wahyuningrum, I.F.S.; Amal, M.I.; Sularsih, S. The effect of environmental disclosure and performance on profitability in the companies listed on the stock exchange of thailand (set). J. Ilmu Lingkung. 2021, 19, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuningrum, I.F.S.; Oktavilia, S.; Putri, N.; Solikhah, B.; Djajadikerta, H.; Tjahjaningsih, E. Company financial performance, company characteristics, and environmental disclosure: Evidence from singapore. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 623, 12065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logsdon, J.M. Organizational responses to environmental issues: Oil refining companies and air pollution. Res. Corp. Soc. Perform. Policy 1985, 7, 47–71. [Google Scholar]

- Nagendrakumar, N.; Alwis, K.N.N.; Eshani, U.A.K.; Kaushalya, S.B.U. The impact of sustainability practices on the going concern of the travel and tourism industry: Evidence from developed and developing countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 17046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Abeysekera, I. Stakeholders power, corporate characteristics and social and environmental disclosure: Evidence from china. Clean. Prod. 2014, 64, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hackston, D.; Milne, M.J. Some determinants of social and environmental disclosures in new zealand companies. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1996, 9, 77–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamerschlag, R.; Möller, K.; Verbeeten, F. Determinants of voluntary csr disclosure: Empirical evidence from germany. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2011, 5, 233–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuo, L.; Yeh, C.C.; Yu, H.C. Disclosure of corporate social responsibility and environmental management: Evidence from china. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2012, 19, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahouel, B.B.; Peretti, J.-M.; Autissier, D. Stakeholder power and corporate social performance: The ownership effect. Corp. Gov. 2014, 14, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverte, C. Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure ratings by spanish listed firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Pavelin, S. Factors influencing the quality of corporate environmental disclosure. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, L.; Yu, H.-C.; Chang, B.-G. The signals of green governance on mitigation of climate change–evidence from chinese firms. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2015, 7, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.-C. Creating environmental sustainability: Determining factors of water resources information disclosure among chinese enterprises. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2022, 13, 438–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuningrum, I.F.S.; Oktavilia, S.; Setyadharma, A.; Hidayah, R.; Lina, M. Does carbon emissions disclosure affect indonesian companies? IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1108, 012060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuskiya, M.N.F.; Ekanayake, A.; Beddewela, E.; Gerged, A.M. Determinants of corporate environmental disclosures in sri lanka: The role of corporate governance. J. Account. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 11, 367–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Song, L.; Yao, S. The determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from china. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2013, 29, 1833–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.B.; Iyer, E.S.; Kashyap, R.K. Corporate environmentalism: Antecedents and influence of industry type. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, I.E.; Tsalis, T.A. Development of a sustainable balanced scorecard framework. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 34, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trencansky, D.; Tsaparlidis, D. The Effects of Company’s Age, Size and Type of Industry on the Level of CSR: The Development of a New Scale for Measurement of the Level of CSR. Master Thesis, Umeå School of Business and Economics, Umeå, Sweden, 2014; p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Giannarakis, G. The determinants influencing the extent of csr disclosure. Int. J. Law Manag. 2014, 56, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, N.A.; García, S.M. Governance and type of industry as determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosures in latin america. Lat. Am. Bus. Rev. 2020, 21, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandate. Corporate Water Disclosure Guidelines toward a Common Approach to Reporting Water Issues; Pacific Institute: Oakland, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- Uyar, A.; Kuzey, C.; Kilic, M.; Karaman, A.S. Board structure, financial performance, corporate social responsibility performance, csr committee, and ceo duality: Disentangling the connection in healthcare. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1730–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFCASI. International financial corporation advisory service in indonesia. In Indonesia Corporate Governance Manual; IFCASI: Aubervilliers, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Purbawangsa, I.B.A.; Solimun, S.; Fernandes, A.A.R.; Mangesti Rahayu, S. Corporate governance, corporate profitability toward corporate social responsibility disclosure and corporate value (comparative study in indonesia, china and india stock exchange in 2013–2016). Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 16, 983–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulu, C.L. Stakeholder pressure and the quality of sustainability report: Evidence from indonesia. J. Account. Entrep. Financ. Technol. 2020, 2, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Horne, J.C.; Wachowicz, J.M. Fundamentals of Financial Management, 13th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Feijoo, B.; Romero, S.; Ruiz, S. Effect of stakeholders’ pressure on transparency of sustainability reports within the gri framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudyanto, A.; Siregar, S.V. The effect of stakeholder pressure and corporate governance on the sustainability report quality. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2018, 34, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, M.C.; Rodrigues, L.L. Factors influencing social responsibility disclosure by portuguese companies. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 83, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahrani, M.; Soewarno, N. The effect of good corporate governance mechanism and corporate social responsibility on financial performance with earnings management as mediating variable. Asian J. Account. Res. 2018, 3, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nugraheni, P.; Khasanah, E.N. Implementation of the aaoifi index on csr disclosure in indonesian islamic banks. J. Financ. Report. Account. 2019, 17, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazalin, N. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility (csr) disclosure in an emerging economy: Evidence from commercial banks of kazakhstan. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2019, 19, 490–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A. Board independence and corporate social responsibility reporting: Mediating role of stakeholder power. Manag. Res. Rev. 2021, 44, 1217–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, K.; Rui, Z. Revisiting the relationship between corporate governance and corporate social and environmental disclosure practices in pakistan. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 90–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuningrum, I.F.S.; Budihardjo, M.A.; Muhammad, F.I.; Djajadikerta, H.G.; Trireksani, T. Do environmental and financial performances affect environmental disclosures? Evidence from listed companies in indonesia. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 8, 1047–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galani, D.; Gravas, E.; Stavropoulos, A. Company characteristics and environmental policy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2012, 21, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, L.; Yu, H.-C. Corporate political activity and environmental sustainability disclosure: The case of chinese companies. Balt. J. Manag. 2017, 12, 348–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuningrum, I.F.S.; Safitri, L.; Oktavilia, S.; Setyadharma, A. The determinant of environmental disclosure in asean countries. J. Presipitasi Media Komun. Dan Pengemb. Tek. Lingkung. 2022, 19, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.L.; Kung, F.H. Drivers of environmental disclosure and stakeholder expectation: Evidence from taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Anbumozhi, V. Determinant factors of corporate environmental information disclosure: An empirical study of chinese listed companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gamrh, B.; Al-dhamari, R. Firm characteristics and corporate social responsibility disclosure in saudi arabia. Work. Pap. Int. Bussines Manag. 2014, 10, 4283–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswati, E.; Iqbal, S. Do ceo power and industry type affect the csr disclosure? J. Reviu Akunt. Dan Keuang. 2022, 12, 159–170. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Criteria | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Manufacturing companies that are consistently listed on the IDX in 2017–2020 | 193 |

| 2 | Manufacturing companies that do not release standalone or independent sustainability reports | (174) |

| 3 | Manufacturing companies that did not release annual reports between 2017 and 2020 | (0) |

| 4 | Manufacturing companies who, between 2017 and 2020, failed to produce sustainability reports for 4 (four) years in a row | (4) |

| 5 | Companies that lack comprehensive data on the variables used in the study | (0) |

| Total Companies in the Sample | 15 | |

| Research period 2017–2020 | 4 | |

| Total Units of Analysis | 60 |

| Disclosure Items | Indicator |

|---|---|

| Water Withdrawal/Demand | Water source (surface water, underground water, rainwater) |

| Environmental damage from water extraction | |

| Condition of water resources (in the area where the company operates) | |

| Demand for water | |

| Water price, water resource cost | |

| Water source quality and standards | |

| Water Recycling/Reuse and Discharge | Types of wastewaters discharged |

| Rainwater collection and reuse | |

| Wastewater quality and standards | |

| Environmental damage from wastewater recycling | |

| Water recycling, water recycling efficiency | |

| Wastewater discharge (relative/absolute) | |

| Waste fees and waste limits | |

| Water Use | Water use |

| Water consumption (relative/absolute) | |

| Saving Water | Cleanliness, efficient products, and services |

| Water use efficiency | |

| Water saving/reduction (relative/absolute) | |

| Effective utilization of water investment | |

| Spend money on water conservation and wastewater treatment. | |

| Water Management | Plans, goals, or tactics for managing water |

| Special environmental department/responsibility system | |

| Describing the current situation and contemporary issues with the management of water resources | |

| Providing fully functional and safe water, environmental, and sanitation (WASH) services to all employees | |

| Water management requires strategic collaboration with other parties | |

| Water chain supply traced | |

| Communication with stakeholders regarding water issues | |

| Water Policy | Using the GRI Sustainability Reporting Guidelines |

| Actively responding to government environmental protection requirements | |

| Compliance statement for international environmental rules and regulations | |

| Access to financial incentives, including environmental subsidies | |

| Water Risks/Opportunities | Water risk (physical risk, reputation, oversight, and litigation) |

| Water-related penalties, solutions | |

| During the reporting period, there were no major water pollution accidents | |

| Related to water opportunities | |

| Water Data Reliability | Third-party validation of water resource data |

| Quantitative indicator measurement method |

| Variable/ Symbol | Operational Definition | Measurements |

|---|---|---|

| Water Information Disclosure/ WATER | Data collection on the current state of a company’s water management is followed by an analysis of the information’s potential business impacts, the development of tactical solutions, and finally the disclosure of the information to stakeholders [68]. | Content analysis of 37 indicators. The scores given include: 0 = does not reveal anything related to water. 1 = minimum coverage; general terms and brief explanations. 2 = a detailed explanation; the effects of the company or its policies. 3 = quantitative explanation; environmental effects are described in monetary or quantitative terms. 4 = excellent and refers to best practice. |

| CSR Committee/ KOM_CSR | A corporate social responsibility (CSR) committee manages sustainability-related risks and opportunities, advances business objectives, and upholds stakeholder commitments [33]. | A score of 1 for companies with CSR committees and a score of 0 for companies without committees [69]. |

| Independent Board/IND_DEWAN | The corporate oversight body is an independent board that has no connections to the organization outside its oversight role [70]. | Proportion/number of independent commissioners a company has [71]. |

| Government Ownership/ GOV | The government, as a regulator, has great authority to suppress and influence the company’s operational activities [72]. | For companies that are state-owned companies (BUMN), a score of 1, and a score of 0 for companies that are not BUMN [72]. |

| Profitability/PROFIT | The capacity of a business to make profits over a predetermined time [73]. | [69]. |

| Company Size/SIZE | Firm size is a measure of a company’s size (large or small) [60]. | Natural logarithm of total assets [60]. |

| Industry Type/TYPE | Industry type is the classification of a company related to its line of business, business risk, with employees, and a corporate environment [66,67]. | A score of 1 for the following industries:

|

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WATER | 60 | 0.06757 | 0.58108 | 0.2923423 | 0.11102399 |

| KOM_CSR | 60 | 0.00000 | 1.00000 | 0.0833333 | 0.27871781 |

| IND_DEWAN | 60 | 1.00000 | 5.00000 | 2.5166667 | 0.87317202 |

| GOV | 60 | 0.00000 | 1.00000 | 0.1333333 | 0.34280333 |

| PROFIT | 60 | −0.45086 | 0.52670 | 0.0798125 | 0.14534886 |

| SIZE | 60 | 28.55133 | 33.49453 | 30.8272108 | 1.03967087 |

| TYPE | 60 | 0.00000 | 1.00000 | 0.8666667 | 0.34280333 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 60 |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | −0.079 | 0.615 | −0.129 | 0.898 | |

| KOM_CSR | −0.145 | 0.045 | −0.364 | −3.245 | 0.002 | |

| IND_DEWAN | −0.014 | 0.022 | −0.108 | −0.635 | 0.528 | |

| GOV | 0.118 | 0.038 | 0.364 | 3.129 | 0.003 | |

| PROFIT | −0.052 | 0.106 | −0.068 | −0.491 | 0.625 | |

| SIZE | 0.012 | 0.018 | 0.115 | 0.701 | 0.486 | |

| TYPE | 0.031 | 0.064 | 0.096 | 0.488 | 0.627 | |

| Dependent Variable: WATER. | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wahyuningrum, I.F.S.; Chegenizadeh, A.; Hajawiyah, A.; Sriningsih, S.; Utami, S.; Budihardjo, M.A.; Nikraz, H. Determinants of Corporate Water Disclosure in Indonesia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11107. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411107

Wahyuningrum IFS, Chegenizadeh A, Hajawiyah A, Sriningsih S, Utami S, Budihardjo MA, Nikraz H. Determinants of Corporate Water Disclosure in Indonesia. Sustainability. 2023; 15(14):11107. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411107

Chicago/Turabian StyleWahyuningrum, Indah Fajarini Sri, Amin Chegenizadeh, Ain Hajawiyah, Sriningsih Sriningsih, Sri Utami, Mochamad Arief Budihardjo, and Hamid Nikraz. 2023. "Determinants of Corporate Water Disclosure in Indonesia" Sustainability 15, no. 14: 11107. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411107