Studying the Joint Effects of Perceived Service Quality, Perceived Benefits, and Environmental Concerns in Sustainable Travel Behavior: Extending the TPB

Abstract

:1. Introduction

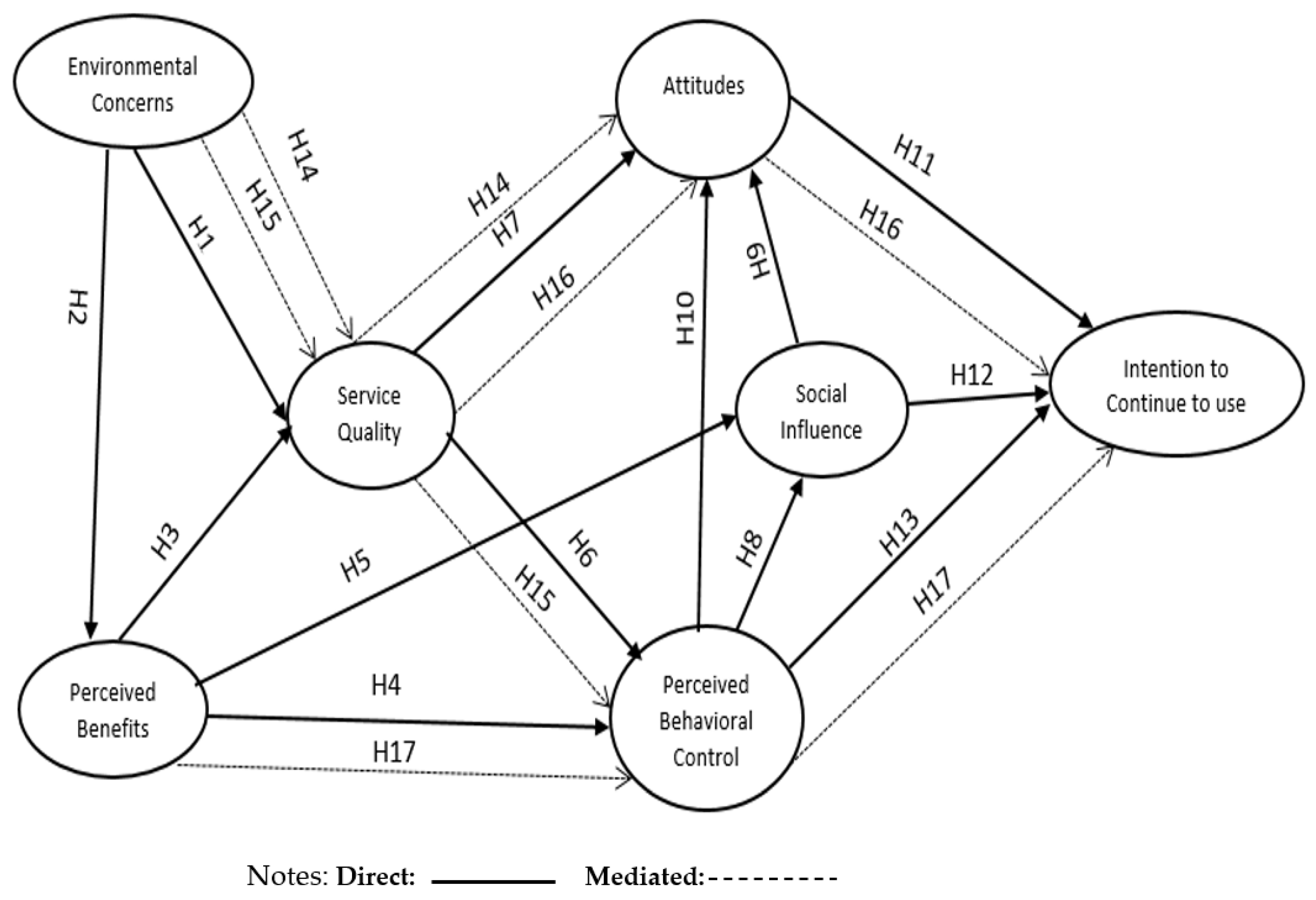

2. Theory and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Relationships between Environmental Concern and Service Quality and Perceived Benefits

2.2. Relationships between Perceived Benefits, Service Quality, Perceived Behavioral Control, and Social Influence

2.3. Relationships among Service Quality, Perceived Behavioral Control, and Attitudes

2.4. Relationships between Perceived Behavioral Control and Social Influence

2.5. Relationships between Social Influence, Perceived Behavioral, and Attitude

2.6. Relationships between Attitudes, Social Influence, Perceived Behavioral Control, and Intention to Continue to Use Behavior

2.7. Mediating Role of Service Quality

2.8. Mediating Role of Attitudes and Perceived Behavioral Control

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

3.2. Measurements

3.3. Statistical Analysis Techniques

4. Results

4.1. Sampling Profile

4.2. Measurement Model Analysis

4.3. Structural Model Analysis

Analysis of the Mediation Effects

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Managerial Contributions

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Agenda

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbasi, G.A.; Kumaravelu, J.; Goh, Y.-N.; Singh, K.S.D. Understanding the Intention to Revisit A Destination by Expanding the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Tpb). Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2021, 25, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L.; Gifford, R.; Vlek, C. Factors Influencing Car Use for Commuting and the Intention to Reduce It: A Question of Self-Interest Or Morality? Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a Theory of Planned Behavior Questionnaire. Amherst, MA, USA, 2006. Available online: http://www.people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. A Bayesian Analysis of Attribution Processes. Psychol. Bull. 1975, 82, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Gelaidan, H.M.; Shah, S.H.A.; Amjad, R. Green Transformational Leadership and Green Creativity? The Mediating Role of Green Thinking and Green Organizational Identity in SMEs. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 977998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hakimi, M.A.; Al-Swidi, A.K.; Gelaidan, H.M.; Mohammed, A. The Influence of Green Manufacturing Practices on the Corporate Sustainable Performance of Smes under the Effect of Green Organizational Culture: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 376, 134346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Swidi, A.K.; Gelaidan, H.M.; Saleh, R.M. The Joint Impact of Green Human Resource Management, Leadership and Organizational Culture on Employees’ Green Behaviour and Organisational Environmental Performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, 128112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandris, K.; Dimitriadis, N.; Markata, D. Can Perceptions of Service Quality Predict Behavioral intentions? An Exploratory Study in the Hotel Sector in Greece. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2002, 12, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azjen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderjahn, I. Personality Variables and Environmental Attitudes as Predictors of Ecologically Responsible Consumption Patterns. J. Bus. Res. 1988, 17, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S. How Does Environmental Concern Influence Specific Environmentally Related Behaviors? A New Answer to An Old Question. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Choice of Travel Mode in the Theory of Planned Behavior: The Roles of Past Behavior, Habit, and Reasoned Action. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 25, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyaya, V.; Bandyopadhyaya, R. Understanding Public Transport Use Intention Post COVID-19 Outbreak Using Modified Theory of Planned Behavior: Case Study from Developing Country Perspective. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2022, 10, 2044–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, H.S.; Taylor, S.F. The Service Provider Switching Model (SPSM): A Model of Consumer Switching Behavior in the Services Industry. J. Serv. Res. 1999, 2, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, D.W.; Higgins, C.; Thompson, R. The Partial Least Squares (Pls) Approach to Casual Modeling: Personal Computer Adoption Ans Use as An Illustration. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Belwal, R.; Belwal, S. Public Transportation Services in Oman: A Study of Public Perceptions. J. Public Transp. 2010, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Chou, C.-P. Practical Issues in Structural Modeling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1987, 16, 78–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndt, A.; Brink, A. Customer Relationship Management and Customer Service; Juta and Company Ltd.: Cape Town, South Africa, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagat-Conway, M.W.; Mirtich, L.; Salon, D.; Harness, N.; Consalvo, A.; Hong, S. Subjective Variables in Travel Behavior Models: A Critical Review and Standardized Transport Attitude Measurement Protocol (Stamp). Transportation 2022, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and Content Analysis of Oral and Written Materials. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology: Methodology; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. In Testing Structural Equation Models; Bollen, K.A., Long, J.S., Eds.; SAGE Publishing: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Capstick, S.; Lorenzoni, I.; Corner, A.; Whitmarsh, L. Prospects for Radical Emissions Reduction Through Behavior and Lifestyle Change. Carbon Manag. 2014, 5, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, R.; Patrício, L.; Jorge, R.N.; Magee, C. Understanding the Travel Experience and Its Impact on Attitudes, Emotions and Loyalty towards the Transportation Provider–A Quantitative Study With Mid-Distance Bus Trips. Transp. Policy 2014, 31, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascetta, E.; Cartenì, A. A Quality-Based Approach to Public Transportation Planning: Theory and A Case Study. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2014, 8, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, P.Y.K.; Hu, P.J.-H. Information Technology Acceptance by Individual Professionals: A Model Comparison Approach. Decis. Sci. 2001, 32, 699–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.; Bisai, S. Factors Influencing Green Purchase Behavior of Millennials in India. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2018, 29, 798–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Cao, C.; Fang, X.; Kang, Z. Expanding the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Reveal Urban Residents’ Pro-Environment Travel Behaviour. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-M.; Wu, H.C. How Do Environmental Knowledge, Environmental Sensitivity, and Place Attachment Affect Environmentally Responsible Behavior? An Integrated Approach for Sustainable Island Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.F.Y.; To, W.M. An Extended Model of Value-Attitude-Behavior to Explain Chinese Consumers’ Green Purchase Behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and Opinion on Structural Equation Modeling. Jstor 1998, 22, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Gopal, A.; Salisbury, W.D. Advancing the Theory of Adaptive Structuration: The Development of A Scale to Measure Faithfulness of Appropriation. Inf. Syst. Res. 1997, 8, 342–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.-T.H.; Lee, W.-I.; Chen, T.-H. Environmentally Responsible Behavior in Ecotourism: Antecedents and Implications. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemes, M.D.; Gan, C.; Ren, M. Synthesizing the Effects of Service Quality, Value, and Customer Satisfaction on Behavioral Intentions in the Motel Industry: An Empirical Analysis. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2011, 35, 530–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çoban, M. Investigation of the Relationship Between Higher Education Students’ Service Quality Perceptions, Attitudes, and Self-Efficacy towards Distance Education. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compeau, D.; Higgins, C.A.; Huff, S. Social Cognitive Theory and Individual Reactions to Computing Technology: A Longitudinal Study. Mis Q. 1999, 23, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J., Jr.; Brady, M.K.; Hult, G.T.M. Assessing the Effects of Quality, Value, and Customer Satisfaction on Consumer Behavioral Intentions in Service Environments. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagger, T.S.; Sweeney, J.C.; Johnson, L.W. A Hierarchical Model of Health Service Quality: Scale Development and Investigation of An Integrated Model. J. Serv. Res. 2007, 10, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Li, R.; Liu, Z.; Lin, S. Impacts of the Introduction of Autonomous Taxi on Travel Behaviors of the Experienced User: Evidence from A One-Year Paid Taxi Service in Guangzhou, China. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 130, 103311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the Theory of Planned Behavior to Identify Key Beliefs Underlying Pro-Environmental Behavior in High-School Students: Implications for Educational interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepa, L.; Mondal, A.; Raman, A.; Pinjari, A.R.; Bhat, C.R.; Srinivasan, K.K.; Pendyala, R.M.; Ramadurai, G. An Analysis of Individuals’ Usage of Bus Transit in Bengaluru, India: Disentangling the influence of Unfamiliarity With Transit from That of Subjective Perceptions of Service Quality. Travel Behav. Soc. 2022, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’olio, L.; Ibeas, A.; Cecin, P. the Quality of Service Desired by Public Transport Users. Transp. Policy 2011, 18, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devika, R.; Harikrishna, M. Analysis of Factors Influencing Mode Shift to Public Transit in a Developing Country. In Iop Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Modeling and Simulation In Civil Engineering, Kerala, India, 11–13 December 2019; Iop Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 491, p. 012054. [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Sinkovics, R.R.; Bohlen, G.M. Can Socio-Demographics Still Play A Role in Profiling Green Consumers? A Review of the Evidence and An Empirical Investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, I.J.; Cooper, S.R.; Conchie, S.M. An Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour Model of the Psychological Factors Affecting Commuters’ Transport Mode Use. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorce, L.C.; da Silva, M.C.; Mauad, J.R.C.; de Faria Domingues, C.H.; Borges, J.A.R. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Consumer Purchase Behavior for Organic Vegetables in Brazil: The Role of Perceived Health Benefits, Perceived Sustainability Benefits and Perceived Price. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 91, 104191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Liere, K.D. Commitment to the Dominant Social Paradigm and Concern for Environmental Quality. Soc. Sci. Q. 1984, 65, 1013. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Mertig, A.G. Global Environmental Concern: An Anomaly for Postmaterialism. Soc. Sci. Q. 1997, 78, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D. The “New Environmental Paradigm”. J. Environ. Educ. 1978, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.; Catton, W.R.; Howell, R.E. Measuring Endorsement of an Ecological Worldview: A Revised Nep Scale. In Proceedings of the Meeting of the Rural Sociological Society, State College, PA, USA, 16–19 August 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Egset, K.S.; Nordfjærn, T. The Role of Transport Priorities, Transport Attitudes and Situational Factors for Sustainable Transport Mode Use in Wintertime. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 62, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elie-Dit-Cosaque, C.; Pallud, J.; Kalika, M. The Influence of Individual, Contextual, and Social Factors on Perceived Behavioral Control of Information Technology: A Field theory Approach. J. Manag. inf. Syst. 2011, 28, 201–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L.; Forward, S.E. Is the Intention to Travel in A Pro-Environmental Manner and the Intention to Use the Car Determined by Different Factors? Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2011, 16, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L.; Garvill, J.; Nordlund, A.M. Acceptability of Single and Combined Transport Policy Measures: The Importance of Environmental and Policy Specific Beliefs. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2008, 42, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models With Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransson, N.; Gärling, T. Environmental Concern: Conceptual Definitions, Measurement Methods, and Research Findings. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X. A Novel Perspective to Enhance the Role of Tpb in Predicting Green Travel: The Moderation of Affective-Cognitive Congruence of Attitudes. Transportation 2021, 48, 3013–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C.M.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common Methods Variance Detection in Business Research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, R.; Sipe, N. Light Rail Transit (Lrt) and Transit Villages in Qatar: A Planning-Strategy to Revitalize the Built Environment of Doha. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2017, 10, 379–399. [Google Scholar]

- Gansser, O.A.; Reich, C.S. Influence of the New Ecological Paradigm (Nep) and Environmental Concerns on Pro-Environmental Behavioral Intention Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (Tpb). J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 382, 134629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B. Modelling Motivation and Habit in Stable Travel Mode Contexts. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B.; Abraham, C. Psychological Correlates of Car Use: A Meta-Analysis. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2008, 11, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelaidan, H.M.; Mabkhot, H.A.; Al-Kwifi, O.S. The Mediation Role of Brand Trust and Satisfaction Between Brand Image and Loyalty. J. Glob. Bus. Adv. 2021, 14, 845–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, J.D.; Redi, A.A.N.P.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Persada, S.F.; Ong, A.K.S.; Young, M.N.; Nadlifatin, R. Choosing A Package Carrier During COVID-19 Pandemic: An Integration of Pro-Environmental Planned Behavior (Pepb) Theory and Service Quality (Servqual). J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 346, 131123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H. The Norm Activation Model and Theory-Broadening: Individuals’ Decision-Making on Environmentally-Responsible Convention Attendance. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Travelers’ Pro-Environmental Behavior in A Green Lodging Context: Converging Value-Belief-Norm Theory and the Theory of Planned Behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yoon, H.J. Hotel Customers’ Environmentally Responsible Behavioral Intention: Impact of Key Constructs on Decision in Green Consumerism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 45, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, G.; Weiss, M. Co2 Labelling of Passenger Cars in Europe: Status, Challenges, and Future Prospects. Energy Policy 2016, 95, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. Consumer Attitude and Purchase intention toward Green Energy Brands: The Roles of Psychological Benefits and Environmental Concern. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Preacher, K.J. Statistical Mediation Analysis With A Multicategorical Independent Variable. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2014, 67, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, Y.; Gifford, R. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior: Predicting the Use of Public Transportation. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 2154–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkanen, P.; Verplanken, B.; Olsen, S.O. Ethical Values and Motives Driving Organic Food Choice. J. Consum. Behav. Int. Res. Rev. 2006, 5, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Liang, L.J.; Meng, B.; Choi, H.C. The Role of Perceived Quality on High-Speed Railway Tourists’ Behavioral Intention: An Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.-H.; Yang, C. Predicting the Travel Intention to Take High Speed Rail Among College Students. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2010, 13, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.-W.; Chang, C.-W.; Ma, Y.-C. A New Reality: Exploring Continuance Intention to Use Mobile Augmented Reality for Entertainment Purposes. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irawan, M.Z.; Belgiawan, P.F.; Joewono, T.B. Investigating the Effects of Individual Attitudes and Social Norms on Students’ Intention to Use Motorcycles–An Integrated Choice and Latent Variable Model. Travel Behav. Soc. 2022, 28, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.L. Revisiting Sample Size and Number of Parameter Estimates: Some Support for the N: Q Hypothesis. Struct. Equ. Model. 2003, 10, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, D.; Kant, R. Green Purchasing Behaviour: A Conceptual Framework and Empirical Investigation of Indian Consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.Y.; Chung, J.Y.; Kim, Y.G. Effects of Environmentally Friendly Perceptions on Customers’ Intentions to Visit Environmentally Friendly Restaurants: An Extended theory of Planned Behavior. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 20, 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Pauleit, S.; Naumann, S.; Davis, M.; Artmann, M.; Haase, D.; Knapp, S.; Korn, H.; Stadler, J.; et al. Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in Urban Areas: Perspectives on Indicators, Knowledge Gaps, Barriers, and Opportunities for Action. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, J.L. Driving to Save Time Or Saving Time to Drive? The Enduring Appeal of the Private Car. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2014, 65, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Schmöcker, J.-D.; Yu, J.W.; Choi, J.Y. Service Quality Evaluation for Urban Rail Transfer Facilities with Rasch Analysis. Travel Behav. Soc. 2018, 13, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-K.; Oh, J.; Park, J.-H.; Joo, C. Perceived Value and Adoption Intention for Electric Vehicles in Korea: Moderating Effects of Environmental Traits and Government Supports. Energy 2018, 159, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-J.; Hall, C.M. Can Climate Change Awareness Predict Pro-Environmental Practices in Restaurants? Comparing High and Low Dining Expenditure. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Han, H. Intention to Pay Conventional-Hotel Prices At A Green Hotel–A Modification of the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Klöckner, C.A.; Blöbaum, A. A Comprehensive Action Determination Model: Toward A Broader Understanding of Ecological Behaviour Using the Example of Travel Mode Choice. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.-T.; Chen, C.-F. Behavioral Intentions of Public Transit Passengers—The Roles of Service Quality, Perceived Value, Satisfaction and Involvement. Transp. Policy 2011, 18, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting Consumers Who Are Willing to Pay More for Environmentally Friendly Products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior: Factors Fostering Millennials’ Intention to Purchase Eco-Sustainable Products in An Emerging Market. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2022, 65, 1507–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Sung, H.J.; Jeon, H.M. Determinants of Continuous Intention on Food Delivery Apps: Extending Utaut2 With Information Quality. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, M. Tourists’ Pro-Environmental Behaviour in Travel Destinations: Benchmarking the Power of Social Interaction and Individual Attitude. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1371–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shang, H. Service Quality, Perceived Value, and Citizens’ Continuous-Use Intention Regarding E-Government: Empirical Evidence from China. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cui, W.; Zhou, R.; Chan, A.H. The Effects of Social Conformity and Gender on Drivers’ Behavioural Intention towards Level-3 Automated Vehicles. Travel Behav. Soc. 2022, 29, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, H.; Li, Y.; Amin, A. Factors Influencing Chinese Residents’ Post-Pandemic Outbound Travel Intentions: An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model Based on the Perception of COVID-19. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 871–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizin, S.; Van Dael, M.; Van Passel, S. Battery Pack Recycling: Behaviour Change Interventions Derived from An Integrative Theory of Planned Behaviour Study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 122, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.H.; Van Breukelen, G.J.; Peters, G.-J.Y.; Kok, G. Commuting Travel Mode Choice Among Office Workers: Comparing An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model Between Regions and Organizational Sectors. Travel Behav. Soc. 2016, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabry, R. Urbanisation and Physical Activity in the Gcc: A Case Study of Oman. In LSE Middle East Centre Paper Series; Kuwait Programme LSE Middle East Centre: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mambu, E. The Influence of Brand Image, and Service Quality toward Consumer Purchase intention of Blue Bird Taxi Manado. J. Emba J. Ris. Ekon. Manaj. Bisnis Dan Akunt. 2015, 3, 645–653. [Google Scholar]

- Manaktola, K.; Jauhari, V. Exploring Consumer Attitude and Behaviour Towards Green Practices in the Lodging Industry in India. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 19, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, S. Expected Service Quality Measurement in Tourism Higher Education. Nase Gospod. NG 2006, 52, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelidou, N.; Hassan, L.M. The Role of Health Consciousness, Food Safety Concern and Ethical Identity on Attitudes and Intentions towards Organic Food. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogaji, E.; Erkan, I. Insight into Consumer Experience on Uk Train Transportation Services. Travel Behav. Soc. 2019, 14, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouwen, A. Drivers of Customer Satisfaction With Public Transport Services. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2015, 78, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuburger, L.; Egger, R. Travel Risk Perception and Travel Behaviour During the COVID-19 Pandemic 2020: A Case Study of the Dach Region. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzl, C.; Roldan, J.L.; Cepeda, G. Mediation Analysis in Partial Least Squares Path Modeling: Helping Researchers Discuss More Sophisticated Models. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1849–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlund, A.M.; Garvill, J. Value Structures Behind Proenvironmental Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlund, A.M.; Garvill, J. Effects of Values, Problem Awareness, and Personal Norm on Willingness to Reduce Personal Car Use. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Kim, K. Customer Satisfaction, Service Quality, and Customer Value: Years 2000–2015. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Management 2017, 29, 2–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and Its Implications for Future Research. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, Y.; Gal-Tzur, A.; Rechavi, A. Identifying Attributes of Public Transport Services for Urban Tourists: A Data-Mining Method. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 93, 103069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.M.; Brown, G.; Robinson, G.M. The Influence of Place Attachment, and Moral and Normative Concerns on the Conservation of Native Vegetation: A Test of Two Behavioural Models. J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, X.; Wang, S.; Chen, Q.; Yan, S. Exploring the Interaction Effects of Norms and Attitudes on Green Travel Intention: An Empirical Study in Eastern China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1317–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, X.; Wang, S.; Yan, S. Exploring the Effects of Normative Factors and Perceived Behavioral Control on Individual’s Energy-Saving Intention: An Empirical Study in Eastern China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 134, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Thiele, K.O.; Gudergan, S.P. Estimation Issues With Pls and Cbsem: Where the Bias Lies! J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3998–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Howard, J.A. Internalized Values as Motivators of Altruism. In Development and Maintenance of Prosocial Behavior; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.; Wang, S.; Zhao, D. Exploring Urban Resident’s Vehicular PM2.5 Reduction Behavior Intention: An Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, M.; Jo, H.S. What Quality Factors Matter in Enhancing the Perceived Benefits of Online Health Information Sites? Application of the Updated Delone and Mclean Information Systems Success Model. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2020, 137, 104093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarin, F.; Olsson, L.E.; Friman, M.; Wästlund, E. Importance of Motives, Self-Efficacy, Social Support and Satisfaction with Travel for Behavior Change During Travel Intervention Programs. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 62, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.R.; Louis, W.R.; Terry, D.J.; Greenaway, K.H.; Clarke, M.R.; Cheng, X. Congruent Or Conflicted? The Impact of Injunctive and Descriptive Norms on Environmental Intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreen, N.; Purbey, S.; Sadarangani, P. Impact of Culture, Behavior and Gender on Green Purchase Intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New Environmental Theories: Toward A Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sujood; Hamid, S.; Bano, N. Behavioral Intention of Traveling in the Period of COVID-19: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior (Tpb) and Perceived Risk. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2022, 8, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, P.L.; Hsiao, T.Y.; Huang, L.; Morrison, A.M. The Influence of Green Trust on Travel Agency Intentions to Promote Low-Carbon tours for the Purpose of Sustainable Development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1185–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Transport-Related Lifestyle and Environmentally-Friendly Travel Mode Choices: A Multi-Level Approach. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 107, 166–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripp, C.; Drea, J.T. Selecting and Promoting Service Encounter Elements in Passenger Rail Transportation. J. Serv. Mark. 2002, 16, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, R.H.; Patel, J.D.; Acharya, N. Causality Analysis of Media influence on Environmental Attitude, Intention and Behaviors Leading to Green Purchasing. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuveri, G.; Sottile, E.; Piras, F.; Meloni, I. A Panel Data Analysis of Tour-Based University Students’ Travel Behaviour. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2020, 8, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzir, M.U.H.; Al Halbusi, H.; Thurasamy, R.; Hock, R.L.T.; Aljaberi, M.A.; Hasan, N.; Hamid, M. the Effects of Service Quality, Perceived Value and Trust in Home Delivery Service Personnel on Customer Satisfaction: Evidence from A Developing Country. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology Acceptance Model 3 and A Research Agenda on Interventions. Decis. Sci. 2008, 39, 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward A Unified View. Mis Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. Mis Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobeva, D.; Scott, I.J.; Oliveira, T.; Neto, M. Adoption of New Household Waste Management Technologies: The Role of Financial Incentives and Pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, J.; Zhao, D. the Impact of Policy Measures on Consumer Intention to Adopt Electric Vehicles: Evidence from China. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 105, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liao, H.; Wang, J.-W.; Chen, T. the Role of Environmental Concern in the Public Acceptance of Autonomous Electric Vehicles: A Survey from China. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 60, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, S.-S.; Guan, X.; Chiang, T.-Y.; Ho, J.-L.; Huan, T.-C.T.C. Reinterpreting the Theory of Planned Behavior and Its Application to Green Hotel Consumption Intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaina, S.; Zaina, S.; Furlan, R. Urban Planning in Qatar: Strategies and Vision for the Development of Transit Villages in Doha. Aust. Plan. 2016, 53, 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The Behavioral Consequences of Service Quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Jin, H.; Gang, X.; Kang, Z.; Luan, J. County Economy, Population, Construction Land, and Carbon Intensity in A Shrinkage Scenario. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetu, D.; Miller, L. Managing Customer Loyalty in the Auto Industry. 2010. Available online: http://www.Martinmeister.Cl/Wp (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Zhang, T.; Tao, D.; Qu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, H. Automated Vehicle Acceptance in China: Social Influence and Initial Trust Are Key Determinants. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 112, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, F.; Wang, K. Destination Service Encounter Modeling and Relationships with Tourist Satisfaction. Sustainability 2019, 11, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 403 | 30.2 |

| Male | 931 | 69.8 | |

| Age | Less than or equal 25 | 778 | 58.3 |

| More than 25 | 556 | 41.7 | |

| Car Ownership | Have a car | 898 | 67.3 |

| Don’t have a car | 436 | 32.7 | |

| Education | Secondary | 331 | 24.8 |

| Diploma | 207 | 15.5 | |

| Bachelor | 679 | 50.9 | |

| Postgraduate | 117 | 8.8 | |

| Income | Less than 10,000 | 744 | 55.8 |

| More than 10,000 | 590 | 44.2 | |

| Travel Purpose | Work | 354 | 26.5 |

| Study | 472 | 35.4 | |

| Social | 147 | 11.0 | |

| Pleasure | 361 | 27.1 | |

| Total | 1334 | 100.0 |

| Construct | Items | Factor Loadings | Composite Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service Quality | SQ1 | 0.706 | 0.911 | 0.594 |

| SQ4 | 0.818 | |||

| SQ5 | 0.789 | |||

| SQ6 | 0.780 | |||

| SQ7 | 0.803 | |||

| SQ8 | 0.745 | |||

| SQ9 | 0.746 | |||

| Environmental concerns | EC4 | 0.722 | 0.836 | 0.561 |

| EC3 | 0.763 | |||

| EC2 | 0.797 | |||

| EC1 | 0.711 | |||

| Perceived benefits | PB6 | 0.864 | 0.881 | 0.787 |

| PB5 | 0.910 | |||

| PB4 | 0.837 | |||

| PB3 | 0.857 | |||

| PB2 | 0.787 | |||

| Social influence | SN1 | 0.904 | 0.930 | 0.815 |

| SN2 | 0.934 | |||

| SN3 | 0.870 | |||

| Attitude | AT1 | 0.777 | 0.844 | 0.643 |

| AT2 | 0.842 | |||

| AT3 | 0.785 | |||

| Perceived behavioral control | PBC3 | 0.762 | 0.854 | 0.662 |

| PBC2 | 0.832 | |||

| PBC1 | 0.844 | |||

| Intention to continue to use the metro | CI2 | 0.910 | 0.900 | 0.750 |

| CI3 | 0.868 | |||

| CI4 | 0.817 |

| Construct | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) IC | 0.866 | ||||||

| (2) SQ | 0.386 | 0.770 | |||||

| (3) EC | 0.194 | 0.532 | 0.749 | ||||

| (4) SN | 0.756 | 0.330 | 0.124 | 0.903 | |||

| (5) AT | 0.810 | 0.419 | 0.184 | 0.765 | 0.802 | ||

| (6) PBC | 0.755 | 0.393 | 0.222 | 0.751 | 0.764 | 0.813 | |

| (7) PB | 0.282 | 0.590 | 0.484 | 0.311 | 0.331 | 0.384 | 0.852 |

| Hyp. No. | Hypothesis | Standardized Path Coefficient | Standard Error | t-Value | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | EC ---> SQ | 0.30 | 0.03 | 9.944 | 0.000 | confirmed |

| H2 | EC ---> PB | 0.708 | 0.047 | 11.118 | 0.000 | confirmed |

| H3 | PB ---> SQ | 0.280 | 0.02 | 13.966 | 0.000 | confirmed |

| H4 | PB ---> PBC | 0.196 | 0.032 | 6.118 | 0.000 | confirmed |

| H5 | PB ---> SN | 0.029 | 0.025 | 1.152 | 0.249 | Not confirmed |

| H6 | SQ ---> PBC | 0.367 | 0.051 | 7.173 | 0.000 | confirmed |

| H7 | SQ ---> AT | 0.157 | 0.031 | 11.129 | 0.000 | confirmed |

| H8 | PBC ---> SN | 0.892 | 0.038 | 23.507 | 0.000 | confirmed |

| H9 | SN ---> AT | 0.344 | 0.031 | 5.052 | 0.000 | confirmed |

| H10 | PBC ---> AT | 0.375 | 0.040 | 9.277 | 0.000 | confirmed |

| H11 | AT ---> CI | 0.733 | 0.054 | 13.476 | 0.000 | confirmed |

| H12 | SN ---> CI | 0.107 | 0.031 | 3.455 | 0.000 | confirmed |

| H13 | PBC ---> CI | 0.125 | 0.04 | 3.117 | 0.002 | confirmed |

| Hyp. No. | Hypothesized Relationship | Indirect Path Coefficient (a × b) | Lower Bound 90% CI | Upper Bound 90% CI | Decision | Direct Path Coefficient (c’) | Lower Bound 90% CI | Upper Bound 90% CI | Decision | Mediation Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H14 | EC ---> SQ ---> AT | 0.05 | 0.030 | 0.080 | Significant Indirect Effect | −0.016 | −0.078 | −0.04 | Significant direct Effect | Competitive Partial Mediation |

| H15 | EC ---> SQ ---> PBC | 0.119 | 0.082 | 0.173 | Significant Indirect Effect | −0.071 | −0.168 | 0.016 | Insignificant direct Effect | Full Mediation |

| H16 | SQ --->AT ---> CI | 0.120 | 0.069 | 0.175 | Significant Indirect Effect | 0.057 | −0.001 | 0.119 | Insignificant direct Effect | Full Mediation |

| H17 | PB ---> PBC ---> CI | 0.030 | 0.011 | 0.056 | Significant Indirect Effect | −0.062 | −0.094 | −0.026 | Significant direct Effect | Competitive Partial Mediation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gelaidan, H.M.; Al-Swidi, A.; Hafeez, M.H. Studying the Joint Effects of Perceived Service Quality, Perceived Benefits, and Environmental Concerns in Sustainable Travel Behavior: Extending the TPB. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411266

Gelaidan HM, Al-Swidi A, Hafeez MH. Studying the Joint Effects of Perceived Service Quality, Perceived Benefits, and Environmental Concerns in Sustainable Travel Behavior: Extending the TPB. Sustainability. 2023; 15(14):11266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411266

Chicago/Turabian StyleGelaidan, Hamid Mahmood, Abdullah Al-Swidi, and Muhammad Haroon Hafeez. 2023. "Studying the Joint Effects of Perceived Service Quality, Perceived Benefits, and Environmental Concerns in Sustainable Travel Behavior: Extending the TPB" Sustainability 15, no. 14: 11266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411266