Enterprise Spatial Agglomeration and Economic Growth in Northeast China: Policy Implications for Uneven to Sustainable Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Theoretical Mechanisms and Research Hypotheses

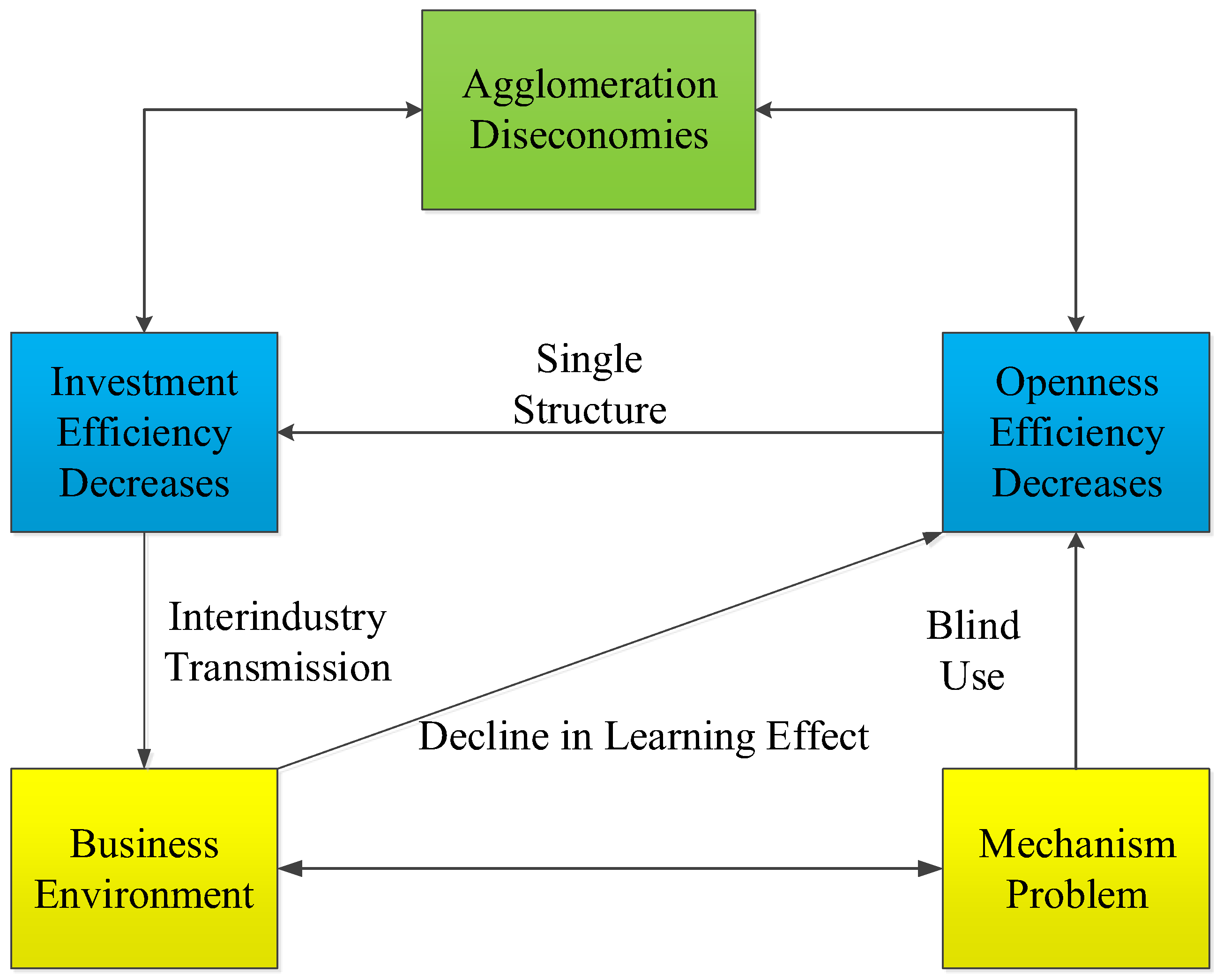

3.1. Conflicting Manifestations of Investment in the Enterprise Agglomeration Process

3.2. Efficiency Release at the Level of Agglomeration and Openness

4. Methodology

4.1. Investigation Area

4.2. Model Setting

4.3. Variable Selection, Data Source, and Processing

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Test of Enterprise Agglomeration Diseconomies

5.2. Regional Comparison

5.3. Mechanism Analysis

5.4. Robustness Test

6. Discussion

6.1. Optimising the Industrial Structure

6.2. Cultivating a Healthy Business Environment

6.3. Promoting Coordinated Development and Mutual Benefit

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siciliano, G.; Crociata, A.; Turvani, M. A Multi-level Integrated Analysis of Socio-economic Systems Metabolism: An Application to the Italian Regional Level. Environ. Policy Gov. 2012, 22, 350–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czudec, A.; Kata, R.; Wosiek, M. Reducing the Development Gaps between Regions in Poland with the Use of European Union Funds. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2019, 25, 447–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, W.; Pan, M.Z.; Wu, J.M.; Chen, T.T.; Li, X. The Patterns and Driving Forces of Uneven Regional Growth in ASEAN Countries: A Tale of Two Thailands’ Path toward Regional Coordinated Development. Growth Change 2021, 52, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.Y.; Teng, F.; Song, J.P. Evaluation of Spatial Balance of China’s Regional Development. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.P.; Cao, X.; Hamm, N.A.S.; Lin, T.; Zhang, G.Q.; Chen, B.H. Unbalanced Development Characteristics and Driving Mechanisms of Regional Urban Spatial Form: A Case Study of Jiangsu Province, China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarin, T. The Concept of Sustainable Development: From its Beginning to the Contemporary Issues. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. 2018, 21, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manioudis, M.; Meramveliotakis, G. Broad Strokes towards a Grand Theory in the Analysis of Sustainable Development: A Return to the Classical Political Economy. New Political Econ. 2022, 27, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Liu, B.L.; Shao, X.F. Spatial Effects of Industrial Synergistic Agglomeration and Regional Green Development Efficiency: Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2022, 112, 106156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, K.; Rizk, R.; Zaki, C. Firm Productivity and Agglomeration Economies: Evidence from Egyptian Data. Appl. Econ. 2019, 51, 5528–5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.P.; Li, C.G.; Zhang, J. Understanding Urban Shrinkage from a Regional Perspective: Case Study of Northeast China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 05020025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Guan, H.M.; Feng, Z.X.; Long, W. Regional Economic Resilience in the Central-Cities and Outer-Suburbs of Northeast China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. China Urban Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z.Q.; Qin, M.; Song, S.F. Re-study on Chinese City Size and Policy Formation. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 60, 101390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.K.; Feng, Z.X.; Li, C.G. How Does Population Shrinkage Affect Economic Resilience? A Case Study of Resource-Based Cities in Northeast China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M. A Theory of City Size. Science 2013, 340, 1418–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, A. Principles of Political Economy, 3rd ed.; Maxmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1890; pp. 40–60. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Economy of Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, S.S.; Strange, W.C. Evidence on the Nature and Sources of Agglomeration Economies. In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics; Henderson, J.V., Thisse, J.F., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 4, pp. 2119–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuermann, D.F.; Schmieder, J.F. The Effect of Infrastructure on Worker Mobility: Evidence from High-speed Rail Expansion in Germany. J. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 19, 335–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.F.; Zheng, S.Q.; Kahn, M.E. The Role of Transportation Speed in Facilitating High Skilled Teamwork. J. Urban Econ. 2020, 115, 103212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.L.; Huang, X.J.; Liu, Y.H.; Luan, X.; Song, Y. The Impact of High-Tech Industry Agglomeration on Green Economy Efficiency—Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.F.; Luo, C.J.; He, S. Does Urban Agglomeration Promote the Development of Cities? An Empirical Analysis Based on Spatial Econometrics. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.H.; Li, X.N.; Lu, Y.D. How Urbanization Economies Impact TFP of R&D Performers: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.M.; Dickinson, R.E.; Tian, Y.H.; Fang, J.Y.; Li, Q.X.; Kaufmann, R.K.; Tucker, C.J.; Myneni, R.B. Evidence for a Significant Urbanization Effect on Climate in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 9540–9544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Ebenstein, A.; Greenstone, M.; Li, H.B. Evidence on the Impact of Sustained Exposure to Air Pollution on Life Expectancy from China’ s Huai River Policy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 12936–12941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdonnell, M.J.; Macgregor-Fors, I. The Ecological Future of Cities. Science 2016, 352, 936–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsley, R.W.; Strange, W.C. Coagglomeration, Clusters, and the Scale and Composition of Cities. J. Polit. Econ. 2014, 122, 1064–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Hua, D.; Li, J. A View of Industrial Agglomeration, Air Pollution and Economic Sustainability from Spatial Econometric Analysis of 273 Cities in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlin, B. Interregional and International Trade; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur, W.B. Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in the Economy; The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, R.E. Agglomeration and Endogenous Capital. Eur. Econ. Rev. 1999, 43, 253–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Helms, W.S.; Li, W. Tapping into Agglomeration Benefits by Engaging in a Community of Practice. Strateg. Organ. 2020, 18, 617–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Kerr, W.R.; Ponzetto, G.A.M. Clusters of Entrepreneurship. J. Urban Econ. 2010, 67, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.Q.; Lu, M. Growth Led by Human Capital in Big Cities: Exploring Complementarities and Spatial Agglomeration of the Workforce with Various Skills. China Econ. Rev. 2019, 57, 101113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.Y.; Pan, Z.C.; Wang, Y.M.; Wei, F. Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of the Success or Failure of China’ s Overseas Arable Land Investment Projects—Based on the Countries along the “Belt and Road”. Land 2022, 11, 2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, K.N.; Zhuang, R.L. Producer Services Agglomeration and Carbon Emission Reduction—An Empirical Test Based on Panel Data from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Xiang, K.H. Great turning: How Has Chinese Economy Been Trapped in an Efficiency-and-balance Tradeoff? Asian Econ. Pap. 2016, 15, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.; Thisse, J.F. Economics of Agglomeration: Cities, Industrial Location, and Globalization, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Trung, N.B.; Kaizoji, T. Investment Climate and Firm Productivity: An Application to Vietnamese Manufacturing Firms. Appl. Econ. 2017, 49, 4394–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Kallal, H.D.; Scheinkman, J.A.; Shlefer, A. Growth in Cities. J. Polit. Econ. 1992, 100, 1126–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. China Marine Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- National Sustainable Development Plan for Resource-Based Cities (2013–2020). Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2013-12/02/content_4549.htm (accessed on 2 December 2013).

- Tirole, J. The Theory of Industrial Organization; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.Z.; Ma, M.X. Firm Size, Economics of Scale and Industrial Clusters. China Ind. Eco. 2004, 6, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widodo, W.; Salim, R.; Bloch, H. The Effects of Agglomeration Economies on Technical Efficiency of Manufacturing Firms: Evidence from Indonesia. Appl. Econ. 2015, 47, 3258–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhang, X.Q.; Huang, C.H. Influence of Population Agglomeration on Urban Economic Resilience in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, F.; Lin, S.X.; Ren, Y. Social Identity and Inequality: The Impact of China’s Hukou System. J. Public Econ. 2015, 123, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Xu, Z.Y.; Yashiro, N. Agglomeration and Productivity in China: Firm Level Evidence. China Econ. Rev. 2015, 33, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, K.X.; Liu, X.T.; Xu, J. Digital Economy and the Sustainable Development of China’s Manufacturing Industry: From the Perspective of Industry Performance and Green Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.; Topel, R. The Social Value of Education and Human Capital. In Handbook of the Economics of Education; Hanushek, E., Welch, F., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 459–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.L.; Ye, B.; Ye, J.L.; Pan, Z.D. Trustworthiness of Local Government, Institutions, and Self-employment in Transitional China. China Econ. Rev. 2019, 57, 101329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.V.; Squires, T.; Storeygard, A.; Weil, D. The Global Spatial Distribution of Economic Activity: Nature, History, and the Role of Trade. Q. J. Econ. 2018, 133, 357–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véganzonès-Varoudakis, M.A.; Nguyen, H.T.M. Investment Climate, Outward Orientation and Manufacturing Firm Productivity: New Empirical Evidence. Appl. Econ. 2018, 50, 5766–5794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazalian, P.L.; Amponsem, F. The Effects of Economic Freedom on FDI Inflows: An Empirical Analysis. Appl. Econ. 2019, 51, 1111–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.J.; Deng, R.C.; Liu, R.X.; Peng, Q. Effects of Special Economic Zones on FDI in Emerging Economies: Does Institutional Quality Matter? Sustainability 2020, 12, 8409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.; Ogawa, H. Multiple Equilibria and Structural Transition of Non-monocentric Urban Configurations. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 1982, 12, 161–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.E. On the Mechanics of Economic Development. J. Monet. Econ. 1988, 22, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L. Learning in Cities. J. Urban Econ. 1999, 46, 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.E.; Rossi-Hansberg, E. On the Internal Structure of Cities. Econometrica 2002, 70, 1445–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.; Mori, T.; Henderson, J.V.; Kanemoto, Y. Spatial Distribution of Economic Activities in Japan and China. In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics; Henderson, J.V., Thisse, J.F., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 4, pp. 2911–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Raza, A.; Sui, H.G. Infrastructure Investment and Economic Growth Quality: Empirical Analysis of China’ s Regional Development. Appl. Econ. 2021, 53, 2615–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Name | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|

| Urban productivity | Nonagricultural GDP/nonagricultural employment | |

| Enterprise density | Number of industrial enterprises over the designated size/built-up area | |

| Urban diversity level | See the body | |

| Level of urban specialization | See the body | |

| Fixed asset investment level | Fixed asset investment/nonfarm employment | |

| Foreign direct investment | Actual level of foreign investment | |

| Human capital | Expenditure on education/number of students | |

| Nonagricultural industry proportion | Proportion of nonagricultural output in municipal GDP | |

| Whether a city is coastal city | Dummy variable; 1 if a coastal city, and 0 otherwise | |

| Whether a city is an administrative center | Dummy variable; 1 if the provincial capital, and 0 otherwise | |

| Whether a city is a resource-based city | Dummy variable; 1 if a resource-based city, and 0 otherwise |

| Variable | 1999–2004 | 2005–2010 | 2011–2015 |

|---|---|---|---|

| −0.1724 *** (−3.34) | −0.1272 *** (−3.15) | −0.2086 *** (−3.97) | |

| −0.2084 (−0.34) | 0.6717 (1.31) | −0.2465 (−0.33) | |

| −0.2287 *** (−3.73) | −0.2021 *** (−3.70) | −0.2282 *** (−3.13) | |

| 0.4617 *** (8.04) | 0.4537 *** (11.19) | 0.5225 *** (6.78) | |

| −0.0052 (−0.39) | −0.0147 (−1.43) | −0.0321 * (−1.81) | |

| −0.1482 * (−1.91) | 0.0183 (0.23) | −0.0803 (−1.06) | |

| −0.0045 (−0.75) | −0.0001 (−0.03) | 0.0129 *** (3.06) | |

| 0.2753 *** (3.02) | 0.0878 (1.29) | −0.1661 * (−1.82) | |

| −0.2130 (−1.29) | −0.4497 *** (−3.40) | −0.7521 *** (−4.10) | |

| 0.0776 (0.98) | 0.0133 (0.24) | −0.0641 (−0.92) | |

| 13.6402 *** (12.21) | 11.2228 *** (13.50) | 11.7023 *** (9.21) | |

| 0.4331 | 0.5540 | 0.4886 |

| Region | 1999–2004 | 2005–2010 | 2011–2015 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern | 0.0059 (0.22) | −0.0461 * (−1.94) | −0.0040 (−0.16) |

| Central | 0.0215 (1.05) | −0.0053 (−0.23) | −0.0098 (−0.28) |

| Western | −0.0367 (−1.25) | −0.0233 (−1.03) | −0.0219 (−1.10) |

| Northeastern | −0.1724 *** (−3.34) | −0.1272 *** (−3.15) | −0.2086 *** (−3.97) |

| Variable | 1999–2004 | 2005–2010 | 2011–2015 |

|---|---|---|---|

| −0.2345 *** (−2.73) | −0.1817 *** (−3.21) | −0.1832 (−1.36) | |

| −0.0212 (−0.94) | −0.0471 *** (−2.77) | 0.0126 (0.41) | |

| −0.0002 (−0.03) | 0.0210 *** (3.42) | 0.0330 ** (2.21) |

| Variable | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| coefficient | −0.1634 *** (−3.31) | 0.8307 *** (3.05) | 0.7257 *** (10.95) | 0.0679 * (2.58) | 0.0068 (1.28) | −0.0158 (−0.81) | 0.0281 (9.42) | 475 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Zhou, X.; Chen, C.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Huan, F.; Wang, B. Enterprise Spatial Agglomeration and Economic Growth in Northeast China: Policy Implications for Uneven to Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11576. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511576

Zhang M, Zhou X, Chen C, Liu J, Li J, Huan F, Wang B. Enterprise Spatial Agglomeration and Economic Growth in Northeast China: Policy Implications for Uneven to Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11576. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511576

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Mingzhi, Xiangyu Zhou, Chao Chen, Jianxu Liu, Jiaxi Li, Fuying Huan, and Bowen Wang. 2023. "Enterprise Spatial Agglomeration and Economic Growth in Northeast China: Policy Implications for Uneven to Sustainable Development" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11576. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511576

APA StyleZhang, M., Zhou, X., Chen, C., Liu, J., Li, J., Huan, F., & Wang, B. (2023). Enterprise Spatial Agglomeration and Economic Growth in Northeast China: Policy Implications for Uneven to Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 15(15), 11576. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511576