This paper offers an exploratory analysis of the relationship between one sector (sport) and one concept (sustainability). If these two aspects have long been studied separately, examining the current junction between them is meaningful on both theoretical and practical levels. Thus, it is interesting to look at the way academics who are specialised in sport have paid attention to the concept of sustainability and the methods they used to conduct such surveys. It is also valuable to examine the relationship between theoretical issues and the strategies implemented by managers involved in the field of sport. In short, does theory meet practices and vice versa? Due to the exploratory dimension of this research, we did not have a guiding question when collecting our data. The process was rather based on an inductive rationale. However, some lessons can be learned from both the bibliometric analysis and from the interviews that were conducted.

4.1. Some Publications That Do Not Reflect the Whole Picture

In studying the sample, what we observe is that most of the academics who published some articles in the field are originally based in North America. This is in line with [

26] findings, which offer a bibliometric analysis of sport tourism and sustainability. Two hypotheses can be established to explain this observation. First, North American academics are the most important in numbers. As a result, their share in the total of authors who have examined these relationships between sport and sustainability is logically more significant. In that sense, their proportion could be similar to what is generally observed in the field of sport management, regardless of the topic: regarding the concept of sustainability, academics from Canada and the USA are the most important in numbers. Another explanation that could nevertheless be connected to the one above is the fact that issues about sport and sustainability are maybe especially crucial in North America. Indeed, in these countries, sport-related business has been in an advanced stage for many years. Therefore, being able to continue developing projects in this field while paying attention to their sustainable dimension is crucial.

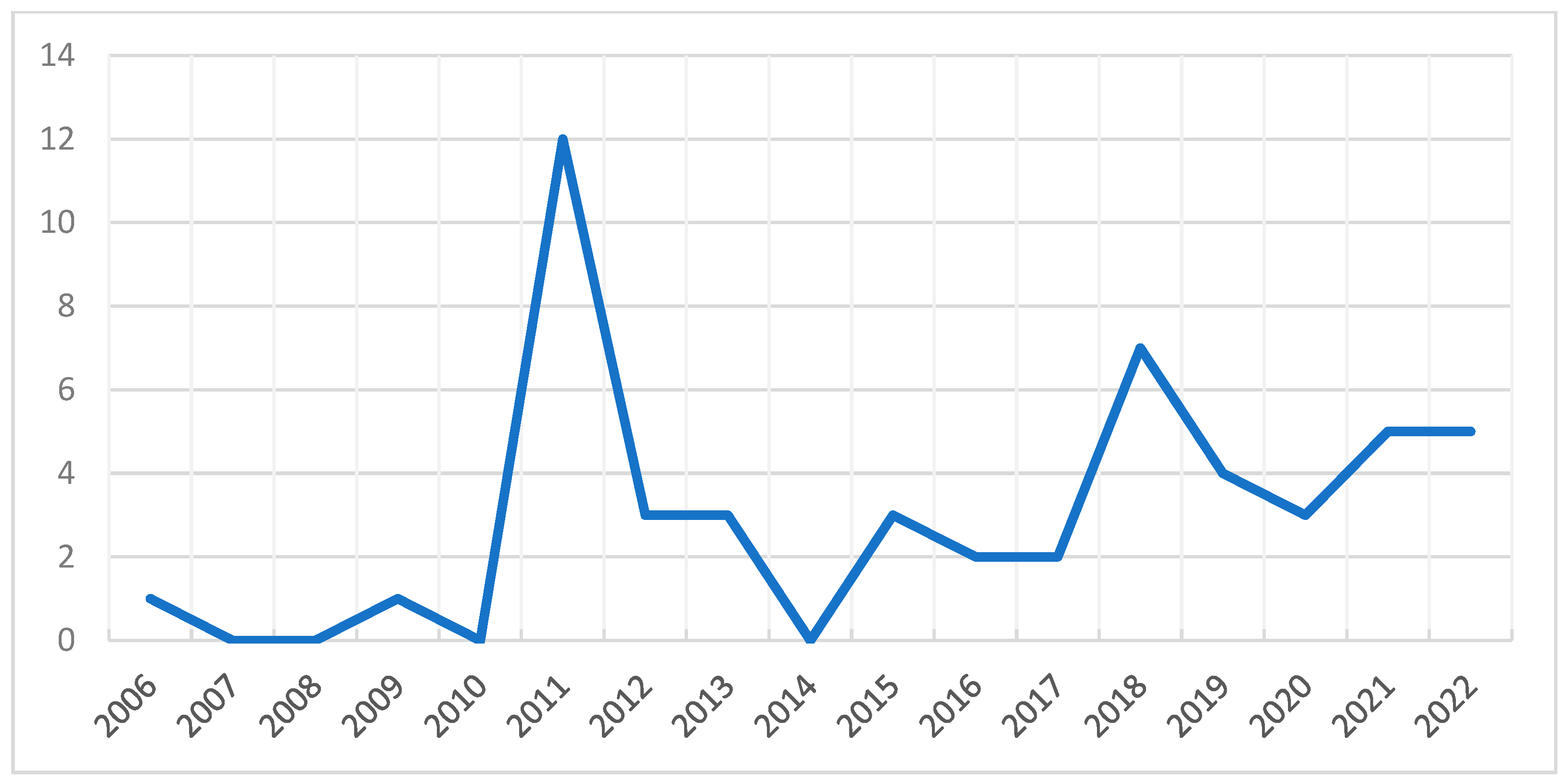

Secondly, it is interesting to notice that publications mixing sport and sustainability are not as recent as we might expect. If “sustainability in sport” can be perceived as a hot topic over the last few years, according to our sample, only a few publications were written over 15 years ago. This assertion backs [

26] since these authors even identified some articles in 2002. However, one finds different results in the distribution of the publications with regard to the date of publication. Ref. [

26] found a progressive increase in research topics including an expansive stage from 2016 to 2019. In our research, we did not notice such an expansion. An explanation could be that we did not use the same method to collect the data. Another hypothesis could be that there is a time gap between issues that are discussed within society (sustainability, especially in sport, has been a growing concern over the last few years) and their translation into academic work: academics focus on social issues after having the confirmation that the latter have become major. This statement would debunk the idea that sport is at the forefront of the contribution in analysing sustainability concerns. Additionally, when looking at the journals in which these kinds of works have been published, we could theoretically identify either journals that overview issues in sport in general and then accept a paper dealing with its connection to sustainability or journals that examine issues in sustainability and publish papers related to sport.

Thirdly, as expressed in

Table 1, sustainability in sport covers different dimensions. What we learnt from the bibliometric analysis is that these different dimensions are not equally examined. Three dimensions are over-studied: sport tourism, sporting events and professional sport are truly dominant. This can be noticed in the fact that these three dimensions cover the biggest stakes, the highest number of stakeholders and the most important businesses, which require a sustainable vigilance. As a supplementary approach, these three dimensions are definitely the most developed in North America. As we said, since this part of the world is also dominant in the authors’ countries of origin, this could explain why sport tourism, sport events and professional sport are the leading sectors when studying sustainability in sport.

Furthermore, another point can be made. As explained above, the concept of sustainability covers three major dimensions: economic, social and environmental. The latter is, without a doubt, the most examined dimension. This finding is in line with [

27] who, 15 years ago, already called for an integrative analysis of the concept of sustainability including these three dimensions. Environment-oriented studies are meaningful and reflect the fact that for numerous sport organisations, being involved in a sustainable process means promptly taking action in this particular dimension. This could be explained by the fact that there is a growing concern from the population (who are also the organisations’ customers) who cares more and more about these issues, which encourages companies/organisations to be, as a result, more involved as well. On the other hand, for sport organisations, performing better in this environmental dimension is maybe more visible and then more symbolically valuable, rather than having a real strategy with regard to the social or economic aspects of sustainability.

Beyond the aforementioned points, there are several comments to be made. Some of them can be seen as limitations. The first one deals with the theoretical dimension of the published works. Indeed, if the number of papers examining the relationships between sustainability and sport is quite significant, they do not seem to be anything more than applied studies. This is confirmed by the use of a very long list of theories (see

Table 5) that have been previously applied to other areas. In short, authors apply the concept of sustainability and its related theories to sport as they would to any other area (tourism, transport, industry, etc.). Accordingly, sport is nothing more than an application without, so far, any theoretical specificities. In order to make “sustainability in sport” a valuable field of research, further research should be conducted in order to identify some theoretical uniqueness. This limitation is in line with some former statements [

28,

29] underlining the lack of a scientific foundation or formalised definition of this concept. Thus, sustainability is not a theoretical model, just a topic of interest similar to environmentalism [

30,

31]. In their research, ref. [

26] share some insights mentioning that the theoretical framework of sustainability could be found within different subdisciplines such as organisational behaviour, marketing, psychology, communication, facility, law and governance, finance and economics.

Finally, our exploratory bibliometric analysis does not take into consideration some variables that could have been valuable in order to offer a more in-depth analysis: a greater number of published authors, more cited articles, authors’ universities of origin and co-occurrence of keywords along the period. This appears as a limitation of this study. One can refer to the work of [

26] for further analysis.

4.2. Contributions from the Industry within the Theoretical Background

Sustainability in sport is definitely an issue. As explained above, the first dimension which is at the core of the published works is the environmental dimension (or ecological impact). The interviews that we performed confirm this assertion. Thus, many sports, especially outdoor sports, require natural resources (like snow, ice or good quality of water [

32]). Going deeper into the understanding of natural management and compatibility between sport and natural resources is not only an issue for academics. It is also an issue for managers who lead businesses and have to find the most appropriate way to conduct the long-term development of their business through a sustainable perspective. The connection between these managers, academics and different organisations (such as POW (Protect Our Winter), which tries to defend a sustainable way to continue practicing skiing) that monitor the situation of our natural environment (storm activity, global warming, natural disasters) seems more and more crucial. This is an issue since [

33] noted that there is a disconnection between academics and practitioners within this space. This requires a better connection between stakeholders, including some strategies leading, for instance, to the construction and/or the renovation of sport facilities and/or the organisation of sporting events [

34].

One of the major conclusions that occurred during our interviews is the obligation to have a global vision of the problem. Most of the organisations focus on ecology first, but this seems to be only one aspect of the problem. Sport managers cannot improve a situation without taking into account social and economic aspects. Sharing the added value, thinking about the “fair” price to pay to have a sustainable event or product and defining the major stakeholders that have a bigger role in the problem are also crucial issues. This has already been confirmed by [

35] research.

A second interesting piece of information is the origin of the sustainable policy or strategy implemented by the organisation: all the persons interviewed underlined that individuals have made the shift far in advance before their organisation. Most of the persons we interviewed can in fact be considered as “pioneers” who influenced their organisation. It is very rare to have a collective reasoning before an individual one.

Of course, when the organisation needs to move forward with a concrete ecological implementation, this requires expensive means that imply a collective decision on a long-term perspective. This confirms some other results from previous research, such as the work of [

36]. Many facilities are currently implementing sustainable building improvements or construction principles, such as energy-saving lighting and low-flow faucets: those investments should last 20 to 30 years minimum.

Finally, those choices require a global agreement inside the organisation [

37] but also with all their stakeholders. For example, as ticketing has become a minor revenue in professional sport in North America and Europe [

38], sponsors and media, which represent 60 to 80% of those revenues, should be completely engaged in the process. This will actually be the most important issue for sporting event organisers that are mostly financed by corporate companies in the industries of airlines (Fly Emirates, Qatar Airways, Etihad, etc.), banks (that mostly finance the oil industry), gas (Gazprom, before the war in Ukraine, was one of the biggest sponsors in the world), or cars (Mercedes, BMW, Toyota, BYD, Peugeot, etc.).