Predicting Critical Factors Impacting Hotel Online Ratings: A Comparison of Religious and Commercial Destinations in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.2. Commercial and Religious Destinations

2.3. Online Ratings and Customer Satisfaction

2.4. Hotels’ Online Attributes and Customer Satisfaction

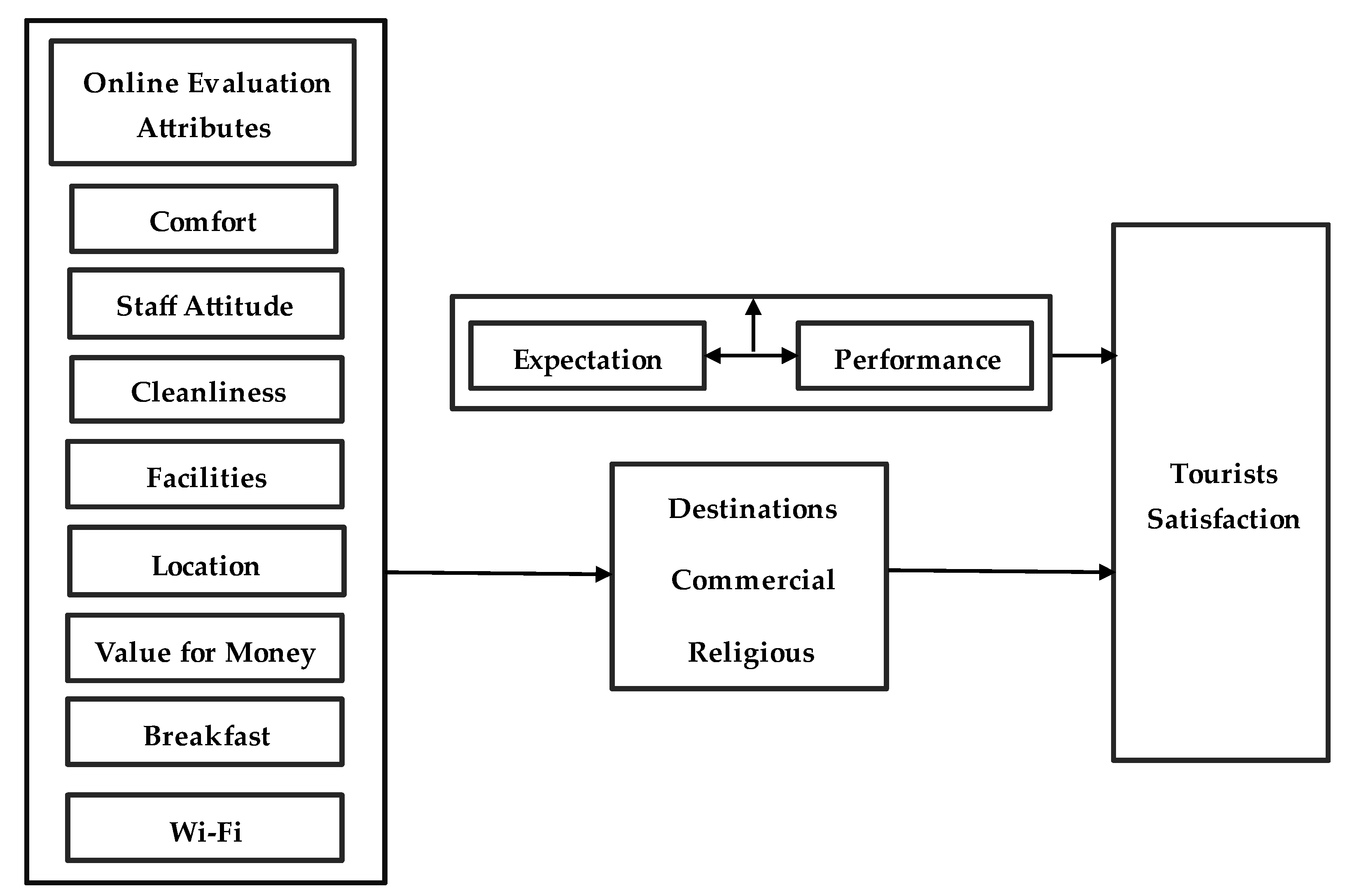

2.5. Hypotheses and Conceptual Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Variables and Measurement

3.3. Methods

3.3.1. Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA)

3.3.2. Implementation of IPA

3.3.3. Beta Regression Analysis

- Y = Overall rating representing customer satisfaction;

- COM = The numerical rating performance of the comfort attribute;

- STA = The numerical rating performance of the staff attitude attribute;

- CLE = The numerical rating performance of the cleanliness attribute;

- FAC = The numerical rating performance of the facilities’ attribute;

- LOC = The numerical rating performance of the location attribute;

- VFM = The numerical rating performance of the value for money attribute;

- BRE = The numerical rating performance of the breakfast attribute;

- WFS = The numerical rating performance of the Wi-Fi service attribute;

- ε = Error term.

4. Results and Discussion

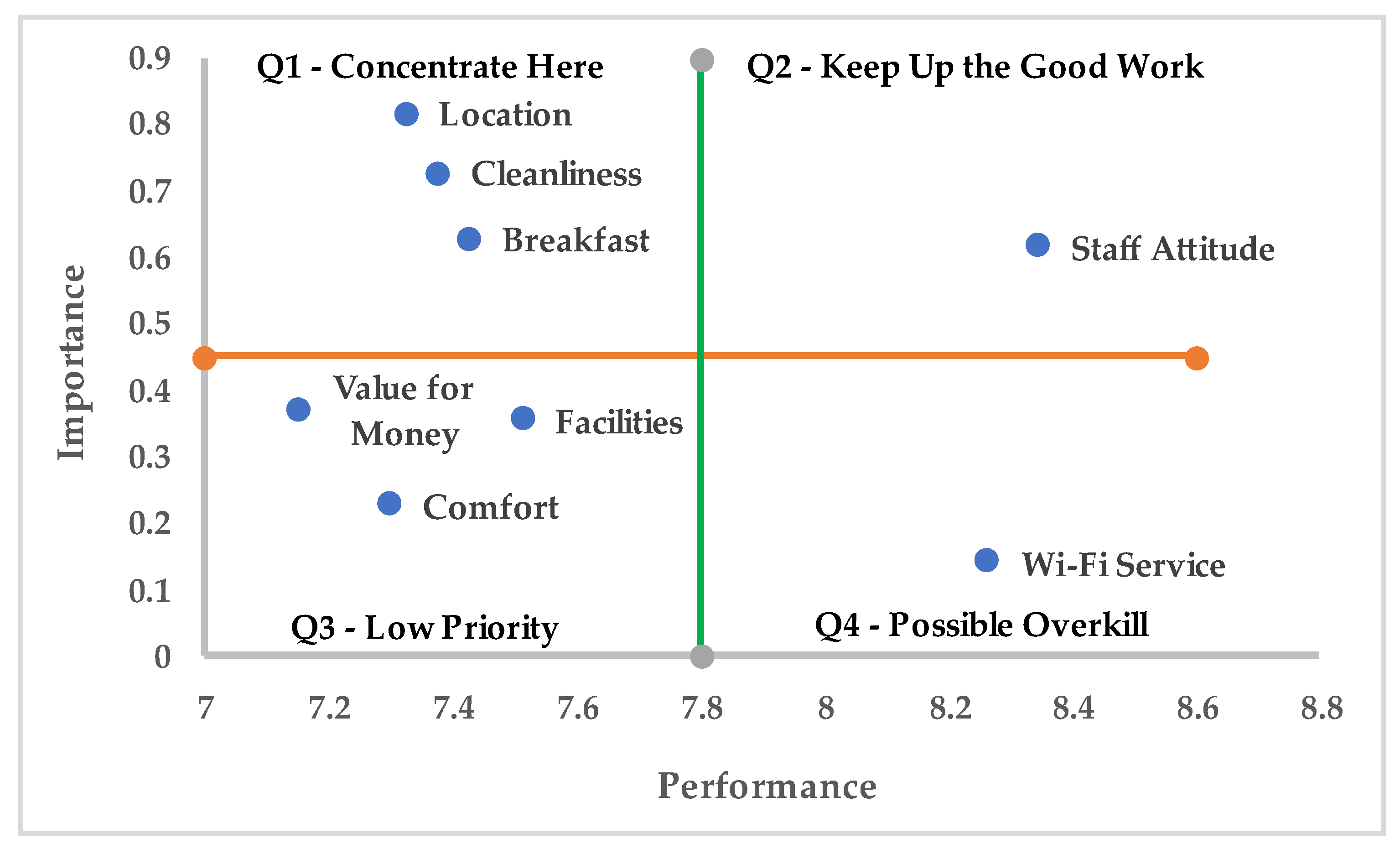

4.1. IPA Results

4.1.1. Discussion of IPA Results

Quadrant 1

Quadrant 2

Quadrant 3

Quadrant 4

4.2. Beta Regression Analysis Results

Discussion of Beta Regression Analysis Results

5. Conclusions and Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deng, W.J.; Yeh, M.L.; Sung, M.L. A Customer Satisfaction Index Model for International Tourist Hotels: Integrating Consumption Emotions into the American Customer Satisfaction Index. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Teeroovengadum, V.; Thomas, P.; Leonard, L. Integrating Service Quality as a Second-Order Factor in a Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty Model. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2978–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Kim, K. Customer Satisfaction, Service Quality, and Customer Value: Years 2000–2015. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, M. Predicting Overall Customer Satisfaction: Big Data Evidence from Hotel Online Textual Reviews. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udo, G.J.; Bagchi, K.K.; Kirs, P.J. An Assessment of Customers’ e-Service Quality Perception, Satisfaction and Intention. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2010, 30, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, R.W.Y.; Yeung, A.C.L.; Edwin Cheng, T.C. An Empirical Study of Employee Loyalty, Service Quality and Firm Performance in the Service Industry. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2010, 124, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, I.K.W.; Hitchcock, M. Importance–Performance Analysis in Tourism: A Framework for Researchers. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 242–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Zeng, H. Evaluation of Tourism E-Commerce User Satisfaction. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2021, 33, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Sharma, P.N.; Morgeson, F.V.; Zhang, Y. Antecedents and Consequences of Customer Satisfaction: Do They Differ Across Online and Offline Purchases? J. Retail. 2019, 95, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, A.A. Mobile Food Ordering Apps: An Empirical Study of the Factors Affecting Customer e-Satisfaction and Continued Intention to Reuse. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, A. User-Generated Content. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication Theory and Philosophy; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Tong, S. The Impact of User-Generated Content on Intention to Select a Travel Destination. J. Mark. Anal. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, V.; So, K.K.F.; Sparks, B. The Influence of Online Reviews on Consumers’ Attributions of Service Quality and Control for Service Standards in Hotels. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mauri, A.G.; Minazzi, R. Web Reviews Influence on Expectations and Purchasing Intentions of Hotel Potential Customers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neirotti, P.; Raguseo, E.; Paolucci, E. Are Customers’ Reviews Creating Value in the Hospitality Industry? Exploring the Moderating Effects of Market Positioning. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 1133–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, J.; Gretzel, U.; Law, R. Do Negative Experiences Always Lead to Dissatisfaction?—Testing Attribution Theory in the Context of Online Travel Reviews. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2010; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2010; pp. 297–308. [Google Scholar]

- Viglia, G.; Minazzi, R.; Buhalis, D. The Influence of E-Word-of-Mouth on Hotel Occupancy Rate. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2035–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiang, Z.; Du, Q.; Ma, Y.; Fan, W. A Comparative Analysis of Major Online Review Platforms: Implications for Social Media Analytics in Hospitality and Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Law, R.; Gu, B.; Chen, W. The Influence of User-Generated Content on Traveler Behavior: An Empirical Investigation on the Effects of e-Word-of-Mouth to Hotel Online Bookings. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-Y.; Pearce, P.L. Appraising Netnography: Towards Insights about New Markets in the Digital Tourist Era. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahoo Finance Fake Hotel Reviews? Never on Booking.Com, Says CEO. Available online: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/fake-hotel-reviews-never-booking-com-says-ceo-173948451.html (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Liu, Y.; Jang, S.C. Perceptions of Chinese Restaurants in the U.S.: What Affects Customer Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, C.; Ghose, A.; Wiesenfeld, B. Examining the Relationship Between Reviews and Sales: The Role of Reviewer Identity Disclosure in Electronic Markets. Inf. Syst. Res. 2008, 19, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Filieri, R.; McLeay, F. E-WOM and Accommodation: An Analysis of the Factors That Influence Travelers’ Adoption of Information from Online Reviews. J. Travel Res. 2013, 53, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raguseo, E.; Vitari, C. The Effect of Brand on the Impact of E-WOM on Hotels’ Financial Performance. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2017, 21, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabas, I.; Kareklas, I.; Weber, T.J.; Muehling, D.D. The Impact of Review Valence and Awareness of Deceptive Practices on Consumers’ Responses to Online Product Ratings and Reviews. J. Mark. Commun. 2021, 27, 685–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Cui, G.; Chung, Y.; Li, C. A Multi-Facet Item Response Theory Approach to Improve Customer Satisfaction Using Online Product Ratings. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2019, 47, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaley, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y.-K. Do Tipping Motivations Predict Loyalty to the Server in a Restaurant? Int. Hosp. Rev. 2019, 33, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, N.M.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Prayag, G. Psychological Determinants of Tourist Satisfaction and Destination Loyalty: The Influence of Perceived Overcrowding and Overtourism. J. Travel Res. 2023, 62, 644–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, S.; Jankovic, S.R. Exploring the Relationship between Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction in Creation Hotel Industry. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 19, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamad, I.A.; Singh, H.P. Decoding Significant and Trivial Factors Influencing Online Hotel Ratings: The Case of Saudi Arabia’s Makkah City. Int. Trans. J. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2021, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazytė, K.; Weber, F.; Schaffner, D. Sustainability Management of Hotels: How Do Customers Respond in Online Reviews? J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 18, 282–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.P.; Alhamad, I.A. Deciphering Key Factors Impacting Online Hotel Ratings through the Lens of Two-Factor Theory: A Case of Hotels in the Makkah City of Saudi Arabia. Int. Trans. J. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2021, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, W.; Lock-Teng Low, K. Are Travellers Satisfied with Malaysian Hotels? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 17, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T.; Caber, M. Prioritisation of the Hotel Attributes According to Their Influence on Satisfaction: A Comparison of Two Techniques. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ye, Q.; Law, R. Determinants of Customer Satisfaction in the Hotel Industry: An Application of Online Review Analysis. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 784–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, R.K.S.; Choi, T. An Importance-Performance Analysis of Hotel Selection Factors in the Hong Kong Hotel Industry: A Comparison of Business and Leisure Travellers. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanka, T.; Taylor, R. An Investigation into the Perceived Importance of Service and Facility Attributes to Hotel Satisfaction. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2004, 4, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, W.; Chan, A.; Mao, Z. Critical Success Factors and Customer Expectation in Budget Hotel Segment—A Case Study of China. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2009, 10, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, N.; Buhalis, D.; Law, R. Online Complaining Behavior in Mainland China Hotels: The Perception of Chinese and Non-Chinese Customers. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2014, 15, 248–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, S.; Heo, C.Y. Analysis of Satisfiers and Dissatisfiers in Online Hotel Reviews on Social Media. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1915–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Connor, P. User-Generated Content and Travel: A Case Study on Tripadvisor.Com. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2008; O’Connor, P., Höpken, W., Gretzel, U., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2008; pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, P.; Barnes, S.; Zigan, K.; Schegg, R. Understanding the Impact of Online Reviews on Hotel Performance. J. Travel Res. 2016, 56, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Öğüta, H.; Cezara, A. The Factors Affecting Writing Reviews in Hotel Websites. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 58, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Teichert, T.; Rossi, M.; Li, H.; Hu, F. Big Data for Big Insights: Investigating Language-Specific Drivers of Hotel Satisfaction with 412,784 User-Generated Reviews. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-C.; Ku, C.-H.; Chen, C.-H. Social Media Analytics: Extracting and Visualizing Hilton Hotel Ratings and Reviews from TripAdvisor. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 48, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, M.; Bélanger, C.H. Influence of Online Reviews on Student Satisfaction Seen through a Service Quality Model. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 3063–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedin, E.; Mendoza, A.; Karunasekera, S. Exploring the Moderating Role of Readers’ Perspective in Evaluations of Online Consumer Reviews. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 3406–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Wang, X.; Kim, E. Predicting Conversion Rates in Online Hotel Bookings with Customer Reviews. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 1264–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Fuentes, E. Are Guests of the Same Opinion as the Hotel Star-Rate Classification System? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2016, 29, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, X.; Hitt, L.M. Price Effects in Online Product Reviews: An Analytical Model and Empirical Analysis. MIS Q. 2010, 34, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamad, I.A.; Singh, H.P. Predicting Key Factors Impacting Online Hotel Ratings Using Data Mining Approach: A Case Study of the Makkah City of Saudi Arabia. Int. Trans. J. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2021, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.P.; Alhamad, I.A. A Novel Categorization of Key Predictive Factors Impacting Hotels’ Online Ratings: A Case of Makkah. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sann, R.; Lai, P.-C.; Liaw, S.-Y.; Chen, C.-T. Predicting Online Complaining Behavior in the Hospitality Industry: Application of Big Data Analytics to Online Reviews. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hassibi, S.; Nunkoo, R. A Systematic Review of Consumer Satisfaction Studies in Hospitality Journals: Conceptual Development, Research Approaches and Future Prospects. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 51–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, H.T.; Yang, S.-B. How Does Hotel Attribute Importance Vary among Different Travelers? An Exploratory Case Study Based on a Conjoint Analysis. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, D.A.; Collins, M.D.; Nale, R.D.; Barr, P.B. Measuring Service Quality in Mid-Scale Hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohirovich, T.K.; Mamarasulovna, T.Z. The Issue of Studying Religious Tourism in Uzbekistan. Int. J. Integr. Educ. 2020, 3, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, S.; King, B. Religious Tourism Studies: Evolution, Progress, and Future Prospects. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 45, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzidou, M.; Scarles, C.; Saunders, M.N.K. The Complexities of Religious Tourism Motivations: Sacred Places, Vows and Visions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 70, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Sánchez, A.; Álvarez-García, J.; del Río-Rama, M.; Oliveira, C. Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage: Bibliometric Overview. Religions 2018, 9, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsironis, C.N. Pilgrimage and Religious Tourism in Society, in the Wake of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Paradigmatic Focus on ‘St. Paul’s Route’ in the Central Macedonia Region, Greece. Religions 2022, 13, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcopolis How Al-Khobar Became the Industrial, Commercial, Tourism and Recreational Hub of the Eastern Province. Available online: https://marcopolis.net/how-al-khobar-became-the-industrial-commercial-tourism-and-recreational-hub-of-the-eastern-province.htm (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Saudi Gazette Full Text of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030|Al Arabiya English. Available online: https://english.alarabiya.net/en/perspective/features/2016/04/26/Full-text-of-Saudi-Arabia-s-Vision-2030.html (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Singh, H.P.; Singh, A.; Alam, F.; Agrawal, V. Impact of Sustainable Development Goals on Economic Growth in Saudi Arabia: Role of Education and Training. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi eVisa Welcome to the Saudi EVisa Portal. Available online: https://visa.visitsaudi.com/ (accessed on 7 April 2023).

- Yüksel, A.; Yüksel, F. The Expectancy-Disconfirmation Paradigm: A Critique. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2001, 25, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, R.N. An Experimental Study of Customer Effort, Expectation, and Satisfaction. J. Mark. Res. 1965, 2, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L.; Swan, J.E. Consumer Perceptions of Interpersonal Equity and Satisfaction in Transactions: A Field Survey Approach. J. Mark. 1989, 53, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L.; Swan, J.E. Equity and Disconfirmation Perceptions as Influences on Merchant and Product Satisfaction. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 16, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. An Attributional Theory of Achievement Motivation and Emotion. Psychol. Rev. 1985, 92, 548–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Magnusen, M.; Kim, Y.K. A Critical Review of Theoretical and Methodological Issues in Consumer Satisfaction Research and Recommendations for Future Sport Marketing Scholarship. J. Sport Manag. 2014, 28, 338–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehrer, A.; Crotts, J.C.; Magnini, V.P. The Perceived Usefulness of Blog Postings: An Extension of the Expectancy-Disconfirmation Paradigm. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S.; Porumbescu, G.A. Reconsidering the Expectancy Disconfirmation Model. Three Experimental Replications. Public Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 1272–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; Petrovsky, N.; Walker, R.M. The Expectancy-Disconfirmation Model and Citizen Satisfaction with Public Services: A Meta-analysis and an Agenda for Best Practice. Public Adm. Rev. 2022, 82, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.W.; Park, M.C. Antecedents of Customer Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty for Emerging Devices in the Initial Market of Korea: An Equity Framework. Psychol. Mark. 2013, 30, 676–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; van der Veen, R.; Li, G.; Chen, J.L. The Hong Kong Tourist Satisfaction Index. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 459–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.-F.; Chen, F.-S. Experience Quality, Perceived Value, Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions for Heritage Tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.C.; Huang, S. An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior Model for Tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2012, 36, 390–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Tribó, J.A. Customer Satisfaction and Brand Equity. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fu, X.; Liu, X.; Hua, C.; Li, Z.; Du, Q. Understanding Tour Guides’ Service Failure: Integrating a Two-Tier Triadic Business Model with Attribution Theory. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasco, A.; Buonincontri, P.; van Niekerk, M.; Orlowski, M.; Okumus, F. Exploring the Role of Next-Generation Virtual Technologies in Destination Marketing. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliman, N.K.; Hashim, S.M.; Wahid, S.D.M.; Harudin, S. Tourists’ Satisfaction with a Destination: An Investigation on Visitors to Langkawi Island. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2016, 8, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S.; Page, S.J. Destination Marketing Organizations and Destination Marketing: A Narrative Analysis of the Literature. Tour. Manag. 2014, 41, 202–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chi, C.G.-Q.; Qu, H. Examining the Structural Relationships of Destination Image, Tourist Satisfaction and Destination Loyalty: An Integrated Approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.A.; Gartner, W.C. Destination Image and Its Functional Relationships. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauhari, V.; Sanjeev, G.M. Managing Customer Experience for Spiritual and Cultural Tourism: An Overview. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2010, 2, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Tsai, D. How Destination Image and Evaluative Factors Affect Behavioral Intentions? Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachyuni, S.S.; Kusumaningrum, D.A. The Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic: How Are the Future Tourist Behavior? J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2020, 33, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcocer, N.H.; Ruiz, V.R.L. The Role of Destination Image in Tourist Satisfaction: The Case of a Heritage Site. Econ. Res. Istraž. 2020, 33, 2444–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Afshardoost, M.; Eshaghi, M.S. Destination Image and Tourist Behavioural Intentions: A Meta-Analysis. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fu, X.; Cai, L.A.; Lu, L. Destination Image and Tourist Loyalty: A Meta-Analysis. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, L. A Review on Tourist Satisfaction of Tourism Destinations. In LISS 2012: Proceedings of 2nd International Conference on Logistics, Informatics and Service Science; Zhang, Z., Zhang, R., Zhang, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; Beijing, China, 2013; pp. 593–604. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, W.; Zeng, S.; Cheng, P.S.-T. The Influence of Destination Image and Tourist Satisfaction on Tourist Loyalty: A Case Study of Chinese Tourists in Korea. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 10, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.G. Religious Tourism—A Review of the Literature. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2018, 1, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamediana-Pedrosa, J.D.; Vila-López, N.; Küster-Boluda, I. Predictors of Tourist Engagement: Travel Motives and Tourism Destination Profiles. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 16, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantziantoniou, A.; Dionysopoulou, P. The Religious Tourism in Greece: Case Study of Saint John Russian in N. Evia. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2017, 3, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, R.; Griffin, K.; Blackwell, R. Motivations for Religious Tourism, Pilgrimage, Festivals and Events. In Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage Management: An International Perspective; Raj, R., Griffin, K., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2015; ISBN 9781780645230. [Google Scholar]

- Liro, J. Visitors’ Motivations and Behaviours at Pilgrimage Centres: Push and Pull Perspectives. J. Herit. Tour. 2021, 16, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, E.; Piramanayayagam, S.; Björk, P. Tourists’ Motivations, Emotions, and Memorable Local Food Experiences. J. Gastron. Tour. 2020, 5, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomfret, G. Conceptualising Family Adventure Tourist Motives, Experiences and Benefits. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2019, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.; Kozak, M.; Ferradeira, J. From Tourist Motivations to Tourist Satisfaction. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2013, 7, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, D. The Evolution of Religious Tourism: Concept, Segmentation and Development of New Identities. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.; Huck, L.; Robinson, R.N.S.; Stettler, J. Commercial Hospitality in Tourism: A Global Comparison of What Culturally Matters. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhas, P.S.; Manrai, L.A.; Manrai, A.K. Role of Tourist Destination Development in Building Its Brand Image: A Conceptual Model. J. Econ. Financ. Adm. Sci. 2016, 21, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abbate, C.S.; Di Nuovo, S. Motivation and Personality Traits for Choosing Religious Tourism. A Research on the Case of Medjugorje. Curr. Issues Tour. 2013, 16, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kádár, B.; Gede, M. Tourism Flows in Large-Scale Destination Systems. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 87, 103113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, R.; Sinha, P. Framework for a Resilient Religious Tourism Supply Chain for Mitigating Post-Pandemic Risk. Int. Hosp. Rev. 2022, 36, 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanelli, M.; Gazzola, P.; Grechi, D.; Pollice, F. Towards a Sustainability-oriented Religious Tourism. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2021, 38, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.; Antonio, N.; de Almeida, A.; Nunes, L. The Influence of Geographic and Psychic Distance on Online Hotel Ratings. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 722–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teare, R. Services Management: The New Paradigm in Hospitality. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 17, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kandampully, J. Services Management: The New Paradigm in Hospitality; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dotson, J.P.; Allenby, G.M. Investigating the Strategic Influence of Customer and Employee Satisfaction on Firm Financial Performance. Mark. Sci. 2010, 29, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Griffin, M. The Nature of Satisfaction: An Updated Examination and Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 1998, 41, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsky, J.D. Customer Satisfaction in the Hotel Industry. Hosp. Res. J. 1992, 16, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fen, Y.S.; Lian, K.M. Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction: Antecedents of Customer’s Re-Patronage Intentions. Sunway Acad. J. 2007, 4, 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M.; Rimmington, M. Tourist Satisfaction with Mallorca, Spain, as an Off-Season Holiday Destination. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, A. Tourist Satisfaction and Complaining Behavior: Measurement and Management Issues in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry; Nova Kroshka Books: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Bowen, J.T.; Baloglu, S. Marketing for Hospitality and Tourism, 8th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Abdou, A.H.; Shehata, H.S.; Mahmoud, H.M.E.; Albakhit, A.I.; Almakhayitah, M.Y. The Effect of Environmentally Sustainable Practices on Customer Citizenship Behavior in Eco-Friendly Hotels: Does the Green Perceived Value Matter? Sustainability 2022, 14, 7167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.; Borghi, M. Environmental Discourse in Hotel Online Reviews: A Big Data Analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 829–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Xue, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. Green Image and Consumers’ Word-of-Mouth Intention in the Green Hotel Industry: The Moderating Effect of Millennials. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Martín, M.Á.; Folgado-Fernández, J.A.; Palos-Sánchez, P.R.; Castejón-Jiménez, P. The Impact of the Environmental Quality of Online Feedback and Satisfaction When Exploring the Critical Factors for Luxury Hotels. Sustainability 2019, 12, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tran, H.; Hwang, Y.; Yu, C.; Yoo, S. The Effect of Destination Social Responsibility on Tourists’ Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Emotions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ding, C.; Guo, Q.; Rehman, A.; Zeeshan, M. Impact of Environment on Hotel Customer Satisfaction in Southeast Asia: A Study of Online Booking Site Reviews. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 978070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Gretzel, U. Role of Social Media in Online Travel Information Search. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, N.L.; Guillet, B.D. Investigation of Social Media Marketing: How Does the Hotel Industry in Hong Kong Perform in Marketing on Social Media Websites? J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2011, 28, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.; Law, R.; van Hoof, H.; Buhalis, D. Social Media in Tourism and Hospitality: A Literature Review. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Stock, D.; McCarthy, L. Customer Preferences for Online, Social Media, and Mobile Innovations in the Hospitality Industry. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2012, 53, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berezina, K.; Bilgihan, A.; Cobanoglu, C.; Okumus, F. Understanding Satisfied and Dissatisfied Hotel Customers: Text Mining of Online Hotel Reviews. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.E.; Duan, W.; Boo, S. An Analysis of One-Star Online Reviews and Responses in the Washington, D.C., Lodging Market. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2013, 54, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilan, D.; Avello, M.; Martinez-Navarro, G. The Influence of Online Ratings and Reviews on Hotel Booking Consideration. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Fang, D. How Power Distance Affects Online Hotel Ratings: The Positive Moderating Roles of Hotel Chain and Reviewers’ Travel Experience. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringam, B.B.; Gerdes, J. An Analysis of Word-of-Mouse Ratings and Guest Comments of Online Hotel Distribution Sites. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 773–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Ryan, B.; Chu, R. The Importance of Hotel Attributes in Contributing to Travelers’ Satisfaction in the Hong Kong Hotel Industry. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2000, 1, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, H.M. Motivation-Hygiene Theory of Job Attitudes: An Empirical Investigation and an Attempt to Reconcile Both the One- and the Two-Factor Theories of Job Attitudes. J. Appl. Psychol. 1970, 54, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddox, R.N. Two-Factor Theory and Consumer Satisfaction: Replication and Extension. J. Consum. Res. 1981, 8, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, F.; Mausner, B.; Snyderman, B.B. The Motivation to Work; Routledge: London, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Cadotte, E.R.; Turgeon, N. Dissatisfiers and Satisfiers: Suggestions from Consumer Complaints and Compliments. J. Consum. Satisf. Dissatisf. Complain. Behav. 1988, 1, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, P. Managing a Hotel’s Image on TripAdvisor. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 754–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, M.; Santaló, J.; Silva, R. Being Better vs. Being Different: Differentiation, Competition, and Pricing Strategies in the Spanish Hotel Industry. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suanmali, S. Factors Affecting Tourist Satisfaction: An Empirical Study in the Northern Part of Thailand. In Proceedings of the SHS Web of Conferences, 4th International Conference on Tourism Research (4ICTR), Kola Kinabalu, Malaysia, 9–11 December 2014; Othuman Mydin, M.A., Marzuki, A., Eds.; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2014; Volume 12, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Awan, M.I.; Shamim, A.; Ahn, J. Implementing ‘Cleanliness Is Half of Faith’ in Re-Designing Tourists, Experiences and Salvaging the Hotel Industry in Malaysia during COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Islam. Mark. 2021, 12, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsky, J.D.; Labagh, R. A Strategy for Customer Satisfaction. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 1992, 33, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Ryan, C. Place Attachment, Identity and Community Impacts of Tourism—The Case of a Beijing Hutong. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Song, T.H. The Differential Motivation and Context Effects of Cause-Related Marketing in the Hotel Industry: The Moderating Role of Consumption Value. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.; Yeung, M.A. Brand Prestige and Affordable Luxury: The Role of Hotel Guest Experiences. J. Vacat. Mark. 2020, 26, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Foerste, M. SoCoMo Marketing for Travel and Tourism: Empowering Co-Creation of Value. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulchand-Gidumal, J.; Melián-González, S.; González López-Valcárcel, B. Improving Hotel Ratings by Offering Free Wi-Fi. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2011, 2, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, J.-I.; Wu, H.-H. Applying Importance-Performance Analysis to Compare the Changes of a Convenient Store. Qual. Quant. 2009, 43, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cribari-Neto, F.; Zeileis, A. Beta Regression in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 34, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martilla, J.A.; James, J.C. Importance-Performance Analysis. J. Mark. 1977, 41, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavas, U.; Shemwell, D.J. Modified Importance-performance Analysis: An Application to Hospitals. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2001, 14, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrant, M.A.; Smith, E.K. The Use of a Modified Importance-Performance Framework to Examine Visitor Satisfaction with Attributes of Outdoor Recreation Settings. Manag. Leis. 2002, 7, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Yen, T.; Tsai, C. Modify IPA for Quality Improvement: Taguchi’s Signal-to-noise Ratio Approach. TQM J. 2008, 20, 488–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-C.; Yen, T.-M.; Tsai, C.-H. Using Importance-Performance Analysis and Decision Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory to Enhance Order-Winner Criteria—A Study of Computer Industry. Inf. Technol. J. 2008, 7, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deng, W.-J.; Kuo, Y.-F.; Chen, W.-C. Revised Importance–Performance Analysis: Three-Factor Theory and Benchmarking. Serv. Ind. J. 2008, 28, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-P.; Chan, Y.-H.; Tsai, M.-C. A Transformation Function Corresponding to IPA and Gap Analysis. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2009, 20, 829–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.-Y.; Lee, Y.-C.; Yen, T.-M.; Tsai, C.-H. Using BPNN and DEMATEL to Modify Importance–Performance Analysis Model—A Study of the Computer Industry. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 9969–9979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.-H.; Feng, S.-Y.; Yen, T.-M. Using Modified IPA to Improve Service Quality of Standard Hotel in Taiwan. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2014, 7, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dwyer, L.; Armenski, T.; Cvelbar, L.K.; Dragićević, V.; Mihalic, T. Modified Importance-Performance Analysis for Evaluating Tourism Businesses Strategies: Comparison of Slovenia and Serbia. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-K. A New Approach for Diagonal Line Model of Importance-Performance Analysis: A Case Study of Tourist Satisfaction in China. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 215824402198927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormanović, S.; Ćirić, A.; Talović, M.; Alić, H.; Jelešković, E.; Čaušević, D. Importance-Performance Analysis: Different Approaches. Acta Kinesiol. 2017, 11, 56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wyród-Wróbel, J.; Biesok, G. Decision Making on Various Approaches to Importance-Performance Analysis. Eur. J. Bus. Sci. Technol. 2017, 3, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Albayrak, T. Importance Performance Competitor Analysis (IPCA): A Study of Hospitality Companies. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 48, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERVQUAL: A Multi-Item Scale of Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Service Quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, L.S.L.; To, W.M. Importance-performance Analysis for Public Management Decision Making. Manag. Decis. 2010, 48, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taplin, R.H. Competitive Importance-Performance Analysis of an Australian Wildlife Park. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, E.; Qu, H.; Njite, D.U.S. Customer Perceptions Toward Chinese Restaurant Service Quality: An Importance and Performance Approach. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2011, 14, 290–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, M.P.; Havitz, M.E. Destination Appraisal. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Q.; Chow, I. Application of Importance-Performance Model in Tour Guides’ Performance: Evidence from Mainland Chinese Outbound Visitors in Hong Kong. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L.D.; Karwan, K.R.; Scribner, L.L. Service Quality Measurement and the Disconfirmation Model: Taking Care in Interpretation. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2003, 14, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalo, J.; Varela, J.; Manzano, V. Importance Values for Importance–Performance Analysis: A Formula for Spreading out Values Derived from Preference Rankings. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, D.R. A Comparison of Approaches to Importance-Performance Analysis. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 45, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruyere, B.L.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Vaske, J.J. Enhancing Importance-Performance Analysis through Segmentation. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2002, 12, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, K.-J. Impact-Range Performance Analysis and Asymmetry Analysis for Improving Quality of Korean Food Attributes. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, S.E.; Showalter, M.J. The Performance-Importance Response Function: Observations and Implications. Serv. Ind. J. 1999, 19, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, K.; Sauerwein, E.; Heischmidt, K. Importance-Performance Analysis Revisited: The Role of the Factor Structure of Customer Satisfaction. Serv. Ind. J. 2003, 23, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, W.; Newman, J. Multiattribute Evaluation; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1982; ISBN 9780803900950. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.A. Assessing Regression-Based Importance Weights for Quality Perceptions and Satisfaction Judgements in the Presence of Higher Order and/Orinteraction Effects. J. Retail. 1997, 73, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-S.; Chen, H.-T. Applying Importance–Performance Analysis with Simple Regression Model and Priority Indices to Assess Hotels’ Service Performance. J. Test. Eval. 2014, 42, 20130124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.-H.; Feng, S.-Y.; Lee, Y.-C.; Yen, T.-M. Using Modified IPA to Evaluate Supplier’s Performance: Multiple Regression Analysis and DEMATEL Approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 7102–7109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T.; Caber, M.; Rosario González-Rodríguez, M.; Aksu, A. Analysis of Destination Competitiveness by IPA and IPCA Methods: The Case of Costa Brava, Spain against Antalya, Turkey. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Cao, X.; Huang, X.; Cao, X. Applying the IPA–Kano Model to Examine Environmental Correlates of Residential Satisfaction: A Case Study of Xi’an. Habitat Int. 2016, 53, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramanathan, R.; Ramanathan, U. A New Rational IPA and Application to Cruise Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 61, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, H.-Y.; Chiu, S.-I.; Cheng, C.-C.; Yen, T.-M. Applying the IPA and DEMATEL Models to Improve the Order-Winner Criteria: A Case Study of Taiwan’s Network Communication Equipment Manufacturing Industry. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 9674–9683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.Y.; Chu, R. Levels of Satisfaction among Asian and Western Travellers. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2000, 17, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cezar, A.; Ögüt, H. Analyzing Conversion Rates in Online Hotel Booking: The Role of Customer Reviews, Recommendations and Rank Order in Search Listings. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 286–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Li, G.; Liu, Z. Zero-Inflated Beta Regression for Differential Abundance Analysis with Metagenomics Data. J. Comput. Biol. 2016, 23, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Kong, Y. Zoib: An R Package for Bayesian Inference for Beta Regression and Zero/One Inflated Beta Regression. R J. 2015, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Figueroa-Zúñiga, J.I.; Arellano-Valle, R.B.; Ferrari, S.L.P. Mixed Beta Regression: A Bayesian Perspective. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2013, 61, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gujarati, D.N.; Porter, D.C. Basic Econometrics, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill Irwin: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, R.M. A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halunga, A.G.; Orme, C.D.; Yamagata, T. A Heteroskedasticity Robust Breusch–Pagan Test for Contemporaneous Correlation in Dynamic Panel Data Models. J. Econ. 2017, 198, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, H.P.; Alhulail, H.N. Information Technology Governance and Corporate Boards’ Relationship with Companies’ Performance and Earnings Management: A Longitudinal Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rountree, K.; Swatos, W.H.; Tomasi, L. From Medieval Pilgrimage to Religious Tourism: The Social and Cultural Economics of Piety. Sociol. Relig. 2005, 66, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attributes | Commercial Destination | Religious Destination | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heteroscedasticity | VIF | Heteroscedasticity | VIF | |

| Comfort (COM) | 0.027 | 2.556 | 0.031 | 3.002 |

| Staff Attitude (STA) | 0.004 | 1.872 | 0.012 | 2.017 |

| Cleanliness (CLE) | 0.030 | 1.665 | 0.026 | 1.945 |

| Facilities (FAC) | 0.034 | 2.083 | 0.037 | 2.223 |

| Location (LOC) | 0.011 | 2.175 | 0.019 | 2.684 |

| Value for Money (VFM) | 0.022 | 1.689 | 0.025 | 2.441 |

| Breakfast (BRE) | 0.003 | 1.528 | 0.011 | 1.539 |

| Wi-Fi Service (WFS) | 0.037 | 2.974 | 0.022 | 1.770 |

| Attributes | Means (Performance) | SD | B | β (Importance) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comfort (COM) | 7.639 | 1.273 | 0.804 | 0.792 |

| Staff Attitude (STA) | 8.264 | 1.062 | 0.573 | 0.561 |

| Cleanliness (CLE) | 7.883 | 0.898 | 0.588 | 0.571 |

| Facilities (FAC) | 7.885 | 1.336 | 0.773 | 0.765 |

| Location (LOC) | 7.793 | 1.114 | 0.197 | 0.185 |

| Value for Money (VFM) | 7.731 | 0.857 | 0.675 | 0.668 |

| Breakfast (BRE) | 8.615 | 1.011 | 0.518 | 0.531 |

| Wi-Fi Service (WFS) | 7.742 | 1.126 | 0.102 | 0.091 |

| Grand Mean | 7.944 | 0.521 |

| Attributes | Means (Performance) | SD | B | β (Importance) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comfort (COM) | 7.297 | 0.985 | 0.239 | 0.229 |

| Staff Attitude (STA) | 8.342 | 1.044 | 0.631 | 0.619 |

| Cleanliness (CLE) | 7.374 | 1.183 | 0.735 | 0.729 |

| Facilities (FAC) | 7.511 | 0.852 | 0.373 | 0.357 |

| Location (LOC) | 7.323 | 1.027 | 0.835 | 0.818 |

| Value for Money (VFM) | 7.151 | 1.119 | 0.377 | 0.371 |

| Breakfast (BRE) | 7.424 | 0.986 | 0.641 | 0.631 |

| Wi-Fi Service (WFS) | 8.262 | 1.125 | 0.152 | 0.143 |

| Grand Mean | 7.586 | 0.487 |

| Un-Standardized Coefficient | Standardized Coefficient | T | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | β | |||

| Constant | 7.351 | 1.169 | 6.288 | 0.000 | |

| Comfort (COM) | 0.378 | 0.079 | 0.371 | 4.785 | 0.002 |

| Staff Attitude (STA) | 0.229 | 0.064 | 0.216 | 3.578 | 0.009 |

| Cleanliness (CLE) | 0.261 | 0.078 | 0.251 | 3.346 | 0.012 |

| Facilities (FAC) | 0.336 | 0.087 | 0.322 | 3.862 | 0.006 |

| Location (LOC) | 0.152 | 0.054 | 0.136 | 2.815 | 0.026 |

| Value for Money (VFM) | 0.297 | 0.076 | 0.289 | 3.908 | 0.006 |

| Breakfast (BRE) | 0.202 | 0.051 | 0.191 | 3.961 | 0.005 |

| Wi-Fi Service (WFS) | 0.141 | 0.054 | 0.128 | 2.611 | 0.035 |

| Un-Standardized Coefficient | Standardized Coefficient | T | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | β | |||

| Constant | 5.748 | 0.916 | 6.275 | 0.000 | |

| Comfort (COM) | 0.204 | 0.069 | 0.195 | 2.957 | 0.021 |

| Staff Attitude (STA) | 0.258 | 0.081 | 0.241 | 3.185 | 0.015 |

| Cleanliness (CLE) | 0.319 | 0.077 | 0.308 | 4.143 | 0.004 |

| Facilities (FAC) | 0.213 | 0.078 | 0.201 | 2.731 | 0.029 |

| Location (LOC) | 0.347 | 0.068 | 0.339 | 5.103 | 0.001 |

| Value for Money (VFM) | 0.238 | 0.086 | 0.223 | 2.767 | 0.028 |

| Breakfast (BRE) | 0.279 | 0.076 | 0.261 | 3.671 | 0.008 |

| Wi-Fi Service (WFS) | 0.175 | 0.066 | 0.163 | 2.652 | 0.033 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Singh, H.P.; Alshallaqi, M.; Altamimi, M. Predicting Critical Factors Impacting Hotel Online Ratings: A Comparison of Religious and Commercial Destinations in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11998. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511998

Singh HP, Alshallaqi M, Altamimi M. Predicting Critical Factors Impacting Hotel Online Ratings: A Comparison of Religious and Commercial Destinations in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11998. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511998

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingh, Harman Preet, Mohammad Alshallaqi, and Mohammed Altamimi. 2023. "Predicting Critical Factors Impacting Hotel Online Ratings: A Comparison of Religious and Commercial Destinations in Saudi Arabia" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11998. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511998

APA StyleSingh, H. P., Alshallaqi, M., & Altamimi, M. (2023). Predicting Critical Factors Impacting Hotel Online Ratings: A Comparison of Religious and Commercial Destinations in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 15(15), 11998. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511998