Promoting Sustainable Food Practices in Food Service Industry: An Empirical Investigation on Saudi Arabian Restaurants

Abstract

1. Introduction

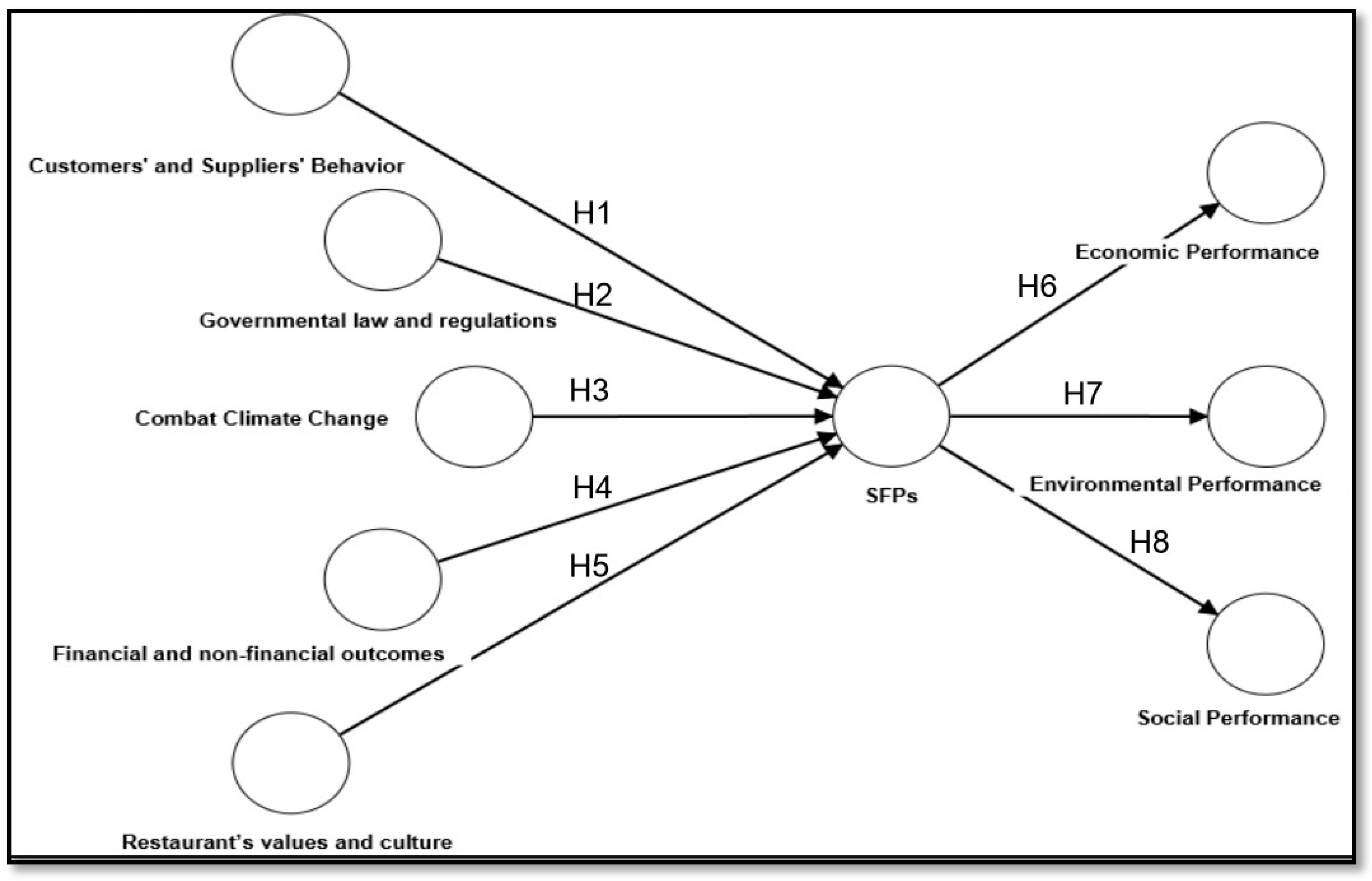

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Sustainable Food Practices in the Food Service Industry

2.2. Factors Affecting Promoting Sustainable Food Practices

2.3. Sustainable Food Practices and Economic Performance

2.4. Sustainable Food Practices and Environmental Performance

2.5. Sustainable Food Practices and Social Performance

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measures and Instrument Development

3.2. Data Collection and Sampling

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Variance (CMV)

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Multicollinearity Statistics

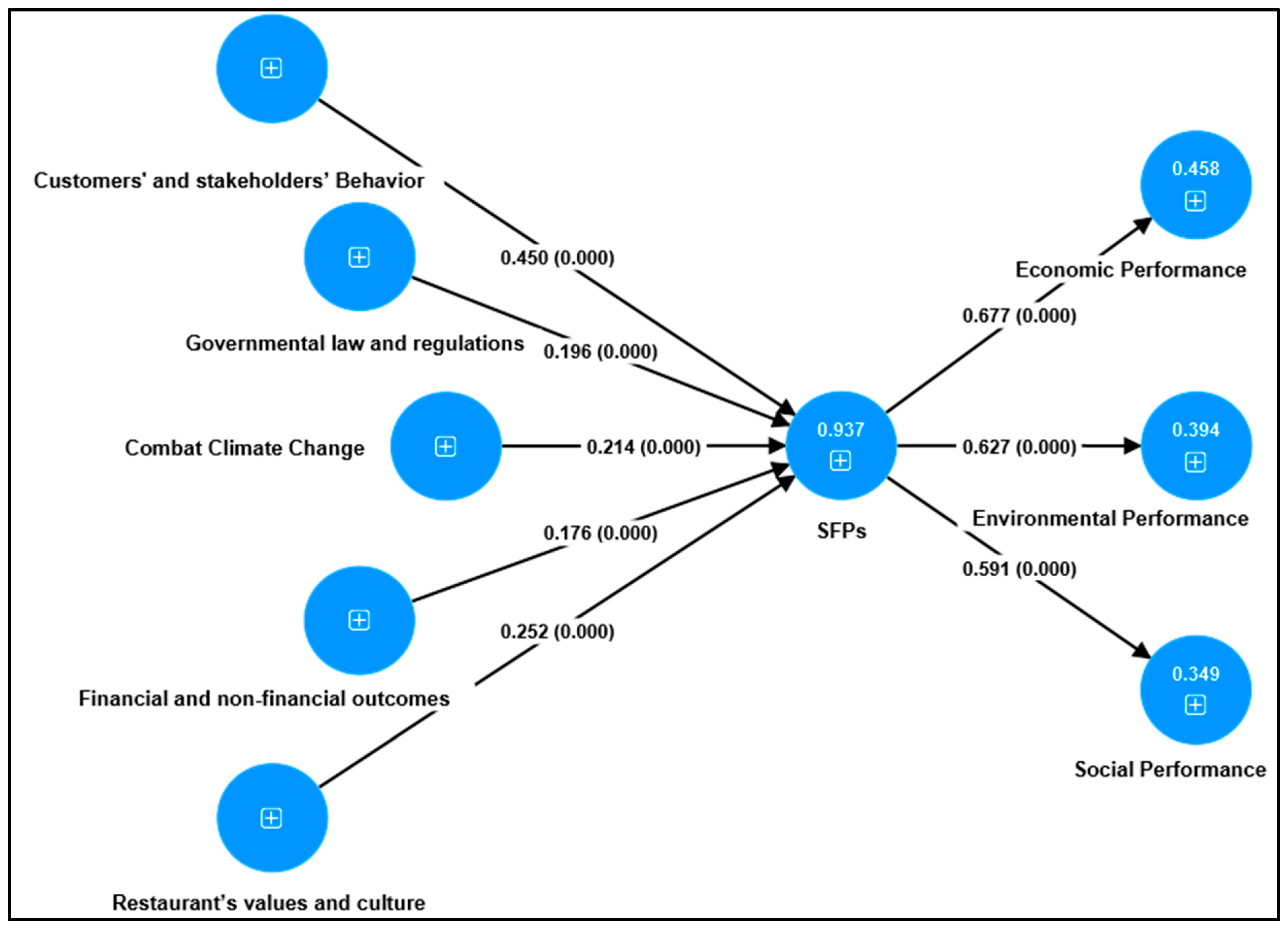

4.4. The Effectiveness of the Structural Model

4.5. Testing the Study Hypotheses

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Conclusions and Limitations of This Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Items | Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Customers’ and stakeholders’ sustainable behaviors (C&SSB) | C&SSB1 | Your decision to promote SFPs is influenced by the increase in consumers’ demand for sustainable products and services. |

| C&SSB2 | Your main customer is concerned with sustainable products/services and their impacts on the environment. | |

| C&SSB3 | Your main customer is willing to pay extra for sustainably produced food. | |

| C&SSB4 | Your decision to promote SFPs is influenced by the pressure from food suppliers. | |

| C&SSB5 | Your food supplier is familiar with the concept of SFPs. | |

| C&SSB6 | Your competitors are interested in adopting SFPs. | |

| Governmental law and regulations around sustainability (G&LR) | GL&R1 | Your decision to promote SFPs is influenced by the increasing regulations and laws around sustainability. |

| GL&R2 | The current governmental laws and regulations related to SFPs are effective. | |

| GL&R3 | The government is doing enough to promote SFPs (i.e., incentivizing sustainable production or penalizing unsustainable practices). | |

| The commitment to combat climate change (CC) | CC1 | Your decision to promote SFPs is influenced by the restaurant’s commitment to reducing negative environmental impacts. |

| CC2 | Investing in sustainable sourcing practices is important for mitigating the effects of climate change. | |

| Financial and non-financial outcomes of adopting SFPs (F&NF) | F&NF1 | Your decision to promote SFPs is influenced by the financial benefits obtained (i.e., reduction of operational cost, and increase of sales). |

| F&NF2 | Your decision to promote SFPs is influenced by the competitive advantage gained (The opportunity to differentiate the restaurant from the competition). | |

| Restaurant’s values and culture toward sustainability (RV&C) | RV&C1 | Your decision to promote SFPs is influenced by the restaurant’s values and culture toward sustainability. |

| RV&C2 | You believe that initiating a path toward sustainability is imperative. | |

| RV&C3 | SFPs are the top priority for your restaurant. | |

| RV&C4 | Restaurant management makes a concerted effort to stay up to date with sustainability trends within the restaurant industry. | |

| Sustainable Food Practices (SFPs) | SFP1 | Purchasing seasonally and locally produced foods. |

| SFP2 | Using sustainable packaging materials that are biodegradable or recyclable. | |

| SFP3 | Purchasing energy-efficient kitchen equipment and appliances. | |

| SFP4 | Implementing water-saving measures. | |

| SFP5 | Incorporating plant-based menu options to promote healthier and more sustainable diets. | |

| SFP6 | Incorporating organic food into your daily menu. | |

| SFP7 | Donating excess food to food banks or other charitable organizations. | |

| SFP8 | Educating customers and employees about sustainable food practices. | |

| SFP9 | Reducing solid and liquid wastes. | |

| SFP10 | Composting kitchen wastes. | |

| Economic performance | ECO1 | Increasing the restaurant’s sales volume and profit margin |

| ECO2 | Reducing restaurant’s operational costs (i.e., energy and water consumption costs) in the long term. | |

| ECO3 | Increasing the restaurant’s market share. | |

| Environmental performance | ENVR1 | Mitigating climate change and ecological degradation. |

| ENVR2 | Enhancing the restaurant’s environmental situation. | |

| ENVR3 | Decreasing the level of greenhouse gas emissions. | |

| ENVR4 | Lowering waste generation, water, and energy consumption. | |

| Social performance | SOC1 | Improving the quality of life. |

| SOC2 | Increasing employment opportunities and strengthening the restaurant’s relationship with the local community. | |

| SOC3 | Increasing employee and customer social responsibility. |

References

- Research and Markets. Saudi Arabia Foodservice Market—Growth, Trends, and Forecasts (2023–2028). 2023. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5318422/saudi-arabia-foodservice-market-growth?gclid=CjwKCAjwyqWkBhBMEiwAp2yUFrHT1Dy-8p_4hewxLFWxZ8EFVR0zNZvr1-HPak0OM5xM-EfvkbhauRoCnmYQAvD_BwE (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Fortune Business Insights. Saudi Arabia Foodservice Market Size, Share, and COVID-19 Impact Analysis, by Type (Full Service Restaurants, Quick Service Restaurants, Institutes, and Others), Service Type (Commercial and Institutional), 2022–2029. 2023. Available online: https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/saudi-arabia-food-service-market-106896 (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- IvyPanda. Saudi Food Industry’s Overview and Market Size Research Paper. 2022. Available online: https://ivypanda.com/essays/saudi-food-industrys-overview-and-market-size/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Baig, M.B.; Alotaibi, B.A.; Alzahrani, K.; Pearson, D.; Alshammari, G.M.; Shah, A.A. Food Waste in Saudi Arabia: Causes, Consequences, and Combating Measures. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Export. Saudi Arabia Country Profile. 2023. Available online: https://www.foodexport.org/export-insights/market-and-country-profiles/saudi-arabia-country-profile (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Kwon, D.Y. What is ethnic food? J. Ethn. Foods 2015, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.B.; Al-Zahrani, K.H.; Schneider, F.; Straquadine, G.S.; Mourad, M. Food waste posing a serious threat to sustainability in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—A systematic review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaquinto, A. Sustainable Practices among Independently Owned Restaurants in Japan. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2014, 17, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederle, P.; Schubert, M.N. HOW does veganism contribute to shape sustainable food systems? Practices, meanings and identities of vegan restaurants in Porto Alegre, Brazil. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 78, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J. Environmental sustainability management in the foodservice industry: Understanding the antecedents and consequences. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2016, 19, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J.; Zheng, T. Assessment of the environmental sustainability of restaurants in the U.S.: The effects of restaurant characteristics on environmental sustainability performance. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2020, 23, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destination KSA. The Green Revolution: Azka Farms. 2023. Available online: https://destinationksa.com/the-green-revolution-azka-farms/ (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Arab News. What We Are Buying Today: Azka Farms. 2023. Available online: https://www.arabnews.com/node/1755971/lifestyle (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Cho, M.; Yoo, J.J. Customer pressure and restaurant employee green creative behavior: Serial mediation effects of restaurant ethical standards and employee green passion. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 4505–4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raab, C.; Baloglu, S.; Chen, Y. Restaurant Managers’ Adoption of Sustainable Practices: An Application of Institutional Theory and Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2018, 21, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, A.; Ismail, A. Environmentally friendly practices among restaurants: Drivers and barriers to change. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 551–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, A.H.; Hassan, T.H.; Salem, A.E.; Elsaied, M.A.; Elsaed, A.A. Determinants and Consequences of Green Investment in the Saudi Arabian Hotel Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, H.; Nebioğlu, O.; Demirağ, M. A comparative study for green management practices in Rome and Alanya restaurants from managerial perspectives. J. Tour. Gastron. Stud. 2015, 3, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Saengchai, S.; Jermsittiparsert, K. The effect of supply chain and organizational culture on adoption of green practices by restaurants and hotels of Thailand. Int. J. Innov. 2020, 11, 743–764. [Google Scholar]

- Myung, E.; McClaren, A.; Li, L. Environmentally related research in scholarly hospitality journals: Current status and future opportunities. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1264–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maye, D.; Duncan, J. Understanding Sustainable Food System Transitions: Practice, Assessment and Governance. Sociol. Rural. 2017, 57, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A. Sustainable Food Practices: Choices & Importance. 2021. Available online: https://www.highspeedtraining.co.uk/hub/what-is-food-sustainability/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- March, J. Sustainable Food Practices. 2021. Available online: https://environment.co/sustainable-food-practices/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Perramon, J.; Alonso-Almeida, M.d.M.; Llach, J.; Bagur-Femenías, L. Green practices in restaurants: Impact on firm performance. Oper. Manag. Res. 2014, 7, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blay-Palmer, A. Imagining Sustainable Food Systems: Theory and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Khachatryan, S. Restaurants and Social Responsibility: The Future of Sustainability in the Industry. 2023. Available online: https://orders.co/blog/restaurants-and-social-responsibility-the-future-of-sustainability-in-the-industry/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Iberdrola. What Is Sustainable Food? Food Sustainability, A Recipe against Pollution. 2023. Available online: https://www.iberdrola.com/sustainability/sustainable-nutrition (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Filimonau, V.; Krivcova, M. Restaurant menu design and more responsible consumer food choice: An exploratory study of managerial perceptions. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kfouri, T.; Fernandes, A.C.; Bernardo, G.L.; Proença, L.C.; Uggioni, P.L.; Rodrigues, V.M.; Pacheco da Costa Proença, R. Sustainable solid waste management in restaurants: The case of the Ecozinha Institute, Brazil. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 27, 100464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Coşkun, A.; Derqui, B.; Matute, J. Restaurant management and food waste reduction: Factors affecting attitudes and intentions in restaurants of Spain. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 1177–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, M.; Fulton, L.; Schmutz, B. Green Cities and Waste Management: The Restaurant Industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, L.; Huang, Y.; Hu, L. Green attributes of restaurants: What really matters to consumers? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisch, L.; Eberle, U.; Lorek, S. Sustainable food consumption: An overview of contemporary issues and policies. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2013, 9, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Wahid, N.; Goh, Y. Perceived Drivers Of Green Practices Adoption: A Conceptual Framework. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2013, 29, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, G.; Klosse, P. Sustainable restaurants: A research agenda. Res. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 6, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanaguli, A.; Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Srivastava, S.; Singh, G. Environmental sustainability in restaurants. A systematic review and future research agenda on restaurant adoption of green practices. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 22, 303–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso, S. Comparing Voluntary Policy Instruments for Sustainable Tourism: The Experience of the Spanish Hotel Sector. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.W.; Wong, K.K.F.; Lo, J.Y. Environmental Quality Index for the Hong Kong Hotel Sector. Tour. Econ. Bus. Financ. Tour. Recreat. 2008, 14, 857–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Khan, M.A.S.; Anwar, F.; Shahzad, F.; Adu, D.; Murad, M. Green Innovation Practices and Its Impacts on Environmental and Organizational Performance. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 553625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawley, M.; Birch, D.; Craig, J. Managing sustainability in the seafood supply chain: The confused or ambivalent consumer. In A Stakeholder Approach to Managing Food; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 316–328. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.; Choon Tan, K.; Hanim Mohamad Zailani, S.; Jayaraman, V. Supply chain drivers that foster the development of green initiatives in an emerging economy. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2013, 33, 656–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzschentke, N.; Kirk, D.; Lynch, P.A. Reasons for going green in serviced accommodation establishments. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2004, 16, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, D.D.C.; Zandonadi, R.P.; Nakano, E.Y.; Botelho, R.B.A. Sustainability Indicators in Restaurants: The Development of a Checklist. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Lee, Y.; Tsai, C. Developing green management standards for restaurants: An application of green supply chain management. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, D.; Vidigal, M.; Farage, P.; Zandonadi, R.; Nakano, E.; Botelho, R. Environmental, Social and Economic Sustainability Indicators Applied to Food Services: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Rios, C.; Demen-Meier, C.; Gössling, S.; Cornuz, C. Food waste management innovations in the foodservice industry. Waste Manag. 2018, 79, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, A.H.; Hassan, T.H.; El Dief, M.M. A Description of Green Hotel Practices and Their Role in Achieving Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namkung, Y.; Jang, S. Effects of restaurant green practices on brand equity formation: Do green practices really matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Băltescu, C.A.; Neacșu, N.A.; Madar, A.; Boșcor, D.; Zamfirache, A. Sustainable Development Practices of Restaurants in Romania and Changes during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantele, S.; Cassia, F. Sustainability implementation in restaurants: A comprehensive model of drivers, barriers, and competitiveness-mediated effects on firm performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagur-Femenías, L.; Martí, J.; Rocafort, A. Impact of sustainable management policies on tourism companies’ performance: The case of the metropolitan region of Madrid. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J.; Zheng, T.; Bosselman, R. Top managers’ environmental values, leadership, and stakeholder engagement in promoting environmental sustainability in the restaurant industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 63, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, S. Financial Rewards for Social Responsibility: A Mixed Picture for Restaurant Companies. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 2009, 50, 168. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, J.; Hsieh, C. The Impact of Restaurants’ Green Supply Chain Practices on Firm Performance. Sustainability 2016, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsetoohy, O.; Ayoun, B.; Abou-Kamar, M. COVID-19 Pandemic Is a Wake-Up Call for Sustainable Local Food Supply Chains: Evidence from Green Restaurants in the USA. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namkung, Y.; Jang, S. Are Consumers Willing to Pay More for Green Practices at Restaurants? J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2017, 41, 329–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, A.; McKenzie, K.; Osobajo, O.; Lawani, A. Effects of millennials willingness to pay on buying behaviour at ethical and socially responsible restaurants: Serial mediation analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 113, 103507. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamogosa, H.M.; Obonyo, G.O. Sustainable Business Strategies For Fast-Food Restaurant Growth: Fast-Food Restaurant Managers’ Perspectives In Lake Region Economic Block, Kenya. J. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.; Jang, S.; Day, J.; Ha, S. The impact of eco-friendly practices on green image and customer attitudes: An investigation in a café setting. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 41, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Kim, W.; Kwon, J. Understanding the relationship between green restaurant certification programs and a green restaurant image: The case of TripAdvisor reviews. Kybernetes 2021, 50, 1689–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha’ari, N.S.M.; Sazali, U.S.; Zolkipli, A.T.; Vargas, R.Q.; Shafie, F.A. Environmental assessment of casual dining restaurants in urban and suburban areas of peninsular Malaysia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, N.H.; Kaida, N.; Othman, N.A.; Akhir, F.N.M.; Hara, H. Reducing Food Waste: Strategies for Household Waste Management to Minimize the Impact of Climate Change and Contribute to Malaysia’s Sustainable Development. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 479, 12035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkucuk, U. Food Loss and Waste: A Sustainable Supply Chain Perspective. In Disruptive Technologies and Eco-Innovation for Sustainable Development; IGI Global: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 90–108. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.S.; Jai, T. Waste less, enjoy more: Forming a messaging campaign and reducing food waste in restaurants. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 19, 495–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E.M. Restaurant Industry Sustainability: Barriers and Solutions to Sustainable Practice Indicators; Arizona State University: Tempe, AZ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeir, I.; Weijters, B.; De Houwer, J.; Geuens, M.; Slabbinck, H.; Spruyt, A.; Van Kerckhove, A.; Van Lippevelde, W.; De Steur, H.; Verbeke, W. Environmentally Sustainable Food Consumption: A Review and Research Agenda From a Goal-Directed Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. Saudi Arabian Food: 30 Classic and Traditional Foods to Savour. Available online: https://www.lacademie.com/saudi-arabian-food-guide/ (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Fernando, Y.; Halili, M.; Tseng, M.; Tseng, J.W.; Lim, M.K. Sustainable social supply chain practices and firm social performance: Framework and empirical evidence. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 32, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseman, M.G.; Joung, H.; Choi, E.; Kim, H. The effects of restaurant nutrition menu labelling on college students’ healthy eating behaviours. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datey, R.; Acharya, S.; Tiwari, K. The Impact Of Corporate Social Responsibility On Consumer Behaviour In The Restaurant Industry Of Indore. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 4, 177–191. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, J.; Moon, J.; Lee, W.S.; Chung, N. The Impact of CSR on Corporate Value of Restaurant Businesses Using Triple Bottom Line Theory. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.d.M.; Bagur-Femenias, L.; Llach, J.; Perramon, J. Sustainability in small tourist businesses: The link between initiatives and performance. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chițimiea, A.; Minciu, M.; Manta, A.; Ciocoiu, C.N.; Veith, C. The Drivers of Green Investment: A Bibliometric and Systematic Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, Y.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Wah, W. Pursuing green growth in technology firms through the connections between environmental innovation and sustainable business performance: Does service capability matter? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ch’ng, P.; Cheah, J.; Amran, A. Eco-innovation practices and sustainable business performance: The moderating effect of market turbulence in the Malaysian technology industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomsma, A. Systems under indirect observation: Causality, structure, prediction. In The Robustness of Lisrel against Small Sample Sizes in Factor Analysis Models; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1982; pp. 149–173. [Google Scholar]

- Nancarrow, C.; Brace, I.; Wright, L.T. Tell me Lies, Tell me Sweet Little Lies: Dealing with Socially Desirable Responses in Market Research. Mark. Rev. 2001, 2, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, D.M.; Fernandes, M.F. The Social Desirability Response Bias in Ethics Research. J. Bus. Ethics 1991, 10, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.L.; Clancy, K.J. Some Effects of “Social Desirability” in Survey Studies. Am. J. Sociol. 1972, 77, 921–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N. Detecting Multicollinearity in Regression Analysis. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2020, 8, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagelkerke, N.J.D. A note on a general definition of the coefficient of determination. Biometrika 1991, 78, 691–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmiento, C.V.; El Hanandeh, A. Customers’ perceptions and expectations of environmentally sustainable restaurant and the development of green index: The case of the Gold Coast, Australia. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 15, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrigot, R.; Watson, A.; Dada, O. Sustainability and green practices: The role of stakeholder power in fast-food franchise chains. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 3442–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latip, M.; Sharkawi, I.; Mohamed, Z.; Kasron, N. The Impact of External Stakeholders’ Pressures on the Intention to Adopt Environmental Management Practices and the Moderating Effects of Firm Size. J. Small Bus. Strategy 2022, 32, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. A Sustainable Saudi Vision. 2023. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/v2030/a-sustainable-saudi-vision/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Mai, K.N.; Nhan, D.H.; Nguyen, P.T.M. Empirical Study of Green Practices Fostering Customers’ Willingness to Consume via Customer Behaviors: The Case of Green Restaurants in Ho Chi Minh City of Vietnam. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulaessa, N.; Lin, L. How Do Proactive Environmental Strategies Affect Green Innovation? The Moderating Role of Environmental Regulations and Firm Performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, N.M. Estimation of Motives for Adopting Green Practices in Restaurants in Alexandria. J. Assoc. Arab. Univ. Tour. Hosp. 2017, 14, 140–148. [Google Scholar]

- Baloglu, S.; Raab, C.; Malek, K. Organizational Motivations for Green Practices in Casual Restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2022, 23, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Dief, M.; Font, X. Determinants of Environmental Management in the Red Sea Hotels. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2012, 36, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbeau, C.; Oelbermann, M.; Karagatzides, J.; Tsuji, L. Sustainable Agriculture and Climate Change: Producing Potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.) and Bush Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) for Improved Food Security and Resilience in a Canadian Subarctic First Nations Community. Sustainability 2015, 7, 5664–5681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moruzzi, R.; Sirieix, L. Paradoxes of sustainable food and consumer coping strategies: A comparative study in France and Italy. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ghadimi, P.; Lim, M.K.; Tseng, M. A literature review of sustainable consumption and production: A comparative analysis in developed and developing economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelle, U. Combining qualitative and quantitative methods in research practice: Purposes and advantages. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, T. Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches: Some Arguments for Mixed Methods Research. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2012, 56, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, F.; Nasir, N. Impact of green human resource management practices on sustainable performance: Serial mediation of green intellectual capital and green behaviour. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Gelaidan, H.M.; Shah, S.H.A.; Amjad, R. Green transformational leadership and green creativity? The mediating role of green thinking and green organizational identity in SMEs. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 977998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahrani, A.A. Team Creativity and Green Human Resource Management Practices’ Mediating Roles in Organizational Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 221 | 100 |

| Female | - | - |

| Age | ||

| From 30 to 40 years old | 65 | 29.4 |

| From 41 to 50 years old | 138 | 62.4 |

| More than 50 years old | 18 | 8.2 |

| Educational level | ||

| University degree | 156 | 70.6 |

| Master degree | 54 | 24.4 |

| Doctorate | 11 | 5 |

| Current position | ||

| Restaurant manager | 194 | 87.8 |

| Restaurant owner | 27 | 12.2 |

| Length of implementing SFPs in the restaurant | ||

| Less than 1 year | 28 | 12.7 |

| From 1 to 3 years | 144 | 65.2 |

| More than 3 to 5 years | 37 | 16.7 |

| More than 5 years | 12 | 5.4 |

| Total | 221 | 100% |

| Construct | Item | Outer Loading | α1 | CR2 | AVE3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customers’ and stakeholders’ sustainable behaviors (C&SSB) | C&SSB1 | 0.855 *** | 0.889 | 0.938 | 0.717 |

| C%SSB2 | 0.809 *** | ||||

| C&SSB3 | 0.889 *** | ||||

| C&SSB4 | 0.842 *** | ||||

| C&SSB5 | 0.852 *** | ||||

| C&SSB6 | 0.831 *** | ||||

| Governmental laws and regulations around sustainability (G&LR) | GL&R1 | 0.910 *** | 0.864 | 0.919 | 0.791 |

| GL&R2 | 0.885 *** | ||||

| GL&R3 | 0.874 *** | ||||

| Commitment to combat climate change (CC) | CC1 | 0.868 *** | 0.781 | 0.842 | 0.727 |

| CC2 | 0.837 *** | ||||

| Financial and non-financial outcomes of adopting SFPs (F&NF) | F&NF1 | 0.832 *** | 0.766 | 0.803 | 0.670 |

| F&NF2 | 0.806 *** | ||||

| Restaurants’ values and culture toward sustainability (RV&C) | RV&C1 | 0.894 *** | 0.854 | 0.914 | 0.727 |

| RV&C2 | 0.795 *** | ||||

| RV&C3 | 0.822 *** | ||||

| RV&C4 | 0.896 *** | ||||

| Sustainable Food Practices (SFPs) | SFP1 | 0.901 *** | 0.917 | 0.973 | 0.785 |

| SFP2 | 0.835 *** | ||||

| SFP3 | 0.893 *** | ||||

| SFP4 | 0.914 *** | ||||

| SFP5 | 0.940 *** | ||||

| SFP6 | 0.911 *** | ||||

| SFP7 | 0.847 *** | ||||

| SFP8 | 0.887 *** | ||||

| SFP9 | 0.819 *** | ||||

| SFP10 | 0.903 *** | ||||

| Economic Performance (ECO) | ECO1 | 0.922 *** | 0.883 | 0.915 | 0.783 |

| ECO2 | 0.879 *** | ||||

| ECO3 | 0.852 *** | ||||

| Environmental Performance (ENVR) | ENVR1 | 0.917 *** | 0.901 | 0.946 | 0.814 |

| ENVR2 | 0.905 *** | ||||

| ENVR3 | 0.889 *** | ||||

| ENVR4 | 0.897 *** | ||||

| Social Performance (SOC) | SOC1 | 0.886 *** | 0.877 | 0.922 | 0.798 |

| SOC2 | 0.904 *** | ||||

| SOC3 | 0.889 *** |

| Construct | CC | C&SSB | ECO | ENVR | F&NF | GL&R | RV&C | SFPs | SOC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | 0.853 | ||||||||

| C&SSB | 0.408 | 0.847 | |||||||

| ECO | 0.432 | 0.550 | 0.885 | ||||||

| ENVR | 0.391 | 0.543 | 0.495 | 0.902 | |||||

| F&NF | 0.341 | 0.382 | 0.465 | 0.477 | 0.819 | ||||

| GL&R | 0.420 | 0.465 | 0.430 | 0.434 | 0.411 | 0.889 | |||

| RV&C | 0.396 | 0.590 | 0.521 | 0.414 | 0.423 | 0.328 | 0.853 | ||

| SFPs | 0.639 | 0.702 | 0.677 | 0.627 | 0.608 | 0.650 | 0.740 | 0.886 | |

| SOC | 0.365 | 0.504 | 0.482 | 0.761 | 0.474 | 0.408 | 0.391 | 0.591 | 0.893 |

| Construct | CC | C&SSB | ECO | ENVR | F&NF | GL&R | RV&C | SFPs | SOC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | |||||||||

| C&SSB | 0.408 | ||||||||

| ECO | 0.474 | 0.602 | |||||||

| ENVR | 0.444 | 0.616 | 0.613 | ||||||

| F&NF | 0.341 | 0.382 | 0.505 | 0.539 | |||||

| GL&R | 0.420 | 0.465 | 0.470 | 0.492 | 0.411 | ||||

| RV&C | 0.396 | 0.590 | 0.572 | 0.469 | 0.423 | 0.328 | |||

| SFPs | 0.690 | 0.720 | 0.778 | 0.748 | 0.649 | 0.695 | 0.776 | ||

| SOC | 0.414 | 0.571 | 0.597 | 0.810 | 0.537 | 0.463 | 0.443 | 0.705 |

| Construct | ECO | ENVR | SFP | SOC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | 1.373 | |||

| C&SSB | 1.794 | |||

| ECO | ||||

| ENVR | ||||

| F&NF | 1.379 | |||

| GL&R | 1.475 | |||

| RV&C | 1.696 | |||

| SFPs | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| SOC |

| Construct | R2 | Q2predict | f2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFPs | ECO | ENVR | SOC | |||

| CC | 0.533 | |||||

| C&SSB | 0.799 | |||||

| ECO | 0.458 | 0.429 | ||||

| ENVR | 0.394 | 0.377 | ||||

| F&NF | 0.358 | |||||

| GL&R | 0.415 | |||||

| RV&C | 0.595 | |||||

| SFPs | 0.937 | 0.935 | 0.844 | 0.649 | 0.536 | |

| SOC | 0.349 | 0.335 | ||||

| Hypothesized Path | Path Coefficient | T Statistics | Confidence Intervals | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5% | 97.5% | ||||

| H1: C&SSB → SFPs | 0.450 *** | 19.985 | 0.405 | 0.494 | Accepted |

| H2: GL&R → SFPs | 0.196 *** | 10.292 | 0.159 | 0.234 | Accepted |

| H3: CC → SFPs | 0.214 *** | 11.708 | 0.179 | 0.250 | Accepted |

| H4: F&NF → SFPs | 0.176 *** | 8.509 | 0.136 | 0.217 | Accepted |

| H5: RV&C → SFPs | 0.252 *** | 11.000 | 0.207 | 0.297 | Accepted |

| H6: SFPs → ECO | 0.677 *** | 20.823 | 0.610 | 0.737 | Accepted |

| H7: SFPs → ENVR | 0.627 *** | 17.078 | 0.554 | 0.697 | Accepted |

| H8: SFPs → SOC | 0.591 *** | 15.261 | 0.513 | 0.666 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdou, A.H.; Hassan, T.H.; Salem, A.E. Promoting Sustainable Food Practices in Food Service Industry: An Empirical Investigation on Saudi Arabian Restaurants. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612206

Abdou AH, Hassan TH, Salem AE. Promoting Sustainable Food Practices in Food Service Industry: An Empirical Investigation on Saudi Arabian Restaurants. Sustainability. 2023; 15(16):12206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612206

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdou, Ahmed Hassan, Thowayeb H. Hassan, and Amany E. Salem. 2023. "Promoting Sustainable Food Practices in Food Service Industry: An Empirical Investigation on Saudi Arabian Restaurants" Sustainability 15, no. 16: 12206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612206

APA StyleAbdou, A. H., Hassan, T. H., & Salem, A. E. (2023). Promoting Sustainable Food Practices in Food Service Industry: An Empirical Investigation on Saudi Arabian Restaurants. Sustainability, 15(16), 12206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612206