1. Background

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a major strategy to align China’s development with that of other countries along the routes while addressing different needs. In the autumn of 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping of the People’s Republic of China proposed the Belt and Road Initiative. The goal of the BRI is fivefold: (i) policy coordination; (ii) facilities connectivity; (iii) unimpeded trade; (iv) financial integration; and (v) people-to-people bonds. The Initiative aims to interconnect countries in Asia, Europe, and Africa through an ambitious vision for infrastructure, economic and political cooperation. The BRI has certainly garnered a lot of attention from the global community, and the response has been overwhelmingly positive. International organizations and scholars alike have recognized the potential benefits of the BRI, particularly when it comes to improving infrastructure, increasing investment, and driving economic growth, especially in low-income countries [

1,

2,

3]. It is clear that the BRI has the potential to be a game-changer, and it is exciting to see how it will continue to evolve in the coming years. Shichor [

4] reported that the Chinese leaders, including policymakers, were pleasantly surprised by the positive reception to President Xi Jinping’s proposal of the BRI just like other countries. In response, the Chinese Government committed USD 1 trillion for the initiative for ten (10) years (2013–2023). Yu, Li, Yang & Wei [

5] argue that the USD 1 trillion funding for the initiative over 10 years is insufficient given the massive scale of infrastructure needs in Asia and beyond. For instance, the Asian Development Bank estimates that the Asia-Pacific region alone will require USD 1.7 trillion annually in infrastructure investments until 2030 to maintain growth, alleviate poverty and respond to climate change [

6]. However, while the funding may not be sufficient to meet all infrastructure needs, the amount is still significant and can help finance much-needed projects in many developing countries especially in Africa.

After the commitment of USD 1 trillion, there was still a lack of clarity and coordination in the initiative’s implementation, which led to some confusion and skepticism from other countries like the USA. Thus, the issuance of a document titled “

Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road” by the National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China through the State Council on 28 March 2015 was a significant turning point for the BRI. The document aimed to promote the implementation of the Initiative, instill vigor and vitality into the ancient Silk Road, connect Asian, European, and African countries more closely, and promote mutually beneficial cooperation to a new high and in new forms [

7]. Only by working together can countries achieve sustainable development and create a brighter future for future generations. However, the [

2] cautioned against risks such as debt sustainability, corruption, and environmental degradation. The document provided a more detailed and comprehensive roadmap of implementing the BRI, and helped to allay some of the concerns and uncertainties that had been raised. The document also provided insights into the objectives, strategies, and challenges of the BRI, as well as the perspectives of different actors on this initiative.

By January 2023, 152 countries from Asia, Europe and Africa signed the Belt and Road Initiative MoU with China as compared to 142 countries in December 2021. It is worth noting that the Belt and Road Initiative initially focused on Asia and European countries before expanding to include African countries [

7,

8]. South Africa and Egypt were among the first African countries to sign the Belt and Road Initiative Memorandum of Understanding (MoU). This highlights China’s commitment to building closer partnerships and promoting high-quality cooperation with countries across the world. The BRI focused on connecting all 54 African countries through transportation infrastructure projects, including modern highways, airports, and high-speed railways. Furthermore, the Belt and Road Initiative aims to promote the connectivity of the Asian, European, and African continents and their adjacent seas, establish and strengthen partnerships among the countries along the Belt and Road, set up all-dimensional, multi-tiered, and composite connectivity networks, and realize diversified, independent, balanced, and sustainable development in these countries [

7]. Such partnerships can help promote sustainable development and prosperity for all involved.

The number of MoUs signed within a very short time indicates continued global interest and participation in the BRI, despite some criticisms and concerns. However, scholars and development partners (for example, [

1,

2,

5,

9,

10,

11,

12]) have raised concerns about the lack of transparency and potential negative impacts of BRI projects, including the risk of creating unsustainable debt burdens for participating countries. It is important to note that the number of countries signing the MoU does not necessarily indicate the level of success of BRI projects in each country. Therefore, further analysis and evaluation of the actual impact and outcomes of the BRI projects in each participating country are necessary to fully understand the initiative’s overall effectiveness, hence the justification of this study.

The BRI is expected to promote trade and strengthen economic growth across the region [

2,

13] leading to a 25% reduction in road transport margins and 5% in sea transport margins, and to coordinate economic policy and improve regional collaboration and contribute to lifting 7.6 million people from extreme poverty and 32 million from moderate poverty by 2030. It is interesting to note that the UN has acknowledged the intrinsic link between each of the five pillars of the BRI and the 17 SDGs 2030 Agenda [

14]. According to their report, China is interested in collaborating with other parties to promote high-quality BRI cooperation, with a focus on building closer partnerships for health cooperation, connectivity, green development, and openness and inclusiveness. This is a positive step towards a more sustainable and prosperous future for all involved. The connectivity projects of the BRI have the potential to tap the market potential in this region, promote investment and consumption, create demands and job opportunities, and enhance people-to-people and cultural exchanges. Moreover, these projects will enable the peoples of the relevant countries to understand, trust, and respect each other, and live in harmony, peace, and prosperity.

Despite these benefits, the BRI is perceived as a debt trap and a strategy by China to dominate the world. Ref. [

4] revealed that the BRI practically ignores a variety of obstacles and risks, such aspiracy, terrorism, Islamic extremism, ethnic and national rivalries, internal and interstate violence along the routes (both on land and sea). These challenges, if not addressed, may disrupt the movement of investments, goods, and people at unexpected times. Similarly, it is hard to find reliable data on the BRI [

15]. This is because it is difficult to distinguish a BRI project from regular economic or diplomatic relations. Hence, the BRI lacks a clear description, leaving the reader with different interpretations. It is against this background this study aimed: (a) to establish how the BRI is defined and provide an alternative definition; (b) to compare Africa–China relationships before and after the BRI; (c) to examine the benefits of the BRI using the “Five Connectivities” pillars; and (d) to identify the challenges the BRI is facing in Africa especially from the selected countries. The

Section 1 of the study presents the background of the study, followed by methods, results and discussions that are presented according to each objective, policy implications, conclusion and finally limitations and areas for future study.

2. Methods

This study was qualitative in nature with biased to case study research. Case study research is a valuable qualitative research method that involves thorough exploration and analysis of a specific/particular case, such as an organization, a program, or an event, in order to understand its unique characteristics and complexities. According to [

16], case study research is an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially the boundaries between the phenomenon and its context. Scholars such as [

16,

17,

18] considered case study research as a useful research strategy when the research topic is broad and highly complex, the context under investigation is essential, and there is not much theory available in the field. Case study research therefore involves several approaches such as single, multiple, descriptive, exploratory and explanatory cases [

16,

19,

20]. Despite the many approaches, this study used multiple case studies to identify the common themes and patterns and then to compare and contrast the BRI projects experience in five African countries such as Uganda, Kenya, Egypt, Djibouti, and Mozambique. The five countries were specifically selected for their early embracement of the Initiative and strategic location in the continent which gives each country a unique geographical advantage. For example, Egypt is strategically located at the intersection of Africa, Asia, and Europe, while Djibouti is a gateway to the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. Uganda and Kenya are located in East Africa, a key transportation hub for the region, while Mozambique is located in Southern Africa.

In order to answer the research questions, researchers adopted multiple data sources such as documents and archival records, especially the Policies, Projects, Initiatives and Strategies (PPIS), records of which were obtained from web-based/online platforms. The PPIS refers to the various plans, activities and programs implemented by governments or any other institutions to achieve specific objectives. The PPIS data included the government reports, organizational documents, and program evaluations. The PPIS source of data is widely available and accessible, and provides rich data which are reliable, versatile, and support longitudinal analysis. Other sources used direct observations and secondary data from published referred journals and surveys from reputable organizations. The data collected were then converged to strengthen the findings and give a greater understanding of the phenomenon. Scholars such as [

14,

17] contend that the use of multiple data sources in qualitative study enhances data credibility. The researchers also ensured rigor and trustworthiness by providing a detailed description of the research methods, data collection procedures, and data analysis techniques used in the study in order to ensure that the study is transparent and replicable. Furthermore, researchers used multiple data sources to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the topic under study. The research underwent peer review and panel discussion at the 7th Global Research Network–Belt and Road Initiative Conference 2023, which took place from 7–9 February 2023, at the University of Nairobi. During the conference, the researchers presented their paper. The feedback obtained was incorporated in the study which makes the findings transparent and confirmable.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. BRI Defined

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was initially referred to as One Road, One Belt (OBOR). The concept has two main components: the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. The Silk Road Economic Belt focuses on improving connectivity and infrastructure development through Central Asia, Russia, and Europe. In contrast, the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road focuses on developing maritime routes and ports in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. In 2017, during the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation held in Beijing, China. President Xi Jinping described the BRI as “

a project of the century” and “

a new form of globalization” [

8]. Below are some of the scholarly and practitioners’ understanding of the BRI [

7,

21,

22,

23] (

Table 1):

It is difficult to define the BRI concept because of its dynamics. For instance, supporters view it enthusiastically as a means of promoting global economic growth and development. At the same time critics consider it with skepticism because they look at it as a debt trap and strategies the Chinese Government employs to dominate developing countries. However, the most used and widely accepted definition of the BRI is by the [

7] which refers to an ambitious economic vision of the opening-up of and cooperation between the Asian, European, and African continents in order to promote economic prosperity and regional economic cooperation through strengthening exchanges and mutual learning between different civilizations, and promote world peace and development. From the above definitions, the researchers defined the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) “

as an ambitious economic vision that aims to promote regional economic cooperation and mutual learning between different civilizations across Asia, Europe and Africa continents”. To achieve this, the initiative strengthens exchanges and cooperation between participating countries, fosters a more interconnected world, and promotes world peace and development. To scientifically test the concept of the BRI, researchers have proposed five measuring constructs which include:

- (a)

Infrastructure development: This includes the construction of ports, airports, railways, highways, and other forms of infrastructure that improve connectivity among participating countries, and the indicators include quantity of infrastructures completed, quality of infrastructures, impact on local economies, time taken to complete the work, and job creation.

- (b)

Trade and investment: This dimension aims to promote trade and investment between participating countries, and indicators could include the increase in trade volumes, the number of new businesses established, free trade agreements, and the amount of foreign direct investment attracted.

- (c)

Economic growth: The dimension aims to promote economic growth and development, and indicators could include GDP growth rates, job creation, and poverty reduction.

- (d)

People-to-people exchanges: The dimension aims to promote cultural and educational exchanges among participating countries, and indicators could include the number of student and cultural exchanges, joint research projects, stimulus to innovation, think tank cooperation, and the number of tourist arrivals.

- (e)

Environmental sustainability: The dimension aims to promote environmental sustainability and indicators could include the reduction in carbon emissions, adopting renewable energy, and conserving natural resources.

One way to measure the effectiveness of infrastructure development in BRI projects is by examining the above indicators. These indicators can help assess the success of investments in modern highways, airports, high-speed railways, bridges, oil pipeline, ports, power generation (hydropower), and industrial parks. Such development has the potentials to promote connectivity and stimulate economic growth within the country.

3.2. BRI Development in Africa

Before the roll-out of the BRI in Africa, China had deep roots in most African countries after their independence, with the BRI being a transcontinental development aimed at connectivity among nations in Asia, Europe, and Africa [

24]. At least 52 African countries including the African Union signed the MoU for the project with the exception of Eritrea, Libya, Somalia, and South Sudan. The main driver was political and economic factors for both groups of countries (signed and not signed). Those that signed looked at the BRI as opportunity for them to complement their infrastructural gaps, increase foreign investment, expand trade, and reduce poverty, while the others were uncertain of the implications of the BRI. Here are the cases of the five selected countries that signed the BRI MoU and have had a substantial experience with BRI projects.

3.2.1. Uganda Case

The relationship between Uganda and the People’s Republic of China has been a strong and mutually beneficial one since 1962. One of the ways in which the two countries are strengthening their relationships is through the BRI. However, some national and international political analysts have criticized this close relationship, arguing that it could potentially undermine US interests in Uganda, given the differing priorities of the two countries [

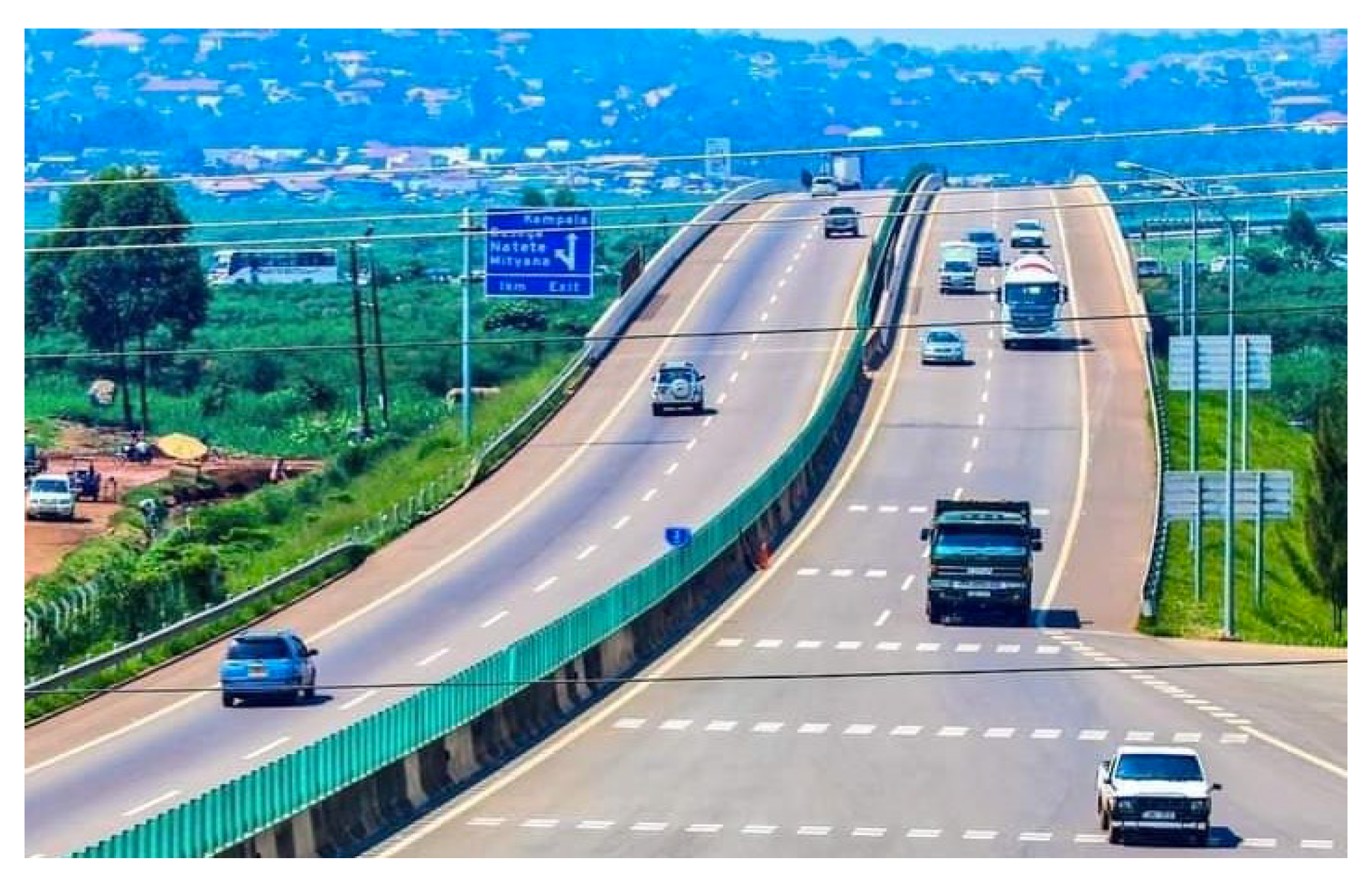

25]. With Chinese financing several of country’s infrastructural development through the BRI, the construction of the Kampala-Entebbe Expressway, Karuma and Isimba hydropower dams as well as the ongoing expansion of the Entebbe International Airport really possess threats to US. For example, the 49.56 km Expressway worth USD 479.2 million (with 74% of the cost from loans) started in 2012 and was completed in 2019 and is now the first toll fee road in Uganda. The work was carried out by the China Communications Construction Company Ltd. and supervised by Beijing Expressway Supervision Company Ltd. These projects have improved connectivity within Uganda in terms of improved traffic conditions on both bypass and distributor roads in urban areas, as well as enhancing urban development and improving connectivity between Uganda and other countries in the region, and have contributed to the country’s economic development.

Currently, China is one of Uganda’s largest trading partners along with India, Kenya, and the European Union [

26]. Uganda and the People’s Republic of China have signed multiple agreements to boost trade and investment between them. Chinese entrepreneurs have set up six industrial parks in Uganda with the support of the Ugandan Government. The industrial parks include the Shandong Industrial Park in Luzira, Tiantang Industrial Park in Mukono, Liaoshen Industrial Park in Kapeeka, Uganda-China (Guangdong) Free Zone of International Co-operation in Sukulu, Mbale Industrial Park, and Kehong Agricultural Industrial Park in Luweero. These companies have helped the country to diversify its economy since they stimulate manufacturing, agriculture, and tourism. They have also contributed to job creation and economic growth in the country; promoted cultural and people-to-people exchanges, through initiatives such as the Confucius Institute at Makerere University and scholarships for Ugandan students to study in China as well as the teaching of Chinese language in some Secondary Schools; and strengthened mutual understanding between the two countries.

Despite the benefits BRI projects have brought to the country, there are concerns about the negative impacts on the environment and society, as well as lack of public consultation and accountability, and mismanagement of funds [

27]. The Center for Global Development [

28] also argued that many of the projects funded by China in Uganda are expensive and not economically viable. While these projects can offer valuable benefits, it is crucial to address these issues and manage them properly to minimize any potential harm to our communities and surroundings. Those responsible for such projects should be held accountable, with the well-being of our people and planet as their top priority. It is important to note that the Government has demonstrated its commitment to debt management; for instance, in 2020 the Government successfully renegotiated the loan for the Kampala-Entebbe Expressway in terms of interest rates and repayment period. Through the Ministry of Finance Planning and Economic Development (MoFPED), the Government launched a Mid-Term Debt Management Strategy March 2022–June 2025. The purpose of the strategy is to strengthen debt management practices and ensure sustainable borrowing [

29]. The Strategy address the issues of increasing revenue mobilization, diversifying sources of financing, improving debt transparency and monitoring. Below is an Illustration of some completed BRI projects in Uganda.

3.2.2. Kenya Case

Diplomatic relations between Kenya and China started in late 1963 after Kenya gained independence from British colonial rule. The China-Kenya relationship has been focused on development assistance, investment, and technical support for Kenya over the years. Recently, China has deepened its strategic and diplomatic ties with Kenya due to its important infrastructure and trade connectivity in East Africa and the wider African continent. For example, the World Bank indicated that China is one of the major trading partners for Kenya [

30]. In contrary, some members of the public especially from the Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) argued that such influence could compromise Kenya’s sovereignty and political independence [

31] and consequently will lead to long term economic risks and dependency on Chinese financing [

32]. It is important to consider these concerns and weight them against the potential benefits of closer ties with China in terms of infrastructure and trade connectivity. Today, the BRI with its focus on policy coordination, facilities connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and people-to-people bonds is playing a key role in this relationship. The Chinese Government through the BRI constructed the Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway (SGR); the first railway in Kenya since its independence in 1963. The 472 km long railway cost about USD 3.8 billion (90% of which was funded by Chinese loans). The project started in 2014 and was completed in 2017 and is now operational.

The construction was carried out by China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) under the supervision of Bridge Corporation and China Communications Construction Company (CCCCC). Other notable projects under the BRI were Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor, Nairobi Expressway, Likoni Floating Bridge, and the Makupa Bridge. These projects had had a positive impact on the economy of Kenya; for example, the SGR has significantly reduced transportation costs and time for goods and people, resulting in an economic growth in the country. The companies such as CCCC and CRBC also provided technical assistance and training to Kenyan engineers and workers to build local capacity, created over 46,000 jobs for local people, enhanced bilateral economic and trade development, and advanced cultural exchanges between China and Kenya. It is important to acknowledge that while the BRI has brought about many positive changes in Kenya, there have also been reports of poor working conditions and labor abuses such forced labor and inadequate compensation for workers [

33], as well as concerns about increasing debts which could potentially leading to macroeconomic instability [

34]. Other related challenges were environmental injustice which was associated with the destruction of animal and bird habitats, and corruption associated with lack of transparency in the procurement of these projects. Park and Kim [

35] and [

5,

36], argued that the Government of Kenya did not involve local communities and civil society groups in the planning and implementation of the SGR and other related BRI projects. It is crucial that all stakeholders involved in these projects work together to address these challenges and ensure that they do not overshadow the positive impact that these developments have had on the economy and the lives of people in Kenya.

The Kenya Government has demonstrated the ability to manage its debts; for instance, the Government has diversified its sources of financing by issuing Eurobonds and other securities on international capital markets to raise funds. According to the IMF, Kenya’s external borrowing strategy aims to maintain a balance between concessional and non-concessional financing, and between bilateral and multilateral financing [

37]. The Government is also implementing the Public Financial Management Reforms Strategy 2018–2023. World Bank [

30] contends that the reforms aimed to improve efficiency and transparency in the use of public resources. Other strategies adopted by the government are renegotiating the loan terms, enhancing revenue collections by implementing the Kenya Tax Policy 2021, and prioritizing debt repayment in order to reduce its debt burden and improve its creditworthiness. Below is an illustration of some completed BRI projects in Kenya.

3.2.3. Egypt Case

The diplomatic relationship between Egypt and China was forged in 1956 after the 1952 Egyptian Revolution. There have been frequent high-level visits and cooperation between the two countries on various political, economic, and cultural issues. Egypt was the first country in the continent to sign the BRI MoU in 2013, and China has since become a major investor in Egypt. They have invested heavily in infrastructure projects such as the construction of a New Administrative Capital City and the development of the Suez Canal Economic Zone (SCZone) which is a major economic development project aimed at creating a world-class industrial and logistics hub around the Suez Canal. The SCZone covers an area of over 461 square kilometers and includes six ports, as well as various industrial, commercial, and residential zones. With Egypt having two mega multi-billion dollar loans from China, detailed analysis will be limited to the New Administrative Capital City, whose construction began in 2015 and is still ongoing. The project is being carried out in phases, with the first phase including the construction of government buildings, residential areas, and infrastructure such as roads, water and sewage systems, and public transportation. The goal of the new administrative capital is to relieve congestion in Cairo, Egypt’s current capital, and to provide a modern, sustainable city with state-of-the-art infrastructure and amenities [

38] The project is expected to be inaugurated in 2030, but due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused some delays (like the movement of personnel and resources from China as a result of travel bans) this may take at least two more years.

Although the construction will take time, Egypt will have the Tallest Tower in Africa (a 385 m high skyscraper with 80 floors) that showcases smart and sustainable city principles. A consortium of companies, such as the China State Construction Engineering Corporation (CSCEC) and the Arab Contractors (a local construction company) are involved which is being supervised by Egyptian Government Entities (EGEs) such as the New Urban Communities Authority (NUCA) and the Administrative Capital for Urban Development (ACUD) company, together with other Egyptian consulting firms and the public. These entities ensure that the project meets the government’s objectives and adheres to its vision of creating a modern and sustainable capital city. Since the project involved large tracts of land, the acquisition process took a long time especially in areas with existing settlements, while there have been some concerns in coordinating and managing multiple contractors, consultants, and government entities, which affects the decision-making process in terms of quality control and project timeline. From the available sources, the citizens are not speaking out against the project like in other countries which is a sign that the citizens seem to support the projects (Government strategic directions). However, the [

39], cautioned the Government on sustainability and transparency of some of the BRI projects especially on debt burden and economic challenges. Below is an illustration of some completed BRI projects in Egypt.

BRI New Administrative Capital City of Egypt at a Glance (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6):

3.2.4. Djibouti Case

Djibouti established diplomatic relations with China in 1979, when China opened up to the world. Over the years, the two countries have managed to uphold a cordial and collaborative relationships in various aspects such as politics, economy, trade, culture, and education. In recent years, China has become more involved in Djibouti’s economic development and infrastructure projects, including the construction of a new port and a railway connecting Djibouti to Ethiopia, which are part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative [

40], Additionally, Djibouti is home to China’s first overseas military base, established in 2017, [

41], reflecting the growing strategic importance of Djibouti to China’s interests in the country and Africa.

The game-changer projects have been, for example, the construction of Doraleh Multipurpose Port which started in 2004 and was completed in 2017, by China State Construction Engineering Corporation (CSCEC) and under the supervision of CCCC Fourth Harbor Engineering Co., Ltd, and the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway construction of which began in 2011 and which was completed in 2016. The railway project was constructed by China Railway Engineering Corporation (CREC) and China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC) and supervised by the China Railway Seventh Group Co., Ltd., [

42]. The expansion of Djibouti’s international airport project started in 2015 and was completed in 2018, the contract for which was awarded to the China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC) and the supervision was carried out by the China Airport Construction Group Corporation (CACG).

The BRI projects in Djibouti have significantly impacted the country’s infrastructure and economy. The projects have provided Djibouti with improved transportation and trade links and stimulated economic growth and job opportunities and enhanced the country’s position as a regional hub for trade and transportation. These projects align with Africa’s 2063 vision of establishing an integrated railway network, connecting the continent from Egypt in the north to South Africa in the South. However, there are concerns about the high levels of debt incurred by Djibouti to finance these projects, the environmental impact of these developments, and lack of transparency, disregard of community concerns, and threats of environmental degradation [

43]. Furthermore, in the Financial Times [

41,

44], some experts warn that Djibouti’s debt to China could become unsustainable and potentially force the country to default on its loans, which could result in China taking control of its assets, including its strategically important ports. It is essential for all parties involved to collaborate and ensure that the projects are sustainable and advantageous for everyone. On the other hand, the country is using several strategies such as renegotiating loan terms, seeking debt relief, and diversifying its sources of funding as well as seeking investments from other countries (like the United States, France, and Japan) and multilateral institutions (such as the World Bank and the African Development Bank) in order to pay its debts [

45]. These efforts have already shown some success, such as renegotiating the terms of its loan for the Doraleh Multipurpose Port, from 8.5% to 3% interest rate, and extending the loan repayment period from 10 to 25 years. Below is an illustration of some completed BRI projects in Djibouti.

BRI Completed Selected Projects in Djibouti at a Glance (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8):

3.2.5. Mozambique Case

Mozambique has had diplomatic relations with China since 1975 when Mozambique gained independence from Portugal. Over the years, the two countries have strengthened their relationship through various initiatives, including trade and investment, infrastructure development, and cultural exchanges [

47], China has become a major economic partner for Mozambique, with Chinese companies investing heavily in Mozambique’s natural resources sector, particularly in coal and gas. In recent years, China has provided substantial development assistance to Mozambique, with China financing several infrastructure projects in the country, including roads, bridges, ports, and airports. The Maputo-Katembe Bridge was an impressive undertaking, spanning the Maputo Bay and becoming the longest suspension bridge on the African continent, measuring 680 m [

48]. The project was financed and built by China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) at a cost of USD 785 million, by a Chinese state-owned company and supervised by German engineering firm Gauff. The project started in 2014 and was inaugurated in November 2018, with the project Manager/Supervisor ensuring that the project was completed on time, within budget, and to the required standards. Gauff also provided technical expertise and advice throughout the construction process. Other BRI projects include Nacala Corridor Railway and Port, Thermal Power Plant in Maputo, and Natural Gas Processing Plant in Palma, among other projects financed by Chinese loans.

It is important to note that the bridge has been hailed as a major achievement for Mozambique and a symbol of the close ties between the two countries. The China–Mozambique bilateral cooperation has deepened and strengthening economic resilience and boosting market confidence, while also providing skills training opportunities for thousands of local employees. The projects have also played a part in boosting the country’s economic growth and development. However, there are valid concerns about transparency, accountability, increasing debts, and environmental hazards associated with these projects. For example, in 2018 the Mozambican Centre for Public Integrity raised questions about the procurement process for the construction of a new airport in Nacala, which was awarded to a Chinese company without a competitive bidding process. Despite the challenges, the Mozambique Government have developed several strategies to increase transparency and accountability, manage debts, and address environmental injustice in these projects. The Government has established a national agency to oversee and manage public-private partnerships and infrastructure projects, diversified its sources of financing for infrastructure projects, and aligned the BRI projects with its national development priorities in order to contribute to sustainable economic growth. Below is an Illustration of some completed BRI projects in Mozambique.

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Africa–China Relationships before and after BRI

The relationship between Africa and China has undergone significant changes over the years, with the BRI playing a significant role in sustaining it.

Table 2 shows a comparative analysis of Africa–China relationships before and after the BRI.

Before the launch of the BRI in 2013, China had already established itself as a significant player in Africa’s economic and political landscape. China had been investing in Africa since the 1960s, primarily in infrastructure development, natural resource extraction, and trade. However, the relationship was largely one-sided, with China benefiting more from the relationship than the African continent. With the initiative, there has been increased investment, trade, and infrastructure development between the two sides. Infrastructure development projects such as ports, railways, and roads have been a major focus of China’s investment in Africa. The BRI has also facilitated the establishment of new economic zones and the expansion of existing ones in Africa, boosting the continent’s economic growth. The impact of the BRI on African countries has been both positive and negative, for instance, some countries have benefited significantly from increased investment and infrastructure development (for instance, Egypt, Mozambique and Kenya) while others have fallen into debt traps, like Djibouti whose loans’ value is higher than the country’s GDP, and has led to increased Chinese influence in Africa. The BRI has marked a shift in China’s strategy towards Africa, that is, from merely extracting resources and conducting trade, to investing in long-term projects that have a significant impact on Africa’s economic growth.

From the above analysis, it is important to note that there is consensus from all countries under the initiative that the BRI has had a number of benefits [

7,

9,

21,

31,

35,

49,

50,

51] and these include (

Table 3):

From the above, the BRI is a real economic changer for African countries in the areas of economic growth and development. It has facilitated cooperation and exchange in a variety of areas between and among other countries in the continent. Researchers such as [

7,

9,

49,

50,

51,

52] and contend with the findings that BRI has promoted economic growth, industrialization, and intra-regional trade and created new markets for African goods, especially in African countries such as Uganda, Kenya, Djibouti, and Egypt which had significant infrastructure deficits. Furthermore, Yang, [

50] adds that the BRI has helped African countries to diversify their economies and reduced their dependence on commodity exports. While this study analyzed the short-term benefits of BRI projects in the selected countries in Africa, there is a need for more research on the long-term impact of these projects on economic development, social welfare, and environmental sustainability.

3.4. Challenges of the BRI Implementations

The major challenges identified in the BRI project implementations from the five selected countries are discussed below:

Low/lack of involvement of local stakeholders: The implementation of BRI projects often involves a few government representatives, Chinese companies, and workers, with limited local participation. Unfortunately, this lack of involvement of local communities and leaders in decision-making processes can lead to conflicts over land compensation and resettlement as seen in the delayed construction of the SGR in Uganda. Farmers in Mpigi district had to protest for their land rights after being left out of the compensation process. The low/lack of involvement of stakeholders in BRI projects has also caused public opposition and project delays in Uganda and Djibouti. Similarly, Park and Kim [

35] found that the social and environmental conflicts, delays in project implementation, and increased costs were all caused by the lack of stakeholder involvement and consultation in BRI projects.

High compensation prices: The delay in the construction of BRI projects such as the SGR in Kenya, Entebbe Express Highway and the SGR in Uganda as well as Ethiopia’s Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway was caused by disputes over compensation for landowners along the rail line and road. Some landowners claimed that they had not been adequately compensated for their land, and were demanding higher compensation. Similarly, the New Administrative Capital project in Egypt suffered from high compensation rates that led to an increase in land prices in the area. This finding is supported by the study by [

5] on the Laos-China Railway project which reported that the high compensation packages offered to affected communities have resulted in an increase in land prices, leading to additional economic pressures on the country. While compensation is necessary for communities affected by BRI projects, it is important to ensure that the compensation packages are reasonable and sustainable in the long term to avoid creating additional economic problems.

Procurement corruption: Procurement has posed some challenges in the implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Africa. Some of the notable challenges were lack of transparency, limited local participation, limited competition, and lack of capacity and expertise to effectively manage procurement processes for complex infrastructure projects. This finding is consistent with what [

53] reported. The author believes that that procurement of works such as bridges, railways, roads, and oil pipelines is particularly vulnerable to corruption due to their design and the difficulty associated with measuring costs especially by ordinary citizens. In Uganda and Kenya, the citizens have voiced their concerns about the government awarding contracts for BRI projects to Chinese firms. This is problematic because both the contractor and the project supervisor/consultant are often Chinese firms. This act is evidence of conflicts of interest which can have impacts on the project costs, quality of work, and transfer of skills and technology to the local workforce.

Labor violation: There have been a number of cases where labor violations have occurred in the projects under the BRI; for example Sinohydro Corporation, the contractor of the Karuma hydroelectric power plant project, has been criticized for labor violations, in terms of workers being physically abused by Chinese supervisors, poor working conditions, and low wages. Wang and Tang [

43] argue that labor violations are prevalent in BRI projects due to the weak labor protection laws and inadequate enforcement mechanisms in host countries, as well as the prioritization of project completion over worker safety and welfare by Chinese companies. Furthermore, refs. [

54,

55] noted that Chinese companies involved in BRI projects in Africa are often accused of labor violations, including poor working conditions, low wages, and lack of safety measures. They suggest that such practices can harm local communities and workers, and that it is important for Chinese companies to adhere to local labor laws and international standards in order to promote sustainable development in the region. They also note the need for greater transparency and accountability in BRI projects, including monitoring of labor conditions and worker safety.

Environmental hazards: The construction of infrastructure projects such as the construction of a ports, oil pipelines, railways, highways and airports could lead into significant environmental impacts such as deforestation, air and water pollution, soil erosion, and loss of biodiversity. A strand of the literature (for instance, [

52,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60]) has shown that these projects have significant environmental implications. It is therefore vital to carefully assess and mitigate these potential impacts to ensure that infrastructure development is sustainable and does not harm the environment.

Increasing debt levels: With countries like Kenya, Mozambique, Egypt, Uganda, and Djibouti lacking resources, especially financial resources, to spur their own developments, they have turned to China for financing through the BRI. This move has several benefits [

61]. However, the author cautions that while the BRI has the potential to bring significant benefits, it also poses significant debt risks that must be addressed. According to Gallanger [

62] the BRI has significantly increased debt levels of the recipient countries. This highlights the need more effective debt sustainability frameworks to address this issue/challenge. The result confirms Kupfer [

63] argument for integrating a component of debt relief into China’s BRI in order to address the growing debt challenges faced by recipient countries.

Lack of a formal BRI Secretariat: The absence of a BRI Secretariat can indeed make it more difficult to assess the risks and sustainability of BRI-related debt, which has raised concerns among some countries and international organizations. Additionally, it could also lead to corruption and mismanagement in BRI projects. It also makes coordination and monitoring project implementation across multiple agencies and countries difficult, which can further exacerbate the situation.

COVID-19 Pandemic: BRI projects have faced major hurdles due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Travel restrictions, lockdowns, and supply chain disruptions have caused setbacks in project implementation; for example, the New Administrative Capital City and the development of the Suez Canal Economic Zone (SCZone) are projected to take at least two more years due to delays (like the movement of personnel and resources from China as a result of travel bans) caused by COVID-19 [

36]. These have a significant effect on project timeline and costs. Similarly, the pandemic’s economic impact has resulted in reduced trade and investment flows, affecting the financial resources available for BRI projects.

Based on the findings and literature [

54,

56,

57,

58,

61,

62,

64], it is evident that the implementation of BRI projects in Africa has been marred by various challenges, including environmental injustice, labor violations, procurement corruption, low/lack of stakeholder involvement, COVID-19 pandemic, lack of a formal Secretariat and increasing debt levels. These challenges have resulted in social, economic, and environmental impacts that have affected the development of the beneficiary countries.

4. Policy Implications

The following are the major BRI significant policy implications to developing countries especially in Africa:

The lack of transparent procurement processes in some African countries can lead to inflated project costs, poor-quality infrastructure, and delays in project implementation. To mitigate these risks, it is important for each BRI-implementing country to develop robust procurement frameworks that prioritize transparency, competition, and accountability in the selection of BRI contractors and suppliers.

BRI projects have also led to displacement of communities, loss of livelihoods, as well as loss of biodiversity. This can result in high costs of compensation and resettlement. To address this, each respective Government should develop social safeguards and compensation frameworks that ensure affected communities are adequately compensated and resettled in a dignified and sustainable manner as well as trying to avoid routing the railways and roads through national parks and forests.

BRI projects have been associated with labor violations such as forced labor, physical abuse, and low wages in countries like Uganda and Kenya which have led to exploitation of workers and human rights abuses. There is a need to enforce labor laws and regulations that protect workers’ rights, ensure fair wages, and prohibit forced labor by the Chinese companies.

Furthermore, it is important to consider both short- and long-term environmental impacts of BRI projects, such as deforestation, pollution, and loss of biodiversity. To address these concerns, there is a need for the developing countries’ governments, especially in Africa, to uphold environmental regulations that protect natural resources, ecosystems, and wildlife. Complying with national and international environmental standards and guidelines is also key for mitigating negative effects caused by BRI projects.

The low/lack of involvement of local stakeholders in BRI projects can result in social and environmental conflicts, delays in project implementation, poor project planning and design, corruption, and ultimately a lack of sustainability and effectiveness of the projects. It is therefore important for BRI projects to ensure the active involvement and participation of local stakeholders to address these implications.

Lack of a BRI Secretariat in Africa limits the regions’ ability to effectively participate in decision-making processes unless they travel to Beijing, China. The lack of coordination could lead to inconsistencies in project implementation, delays, and even conflicts. The establishment of a BRI Secretariat in Africa would significantly improve communication between the parties and other development agencies that are not in position to travel to Beijing.

The challenges presented by COVID-19 to BRI projects resulted into a shift in priorities towards public health and economic recovery which affected the progress of the projects. To mitigate this, policymakers should integrate resilience measures, ensure responsible borrowing practices, promote multilateral cooperation, prioritize social and environmental impact assessments, and be flexible and responsive to evolving needs. By incorporating these, BRI projects can navigate the challenges posed by the pandemic and contribute to sustainable development in a post-COVID-19 world.

Finally, with some African countries like Djibouti which have taken on high levels of debt to finance BRI projects, concerns have been raised about the country’s ability to repay the loans. The high level of debt from BRI projects will therefore lead to reduced government spending on social programs like education and health which is a driver of every country and may also increase dependence on China for debt refinancing which in turn may compromise African countries’ sovereignty. Developing countries in Africa therefore must carefully evaluate the costs and benefits of BRI projects, ensuring transparency, sustainability, and alignment with their national development goals/plan, for instance Uganda Vision 2040, Kenya Vision 2030 and Egypt 2030 Vision as well as international development agendas like the AU Agenda 2063 and UN-SDGs 2030.

5. Conclusions

The BRI is China’s foreign and economic policy that aims to bridge the global infrastructure gap through the construction of modern highways, airports, high-speed railways, bridges, power generation (hydropower), and the development of industrial parks among the countries. The current African leaders have undeterred support for the BRI despite the mixed reactions it has generated. The infrastructure development of BRI projects in Africa has been significant, but implementation challenges remain, including labor violations, procurement challenges, environmental hazards, lack of stakeholder involvement, and high compensation prices. Additionally, BRI projects have been criticized for increasing debt burdens on African countries. Despite these challenges, BRI projects have the potential to significantly improve infrastructure in Africa and promote economic growth. Furthermore, researchers noted the likely competition from other development initiatives such as the proposed European Union (EU) “Global Gateway” and the US “Build Back Better World” (B3W) initiative which are likely to have both positive and negative implications for the BRI in Africa. This competition will increase scrutiny and pressure on China providing host countries with more options and opportunities for collaboration. The success of the BRI’s second phase will depend on how well it can navigate this competition and adapt to changing circumstances.

6. Limitations and Areas for Future Research

This study acknowledges its limitations in terms of scope of analysis, access to comprehensive data for comparing and assessing the impact of projects across different countries, and limitations in the sources used for analysis. The study relied mainly on analyzing existing documents rather than conducting interviews and focus groups. Future researchers can use interviews, focus groups and surveys to extend the scope of the study and compare results. From the literature, there is enough evidence that most studies on BRI projects in Africa have been conducted by foreign researchers or development agencies. Hence, there is a need for more research that: (i) incorporates local perspectives, including the views of African policymakers, business leaders and citizens; (ii) focuses on the gender and social impacts of BRI projects in Africa, including how they affect women, marginalized groups and vulnerable populations; (iii) studies governance and accountability issues, especially how these projects are being implemented, monitored, and evaluated, and whether they are accountable to local communities and national governments; (iv) examines the environmental issues and impacts of BRI projects; (v) investigates the security dynamics, particularly related to the Quad or the Indo-Pacific security architecture; (vi) examines how the BRI influences social and political development in the region; and (vii) investigates the trade opportunities between Africa and other regions like the Middle East, America, Europe, Asia, and Australia among others. In summary, to fully comprehend the impact of the BRI, we must focus on these key areas and approach its implementation and evaluation in a comprehensive and inclusive manner. By doing so, we can gain a comprehensive understanding of the situation, consider all stakeholders, and work towards creating a just and sustainable future for everyone involved.