Will the Cows and Chickens Come Home? Perspectives of Australian and Brazilian Beef and Poultry Farmers towards Diversification

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

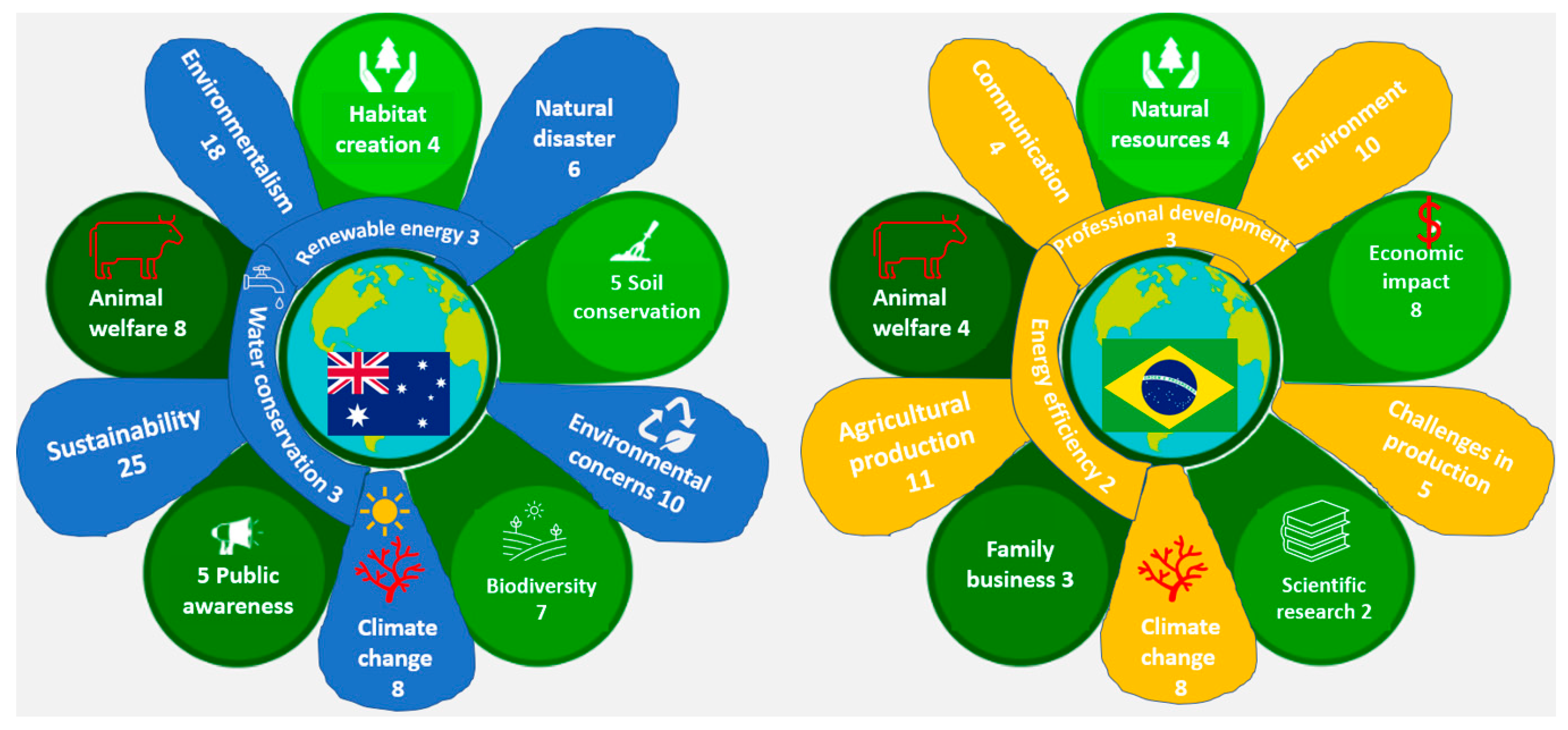

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Australia

3.1.1. Agriculture Industry

“I’m doing some duck eggs… [to] have some income coming in. And I was leasing a processing plant that was close to me, but unfortunately people that own that have moved on and they’ve sold it; so, I’m back to square one again.” (Poultry and beef farmer, NSW)

“Well, we looked at the eggs business and also…. looked at doing ducks in a fairly big scale for not much investment, but it would be something we need to contemplate doing because there’s no duck processing in the north of Sydney.” (Poultry farmer, NSW)

“We could make ducks without spending a fortune on our farm, but we will need money for processing plants and hatchery and some start-up money…, but you… could be left with nothing if there are no markets, and again devaluation in your assets… is what could happen, but at least you could start with little using what you’ve got…” (Poultry and beef farmer, NSW)

“We looked at many things. Fish farming… is very costly, (fish have) a short fresh life and are very hard to sell. Also, we had a few plans for mushroom farming and the other idea was for farm tourism. We could reload our broilers sheds and turn them into caravan storage and self-storage. But… it happened that you can’t do this on your own property, because it is… a rural area and if you want to do this you’ve got to get it rezoned…” (Poultry farmer, NSW)

“We are open to any options whatsoever, we need guidance. We’ve looked at… medical marijuana…, flowers…, mushrooms…, maybe we can look at other plant-based options…, but it seems for everything to start you need capital… There’s one guy… he did a trial [of mushrooms] and he said it looks viable. But he didn’t have the money to get the equipment to be able to produce these mushrooms, because it’s just so expensive.” (Poultry farmer, NSW)

“We want to do a hatchery… we haven’t got the infrastructure yet but… we have between us… $50 million worth of chicken-growing infrastructure in this region. The monopolist that discontinues our contracts is doing absolutely nothing and we can’t utilise what we currently have because of lack of available investments… You take chickens and grow them up to 16 weeks and they as hens start to lay eggs, this is a business for a lifetime. You haven’t got to spend a lot of money on changing your existing sheds to use them for egg production. You just need two or three million to get into it. But it is questionable… whether you can compete against the big boys, as small farms like us are not the same as Sunny Queen eggs or Steggles who’ve got most of the markets.“ (Poultry and beef farmer, NSW)

“… well, together [with] my parents we are in the cattle business… They pay our loan back to the partnership on adjusting the land, the cattle are… what’s kept us going…” (Poultry and beef farmer, NSW)

“We have lots of supporters which is great… Extensive livestock production industries were and still are vital to the national economy of Australia… It is a leading source of agricultural income… It will be stable. People will not be going to stop eating meat. Also, the industry is constantly trying to meet the increasingly high welfare standards which are without any specific ground and are also quite challenging sometimes.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“I was primarily a poultry farmer when we bought the farm, but we added some cattle to… have a stable income because it didn’t involve a lot of money, but you need sustainable livestock to… keep you going and… we also have additional benefits from the cows—they keep the grass mowed.” (Poultry and beef farmer, NSW)

“There are some real opportunities for me for agricultural and horticultural development I can build upon and most importantly I am away from cattle farming which lately was quite intense and even a bit heartbreaking, especially during droughts and unintended slaughter times. My grandchildren were very upset of the whole situation and actually this was my breaking point to give up… my cattle farming and look for a change… It was scary at the beginning, but the grandchildren are who made my move… easy.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“Every new business requires some kind of financing. Planting a few citrus trees is one thing, but to turn this into a business, there must be at least hundred trees… I think that even if I decide to start growing citruses, and especially mandarins… I will never give up my cattle farming as they could secure the financing of my business.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“Moving to Riverina…, I did my homework well. Despite the risk,… I wanted to cement my relationship with my grandchildren and to be their favourite grandpa again… I am not thinking of this as a transition as I am still probing but my chances are pretty good if played well. The region is Australia’s largest citrus-growing region.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“Availability of water to support irrigated agricultural produce is a major economic driver for me to start my farm in the Western Riverina… We were struggling in Goulburn with the regular water supply. Because of irrigation, it is possible for rice processing, wineries, citrus processing, sugar plums, tomatoes and more recently I started developing an almond-packing shed. I am trying a bit of everything… Rice and horticulture producers make up I heard around 90% of the farm businesses here. You can see it as diversifying…” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“Investment corporation, … to try and get a little bit of capital… I don’t meet the criteria, being a starter and a small farmer. They are monopolists. I’ve tried and… I’ve been to the… rural financial counselling service for New South Wales. … We do cash flows and things like that, but they just seem to be not supportive… We keep hitting brick walls with local government and then councils don’t really want to know you because you’re not big enough to compete with… monopolists.“ (Poultry and beef farmer, NSW)

“Regenerative farming, I think, will help me improve my long-term livelihood as a small-scale farmer and conserve resources. I added it to my chicken growing and this helped me… It will reduce costs, and improve crop yield due to the rotation and also the crop quality, which I think will give me better resilience… if my chickens are infected with bird flu or anything. With COVID-19 these things are a worry. This will help me survive market volatility and also any extreme climate events—droughts, or flood… It… could open some new green income streams for me… It is difficult to survive as a farmer these days if you don’t think of something else you can do to help yourself.” (Poultry farmer, NSW)

3.1.2. Environmental Conservation

“Mainly climate. We know livestock production is already affected and will be affected by changes in temperature… Flood, drought, you name it, we are experiencing it on our backs… in the Southern Tablelands and Southern Highlands region. Sometimes the post-drought effects are catastrophic… Other things like staff shortages, especially in the COVID times, was a big issue…, transport logistics problems [too]… We all need to improve our farmer bushfire preparedness to be ready to deal with fire events. Lately they seemed a lot… This causes complex issues, mainly welfare issues with the animals. These are unforeseen disease… problems with trade and even environmental catastrophes.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“As farmers we’re worried about many things, from cattle tags, shortage of feed resources, clean water, extreme heat and drought, fertiliser, vaccines, to low productivity and potential outbreaks like foot and mouth disease, IBK [infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis], ringworm, Q fever, chlamydiosis, leptospirosis, campylobacterosis, salmonellosis, listeriosis. You have to be ready to deal with any of these. It’s… hard sometimes, especially if you are forced to run a family business you inherited…” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“Lots of weather changes… unpredictable weather patterns, drought, flood, fighting with the environment… soil erosion, whatever comes… plus lack of money, declining production prices… big companies’ competition… These are not… factors you can control yourself. There are many uncertainties.” (Poultry farmer, NSW)

“If we leave aside the weather problems that farmers have to deal with, I think the prospects for the development of the sector are great. Beef is one of the most preferred [meats] by consumers in Australia… I find it very hard to imagine them replacing it with anything else.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“We have a small share, I think it was around 15–16% of the global beef production. But one of the best meats. We have a reputation for being clean and disease-free industry. I think the role of the livestock will be still huge.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“You have to have a good knowledge of your soil, water and plants’ function to produce healthier animals and healthier food. Everybody is looking for meat these days… for good, juicy, healthy meat. I am happy with my production. We sold quite a few tonnes for China and for the Middle East.” (Beef farmer, Western Australia)

“The beef cattle industry right now… is booming. Absolutely booming—two and three times more than what we were getting about three to four years ago. People like eating meat and also Australia is exporting meat.” (Beef farmer, Queensland)

“Environmentally, cows and farmers are working together… The climate,… the drought, the flood, does seem to be changed over the years as we don’t appear to get proper seasons anymore. I disagree that cattle are significant greenhouse gas producers as many are stating… They are better than us…. They are our babies.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“Apart from the greenhouse gases contributing to some climate change issues, cattle are fine… I am just sharing my opinion based on years of experience.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“I was thinking of growing cannabis. It seems profitable. I was thinking to secure a planting permit to satisfy all regulations. You need fertile land, irrigation, and a good climate to grow it. But also, you have to do your due diligence in protecting agricultural land.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“I just put [a] few years back some solar panels on the barn roofs. This is one way I found efficient to reduce the heating cost of my poultry units by generating heat using renewable energy…” (Poultry framer, NSW)

“I am not growing my chickens on a factory farm. They are ‘eco-chickens’… I have to be looking at… my chicken potentially to be carriers of disease, salmonella, food safety pathogens, different pests… many issues you have to be careful about. On top of this I am fighting with the elements, the production cost and also selling prices. Everybody wants to eat cheap food, but no one knows how difficult it is to raise a chicken… I always want to be upfront when I am thinking about transition… You really need to think about the hardship when you start to grow something completely different and…. the financial risk you take on in converting your existing business into something else. I preferred to leverage it by adding something in like my idea with the veggies growing to help me with what I already have.” (Poultry farmer, NSW)

“My business is going well. Of course, there are many issues with grazing and pasture, I heard some of the farmers have not so smart practices, some… have inadequate veterinary care, causing their livestock to become sick or even die from infection and injury. I am regularly doing everything I need to avoid all of these bad practices.” (Beef farmer, Western Australia)

“I’m very aware of the green movement… I was one of the first people to go to land-care meetings so we can (claim)… Landcare as an organization. That influenced me very much.” (Former beef farmer, NSW)

3.1.3. Business Challenges

“I have a four-shared farm with my parents. They are mixed farms with cattle, … beef cattle and poultry. Two years ago, we lost our contract for the poultry broiler production to Inghams… There’s been no opportunity to go to another processor… It’s all about the big guys, all about monopolistic development.” (Poultry and beef farmer, NSW)

“We found it extremely difficult because we’ve just lost our income that had 12 months-notice and then it’s been very hard to find another business to replace the poultry farming. A transition to something different. … and what we can do with tunnel-ventilated shared shed spaces that have been specialised for broiler chickens and we’ve spent a lot of money to get it to that high-standard… We’ve looked at additional high and low investment. We’ve been to a lot of consultancies—from agriculture firms to inviting big companies and advisers to come down and look at our sheds…” (Poultry farmer, NSW)

“In our situation with no income it’s very hard to get any support. We’ve been to government bodies, we’ve been everywhere and we’re still sitting here… with our poultry sheds empty—poultry sheds that have been devalued by 80%. And [there is] no real solution on how to get them back up and viable… I run a small farm but due to the restraints on capital I can’t make it viable overnight, because I just cannot borrow more money” (Poultry and beef farmer, NSW)

“I thought there would be some subsidies from the regional government for oranges’ growers, but there was not much there. As the majority of the oranges are grown up in farming families rather than corporate farms, growers are guaranteed service under the provisions of the Riverina Citrus. I am still trying to figure out how growers like me can remain financially viable.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“Our climate zone is not the best one. We have hot dry summer, cool winter. Farmers like me are relying merely on the rain they get, and the amount of water in their dams or streams. Soil is also not the best… mostly variable, including deep yellow sands, gravels, clay loams and heavier clay soils. What can I say? Lots of issues that need to be addressed. Plus, drought in the summer. Rain cannot get into the soil because it is so compacted, the vegetation has been removed from the cattle grazing and even there are some rainy moments the water runs away quickly before it can get into the soil.” (Beef farmer, Western Australia)

“My son gave me some money after he sold his car. He wanted us to invest in something different. He is not such an avid cattle farming lover,… he is quite a horticulturalist… Whatever he plants is going pretty well.” (Beef farmer, Western Australia)

“Working with bio stimulants was an interesting opportunity that was presented to me by my neighbour… The bio stimulant… helped the crop to develop greater resilience and increased biomass, but I thought it requires too much effort as you needed to apply it twice a year… for lessening the fertiliser applications, but I thought… it is too much effort for a cattle farmer like me. Regenerative agriculture was something I came up with… I like it a lot and it helps me improve the quality of the soil. It actually happened: bugs, fungi, bacteria, and all the other little creatures are now in my soil. It’s rich and concentrated. I can’t say I am an expert, but I’m still learning and understanding things. Regenerative agriculture is a continual journey of passion and observation. It really helps preventing the loss of topsoil and builds up the organic matter.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

3.1.4. Human Behaviour

“Yes, it started as something funny, when the grandchildren named all the cows which I never did before. At the beginning I thought it will be cool, but then when you kill Johnny, one of the cows that had my name, you start thinking twice before you kill Betty, a cow named after my wife. It’s becoming a personal affair…. It wasn’t pleasant at all…, it wasn’t fun anymore. I couldn’t sleep, couldn’t live like that, feeling the guilt that was inculcated by my grandchildren in me. I just needed a change. I needed to get rid of my cattle business. I needed to find something new to do.” (Beed farmer, NSW)

“I wasn’t scared to start something new, just because I had to do it for my grandkids… It was a bit risky as I didn’t know what to expect, but I had nothing to lose… I would rather keep the connection with the grandchildren than fight with them. I made a mistake with my younger son forcing him to be a cattle farmer like me and he ran away to be a lawyer. With his kids we kind of bond together and whatever they see (in) the future I want to see it with their eyes.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“The pushier cows would get some [food at the feedlot] and the skinnier ones were getting skinnier and skinnier and started dying on the property. So, … this huge sway of running bamboo that my mother, advisedly and unknowingly planted… came in handy during that drought… The cattle would be eating it because it was green…, but I’m… old. I’m 70 now… I fell over at one point, nearly stabbed myself through the stomach with sharp bamboo. And I thought… why bother?… I had no worries transitioning my land to being a conservation block. Yeah, because of my attitude to animals. I’m not a money hungry person… I think you’ve got to treat animals with respect.” (Former beef farmer, NSW)

“The sanctuary is on 100 acres. We transformed it from cleared sheep and cows’ paddocks to a haven for birds, and just in the last few couples of years for composers.” (Former beef farmer, NSW)

“What tipped the balance of everything was the drought of 2019… There was not a blade of grass anywhere… then I turned it into the sanctuary…” (Former beef farmer, NSW)

“Emotional factors” attracted the highest number of citations –19 (see Table 5), followed by “social factors”—11, and “motivational factors—10. The feelings that dominated were disappointment and disenchantment with the farmers’ existing agricultural practices that impact their personal lives but also the social environment where they live. It was interesting to observe that to cope with the negative emotions, some farmers had turned their properties into conservation land and had transitioned to running environmental sanctuaries.

3.1.5. Obstacles to Diversification

“Farm diversification, I think, is something that is becoming more common these days… to build some sort of economic resilience for farming families… When making a diversification, you should consider the impacts of this diversification on your own family. This is why many farmers are hesitant to pursue any changes to what they’re used to do. … they faced so many bravery-requiring things that other people will never imagine in their lives… but they want to do this period of adjustment from one thing to another slowly. This is the same with our case converting half of our land to a conservation area and the other still continuing to be the home of a small cattle herd and a few sheep… Diversification at the farm level excludes simple land-use change like in our case changing from growing cattle to regeneration and land conservation, but rather refers to something that is… the addition of an enterprise like growing cattle and trees to attract birds and other native species… You need to think of the off-farm income, and this should be examined carefully.”(Former beef farmer, NSW)

“I thought about changing into something different as I am getting older…, but I am hesitant as I don’t have the knowledge to start something new…. Starting something new is not at all easy, especially when you have been taking care of your cows all your life, and you know nothing else. And now you have to do something completely different.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“If I add on the cannabis business I may grow because of the demand, (I) could create some jobs as cannabis is quite hand-intensive… These are just thoughts at the moment; I haven’t done anything along this idea yet.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“Not sure what to expect. I heard from people like me that the cattle industry will shrink substantially… that we will be out of business. But I think it will not happen… They constantly threaten us with new technologies that would bury the industry, but all this is just empty talk. They also talk about meat grown in labs… We have so many meat-hungry mouths to feed and there’ll always be consumers thirsty for meat…” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“I am afraid whether the new thing I decide to start will give me the same level of satisfaction I am receiving working around my cattle herd. When you did what you do for ages you just can’t switch quickly.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“Now… lately I’ve heard they make some plant-based imitation meats. It is not meat at all and cannot be a… meat… It can’t in any way replace meat. We will always have cattle herds, look after them and produce good meat.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“I assume I will need lots of investment, I will need money from the government, council, or at least some financial support to start up. Also, the citrus trees will take some time to grow and there is no guarantee they will be fruiting. These are all risks… if I pursue with this business plan.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“I was using a drone I bought two years ago to monitor the figs growing from the house. It was a nightmare to deal with it… Later it did a good job, and I am still using it to monitor the trees. I was thinking of placing some cameras around… not resource-efficient and maintenance-efficient too, like the drone after all the troubles.” (Beef farmer, Western Australia)

3.1.6. Future Concerns

“Also land prices, feed, fertiliser, seed and pesticides continue being the biggest cost for us, the Australian beef farmers. I can see lately the farm cash incomes declined. It has never been huge for the livestock farms. But I am satisfied… I love my cows. They are still personally and financially rewarding for me… Our farm gives us everything we need to care about our family. The only thing is that I worry about the future.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“I think I would look into investing in functional foods, but unfortunately don’t have the funds to do so. That’s why I’d rather die as a cattle farmer. The problem is that everything in agriculture is terribly labour-intensive… If my children could be by my side, to support me, I would grow something else, fruit trees, citruses, mandarins, or something like that.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“I want to experiment with how I can influence the local climate, what we can change as a community with the existing system and go toward regenerative farming and then growing some crops, veggies perhaps. I think this is the only opportunity I have as a farmer to continue my business and look after my family without facing some financial bankruptcy in the future… But I worry… I just need to focus on creating more avenues for income to avoid any financial difficulties in the future. But no one can guarantee you this.” (Poultry farmer, NSW)

“It was quite difficult during COVID times… Everything is all about risks and hard work. We wish to start new things but often you experience things that at the beginning and halfway through make you to reconsider and to step back… It’s really difficult especially when you start something you’ve never done before.” (Former beef farmer, NSW)

“They are many new technologies that I believe will solve our agriculture. We had some people coming over offering us some drones to look after the cattle herds from a distance. I found it interesting but… why should I get involved in technologies I don’t know… They say there are software support teams if something wrong happens, but this support team will want money to support you. It’s always with money involved in and lots of uncertainties… If you don’t have them, you do less or nothing.” (Beef farmer, NSW)

“I think farmers are facing many things. They also can access the environmental conditions which are worsening because we destroyed nature at a rate that we shouldn’t. This is why the drivers which are potentially encouraging diversification are creating opportunity for family involvement in the current business, which is actually rare as the new generation is not voluntarily willing to be involved in the farming practices of their parents… So, creating opportunities for the children, siblings and partners, spouses should be around creating better prospects for lifestyle choices… They create something new, interesting, outside the farm and this is actually an ideal opportunity for spreading the potential financial risk. “ (Former beef farmer, NSW)

3.2. Brazil

3.2.1. Chicken Farmers

“We actually received a proposal to join a project from the agroindustry, where they would promote the construction of larger poultry houses. So, our transition from a smaller system, from a family company to… a family property to a more entrepreneurial property, emerged back in 2012.” (Poultry farmer, Parana)

“It was a time when it was profitable, not like today… people are already giving up here in the region at least, but at the time when I was working with the company, there was partnership… with a company here in the region…” (Former poultry farmer, now crops, Parana)

“Maybe a large-scale sustainable production, right? Let’s seek an alternative sustainable way to produce protein for everyone, which generates the minimum possible impact, the minimum waste, so that we can make the most of the environment, space and place. So that it’s not necessary to cut down all the trees, for example, in the Amazon, to grow soybeans.

… we have highly efficient production systems. Therefore, we can use less feed, less soy, less corn to produce the same kilogram of meat in systems that are often not conventional, are more technical systems. So, from my perspective as a farmer, we are… engaged in sustainable production because we can produce a lot of food, a lot of protein in a small space…”(Poultry farmer, Parana)

“Everything I’ve learned is that whether it’s animals or plants, a person needs to conduct a thorough study of what they will need so that… you don’t have to stop producing due to a lack of investment.” (Former poultry farmer, Parana)

“What discourages entry into such a system—of alternative proteins—is related to the market,… the lack of sales security… The opportunity of optimising the space we had there with a different production was raised, but there was no guarantee of purchase… I think we need public policies that provide both economic and extension incentives. We lack extension and knowledge…” (Poultry farmer, Parana)

“I believe that, in relation to farmers, there is still a lack of knowledge, extension services, and guidance on how to do things. Access to this knowledge is crucial because I ask myself: if I didn’t know, how would I proceed? As a result, people end up falling into the comfort of animal production. They think: ‘It’s fine as it is, I won’t make any changes.’ This aspect of public policy and extension services is still lacking in our country… The implementation of advanced farming techniques in poultry houses is only possible because we have people promoting and supporting it in the field every day. Without such support, there would be no progress. Therefore, I believe that public policy should come first. It’s not about giving someone a fish; it’s about teaching them how to fish.” (Poultry farmer, Parana)

“We don’t have the means to buy more land. We would like to have more land for cultivation, but the prices are very high, and it’s difficult to find available land for sale. It’s challenging to sell land, … because there is a lot of vegetation, and nowadays, deforestation is prohibited. We stick with what we have… That’s why I believe in taking good care of what we have because if not, we would have to rent additional land, which would be costly and reduce our profits. It’s important to do our best with what we have in order to maximize our harvest.” (Poultry and crops farmer, Parana)

3.2.2. Beef Farmers

“… thinking about the production chain as a whole, I end up betting that the greatest difficulty now is environmental instability. It’s the instability caused by global warming that brings more frost, more drought, and then suddenly a month of rain, which theoretically is good because it’s raining, but it’s not good to be flooded. … And then this snowball effect begins, and that’s what is causing the instability of profitability…” (Cattle and crops farmer, Parana)

“In relation to livestock and agriculture, agribusiness, there is a great difficulty in our communication when there is, let’s say, criticism towards the agribusiness sector, which, like any sector, has people who do well and people who do poorly. But we know that this discussion, unfortunately, is biased… Speaking of pasture, we know that the type of grass planted has a specific height, and the management of the pasture should be based on maintaining an optimal leaf area index to intercept 95% of light. It has been proven, back in 2002 during the International Meat Congress, that there have been a series of studies… showing that systems that respect the proper entry and exit heights and efficiently manage pastures have a much greater degree of mitigation of emissions…

When we talk about the environment, people often say, ‘Oh, the pastures are degraded…’ Indeed, in extensive extractive systems, pastures do get degraded. However, the path to follow is not degradation but rather maintenance. After all, it is much more expensive to restore a pasture than to maintain it…” (Cattle and crops farmer, Rio Grande do Sul)

“… Which of the chains consumes… more natural resources? Because, whether we like it or not, the production of, for example, peas, when it comes to plant production, needs to be extremely efficient due to the area it occupies… There is a lot of research to be done in this regard… it requires serious, focused projects that evolve gradually. And yes, the discussions are often framed as choosing between one or the other, but in reality, I believe there is a consolidated model that is a commercial model and is delivering meat, and for any new or alternative model to succeed, it needs a structured chain, production systems, and knowledge. …” (Cattle and crops farmer, Rio Grande do Sul)

“We do not engage in confinement operations within our family. However, we have worked with some clients, focusing more on the utilization of waste, which aligns with our approach… Until four years ago, before we began our collaboration, they incurred costs to either burn or produce a certain amount of energy from these by-products.” (Cattle and crops farmer, Rio Grande do Sul)

“And it was really interesting because, recently, my father has also embraced this approach… We could see that the animals weren’t comfortable. So now we have a completely different system, and many people question it… But they have said to me, “Oh my God, how you’ve changed!”… And my father is passionate about cow-calf operations. He says, “How can we treat the mothers and calves the way you used to?” It really upsets him. And I believe in the law of return, you know? After we started increasing our good practices, everything seemed to flow much better. We had much lower mortality rates, far fewer problems… It’s really difficult because we, who have studied all the principles of animal welfare, shouldn’t have to explain or justify it. It’s their right. Unfortunately, to convince someone… you always have to focus on the financial aspect.” (Cattle and crops farmer, Santa Catarina)

“… there used to be rough handling of the cattle, often poking and such, but now we use flags as a form of signalling. So there has been a complete shift in culture and handling practices, and it’s better for everyone. The cattle are much calmer and easier to work with. This is how we work now, with a great deal of care and respect for the animals…” (Cattle and crops farmer, Rio Grande do Sul)

“So, it will evolve, it will become cheaper, I have no doubts about that…, but there are still many years ahead, there’s still a long way to go. There’s a lot of chicken to be produced, a lot of pork to be produced, a lot of cattle to be produced… and fish as well, before this alternative has a more significant space in the market. I believe I won’t see that. Maybe my children will see it, but I don’t see it as a competing product from a market standpoint.” (Cattle farmer, Rio Grande do Sul)

“… there are two aspects to consider here: the younger generation has a greater concern for animal welfare and fewer prejudices. They are more open to adapting to new realities, technologies, and products. Therefore, there is still an opportunity for alternative proteins because these young individuals will want to protect animals and may not want to consume meat obtained through traditional means when there is an alternative available. These young people will become the adults of tomorrow, with increased financial capacity and influence as decision-makers or influencers in the purchasing process.” (Cattle farmer, Rio Grande do Sul)

“… I believe there is a market for everyone, but what concerns me is the issue of supply chain organisation… It is not easy to organise, and that’s where the challenge lies. I think it’s unlikely that plant-based meat will compete with beef. In my opinion, it’s more of a niche business, and those who are willing to embrace it will buy it, even though it comes at a higher cost. However, one aspect that still needs further discussion is the water consumption involved in the production of alternative proteins. We need to analyse the entire life cycle and determine which of the two options causes less contamination. Because we are aware of the ideology surrounding animal welfare, but it is important to determine how much of it is driven by desire or reality?!” (Cattle and crops farmer, Rio Grande do Sul)

“… we are eight billion people, and seven and a half billion people are still experiencing hunger. So how are we going to address the needs of all these people? That’s my concern. We have productive areas, not only in Brazil but also in other countries. We have regions that can produce simpler things to feed people, rather than focusing on cultured meat or alternative proteins. That’s my perspective, as someone with a lot of information and technical knowledge, although I don’t have a PhD. It comes down to basics like beans and rice. We need to consider practicality in addressing hunger, and the development of cellular meat and alternative proteins is indeed highly sophisticated. They may have more potential in the future.” (Cattle farmer, Rio Grande do Sul)

“… there will be a lot of work to be done to carve out a space in the market, especially in developing countries, or more accurately, in underdeveloped … countries. Of course, in Germany, the United States, Canada, Japan, it’s a different story.” (Cattle farmer, Rio Grande do Sul)

“I see that if we have other opportunities in the future and someone says, “Look, is there something we can do here that can generate income? Should we do it or not?” What I would like to have, is an already generated demand. I think that creating a market first, then creating demand, and then going after those customers is much more complicated than already having a generated demand and saying, “Hey, I have a product here for you… I will produce it with quality for you.” (Former cattle, now crops farmer, Parana)

“… the market has a need for alternative protein sources, but there isn’t yet a culture around it. It seems to be more of a lifestyle choice that doesn’t integrate into the everyday life of Brazilians. We already have important protein sources like beans, soybeans, and even rice as an alternative protein source. However, when we consider diversifying and investing, there is a risk of entering a market that doesn’t yet recognise these alternatives as protein sources. In the agricultural sector, I have a greater level of certainty and a more established business plan compared to the grain sector. We are more susceptible to risks in the latter case.” (Cattle and crops farmer, Sao Paulo)

“We can feel it at the hotel because, well… the frequency of guests requesting vegetarian options, gluten-free options, and so on, has increased. Quite significantly! We didn’t have anything before, and now we have enough to constantly be thinking about it… It’s not a lot yet, but it’s definitely noticeable.” (Cattle and crops farmer, Parana)

“So, could it become half cattle and half alternative crops? It’s possible! But not next year. And it really won’t be! There needs to be a whole process of persuasion… and there’s another thing as well, the generational issue. Who are the big farmers? Are they young people? No. They’re still the grandparents of the young ones, some of them are the parents of the young ones. So, everything new that we bring here takes about one to three years to convince, to show that somewhere else is convincing, you know?… So, expecting to make these changes in less than 10 years, people can’t do it because there’s resistance, because the landowners themselves have always done it this way. And their parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents have also always done it this way…“(Cattle and crops farmer, Parana)

“We started without my uncles… In 2000, they tried to plant soybeans, but it didn’t work out. … Today, different varieties have been introduced, more resistant ones, but they still have a trauma from that experience. So, we decided to lease the land to third parties… Now, it’s these third parties who plant… All the soybean fields are managed by them, and they pay us a rent for it and also provide us with winter pasture that they plant.” (Cattle and crops farmer, Rio Grande do Sul)

“Indeed, you can’t take too many risks. So, again, why did I say, ‘Oh, it won’t happen in the medium term’? In my opinion, it can certainly happen, but in the long term, because people will need time to test planting beets on 10 hectares, maybe even a combination of peas, chickpeas and beets. A diversified crop. Beautiful! To me, that’s the pinnacle of agricultural technology because you’re mimicking nature. You’re promoting diversity, and you won’t have pests in the same quantity as you would with monoculture… You won’t need as many pesticides, or perhaps none at all… People first need to be convinced that it will be profitable… There has to be demand. And demand needs time to mature and grow, right? Then, there will be a period for farmers to start considering it as a good idea because they need to see other brave farmers… making money from it… And then there’s the time for them to start on a small scale and gradually increase to a larger scale. Yeah… that will take a few years.” (Cattle and crops farmer, Parana)

“EMBRAPA [the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation] needs to publish numerous articles, conduct various studies, and universities should also conduct multiple studies… It has to be done! You need to establish partnerships with farmers. We have tried in various ways to involve the university in our farm, but they don’t come.” (Cattle and crops farmer, Parana)

“When there are brochures and publications being released about chickpea production or even lab-grown meat production, showing you invest this much and get this much in return. And you sell it to this market, and you need to be cautious about this particular bias, or maybe a certain pest, you know, these kinds of things that can happen, and it won’t deviate much from that because we have been studying this for 50 years… and we have extensive research spanning 10 years, right? So there’s a level of security and ease… But now, I don’t understand… how can we achieve scalability, right? The farmers will always be like, “Whom do I talk to in order to learn?” I want to do it. I’m someone who wants to do it. But whom do I talk to?“ (Cattle and crops farmer, Parana)

“I worked at BRF and also worked at Coca-Cola. And it was like this, they already came with the project set up, of course it’s a different company, but they have that… If you have a certain problem, I have a solution for it. They are in their comfort zone, while we, at a much smaller scale, are in ours, and that’s what makes us afraid to take risks. With cattle, or with soy and corn, when there is a problem, we know what to do. So, in a new diversification, a new crop, you start thinking: what if I encounter a problem? Who do I turn to for help?” (Cattle and crops farmer, Santa Catarina)

“… If you raise a calf, you can manage it much better because then you can put it in confinement, do other things that don’t solely depend on nature and the land’s response there, right?… We’re anxious to know, ‘Is it really worth it for me to switch if I sometimes don’t have as reliable partners in my region, for example, like I do for sugarcane?’ I don’t have a partner for alternative sources to lease, for example, or even someone to join forces in production, but there are many people… I’ve talked to my neighbours, we’re starting to learn. And then you say, ‘Hey, you can make better use of it. There’s idle land.’ And then everyone asks, ‘But how? How do we start?’ I even thought about talking to the sugar mill itself, which deals with soil rotation, and see if I can already expand to crops in those areas with less investment, through trial and error initially.” (Cattle and crops farmer, Sao Paulo)

“… to have effectiveness and reduce loss, which for me as a nutritionist is heartbreaking to see many farmers experience significant crop failure, and that loss cannot be recovered. Today, there are some alternative methods being implemented, but it’s one of the factors that often hinders the consideration of investing in diversification due to fear of the risks involved and the potential crop failure until it reaches the end consumer… We see the potential to implement agriculture, but we are afraid, ‘What should we plant?’ Because sometimes, we may end up shooting ourselves in the foot. We also have to consider whether we should invest right away in irrigation, which can be an investment that may require changing our focus later on. Therefore, these points of effectiveness in production are indeed sensitive areas that require careful attention.” (Cattle and crops farmer, Sao Paulo)

“In reality, I think there will always be risks in both, right?… In animal farming, there are risks related to diseases, reproductive cycles, droughts, and when they occur, we have to act quickly and provide the necessary support. These are essentially the same incidents that can also happen in crop farming, which heavily relies on climate conditions, such as droughts.” (Cattle and crops farmer, Parana)”

“This year it seems even more unpredictable due to global warming and the greenhouse effect. The winter has been irregular so far, even in October. There have been frosts in September when we should be planting, which is completely different from what we expect during the rainy season. We depend on the climate for both animal and crop farming activities…” (Cattle and crops, Parana)

“… In 2006 and 2007, we had consecutive years of severe frost. After I had prepared the coffee plantation for the next season, another frost came and destroyed everything again. When the second frost hit, the decision to quit coffee production was definitive… So, when I saw this situation and witnessed the emergence of new technologies for soybeans with good profitability…, I just weighed the options and decided to abandon coffee and start with cash crops.” (Cattle and crops farmer, Parana)

“… I see these moments as opportunities to seek different technologies, to establish partnerships, and to engage with people who have more knowledge than us. I believe that innovation also involves being open to research institutions, companies, and individuals who can contribute their expertise. … I think the solution is regionalised and specific to each case. It’s not useful to assume that there’s a universal solution that will solve everyone’s problems because it doesn’t work that way. What makes sense for our reality here may not make sense for the reality in Londrina or Roraima, and so on.” (Former cattle, now crops farmer, Parana)

“How does a company that demands carbon neutrality or something similar from its suppliers come into play? However, it is still in its early stages. I see that the opportunity is significant because we have a lot of land to use, and we know that sustainable practices can be leveraged. But until there is a market for it, we are somewhat limited because there may not be legal or economic support for such initiatives yet. However, it is indeed a possibility that we are considering!” (Former cattle, now crops, Parana)

“… agriculture is often compared to the evolution of medicine, especially because my father is a doctor. Areas where planting soybeans seemed unimaginable in the past are now possible due to the genetic development of seeds, varieties, and irrigation systems. The work of institutions like EMBRAPA and research institutes is crucial in this regard.” (Cattle and crops, Rio Grande do Sul)

“[subsidies] are valid. But I am not in favour of such strategies. I prefer that universities go to the producers and invite ‘let’s do a joint research project that will improve your business’. I believe this is more productive, more solid in the long run than subsidies, less costly to the government and to the country.” (Cattle, Parana)

“This question is very simple to solve, to answer… It’s human resources… Human resources are the biggest challenge we face. To assemble a team… to assemble a committed team, it’s really difficult… There are people who have the technical skills, I’m not talking about formal qualifications, but who have technical knowledge and who are willing to be committed to the project, willing to do things the way they are established to be done, and who are honest and committed.” (Cattle, Rio Grande do Sul)

“And I see that there is a significant gap between the actual problems faced by rural properties, which can be solved through technology, and what companies and urban areas imagine to be the problems of farmers. As a result, they sometimes end up solving problems that don’t actually exist.” (Former cattle, now crops, Parana)

4. Diversification for Australian and Brazilian Farmers

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guyomard, H.; Bouamra-Mechemache, Z.; Chatellier, V.; Delaby, L.; Détang-Dessendre, C.; Peyraud, J.-L.; Réquillart, V. Review: Why and how to regulate animal production and consumption: The case of the European Union. Animal 2021, 15 (Suppl. 1), 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, K.D. Emissions inventories and their implications for intensive animal production. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Greenhouse Gases and Animal Agriculture, Obihiro, Japan, 7–11 November 2001; pp. 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, G.; Kassas, B.; Palma, M.A.; Risius, A. Perceptions of antibiotic use in animal farming in Germany, Italy and the United States. Livestock. Sci. 2020, 241, 104251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tello, J.; Garcillan, P.P.; Ezcurra, E. How dietary transition changed land use in Mexico. Ambio 2020, 49, 1676–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro Machado Filho, L.C.; Seó, H.L.S.; Daros, R.R.; Enriquez-Hidalgo, D.; Wendling, A.V.; Pinheiro Machado, L.C. Voisin Rational Grazing as a sustainable alternative for animal production. Animals 2021, 11, 3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, C.; Reyes, J.; Elias, E.; Aney, S.; Rango, A. Cascading impacts of climate change on southwestern US cropland agriculture. Clim. Chang. 2018, 148, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- OECD/FAO. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2022–2031; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Sheng, L.; Zhang, D.; Li, L.; Wang, A. Study on the pollution status and control measures for the animal and poultry breeding industry in northeastern China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 4435–4445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yulia; Bahtera, N.I.; Herdiyanti; Hayati, L. An alternative policy of animal farmers’ empowerment towards environmental vision. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Green Energy and Environment (ICoGEE 2020), Bangka Belitung Islands, Indonesia, 8 October 2020; p. 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.; Thornton, P.K.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Palmer, J.; Benton, T.G.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Bogard, J.R.; Hall, A.; Lee, B.; Nyborg, K.; et al. Innovation can accelerate the transition towards a sustainable food system. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). Sustainable Development Group. Leave No One Behind. 2023. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/2030-agenda/universal-values/leave-no-one-behind (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Bryant, C.J.; van der Weele, C. The farmers’ dilemma: Meat, means, and morality. Appetite 2021, 167, 105605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villano, R.A.; Koomson, I.; Nengovhela, N.B.; Mudau, L.; Burrow, H.M.; Bhullar, N. Relationships between Farmer Psychological Profiles and Farm Business Performance amongst Smallholder Beef and Poultry Farmers in South Africa. Agriculture 2023, 13, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufino, M.C.; Hengsdijk, H.; Verhagen, A. Analysing integration and diversity in agro-ecosystems by using indicators of network analysis. Nutr. Cycles Agroecosyst. 2009, 84, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedde, L.; Katz, J.; Menard, A.; Revellat, J. Agriculture’s Connected Future: How Technology Can Yield New Growth. McKinsley & Company. 9 October 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/agriculture/our-insights/agricultures-connected-future-how-technology-can-yield-new-growth (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Piñeiro, V.; Arias, J.; Dürr, J.; Elverdin, P.; Ibáñez, A.M.; Kinengyere, A.; Opazo, C.M.; Owoo, N.; Page, J.R.; Prager, S.D. A scoping review on incentives for adoption of sustainable agricultural practices and their outcomes. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Censo Agro 2017. Brazil: All. Available online: https://censoagro2017.ibge.gov.br/templates/censo_agro/resultadosagro/pecuaria.html?localidade=0&tema=1 (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Fasiaben, M.C.R.; Almeida, M.M.T.B.; Maia, A.G.; de Oliveira, O.C.; Costa, F.P.; Barioni, L.G.; Dias, F.R.T.; Moreira, J.M.M.Á.P.; Sena, A.L.S.; Santos, J.C.; et al. Technological profile of beef cattle farms in Brazilian biomes. Poultry Farming in Brazil—Management Practices. Boletim de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento 48. Poultry Farming in Brazil—Management Practices|Agri Farming. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/347197756_Technological_profile_of_beef_cattle_farms_in_Brazilian_biomes (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Safe Food Queensland. Spotlight on Australia’s Poultry Meat Industry. Available online: https://www.safefood.qld.gov.au/newsroom/spotlight-on-australias-poultry-meat-industry/#:~:text=There%20are%20more%20than%20800,32%25%20of%20total%20national%20production (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Financial Performance of Livestock Farms, 2020–2021 to 2021–2022. Financial Performance of Livestock Farms—DAFF. Available online: agriculture.gov.au (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Chavez-Lindell, T.L.; Moncayo, A.L.; Vinueza Veloz, M.F.; Odoi, A. An exploratory assessment of human and animal health concerns of smallholder farmers in rural communities of Chimborazo, Ecuador. PeerJ 2022, 9, e12208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, N. Farms Are Adapting Well to Climate Change, but There’s Work Ahead. The Conversation. 29 July 2021. Available online: https://theconversation.com/farms-are-adapting-well-to-climate-change-but-theres-work-ahead-164860 (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Gaur, A. Comparing Nvivo and Atlas.ti: A Comprehensive Analysis of Qualitative Data Analysis Software for Researchers. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/comparing-nvivo-atlasti-comprehensive-analysis-data-gaur-ph-d-/ (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- CSIRO and Bureau of Meteorology. Climate Change in Australia, Information for Australia’s Natural Resource Management Regions: Technical Report, CSIRO and Bureau of Meteorology, Australia. 2015. Available online: https://www.climatechangeinaustralia.gov.au/media/en/publications-library/technical-report/ (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Hughes, N.; Gooday, P. Analysis of Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation on Australian Farms; ABARES Insights; Australian Government Department of Agriculture Water, and Environment Canberra: Canberra, Australia, 2021. [CrossRef]

- NSW Farmers. Paltry Returns for Poultry Meat Farmers. 28 June 2020. Available online: https://www.nswfarmers.org.au/NSWFA/Posts/News/mr.059.20.aspx (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Jose, H.; Condon, M. Biggest Chicken Processors to fix Unfair Contracts with Farmers after ACCC Investigation. ABC News. 26 May 2022. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/rural/2022-05-25/accc-orders-poultry-processors-to-improve-unfair-contracts/101097390 (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Burt, M. Poultry Returns: A Family Livelihood Decimated. The Farmer. 29 June 2020. Available online: https://thefarmermagazine.com.au/two-families-in-the-poultry-industry-have-lost-everything/ (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Massy, C. The Call of the Reed Warbler: A New Agriculture a New Earth; University of Queensland Press: Brisbane, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wait, A.; Meagher, K. Climate Change Means Australia May Have to Abandon Much of Its Farming. College of Business and Economics, ANU. 6 September 2021. Available online: https://cbe.anu.edu.au/news/2021/climate-change-means-australia-may-have-abandon-much-its-farming (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation (QAAFI). Australian Agriculture and Climate Change: A Two-Way Street. Australian Academy of Science. 23 September 2021. Available online: https://qaafi.uq.edu.au/blog/2021/09/australian-agriculture-and-climate-change-two-way-street (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Howden, S.; Crimp, S.; Nelson, R. Australian agriculture in a climate of change. In Managing Climate Change: Papers from the Greenhouse 2009 Conference, Perth, WA, Australia, 23–26 March 2009; Jubb, I., Holper, P., Cai, W., Eds.; CSIRO Publishing: Collingwood, VIC, Australia, 2010; pp. 101–111. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284969880_Australian_agriculture_in_a_climate_of_change (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Better Health. Rural Issue—Losing the Farm. Victoria State Government. Available online: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/servicesandsupport/rural-issues-losing-the-farm (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Smith, A. Depression, Anxiety, Rife among Aussie Farmers with Nearly Half Considering Self-Harm or Suicide. Countrymen. 29 March 2023. Available online: https://www.countryman.com.au/countryman/country-communities/depression-and-anxiety-rife-among-aussie-farmers-with-nearly-half-considering-self-harm-or-suicide--c-10140055?utm_campaign=share-icons&utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=social&tid=1680063103376 (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Newton, P.; Blaustein-Rejto, D. Social and economic opportunities and challenges of plant-based and cultured meat for rural farmers in the US. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 624270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais-da-Silva, R.L.; Reis, G.G.; Sanctorum, H.; Molento, C.F.M. The social impacts of a transition from conventional to cultivated and plant-based meats: Evidence from Brazil. Food Policy 2022, 111, 102337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, J.d.P.S.; Fiedler, R.A.; Sucha Heidemann, M.; Molento, C.F.M. First glimpse on attitudes of highly educated consumers towards cell-based meat and related issues in Brazil. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morais-Da-Silva, R.L.; Reis, G.G.; Sanctorum, H.; Molento, C.F.M. The social impact of cultivated and plant-based meats as radical innovations in the food production chain: The view of specialists from Brazil, the United States and Europe. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 1056615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Farm Institute. Farm Subsidies Alive and Well, and About to Grow Again. 2 February 2016. Available online: https://www.farminstitute.org.au/farm-subsidies-alive-and-well-and-about-to-grow-again/#:~:text=Australia%2C%20by%20contrast%2C%20has%20virtually,for%20the%20overall%20agriculture%20sector (accessed on 1 August 2023).

| Opening questions | Tell us about yourselves. What types of farms do (did) you have, and how long have you been in business? |

| General questions | What are the key issues nowadays farmers are facing? What do you think are the perspectives for the industry—short-term and long-term? What are the opportunities for your business? |

| For farmers who had made the change and had transitioned to other types of production | What motivated you to make the change? How long have you been considering the transition? Did you make any changes to your animal business to improve it before the transition, and when and why? Did anyone or any organisation have a particular influence on your decision to make the transition? Did anyone or any organisation have a particular influence on your planning for the transition? What encouraged you to change your cattle/poultry farming business? Was it easy? How diversified is your business? Did you receive any support, and from whom? |

| For farmers who had not decided to make a change but were thinking about it | What will motivate you to make the change? Describe the care you take of your animals. What will influence you toward making a change in your current business? What will encourage you to make a transition? What will it take? (e.g., climate change, economic, methane production etc.) What will discourage you from making the change? (e.g., risk, economic concerns etc.) Are there any subsidies or other incentives for switching to other activities for transforming your business into a plant-growing business, and will you be willing to switch and why? Would you be willing to make a change to reduce any risk? What would that be? Have you thought about diversification toward production with a lower environmental footprint from what you are currently producing? Are you aware of any agri-food technological and innovation solutions that could be beneficial for your business? |

| Concluding question | Would you like to add something else that is of importance to be mentioned and wasn’t discussed? |

| Farmer # | Type of Production | Location | Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | |||

| 1 | Poultry and beef | New South Wales | 279 ha, 10 sheds |

| 2 | Poultry | New South Wales | 129.5 ha, 6 sheds (100,000 chickens) |

| 3 | Poultry and beef | New South Wales | 20 ha |

| 4 | Poultry | New South Wales | 26 ha, 13 sheds |

| 5 | Beef | New South Wales | 182 ha |

| 6 | Beef | New South Wales | 67.5 ha |

| 7 | Beef and sheep, conservation | Queensland | 58 ha |

| 8 | Beef | New South Wales | 486 ha |

| 9 | Beef | Western Australia | 235 ha |

| 10 | Former cattle, sheep and poultry transformed into conservation area as wildlife sanctuary | New South Wales | 129.5 ha |

| 11 and 12 | Former sheep and cattle farm transformed into conservation as wildlife sanctuary | New South Wales | 40 ha |

| 13 and 14 | Former sheep and cattle farm transformed into conservation as wildlife sanctuary | New South Wales | 57 ha |

| Brazil | |||

| 15 | Poultry | Parana | 4 sheds |

| 16 | Former poultry | Parana | n/a |

| 17 | Former poultry | Parana | n/a |

| 18 | Poultry and crops | Parana | 0.18 ha (shed size) |

| 19 | Former poultry, now crops | Parana | 0.12 ha (shed size) |

| 20 | Cattle and crops | Parana | 1000 ha |

| 21 | Cattle and crops | Rio Grande do Sul | 8600 ha |

| 22 | Cattle | Rio Grande do Sul | 1970 ha |

| 23 | Cattle and crops | Parana | 358 ha |

| 24 | Cattle and crops | Parana | 358 ha |

| 25 | Former cattle, now crops | Parana | 8500 ha, 2500 ha used for crops |

| 26 | Cattle and crops | Sao Paulo | 324 ha |

| 27 | Cattle and crops | Santa Catarina | 400 ha |

| Term | # | Term | # | Term | # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | 54 | Investment | 4 | Duck breeding | 2 |

| Entrepreneurship | 15 | Monopoly | 4 | Regenerative agriculture | 2 |

| Small-scale farming | 14 | Income diversification | 3 | Challenges | 2 |

| Land management practices | 9 | Sustainable agriculture technique | 3 | Industry changes merger | 1 |

| Economics | 8 | Tree conservation | 3 | Medicinal marijuana | 1 |

| Business management planning and strategy | 7 | Fruit tree growing | 2 | Hydroponics | 1 |

| Business opportunity, growth and development | 7 | Farm diversification | 2 | Horticulture | 1 |

| Livestock breeding | 4 | Aquaculture | 2 | Mushroom growing | 1 |

| Term | # | Term | # |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship | 19 | Economic opportunity | 6 |

| Business/small business | 17 | Business expansion and growth | 5 |

| Diversification | 10 | Market competition/trade | 5 |

| Risk-taking and management | 10 | Income diversification | 4 |

| Financial constrains | 10 | Government bureaucracy, policy and regulations | 4 |

| Investment | 9 | Monopoly | 4 |

| Business strategy/development | 9 | Barriers to entry | 4 |

| Business planning and realisation | 9 | Market demand | 4 |

| Innovation | 7 | Tourism industry | 3 |

| Logistics | 6 |

| Term | # | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional influences | 19 | Frustration, regret, confusion, disappointment, guilt Passion, resilience, responsibility, hopefulness Pride, knowledge Scepticism, stress, betrayal Struggle, survival, trauma Attitudes, expectations |

| Social influences | 11 | Challenges, difficulties, limitations, obstacles Insecurity, risk, neighbourly disputes Interest, expectations Regulations, preference |

| Motivational influences | 10 | Skills, occupation, adjustment, acknowledgement Success, achievement, attention to detail, fairness Self-doubt, self-efficacy |

| Term | # | Term | # |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainties | 13 | Lack of knowledge | 7 |

| Finances | 10 | Regulatory/licensing | 4 |

| Technologies | 8 | Collaborations | 4 |

| Government support | 8 | Contract terminations | 3 |

| Term | # | Term | # | Term | # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainties | 12 | Risk-taking | 6 | Retirement planning/aging concerns | 4 |

| Career change, opportunities | 7 | Lack of clarity, control, guidance | 6 | Missed opportunity | 4 |

| New skillset and expertise shortage/staff shortage | 7 | Anti-alternatives/technology skepticism | 5 | Decision-making | 4 |

| Self-reliance and improvement | 6 | Fear of the unknown/resistance to change | 5 |

| Term | # | Term | # | Term | # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economy | 6 | Interests and preferences | 2 | Technology | 2 |

| Family responsibility | 6 | Uncertainty | 2 | Stress | 2 |

| Work and animal welfare | 6 | Agricultural and livestock production | 2 | Family farming | 2 |

| Business | 4 | Investment | 2 | Finances | 2 |

| Financial difficulties | 3 | Innovation | 2 | Work | 2 |

| Animal production | 3 | Rural development | 2 | ||

| Change | 3 | Agriculture | 2 |

| Term | # | Term | # | Term | # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | 13 | Work and animal welfare | 4 | Decision making | 3 |

| Family farming | 10 | Rural development | 4 | Entrepreneurship | 3 |

| Work and animal welfare | 6 | Challenges and prospects in the sector | 4 | Planning | 2 |

| Economy | 8 | Agricultural and livestock production | 4 | Fish farming | 2 |

| Change | 5 | Interests and preferences | 3 | Research ethics | 2 |

| Work environment | 5 | Public policies | 3 | Financial limitation | 2 |

| Production | 4 | Investment | 3 |

| Term | # | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | 13 | Agricultural production, agriculture, agribusiness |

| Environment | 10 | Environment, environment/animal protection, environmental impact, environmental preservation |

| Financial aspects | 7 | Financial resources, financial concerns, economic instability, economic problems, economics, energy efficiency |

| Climate change | 5 | Climate, climate change, instability |

| Communication difficulties | 4 | Communication difficulties, communication in agriculture, opinion analysis |

| Personal development | 3 | Personal development |

| Family business | 2 | Family business |

| Term | # | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Vegetarian diet | 12 | Vegetarian diet |

| Market and business development | 11 | Market view, economy, market risks, market need, business development, business growth |

| Critical vision | 6 | Critical view of academia and scientific research, critical vision, criticism of vegetarianism, doubt, need for more studies and data, personal opinion (negative) |

| Socioeconomic challenges | 3 | Socioeconomic challenges |

| Sustainability | 3 | Sustainability |

| Financial investments | 2 | Financial investments |

| Social inequality | 2 | Social inequality |

| Term | # | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | 54 | Knowledge and professional growth, interest in learning and research, research, knowledge sharing, interest in learning, need for knowledge, university role, need for technical guidance, learning, educational limitations, need for technical knowledge, technical knowledge, knowledge appreciation, knowledge transfer, lack of knowledge |

| Financial aspects | 33 | Investment, economy, planning, financial investments, financial concern, difficulty in investment, economic challenges, economic opportunities, cost optimisation, risk of financial loss, financial evaluation, financial investment, financial planning |

| Agriculture | 31 | Agriculture |

| Public finances | 25 | Public finances, challenges of rural extension, distrust in public policies, criticism of government financial subsidies, rural transformation, financial aid, financial incentive, government financing |

| Sustainability | 20 | Sustainability, environmental sustainability, environment/animal protection, environmental preservation, environment |

| Uncertainty/risks | 20 | Uncertainty, insecurity, security, challenge, risk, scepticism |

| Market and business development | 17 | Business development, market, market difficulties, entry barriers, risk of financial loss, financial, financial difficulty, business growth, financial market, business plans, market development, market view |

| Entrepreneurship | 15 | Entrepreneurship |

| Socioeconomic challenges | 11 | Socioeconomic challenges |

| Technology/innovation | 11 | Technology, innovation |

| Participation | 8 | Participation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bogueva, D.; Marques, M.; Molento, C.F.M.; Marinova, D.; Phillips, C.J.C. Will the Cows and Chickens Come Home? Perspectives of Australian and Brazilian Beef and Poultry Farmers towards Diversification. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12380. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612380

Bogueva D, Marques M, Molento CFM, Marinova D, Phillips CJC. Will the Cows and Chickens Come Home? Perspectives of Australian and Brazilian Beef and Poultry Farmers towards Diversification. Sustainability. 2023; 15(16):12380. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612380

Chicago/Turabian StyleBogueva, Diana, Maria Marques, Carla Forte Maiolino Molento, Dora Marinova, and Clive J. C. Phillips. 2023. "Will the Cows and Chickens Come Home? Perspectives of Australian and Brazilian Beef and Poultry Farmers towards Diversification" Sustainability 15, no. 16: 12380. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612380

APA StyleBogueva, D., Marques, M., Molento, C. F. M., Marinova, D., & Phillips, C. J. C. (2023). Will the Cows and Chickens Come Home? Perspectives of Australian and Brazilian Beef and Poultry Farmers towards Diversification. Sustainability, 15(16), 12380. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612380