Beyond Smart: How ICT Is Enabling Sustainable Cities of the Future

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the issues in the alignment of ICT with sustainability in city projects?

- (2)

- How do different stakeholders’ interests in ICT and sustainability vary in the city context?

- (3)

- What are the key roles in the alignment of ICT with sustainability in city projects?

2. Research Background

2.1. Smart Cities

2.2. The Problems of the Smart Cities Discourse

2.3. ICT and Sustainability

3. Materials and Methods

- Issues in supporting sustainability through ICT in the smart city context;

- Different levels of interest/priority in ICT and sustainability;

- Key roles in ICT for sustainability.

3.1. Selecting Participants

3.2. Analysing the Interview Data

4. Results

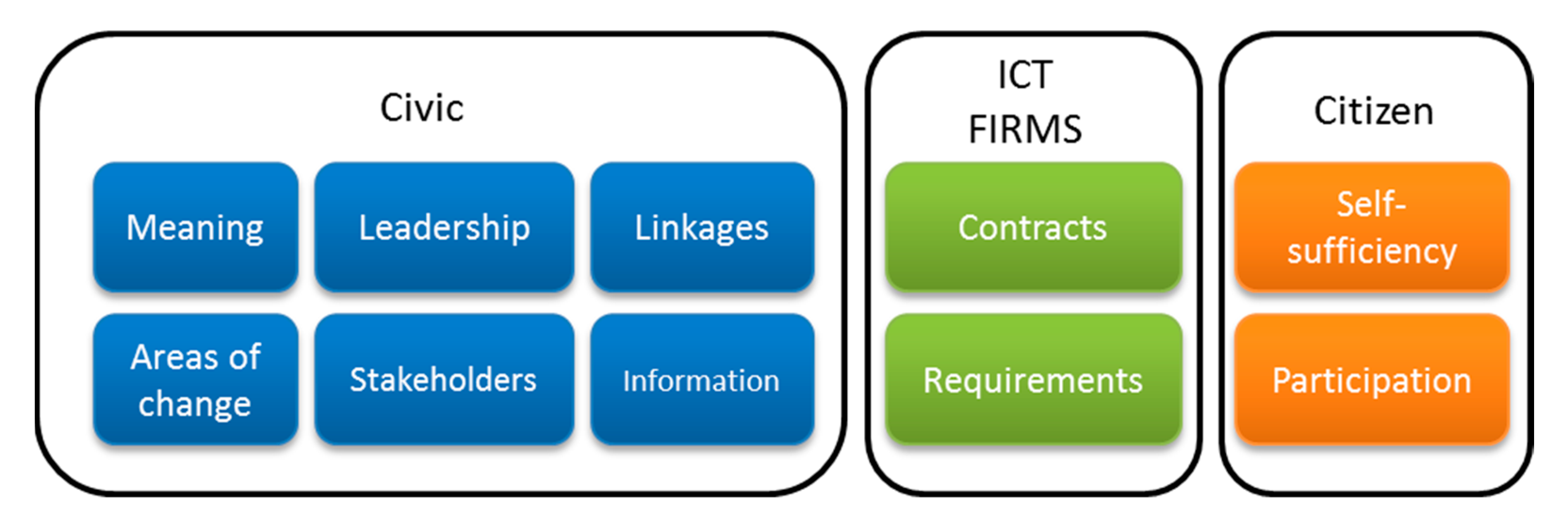

4.1. The Civic Elements of Knowing

- (1)

- Knowing what is meant by smart and sustainable

- (2)

- Knowing who is leading

- (3)

- Knowing how things fit together

‘European funds are difficult to access, and the enforced cross European aspect makes that local emphasis difficult when actually you want to make it work in your city, your neighbourhood and your district’.

‘…we are talking about 60,000 homes to be retrofitted over 8 years. But when the city has got over 450,000 homes there is still an awful lot to be done… So the challenge with the carbon road map is both to celebrate that we’ve started a substantial journey but also at what point do we build up and accelerate the programme?’

- (4)

- Knowing what needs to change

- (5)

- Knowing who needs to be involved

‘…you have, for instance, the Science Park, … you’ll have the city council and the local enterprise partnership… and you’ll have another board which is Creative City Partnerships. Each of those are looking to do different things around skills and enterprise, but there are a lot of potential crossovers. How do you actually get the benefit of that synergy? ’.(Participant 8)

- (6)

- Knowing through data and information

‘So this discussion is going on saying we need to have a view on what happens when all these people are providing council services, but are not part of the council, because they’re using data and information. And that data and information, one, it may be our legal responsibility anyway so that is an issue, and secondly, even where it isn’t, that’s a value to us because there’s several uses for that, one is the analytical and the understanding about that when you’re trying to push services together’.(Participant 4)

- (7)

- Summary

4.2. The ICT Firm-Related Themes

- (1)

- Knowing the impact of contracts

‘…we are funded to support their IT systems and we respond to change that is required within the city. We also have a responsibility to help drive innovation in the city, so identifying where there are opportunities; and those opportunities may be cost saving, improvement to service, sustainability’.(Participant 2)

- (2)

- Knowing the sustainability requirements

- (3)

- Summary

4.3. The Citizen

- (1)

- Knowing for self-sufficiency

‘You’ve got the city Energy Savers that are going out and doing their retrofits and going into social housing, especially when they’re touching where there’s fuel poverty, how do you link that into social care services? How are you collecting/aggregating that information that sits out there from people that go into people’s homes?’

‘But I think it’s trying to focus the conversation on something that’s relevant to them… Because it’s their understanding, and I think a lot of is around education, you have to understand where they’re coming from and then start to understand what the issues are for them, then you can start to then talk to them about how data, information or technology could make a difference’.(Participant 8)

- (2)

- Knowing for participation

‘I’d say you need a proxy set of translators. In a social sustainable project rather than an environmental sustainable project we work with proxies. So, we will find somebody in say the city Carer Centre—people have nothing to do with IT, …—we use those people to engage with the actual carer to ask them to work with them’.(Participant 7)

- (3)

- Summary

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Clarify Meaning

5.2. Demonstrate Strong Leadership

5.3. Create Linkages

5.4. Focus on Key Areas of Change

5.5. Involve Stakeholders

5.6. Leverage Information

5.7. Rethink Contracts

5.8. Embed Sustainability in ICT Requirements

5.9. Enable Self-Sufficiency

5.10. Enable Participation

5.11. Research Limitations and Recommendations for Further Research

5.12. Policy Implications of This Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maja, M.M.; Ayano, S.F. The Impact of Population Growth on Natural Resources and Farmers’ Capacity to Adapt to Climate Change in Low-Income Countries. Earth Syst. Environ. 2021, 5, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Amorim, W.S.; Borchardt Deggau, A.; do Livramento Gonçalves, G.; da Silva Neiva, S.; Prasath, A.R.; de Andrade, J.B.S. Urban challenges and opportunities to promote sustainable food security through smart cities and the 4th industrial revolution. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). World Urbanization Prospects—The 2011 Revision; Population Division, Population Estimates and Projections Section: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Cities and Climate Change|UNEP—UN Environment Programme; UN Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2009; Available online: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/resource-efficiency/what-we-do/cities/cities-and-climate-change (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Tan, S.Y.; Taeihagh, A. Smart City Governance in Developing Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mills, D.; Pudney, S.; Pevcin, P.; Dvorak, J. Evidence-Based Public Policy Decision-Making in Smart Cities: Does Extant Theory Support Achievement of City Sustainability Objectives? Sustainability 2021, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lom, M.; Pribyl, O. Smart city model based on systems theory. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 56, 102092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojdani, A. Smart Integration. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2008, 6, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, J.; Fietkiewicz, K.; Gremm, J. Informational Urbanism. A Conceptual Framework of Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Allwinkle, S.; Cruickshank, P. Creating Smart-er Cities: An Overview. J. Urban Technol. 2011, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony Jnr, B. Managing digital transformation of smart cities through enterprise architecture—A review and research agenda. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2020, 15, 299–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosannenzadeh, F.; Vettorato, D. Defining Smart City. A Conceptual Framework Based on Keyword Analysis. TeMA-J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2014, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, R.M.; Litow, S.S.; School, H.B. Informed and Interconnected: A Manifesto for Smarter Cities Informed and Interconnected: A Manifesto for Smarter Cities; Harvard Business School General Management Unit Working Paper; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, M.M.; Hackney, R.; Ali, M. Facilitating enterprise application integration adoption: An empirical analysis of UK local government authorities. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I.; Kim, S.; Choi, S.; Kim, D.; Choi, Y.; Kim, D.; Ni, Y.; Yin, J. Identifying Key Elements for Establishing Sustainable Conventions and Exhibitions: Use of the Delphi and AHP Approaches. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, H. Developing a human perspective to the digital divide in the “smart city”. In Proceedings of the Australian Library and Information Association Biennial Conference, Broadbeach, QLD, Australia, 21–24 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rios, P. Creating “The Smart City”. University of Detroit Mercy Dissertation, Thesis, and Student Project Collections. 2012. Available online: https://archive.udmercy.edu/handle/10429/393 (accessed on 13 May 2023).

- Nam, T.; Pardo, T.A. Conceptualizing smart city with dimensions of technology, people, and institutions. In Proceedings of the 12th Annual International Digital Government Research Conference on Digital Government Innovation in Challenging Times —Dg.o ’11, College Park, MD, USA, 12–15 June 2011; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; p. 282. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, U. Surely There’s a Smarter Approach to Smart Cities?|WIRED UK; Wired.co.uk. 2012. Available online: https://www.wired.co.uk/article/potential-of-smarter-cities-beyond-ibm-and-cisco (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Chourabi, H.; Nam, T.; Walker, S.; Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Mellouli, S.; Nahon, K.; Pardo, T.A.; Scholl, H.J. Understanding Smart Cities: An Integrative Framework. In Proceedings of the 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2012; pp. 2289–2297. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, S. What Is a Smart City? Definition from WhatIs.com. Tech Target. 2020. Available online: https://www.techtarget.com/iotagenda/definition/smart-city (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Javidroozi, V.; Shah, H.; Feldman, G. A framework for addressing the challenges of business process change during enterprise systems integration. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2019, 26, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myeong, S.; Park, J.; Lee, M. Research Models and Methodologies on the Smart City: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carswell, A.T. The Encyclopedia of Housing; SAGE Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bilali, H.; Bottalico, F.; Ottomano Palmisano, G.; Capone, R. Information and communication technologies for smart and sustainable agriculture. IFMBE Proc. 2020, 78, 321–334. [Google Scholar]

- Javidroozi, V.; Shah, H.; Feldman, G. Urban Computing and Smart Cities: Towards Changing City Processes by Applying Enterprise Systems Integration Practices. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 108023–108034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffers, H.; Komninos, N.; Pallot, M. Smart Cities as Innovation Ecosystems Sustained by the Future Internet. 2012. Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwib6oTw0d2AAxWKpVYBHRlRCgAQFnoECBsQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fhal.inria.fr%2Fhal-00769635&usg=AOvVaw0NbtFFGGXjlUjGKJJXGV2R&opi=89978449 (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Browne, N.J.W. Regarding Smart Cities in China, the North and Emerging Economies—One Size Does Not Fit All. Smart Cities 2020, 3, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esposito, G.; Clement, J.; Mora, L.; Crutzen, N. One size does not fit all: Framing smart city policy narratives within regional socio-economic contexts in Brussels and Wallonia. Cities 2021, 118, 103329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollands, R.G. Will the real smart city please stand up? City 2008, 12, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toli, A.M.; Murtagh, N. The Concept of Sustainability in Smart City Definitions. Front. Built Environ. 2020, 6, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Jayasena, N.S.; Mallawaarachchi, H.; Waidyasekara, K.G. Stakeholder Analysis For Smart City Development Project: An Extensive Literature Review. MATEC Web Conf. 2019, 266, 06012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zafar, S.Z.; Zhilin, Q.; Mabrouk, F.; Ramirez-Asis, E.; Alzoubi, H.M.; Hishan, S.S.; Michel, M. Empirical linkages between ICT, tourism, and trade towards sustainable environment: Evidence from BRICS countries. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2022, 36, 2127417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bifulco, F.; Tregua, M.; Amitrano, C.C.; D’Auria, A. ICT and sustainability in smart cities management. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2016, 29, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.; Ansari, S.; Castro, F.; Chakra, R.; Hassan, B.H.; Krüger, C.; Babazadeh, D.; Lehnhof, S. A framework for the integration of ICT-relevant data in power system applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Milan PowerTech, Milan, Italy, 23–27 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilty, L.M.; Arnfalk, P.; Erdmann, L.; Goodman, J.; Lehmann, M.; Wäger, P.A. The relevance of information and communication technologies for environmental sustainability—A prospective simulation study. Environ. Model. Softw. 2006, 21, 1618–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Lee, C.C.; Song, Z. Digitalization and environment: How does ICT affect enterprise environmental performance? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 54826–54841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antrobus, D. Smart green cities: From modernization to resilience? Urban Res. Pract. 2011, 4, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peris-Ortiz, M.; Bennett, D.R.; Yábar, D.P.B. Sustainable Smart Cities; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, T.; Pardo, T.A. Smart city as urban innovation: Focusing on management, policy, and context. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance—ICEGOV ’11, Beijing, China, 25–28 October 2010; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; p. 185. [Google Scholar]

- Petrini, M.; Pozzebon, M. Managing sustainability with the support of business intelligence: Integrating socio-environmental indicators and organisational context. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2009, 18, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naphade, M.; Banavar, G.; Harrison, C.; Paraszczak, J.; Morris, R. Smarter Cities and Their Innovation Challenges. Computer 2011, 44, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banday, U.J.; Aneja, R. Renewable and non-renewable energy consumption, economic growth and carbon emission in BRICS: Evidence from bootstrap panel causality. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2020, 14, 248–260. [Google Scholar]

- Appio, F.P.; Lima, M.; Paroutis, S. Understanding Smart Cities: Innovation ecosystems, technological advancements, and societal challenges. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 142, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, B.; Wilhelmer, D.; Palensky, P. Smart buildings, smart cities and governing innovation in the new millennium. In Proceedings of the 2010 8th IEEE International Conference on Industrial Informatics, Osaka, Japan, 13–16 July 2010; pp. 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartelt, V.L.; Urbaczewski, A.; Mueller, A.G.; Sarker, S. Enabling collaboration and innovation in Denver’s smart city through a living lab: A social capital perspective. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M.; Axhausen, K.W.; Giannotti, F.; Pozdnoukhov, A.; Bazzani, A.; Wachowicz, M.; Ouzounis, G.; Portugali, Y. Smart cities of the future. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2012, 214, 481–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Javidroozi, V.; Shah, H.; Feldman, G. Facilitating Smart City Development through Adaption of the Learnings from Enterprise Systems Integration. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendybayev, B. Imbalances in Kazakhstan’s Smart Cities Development. Environ. Urban. ASIA 2022, 13, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, G. COVID-19 and the digital divide in the UK. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, e395–e396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, N. Empowerment through participation in local governance: The case of Union Parishad in Bangladesh. Public Adm. Policy 2019, 22, 40–54. [Google Scholar]

- Desouza, K.C.; Bhagwatwar, A. Citizen Apps to Solve Complex Urban Problems. J. Urban Technol. 2012, 19, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Definition | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| [16] | A city where ICT strengthens the freedom of speech and the accessibility to public information and services. | ICT focus on freedom of speech, information and services |

| [17] | A city that gives inspiration, and shares culture, knowledge, and life, a city that motivates its inhabitants to create and flourish their own lives. | People-focused—improve lives through culture and knowledge |

| [18] | A smart city looks at all the exchanges of information that flow between its many different subsystems. It then analyses this flow of information, as well as of services, and acts upon it in order to make its wider ecosystem more resource-efficient and sustainable. | Information for services, resource efficiency, sustainability |

| [19] | Any adequate model for the smart city must focus on the smartness of its citizens and encourage the processes that make cities important: those that sustain very different—sometimes conflicting—activities. Cities are, by definition, engines of diversity; so, focusing solely on streamlining utilities, transport, construction and unseen government processes can be massively counter-productive, in much the same way that the 1960s idealistic fondness for social-housing tower-block economic efficiency was found, ultimately, to be socially and culturally unsustainable. | Citizen-focused, efficiency, diversity |

| [20] | Their smart cities framework consists of eight clusters of factors: management and organisation, technology, governance, policy, people and communities, the economy, built infrastructure and the natural environment. | Management/organisation, technology, governance, policy, people, economy, infrastructure and environment |

| [21] | The smart city is a territory with a high capacity for learning innovations, built on the creativity of its residents, their knowledge development, and their digital infrastructure for communications and knowledge management. | Citizen/community-focused, digital technologies and infrastructure |

| [22] | A system of systems in which cross-sectoral city system integration has been accomplished, enabling access to real-time information and knowledge by all the city sectors, providing integrated services, and enhancing liveability, workability, and sustainability for the citizens. | Systems integration, connectivity or the processes and data, future sustainable cities |

| [23] | A smart city is a sustainable city that solves urban problems and improves citizens’ quality of life through the fourth industrial revolution, technology and governance between stakeholders | Smart sustainable cities, industry 4.0, governance and digital technology |

| Participant | Participant Type |

|---|---|

| Participant 1 | Strategic Development |

| Participant 2 | ICT Innovation |

| Participant 3 | ICT Solutions |

| Participant 4 | Information Strategy |

| Participant 5 | Environmental Sustainability Strategy |

| Participant 6 | ICT Strategy |

| Participant 7 | ICT Strategy |

| Participant 8 | ICT Strategy |

| Participant 9 | Pilot (Sustainability and Technology Expert) |

| Participant 10 | Pilot (ICT Expert/Advisor to Local Governments) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shah, H. Beyond Smart: How ICT Is Enabling Sustainable Cities of the Future. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12381. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612381

Shah H. Beyond Smart: How ICT Is Enabling Sustainable Cities of the Future. Sustainability. 2023; 15(16):12381. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612381

Chicago/Turabian StyleShah, Hanifa. 2023. "Beyond Smart: How ICT Is Enabling Sustainable Cities of the Future" Sustainability 15, no. 16: 12381. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612381

APA StyleShah, H. (2023). Beyond Smart: How ICT Is Enabling Sustainable Cities of the Future. Sustainability, 15(16), 12381. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612381