Analyst Coverage and Corporate ESG Performance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Literature Review on Corporate ESG

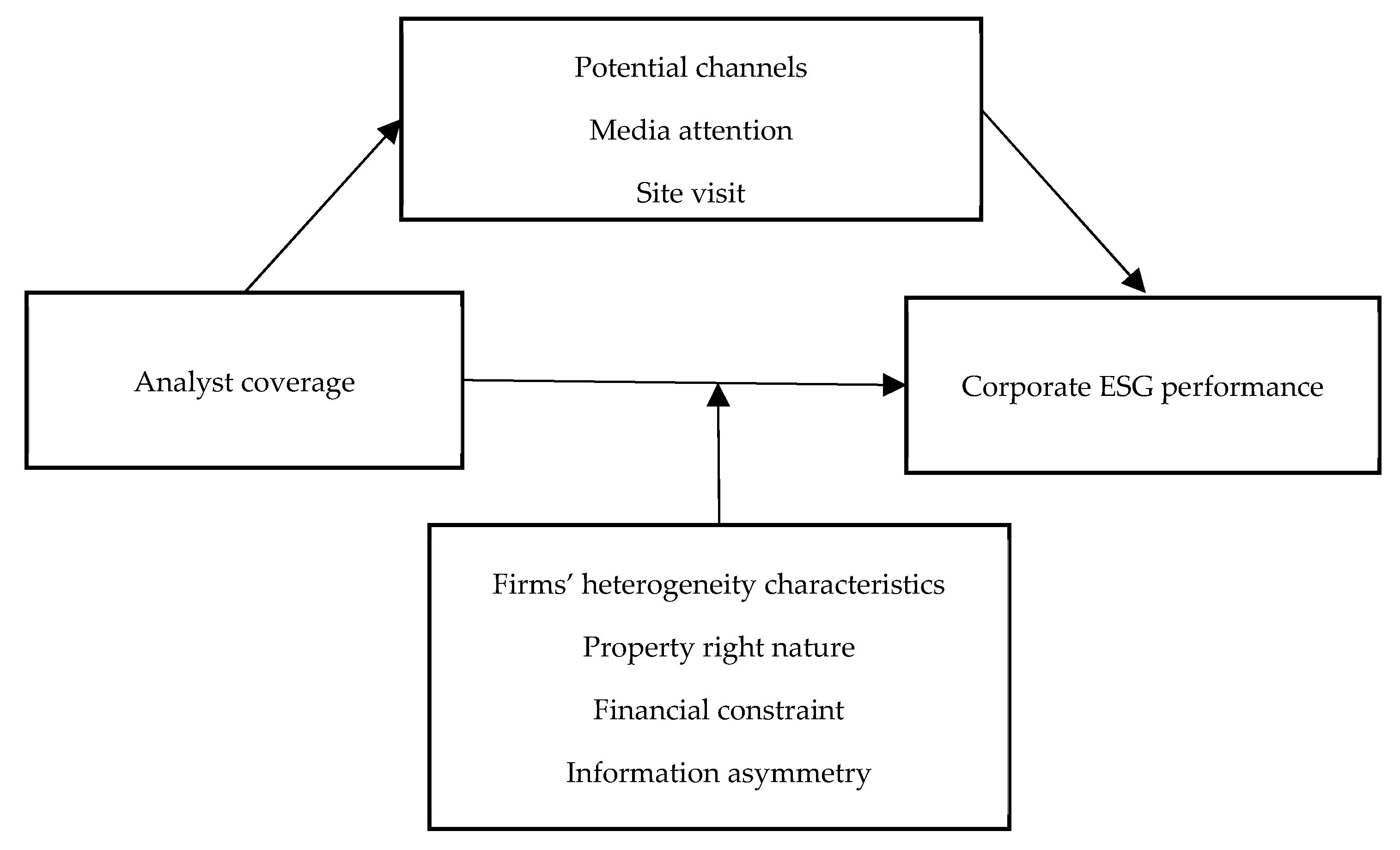

2.2. Analyst Coverage and Corporate ESG Performance

3. Data and Model Design

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Research Model

3.3. Variables

3.3.1. Dependent Variables

3.3.2. Independent Variables

3.3.3. Control Variables

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Correlation Analysis

4.3. Main Regression Results

4.4. Robustness Tests

4.4.1. IV 2sls

4.4.2. Entropy Balance Matching Method

4.5. Change Variable Measurement and Sample Selection

4.5.1. Alternative Measurement of the Independent Variables

4.5.2. Alternative Measurement of the Dependent Variable

4.5.3. Lag All Explanatory Variables

4.5.4. Drop Sample without Analyst Coverage

5. Further Research

5.1. Test Based on the Firms’ Heterogeneity Characteristics

5.1.1. Test Based on the Firms’ Property Rights

5.1.2. Test Based on Firms’ Financial Constraints

5.1.3. Test Based on Firms’ Information Asymmetry

5.2. Potential Channels

5.2.1. Potential Channel—Media Attention

5.2.2. Potential Channel—Site Visit

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Main Conclusions

6.2. Implications

- (1)

- The role analysts play in corporate governance should be fully valued. Analyst attention to corporate non-financial information should not be ignored, and although analyst coverage may put pressure on management, our findings proved that analyst coverage plays a positive role in promoting firms’ sustainability development in an emerging markets scenario.

- (2)

- Firms should pay attention to and improve their ESG performance by establishing a sound ESG framework and making more investments in ESG activities, thereby promoting their sustainable development. Furthermore, good information transparency provides an opportunity for outsiders to understand the real ESG performance of enterprises. Companies should increase the degree of ESG information disclosure to the authoritative ESG framework and show details of the real ESG performance of the company to outsiders.

- (3)

- For investors, the non-financial information of an enterprise also has value and contains information. Investors should take the ESG performance of enterprises into account when selecting investment targets. This can not only reduce investment risks and increase investment return, but can also promote the sustainable development of society.

- (4)

- From the perspective of regulators, policy makers should create favorable policies and laws for ESG construction in firms, and encourage firms to actively participate in ESG development within the formal system. First, regulated policy should consider firms’ property rights and financing constraints, use market incentives to guide non-state-owned enterprises to participate in ESG construction, and carry out financing reform and expand financing channels for enterprises to address the difficulty and high cost of financing for non-state-owned enterprises. Regulators should have a rational view of the role analysts play in influencing the development of corporate ESG as an informal institution, strengthen the supervision of analysts, and guide analysts to participate more effectively in corporate governance.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Husted, B.W.; de Sousa, J.M. Board structure and environmental, social, and governance disclosure in Latin America. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 102, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Le, Q.Q.; Peng, M.R.; Zeng, H.X.; Kong, L.Y. Does central environmental protection inspection improve corporate environmental, social, and governance performance? Evidence from China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.; Tan, W.Q. Does carbon control policy risk affect corporate ESG performance? Econ. Model. 2023, 120, 106148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambrea, D.R.; Paolone, F.; Cucari, N. Advisory or monitoring role in ESG scenario: Which women directors are more influential in the Italian context? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 122125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Wan, H.; Wang, B.; Yang, T.N. Institutional Investors and Corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance Policies: Evidence from Toxics Release Data. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 4901–4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, D.S.; Radhakrishnan, S.; Tsang, A.; Yang, Y.G. Nonfinancial Disclosure and Analyst Forecast Accuracy: International Evidence on Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure. Account. Rev. 2012, 87, 723–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, K.; Gupta, J. Stranded assets and stranded resources: Implications for climate change mitigation and global sustainable development. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 56, 101215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Wu, S.R. Corporate sustainability and analysts’ earnings forecast accuracy: Evidence from environmental, social and governance ratings. Corp. Soc. Resp. Env. Manag. 2022, 29, 1465–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, M.; Mirza, N.; Rizvi, S.K.A.; Naqvi, B. ESG scores and target price accuracy: Evidence from sell-side recommendations in BRICS. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 84, 102389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiemann, F.; Tietmeyer, R. ESG Controversies, ESG Disclosure and Analyst Forecast Accuracy. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 84, 102373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, M.; Dal Maso, L.; Liberatore, G.; Mazzi, F.; Terzani, S. Role of Country- and Firm-Level Determinants in Environmental, Social, and Governance Disclosure. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.P.; Li, Y.J.; Lin, M.M.; McBrayer, G.A. Natural disasters, risk salience, and corporate ESG disclosure*. J. Corp. Financ. 2022, 72, 102152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barko, T.; Cremers, M.; Renneboog, L. Shareholder Engagement on Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 180, 777–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBrayer, G.A. Does persistence explain ESG disclosure decisions? Corp. Soc. Resp. Env. Manag. 2018, 25, 1074–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kind, F.L.; Zeppenfeld, J.; Lueg, R. The impact of chief executive officer narcissism on environmental, social, and governance reporting. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, T.Y.; Navone, M.; Wu, E. Analyst coverage and the quality of corporate investment decisions. J. Corp. Financ. 2018, 51, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.B.; Kim, Y.; Lee, J. Analyst reputation and management earnings forecasts. J. Account. Public Pol. 2021, 40, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Feng, X.; Tang, S.L. Do site visits mitigate corporate fraudulence? Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, 78, 101940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Tong, L.J.; Su, J.; Cui, Z.P. Analyst coverage and corporate social performance: Evidence from China. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2015, 32, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, D.; Mao, C.X.; Zhang, C. Does Analyst Coverage Affect Workplace Safety? Manag. Sci. 2022, 68, 3464–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, C.; Keasey, K.; Lim, I.; Xu, B. Analyst Coverage and Corporate Environmental Policies. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. Forthcom. 2022, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.H.; Wang, C.; Li, S.; Wan, J. Do institutional investors’ corporate site visits improve ESG performance? Evidence from China. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2022, 76, 101884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Du, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.T. Seeing is believing: Analysts’ corporate site visits. Rev. Account. Stud. 2016, 21, 1245–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Quan, X.F.; Xu, X.M. Under watchful eyes: Analyst site visits and firm earnings management. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 83, 102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, M.R. Financing Conditions and Toxic Emissions; SAFE Working Paper No. 254; Leibniz Institute for Financial Research SAFE: Frankfurt, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, R.J.; Shen, W. The impacts of performance relative to analyst forecasts and analyst coverage on firm R&D intensity. Strategy Manag. J. 2013, 34, 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Dyck, A.; Morse, A.; Zingales, L. Who Blows the Whistle on Corporate Fraud? J. Financ. 2010, 65, 2213–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Harford, J.; Lin, C. Do analysts matter for governance? Evidence from natural experiments. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 115, 383–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F. Analyst coverage and earnings management. J. Financ. Econ. 2008, 88, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irani, R.M.; Oesch, D. Analyst Coverage and Real Earnings Management: Quasi-Experimental Evidence. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2016, 51, 589–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan-Hussin, W.N.; Qasem, A.; Aripin, N.; Ariffin, M.S.M. Corporate Responsibility Disclosure, Information Environment and Analysts’ Recommendations: Evidence from Malaysia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, U.; Hirshleifer, D. Shared analyst coverage: Unifying momentum spillover effects. J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 136, 649–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amosh, H.; Khatib, S.F.A.; Ananzeh, H. Terrorist attacks and environmental social and governance performance: Evidence from cross-country panel data. Corp. Soc. Resp. Env. Manag. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulimany, H.G.H. Ownership structure and audit report lag of Saudi listed firms: A dynamic panel analysis. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2229105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Analyst coverage and corporate social responsibility decoupling: Evidence from China. Corp. Soc. Resp. Env. Manag. 2022, 29, 620–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Xiong, W.F.; Xu, C. Analyst coverage, corporate social responsibility, and firm value: Evidence from China. Glob. Financ. J. 2021, 50, 100671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hainmueller, J. Entropy balancing for causal effects: A multivariate reweighting method to produce balanced samples in observational studies. Political Anal. 2012, 20, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.Y. State Ownership and Target Setting: Evidence from Publicly Listed Companies in China. Contemp. Account. Res. 2021, 38, 1925–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Siegel, D.S.; Waldman, D.A. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Sustainability. Bus. Soc. 2011, 50, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.W.; Gong, M.F.; Zhang, X.Y.; Koh, L. The impact of environmental, social, and governance disclosure on firm value: The role of CEO power. Br. Account. Rev. 2018, 50, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.P.; Kim, T. Financial Constraints and Corporate Environmental Policies. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2022, 35, 576–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, R.C.; Chatfield, R.E.; Sisneros, P.M. Security Analyst Monitoring Activity—Agency Costs and Information Demands. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 1989, 24, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrien, F.; Kecskes, A.; Mansi, S.A. Information asymmetry, the cost of debt, and credit events: Evidence from quasi-random analyst disappearances. J. Corp. Financ. 2016, 39, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallman, N.; Howe, J.S.; Wang, W. Analyst coverage and syndicated lending. Rev. Account. Stud. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadlock, C.J.; Pierce, J.R. New Evidence on Measuring Financial Constraints: Moving beyond the KZ Index. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2010, 23, 1909–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.; Ljungqvist, A. Testing Asymmetric-Information Asset Pricing Models. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2012, 25, 1366–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellul, A.; Panayides, M. Do financial analysts restrain insiders’ informational advantage? J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2018, 53, 203–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrien, F.; Kecskes, A. The Real Effects of Financial Shocks: Evidence from Exogenous Changes in Analyst Coverage. J. Financ. 2013, 68, 1407–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, A.P.; Marcus, A.J.; Tehranian, H. Opaque financial reports, R2, and crash risk. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 94, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechow, P.; Ge, W.L.; Schrand, C. Understanding earnings quality: A review of the proxies, their determinants and their consequences. J. Account. Econ. 2010, 50, 344–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.L.; Parwada, J.T.; Zhang, B.H. The Governance Effect of the Media’s News Dissemination Role: Evidence from Insider Trading. J. Account. Res. 2015, 53, 331–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deephouse, D.L. Media reputation as a strategic resource: An integration of mass communication and resource-based theories. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 1091–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Y.; Luo, X.W.; Lu, W.Z. Public perceptions of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) based on social media data: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 387, 135840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.J. Do Boards Take Environmental, Social, and Governance Issues Seriously? Evidence from Media Coverage and CEO Dismissals. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 176, 647–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Tong, L.; Viswanath, P.V.; Zhang, Z. Word Power: The Impact of Negative Media Coverage on Disciplining Corporate Pollution. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 437–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Tang, J.T. Can the Media Discipline Chinese Firms’ Pollution Behaviors? The Mediating Effects of the Public and Government. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1700–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Montgomery, A.W. Tweetjacked: The Impact of Social Media on Corporate Greenwash. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednar, M.K. Watchdog or Lapdog? A Behavioral View of the Media as a Corporate Governance Mechanism. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Du, F.; Wang, B.Y.T.; Wang, X. Do Corporate Site Visits Impact Stock Prices? Contemp. Account. Res. 2019, 36, 359–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.; Sanderson, P.; Barker, R.; Hendry, J. In the mirror of the market: The disciplinary effects of company/fund manager meetings. Account. Org. Soc. 2006, 31, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.Q.; Ma, Y.J.; Martin, X.M.; Michaely, R. On the fast track: Information acquisition costs and information production. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 143, 794–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.H.; Lehavy, R.; Zang, A.Y.; Zheng, R. Analyst Information Discovery and Interpretation Roles: A Topic Modeling Approach. Manag. Sci. 2018, 64, 2833–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.Y.; Yuan, Q.B. Institutional investors’ corporate site visits and corporate innovation. J. Corp. Financ. 2018, 48, 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.W.; Li, J.J.; Lin, B.X. Corporate site visit and tax avoidance: The effects of monitoring and tax knowledge dissemination. J. Corp. Financ. 2023, 79, 102385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Industry Name | Industry Classification Code | Frequency | Percentage (100%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fisheries | A | 145 | 1.38 |

| Extractive industry | B | 458 | 4.37 |

| Textiles, clothing, fur | C1 | 727 | 6.93 |

| Wood, furniture | C2 | 1789 | 17.05 |

| Papermaking and printing | C3 | 3494 | 33.30 |

| Petroleum, chemicals, plastics, and plastics | C4 | 108 | 1.03 |

| Electricity, gas, and water production and supply industry | D | 537 | 5.12 |

| Construction industry | E | 301 | 2.87 |

| Transportation, storage industry | F | 622 | 5.93 |

| Information technology industry | G | 491 | 4.68 |

| Wholesale and retail trade | H | 28 | 0.27 |

| Information transmission, software, and information technology services | I | 607 | 5.79 |

| Real estate | K | 588 | 5.60 |

| Leasing and business service | L | 127 | 1.21 |

| Scientific research and technical services | M | 61 | 0.58 |

| Water, environment, and utilities management | N | 84 | 0.80 |

| Total | 10,491 | 100 |

| Variable Category | Variable Symbol | Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | ESG | The firm’s ESG disclosure score from Bloomberg |

| E | The firm’s environment disclosure score from Bloomberg | |

| S | The firm’s social disclosure score from Bloomberg | |

| G | The firm’s governance disclosure score from Bloomberg | |

| Independent variables | Cov1 | The annual analyst coverage number for firm i in year t |

| Cov2 | The annual number of earning forecasts for firm i in year t | |

| Control variables | Size | Natural log of total assets |

| Lev | Total liabilities divided by total assets | |

| Inst | The percentage of institutional ownership | |

| ROA | Net income divided by total assets in year t | |

| Growth | The annual revenue growth rate | |

| Age | Natural log of the years since the firm listing year to fiscal year t | |

| State | 1 if a company is state-owned, otherwise 0 | |

| Big1 | The percentage of the largest shareholder holdings | |

| Dual | 1 if the chairman and CEO are the same, otherwise 0 | |

| Indep | The percentage of independent directors |

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | Min | Median | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | 10,289 | 28.681 | 8.873 | 6.198 | 27.643 | 68.917 |

| Cov1 | 10,289 | 11.616 | 12.331 | 0.000 | 7.000 | 51.000 |

| Cov2 | 10,289 | 25.558 | 31.150 | 0.000 | 13.000 | 141.000 |

| E | 10,244 | 12.580 | 7.009 | 0.000 | 10.399 | 54.386 |

| S | 10,194 | 9.291 | 12.544 | 0.000 | 2.416 | 73.815 |

| G | 10,259 | 64.712 | 13.682 | 26.786 | 69.296 | 96.117 |

| Size | 10,289 | 23.233 | 1.311 | 20.484 | 23.115 | 26.973 |

| Lev | 10,289 | 0.478 | 0.199 | 0.067 | 0.490 | 0.886 |

| Inst | 10,289 | 0.505 | 0.217 | 0.001 | 0.524 | 0.885 |

| ROA | 10,289 | 0.044 | 0.059 | −0.184 | 0.038 | 0.219 |

| Growth | 10,289 | 0.166 | 0.370 | −0.498 | 0.107 | 2.238 |

| state | 10,289 | 0.509 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Age | 10,289 | 13.409 | 7.146 | 0.000 | 14.000 | 31.000 |

| Big1 | 10,289 | 0.370 | 0.161 | 0.083 | 0.356 | 0.774 |

| Dual | 10,289 | 0.782 | 0.413 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Indep | 10,289 | 0.376 | 0.057 | 0.182 | 0.364 | 0.800 |

| ESG | E | S | G | Cov1 | Cov2 | Size | Lev | Inst | ROA | Growth | State | Age | Big1 | Dual | Indep | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| E | 0.607 *** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| S | 0.844 *** | 0.610 *** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| G | 0.764 *** | 0.213 *** | 0.352 *** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Cov1 | 0.177 *** | 0.180 *** | 0.196 *** | 0.073 *** | 1 | |||||||||||

| Cov2 | 0.180 *** | 0.179 *** | 0.194 *** | 0.079 *** | 0.954 *** | 1 | ||||||||||

| Size | 0.456 *** | 0.291 *** | 0.361 *** | 0.345 *** | 0.221 *** | 0.225 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| Lev | 0.072 *** | 0.021 ** | 0.043 *** | 0.050 *** | −0.117 *** | −0.102 *** | 0.504 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| Inst | 0.203 *** | 0.127 *** | 0.163 *** | 0.145 *** | 0.196 *** | 0.189 *** | 0.387 *** | 0.139 *** | 1 | |||||||

| ROA | 0.051 *** | 0.064 *** | 0.072 *** | 0.003 | 0.439 *** | 0.417 *** | −0.085 *** | −0.463 *** | 0.112 *** | 1 | ||||||

| Growth | 0.044 *** | −0.008 | 0.036 *** | 0.029 *** | 0.137 *** | 0.137 *** | 0.018 * | −0.005 | −0.040 *** | 0.237 *** | 1 | |||||

| State | 0.078 *** | 0.074 *** | 0.046 *** | 0.038 *** | −0.150 *** | −0.150 *** | 0.276 *** | 0.216 *** | 0.319 *** | −0.179 *** | −0.126 *** | 1 | ||||

| Age | 0.174 *** | −0.030 *** | 0.060 *** | 0.220 *** | −0.226 *** | −0.202 *** | 0.221 *** | 0.231 *** | 0.137 *** | −0.199 *** | −0.106 *** | 0.355 *** | 1 | |||

| Big1 | 0.026 *** | 0.051 *** | 0.051 *** | −0.019 ** | −0.005 | −0.00600 | 0.222 *** | 0.080 *** | 0.499 *** | 0.086 *** | −0.027 *** | 0.255 *** | −0.054 *** | 1 | ||

| Dual | −0.008 | 0.021 ** | −0.015 | −0.020 ** | −0.105 *** | −0.095 *** | 0.101 *** | 0.086 *** | 0.150 *** | −0.086 *** | −0.068 *** | 0.296 *** | 0.186 *** | 0.097 *** | 1 | |

| Indep | 0.074 *** | 0.049 *** | 0.048 *** | 0.070 *** | 0.056 *** | 0.063 *** | 0.081 *** | 0.016 * | 0.031 *** | 0.015 | 0.001 | 0.008 | −0.010 | 0.071 *** | −0.084 *** | 1 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | E | S | G | ESG | E | S | G | |

| Cov1 | 0.052 *** | 0.051 *** | 0.111 *** | −0.006 | ||||

| (5.401) | (5.163) | (5.651) | (−0.445) | |||||

| Cov2 | 0.018 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.039 *** | −0.002 | ||||

| (5.240) | (4.955) | (5.701) | (−0.449) | |||||

| Size | 1.176 *** | 1.409 *** | 1.902 *** | 0.077 | 1.217 *** | 1.450 *** | 1.986 *** | 0.073 |

| (5.377) | (6.793) | (4.828) | (0.230) | (5.563) | (7.000) | (5.062) | (0.219) | |

| Lev | −2.555 *** | −1.893 *** | −3.020 * | −2.752 ** | −2.612 *** | −1.950 *** | −3.141 ** | −2.745 ** |

| (−3.441) | (−2.649) | (−1.960) | (−2.124) | (−3.517) | (−2.724) | (−2.040) | (−2.119) | |

| Inst | 0.415 | 0.387 | 1.657 * | −0.917 | 0.482 | 0.455 | 1.798 * | −0.923 |

| (0.879) | (0.743) | (1.721) | (−1.213) | (1.021) | (0.871) | (1.873) | (−1.221) | |

| ROA | 2.140 * | 1.660 | 5.233 * | −0.077 | 2.325 * | 1.847 | 5.576 ** | −0.090 |

| (1.651) | (1.272) | (1.959) | (−0.038) | (1.803) | (1.407) | (2.114) | (−0.045) | |

| Growth | −0.057 | −0.172 | −0.204 | 0.182 | −0.075 | −0.189 * | −0.244 | 0.184 |

| (−0.444) | (−1.537) | (−0.844) | (0.898) | (−0.584) | (−1.692) | (−1.010) | (0.910) | |

| State | −0.009 | 0.102 | 0.184 | −0.616 | 0.006 | 0.116 | 0.219 | −0.618 |

| (−0.021) | (0.262) | (0.205) | (−0.683) | (0.015) | (0.298) | (0.247) | (−0.686) | |

| Age | 1.835 *** | 0.461 *** | 1.727 *** | 2.612 *** | 1.820 *** | 0.445 *** | 1.695 *** | 2.614 *** |

| (48.967) | (12.867) | (22.981) | (47.807) | (49.290) | (12.668) | (23.047) | (48.673) | |

| Big1 | 1.712 | 0.456 | 1.829 | 3.310 * | 1.676 | 0.408 | 1.758 | 3.314 * |

| (1.379) | (0.372) | (0.794) | (1.735) | (1.346) | (0.333) | (0.760) | (1.736) | |

| Dual | −0.062 | 0.243 | −0.311 | −0.092 | −0.064 | 0.242 | −0.315 | −0.092 |

| (−0.281) | (1.260) | (−0.672) | (−0.307) | (−0.287) | (1.246) | (−0.679) | (−0.306) | |

| Indep | 3.582 ** | 3.366 ** | 7.708 *** | −1.128 | 3.516 ** | 3.323 ** | 7.550 ** | −1.123 |

| (2.548) | (2.084) | (2.621) | (−0.474) | (2.492) | (2.056) | (2.572) | (−0.472) | |

| Constant | −24.103 *** | −28.182 *** | −59.588 *** | 25.658 *** | −24.678 *** | −28.760 *** | −60.718 *** | 25.715 *** |

| (−5.099) | (−6.201) | (−6.989) | (3.559) | (−5.209) | (−6.323) | (−7.129) | (3.585) | |

| N | 10,289 | 10,244 | 10,194 | 10,259 | 10,289 | 10,244 | 10,194 | 10,259 |

| Year and Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Adj_R2 | 0.691 | 0.274 | 0.362 | 0.731 | 0.691 | 0.273 | 0.362 | 0.731 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cov1 | ESG | Cov2 | ESG | ESG | ESG | |

| IV 2sls | Entropy Balance | |||||

| Ind_Cov | 0.417 *** | 0.941 *** | ||||

| (11.675) | (9.768) | |||||

| Cov1 | 0.327 *** | |||||

| (6.015) | ||||||

| Cov2 | 0.145 *** | |||||

| (5.729) | ||||||

| Treat1 | 0.459 *** | |||||

| (3.338) | ||||||

| Treat2 | 0.574 *** | |||||

| (4.109) | ||||||

| Size | 3.996 *** | 0.087 | 9.064 *** | 0.079 | 1.220 *** | 1.192 *** |

| (19.801) | (0.344) | (16.659) | (0.299) | (6.903) | (6.723) | |

| Lev | 0.080 | −2.681 *** | 3.330 | −3.138 *** | −1.757 ** | −1.701 ** |

| (0.088) | (−4.641) | (1.356) | (−5.113) | (−2.420) | (−2.340) | |

| Inst | 9.222 *** | −2.022 *** | 22.291 *** | −2.238 *** | −0.176 | −0.201 |

| (15.231) | (−3.278) | (13.658) | (−3.304) | (−0.401) | (−0.457) | |

| ROA | 44.288 *** | −10.275 *** | 115.010 *** | −12.466 *** | 4.262 *** | 4.669 *** |

| (23.818) | (−3.770) | (22.945) | (−3.883) | (2.819) | (3.144) | |

| Growth | 0.006 | −0.069 | 1.021 * | −0.215 | 0.114 | 0.109 |

| (0.030) | (−0.532) | (1.840) | (−1.539) | (0.641) | (0.616) | |

| State | −2.062 *** | 0.633 | −6.848 *** | 0.951 ** | −0.052 | −0.047 |

| (−3.442) | (1.581) | (−4.241) | (2.157) | (−0.146) | (−0.133) | |

| Age | −1.592 *** | 2.083 *** | −3.802 *** | 2.037 *** | ||

| (−5.655) | (37.424) | (−5.009) | (39.507) | |||

| Big1 | −7.397 *** | 3.804 *** | −19.015 *** | 4.142 *** | 2.711 ** | 2.669 ** |

| (−5.651) | (4.106) | (−5.390) | (4.141) | (2.320) | (2.287) | |

| Dual | 0.036 | −0.080 | 0.232 | −0.102 | −0.182 | −0.191 |

| (0.135) | (−0.479) | (0.326) | (−0.581) | (−0.975) | (−1.022) | |

| Indep | −0.501 | 3.625 *** | 2.216 | 3.141 ** | 3.731 ** | 3.743 ** |

| (−0.256) | (2.917) | (0.420) | (2.405) | (2.304) | (2.312) | |

| Constant | −63.732 *** | −4.760 | −144.281 *** | −3.336 | −0.350 | 0.171 |

| (−9.600) | (−0.999) | (−8.062) | (−0.641) | (−0.084) | (0.041) | |

| N | 10,284 | 10,284 | 10,284 | 10,284 | 10,243 | 10,243 |

| Year and Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Adj_R2 | 0.0825 | − | 0.0347 | − | 0.847 | 0.847 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | ESG | ESG_HZ | ESG_HZ | F.ESG | F.ESG | ESG | ESG | |

| Cov1 | 0.503 *** | 0.009 *** | 0.062 *** | 0.052 *** | ||||

| (5.597) | (5.548) | (6.237) | (5.250) | |||||

| Cov2 | 0.389 *** | 0.003 *** | 0.021 *** | 0.018 *** | ||||

| (5.492) | (5.092) | (5.800) | (5.143) | |||||

| Size | 1.134 *** | 1.147 *** | 0.244 *** | 0.252 *** | 0.894 *** | 0.954 *** | 0.912 *** | 0.955 *** |

| (5.099) | (5.153) | (6.925) | (7.143) | (3.665) | (3.903) | (3.269) | (3.422) | |

| Lev | −2.348 *** | −2.361 *** | −0.953 *** | −0.962 *** | −1.499 * | −1.579 * | −2.542 *** | −2.607 *** |

| (−3.170) | (−3.188) | (−6.506) | (−6.552) | (−1.732) | (−1.830) | (−2.916) | (−2.993) | |

| Inst | 0.486 | 0.489 | 0.249 *** | 0.262 *** | 0.408 | 0.511 | 0.245 | 0.309 |

| (1.029) | (1.030) | (2.732) | (2.889) | (0.867) | (1.086) | (0.478) | (0.603) | |

| ROA | 2.448 * | 2.437 * | 0.685 ** | 0.728 ** | 4.380 *** | 4.762 *** | 2.348 | 2.516 |

| (1.880) | (1.863) | (2.347) | (2.505) | (2.918) | (3.209) | (1.389) | (1.492) | |

| Growth | −0.074 | −0.088 | −0.076 *** | −0.079 *** | −0.007 | −0.027 | −0.045 | −0.070 |

| (−0.579) | (−0.685) | (−2.748) | (−2.847) | (−0.048) | (−0.198) | (−0.293) | (−0.462) | |

| State | 0.010 | 0.021 | 0.227 ** | 0.229 ** | 0.170 | 0.185 | 0.023 | 0.052 |

| (0.023) | (0.050) | (2.380) | (2.401) | (0.388) | (0.425) | (0.044) | (0.100) | |

| Age | 1.851 *** | 1.845 *** | −0.016 *** | −0.018 *** | 2.064 *** | 2.045 *** | 1.973 *** | 1.957 *** |

| (47.386) | (47.457) | (−2.580) | (−3.058) | (48.730) | (48.825) | (40.978) | (41.059) | |

| Big1 | 1.517 | 1.497 | 0.093 | 0.085 | 2.391 * | 2.312 | 2.426 * | 2.403 * |

| (1.217) | (1.200) | (0.396) | (0.360) | (1.648) | (1.593) | (1.761) | (1.738) | |

| Dual | −0.040 | −0.040 | 0.036 | 0.036 | −0.041 | −0.042 | −0.149 | −0.148 |

| (−0.183) | (−0.180) | (0.832) | (0.825) | (−0.170) | (−0.175) | (−0.581) | (−0.576) | |

| Indep | 3.707 *** | 3.679 *** | 1.803 *** | 1.792 *** | 3.184 ** | 3.103 ** | 4.275 *** | 4.202 *** |

| (2.641) | (2.617) | (6.339) | (6.269) | (2.270) | (2.211) | (2.671) | (2.616) | |

| Constant | −23.819 *** | −23.970 *** | −1.624 ** | −1.738 ** | −20.872 *** | −21.752 *** | −18.848 *** | −19.434 *** |

| (−4.978) | (−5.001) | (−2.126) | (−2.267) | (−3.967) | (−4.118) | (−3.129) | (−3.220) | |

| N | 10,289 | 10,289 | 10,287 | 10,287 | 8828 | 8828 | 8590 | 8590 |

| Year and Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Adj_R2 | 0.690 | 0.690 | 0.053 | 0.053 | 0.673 | 0.672 | 0.688 | 0.688 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | ESG | ESG | ESG | ESG | ESG | |

| State*Cov1 | −0.039 ** | |||||

| (−2.315) | ||||||

| State*Cov2 | −0.014 ** | |||||

| (−2.257) | ||||||

| SA*Cov1 | 0.057 ** | |||||

| (2.000) | ||||||

| SA*Cov2 | 0.022 ** | |||||

| (2.123) | ||||||

| Opaque*Cov1 | 0.021 ** | |||||

| (2.099) | ||||||

| Opaque*Cov2 | 0.008 ** | |||||

| (2.032) | ||||||

| SA | −9.896 *** | −9.815 *** | ||||

| (−4.192) | (−4.140) | |||||

| Opaque | −0.131 | −0.096 | ||||

| (−0.863) | (−0.667) | |||||

| (5.488) | (−1.515) | (3.293) | ||||

| Cov2 | 0.025 *** | −0.066 * | 0.012 *** | |||

| (5.499) | (−1.658) | (2.723) | ||||

| Size | 1.171 *** | 1.215 *** | 0.603 *** | 0.643 *** | 1.211 *** | 1.266 *** |

| (5.383) | (5.584) | (2.915) | (3.130) | (5.131) | (5.353) | |

| Lev | −2.580 *** | −2.640 *** | −2.366 *** | −2.414 *** | −2.895 *** | −2.937 *** |

| (−3.486) | (−3.564) | (−3.298) | (−3.364) | (−3.549) | (−3.600) | |

| Inst | 0.317 | 0.409 | 0.265 | 0.335 | 0.987 | 1.105 * |

| (0.669) | (0.867) | (0.570) | (0.719) | (1.560) | (1.741) | |

| ROA | 1.976 | 2.161 * | 2.259 * | 2.403 * | 1.794 | 2.087 |

| (1.527) | (1.683) | (1.783) | (1.904) | (1.368) | (1.605) | |

| Growth | −0.055 | −0.073 | −0.011 | −0.030 | −0.063 | −0.079 |

| (−0.428) | (−0.570) | (−0.086) | (−0.233) | (−0.486) | (−0.603) | |

| State | 0.330 | 0.277 | −0.013 | 0.006 | −0.100 | −0.095 |

| (0.742) | (0.635) | (−0.031) | (0.015) | (−0.228) | (−0.218) | |

| Age | 1.832 *** | 1.818 *** | 2.184 *** | 2.171 *** | 2.030 *** | 2.019 *** |

| (48.932) | (49.303) | (25.996) | (25.863) | (51.006) | (51.151) | |

| Big1 | 1.649 | 1.606 | 1.954 | 1.919 | 0.600 | 0.516 |

| (1.333) | (1.294) | (1.596) | (1.567) | (0.435) | (0.372) | |

| Dual | −0.055 | −0.057 | −0.004 | −0.006 | −0.166 | −0.167 |

| (−0.249) | (−0.260) | (−0.016) | (−0.025) | (−0.717) | (−0.725) | |

| Indep | 3.557 ** | 3.488 ** | 3.317 ** | 3.278 ** | 3.488 ** | 3.426 ** |

| (2.543) | (2.488) | (2.423) | (2.389) | (2.421) | (2.366) | |

| Constant | −24.030 *** | −24.651 *** | 22.163 ** | 21.263 ** | −29.861 *** | −30.852 *** |

| (−5.117) | (−5.236) | (2.409) | (2.312) | (−5.865) | (−6.039) | |

| N | 10,289 | 10,289 | 10,289 | 10,289 | 8595 | 8595 |

| Year and Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Adj_R2 | 0.691 | 0.691 | 0.696 | 0.696 | 0.677 | 0.676 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Media | ESG | Media | ESG | Visit | ESG | Visit | ESG | |

| Cov1 | 0.010 *** | 0.052 *** | 0.012 *** | 0.050 *** | ||||

| (4.504) | (5.378) | (10.536) | (5.115) | |||||

| Cov2 | 0.004 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.004 *** | 0.018 *** | ||||

| (3.937) | (5.223) | (9.126) | (4.980) | |||||

| Media | 0.029 * | 0.031 * | ||||||

| (1.864) | (1.917) | |||||||

| Visit | 0.162 * | 0.181 * | ||||||

| (1.948) | (1.724) | |||||||

| Size | 0.057 | 1.177 *** | 0.066* | 1.219 *** | 0.044 ** | 1.172 *** | 0.057 ** | 1.211 *** |

| (1.486) | (5.331) | (1.734) | (5.517) | (1.979) | (5.314) | (2.548) | (5.482) | |

| Lev | 0.481 *** | −2.646 *** | 0.470 *** | −2.706 *** | 0.018 | −2.573 *** | 0.006 | −2.628 *** |

| (2.887) | (−3.576) | (2.822) | (−3.655) | (0.195) | (−3.464) | (0.060) | (−3.537) | |

| Inst | −0.048 | 0.446 | −0.033 | 0.513 | 0.233 *** | 0.389 | 0.256 *** | 0.449 |

| (−0.415) | (0.941) | (−0.288) | (1.081) | (3.607) | (0.820) | (3.971) | (0.944) | |

| ROA | 0.869 *** | 2.158 * | 0.915 *** | 2.342 * | 0.913 *** | 1.965 | 0.995 *** | 2.123 |

| (2.619) | (1.660) | (2.716) | (1.809) | (5.077) | (1.510) | (5.484) | (1.637) | |

| Growth | 0.018 | −0.031 | 0.014 | −0.049 | 0.024 | −0.065 | 0.021 | −0.082 |

| (0.495) | (−0.239) | (0.396) | (−0.383) | (1.402) | (−0.499) | (1.181) | (−0.634) | |

| State | 0.023 | 0.074 | 0.026 | 0.089 | −0.109 | 0.009 | −0.108 | 0.025 |

| (0.225) | (0.173) | (0.249) | (0.210) | (−1.507) | (0.021) | (−1.468) | (0.060) | |

| Age | −0.102 *** | 1.844 *** | −0.105 *** | 1.829 *** | 0.025 *** | 1.831 *** | 0.021 *** | 1.816 *** |

| (−12.575) | (48.277) | (−13.192) | (48.542) | (6.613) | (49.002) | (5.578) | (49.371) | |

| Big1 | −0.203 | 1.873 | −0.212 | 1.838 | 0.202 | 1.683 | 0.187 | 1.645 |

| (−0.859) | (1.504) | (−0.897) | (1.473) | (1.605) | (1.357) | (1.481) | (1.323) | |

| Dual | 0.065 | −0.092 | 0.065 | −0.094 | 0.026 | −0.064 | 0.026 | −0.066 |

| (1.329) | (−0.415) | (1.319) | (−0.422) | (1.090) | (−0.290) | (1.070) | (−0.300) | |

| Indep | 0.665 | 3.590 ** | 0.653 | 3.525 ** | −0.138 | 3.621 ** | −0.153 | 3.560 ** |

| (1.538) | (2.537) | (1.511) | (2.483) | (−0.830) | (2.578) | (−0.920) | (2.526) | |

| Constant | 2.696 *** | −24.329 *** | 2.567 *** | −24.918 *** | −1.139 ** | −23.988 *** | −1.331 *** | −24.516 *** |

| (3.219) | (−5.101) | (3.077) | (−5.213) | (−2.301) | (−5.025) | (−2.678) | (−5.121) | |

| N | 10,197 | 10,197 | 10,197 | 10,197 | 10,272 | 10,272 | 10,272 | 10,272 |

| Year and Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Adj_R2 | 0.060 | 0.691 | 0.060 | 0.691 | 0.094 | 0.691 | 0.089 | 0.690 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, C.; Wu, X. Analyst Coverage and Corporate ESG Performance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12763. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712763

Zhang C, Wu X. Analyst Coverage and Corporate ESG Performance. Sustainability. 2023; 15(17):12763. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712763

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Chunying, and Xiaohui Wu. 2023. "Analyst Coverage and Corporate ESG Performance" Sustainability 15, no. 17: 12763. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712763

APA StyleZhang, C., & Wu, X. (2023). Analyst Coverage and Corporate ESG Performance. Sustainability, 15(17), 12763. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712763