The Factors Influencing 21st Century Skills and Problem-Solving Skills: The Acceptance of Blackboard as Sustainable Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

Problem Statement

2. Research Model and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Information Sharing

2.2. Resource Availability

2.3. Subjective Norm

2.4. Virtual Social Skills

2.5. Communication Skills

2.6. Critical Thinking

2.7. Students’ Self-Efficacy

2.8. Problem-Solving Skills

2.9. Blackboard System Used

2.10. Students’ Academic Performance

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Measurement Instruments and Data Collection

4. Result and Data Analysis

4.1. Measurement Model Analysis

4.2. Measurement Model Assessment Measures Model for Validity and Reliability

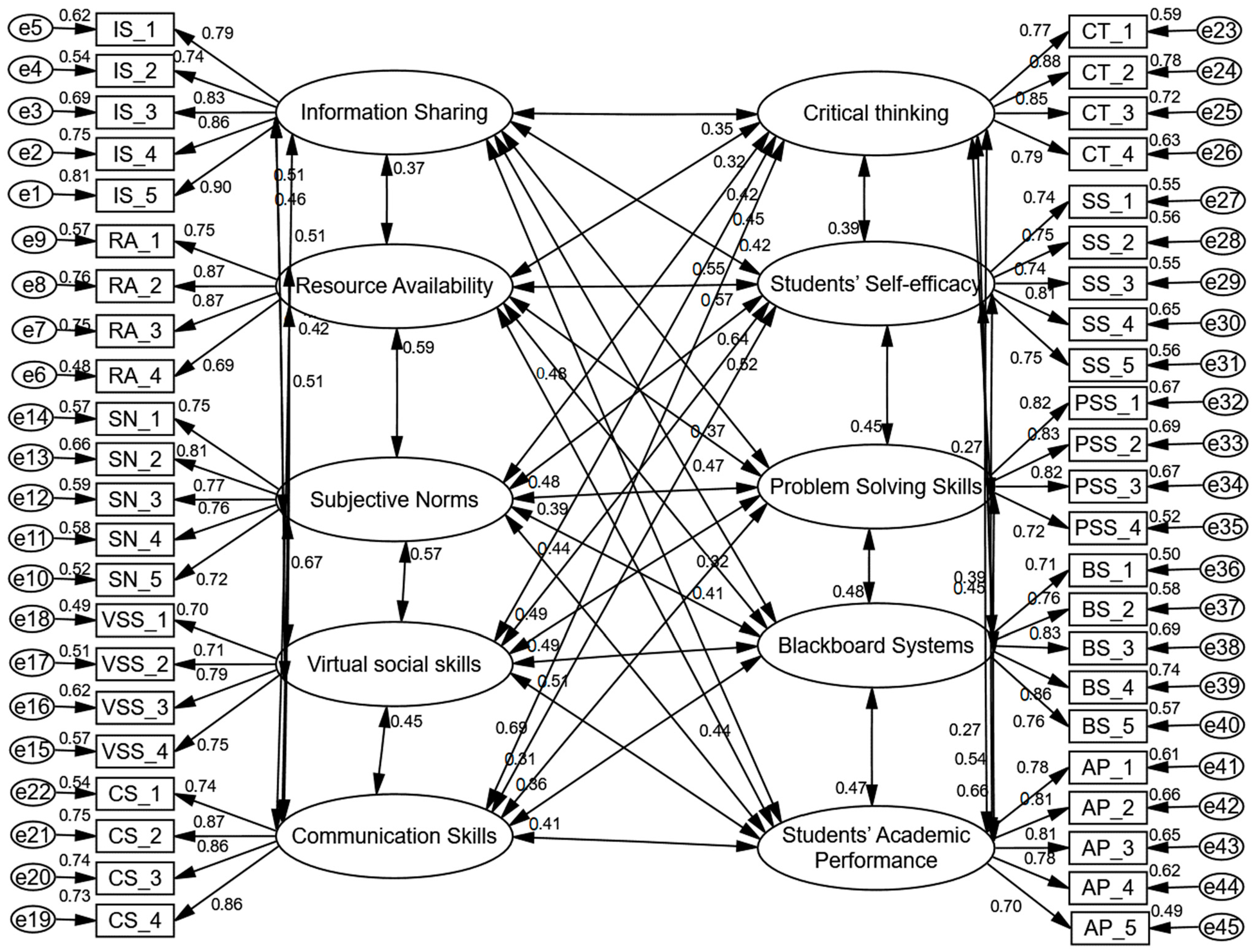

4.3. Structural Equation Model Analysis

4.4. Hypotheses’ Testing Results

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Implications for Theory and Practice

5.2. Limitations

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mohammadi, M.K.; Mohibbi, A.A.; Hedayati, M.H. Investigating the challenges and factors influencing the use of the Blackboard System during the COVID-19 pandemic in Afghanistan. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 5165–5198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.A.; Onwuka, C.I.; Abullais, S.S.; Alqahtani, N.M.; Kota, M.Z.; Atta, A.S.; Shah, S.J.; Ibrahim, M.; Asif, S.M.; Elagib, M.F.A. Perception of Synchronized Online Teaching Using Blackboard Collaborate among Undergraduate Dental Students in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rahmi, A.M.; Shamsuddin, A.; Wahab, E.; Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Alyoussef, I.Y.; Crawford, J. Social media use in higher education: Building a structural equation model for student satisfaction and performance. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1003007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, H.J.; Hativa, N. History, theory and research concerning integrated learning systems. Int. J. Educ. Res. 1994, 21, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.H. Sustainable Education through E-Learning: The Case Study of Ilearn2.0. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhode, J.; Richter, S.; Gowen, P.; Miller, T.; Wills, C. Understanding faculty use of the Blackboard System. Online Learn. J. 2017, 21, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujalli, A.; Khan, T.; Almgrashi, A. University Accounting Students and Faculty Members Using the Blackboard Platform during COVID-19; Proposed Modification of the UTAUT Model and an Empirical Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almekhlafy, S.S.A. Online learning of English language courses via blackboard at Saudi universities in the era of COVID-19: Perception and use. PSU Res. Rev. 2020, 5, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, S. The Effects of Blended Learning on EFL Students’ Vocabulary Enhancement. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 199, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T. A study on satisfaction of users towards Blackboard System at International University—Vietnam National University HCMC. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2021, 26, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, A.M.; Shamsuddin, A.; Alturki, U.; Aldraiweesh, A.; Yusof, F.M.; Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Aljeraiwi, A.A. The influence of information system success and technology acceptance model on social media factors in education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakha, A.H. The impact of Blackboard Collaborate breakout groups on the cognitive achievement of physical education teaching styles during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Grange, L.L.L. Sustainability and Higher Education: From Arborescent to Rhizomatic Thinking. Educ. Philos. Theory 2011, 43, 742–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadneh, N.N.; Atawneh, S.; Khan, W.A.; Almejalli, K.A.; Alhomoud, A. Using Artificial Intelligence to Predict Students’ Academic Performance in Blended Learning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulla, M.A.; Al-Rahmi, W.M. Integrated social cognitive theory with learning input factors: The effects of problem-solving skills and critical thinking skills on learning performance sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Riyath, M.I.; Muhammed Rijah, U.L. Adoption of a Blackboard System among educators of advanced technological institutes in Sri Lanka. Asian Assoc. Open. Univ. J. 2022, 17, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljafen, B. The new educational paradigm in the COVID-19 era: Can Blackboard replace physical teaching in EFL writing classrooms? F1000Research 2022, 11, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almogren, A.S. Art education lecturers’ intention to continue using the blackboard during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: An empirical investigation into the UTAUT and TAM model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 944335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, J. Determining the factors that affect the uses of Mobile Cloud Learning (MCL) platform Blackboard—A modification of the UTAUT model. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, A.M.; Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Alturki, U.; Aldraiweesh, A.; Almutairy, S.; Al-Adwan, A.S. Acceptance of mobile technologies and M-learning by university students: An empirical investigation in higher education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 7805–7826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moawad, R.A. Online Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Academic Stress in University Students. Rev. Rom. Educ. Multidimens. 2020, 12, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Sayed Abdellatif, M. Academic Buoyancy as A Predicator of the Prince Sattam Bin Abdul-Aziz University Students’ Attitudes Towards Using the Blackboard System in E-Learning. Multicult. Educ. 2021, 6, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godber, K.A.; Atkins, D.R. COVID-19 Impacts on Teaching and Learning: A Collaborative Autoethnography by Two Higher Education Lecturers. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 647524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugasundaram, S.; Chidamabaram, D.P. Learners’ Perceptions of the Design Principles of Blackboard. Afr. Educ. Rev. 2020, 17, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, T.; Bird, D.; Farmer, R. Using Blackboard Collaborate, a Digital Web Conference Tool, to Support Nursing Students Placement Learning: A Pilot Study Exploring Its Impact. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019, 38, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, T.T.; Mahomed, A.S.B.; Rahman, A.A.; Hassan, M. Understanding Antecedents of Blackboard System Usage among University Lecturers Using an Integrated TAM-TOE Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, S. Online Learning: A Panacea in the Time of COVID-19 Crisis. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2020, 49, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, T.T.F. The Performance of Online Teaching for Flipped Classroom Based on COVID-19 Aspect. Asian J. Educ. Soc. Stud. 2020, 8, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageeh, A.I. EFL Students’ Readiness for e-Learning: Factors Influencing e-Learners’ Acceptance of the Blackboard in a Saudi University. JALT Call J. 2011, 7, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affouneh, S.; Salha, S.N.; Khlaif, Z. Designing Quality E-Learning Environments for Emergency Remote Teaching in Coronavirus Crisis. Interdiscip. J. Virtual Learn. Med. Sci. 2020, 11, 135–137. [Google Scholar]

- Zarei, S.; Mohammadi, S. Challenges of Higher Education Related to E-Learning in Developing Countries during COVID-19 Spread: A Review of the Perspectives of Students, Instructors, Policymakers, and ICT Experts. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 85562–85568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favale, T.; Soro, F.; Trevisan, M.; Drago, I.; Mellia, M. Campus Traffic and E-Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic. Comput. Netw. 2020, 176, 107290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.A.; Qazi, Z.; Qazi, W.; Ahmed, M. E-Learning in Higher Education during COVID-19: Evidence from Blackboard Learning System. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2022, 14, 1603–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, H.; Yuen, A. Factors Affecting Students’ and Teachers’ Use of BS—Towards a Holistic Framework; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (LNCS) Series (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7411, pp. 306–316. [Google Scholar]

- Alsamiri, Y.A.; Alsawalem, I.M.; Hussain, M.A.; Al Blaihi, A.A.; Aljehany, M.S. Providing accessible distance learning for students with disabilities in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2022, 9, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustun, A.B.; Karaoglan Yilmaz, F.G.; Yilmaz, R. Investigating the role of accepting Blackboard System on students’ engagement and sense of community in blended learning. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 4751–4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousbahi, F.; Alrazgan, M.S. Investigating IT faculty resistance to Blackboard System adoption using latent variables in an acceptance technology model. Sci. World J. 2015, 2015, 375651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Doll, W.; Deng, X.; Williams, M. The impact of organisational support, technical support, and self-efficacy on faculty perceived benefits of using Blackboard System. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2018, 37, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, H.; Rada, R. Understanding the influence of perceived usability and technology self-efficacy on teachers’ technology acceptance. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2011, 43, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Mishra, S. E-Learning in a Mega Open University: Faculty attitude, barriers and motivators. EMI Educ. Media Int. 2007, 44, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, S.A.; Katan, H.; Hidayat-ur-Rehman, I. Instructors’ behavioural intention to use Blackboard System: An integrated TAM perspective. TEM J. 2018, 7, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlhaka, H. Blackboard collaborated-based instruction in an academic writing class: Sociocultural perspectives of learning. Electron. J. e-Learn. 2020, 18, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, A.; Zareravasan, A.; Rabiee Savoji, S.; Amani, M. Exploring factors influencing students’ continuance intention to use the Blackboard System (BS): A multi-perspective framework. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2022, 30, 1475–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhadreti, O. Assessing Academics’ Perceptions of Blackboard Usability Using SUS and CSUQ: A Case Study during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2021, 37, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrycza, S.; Kuciapski, M. Determinants of academic E-learning systems acceptance. In Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 333, pp. 68–85. [Google Scholar]

- Uğur, N.G.; Turan, A.H. E-learning adoption of academicians: A proposal for an extended model. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2018, 37, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkarani, A.S.; Thobaity, A.A.L. Medical staff members’ experiences with blackboard at TAIF University, Saudi Arabia. J. Multidiscip. Healthcare 2020, 13, 1629–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bervell, B.; Umar, I.N. Validation of the UTAUT model: Re-considering non-linear relationships of exogeneous variables in higher education technology acceptance research. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2017, 13, 6471–6490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyam, N. Factors impacting special education teachers’ acceptance and actual use of technology. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2019, 24, 2035–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon Arulraj, D. A Critical Understanding of Blackboard System. Internet J. Epidemiol. 2013, 2, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, B.J.; Ramírez, J.M.O.; Rodríguez-Reséndiz, J.; Dector, A.; García, R.G.; González-Durán, J.E.E.; Sánchez, F.F. Blackboard System-based evaluation to determine academic efficiency performance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Nam, M.W.; Cha, S.B. University students’ behavioral intention to use mobile learning: Evaluating the technology acceptance model. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2012, 43, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongsri, N.; Shen, L.; Bao, Y. Investigating academic major differences in perception of computer self-efficacy and intention toward e-learning adoption in China. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2020, 57, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, F.; Ward, R.; Ahmed, E. Investigating the influence of the most commonly used external variables of TAM on students’ Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) and Perceived Usefulness (PU) of e-portfolios. Comput. Human. Behav. 2016, 63, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rughoobur-Seetah, S.; Hosanoo, Z.A. An evaluation of the impact of confinement on the quality of e-learning in higher education institutions. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2021, 29, 422–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailizar, M.; Burg, D.; Maulina, S. Examining university students’ behavioural intention to use e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: An extended TAM model. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 7057–7077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mulhem, A. Investigating the effects of quality factors and organizational factors on university students’ satisfaction of e-learning system quality. Cogent Educ. 2020, 7, 1787004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasinghe, A.; Hamid, J.A.; Khatibi, A.; Azam, S.M.M.F. The adequacy of UTAUT-3 in interpreting academician’s adoption to e-Learning in higher education environments. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 2020, 17, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muliadi, M.; Muhammadiah, M.; Amin, K.F.; Kaharuddin, K.; Junaidi, J.; Pratiwi, B.I.; Fitriani, F. The information sharing among students on social media: The role of social capital and trust. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Chuang, S.S. Social capital and individual motivations on knowledge sharing: Participant involvement as a moderator. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, M.I.M.; Al-Jabri, I.M. Social networking, knowledge sharing, and student learning: The case of university students. Comput. Educ. 2016, 99, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyouzbaky, B.A.; Al-Sabaawi, M.Y.M.; Tawfeeq, A.Z. Factors affecting online knowledge sharing and its effect on academic performance. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, N.; Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Alfarraj, O.; Alzahrani, A.; Yahaya, N.; Al-Rahmi, A.M. Integrated three theories to develop a model of factors affecting students’ academic performance in higher education. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 98725–98742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, G.; Heidari, E.; Mehrvarz, M.; Safavi, A.A. Impact of online social capital on academic performance: Exploring the mediating role of online knowledge sharing. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 6599–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T. Followership: An Important Social Resource for Organizational Resilience. In The Resilience Framework: Organizing for Sustained Viability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Ojo, A.O.; Fawehinmi, O.; Yusliza, M.Y. Examining the predictors of resilience and work engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogus, T.J.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Organizational resilience: Towards a theory and research agenda. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–10 October 2007; pp. 3418–3422. [Google Scholar]

- Gittell, J.H.; Cameron, K.; Lim, S.; Rivas, V. Relationships, Layoffs, and organizational resilience: Airline industry responses to september 11. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2006, 42, 300–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldiab, A.; Chowdhury, H.; Kootsookos, A.; Alam, F. Prospect of eLearning in Higher Education Sectors of Saudi Arabia: A Review. Energy Procedia 2017, 110, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren Little, J. Locating learning in teachers’ communities of practice: Opening up problems of analysis in records of everyday work. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2002, 18, 917–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintalapati, N.; Daruri, V.S.K. Examining the use of YouTube as a Learning Resource in higher education: Scale development and validation of TAM model. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology acceptance model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. Decis. Sci. 2008, 39, 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigdem, H.; Topcu, A. Predictors of instructors’ behavioral intention to use Blackboard System: A Turkish vocational college example. Comput. Human. Behav. 2015, 52, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.Y.-C.; Jong, M.S.-Y.; Lau, W.W.-F.; Meng, Y.L.; Chai, C.S.; Chen, M. Validating the General Extended Technology Acceptance Model for E-Learning: Evidence From an Online English as a Foreign Language Course Amid COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.A.; Beidel, D.C.; Murray, M.J. Social skills interventions for children with Asperger’s syndrome or high-functioning autism: A review and recommendations. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2008, 38, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salavera, C.; Usán, P.; Jarie, L. Emotional intelligence and social skills on self-efficacy in Secondary Education students. Are there gender differences? J. Adolesc. 2017, 60, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendo-Lázaro, S.; León-del-Barco, B.; Felipe-Castaño, E.; Polo-del-Río, M.I.; Iglesias-Gallego, D. Cooperative team learning and the development of social skills in higher education: The variables involved. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Kelley, T.; Knowles, J.G. Factors Influencing Student STEM Learning: Self-Efficacy and Outcome Expectancy, 21st Century Skills, and Career Awareness. J. STEM Educ. Res. 2021, 4, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosain, M.S.; Mustafi, M.A.A.; Parvin, T. Factors affecting the employability of private university graduates: An exploratory study on Bangladeshi employers. PSU Res. Rev. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirdağ, S. Communication Skills and Time Management as the Predictors of Student Motivation. Int. J. Psychol. Educ. Stud. 2021, 8, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrández-Antón, T.; Ferreira-Padilla, G.; Del-Pino-Casado, R.; Ferrández-Antón, P.; Baleriola-Júlvez, J.; Martínez-Riera, J.R. Communication skills training in undergraduate nursing programs in Spain. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 42, 102653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succi, C.; Canovi, M. Soft skills to enhance graduate employability: Comparing students and employers’ perceptions. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 1834–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadiyanto, H.; Failasofah, F.; Armiwati, A.; Abrar, M.; Thabran, Y. Students’ practices of 21st century skills between conventional learning and blended learning. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2021, 18, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, J. Team-Based Learning in professional writing courses for accounting graduates: Positive impacts on student engagement, accountability and satisfaction. Account. Educ. 2021, 30, 234–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.; Shah, N.S.; Mali, D.; Arquero, J.L.; Joyce, J.; Hassall, T. The use and measurement of communication self-efficacy techniques in a UK undergraduate accounting course. Account. Educ. 2022, 2022, 2113108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.H.; Morris, M.L.; Yoon, S.W. Combined effect of instructional and learner variables on course outcomes within an online learning environment. J. Interact. Online Learn. 2006, 5, 255–269. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, C.S.; Deng, F.; Tsai, P.S.; Koh, J.H.L.; Tsai, C.C. Assessing multidimensional students’ perceptions of twenty-first-century learning practices. Asia Pacific Educ. Rev. 2015, 16, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facione, P.A. Critical Thinking: What It Is and Why It Counts. Insight Assess. 2011, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bezanilla, M.J.; Fernández-Nogueira, D.; Poblete, M.; Galindo-Domínguez, H. Methodologies for teaching-learning critical thinking in higher education: The teacher’s view. Think. Ski. Creat. 2019, 33, 100584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellaera, L.; Weinstein-Jones, Y.; Ilie, S.; Baker, S.T. Critical thinking in practice: The priorities and practices of instructors teaching in higher education. Think. Ski. Creat. 2021, 41, 100856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, K.J.; Kebritchi, M.; Leary, H.M.; Halverson, D.M. Enhancing Critical Thinking Skills through Decision-Based Learning. Innov. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 711–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayçiçek, B. Integration of critical thinking into curriculum: Perspectives of prospective teachers. Think. Ski. Creat. 2021, 41, 100895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, J.P.; Arnal-Pastor, M.; Pagán-Castaño, E.; Guijarro-García, M. Bibliometric analysis of the literature on critical thinking: An increasingly important competence for higher education students. Econ. Res. Istraz. 2022, 36, 2125888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Freeman, W.H.; Lightsey, R. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. J. Cogn. Psychother. 1999, 13, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, T. An Investigation on the Role of Perceived Ease of Use, Perceived Use and Self Efficacy in Determining Continuous Usage Intention Towards an E-Learning System. J. Distance Educ. e-Learn. 2019, 7, 268–276. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Maroof, R.S.; Alhumaid, K.; Salloum, S. The continuous intention to use e-learning, from two different perspectives. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, D.D.; Mazanov, J.; Meacheam, D.; Heaslip, G.; Hanson, J. Attitude, digital literacy and self efficacy: Flow-on effects for online learning behavior. Internet High. Educ. 2016, 29, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalişkan, S.; Selçuk, G.S.; Erol, M. Instruction of problem solving strategies: Effects on physics achievement and self-efficacy beliefs. J. Balt. Sci. Educ. 2010, 9, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C. Computational thinking—What it might mean and what we might do about it. In Proceedings of the 16th Annual Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science (ITiCSE’11), Darmstadt, Germany, 27–29 June 2011; pp. 223–227. [Google Scholar]

- Kocak, O.; Coban, M.; Aydin, A.; Cakmak, N. The mediating role of critical thinking and cooperativity in the 21st century skills of higher education students. Think. Ski. Creat. 2021, 42, 100967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, D.; Heri Santoso, R. Device Learning Development Using Cabri 3D with Problem-Solving Method Based on Oriented Critical Thinking Ability and Learning Achievements of Junior High School Students. In Proceedings of the 5th Asia Pasific Education Conference (AECON 2018), Purwokerto, Indonesia, 13–14 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Giannakopoulos, P.; Buckley, S. Do problem solving, critical thinking and creativity play a role in knowledge management? A theoretical mathematics perspective. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Knowledge Management (ECKM 2009), Vicenza, Italy, 3–4 September 2009; pp. 327–337. [Google Scholar]

- Aein, F.; Hosseini, R.S.; Naseh, L.; Safdari, F.; Banaian, S. The effect of problem-solving-based interprofessional learning on critical thinking and satisfaction with learning of nursing and midwifery students. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 9, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirhan, E.; Şahin, F. The Effects of Different Kinds of Hands-on Modeling Activities on the Academic Achievement, Problem-Solving Skills, and Scientific Creativity of Prospective Science Teachers. Res. Sci. Educ. 2021, 51, 1015–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwanto; Saputro, A.D.; Rohaeti, E.; Prodjosantoso, A.K. Promoting critical thinking and Problem Solving Skills of Preservice Elementary Teachers through Process-Oriented Guided-Inquiry Learning (POGIL). Int. J. Instr. 2018, 11, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnleitner, P.; Keller, U.; Martin, R.; Brunner, M. Students’ complex problem-solving abilities: Their structure and relations to reasoning ability and educational success. Intelligence 2013, 41, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Roy, R.; Seetharaman, P. Course management system adoption and usage: A process theoretic perspective. Comput. Human Behav. 2013, 29, 2535–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alturki, U.T.; Aldraiweesh, A.; Kinshuck, D. Evaluating the Usability And Accessibility Of BS “Blackboard” At King Saud University. Contemp. Issues Educ. Res. 2016, 9, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGeorge, E.L.; Homan, S.R.; Dunning, J.B.; Elmore, D.; Bodie, G.D.; Evans, E.; Khichadia, S.; Lichti, S.M. The influence of learning characteristics on evaluation of audience response technology. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2008, 19, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basri, W.S.; Alandejani, J.A.; Almadani, F.M. ICT Adoption Impact on Students’ Academic Performance: Evidence from Saudi Universities. Educ. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1240197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcı, Ü.; Ergün, E. Online students’ BS activities and their effect on engagement, information literacy and academic performance. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2022, 30, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhassna, H.; Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Yahya, N.; Zakaria, M.A.Z.M.; Kosnin, A.B.M.; Darwish, M. Development of a new model on utilizing online learning platforms to improve students’ academic achievements and satisfaction. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2020, 17, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alismaiel, O.A.; Cifuentes-Faura, J.; Al-Rahmi, W.M. Online Learning, Mobile Learning, and Social Media Technologies: An Empirical Study on Constructivism Theory during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, A.M.; Shamsuddin, A.; Wahab, E.; Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Alturki, U.; Aldraiweesh, A.; Almutairy, S. Integrating the Role of UTAUT and TTF Model to Evaluate Social Media Use for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 905968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maatouk, Q.; Othman, M.S.; Aldraiweesh, A.; Alturki, U.; Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Aljeraiwi, A.A. Task-technology fit and technology acceptance model application to structure and evaluate the adoption of social media in academia. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 78427–78440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga Sánchez, R.; Cortijo, V.; Javed, U. Students’ perceptions of Facebook for academic purposes. Comput. Educ. 2014, 70, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A.; Stahl, B.; Prior, M. Developing an instrument for e-public services’ acceptance using confirmatory factor analysis: Middle east context. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2012, 24, 18–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, C.; Abraham, J. Modeling educational usage of social media in pre-service teacher education. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2019, 31, 21–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Othman, M.S.; Yusuf, L.M. Using social media for research: The role of interactivity, collaborative learning, and engagement on the performance of students in Malaysian post-secondary institutes. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hosen, M.; Ogbeibu, S.; Giridharan, B.; Cham, T.H.; Lim, W.M.; Paul, J. Individual motivation and social media influence on student knowledge sharing and learning performance: Evidence from an emerging economy. Comput. Educ. 2021, 172, 104262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okongo, R.B.; Ngao, G.; Rop, N.K.; Nyongesa, W.J. Effect of Availability of Teaching and Learning Resources on the Implementation of Inclusive Education in Pre-School Centers in Nyamira North Sub-County, Nyamira County, Kenya. J. Educ. Pract. 2015, 6, 132–141. [Google Scholar]

- Van Acker, F.; van Buuren, H.; Kreijns, K.; Vermeulen, M. Why teachers use digital learning materials: The role of self-efficacy, subjective norm and attitude. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2013, 18, 495–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, I.; Yousaf, A.; Walia, S.; Bashir, M. What Shapes E-Learning Effectiveness among Tourism Education Students? An Empirical Assessment during COVID19. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2022, 30, 100337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Haggerty, N. Why people benefit from e-learning differently: The effects of psychological processes on e-learning outcomes. Inf. Manag. 2008, 45, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafi, Y.; Murtadho, N.; Hassan, A.R.; Ikhsan, M.A.; Diyana, T.N. Development and validation of a questionnaire for teacher effective communication in Qur’an learning. Br. J. Relig. Educ. 2020, 42, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limna, P.; Siripipatthanakul, S.; Phayaprom, B.; Siripipattanakul, S. The Relationship between Twenty-First-Century Learning Model (4Cs), Student Satisfaction and Student Performance-Effectiveness. Int. J. Behav. Anal. 2022, 2, 4011953. [Google Scholar]

- Towip, T.; Widiastuti, I.; Budiyanto, C.W. Students’ Perceptions and Experiences of Online Cooperative Problem-Based Learning: Developing 21st Century Skills. Int. J. Pedagog. Teach. Educ. 2022, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezer, B.; Yilmaz, R. Blackboard System acceptance scale (BSAS): A validity and reliability study. Australas J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 35, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, H.A.; Ali, E.M.; Belbase, S. Graduate students’ experience and academic achievements with online learning during COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabah, N.M.; Altalbe, A.A. Learning Outcomes of Educational Usage of Social Media: The Moderating Roles of Task–Technology Fit and Perceived Risk. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaya, N.; Abu Khait, R.; Madani, R.; Khattak, M.N. Organizational Resilience of Higher Education Institutions: An Empirical Study during COVID-19 Pandemic. High. Educ. Policy 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizimana, B.; Orodtho, J.A. Teaching and Learning Resource Availability and Teachers’ Effective Classroom Management and Content Delivery in Secondary Schools in Huye District, Rwanda. J. Educ. Pract. 2014, 5, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Conley, Q.; Earnshaw, Y.; McWatters, G. Examining Course Layouts in Blackboard: Using Eye-Tracking to Evaluate Usability in a Blackboard System. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2020, 36, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanzer, D.; Postlewaite, E.; Zargarpour, N. Relationships Among Noncognitive Factors and Academic Performance: Testing the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research Model. AERA Open 2019, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montroy, J.J.; Bowles, R.P.; Skibbe, L.E.; Foster, T.D. Social skills and problem behaviors as mediators of the relationship between behavioral self-regulation and academic achievement. Early Child. Res. Q. 2014, 29, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buabeng-Andoh, C.; Baah, C. Pre-service teachers’ intention to use Blackboard System: An integration of UTAUT and TAM. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 2020, 17, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.M.; Chen, P.C.; Law, K.M.Y.; Wu, C.H.; Lau, Y.-Y.; Guan, J.; He, D.; Ho, G.T.S. Comparative analysis of Student’s live online learning readiness during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in the higher education sector. Comput. Educ. 2021, 168, 104211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moeti, B.; Killion Mgawi, R.; Smitta Moalosi, W.T. Critical Thinking among Post-Graduate Diploma in Education Students in Higher Education: Reality or Fuss? J. Educ. Learn. 2016, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calaguas, N.P.; Consunji, P.M.P. A structural equation model predicting adults’ online learning self-efficacy. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 6233–6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.C.; Tsai, Y.T. The Effect of University Students’ Emotional Intelligence, Learning Motivation and Self-Efficacy on Their Academic Achievement—Online English Courses. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 818929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.-H.; Ahn, E.; Hwang, J.-M. Effects of Critical Thinking and Communication Skills on the Problem-Solving Ability of Dental Hygiene Students. J. Dent. Hyg. Sci. 2019, 19, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, A.A.; Rajeh, M.T. Blackboard in Dental Education: Educators’ Perspectives During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2022, 13, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic | Description | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 129 | 32.6 |

| Male | 267 | 67.4 | |

| Age | 18–20 | 51 | 12.8 |

| 21–24 | 67 | 16.8 | |

| 25–29 | 129 | 32.5 | |

| 30–34 | 95 | 23.8 | |

| 35 and above | 54 | 13.5 | |

| Specialization | Humanities Colleges | 200 | 50.0 |

| Scientific Colleges | 120 | 30.0 | |

| Medical Colleges | 76 | 20.0 |

| Factors | Items | Load | CA | CR | AVE | GCR | GI | CA | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information sharing | IS_1 | 0.789 | 0.914 | 0.914 | 0.682 | Critical thinking | CT_1 | 0.771 | 0.893 | 0.894 | 0.680 |

| IS_2 | 0.737 | CT_2 | 0.882 | ||||||||

| IS_3 | 0.831 | CT_3 | 0.849 | ||||||||

| IS_4 | 0.865 | CT_4 | 0.792 | ||||||||

| IS_5 | 0.898 | ||||||||||

| Resource availability | RA_1 | 0.753 | 0.871 | 0.875 | 0.640 | Students’ Self-efficacy | SS_1 | 0.741 | 0.870 | 0.870 | 0.573 |

| RA_2 | 0.872 | SS_2 | 0.747 | ||||||||

| RA_3 | 0.867 | SS_3 | 0.740 | ||||||||

| RA_4 | 0.692 | SS_4 | 0.807 | ||||||||

| SS_5 | 0.749 | ||||||||||

| Subjective norm | SN_1 | 0.753 | 0.874 | 0.875 | 0.584 | Problem-solving Skills | PSS_1 | 0.821 | 0.875 | 0.876 | 0.640 |

| SN_2 | 0.814 | PSS_2 | 0.833 | ||||||||

| SN_3 | 0.771 | PSS_3 | 0.820 | ||||||||

| SN_4 | 0.759 | PSS_4 | 0.720 | ||||||||

| SN_5 | 0.721 | ||||||||||

| Virtual social skills | VSS_1 | 0.699 | 0.825 | 0.828 | 0.546 | Blackboard System | BS_1 | 0.706 | 0.887 | 0.889 | 0.616 |

| VSS_2 | 0.714 | BS_2 | 0.761 | ||||||||

| VSS_3 | 0.786 | BS_3 | 0.830 | ||||||||

| VSS_4 | 0.753 | BS_4 | 0.859 | ||||||||

| BS_5 | 0.758 | ||||||||||

| Communication Skills | CS_1 | 0.736 | 0.897 | 0.899 | 0.692 | Academic performance | AP_1 | 0.779 | 0.883 | 0.884 | 0.606 |

| CS_2 | 0.867 | AP_2 | 0.814 | ||||||||

| CS_3 | 0.861 | AP_3 | 0.807 | ||||||||

| CS_4 | 0.856 | AP_4 | 0.785 | ||||||||

| AP_5 | 0.701 |

| Model | χ2/df | CFI | IFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | ≤5.0 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≤0.09 | ≤0.08 |

| Model 1 (Final model) | 2.233 | 0.908 | 0.909 | 0.901 | 0.039 | 0.051 |

| VSS | SN | RA | CS | CT | IS | SS | PSS | BS | AP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VSS | 0.737 | |||||||||

| SN | 0.355 | 0.736 | ||||||||

| RA | 0.311 | 0.434 | 0.876 | |||||||

| CS | 0.315 | 0.498 | 0.424 | 0.900 | ||||||

| CT | 0.319 | 0.313 | 0.280 | 0.350 | 0.901 | |||||

| IS | 0.339 | 0.376 | 0.324 | 0.423 | 0.300 | 0.918 | ||||

| SS | 0.316 | 0.402 | 0.414 | 0.490 | 0.287 | 0.394 | 0.702 | |||

| PSS | 0.324 | 0.329 | 0.359 | 0.242 | 0.213 | 0.302 | 0.297 | 0.791 | ||

| BS | 0.318 | 0.266 | 0.319 | 0.271 | 0.299 | 0.264 | 0.289 | 0.348 | 0.763 | |

| AP | 0.326 | 0.294 | 0.354 | 0.305 | 0.213 | 0.351 | 0.340 | 0.452 | 0.332 | 0.733 |

| H | Factors | Relationships | Factors | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p-Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Information sharing | --------> | Students’ Self-efficacy | 0.201 | 0.038 | 5.270 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H2 | Information sharing | --------> | Problem-solving Skills | 0.103 | 0.048 | 2.167 | 0.030 | Accepted |

| H3 | Resource availability | --------> | Students’ Self-efficacy | 0.233 | 0.041 | 5.731 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H4 | Resource availability | --------> | Problem-solving Skills | 0.202 | 0.051 | 3.987 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H5 | Subjective norm | --------> | Students’ Self-efficacy | 0.249 | 0.048 | 5.200 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H6 | Subjective norm | --------> | Problem-solving Skills | 0.182 | 0.062 | 2.920 | 0.004 | Accepted |

| H7 | Virtual social skills | --------> | Students’ Self-efficacy | 0.117 | 0.043 | 2.694 | 0.007 | Accepted |

| H8 | Virtual social skills | --------> | Problem-solving Skills | 0.213 | 0.053 | 4.012 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H9 | Communication Skills | --------> | Problem-solving Skills | 0.123 | 0.056 | 2.199 | 0.028 | Accepted |

| H10 | Critical thinking | --------> | Problem-solving Skills | 0.008 | 0.045 | 0.168 | 0.867 | Rejected |

| H11 | Students’ Self-efficacy | --------> | Problem-solving Skills | 0.130 | 0.063 | 2.049 | 0.040 | Accepted |

| H12 | Students’ Self-efficacy | --------> | Blackboard System | 0.269 | 0.049 | 5.442 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H13 | Problem-solving Skill | --------> | Blackboard System | 0.339 | 0.046 | 7.300 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H14 | Blackboard System | --------> | Academic performance | 0.435 | 0.044 | 9.836 | 0.000 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alturki, U.; Aldraiweesh, A. The Factors Influencing 21st Century Skills and Problem-Solving Skills: The Acceptance of Blackboard as Sustainable Education. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12845. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712845

Alturki U, Aldraiweesh A. The Factors Influencing 21st Century Skills and Problem-Solving Skills: The Acceptance of Blackboard as Sustainable Education. Sustainability. 2023; 15(17):12845. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712845

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlturki, Uthman, and Ahmed Aldraiweesh. 2023. "The Factors Influencing 21st Century Skills and Problem-Solving Skills: The Acceptance of Blackboard as Sustainable Education" Sustainability 15, no. 17: 12845. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712845

APA StyleAlturki, U., & Aldraiweesh, A. (2023). The Factors Influencing 21st Century Skills and Problem-Solving Skills: The Acceptance of Blackboard as Sustainable Education. Sustainability, 15(17), 12845. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712845