COVID-19 Perceived Risk, Travel Risk Perceptions and Hotel Staying Intention: Hotel Hygiene and Safety Practices as a Moderator

Abstract

:1. Introduction

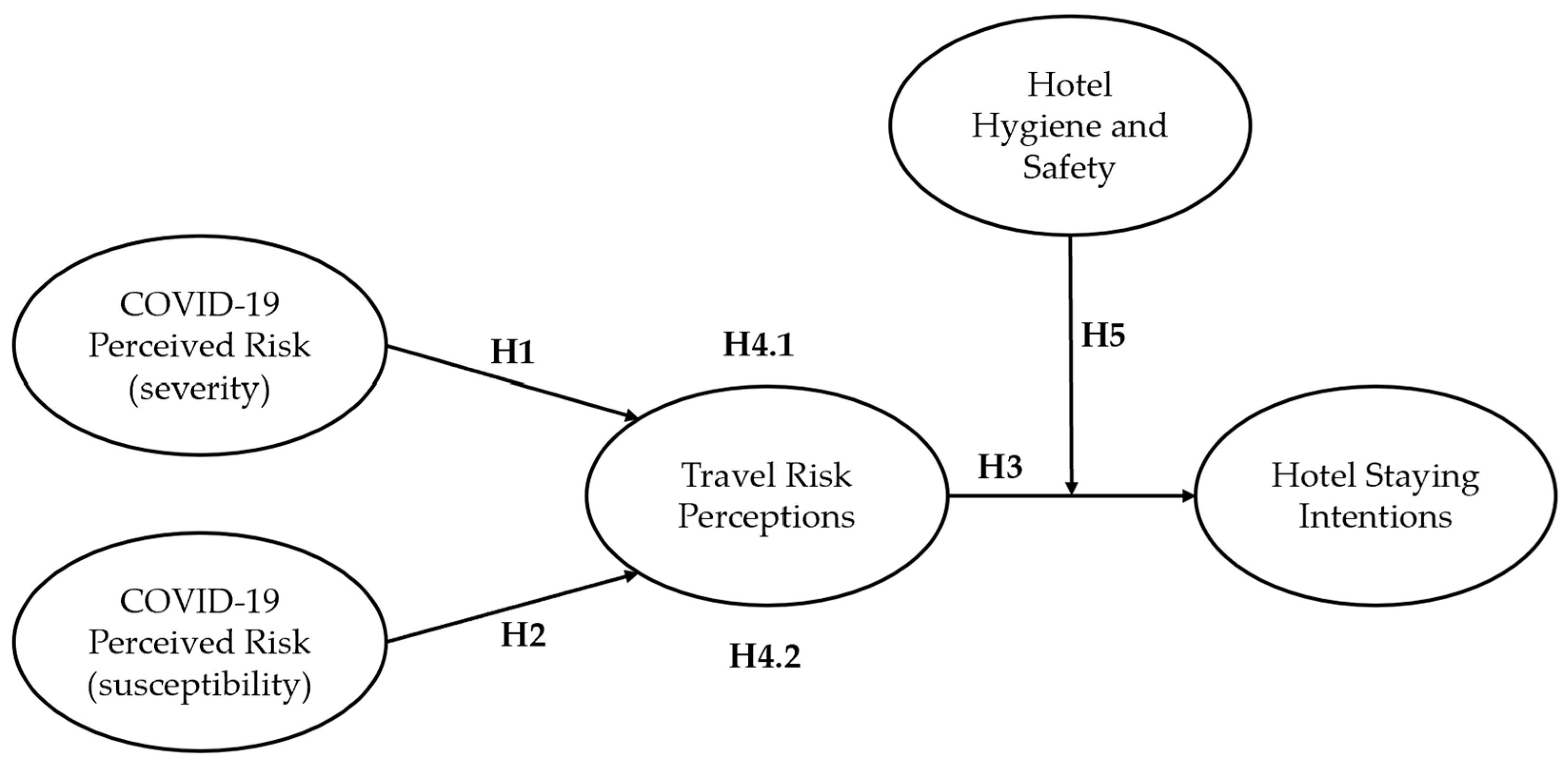

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

2.1. Perceived Risk of COVID-19 and Travel Risk Perceptions

2.2. Travel Risk Perceptions and Hotel Staying Intention

2.3. Mediating Effects of Travel Risk Perceptions

2.4. Moderating Effects of Hotel Hygiene and Safety Practices

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Participants

3.2. Survey Instrument and Measures

3.3. Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. CFA Results, Validity, and Reliability of Measurements

4.2. Results of Hypotheses

4.3. Moderating Effect of Hypothesis 5

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hadi, D.M.; Naeem, M.A.; Karim, S. Impact of COVID-19 on the connectedness across global hospitality stocks. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 104, 103243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Lu, J.; Qiu, M.; Xiao, X. Changes in travel behaviors and intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic and recovery period: A case study of China. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2022; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism Bureau, Ministry of Transportation and Communications. The Entry and Exit Statistics. Available online: https://admin.taiwan.net.tw/fapi/AttFile?type=AttFile&id=24758 (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Apaolaza, V.; Paredes, M.R.; Hartmann, P.; García-merino, J.D.; Marcos, A. The effect of threat and fear of COVID-19 on booking intentions of full board hotels: The roles of perceived coping efficacy and present-hedonism orientation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 105, 103255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Luo, Q.; Ritchie, B.W. Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Malik, M.; Sarwat, N. Consequences of job insecurity for hospitality workers amid COVID-19 pandemic: Does social support help? J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2021, 30, 957–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Moreno, A.; Garcia-Morales, V.J.; Martin-Rojas, R. Going beyond the curve: Strategic measures to recover hotel activity in times of COVID-19. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 96, 102928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddux, J.E.; Rogers, R.W. Protection motivation and self-efficacy: A revised theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 19, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J. Psychol. Interdiscip. Appl. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, J.J.; Almanza, B.A.; Behnke, C.; Nelson, D.C.; Neal, J. Norovirus on cruise ships: Motivation for handwashing? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu-Lastres, B.; Ritchie, B.W.; Mills, D.J. Travellers’ self-protections against health risks: An application of the full Protection Motivation Theory. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 78, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.Y.; Yeh, C. Tourist hesitation in destination decision making. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Khan, A.; Bibi, S.; Zhao, W.; Chen, W.; Lee, Y. The effects of COVID-19 risk perception on travel intention: Evidence from Chinese travelers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 655860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, S.G.; Haldorai, K.; Seo, W.S.; Kim, W.G. COVID-19 and hospitality 5.0: Redefining hospitality operations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Isa, S.M.; Ramayah, T. Does uncertainty avoidance moderate the effect of self-congruity on revisit intention? A two-city (Auckland and Glasgow) investigation. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 24, 100703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golets, A.; Farias, J.; Pilati, R.; Helena, C. COVID-19 pandemic and tourism: The impact of health risk perception and intolerance of uncertainty on travel intentions. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.W.; Park, J.; Lee, J.H.; Park, H. Recovering from the COVID-19 shock: The role of risk perception and perceived effectiveness of protective measures on travel intention during the pandemic. Serv. Bus. 2022, 16, 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.K.; Gazi, M.A.I.; Bhuiyan, M.A.; Rahaman, M.A. Effect of Covid-19 pandemic on tourist travel risk and management perceptions. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.; Ding, C.; Lee, H. Post-SARS tourist arrival recovery patterns: An analysis based on a catastrophe theory. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Huang, S. Chinese tourists visiting volatile destinations: Integrating cultural values into motivation-based segmentation. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 15, 520–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AHLA, Leisure and Hospitality Industry Proves Hardest Hit by COVID-19. Available online: https://www.ahla.com/covid-19s-impact-hotel-industry (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Floyd, D.L.; Prentice-Dunn, S.; Rogers, R.W. A meta-analysis of research on protection motivation theory. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Jarumaneerat, T.; Promsivapallop, P.; Kim, M. What influences restaurant dining out and diners’ self-protective intention during the COVID-19 pandemic: Applying the Protection Motivation Theory. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 109, 103400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pine, R.; McKercher, B. The impact of SARS on Hong Kong’s tourism industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2004, 16, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, A.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Kaplanidou, K.; Zhan, F. Destination risk perceptions among US residents for London as the host city of the 2012 Summer Olympic Games. Tour. Manag. 2013, 38, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavas, U. Correlates of vacation travel: Some impirical evidence. J. Serv. Mark. 1990, 5, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuburger, L.; Egger, R. Travel risk perception and travel behavior during the Covid-19 pandemic 2020: A case study of the DACH region. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Kim, W.H.; Kim, S.B. How does COVID-19 differ from previous crises? A comparative study of health-related crisis research in the tourism and hospitality context. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 103, 103199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, N.T.; Fazekas, K.I. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: A theory-informed, systematic review. Prev. Med. 2007, 45, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, N.T.; Chapman, G.B.; Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M.; McCaul, K.D.; Weinstein, N.D. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: The example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007, 26, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazione, S.; Perrault, E.; Pace, K. Impact of information exposure on perceived risk, efficacy, and preventative behaviors at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P. Stealth risks and catastrophic risks: On risk perception and crisis recovery strategies. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 2008, 23, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, L.; Moen, B.E.; Rundmo, T. Explaining risk perception: An evaluation of the psychometric paradigm in risk perception research. Rotunde Publ. Rotunde 2004, 84, 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, N.D. The precaution adoption process. Health Psychol. 1988, 7, 355–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boholm, A. Comparative studies of risk perception: A review of twenty years of research. J. Risk Res. 1998, 1, 135–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti, A.; Vigolo, V.; Yfantidou, G.; Gutuleac, R. Customer experience management strategies in upscale restaurants: Lessons from the Covid-19 pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 109, 103416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M.; Pizam, A.; Bahja, F. Antecedents and outcomes of health risk perceptions in tourism, following the COVID-19 pandemic. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Atadil, H.A. Do you dare to travel to China? An examination of China’s destination image amid the COVID-19. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 40, 100881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; Baláž, V. Tourism, risk tolerance and competences: Travel organization and tourism hazards. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longwoods International. COVID-19 Travel Sentiment Study-Wave 5. 2020. Available online: https://longwoods-intl.com/news-press-release/covid-19-travel-sentiment-study-wave-5 (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Tsaur, S.H.; Tzeng, G.H.; Wang, K.C. Evaluating tourist risks from fuzzy perspectives. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 796–812. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, Y.; Jang, S.S. The Effect of COVID-19 on hotel booking intentions: Investigating the roles of message appeal type and brand loyalty. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 108, 103357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.; Ekinci, Y.; Ramkissoon, H.; Thorpe, A. Evolving effects of COVID-19 safety precaution expectations, risk avoidance, and socio-demographics factors on customer hesitation toward patronizing restaurants and hotels. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2022, 31, 396–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice-Dunn, S.; Rogers, R.W. Protection motivation theory and preventive health: Beyond the health belief model. Health Educ. Res. 1986, 1, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyanto, I.; Wiblishauser, M.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Schroeder, A. The dynamics of travel avoidance: The case of Ebola in the US. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leggat, P.A.; Brown, L.H.; Aitken, P.; Speare, R. Level of concern and precaution taking among Australians regarding travel during pandemic (H1N1) 2009: Results from the 2009 Queensland Social Survey. J. Travel. Med. 2010, 17, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, M.; Ivanov, I.K.; Ivanov, S. Travel behaviour after the pandemic: The case of Bulgaria. Anatolia 2020, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.W.; Crotts, J.C.; Hefner, F.L. Cross-cultural tourist behaviour: A replication and extension involving Hofstede’s uncertainty avoidance dimension. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 6, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.S.; Crotts, J. Relationships between Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and tourist satisfaction: A cross-country cross-sample examination. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.M.; Kellaris, J.J. Cross-national differences in proneness to scarcity effects: The moderating roles of familiarity, uncertainty avoidance, and need for cognitive closure. Psychol. Mark. 2004, 21, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Law, R.; Wei, J. Effect of cultural distance on tourism: A study of pleasure visitors in Hong Kong. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 19, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Kim, K.; Jang, J. Uncertainty avoidance as a moderator for influences on foreign resident dining out behaviors. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 900–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srite, M.; Karahanna, E.; Evaristo, J.R. Levels of culture and individual behaviour: An integrative perspective. Inf. Manag. 2006, 5, 30–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, F.; Xiao, Q.; Chon, K. COVID-19 and China’s hotel industry: Impacts, a disaster management framework, and post-pandemic agenda. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Wen, J. Effects of COVID-19 on hotel marketing and management: A perspective article. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2563–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Seo, J.; Hyun, S.S. Perceived hygiene attributes in the hotel industry: Customer retention amid the COVID-19 crisis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I. Factors of satisfaction and intention to use peer-to-peer accommodation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehseen, S.; Ramayah, T.; Sajilan, S. Testing and controlling for common method variance: A review of available methods. Manag. Sci. 2017, 4, 142–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson: London, UK; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Pearson: London, UK; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 28, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Hoffman, J.M.; West, S.G.; Sheets, V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falahuddin, A.F.; Tergu, C.T.; Brollo, R.; Nanda, R.O. Post COVID-19 Pandemic international travel: Does risk perception and stress-level affect future travel intention? J. Ilmu Sosial. Ilmu Politik. 2020, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X. Coronavirus pandemic and tourism: Dynamic stochastic general equilibrium modeling of infectious disease outbreak. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De La Hoz-Correa, A.; Muñoz-Leiva, F. The role of information sources and image on the intention to visit a medical tourism destination: A cross-cultural analysis. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, I.E.; Elkhwesky, Z.; Ramkissoon, H. A content analysis for government’s and hotels’ response to COVID-19 pandemic in Egypt. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022, 22, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.C.; Ng, A. Responding to crisis: Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and hotels in Singapore. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 6, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.K.; Mark, C.K.; Yeung, M.P.; Chan, E.; Graham, C. The role of the hotel industry in the response to emerging epidemics: A case study of SARS in 2003 and H1N1 swine flu in 2009 in Hong Kong. Glob. Health 2018, 14, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, R.S.G.; Stedefeldt, E. COVID-19 pandemic underlines the need to build resilience in commercial restaurants’ food safety. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefer, A.; Pampaka, D.; Wagner, E.R.; Herrera, A.A.; Alonso, E.G.; López-Perea, N.; Portero, R.C.; Herrera-León, L.; Herrera-León, S.; Gallo, D.N. Management of a COVID-19 outbreak in a hotel in Tenerife, Spain. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 96, 384–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosemberg, M.A.S. Health and safety considerations for hotel cleaners during Covid-19. Occup. Med. 2020, 70, 382–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Zhu, G. Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 300–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.; Phi, G. Strategic responses of the hotel sector to COVID-19: Toward a refined pandemic crisis management framework. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 94, 102808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Kozak, M.; Yang, S.; Liu, F. COVID-19: Potential effects on Chinese citizens’ lifestyle and travel. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yan, H.; Casey, T.; Wu, C.H. Creating a safe haven during the crisis: How organizations can achieve deep compliance with COVID-19 safety measures in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.M.; Peng, K.L.; Ren, L.; Lin, C.W. Hospitality co-creation with mobility impaired people. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E.; Elshaer, I.; Hasanein, A.M.; Abdelaziz, A.S. Responses to COVID-19: The role of performance in the relationship between small hospitality enterprises’ resilience and sustainable tourism development. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Frequency | % | Variables | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 7. Location | ||||

| Male | 247 | 49.4 | Northern Taiwan | 227 | 45.4 |

| Female | 253 | 50.6 | Central Taiwan | 122 | 24.4 |

| Southern Taiwan | 136 | 27.2 | |||

| 2. Age | Eastern and Outlying Islands | 15 | 3.0 | ||

| 18–20 | 2 | 0.4 | |||

| 21–30 | 100 | 20.0 | 8. Frequency of staying out | ||

| 31–40 | 92 | 18.4 | 1–2 times | 19 | 3.8 |

| 41–50 | 97 | 19.4 | 3–4 times | 67 | 13.4 |

| 51–60 | 181 | 36.2 | 5–6 times | 143 | 28.6 |

| 61–70 | 22 | 4.4 | 7–8 times | 166 | 33.2 |

| 71–80 | 6 | 1.2 | 9–10 times | 48 | 9.6 |

| 11 times or more | 21 | 4.2 | |||

| 3. Education | |||||

| Under junior high school | 9 | 1.8 | 9. County of residence | ||

| High school | 49 | 9.8 | Taipei City | 76 | 15.2 |

| College or University | 348 | 69.6 | New Taipei City | 105 | 21.0 |

| Above graduate | 94 | 18.8 | Keelung City | 5 | 1.0 |

| Yilan County | 6 | 1.2 | |||

| 4. Marriage | Taoyuan City | 26 | 5.2 | ||

| Unmarried | 218 | 43.6 | Hsinchu City | 5 | 1.0 |

| Married no kid | 41 | 8.2 | Hsinchu County | 4 | 0.8 |

| Married with kids | 225 | 45.0 | Miaoli County | 7 | 1.4 |

| Divorced or widowed | 16 | 3.2 | Taichung City | 80 | 16.0 |

| Nantou County | 4 | 0.8 | |||

| 5. Occupation | Changhua County | 16 | 3.2 | ||

| Student | 19 | 3.8 | Yunlin County | 15 | 3.0 |

| Government agencies | 67 | 13.4 | Chiayi City | 8 | 1.6 |

| Manufacture | 143 | 28.6 | Tainan City | 9 | 1.8 |

| Service | 166 | 33.2 | Kaohsiung City | 39 | 7.8 |

| Freelance | 48 | 9.6 | Pingtung County | 74 | 14.8 |

| Homemaker | 21 | 4.2 | Taitung County | 6 | 1.2 |

| Retired | 11 | 2.2 | Kinmen County | 6 | 1.2 |

| Others | 25 | 5.0 | Lienchiang County | 6 | 1.2 |

| 6. Monthly household income (NTD) | |||||

| $20,000 or less | 57 | 12.5 | |||

| $20,001–$40,000 | 127 | 27.8 | |||

| $40,001–$60,000 | 112 | 24.5 | |||

| $60,001–$80,000 | 67 | 14.7 | |||

| $80,001–$100,000 | 37 | 8.1 | |||

| More than $100,001 | 15 | 3.3 | |||

| Scales and Items | Loadings | t-Value | α | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived risk of COVID-19 (severity) (PCe) | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.81 | |||

| PCe1 | Coronavirus (COVID-19) is a serious risk. | 0.89 | ||||

| PCe2 | Coronavirus (COVID-19) is a serious threat. | 0.94 | 33.11 | |||

| PCe3 | Coronavirus (COVID-19) is harmful. | 0.92 | 31.60 | |||

| PCe4 | Coronavirus (COVID-19) is deadly. | 0.85 | 26.60 | |||

| Perceived risk of COVID-19 (susceptibility) (PCu) | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.85 | |||

| PCu1 | I am at risk for getting with coronavirus (COVID-19) | 0.92 | ||||

| PCu2 | I am susceptible to getting with coronavirus (COVID-19) | 0.94 | 39.06 | |||

| PCu3 | I may possibly get with coronavirus (COVID-19) | 0.94 | 39.13 | |||

| PCu4 | I may be diagnosed with coronavirus (COVID-19) | 0.89 | 32.68 | |||

| Travel risk perceptions (TR) | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.53 | |||

| TR1 | Tourism is mainly responsible for the spread of the coronavirus | 0.50 | ||||

| TR2 | Tourism will be massively affected by coronavirus | 0.65 | 10.18 | |||

| TR3 | Staying in a hotel is a risk, as there are many people from different countries, who could carry the virus | 0.80 | 11.22 | |||

| TR4 | I fear that the virus will be carried by tourists to my near surroundings | 0.80 | 11.26 | |||

| TR5 | Traveling should be prohibited to avoid a wider spread of the virus | 0.78 | 11.142 | |||

| TR6 | Currently, it is irresponsible to be sent on business trips to countries with a high number of cases | 0.73 | 10.77 | |||

| TR7 | Currently, it is irresponsible to travel to destinations with cases of coronavirus | 0.77 | 11.02 | |||

| Hotel hygiene and safety practices (HH) | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.69 | |||

| HH1 | This hotel cleans guest rooms and public areas (i.e., toilets and washroom floors) using disinfectants. | 0.90 | ||||

| HH2 | This hotel washes its laundry using antibacterial products and practices (i.e., towels, bed covers, blankets, and pillows). | 0.83 | 25.68 | |||

| HH3 | This hotel cleans in-room facilities (i.e., desks, chairs, sofas, beds, mirrors, and closets) using disinfectants. | 0.92 | 33.04 | |||

| HH4 | The rooms in this hotel are equipped with special air cleaners to prevent aerosol infections. | 0.79 | 23.43 | |||

| HH5 | This hotel conducts hot water sterilization (heating for more than 30 s in boiling water) of utensils used in its restaurants (i.e., cutlery, crockery, and cutting boards). | 0.85 | 27.41 | |||

| HH6 | This hotel cleans restaurant facilities (i.e., tables and chairs) using disinfectants | 0.91 | 31.55 | |||

| HH7 | This hotel keeps the tables and chairs in restaurants and public areas at a social distance to avoid group gatherings | 0.55 | 13.49 | |||

| Hotel staying intentions (HSI) | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.88 | |||

| HSI1 | I expect to continue using this accommodation in the future. | 0.91 | ||||

| HSI2 | I can see myself using this accommodation in the future | 0.96 | 38.38 | |||

| HSI3 | It is likely that I will use this accommodation in the future. | 0.96 | 38.59 | |||

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived risk of COVID-19 (risk) | 1.70 | 0.78 | (0.81) | ||||

| 2. Perceived risk of COVID-19 (threat) | 3.36 | 1.35 | 0.26 ** | (0.85) | |||

| 3. Travel risk perceptions | 1.96 | 0.76 | 0.63 ** | 0.25 ** | (0.53) | ||

| 4. Hotel hygiene and safety practices | 5.64 | 0.87 | −0.33 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.37 ** | (0.69) | |

| 5. Hotel staying intensions | 5.45 | 0.97 | −0.28 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.24 ** | 0.47 ** | (0.88) |

| Effect | Point Estimation | Significance | Hypotheses Testing Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value | Bootstrapping | PRODCLIN2 | |||||

| Bias-Corrected 95% CI | 95% CI | ||||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||

| Direct effect | |||||||

| PRC (severity)→TRP | 0.68 | 0.001 *** | 0.604 | 0.759 | --- | H1 supported | |

| PRC (susceptibility)→TRP | 0.08 | 0.050 * | 0.000 | 0.165 | --- | H2 supported | |

| TRP→HSI | −0.27 | 0.001 *** | −0.356 | −0.191 | --- | H3 supported | |

| Indirect effect | |||||||

| PC (severity)→TRP→HSI | −0.19 | 0.001 *** | −0.225 | −0.124 | −0.336 | −0.148 | H4-1 supported (partial mediation) |

| PC (susceptibility)→TRP→HSI | −0.02 | 0.041 * | −0.050 | −0.001 | −0.033 | −0.001 | H4-2 supported (partial mediation) |

| Paths | Low HHSP (N = 130) | High HHSP (N = 144) | Unconstrained Model Chi-Square | Constrained Model Chi-Square | ΔX2 (Δdf = 1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Coefficients | Z-Value | Standardized Coefficients | Z-Value | ||||

| H5: Travel risk perceptions → Hotel staying intentions | −0.28 | −2.99 ** | −0.07 | −2.99 ** | 571.080 (df = 116) | 578.078 (df = 115) | 6.998 ** (p = 0.01) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Teng, C.-C.; Cheng, Y.-J.; Yen, W.-S.; Shih, P.-Y. COVID-19 Perceived Risk, Travel Risk Perceptions and Hotel Staying Intention: Hotel Hygiene and Safety Practices as a Moderator. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13048. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713048

Teng C-C, Cheng Y-J, Yen W-S, Shih P-Y. COVID-19 Perceived Risk, Travel Risk Perceptions and Hotel Staying Intention: Hotel Hygiene and Safety Practices as a Moderator. Sustainability. 2023; 15(17):13048. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713048

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeng, Chih-Ching, Ya-Jen Cheng, Wen-Shen Yen, and Ping-Yu Shih. 2023. "COVID-19 Perceived Risk, Travel Risk Perceptions and Hotel Staying Intention: Hotel Hygiene and Safety Practices as a Moderator" Sustainability 15, no. 17: 13048. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713048