Assessment of Impacts and Resilience of Online Food Services in the Post-COVID-19 Era

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (i)

- What are the resilience challenges of OFS involving social, environmental, and economic dimensions?

- (ii)

- What policy interventions are necessary to make online food services resilient?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Advantages of OFS

2.2. Disadvantages of OFS

2.3. Role of OFS in Global Agenda

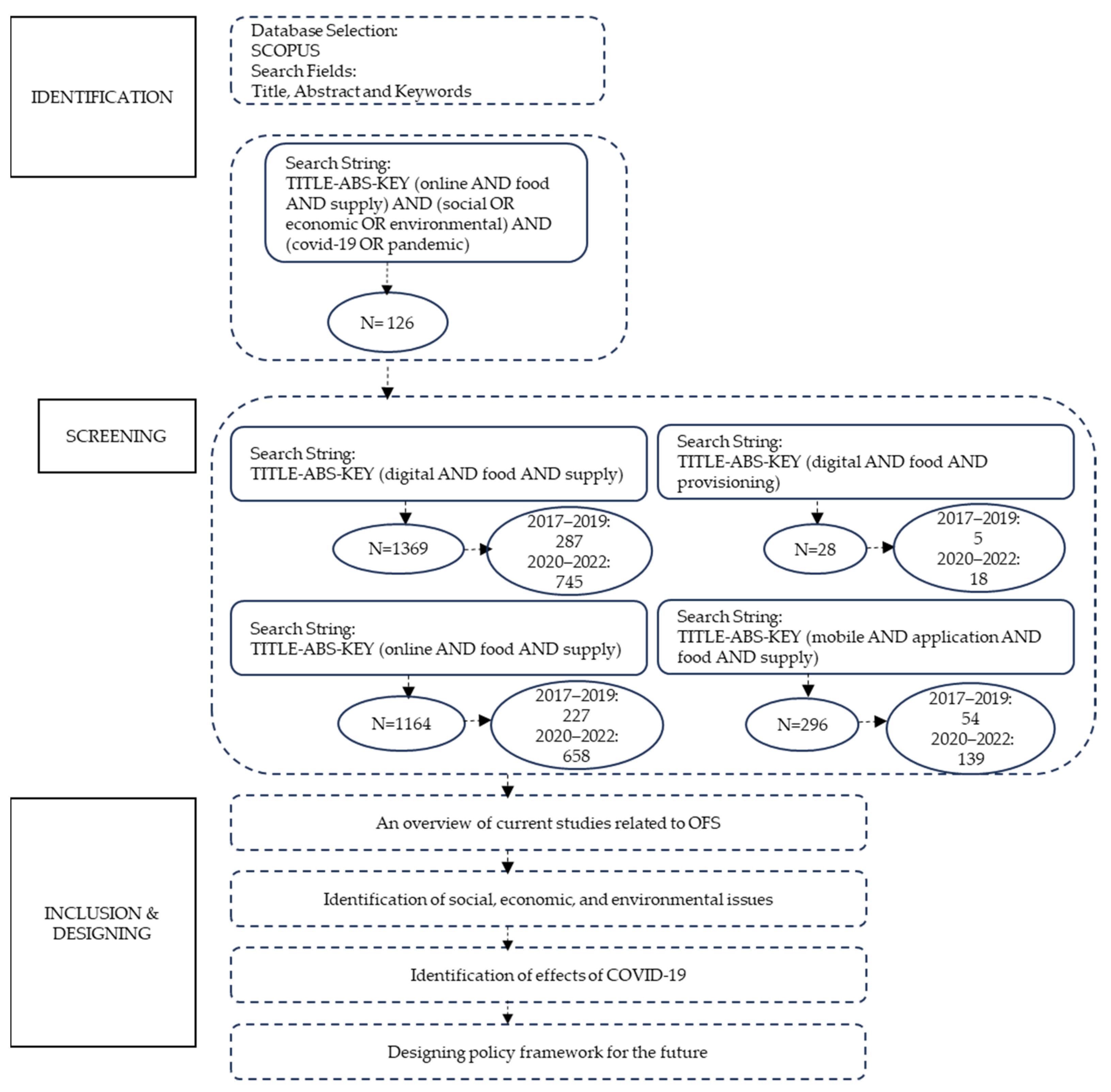

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Social Impacts of OFS

4.2. Environmental Impacts of OFS

4.3. Economic Impacts of OFS

4.4. Online Food Servicing after COVID-19

4.5. Resilience Challenges of OFS

4.6. Policy Framework for the Resilience of OFS

- High dependency on unsustainable plastic packaging is one of the challenges of OFS. National governments can regulate the use of packaging materials for OFS by introducing economic incentives, including subsidies to use alternative and recyclable or reusable packaging materials. National governments can also provide financial support for alternative packaging industries;

- National governments can play a vital role in improving working conditions for employees through regulatory measures such as setting up a minimum wage rate and ensuring coverage for social insurance etc.;

- Advertising junk food online or in the mass media can be regulated on a national level. For example, the UK government enacted a ban in 2023, prohibiting the advertising of junk food online [116].

- Local governments can take action to make neighborhood food ecosystems healthier by developing the necessary infrastructure, such as providing footpaths or cycling paths to access healthier food sources. One example of such local action is the 15-min urban transformation in Paris that advocates access to basic amnesties within 15 min on foot or by bicycle [117];

- Local governments can establish online platforms for all restaurants where OFS providers can upload their menu information, including nutritional labeling and eco-labeling. This scheme is useful for consumers when they wish to order healthier food items. For example, the Yokohama City Government established the Takeout and Delivery Yokohama online platform for restaurants where owners can upload useful information for consumers [118].

- To reduce food waste, OFS providers can give more useful information about the volume of food items, so that consumers can avoid over-purchasing when they order;

- To ensure OFS is resilient, a company should take necessary policy actions to improve working conditions that will improve the work satisfaction of employees. For example, Menu Log Australia has set up a minimum wage to improve workers’ rights [39];

- OFS providers can play a vital role in reducing plastic waste by shifting from single-use plastic packaging to recyclable or reusable packaging items. Several OFS providers, including Cup Club in the UK and Globelet in Australia, have already started replacing single-use items. This action can also create new business opportunities, such as leasing reusable packaging items, as seen in companies like Go Box (USA) and Re-Cup (Germany) [119].

- The resilience of OFS businesses depends on improving the level of customer satisfaction. Therefore, consumer choice can be an important factor in bringing about changes for resilience concerning OFS. Ordering more environment-friendly food choices can contribute to reducing food waste and plastic waste and minimizing the carbon footprint.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roosevelt, M.; Raile, E.D.; Anderson, J.R. Resilience in Food Systems: Concepts and Measurement Options in an Expanding Research Agenda. Agronomy 2023, 13, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookings. The Potential—And pitfalls—Of the Digitalization of America’s Food System. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-potential-and-pitfalls-of-the-digitalization-of-americas-food-system/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Resilient Food System. Resilient Food Systems Is Committed to Fostering Sustainability and Resilience for Food Security in Sub-Saharan Africa. Available online: https://www.resilientfoodsystems.co/about (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Hirth, S.; Bürstmayr, T.; Strüver, A. Discourses of sustainability and imperial modes of food provision: Agri-food-businesses and consumers in Germany. Agric. Hum. Values 2022, 39, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, M.A.; Raine, K.D. Digital Food Retail: Public Health Opportunities. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Revenues of the Online Food Delivery Market Worldwide from 2017 to 2027, by Segment. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1170631/online-food-delivery-market-size-worldwide/ (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- McKinsey and Company. The State of Grocery Retail 2022: Europe. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/state-of-grocery-europe (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Statista. Size of the Online Food Delivery Market across India from 2016 to 2020, with an Estimate for 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/744350/online-food-delivery-market-size-india/ (accessed on 4 February 2023).

- IMF Blog. Pandemic’s E-Commerce Surge Proves Less Persistent, More Varied. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/03/17/pandemics-e-commerce-surge-proves-less-persistent-more-varied (accessed on 4 February 2023).

- National Bureau of Economic Research. E-Commerce during Covid: Stylized Facts from 47 Economies. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w29729 (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Heidenstrøm, N.; Hebrok, M. Towards realizing the sustainability potential within digital food provisioning platforms: The case of meal box schemes and online grocery shopping in Norway. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 831–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, N. SNAP at the community scale: How neighborhood characteristics affect participation and food access. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, 1646–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Gobbo, A.; Forno, F.; Magnani, N. Making “good food” more practicable? The reconfiguration of alternative food provisioning in the online world. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 862–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granheim, S.I.; Lovhaug, A.L.; Terragni, L.; Torheim, L.E.; Thurston, M. Mapping the digital food environment: A systematic scoping review. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13356. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, N. Roles of Cities in Creating Healthful Food Systems. Annu. Rev. Public. Health 2021, 43, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melis, K.; Campo, K.; Breugelmans, E.; Lamey, L. The Impact of the Multi-channel Retail Mix on Online Store Choice: Does Online Experience Matter? J. Retail. 2015, 91, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trude, A.C.B.; Lowery, C.M.; Ali, S.H.; Vedovato, G.M. An equity-oriented systematic review of online grocery shopping among low-income populations: Implications for policy and research. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 1294–1310. [Google Scholar]

- Moragues-Faus, A. Distributive food systems to build just and livable futures. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 583–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čajić, S.; Brückner, M.; Brettin, S. A recipe for localization? Digital and analogue elements in food provisioning in Berlin A critical examination of potentials and challenges from a gender perspective. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 820–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkman, K.L.; Rogers, T.; Bazerman, M.H. I’ll have the ice cream soon and the vegetables later: A study of online grocery purchases and order lead time. Mark. Lett. 2009, 21, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatz, L.Y.; Moran, A.J.; Franckle, R.L.; Block, J.P.; Hou, T.; Blue, D. Comparing Online and In-Store Grocery Purchases. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookings. Delivering to Deserts: New Data Reveals the Geography of Digital Access to Food in the US. Brookings Institution. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/essay/delivering-to-deserts-new-data-reveals-the-geography-of-digital-access-to-food-in-the-us/ (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Gustafson, A.; Gillespie, R.; DeWitt, E.; Cox, B.; Dunaway, B.; Haynes-Maslow, L. Online Pilot Grocery Intervention among Rural and Urban Residents Aimed to Improve Purchasing Habits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosior, K. Economic, Ethical and Legal Aspects of Digitalization in the Agri-Food Sector. Zagadnienia Ekon. Rolnej/Probl. Agric. Econ. 2020, 2, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattersley, L.; Dixon, J. Supermarkets, food systems and public health: Facing the challenges. In Food Security, Nutrition and Sustainability, 1st ed.; Lawrence, G., Lyons, K., Wallington, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, O. Sharing food and risk in Berlin’s urban food commons. Geoforum 2019, 99, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, J.C.; Garzon, W.; Brooker, P.; Sakarkar, G.; Carranzaa, S.A.; Yunado, L.; Rincon, A. Evaluation of collaborative consumption of food delivery services through web mining techniques. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 46, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prügl, E. Transforming Masculine Rule: Agriculture and Rural Development in the European Union; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Som Castellano, R.L. Alternative food networks and food provisioning as a gendered act. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Vernez-Moudon, A.; Reis, R.; Turrell, G.; Dannenberg, A.L.; Badland, H.; Foster, S.; Lowe, M.; Sallis, J.F.; Stevenson, M.; et al. City planning and population health: A global challenge. Lancet 2016, 388, 2912–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: United Nations. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 27 August 2023).

- Dang, A.K.; Tran, B.X.; Nguyen, C.T.; Le, H.T.; Do, H.T.; Nguyen, H.D.; Nguyen, L.H.; Nguyen, T.H.; Mai, H.T.; Tran, T.D.; et al. Consumer preference and attitude regarding online food products in Hanoi, Vietnam. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhong, T.; Crush, J. Boon or Bane? Urban Food Security and Online Food Purchasing during the COVID-19 Epidemic in Nanjing, China. Land 2022, 11, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, S.R.; Gibson, A.A.; Roy, R.; Malloy, J.A.; Raeside, R.; Jia, S.S.; Singleton, A.C.; Mandoh, M.; Todd, A.R.; Wang, T.; et al. Junk food on demand: A cross-sectional analysis of the nutritional quality of popular online food delivery outlets in Australia and New Zealand. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchise Buyer. The 10 Biggest Fast Food Franchises in the Australian Market. 2020. Available online: https://www.franchisebuyer.com.au/articles/the-10-biggest-fast-food-franchises-in-the-australian-market (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Wooliscroft, B.; Ganglmair-Wooliscroft, A. Growth, excess and opportunities: Marketing systems’ contributions to society. J Macromarket. 2018, 38, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprint Law. The Gig Economy And Australian Law: What’s Next? 2021. Available online: https://sprintlaw.com.au/gig-economy-in-australia/ (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Jia, S.S.; Gibson, A.A.; Ding, D.; Allman-Farinelli, M.; Phongsavan, P.; Redfern, J.; Partridge, S.R. Perspective: Are Online Food Delivery Services Emerging as Another Obstacle to Achieving the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals? Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 858475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.K.; Galgani, F.; Thompson, R.C.; Barlaz, M. Accumulation and fragmentation of plastic debris in global environments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 1985–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Larson, N.I.; Fulkerson, J.A.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Story, M. Family meals and adolescents: What have we learned from Project EAT (Eating Among Teens)? Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnettler, B.; Rojas, J.; Grunert, K.G.; Lobos, G.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Lapo, M.; Hueche, C. Family and food variables that influence life satisfaction of mother-father-adolescent triads in a South American country. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 40, 3747–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meah, A.; Jackson, P. Convenience as care: Culinary antinomies in practice. Environ. Plan. A 2017, 49, 2065–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, J. Consuming takeaway food: Convenience, waste and Chinese young people’s urban lifestyle. J. Consum. Cult. 2021, 21, 848–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimaiti, M.; Zhao, X.; Jia, M.; Ru, Y.; Zhu, S. How we eat determines what we become: Opportunities and challenges brought by food delivery industry in a changing world in China. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 1282–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimaiti, M.; Ma, X.; Zhao, X.; Jia, M.; Li, J.; Yang, M.; Ru, Y.; Yang, F.; Wang, N.; Zhu, S. Multiplicity and complexity of food environment in China: Full-scale field census of food outlets in a typical district. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FHA Food and Bevarage. Takeaway.com Monopoly Could Derail Food Delivery Growth in Germany. Available online: https://www.foodnhotelasia.com/takeaway-com-monopoly-could-derail-food-delivery-growth-in-germany/ (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Abdulkader, R.S.; Jeyashree, K.; Kumar, V.; Kannan, K.S.; Venugopal, D. Online Food Delivery System in India: Profile of Restaurants and Nutritional Value of Food Items. Vis. J. Bus. Perspect. 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Casey, T.W. Who uses a mobile phone while driving for food delivery? The role of personality, risk perception, and driving self-efficacy. J. Saf. Res. 2020, 73, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safira, M.; Chikaraishi, M. The impact of online food delivery service on eating-out behavior: A case of Multi-Service Transport Platforms (MSTPs) in Indonesia. Transportation 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medium. What Is the Real Impact of Food Deliveries? Available online: https://medium.com/collectivfood/what-is-the-impact-of-food-deliveries-bf7c867b9f13 (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- British International Investment. How Does an Online Supermarket in India Impact Farmers? Available online: https://www.bii.co.uk/en/news-insight/insight/articles/how-does-an-online-supermarket-in-india-impact-farmers/ (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Paredes, A. The political work of food delivery: Consumer co- operative systems and women’s labor in “relationless” Japan. Food Cult. Soc. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Gupta, N. An Analysis of Online Food Home Delivery and Its Impact on Restaurants in India. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348880563_An_Analysis_of_Online_Food_Home_Delivery_and_its_impact_on_restaurants_in_India (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Ilyuk, V. Like throwing a piece of me away: How online and in-store grocery purchase channels affect consumers’ food waste. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lad, M.; Brahmbhatt, J. Sustainable takeaway food packaging: To minimize environmental problems of online food delivery. Int. J. Creat. Res. Thoughts 2022, 10, 662–666. [Google Scholar]

- Catalyze. Doing More with Less: A Survey on Take-Back Systems for Food Delivery in Indonesia. Available online: https://catalyzecommunications.com/c-notes/2021/06/doing-more-with-less-a-survey-on-takeback-systems-for-food-delivery-in-indonesia (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Song, G.; Zhang, H.; Duan, H.; Xu, M. Packaging waste from food delivery in China’s mega cities. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 130, 226–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkei. Japan Goes back to Plastic Use as COVID Fuels Food Deliveries. Available online: https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Materials/Japan-goes-back-to-plastic-use-as-COVID-fuels-food-deliveries (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Sustainable Review. The Truth about the Environmental Impact of Takeout Food. Available online: https://sustainablereview.com/environmental-impact-of-takeout-food/?utm_content=anc-true&utm_content=vc-true (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Eco-Business. Reducing the Carbon Footprint of Online Retail. Available online: https://www.eco-business.com/news/reducing-the-carbon-footprint-of-online-retail/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- RSIS. Plastic Pollution in Southeast Asia: Wasted Opportunity? Available online: https://www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/nts/plastic-pollution-in-southeast-asia-wasted-opportunity/#.ZEum53ZByiM (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Wen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, D. The environmental impact assessment of a takeaway food delivery order based on of industry chain evaluation in China. China Environ. Sci. 2019, 39, 4017–4024. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.; Klemes, J.J.; Varbanov, P.S.; Alwi, S.R.W. Energy-emission-waste nexus of food deliveries in China. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2018, 70, 661–666. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, B.; Song, W. Online catering takeout development, urban environmental negative externalities and waste regulation. J. Shaanxi Norm. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 47, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Z.; Meng, B.; Lin, Y.; Chen, S. Research on the status quo of sorting and disposing of food waste from takeout of college students. Mod. Food 2019, 5, 187–191. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.-E.; Liu, G.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhou, B.; Gao, S.; Cheng, S. The weight of unfinished plate: A survey-based characterization of restaurant food waste in Chinese cities. Waste Manag. 2017, 66, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.; Choe Ja, Y. Exploring perceived risk in building successful drone food delivery services. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3249–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, H. Consequences of a green image of drone food delivery services: The moderating role of gender and age. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 872–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Mirosa, M.; Bremer, P. Review of online food delivery platforms and their impacts on sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; Dhir, A.; Talwar, S.; Islam, N.; Sharma, P. Balancing food waste and sustainability goals in online food delivery: Towards a comprehensive conceptual framework. Technovation 2022, 117, 102606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Newyork Times. Here Is Who’s behind the Global Surge in Single Use Plastic. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/18/climate/single-use-plastic.html (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Food Navigator. Safety vs. Sustainability: Single-Use Food Packaging Use Rises Due to COVID-19—But Is It Truly Safer? Available online: https://archive.is/416ZL#selection-1947.0-1947.102 (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Janairo, J.I.B. Unsustainable plastic consumption associated with online food delivery services in the new normal. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2021, 2, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdict Food Service. Online Food Delivery: Regulatory Trends. Available online: https://www.verdictfoodservice.com/comment/online-food-delivery-regulatory-trends/ (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Statista. Online Food Delivery. Available online: https://archive.is/e7OK5 (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Statista. Number of Employees Working in the Take-away and Food Delivery Industry in Japan from Fiscal Year 2016 to 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1230046/japan-employee-numbers-take-away-and-food-delivery-industry/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Uber Eats. Uber Eats’s Competitors, Revenue, Number of Employees, Funding and Acquisitions. Available online: https://archive.is/iP8Ss (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Rise. Why Are Food Aggregators Leveraging the Delivery-Only Model? Available online: https://archive.is/DhVHr (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Analysys. Annual Comprehensive Analysis of the Internet Catering Takeaway Market in China. 2019. Available online: https://archive.is/VKpJR (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Ma, Y. Current situation and solution of online food delivery in campus—A case study on students of Anhui Economic University. Mod. Bus. Trade Ind. 2019, 7, 50–51. [Google Scholar]

- The Spinoff. ‘Not a Level Playing Field’: NZ Restaurants Speak out on Uber Eats. Available online: https://archive.is/0hpR5#selection-1221.0-1221.66 (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- The Guardian. Uber Eats to Change ‘Unfair’ Contracts with Restaurants after ACCC Investigation. Available online: https://archive.is/HMtgR (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Uchiyama, Y.; Furuoka, F.; Md Akhir, M.N.; Li, J.; Lim, B.; Pazim, K.H. Labour Union’s Challenges for Improving for Gig Work Conditions on Food Delivery in Japan: A Lesson for Malaysia. WILAYAH Int. J. East. Asian Stud. 2022, 11, 83–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliverect. What Is a Dark Kitchen? Available online: https://archive.is/ap9FB#selection-469.0-469.23 (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Dailymail.com. Uber Founder Buys More than 100 “Dark Kitchens” across London in New Venture that Allows Takeaway-Only Businesses to Rent Them for £2500 a Month to Sell Food on Apps Such as Deliveroo. Available online: https://archive.is/jvJfl (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Choudhary, N. Strategic Analysis of Cloud Kitchen—A Case Study. Manag. Today 2019, 9, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Los Angeles Times. How Food Delivery Apps Have Changed the Game for Restaurants. Available online: https://archive.is/nzjpJ#selection-1693.9-1693.69 (accessed on 4 March 2023).

- Meenakshi, N.; Sinha, A. Food delivery apps in India: Wherein lies the success strategy? Strateg. Dir. 2019, 35, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuboh. The Rise of Food Delivery in Southeast Asia. Available online: https://www.cuboh.com/blog/food-delivery-southeast-asia (accessed on 4 March 2023).

- National Restaurant Association. Coronavirus Information and Resource. Available online: https://restaurant.org/Covid19 (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Brewer, P.; Sebby, A.G. The effect of online restaurant menus on consumers’ purchase intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2021, 94, 102777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlea-Schiopoiu, A.; Puiu, S.; Dinu, A. The impact of food delivery applications on Romanian consumers’ behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 82, 101220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Star. Food Delivery Services Will Thrive in 2020. Available online: https://www.thestar.com.my/food/food-news/2020/01/04/food-delivery-will-continue-to-be-a-big-trend-in-2020 (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Statista. Global Online Food Delivery Market Size 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/ (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Kerry. The Global State of Foodservice Market. Available online: https://www.kerry.com/insights/kerrydigest/2022/global-foodservice-market.html (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Poon, W.C.; Tung, S.E.H. The rise of online food delivery culture during the COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis of intention and its associated risk. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2022. ahead-of-print.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen McCain, S.L.; Lolli, J.; Liu, E.; Lin, L.C. An analysis of a third-party food delivery app during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 3032–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Wire. The Personal and Social Risks That India’s Food Delivery Workers Are Taking during COVID-19. Available online: https://thewire.in/%20business/COVID-19-food-delivery-workers (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Meena, P.; Kumar, G. Online food delivery companies’ performance and consumers expectations during COVID-19: An investigation using machine learning approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 68, 103052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Vu, D.C. Food Delivery Service During Social Distancing: Proactively Preventing or Potentially Spreading Coronavirus Disease–2019? Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2020, 14, e9–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilan, D.; Balderas-Cejudo, A.; Fernández-Lores, S.; Martinez-Navarro, G. Innovation in online food delivery: Learnings from COVID-19. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 24, 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Times of India. Delhi Food Delivery Boy Tests Positive for COVID-19: Should You Be Ordering Food from Outside? This Is What Doctors Feel. Available online: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/health-fitness/diet/delhi-food-delivery-boy-tests-positive-for-COVID-19-should-you-be-ordering-food-from-outside-this-is-what-doctors-feel/articleshow/75180601.cms (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Ahorsu, D.K.; Lin, C.Y.; Imani, V.; Saffari, M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pakpour, A.H. The fear of COVID-19 scale: Development and initial validation. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 20, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeble, M.; Adams, J.; Sacks, G.; Vanderlee, L.; White, C.M.; Hammond, D.; Burgoine, T. Use of Online Food Delivery Services to Order Food Prepared Away-From-Home and Associated Sociodemographic Characteristics: A Cross-Sectional, Multi-Country Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrolia, S.; Alagarsamy, S.; Solaikutty, V.M. Customers response to online food delivery services during COVID-19 outbreak using binary logistic regression. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Coco, G.; Gentile, A.; Bosnar, K.; Milovanović, I.; Bianco, A.; Drid, P.; Pišot, S. A Cross-Country Examination on the Fear of COVID-19 and the Sense of Loneliness during the First Wave of COVID-19 Outbreak. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.S.; Raeside, R.; Redfern, J.; Gibson, A.A.; Singleton, A.; Partridge, S.R. SupportLocal: How Online Food Delivery Services Leveraged the COVID-19 Pandemic to Promote Food and Beverages on Instagram. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 4812–4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dsouza, D.; Sharma, D. Online food delivery portals during COVID-19 times: An analysis of changing consumer behavior and expectations. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2021, 13, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, Y.T.; Tanto, H.; Mariyanto, M.; Hanjaya, C.; Young, M.N.; Persada, S.F.; Miraja, B.A.; Redi, A.A.N.P. Factors Affecting Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty in Online Food Delivery Service during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Its Relation with Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetta, L.D.; Hakim, M.P.; Gastaldi, G.B.; Seabra, L.M.J.; Rolim, P.M.; Nascimento, L.G.P.; Medeiros, C.O.; da Cunha, D.T. The use of food delivery apps during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: The role of solidarity, perceived risk, and regional aspects. Food Res. Int. 2021, 149, 110671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Zhu, Y. Why customers have the intention to reuse food delivery apps: Evidence from China. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baarsma, B.; Groenewegen, J. COVID-19 and the Demand for Online Grocery Shopping: Empirical Evidence from the Netherlands. De Econ. 2021, 169, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Think Global Health. Online Grocery Shopping during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Opportunities to Support Equitable Access to Food. Available online: https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/online-grocery-shopping-during-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- B.B.C. How Coronavirus Is Changing Grocery Shopping. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/future/bespoke/follow-the-food/how-covid-19-is-changing-food-shopping.html (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- The Guardian. UK to Ban Junk Food Advertising Online and before 9pm on TV from 2023. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/media/2021/jun/23/uk-to-ban-junk-food-advertising-online-and-before-9pm-on-tv-from-2023 (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- World Resources Institute. Paris’ Vision for a ‘15-Minute City’ Sparks a Global Movement. Available online: https://www.wri.org/insights/paris-15-minute-city (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Takeout and Delivery-Yokohama. What Is Takeout & Delivery in Yokohama? Available online: https://takeout.city.yokohama.lg.jp/ (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Coelho, P.M.; Corona, B.; ten Klooster, R.; Worrell, E. Sustainability of reusable packaging–Current situation and trends. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. X 2020, 6, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Country | Social Issues | References | Gray Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| USA |

| [41,42,47] | |

| UK |

| [43] | |

| China |

| [44,45,46,49] | |

| Japan |

| [53] | |

| India |

| [46,54] | [52] |

| Indonesia |

| [50] | |

| Global |

| [51] |

| Country | Environmental Issues | References | Gray Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| USA |

| [55] | [60,62] |

| Indonesia |

| [57,61] | |

| China |

| [44,58,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70] | |

| Japan |

| [59] | |

| India |

| [56,71] | |

| UK | |||

| Asia |

| [72] | [73] |

| Global |

| [74] | [75] |

| Country | Economic Issues | References | Gray Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| USA |

| [78] | |

| UK |

| [86,88] | |

| China |

| [70,81] | [80] |

| India |

| [87,89] | [79] |

| Japan |

| [84] | [77] |

| Asia |

| [90] | |

| Global |

| [47,82,85] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mitra, P.; Zhang, Y.; Mitra, B.K.; Shaw, R. Assessment of Impacts and Resilience of Online Food Services in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13213. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713213

Mitra P, Zhang Y, Mitra BK, Shaw R. Assessment of Impacts and Resilience of Online Food Services in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Sustainability. 2023; 15(17):13213. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713213

Chicago/Turabian StyleMitra, Priyanka, Yanwu Zhang, Bijon Kumer Mitra, and Rajib Shaw. 2023. "Assessment of Impacts and Resilience of Online Food Services in the Post-COVID-19 Era" Sustainability 15, no. 17: 13213. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713213