1. Introduction

The concept of collective creativity in design, commonly known as participatory design, until the recent emphasis on terms like co-creation or co-design, has been in existence for almost four decades. For instance, in the realm of urban planning [

1], product and service design [

2,

3], and also in game design [

4,

5,

6,

7] the participation of end users has surged, marking a significant shift in design processes.

Similarly, in the gaming industry, serious games as a tool to share educational content and provide learning experiences have gained popularity in recent years [

8] by leveraging the power of games for purposes beyond pure entertainment. Unlike other services, products, or solutions that usually serve a single purpose, a serious game is tasked with not only being fun and engaging but also raising awareness and educating the player [

9]. Serious gaming is proven to be effective in presenting complex topics, experimenting, and engaging a wide circle of participants [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Such games leverage game mechanics, interactivity, and narrative elements to engage players in meaningful experiences, fostering learning, skill development, or addressing real-world challenges. As one of their main purposes, serious games are thus believed to enhance opportunities for learning, practice and behaviour change [

14], aiming for so-called social learning [

15]. Reviews about serious games addressing the sustainability problems have shown that such social learning is frequently assessed through concepts of cognitive, normative, and relational learning [

15,

16], where “cognitive” refers to the acquisition of new or restructuring of existing knowledge; “normative” to a shift in viewpoints, paradigms or values; and “relational” to the ability to cooperate between stakeholders, enhancing trust and improving understanding of others’ mind-sets [

15].

Designing effective serious games requires careful consideration of various elements. Game mechanics should be aligned with the intended learning outcomes, providing players with engaging challenges, feedback loops, and rewards [

17,

18]. A carefully constructed storyline can deepen player immersion and foster an emotional bond with the game’s objectives and overall user experience. Simultaneously, intuitive interfaces play a crucial role in facilitating effortless adoption and encouraging sustained engagement [

19]. Moreover, involving target users in the design process through co-creation, co-design, and playtesting allows for iterative improvements and maximizes the game’s effectiveness [

20], as serious games often aim for social learning that is transferable to the world outside the game and can fit well with the learning-by-doing approach [

8,

15,

21,

22]. By employing collaborative and participatory design approaches, serious games can effectively integrate themselves into real-world situations. Such approaches facilitate the expression and translation of existing narratives, social conflicts, and institutional responses into a game context. As a result, serious games can become powerful tools for representing and addressing complex real-world issues [

12].

However, in the game development processes, the user-centric design approach is not common [

7]. Stakeholders can be involved in the game design process as users, testers, informants, and design partners fully incorporated in a co-design process, as is argued by scholars [

23,

24]. Still, game design approaches mostly engage potential players only for game-testing. The target groups and other stakeholders rarely participate in the early phases of the design process [

7,

20,

25,

26,

27] and user input and feedback are often gathered too far in the development process, limiting, for instance, the potential to optimise the balance between an engaging, entertaining game and its educational dimension [

9,

25]. On the contrary, in the participatory design framework, the target audience is already included in the earliest phases of the design process [

20].

Even though not yet widespread, the participatory design or co-design has already been recognised as one of the methods to integrate views, ideas, and needs of the target audience into the serious games by involving them in different stages of the game design process [

28]. The nexus between co-creation, co-design and serious game development has been increasingly researched, i.e., in [

12,

23,

25]. Serious games are designed to deliver specific learning outcomes or behavioural changes and this has led developers to explore more collaborative approaches that prioritise engagement and effectiveness to develop more relevant games. In the literature, the common notion regarding co-creation and co-design as a method to develop serious games is centred on its capability to embed real-world components in the game environment, while allowing participants of the co-design process to experiment and learn [

12,

28]. The co-design process helps to express societal issues in an understandable context by involving different stakeholders and combining their perspectives and views on the topic that the game brings to the player [

12,

29]. Even though no specific protocols exist for developing serious games [

30], co-creation and co-design have emerged as a way to incorporate diverse perspectives, ideas and expertise into the game design process, aiming to offer more engaging and impactful experiences, and several case studies have already shown that the co-design approach can be used to create serious games [

7,

12,

20,

27]. Furthermore, some argumentation exists that for understanding complex societal issues, not just serious games themselves but also the co-design process to create a serious game is an added value [

7,

23,

31]. Gugerell and Zuidema [

12] emphasise that this method facilitates learning throughout its use, meaning that the participants of the serious game co-design acquire knowledge about the topic while being engaged in the development process.

However, while the importance of co-creation and co-design in serious game development is recognised, there has been a relative lack of focus on their potential to initiate such learning events. It is more known that, for example, co-design has been used to develop game concepts and the initial idea, but less so for the mechanics of the game, gameplay, and other aspects [

15,

32,

33,

34,

35]. The emphasis has primarily been on addressing usability and playability concerns rather than exploring the learning and experimentation opportunities that arise from participatory game design processes [

7,

24]. Additionally, little attention has been given to the co-creation and co-design process itself in facilitating learning about the serious game topic among the participants, i.e., to the learning that happens during the participatory co-design activities [

12,

13,

24].

Even less research has been done on the co-design of serious games that deal with sustainable development, for example, few of them have been created in the fields of climate change, energy, or the environment, and what directly relates to the topic of this article, in the bioeconomy field [

13]. In addition, when it comes to the assessment of the effectiveness of the games that relate to sustainable development, then research has been scarce here as well [

11,

13,

15,

32,

33].

Developing a serious game is not an easy task and is complicated by the lack of knowledge about concepts, methods, and tools used to create them and lack of studies articulating the game design process [

6,

13,

28,

36,

37,

38]. Thus, there is the need for proven frameworks and tools to develop more effective serious games [

19] as well as evaluation approaches of participatory design processes [

23].

The current article contributes to the research on serious games that educate about sustainability and bioeconomy as well as about the use and benefits of co-creation and co-design approach in the game development process. At the centre of this study is the serious bioeconomy game “Mission BioHero” [

39] that was created within the Horizon 2020 AllThingsbio.PRO project [

40], the goal of which is to involve citizens in the bioeconomy and use their opinions on the topic to further develop the bioeconomy policies in the European Union (EU). This project focuses on four key themes in relation to bioeconomy that are part of daily lives: food packaging, fashion and textiles, kids and schools, and jobs and careers, all of which were incorporated into the developed serious game. The “Mission BioHero” game explains the bioeconomy and its connection to these four topics to citizens in a playful and engaging way. It consists of eight campaigns, each focusing on a specific theme that the player must achieve to save planet Earth. Co-creation and co-design were one of the guiding principles to develop the “Mission BioHero” game. This experiment is a valuable empirical case study to highlight the value of co-creation, co-design with end users and its potential impact on the design of a serious game in the bioeconomy field. The case study also highlights key lessons learned, since during the project implementation, the transformative power of co-creation and co-design in serious game development was explored, its benefits in terms of user engagement examined and learning outcomes and innovation analysed.

This article does not evaluate the effectiveness or impact of the serious game developed, since the needed amount of data for such analysis was not available after the immediate end of the project. The main aim is to understand the nature and influence of co-creation and co-design in developing a serious game for the participants, as well as the end result, i.e., the relevance and potential uptake of the developed game. The co-creation and co-design method was believed to be beneficial here, and the observations and empirical data gathered from co-creation and co-design phases, participants’, project partners’ (called mission partners), and external game players’ feedback have been assessed to find answers to the following specific research questions:

How successful were co-creation and co-design in developing the “Mission BioHero” game in terms of process and satisfaction of the stakeholders and what was driving this?

What was the (learning) value of co-creation and co-design to the participants?

What was the value of the co-creation and co-design to the outcome, i.e., is the co-designed serious game a useful tool as perceived by the target groups to learn about the bioeconomy?

The paper is structured in six main sections. First, theoretical concepts of serious games and notions of co-creation and co-design, including their expected benefits in the serious game design process, are explained. Further, a “Mission BioHero” case study is introduced and the methodology of the study is presented, followed by the analysis of the “Mission BioHero” development process and results. The last sections discuss the results, map the possibilities for further research, and provide conclusions.

4. Materials and Methods

The aim of the serious game designed in the AllThings.bioPRO project is to raise awareness of the bioeconomy and to educate the player on different bioeconomy-related issues in four mission areas (

Table 1). As a unique element, users were involved in developing this serious game from the very start through a range of focus groups, co-creation meetings and co-design workshops, which is, according to research, the main way of implementing co-creation and co-design with stakeholder groups. Evaluating the whole process was integrated into the overall work plan from the start of activities of the project to observe the process and reveal answers to the main research questions of current article. Evaluation was seen as a process of collecting evidence and reflection that helps to understand the dynamics, progress and effect of the work carried out, to learn from the experiences and to inform future initiatives and approaches. The methodology to assess the whole process and outcome of developing the bioeconomy serious game was along the principles of formative and summative evaluations. Formative evaluation aims at detecting areas for improvement, thus evaluating the process, whereas summative evaluation aims at determining to what extent an intervention was successful, thus judging its effectiveness [

32,

99,

100]. While choosing the evaluation tools, the research team took into consideration that especially in interventions aiming to reveal behavioural or attitude changes, two steps are important: a baseline assessment and a post-intervention assessment [

14,

49]. Central focus was also on assessing the effectiveness of co-creation and co-design via the participants’, developers’ and facilitators’ satisfaction with the process (see also [

64]).

As discussed above in relation to approaches to evaluate serious games as well as co-creation and co-design approaches to develop such games, the AllThings.bioPRO project opting for a mixed-method approach formed the foundation of the whole evaluation. Pre- and post-measurements were already included in the co-creation phases when the game did not yet exist and additional post-measurement done after the game had been designed and introduced to the participants and other external game testers in dedicated sessions. Further assessment of different aspects the game ultimately wants to achieve, like providing aggregated information about players’ demographics, bioeconomy knowledge, bioeconomy interests, etc., is done via in-game assessment mechanisms.

According to the posed research questions, selected evaluation tools were based on the need to concentrate on the satisfaction and effectiveness of the co-creation and co-design process, capturing the drivers of success or drawbacks, assess the perceptions of the participants about the value of such participatory design process as well as get first indications about the potential value of user-centred design to the final result, i.e., the game and its potential uptake. The overview of used evaluation tools is shown in

Table 2 and full details of these tools presented in

Supplementary S1.

Such variation in methodological tools allowed a complex assessment of the co-creation and co-design process, observing its benefit, drivers and downsides, as well assessing the value to the end result, i.e., the “Mission BioHero” game. Qualitative methods, such as interviews, focus groups, and participant-expressed open thoughts in the surveys and observations, allow us to gain in-depth insights into participants’ experiences with bioeconomy, perceptions, and emotions about it as well as learning progress during the participative game development process. These methods provide rich and nuanced data, enabling a comprehensive understanding of the co-creation and co-design activities’ effectiveness. On the other hand, quantitative methods via surveys help gather numerical data, such as satisfaction ratings, level of engagement, and performance metrics. These data provide a broader perspective on the game development and allow for some statistical analysis, enabling us to identify trends and patterns. By combining both approaches, a holistic view of the co-creation and co-design process is gained, validating and triangulating findings, and obtaining a more comprehensive and robust evaluation of the participative processes and serious game development. This mixed-method approach ensures the assessment is well-rounded and credible and can offer actionable insights for future improvements and iterations of the final product or for other similar processes.

5. Results

5.1. “Mission BioHero” Game Development Process

The “Mission BioHero” serious game was developed through the process of co-design, which is a part of a broader co-creation process. Co-creation and hence co-design follow an approach involving different perspectives and collaborative design tools, materials, processes, activities, or strategies, as discussed above.

The overall aim was to design the game in such a way that it would appeal to a wide range of target groups. The intended audience for the game encompassed civil society organisations, regional stakeholders, bio-based industry experts, game developers, and environmentally conscious individuals interested in sustainable solutions—thus, an enormously large and heterogeneous group. The co-creation process started in four bioeconomy-related missions (see

Table 1 above) in five different countries, where two regional project partners (assigned the role of facilitators) together with their recruited local citizen groups and regional economic, research, policy and civil society experts already active in the specific area of the mission co-developed the concept and design of the serious game. One can imagine the difficulty in narrowing down specific requirements and preferences in the game, as each of these eight subgroups (two per mission topic) had unique needs and expectations. The challenge was in finding a common ground that would effectively address the educational, informational, and entertainment aspects desired by the wide array of potential players (see also [

13,

28]).

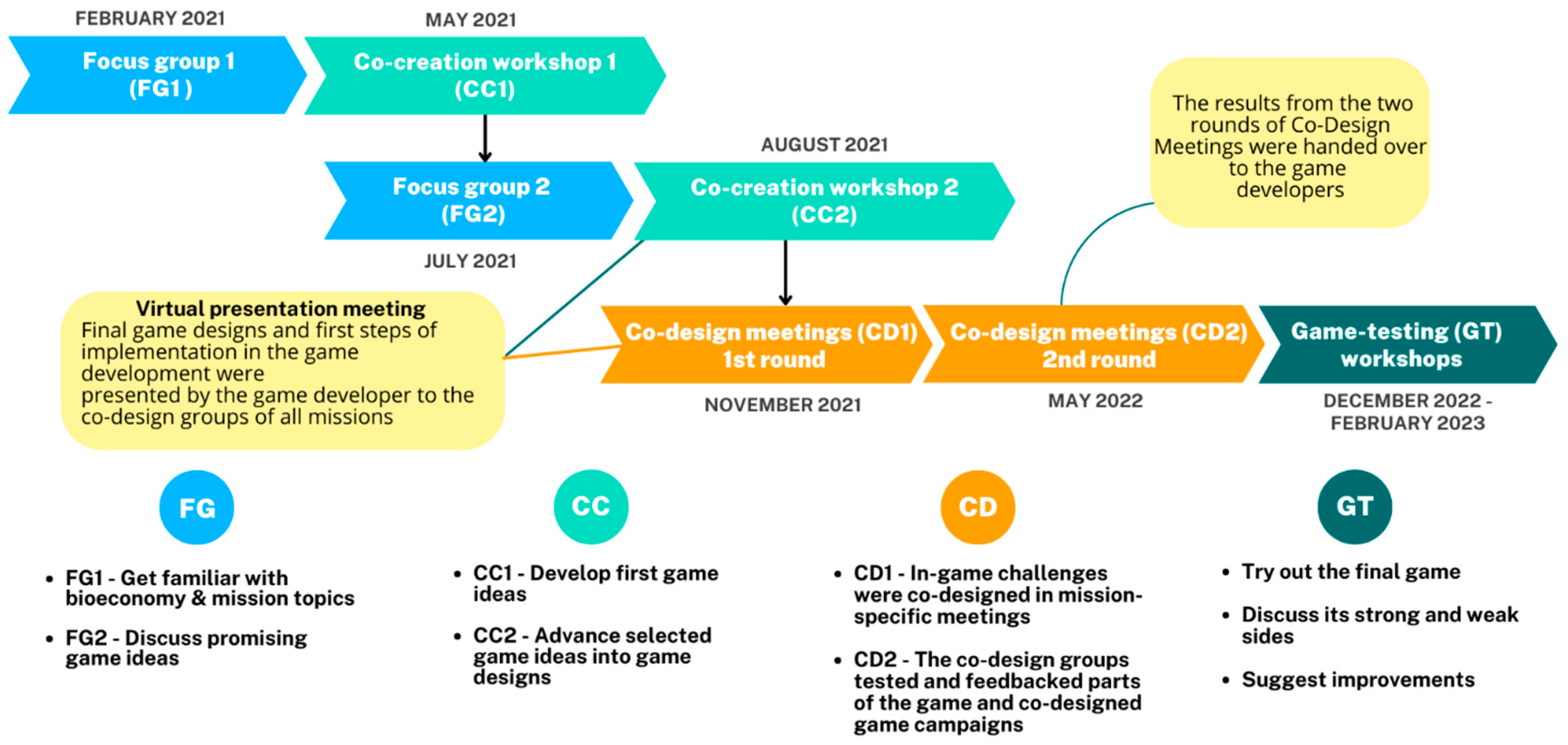

The process implemented within the AllThings.bioPRO project included several steps where the concept of the game and its purpose, logic, and visuals were developed together with the quadruple helix stakeholders. The co-creation and co-design process of the game included several phases with specific workshops, presented in more detail in

Supplementary S2. They were held by eight project partners in five different countries (Food packaging–Germany and the Netherlands; Fashion and Textiles–the Netherlands and Sweden; Kids and Schools–Germany and Estonia; Jobs and Careers–Germany and Italy) as the logic was that two regional partners work with the same mission topic (see

Table 1). The game development process was organised in two rounds of citizen focus groups and co-creation workshops together with citizens and field experts in the regions of the eight regional partners (co-creation phase), followed by two rounds of mission-specific co-design meetings (co-design phase), moderated centrally and held in English (see

Supplementary S2). While the co-creation was taking place in the eight regions in five countries of the regional partners in parallel, the two groups dealing with the same mission topic worked together in the co-design phase [

103].

In total, the co-creation and co-design process included 42 meetings. Initially, the focus groups and co-creation workshops as well as co-design meetings were planned to be run as in-person events. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all focus groups except for the ones in the K&S mission had to be held online. The involvement of the children’s group in the co-creation and co-design activities required extra preparations since the informed consent of their parents was needed as well as tools adjusted to better suit this target group. For example, the meetings with children were held in person and in their national languages (Estonian and German), since they were not fluent in English [

103].

The phases were run during March 2021–December 2022.

Figure 1 presents the “Mission BioHero” game development process and timeline schematically. A detailed overview of the step-by-step process of the co-creation and co-design activities implementation is described in the reports by Waltenberg and Steinhaus [

60,

103,

105] and in

Supplementary S2. A game developer was involved in all phases to answer questions from the groups about the game development technicalities, help to compile and comment on ideas for user requirements and game designs after the sequences of specific workshops, and support regional facilitators in preparing the next steps.

The full engagement phase was occurring hand in hand with the evaluation process that independently assessed the results of the focus group sessions, co-creation workshops, and co-design meetings. The results of this formative evaluation helped to gather information and assess mainly the success of the co-creation and co-design processes and the individual benefits for the partners and all participants in the process. This was followed by the summative evaluation through game-testing workshops and follow-up interviews with partners and participants to explore how relevant, acceptable, and sustainable the co-designed game was. The main findings gathered through evaluation activities are presented in the subsections below.

5.2. Preparations for the Co-Creation and Co-Design

The methodology for implementing co-creation and co-design in developing the serious game contained the following required elements: (1) a fixed sequence of focus groups, co-creation workshops, and co-design meetings; (2) clear aims that need to be achieved for each sequence; (3) in co-creation, a typical structure for each meeting that incorporates design thinking elements (design thinking takes a human-centred approach and consists of five stages: empathise, define, ideate, prototype, test [

69,

72]); (4) in co-design, a typical structure for each meeting ((1) welcoming the participants and introducing the objectives, (2) getting to know each other, (3) presenting the status of the game and app development, (4) questions, answers, and discussions, (5) co-designing mission-specific in-game challenges, (6) presenting the results, (7) summary and next steps [

103])) that focused on the later stages of game design, which builds on the conceptual game designs co-created in the previous phase; (5) recruiting a diverse participant group, which includes a mix of citizens and experts. The design thinking model was applied, which considers users’ needs and problems, challenges, and assumptions to create ideas and try out solutions. There is no singular concept of a co-creation workshop, but typically such workshops follow phases such as: (1) opening and familiarising; (2) diving into the topic; (3) ideating; (4) designing solutions; (5) closing; and (6) evaluating and reflecting [

71,

73]. These processes are typically not linear but iterative, and for each of these phases a variety of different methodologies can be applied [

106].

Most of the partners who had to facilitate the sessions in the co-creation phase had used the co-creation and co-design methodologies before, with some partners being relatively experienced with them and others having only limited experience. What was rapidly found as crucial to deal with parallel processes carried out by different facilitators and even in different countries was the setup of a central support structure by the overall process coordinator. Thus, the so-called co-creation working group was formed to meet virtually monthly, which dealt with the coordination of the engagement process, ensured proper implementation of the co-creation and co-design methodology, and organised the work of the HelpDesk. Next to the monthly working group meetings, the HelpDesk met every three months and consisted of the project’s experts who provided one-stop-shop support to regional facilitators and allowed for deeper reflections and alignments between development processes moderated by different regional partners.

In addition, before the start of the co-creation and co-design activities, an internal training was organised that reintroduced the project goals, game mission, and the tasks to be performed to the regional mission partners who were to organise the co-creation activities. At the beginning of the stakeholder engagement process, the central coordinator developed “Stakeholder Consultation Guidelines” [

106] to guide the stakeholder selection process as well as give an overview and guidance about the possible methodologies and tools that could be used within the focus groups and co-creation sessions. However, the focus group and co-creation workshop designs were tailored to the partners’ context, if needed.

Therefore, the partners were provided with instructional materials about the focus groups, co-creation and co-design meetings, and discussed their concerns during the preparatory and working group meetings. These components contributed to the thorough implementation of the planned activities and the engagement of the participants in this process. To engage the participants, the partners ultimately used creative approaches, a lot of brainstorming and ideation, like the creation of personas, game pitch documents, work in breakout rooms, etc. These activities also added learning value for the partners, and a richer list of them can be found in [

60,

105,

106].

Interviews with regional facilitators at later stages confirmed that the co-creation and co-design activity facilitators were mostly equipped to carry out the activities after the preparation phase. Regional moderators indicated that they highly valued the debriefing process after each round of activities, where the two partners sharing a mission topic could meet online and exchange their results and experiences. Similarities, differences, and individual focus areas were discussed. Further, all national partners came together across missions to discuss their results and experiences and reflect on them in their monthly working group meetings. This additional support from central coordinators and regular HelpDesk meetings to address overlapping challenges in different missions and regional groups also helped strengthen cooperation within the whole group and between mission partners.

5.3. Assessment of the Co-Creation and Co-Design Activities by the Participants

In the current study, the co-creation and co-design process participants are the people who were invited to take part in the process by the project members and regional facilitators. The participants were the local and international stakeholder(s) (groups)—actors from (civil) society, policy, research, and industry—actively and equitably involved throughout the whole process.

From the data of the follow-up surveys that were provided to the participants of the co-creation and co-design activities, most respondents felt that their ideas and thoughts were considered well when developing the “Mission BioHero” game (

Figure 2). In both the co-creation and co-design phases, the respondents also had positive comments and ratings about the workshop materials and content, and they indicated a high level of trust in the organisers by rating highly their personal data use and securing inclusivity.

Co-creation and co-design participants who were interviewed after the “Mission BioHero” game was launched in April 2023 also had the same impression (

Supplementary S9). The interviews were carried out to collect their assessment of the co-creation and co-design processes after seeing the final product (the game). The interviewees confirmed that their discussions during the activities had been fully considered. As stated by some participants:

“Most components that we have discussed (during the sessions), are there. We stuck to the collective decisions, so I saw the ideas we discussed put together.”

(Interviewee 8)

“We brainstormed and exchanged our ideas. This is how we inspired each other.”

(Interviewee 9)

Most co-creation and co-design activity participants found the activities to be enjoyable or very enjoyable (

Figure 3), which indicates that they were satisfied with the process and that it met their expectations.

The outcomes of the interviews with co-creation and co-design participants show that overall, the co-creation and co-design process was fun and interesting to attend. As stated by one interviewed participant:

“We started with a few meetings, brainstorming meetings with very different people. It was nice and challenging in a way. We came up with a few ideas, I was always participating because I was curious about participating. Additionally, it was environmentally oriented, so it was cool.”

(Interviewee 8)

However, some participants felt there could have been some improvements made in the process. For example, in their open-answer responses of the co-creation and co-design participants’ follow-up survey, they noted that the concept of the bioeconomy was not clear and the timing of the workshops that were mostly held in the evening was difficult for some participants because they were tired, and it was hard to focus. Indeed, as reflected by the workshop facilitators, levels of understanding and attitudes differed across and within the focus groups that started the co-creative phase [

60,

105]. As discussed above, knowledge differences and players’ motivation towards the topic and idea in the serious game are important to take into consideration [

11,

52,

53]. If this topic is not interesting or important to the target group, then they are unlikely to use the developed game. At the same time, one should not limit themselves to recruiting only knowledgeable or highly motivated participants for the co-creation and co-design processes, as also highlighted by Kristensson et al. [

59]. Having a rather heterogeneous group as co-designers is considered to be more valuable [

59]. Further, despite some participants who felt more “lost” in the underlying theme of bioeconomy, the overall knowledge about bioeconomy among “Mission BioHero” co-creators and designers was above average (see also

Section 5.4).

When it comes to the differences between the missions (food packaging, fashion and textiles, etc.), there were no significant discrepancies in the co-creation and co-design experience seen by the participants, except for the gender balance aspect. While the average assessment for decent gender balance was generally high, a few participants felt that there were too few men participating. This was particularly evident for the fashion and textiles mission. While a careful strategy to invite an equal number of men and women was implemented, in the co-creation phase, there were altogether still more women participating, but differences occurred within regional groups [

60,

105]. Diversity was much higher in the co-design phase, where over 100 participants were engaged in total [

103].

Rating whether the game concept considers the views of different cultures was most difficult for the participants, who either commented that they do not know enough about other cultures to assess this, or that it is difficult to say at this stage:

“I am unsure, as our co-design group was pretty monocultural. It would be good to have the game tested/reviewed by people from other cultures.”

(Respondent of the co-design follow-up survey)

The independent evaluation of the process by the authors of this article convinced us that the project actually kept its focus on cultural and overall diversity during the co-creation and co-design processes by setting a strategy of keeping a 50/50% balance between experts and citizens in co-creation and co-design workshops, recruiting a decent proportion of different age groups and having an extra focus on children’s participation through one mission topic. This was largely met with only a slight surplus of experts among all participants. Criteria like engaging a variety of stakeholder groups, engagement of public, institutional diversity, flexible attitudes to revise views and actions, changing responsibilities, and application of results and their specifications as stressed in Responsible Research and Innovation [

106] were considered to use in the stakeholder selection to be wide-ranging, diverse, include influential stakeholders as well as minoritised groups, and represent sufficiently many perspectives and groups to foster robust outcomes and to serve as an orientation for regional partners to select their stakeholders. The overall strategy to hold co-creation and co-design activities in different countries, developing game translations and promotion materials in several languages (besides English, also German and Italian), as well as testing the game with different target groups and nationalities, as also suggested by the interviewee above, all speak for the appropriate inclusion of various cultural circumstances, not to mention the careful observation to take cultural elements into consideration in the final game design. For example, based on the suggestions of the co-creation and co-design groups, the game developers endeavoured to create a gender-neutral non-human avatar in the game. Additionally, in the introductory video part, the narration is in English, but subtitles in all target languages are available.

Overall, around half of the respondents (there were 92 respondents of the co-creation and co-design follow-up surveys in total) evaluated the co-creation and co-design activities to be effective and dependent on the mission, 11–26% even very effective, children being most positive in their assessment (

Figure 4). The effectiveness was perceived as a multidimensional and referred to reaching certain decisions within the co-creation and co-design activities, implementation of the discussed ideas in the serious game or the learning experience that the participants had during the activities.

Feedback from the follow-up surveys provided some critical assessments as well. The critical feedback was mainly concerned with the efficiency of the co-creation and co-design meetings and the clarity of the result that was aimed to be achieved. As stated by one respondent:

“It was sometimes hard to know what we were supposed to achieve when it came to in-game challenges, topics, issues etc.”

(Respondent of the co-creation follow-up survey)

One mission facilitator reflected on this same observation in [

107]:

“We learned that it is crucial to communicate from the start what the timeline of the project is, what expectations or engagements there will be along the line, what participants will be contributing to, how their contributions will be used, and what they can get out of the experience themselves. This also needs to be reiterated and followed up on at different stages of the project.”

(Project partner and regional facilitator)

The lack of sufficient explanation about the bioeconomy concept and the inability to integrate the ideas that were created throughout the discussion were also mentioned by some participants. On the contrary, one interviewee highlighted that he would like to have seen more critical consideration to incorporate the ideas that were generated during the discussions as the wish to apply maximum of them can make the end result confusing:

“I develop the game myself and the co-design process was very fun to attend. […] Everyone’s idea was implemented, and I am not sure if it is a way to make the game. They were too inclusive of everyone’s ideas, and it was too much.”

(Interviewee 7)

Indeed, the professional game developer noted that they were not in a perfect position to fulfil the requirements of all sides and that one of the hardest was to effectively include feedback from all stakeholders. Thus, there is a need to find the right balance to mediate between the originality of ideas and making all participants feel that they have contributed and choosing between the ideas in order to design the final product.

This was ultimately rather successfully met in case of “Mission BioHero” [

10,

23], as all in all, participants were satisfied with the game they helped develop (

Supplementary S19), enjoyed the co-creation and co-design experience (

Supplementary S18) and perceived the effectiveness of the co-creation and co-design experience was high (

Figure 4). However, the comments overall also indicate that the participants value good and effective moderation and need to be aware of the purpose of their participation [

20,

79].

5.4. Co-Creation and Co-Design Participants Learning Outcomes

While the participants largely enjoyed the engagement process, assessing their personal learning was a more difficult task because of the limitations of the methodology used. To assess the bioeconomy learning experience among the participants, see [

14,

15,

51]. However, the response rate to the follow-up surveys was significantly lower (10%) than the baseline surveys and varied among missions (121 answers to the baseline survey and 41 to the follow-up ones were received in the co-creation phase, for example, the J&C group had the best balance (39/21) and the F&T group had the most baseline surveys (48) but the fewest follow-up surveys filled in (9)). It is not clear why the response rates were so low; however, as regional facilitators discussed, participants may have felt ‘participation fatigue’ given the number of events attended, too much time had elapsed between activities for some participants, or the follow-up surveys being administered via email may have led to a decrease in responses (i.e., easily ignored). Based on this feedback, the authors of this article had co-design participants take a follow-up survey during the workshop at the end of the last activity, where a much-improved response rate was achieved (see also

Supplementary S6 and S7). Moreover, there were some changing participants throughout the process who missed either the baseline or follow-up survey. Considering all this, qualitative feedback received from participants in formative evaluation served as the main input for drawing conclusions, being aware of the limitation that the method was relying on self-reflection of the participants’ knowledge, which can give only their own perceived assessment of their learning [

14,

15,

51].

According to the baseline survey (

Figure 5), most respondents felt that they had a medium to low-range understanding of the bioeconomy at the start of the process. Baseline respondents from the F&P mission indicated that they had the highest average level of understanding (5.7/10).

Figure 5 indicates that, as a general trend, there was a slight increase in knowledge of the bioeconomy across all missions.

While the small sample of the follow-up survey and above average knowledge and motivation toward bio-based options of the participants already in the baseline phase may account for such results about the bioeconomy knowledge, according to mission partners’ observations, their participants learned about bioeconomy, as these concepts were introduced and thoroughly discussed in every mission area. Such results were also reflected in the open-answer section of the co-creation phase follow-up survey and the follow-up interviews with co-creation and co-design participants. Some participants stated that they had diversified and deepened their already existing knowledge about bioeconomy through interaction with other participants throughout the engagement process:

“I have already paid a lot of attention to the bioeconomy topics, but I did pick up the knowledge from the people, who have been in the discussion group with me.”

(Interviewee 9)

“The activities allowed us to explore the subject further and share our findings.”

(Interviewee 8)

Additionally, when it came to the impact that the co-creation and co-design activities had on the participants’ attitude and behaviour toward the bioeconomy, then some clearly stated that they started paying more attention to the bioeconomy in their everyday life:

“I have been paying more attention when I go grocery shopping, for instance. Some of the elements have transferred to my shopping habits.”

(Interviewee 8)

Another important learning for the participants, according to mission partners, was learning about the mechanics and steps of serious game development. Participants familiar with gaming were especially interested in this, as they would not normally have a chance to contribute to such a field.

There were also single cases where the participants felt that their own bioeconomy knowledge was not sufficient to understand the topics of the co-creation workshops, emphasising that a thorough explanation of the topic was missing:

“There were a lot of discussions about the pros and cons of “bio-something”, a concept that was unknown to me, and that was never explained during the workshop.”

(Interviewee 7)

This shows that the activities should be planned in a detailed way, considering the baseline knowledge of every participant and providing explanations for every concept discussed during such activities. As reflected by the facilitators themselves, it was sometimes challenging that many co-creation participants did not join again in the co-design phase, and thus newcomers had to be informed about the state of the art, as sessions also included referrals to previous sessions. Thus, the collective learning was to keep this in mind and, as also asked by several participants, to send out questions/tasks in advance, for example, before the second round of meetings, to boost creativity and give participants the chance to prepare the sessions.

The gathered data mostly indicate that the co-creation and co-design process affected the participants so that they learned about bioeconomy and its related concepts, and serious game design.

5.5. Assessment of the Co-Creation and Co-Design Activities by the Project Partners and Regional Facilitators

5.5.1. Success Factors

The success of the co-creation and co-design activities from the perspective of the project partners relates to whether the results produced from these activities yielded helpful feedback and if the game was enhanced as a result of those processes. AllThings.bioPRO project partners and mission facilitators reflected their views about the participatory design process via moderator self-reflection surveys, bi-annual partner surveys, central co-creation working groups and HelpDesk meetings, and through interviews with the authors of this article (see also

Table 2 and

Supplementary S1). Their experiences in specific local missions were different in many cases [

60,

103,

105]; however, from their reflections, it can be concluded that the co-creation and co-design process was valued by all. Partners concluded that the co-creation events were enjoyable for the participants, the ones who participated were motivated and collaborated well, the results of the meetings were both creative and informative [

60], and the co-design phase was fruitful.

Partners carried out the activities with local stakeholder groups, and the results of these parallel participatory events (focus groups and co-creation workshops) differed from one mission partner to another due to differences in facilitators, participants, the partner’s expertise and local contexts [

105]. As reflected by the facilitators themselves, the differences in opinions and feedback from participants enriched the game results, for example, facilitated by discussions that were shaped by regional bioeconomy structures, personas shaped by regional cultural differences, game ideas inspired by national popular games etc. Thus, these differences were considered valuable, as this way, more perspectives and local differences could be taken into account in the handling of one mission topic [

64].

Regarding the co-creation phase, regional facilitators felt that in general, the focus groups and co-creation workshops were carried out effectively and were pleased with the level of participation from the participants (

Figure 6).

Some takeaways from the co-creation phase for the facilitators were that there was high enthusiasm and motivation to contribute and create among the groups; participants enjoyed the playfulness of the events; all workshop groups came up with highly creative and unique game design ideas; and working in small groups (also in breakout rooms) gave more space for individual input and interaction. Virtually all moderators of the co-creation activities agreed or somewhat agreed with the statements that the “participants seemed interested and active” and “the participants participated actively” (

Figure 6). Most felt that the activity was productive, even if there were a few participants in some meetings who were less engaged.

In their self-reflection surveys (this self-reflection survey was not done in the co-design phase, since the co-design activities were coordinated centrally and responses gathered in bi-annual surveys and interviews reflect the experiences during the co-design activities.), facilitators noted that the range of ideas and creativity exhibited by the participants exceeded their expectations and helped them to understand the needs and expectations of the “Mission BioHero” game target groups better. As illustrated by one facilitator:

“The event exceeded all our expectations and hopes. The group unleashed great creativity and energy and developed team spirit. The team developed an enormous number of creative and unique game ideas. The event lasted for 4 h with only 5 min (!) break. Still, people were excited to continue working on the ideas and said time flew by and it was a great pleasure to participate.”

(Facilitators’ self-reflection survey respondent)

Regional facilitators recorded that the key success factors of a co-creative process were equal collaboration between stakeholders and relevant and continuous information sharing. In practice, this means ensuring everybody’s voices are heard and opinions valued and that everybody is constantly in the know of what is and will happen. The participants need to feel like they contributed something valuable and that the co-creation is not only a one-time thing: they need to be kept informed of progress even after the participatory phase ends. As stated by one partner in the survey about lessons learned [

107]:

“It takes time to engage and build trust but processes should not be too long. Participants need to have regular feedback and incentives to engage.”

(Project partner and regional facilitator)

Attempts to ensure openness and transparency were incorporated into the design process of “Mission BioHero” serious game. For example, “between the first and the second round of co-design meetings the regional partners stayed connected with the co-design groups and sent regular updates on the game and app development. At Christmas 2021 the AllThings.bioPRO stakeholders received a Christmas card and a two-pager with a summary of results from the first round of co-design meetings and an outlook into the activities in 2022. In March 2022 the stakeholders received a comprehensive report on the status of the game and app development including the uptake of their ideas. Although, this overview and report were not a part of the initial plan, the consortium deemed it highly important to stay in touch with the co-design group.” [

103], p. 25. These practical steps were important. Indeed, surveys and interviews with the participants also showed that they felt included, well informed, and considered their opinions to be valued by the organisers and the whole group (see also

Figure 2).

Designing the “Mission BioHero” serious game is an interesting case because it included children as one target group to design the game (co-creation and co-design events were held with children aged 10–14; altogether, 8 children participated in the co-creation phase, 27 in the co-design phase and 5 in the game-testing phase (see also

Supplementary S5, S7 and S8)). Some other scholars have highlighted that efforts to engage children as co-designers have presented challenges that necessitate sustained involvement using appropriate tools and techniques tailored to their developmental stage and the specific study context. Previous research has highlighted recurring issues such as limited creativity, unfocused or irrelevant ideas, and the inclusion of violent content, which directly contradict the educational objectives of the game. These challenges have been attributed to children’s insufficient domain knowledge and their limited literacy in game design principles. Therefore, there have been claims that children should be constrained to the role of informants [

71,

108] and not true co-designers [

33]. However, these observations for child participants were not observed in the current study. Even though engaging children from two different countries, Germany and Estonia, was challenging, as engagement and evaluation had to be adjusted to them and also totally separate co-design meetings in their own language were held compared to others that were centrally coordinated and held online in English, these meetings were valuable. Children generated great ideas, learned from the sessions (see also

Figure 5 and

Supplementary S15) and provided valuable constructive critiques to modify the game when it was adjusted for educational purposes [

60,

103,

105]. Moreover, some of their ideas were integrated into the game. For example, they designed polluted and healthy versions of the Earth, different suggestions for the avatar and other in-game creatures, equipment and accessories were included, and the main theme in city builder, where the player wanders around a game map and can zoom into different worlds to learn about different environmentally friendly solutions and products by solving different tasks or day quests, came directly from the co-design sessions with children. A statement from the game developer is more than illustrative here:

“Their (*children) feedback is very open, direct...even more valuable experience for us./…/Even if you design something for children then it’s usually for leisure or entertainment purposes. But for here, it’s a new perspective/…/”

(Interviewee 2)

Further, for the game developers, being engaged in the co-creation and co-design process was a new experience, and some scepticism was noted in the first interview with the developers (similar to what is described in [

25]). As stated above by some research, interviews revealed that the game design process normally takes a top-down approach, where internal brainstorming and ideation processes are undertaken by a core team, then the game is launched. This participative process implemented in the case of “Mission BioHero” allowed the developer to connect with their potential users, learn about the topics being discussed, and identify creative ways to include their feedback in the game. This was also reflected in one of the interviews with the game developer:

“We do not have access to the target group. That is why research projects are interesting for us because we can test with the target group. New perspectives, experiences, game development, process etc. For us, it was a benefit to be able to test with the target group.”

(Interviewee 2)

It was mentioned that without this process, the game designer would likely have omitted many of the mission topics because it would have been too difficult to include everything in one game. However, with the assistance of participants in the co-creation and co-design process, they were able to co-create solutions and include all four mission topics in the game. Moreover, the interviewee mentioned that co-creation and co-design were helpful for understanding the “general feeling” and “which direction” the participants would like to take the game. The participants’ feedback was also enlightening for the game design team in that it allowed them to better understand the types of games that are popular for their potential user base. This is because the participants, some of whom are active gamers themselves, have a pulse on what types of games are popular, and this feedback can then be used to help the design team create a game that better matches the current gaming trends. The value of co-creation and co-design is seen to be especially important in serious game development, which has to balance between leisure and education. For developing content and securing the educational component of the game, the inclusion of thematic experts is as important as inclusion of representatives of broader target groups.

Usually, game developers will not be able to measure the success of a game until they hit a critical mass of responses from the game users, measured in downloads, playtime, drop-off rate, etc., which is generally in the thousands. The co-creation and co-design process engaged a smaller pool of participants, which usually means that the opinions of these participants should be taken with “a grain of salt” until sufficient quantitative data can be collected. However, despite contradicting such industry norms, the game designer clearly found value in using a participatory approach for developing a serious game.

5.5.2. Challenges

The co-creation and co-design process has also shown several challenges. One of the biggest challenges in many participatory design processes is recruiting and keeping the participants [

37]. Self-reflection surveys as well as survey about lessons learned [

107] among the project partners show that during the co-creation workshops and co-design meetings, some participants dropped out of the process. It was discussed in project meetings that this could be due to tight timing, little compensation, and a lack of clear benefits for the participants, although the strategy was to keep the same participants over the course of the entire engagement process. Only one mission was able to keep most participants throughout the whole sequence of the co-creation and co-design phase. It was especially difficult to engage the same participants from the co-creation phase.

Supplementary S17 illustrates the retention rate throughout the co-creation and co-design process of “Mission BioHero”. The main reason considered here was the long time between the events. Each participant had the opportunity to attend six total events: four co-creation activities and two co-design workshops. It was originally planned to have the same participants attending every event; however, most participants attended only one event.

In the co-design phase, the number of returning partners from co-design round 1 to co-design round 2 was quite satisfactory and almost all co-design participants attended both events (

Supplementary S7). This can be explained by the early recruitment of the participants, good information flows as well as gained experience of the activity organisers and mutual constant reflections. The actual retention overall influenced the size of the target audience that was initially planned, but according to partners’ reflections did not have a crucial impact on the final product, and all in all the missions were completed still with a satisfactory participant group.

The regional facilitators used their own networks to recruit participants and were instructed to include both citizens and experts. As assessed by the workshop facilitators themselves [

105], among the experts, it was much easier to mobilise representatives from science and academia or civil society than from business, industry, and policy. For example, one partner stated:

“It was much more difficult than expected to keep citizens and experts onboard. The time between events and the fact that experts found it difficult to see the added value for their business, meant that the number of participants decreased.”

(Facilitators’ self-reflection survey respondent)

It has been found that effective co-creation and co-design processes would need to engage heterogeneous groups as diversity of thoughts at the beginning of a product or service development project often leads to innovations [

59,

68]. This was one of the baseline ideas also in the “Mission BioHero” development process. However, and as already discussed above, some concerns over sufficient diversity in the participant groups were raised, especially in the co-creation phase. Even though a lot of attention was put on guiding the partners in stakeholder recruitment by providing guidelines [

106] and HelpDesk support, it remained challenging to reach and keep a decent balance of stakeholders in the process. For example, it was collectively assessed in [

103] that it was difficult to reach representatives from minoritised groups with “silent voices”. “If we were to repeat the stakeholder selection, we would increase attention to specialised mobilisation and communication strategies (formats, language, channels, locations) to reach minorities. Additionally, we would decrease the time between the meetings to increase the rate of repeat participants. If this is not possible, the planning of other activities to keep participants interested and involved during the engagement events could be helpful. Further, more concrete incentives and personal benefits from participation could have improved the stakeholder selection.” [

103], p. 37.

Another challenge from the moderation side of the co-creation and co-design meetings includes difficulties with setting up an online meeting and engaging participants in an online format as well as that too many activities were on the agenda. Events were moved online, but participants usually are not willing to spend as many hours in an online meeting as they would in a physical one, which meant still trying to address everything on the agenda, but having to do it in a shorter amount of time. Further, most facilitators said that they would allow more time in future meetings and try to overcome any difficulties they had from re-occurring. Further drawbacks to online participation include not being able to get to know each other, difficulties with keeping participants engaged, different group dynamics as opposed to face-to-face meetings, and technical challenges in terms of using online tools and meeting platforms. Some partners mentioned that taking a “hybrid approach” and having some online meetings and some in-person meetings would be a nice option. This way, the participants could get the benefits of both styles of meetings, and they can optimize the time that is spent together, build trust, and foster communication and connections between engaged participants.

While some partners felt that in-person meetings would have worked better in terms of being able to build better relationships with participants and have larger turnouts, there were benefits to having to adapt the process to this sudden change and the feasibility to co-create online by regional partners was reported. The shift to online activities resulted in the partners learning new (online) methods and tools and widening their contact networks due to online events not being restricted by having to be physically present. The online format also enabled mission partners to observe each other’s events whenever the language barrier was not an issue, which was an important means of experience exchange and mutual learning. Additionally, missions were able to engage people from other regions and countries and were not limited because of travel constraints (especially important in the co-design phase). Sometimes, online meetings were more convenient for the participants as they could attend them from the comfort of their homes and could easily fit their schedules.

5.6. Co-Creation and Co-Design Facilitators’ Learning Outcomes

As stated above, in the research still little attention has been given to exploring how co-creation and co-design processes themselves facilitate learning that happens during the participatory co-design activities [

12,

13,

24]. With regard to learnings for the mission partners/workshop facilitators, these were recorded via the biannual surveys, partner interviews, and joint discussions during project meetings. Many partners mentioned gaining new personal skills while using co-creation and co-design. Most often mentioned learnings were new engagement and participation methods and methodologies (including online methods and tools); new knowledge of project management and communication; knowledge about (serious) game development and gamification; new skills regarding creativity and creative thinking; and new knowledge about bioeconomy and its relationship with other topics. As another positive aspect, a few respondents mentioned sharing their new skills within their teams as well:

“I have learned about engagement and creativity methods, which will be of use for my team as well.”

(Project partner, bi-annual survey 1)

Several partners mentioned a notable increase in the capacity of their organisation or other positive effects on their organisation while using co-creation and co-design. These include opportunity to reach their target groups in a new way or to reach a broader target group than previously; more in-depth knowledge of bioeconomy topics; a new and/or improved image of the organisation as one that works with the topic of bioeconomy; increased visibility and publicity; knowledge of EU projects and capability to implement them, e.g., regarding project management and workflows; new skills regarding online participation methods and online communication in general; knowledge of new methods and tools, e.g., regarding (online) co-creation and co-design tools; learning to use new formats to target new audiences.

Several respondents also mentioned new cooperation opportunities because of the co-creation and co-design experience. These have come both in the form of new contacts with new stakeholders, but also as opportunities for greater visibility, for example, invitations to new collaboration projects, or to conferences and meetings. Several partners mention improved networking:

“We were brought in contact with citizens and groups we did not have much relationships with before the project.”

(Project partner, bi-annual survey 4)

Indeed, in one of the latest surveys among the partners about the lessons learned from the co-creation and co-design process, knowledge transfer and reaching out [

107] almost all indicate notable positive impact mentioning increased connection and interest from other projects and networks; several mention increased contacts to school networks, big brands and governmental organisations as well as the Bio-Based Industries Consortium (BIC).

Another interesting aspect of the feedback received through the biannual surveys (the description of this methodology part can be found in

Supplementary S1) was being able to identify how learning new skills increased from the first survey and throughout the project (

Figure 7). Naturally, at the start of the project, one would not have many experiences to cite specific knowledge or growth; however, as the project progressed, so did the learning outcomes. Shown in

Figure 7 below, the number of learning experiences (indicated by a partner responding that their organisation or themselves personally had learned something new) increased from the first two biannual surveys to the later biannual surveys (BA), indicating that over the course of the project, learning outcomes at an organisation and individual level increased.

On average, an increasing number of partners indicated that they had learned something by participating in project activities. In general, affirmative learning experiences were consistent from BA3–BA5 in both scenarios (

Figure 7). A reason for a possible decrease for BA5 in both cases was that for some partners, their primary facilitation activities had ended, so they were not as actively in contact with the co-design participants anymore. However, when the project was most active (co-creation phase and BA3–BA4), most or all partners indicated that they had learned something new to the benefit of their organisation or themselves.

Thus, mission partners noted considerable growth and learnings in various areas both professionally and personally. As such, the engagement process provided many opportunities to learn, adapt, and gain new skills for the regional facilitators and coordinating partners in the process.

5.7. Result of the Co-Creation and Co-Design Process: The “Mission BioHero” Game

The goal of the thorough application of co-creation and co-design in AllThingsbio.PRO has been to develop a serious game, that has the potential to be utilised to foster citizens’ awareness, participation and co-creation of the future of bioeconomy. Thus, the reflections about moving towards this goal were evaluated throughout the process (formative evaluation). Even though at the end of the co-creation phase the game design shown to participants was not yet complete, the enthusiasm of the participants was high. The co-creation groups came up with eight game designs, which they handed over to the professional game development team. After careful analysis, the team decided that instead of deliberately splitting the four missions (see

Table 1) within the game world, they should be more interconnected. This means that players would have the chance to play content from different missions simultaneously. This decision was influenced by recurring elements found in the game designs from the co-creation phase [

103]. In the end, elements from all four missions were included in the overall game design. The J&C group developed the game’s narrative, the K&S group designed the in-game world and the avatar, the FP group contributed to the city builder mini game, and the F&T group contributed to the real-life and in-game tasks. Additionally, ideas such as multiplayer options, educational aspects, quizzes, happiness points, and the ability to train and unlock skills were integrated into the game based on suggestions from multiple groups [

103]. As a result, the mission topics are not represented separately in the game, for example, through four distinct mini games. Instead, they are interconnected through the campaigns

(Figure 8).The reflections of co-creation and co-design participants were captured after the co-design meetings, as there, the participants had a chance, first, to work on with the game designs handed over from the co-creation phase and, second, to see and try out the first game designs after the adjustments during the co-design phase.

Their first impressions were mostly positive, and most respondents felt the game they helped design was visually appealing; most respondents gave above-average rankings for the intuitiveness and ease of use for the game; indicated they would play the game on a weekly or monthly basis and most respondents indicated they would recommend the game to others (

Supplementary S10–S13). Moreover, respondents for the J&C, F&T, and FP missions mostly felt that the game would help the players learn about their specific mission topic (scores in range of 7.2–8.4 from 10), but at this stage had mixed opinions about whether the game would be effective in encouraging users to search for a career in the bioeconomy; wear and/or shop for bio-based clothes; or encourage people to purchase bio-based products and bio-based packaging (scores in range of 6.2–7.4 out of 10). This was an important indicator because one of the goals of the game is to induce a behavioural change with regard to environmentally harmful practices and towards more circular/bio-friendly habits and practices.

At this stage, there were also more critical statements and doubts, especially from the K&S mission. As referenced in

Section 5.5, feedback from children was generally more blunt, honest, and provided a new perspective for the game designer, participants stating that they would either never or only yearly play the game. While children are normally avid gamers, this outcome may also be somewhat expected, as most children do play games regularly and as a result, are likely to have specific preferences or expectations in place when it comes to games. Some children even noted that it was not the “type” of game that they enjoyed. Several respondents among children felt the game was difficult and confusing to use and more guidance would be needed to progress in the game.

As indicated, the game design at the end of co-design phase was still in the status of very first prototype, all feedback was valuable for the professional development team and was taken into account when adding improvements to the game. The co-design feedback sessions showed that the objectives and reasons to play must be made clearer (in-game and transfer to real life). Further, the game needed a proper introduction (intro and outro video were added based on feedback), step-by-step instructions and tutorials, especially in the city builder mini game, because the target groups are not experienced gamers, but citizens interested in sustainable lifestyles. The game developer also had to make efforts to make the game more fun and less informative. Learning processes were suggested to be improved, e.g., by optimising the explanations for right and wrong answers [

103]. An option of introducing a “kids’ mode” was also brought up for evaluation and potential future integration in the game, after the initial data of interactions with the game is evaluated.

5.8. External Game-Testing Results

5.8.1. General Feedback about “Mission BioHero” User Experience

The developed “Mission BioHero” game was tested with external stakeholders by the authors of this article during a series of game-testing workshops held in December 2022–February 2023 (see

Figure 1). The workshops gathered children, university students and adult participants who have some interest in bioeconomy (see

Supplementary S8 for more details).

When it comes to the evaluation of the co-designed “Mission BioHero” game among the general audience, who did not take part in the co-creation and co-design activities, then the overall impression of the respondents about the game was either positive or neutral. During the game-testing workshop discussions, the results of which were gathered also on Padlet boards and in their feedback the participants mentioned that they liked the overall idea of the “Mission BioHero” game, i.e., saving the Earth (see

Figure 9), and the diversity of different tasks that it offers, the information presented in the game was noted to be relevant; and the look of the game was described as nice, but needing improvements regarding the quality and style of the graphics.

A serious game should be adaptable and respond to the users’ needs within the game, i.e., level of difficulty, and provide a positive user experience [

110]. To this end, several questions were asked to game-testing participants (62 participants in total) to understand the user experience, where the participants were asked to evaluate their experience on a scale between poor, average, good, and not sure (

Figure 10). The “not sure” option was hardly chosen by the game-testing workshop participants and was estimated to be less than 1% of the responses.

Graphics and visuals, installation, and setup were highly rated, which indicates that these elements of the game were positive. The same applied largely to the story/narrative of the game. Controls and navigation, tutorials and instruction, and the gameplay are the aspects that the workshop participants were less satisfied with, and which indicated for the professional game developers that more attention has to be put there.

Some of the main issues with the game aspects were related to the difficulty of the game, especially the quizzes. 40% of the respondents agreed or rather agreed that the content of the game and its questions were difficult, and 49% found them somewhat challenging (see

Supplementary S14 for more information). Especially difficult was this task for children, who did not understand the bioeconomy definitions well (four out of five children participants found the game difficult, more info in

Supplementary S15). Additionally, the complications were caused by the fact that it was not possible to see all answers that were wrong and explanations to why they were wrong. Some difficulties were seen with the user interface faced with dragging and clicking on the icons, which are quite small and require preciseness, overall glitches, and occasional unresponsiveness of the touch screen. This was important feedback. At the same time, it is also important to point out that one does not need to be an expert to play the game. Rather, the purpose of the game is to educate players about the bioeconomy. As such, while the feedback might have been negative about users` understanding of the game, a longer-term study of the educational impact may have shown an increase in their knowledge about the bioeconomy. In fact, most respondents felt they had learned something about the bioeconomy after playing the game (

Supplementary S14).

The design of the game received the most positive assessment; however, there still were several remarks about it, like the unreadability of some fonts and the clumsiness of some graphics. Another problem that the participants faced and stated in their feedback was that it was difficult to understand and make progress in the game because many actions that the game missions require needed prior explanation.

Based on the game-testing participants’ feedback, the game developers already have applied further changes in the game, for example, the most difficult questions were removed and/or fewer answer choices were given in the quiz. The simple “Not all answers were correct” screen has been changed so that it is now clear which answer was selected and whether it was correct or incorrect (

Figure 11). Some questions or answer choices have been changed or removed because they were incorrect or ambiguous or that some user interface elements have been adjusted and the bugs fixed. Within the scope of the project, project partners who have more knowledge in the bioeconomy have been able to provide updated content and text for the game developer to make the instructions clearer. Further, an instructional handbook for educators [

111] was developed that would explain how to use the game in an academic setting, i.e., teaching students about the bioeconomy using the game.

5.8.2. “Mission BioHero” Educational Potential

The educational aspect of the game, which was evaluated during the game-testing workshops through the discussion of the participants’ learning experience and their view of the applicability of the game in the educational framework, showed its potential effectiveness to teach bioeconomy topics. To see how the game was experienced by the game players, the difference between the players with high and low levels of knowledge about bioeconomy was looked at, which brought the following findings (see also

Supplementary S16 for more details):

44% of the participants with a self-assessed low–medium bioeconomy knowledge level feel that they have learned more about bioeconomy while playing the game, while among the participants with a high bioeconomy knowledge level, this indicator is only 17%.

60% of the participants with self-assessed high bioeconomy knowledge levels think that the game will have a considerable impact on the players’ knowledge about bioeconomy.

Moreover, to assess the learning potential of the game, game-testing participants were asked to rate their learning experience with the “Mission BioHero” game. As seen in

Figure 12, game testers’ perceived learning outcomes were viewed as mostly positive, with most of the respondents selecting “Somewhat” followed by “Rather yes” or “Yes”. The exception to this trend is indicated in the second statement, where more respondents indicated that “Yes” they feel like they know more about the bioeconomy after playing the game.

While further studies would need to be conducted to understand the full learning impact from the game–including knowledge retention–the responses provided by game testers as well as interviewees are mainly positive (see

Table 4). The feedback received underscores that the information about the bioeconomy was communicated in such a way that the users were able to learn about the sustainability and bioeconomy topics, which further supports the effective integration of these concepts and the potential of the game as a learning tool.

5.8.3. Potential Uptake of “Mission BioHero”

During the co-creation and co-design phase and in parallel with the activities with the design partners from the civil society and other field experts, discussions with the bioeconomy uptake community experts were held, since among others one of the ultimate aims of the whole undertaking was to exploit and further develop the AllThings.Bio Platform [

40] for bio-based economy communication to the broader public by linking it with the serious game, and a European Bioeconomy Citizen Action Network. The intention was to ensure engagement and uptake of developed results through an early and regular involvement of regional partners and citizens as well as of key bio-based economy stakeholders, policy-makers and the Knowledge Centre for Bioeconomy (KCB) [

112]. These stakeholder groups were referred to as the uptake stakeholder community from the fields of industry and consumer protection, civil society and environment, policy and government, education, research and media and are considered “key potential users” of the data coming from the serious game (detailed overview about the uptake strategy and mapping of key potential users of project insights, their engagement process and results are described in AllThings.bioPRO public project deliverables [

101,

102,

112]). Their inclusion aimed to find out what wishes the uptake experts have about the serious bioeconomy game and what results they expect it to bring. The summary of some main expectations are presented in the table below (

Table 5).

From

Table 5, it is visible that the expectations of the experts were largely met and reflected in the “Mission BioHero” game, but still, suggestions for improvements for impact increase were noted. For example, in some bilateral interviews with experts (these interviews were conducted by Prospex Institute and anonymous quotes from experts shared with the authors of this article for the purpose of the research, see also [