The influence of Socio-Psychological Factors on Residents’ Willingness to Practice Sustainable Waste Handling in Dammam City, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Problem Statement

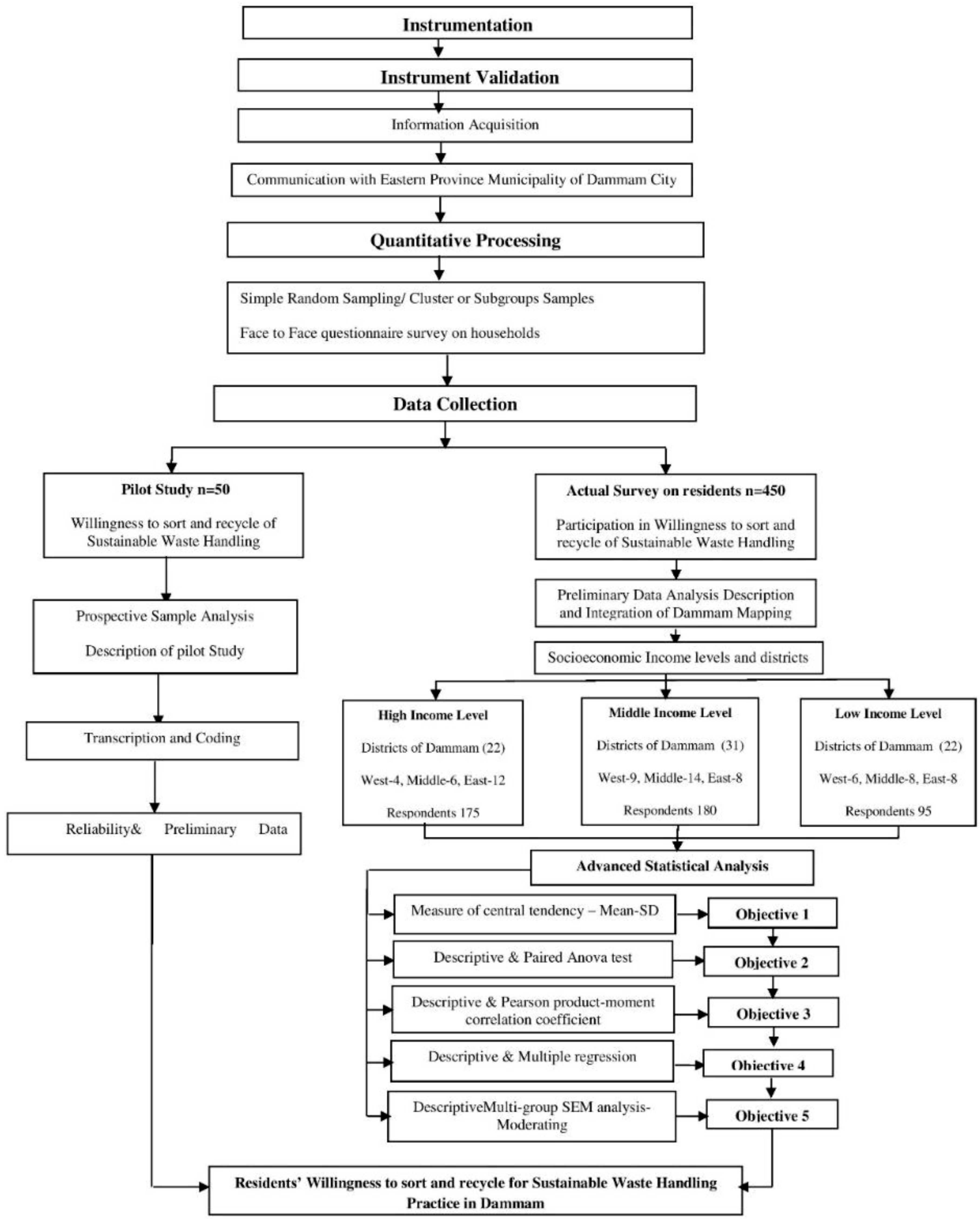

4. Focus on the Study

5. Methodology

6. Results and Discussion

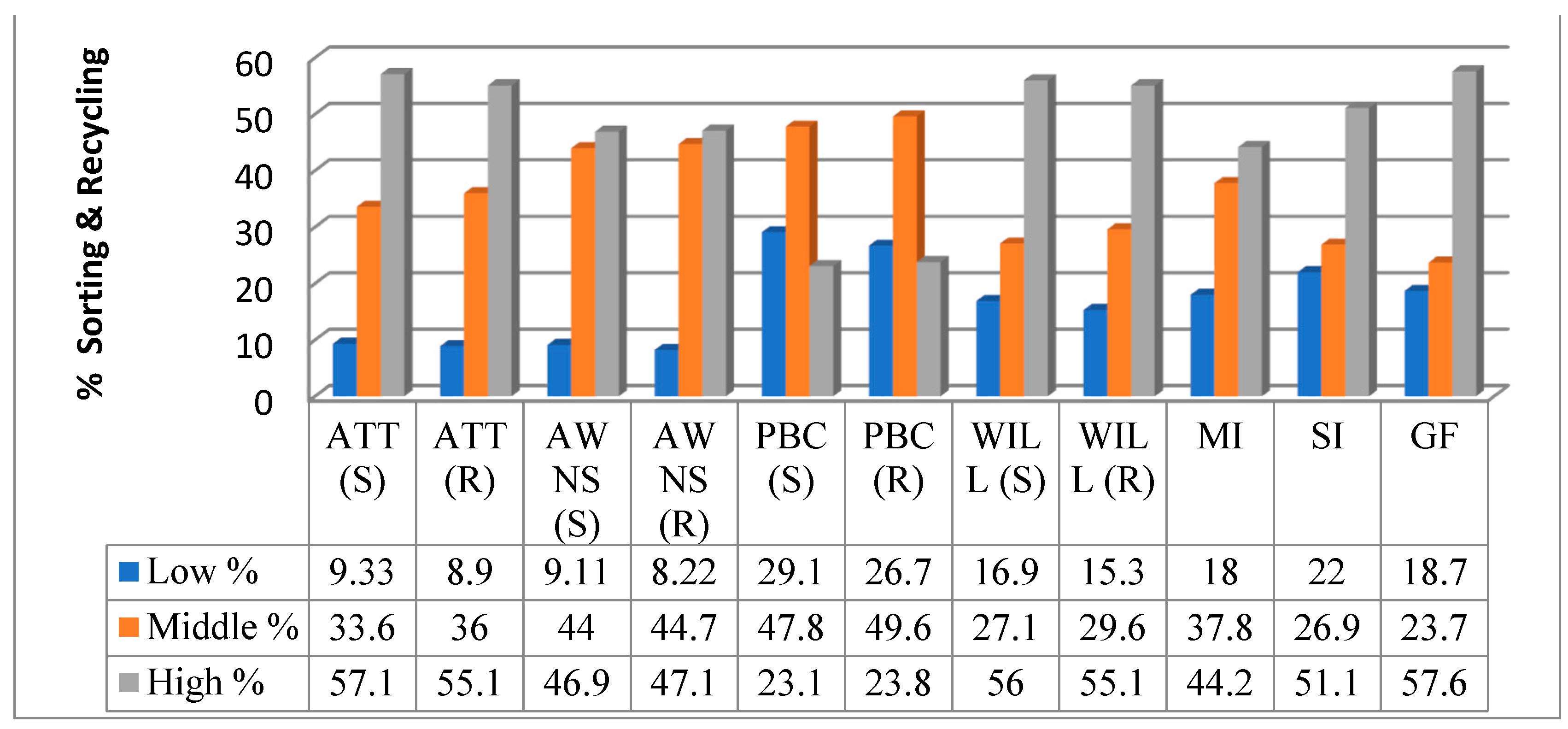

6.1. Levels of Variables of the Study in Sorting and Recycling

6.2. ANOVA-Test Analysis to Compare High-, Middle-, and Low-Income Groups on the Variables of the Study

6.3. Comparing the Three Different Income Level Groups with Dammam City Residents’ Psychological Factors

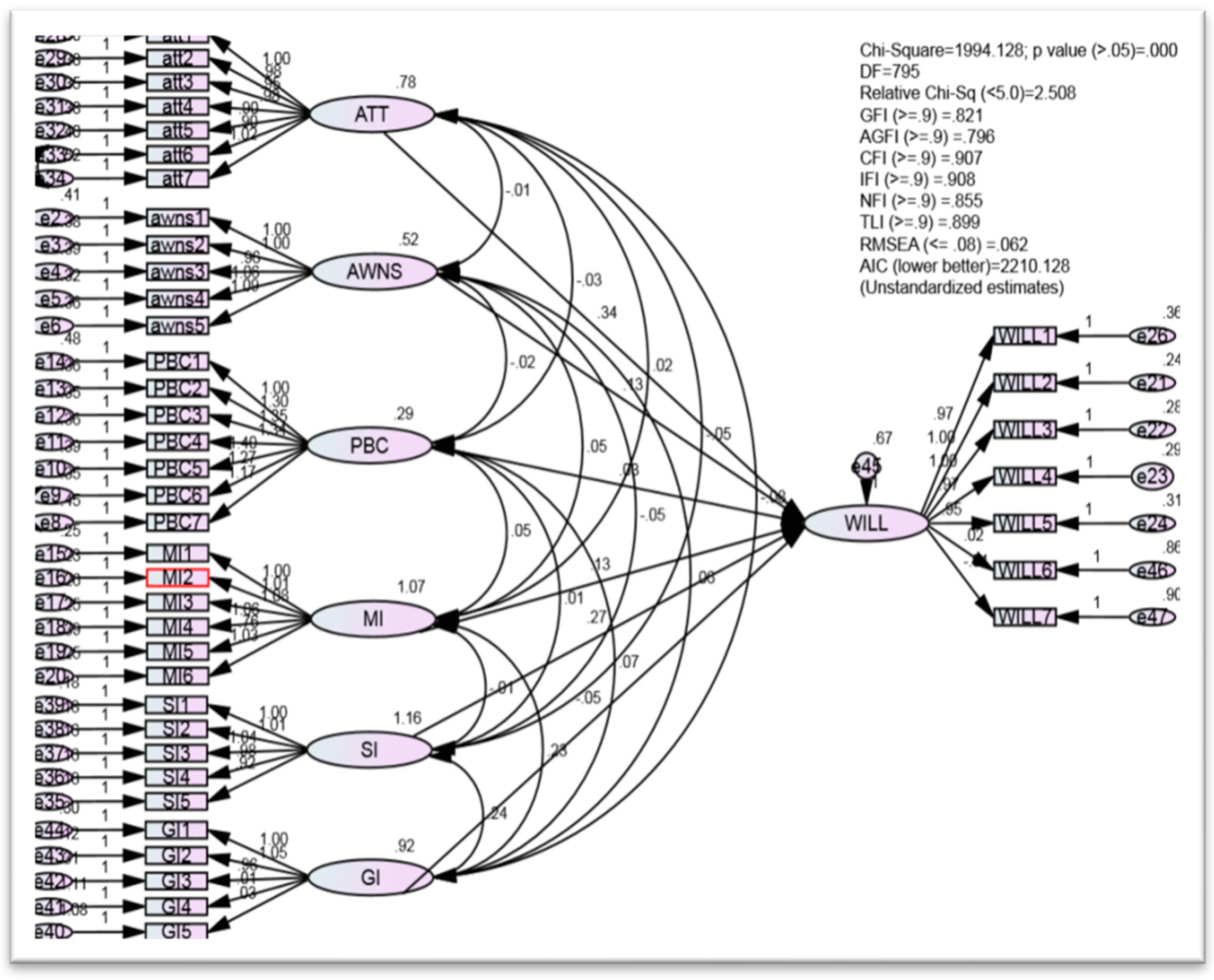

6.4. The Effect of Independent Variables on Households’ Willingness to Sort and Recycle

7. Conclusions

- ⮚

- To redevelop the profile of recyclers and non-recyclers, an expanded theory of planned behavior (TPB) should be adopted, which facilitates the identification of how to sort and recycle extensively;

- ⮚

- Different locations of solid waste generation should be determined in all cities in the country to determine how to evaluate the factors that affect the generation of waste using the application of the geographic information system (GIS). Moreover, the psychological factors affecting behavioral intention and the desire to participate in the sorting and recycling processes should be evaluated in all groups of the community;

- ⮚

- The extent of the importance of the role of children in separating the source of solid waste for the practice of recycling at the family level should be highlighted;

- ⮚

- The performance of services which are provided by governments in the collection and disposal of municipal solid waste in safe ways should be evaluated;

- ⮚

- Competition in private sectors should be improved and encouraged, as they are keen to increase competition among the residents of the city of Dammam and work to raise the standard of living among members of the community;

- ⮚

- Recycling programs should be developed for the residents of Dammam City at different levels of income because such programs are useful in raising the level of awareness among citizens and work to implement approved programs for how to benefit from sorting and recycling of solid waste;

- ⮚

- The role of public awareness and education programs should be examined and developed to improve the knowledge of waste management operators and supervisors;

- ⮚

- The training of sustainable waste handling practices in Dammam for different income levels should be developed.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Wei, J.; Wang, C. An empirical study of consumers’ intention to use ride-sharing services: Using an extended technology acceptance model. Transportation 2020, 47, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, S. Domestic Solid Waste Generation—A Case Study of Semi-Urban Area of Kathua District, Jammu, J & K, India. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2013, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Okalebo, S.E.; Opata, G.P.; Mwasi, B.N. An analysis of the household solid waste generation patterns and prevailing management practices in Eldoret town, Kenya. Int. J. Agric. Policy Res. 2014, 2, 76–89. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, S. Municipal Wastes in Saudi Arabia. Bio-Energy Consult 2020. Available online: https://www.bioenergyconsult.com/municipal-wastes-in-saudi-arabia/ (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- UNEP. Overview of Solid Waste Management in Kenya. 2006. Available online: http://www.unep.org/PDF/Kenya_waste_mngnt_sector/chapter3.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Ouda, O.K.; Cekirge, H.M.; Raza, S.A. An assessment of the potential contribution from waste-to-energy facilities to electricity demand in Saudi Arabia. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 75, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, S. Solid Waste Management in Saudi Arabia; Eco MENA: Doha, Qatar, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul-Aziz, H.M.; Isa, O.; Kadir, N.; Nordin, W.; Daud, A.; Alsebaei, A.; Abu-Rizaiza, A. Study of Baseline Data Regarding Solid Waste Management in the Holy City of Makkah during Hajj 1427. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324731505_Study_of_baseline_data_regarding_solid_waste_management_in_the_holy_city_of_Makkah_during_Hajj_1427 (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Sharma, B.K.; Moser, B.R.; Vermillion, K.E.; Doll, K.M.; Rajagopalan, N. Production, characterization, and fuel properties of alternative. Fuel Process. Technol. 2014, 144, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, P.; Ahmade, K. Impact of solid waste health and the environment. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Green Econ. 2009, 2, 165–168. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Wabel, M.; Al Yehya, W.; Al-Farraj, A.; El-Maghraby, S. Characteristics of landfill leachates and bio-solids of municipal solid waste (MSW) in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2011, 10, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.S.; Kaneesamkandi, Z. Biodegradable waste to biogas: Renewable energy option for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Innov. Appl. Stud. 2013, 4, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M.; Breivik, K.; Syed, J.H.; Malik, R.N.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Jones, K.C. Emerging issue of e-waste in Pakistan A review of status, research needs, and data gap. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 207, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, S.A.; Ch, M.N. Municipal solid waste management in Lahore City District, Pakistan. Waste Manag. 2009, 6, 1971–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabegu, A.B. An Analysis of Municipal Solid Waste in Kano Metropolis, Nigeria. J. Hum. Ecol. 2010, 31, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Zeng, M.; Tague, P.; Zhang, J. Recognizing new activities with limited training data. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Wearable Computers 2017, Maui, HI, USA, 11–15 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Okot-Okumu, J. SSolid Waste Management in African Cities—East Africa. In Waste Management—An Integrated Vision; IntechOpen: Kampala, Uganda, 2012; ISBN 978-953-51-0795-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, L.K.; Field, J.R.; Adkins, E.M.; Parnas, M.L.; Vaughan, R.A.; Zou, M.-F.; Newman, A.H.; Blakely, R.D. Tyr-95 and Ile-172 in Transmembrane Segments 1 and 3 of Human Serotonin Transporters Interact to Establish High Affinity Recognition of Antidepressants. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 2012–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Yu, A. The role of perceived effectiveness of policy measures in predicting recycling behaviour in Hong Kong. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 83, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, D.; Wang, X. Determinants of residents-waste recycling behaviour intentions: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.M.; Khondaker, A. Mitigation measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and enhance carbon capture and storage in Saudi Arabia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 2446–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakpour, A.H.; Zeidi, I.M.; Emamjomeh, M.M.; Asefzadeh, S.; Pearson, H. Household waste behaviors among a community sample in Iran: An application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Yu, A. Key determinants of willingness to support policy measures on recycling: A case study in Hong Kong. Environ. Sci Policy 2015, 54, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukholthaman, P.; Chanvarasuth, P.; Sharp, A. Analysis of waste generation variables and people’s attitudes towards waste management system: A case of Bangkok Thailand. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2017, 19, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurence, H. End-of-life and waste management in life cycle assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2012, 17, 504–510. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.-F.; Tung, P.-J. The Moderating Effect of Perceived Lack of Facilities on Consumers’ Recycling Intentions. Environ. Behav. 2010, 42, 824–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.P.; Zhu, D.; Le, N.P. Factors influencing waste separation intention of residential households in a developing country: Evidence from Hanoi, Vietnam. Habitat Int. 2015, 48, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaizola, I.; Andez, F.S.; Molina, V. Gender issues related to choosing the successor in the family business. Eur. J. Fam. Bus. 2015, 7, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khatib, I.A.; Arafat, H.A. A review of residential solid waste management in the occupied Palestinian Territory: A window for improvement. Sage J. Waste Manag. Res. 2010, 28, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, F.; Asadi, E.; Sadjadi, S.J.; Barzinpour, F. A multi-objective robust optimization model for site-selection and capacity allocation of municipal solid waste facilities: A case study in Tehran. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 816–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wen, Z.-G. Residents’ Household Solid Waste (HSW) Source Separation Activity: A Case Study of Suzhou, China. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6446–6466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajalakshmi, S.; Abbasi, S.A. Solid Waste Management by Composting: State of the Art. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 5, 311–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.M.; Hyde, M.K. The role of self-perceptions in the prediction of household recycling behavior in Australia. Environ. Behav. 2012, 44, 785–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miafodzyeva, S.; Brandt, N. Recycling Behaviour Among Householders: Synthesizing Determinants Via a Meta-analysis. Waste Biomass Valor. 2013, 4, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, M.; Zibarras, L.D.; Stride, C. Using the theory of planned behavior to explore environmental behavioral intentions in the workplace. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilian, B.; Wang, B.; Lewis, K.; Duarte, F.; Ratti, C.; Behdad, S. The future of waste management in smart and sustainable cities: A review and concept paper. Waste Manag. 2018, 81, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrus, G.; Passafaro, P.; Bonnes, M. Emotions, habits and rational choices in ecological behaviours: The case of recycling and use of public transportation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, V.; Coles, R.; Stieger, S.; Pietschnig, J.; Furnham, A.; Rehim, S.; Voracek, M. Conspiracist ideation in Britain and Austria: Evidence of a monological belief system and associations between individual psychological differences and real-world and fictitious conspiracy theories. Br. J. Psychol. 2011, 102, 443–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoleto, A.P.; Kurisu, K.H.; Hanaki, K. Model development for household waste prevention behaviour. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 2195–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.F.; Ngai, E.W.T. A research agenda on managerial intention to green it adoption: From norm activation perspective. In Proceedings of the PACIS 2014, Chengdu, China, 24–28 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Botetzagias, I.; Dima, A.-F.; Malesios, C. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior in the context of recycling: The role of moral norms and of demographic predictors. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 95, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifee, H.; Sajib, M.D.; Hafiz, E. Readymade garment industries going green. Financ. Express 2017, 4, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Miandad, R.; Anjum, M.; Wagas, M. Solid Waste Management in Saudi Arabia. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 1, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Huang, G.; Yin, X.; Gong, Q. Residents’ Waste Separation Behaviors at the Source: Using SEM with the Theory of Planned Behavior in Guangzhou, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 9475–9491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ling, M.; Lu, Y.; Shen, M. External influences on forming residents’ waste separation behaviour: Evidence from households in Hangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2017, 63, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.R.N. An Overview of Conflict; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PE, USA, 2006; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Ghani, W.A.W.A.K.; Rusli, I.F.; Biak, D.R.A.; Idris, A. An application of the theory of planned behaviour to study the influencing factors of participation in source separation of food waste. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 1276–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Sultana, A.; Rasheduzzaman, M.; Kundu, G.K.; Kamal, A.K.I.; Uddin, M.K. Uddin, Assessment of the Present State and Economical Prospects of Solid Waste at Amin Bazar Waste Dumping Site, Dhaka, Bangladesh. J. Sci. Res. 2015, 7, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.S.; Ho, Y.M.; Manaf, L.A.; Sharaai, A.H.; Nabegu, A.B. Income Perspective on the Factors Influencing Households’ Recycling Intention: Implications from the Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour. J. Malays. Inst. Plan. 2019, 2, 191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, D.C. Statistics for the Behavioural Sciences, 7th ed.; Cengage Learning Products: Belmont, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aron, A. Online Dating: The Current Status—And Beyond. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2012, 13, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, R.; Dear, B.; Li, G.; Virgona, J.; Conyers, M.; Hackney, B.; Tidd, J. Perennial pastures for recharge control in temperate drought-prone environments. Part 1: Productivity, persistence and herbage quality of key species. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 2010, 53, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.; Bashyal, S.; Bachman, B. Demographic impacts on environmentally friendly purchase behaviors. J. Target. Meas. Anal. Mark. 2012, 20, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. The influence of attitudes on behavior. In The Handbook of Attitudes; Albarracin, D., Johnson, B.T., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 173–221. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, R.; Liebe, U. Are the affluent prepared to pay for the planet? Explaining willingness to pay for public and quasi-private environmental goods in Switzerland. Popul. Environ. 2010, 32, 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainudin, M.M.; Afthanorhan, A.; Mohammed, M. Comparison Between CB-SEM and PLS-SEM: Testing and Confirming the Maqasid Syariah Quality of Life Measurement Model. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2019, 3, 608–614. [Google Scholar]

- Hornik, J.; Joseph, C.; Mandansky, M.; Narayana, C. Determinant of recycling behavior: A synthesis of research result. J. Socio. Econ 2005, 24, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeva, K.; Alriksson, S. Influence of recycling programmes on waste separation behaviour. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd’razack, N.T.; Medayese, S.; Shaibu, S.; Adeleye, B. Habits and benefits of recycling solid waste among households in Kaduna, North West Nigeria. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 28, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Jensen, J.H.; Jensen, M.H.; Kulikovskaja, V. Consumer behaviour towards price-reduced suboptimal foods in the supermarket and the relation to food waste in households. Appetite 2017, 116, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegaray, F.; Hansstein, F.V. Assessing the intention-behavior gap in electronic waste recycling: The case of Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akil, A.M.; Foziah, J.; Ho, C.S. The effects of socio-economic influences on households recycling behaviour in Iskandar Malaysia. Proc. Soc. Behav. 2015, 202, 124–134. [Google Scholar]

| City | Population (2010) | Total Collected Volume per Day m3/day | Total Refuse Volume m3/day | Waste Generation Kg/Capita/Day |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dammam | 159,400 | 2750 | 326,150 | 2.04 |

| Alkhobar | 100,200 | 1363 | 161,652 | 1.61 |

| Dhahran | 25,000 | 573 | 67,958 | 2.72 |

| Rahima | 42,200 | 835 | 99,031 | 2.35 |

| Abaqaiq | 45,727 | 785 | 93,101 | 2.04 |

| Regions of Dammam | Socio-Economic Levels of Dammam in Each District | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HL | ML | LL | Total | |

| West of Dammam | 4 | 9 | 6 | 19 |

| Middle of Dammam | 6 | 14 | 8 | 28 |

| East of Dammam | 12 | 8 | 8 | 28 |

| Total | 22 | 31 | 22 | 75 |

| Income Levels | Population Region | No. of Respondent | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Level | 310,000 | 175 | 39 |

| Middle Level | 320,000 | 180 | 40 |

| Low Level | 170,000 | 95 | 21 |

| Total | 800,000 | 450 | 100 |

| No. | Factors |

|---|---|

| Psychological Factors (internal Factors) | |

| 1 | Attitude |

| 2 | Awareness |

| 3 | Perceived Behavior Control |

| External Factors | |

| 1 | Social Influences |

| 2 | Market Incentives |

| 3 | Government Facilitators |

| Willingness toward Sorting and Recycling | Significance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | Awareness | Perceived Behavioral Control | Social Influence | Market Incentive | Government Facilitators | ||

| Low Income | Middle Income | 0.935 | 0.252 | 0.042 | 0.486 | 0.718 | 0.541 |

| High Income | 0.357 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.096 | 0.57 | 0.146 | |

| Middle Income | Low Income | 0.935 | 0.252 | 0.042 | 0.486 | 0.718 | 0.541 |

| High Income | 0.169 | 0.001 | 0.181 | 0.132 | 0.731 | 0.008 | |

| High Income | Low Income | 0.357 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.096 | 0.57 | 0.146 |

| Middle | 0.169 | 0.001 | 0.181 | 0.132 | 0.731 | 0.008 | |

| Multiple Comparisons | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables—Willingness to Sort and Recycle | |||||||

| Willingness to Sort and Recycle | Mean Difference | Std. Error | Sig | 95% Confidence Interval | |||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| Scheff | High Income | Low Income | −32.4355 | 3.1450 | 0.00 | −40.1601 | −24.7108 |

| Middle Income | −5.8316 | 3.4470 | 0.24 | −14.2981 | 2.6340 | ||

| Middle Income | High Income | 32.4350 | 3.1450 | 0.00 | 24.7100 | 40.1600 | |

| Low Income | 26.6020 | 3.7493 | 0.00 | 17.3940 | 35.8120 | ||

| Low Income | Middle Income | 5.8310 | 3.4470 | 0.24 | −2.6348 | 14.2980 | |

| High Income | −26.6038 | 3.7493 | 0.00 | −35.8128 | −17.3949 | ||

| Bonferroni | High Income | Low Income | −32.4355 | 3.1450 | 0.00 | −39.9937 | −24.8773 |

| Middle Income | −5.8316 | 3.4470 | 0.27 | −14.1157 | 2.4520 | ||

| Middle Income | High Income | 32.4350 | 3.1450 | 0.00 | 24.8773 | 39.9930 | |

| Low Income | 26.6030 | 3.7493 | 0.00 | 17.5930 | 35.6140 | ||

| Low Income | Middle Income | 5.8310 | 3.4470 | 0.27 | −2.4524 | 14.1150 | |

| High Income | −26.6038 | 3.7493 | 0.00 | −35.6144 | −17.5933 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Labib, O.A.; Abd Manaf, L.B.; Bin Sharaai, A.H.; Zaid, S.S.B.M.; Khalil, M.S. The influence of Socio-Psychological Factors on Residents’ Willingness to Practice Sustainable Waste Handling in Dammam City, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13654. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813654

Labib OA, Abd Manaf LB, Bin Sharaai AH, Zaid SSBM, Khalil MS. The influence of Socio-Psychological Factors on Residents’ Willingness to Practice Sustainable Waste Handling in Dammam City, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability. 2023; 15(18):13654. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813654

Chicago/Turabian StyleLabib, Ossama Ahmed, Latifah Binti Abd Manaf, Amir Hamzah Bin Sharaai, Siti Sarah Binti Mohamad Zaid, and Muhammed Salisu Khalil. 2023. "The influence of Socio-Psychological Factors on Residents’ Willingness to Practice Sustainable Waste Handling in Dammam City, Saudi Arabia" Sustainability 15, no. 18: 13654. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813654

APA StyleLabib, O. A., Abd Manaf, L. B., Bin Sharaai, A. H., Zaid, S. S. B. M., & Khalil, M. S. (2023). The influence of Socio-Psychological Factors on Residents’ Willingness to Practice Sustainable Waste Handling in Dammam City, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 15(18), 13654. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813654