Abstract

Focusing on the moral hazard of third-party environmental service providers in monitoring and controlling the emission of pollutants by enterprises, this paper takes the third-party governance of environmental pollution under the incentive-and-constraint mechanism as its research object. It also constructs a game model involving emission-producing enterprises producing emissions, third-party environmental service providers, and local governments. Adopting this evolutionary game model, this paper analyzes the mechanism of local government’s role in effectively resolving the moral hazard between emission-producing enterprises producing emissions and third-party environmental service providers by exploring the conditions of spontaneous cooperation between emission-producing enterprises producing emissions and third-party environmental service providers. This paper provides a possible solution to the problem of emission-producing enterprises or third-party environmental service providers stealing and leaking emissions, as well as collusion between the two. The study presents two major findings. (1) There are three possible scenarios of breach of contract: unilateral breach by third-party environmental service providers, unilateral breach by emissions-producing enterprises, and collusion between the two. When a third-party environmental service provider unilaterally breaches a contract, emission-producing enterprises have regulatory responsibilities toward them. In such cases, local governments should reduce the penalties imposed on emission-producing enterprises. This measure would decrease the willingness of these enterprises to allocate a higher proportion of collusion payments to third-party environmental service providers. However, it would simultaneously provide a new avenue through which third-party environmental service providers would gain benefits, thereby increasing their expected gains from collusion. This would create a new game between the two parties, leading to the failure of collusion negotiations. (2) The efficacy of incentive-constraint mechanisms is influenced by the severity of contractual breaches, represented by the magnitude of stealing and leaking emissions. When false emissions reduction is at a high level, increasing the incentives for emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers cannot effectively prevent collusion; when the level is moderate, incentives for third-party environmental service providers can effectively prevent collusion, but incentives for emission-producing enterprises cannot; when the level is low, increasing the incentives for emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers can help prevent collusion. (3) When emission-producing enterprises engage in unilateral discharge, if a local government’s incentive for third-party environmental service providers exceeds the benefits it can obtain from regulating the discharged amount, third-party environmental service providers tacitly approve the company’s discharge behavior. However, with the strengthening of local government regulations, emission-producing enterprises tend to engage in more clandestine discharging of pollutants to obtain greater rewards. This practice infringes upon the revenue of third-party environmental service providers, as their earnings are positively correlated with the amount of pollution abated. Third-party environmental service providers no longer acquiesce to corporate emissions theft, resulting in an increase in the probability of the detection of emission-producing enterprises’ illicit discharges; in this way, the behavior of these enterprises is regulated.

1. Introduction

Corporate emissions are still a pressing environmental problem in China’s ecological development. The high cost and low efficiency of pollution control make it difficult for a large number of emission-producing enterprises to meet national emission-control standards while ensuring their profits. At the same time, the Chinese government has gradually shifted from being the main party responsible environmental pollution treatments to being the supervisor, which has facilitated the development of an environmental governance model based on market mechanisms. The Opinions on Promoting Third-Party Environmental Pollution Governance issued by the General Office of the State Council in 2015 strongly promoted “third-party environmental pollution governance” in environmental management. According to the free-market-transaction mechanism, third-party environmental service providers have reduced the cost and improved the efficiency of pollution treatment [1,2]. Third-party governance has undoubtedly freed many emission-producing enterprises that do not have the capacity to govern pollution from the predicament of easy production and difficult governance. In addition, third-party pollution control has the advantage of clustering, which reduces the cost of pollution control and saves resources for the whole of society.

The model of third-party environmental-pollution governance has been applied in developed countries in ways that are relevant to China, but China’s environmental governance system is complex, and the relationship between emission-producing enterprises, third-party environmental service providers, and the government within China’s environmental management system, as well as the specific implementation methods of government policies, are unique. Therefore, although the third-party environmental pollution governance model has received positive feedback from the Chinese market, there are still many risks in the process of governance. China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment has pointed out that in recent years, a few third-party environmental service providers have been blindly pursuing economic interests, making false claims, and helping emission-producing enterprises to pass, seriously disrupting the third-party environmental service market order. On 27 February 2023, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment announced three typical cases of falsification by third-party environmental service providers, while the Ministry of Ecology and Environment requested that ecological and environmental departments at all levels continue to increase the supervision of third-party environmental service providers, as well as working with relevant departments to seriously investigate and deal with violations of the law and crack down on criminals. However, as builders of pluralistic governance systems and as the supervisors of environmental governance, local governments’ use of the strengthening of law enforcement alone to restrain of third-party environmental service providers and emission-producing enterprises is not ideal. In addition to this, it is necessary to establish and improve local pollutant-emission-control standards and ecological-protection-compensation mechanisms, as well as implementing existing tax incentives to promote environmental protection and policies aimed at incentivizing the prevention of pollution [3]. Therefore, there is a need to further study the game of interests and interaction mechanisms between third-party environmental service providers and emission-producing enterprises under the supervision of local governments.

At present, the research on the third-party governance of environmental pollution includes three main areas. The first is the definition of the meaning and value of third-party governance [4,5], the legislative improvement or adaptive interpretation of the current system [6], and the deep institutional logic of third-party-governance contractual relationships and their generation [7], among others. The second is the study of the relevant factors affecting third-party governance and their policy effects [8,9,10]. It was found that direct performance, process-management effectiveness, and stakeholder satisfaction with cooperation all influence the decision making of third-party environmental service providers [11,12], and that pollution taxes and incentivization policies positively affect pollution governance [13,14,15,16]. The third encompasses the barriers and dilemmas of third-party environmental-service-provider governance, which were explored by constructing theoretical models. Studies have constructed tripartite game models among enterprises, local governments, and the central government [17,18,19,20,21], or among enterprises, governments, and the public [22,23], and explored the mechanisms of the role of relevant factors in tripartite decision making. Although theoretical analyses were performed based on descriptive studies, and the factors influencing the governance of third-party environmental service providers were identified through empirical studies, the mechanisms of action and the perspectives for the optimization of relevant factors in the relationship between third-party environmental service providers and emission-producing enterprises are unclear. In addition, most previous studies constructed models of government–enterprise collusion, such as rent-seeking and rent-setting by the government and bribery by emission-producing enterprises, in addition to the lack collusion between emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers, stopping at the game between emission-producing enterprises or third-party environmental service providers and the government [24,25], without examining the game between emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers.

There are many moral hazards involved in the process of corporate emission management, and each participant makes dynamic choices based on environmental regulations and economic status. Based on the premise of the limited rationality of the participating actors [26], and sorting out the conditions under which each equilibrium solution is established, the evolutionary game model provides a reliable method for exploring the mechanism of the government’s role in risk mitigation in different situations. Previous studies constructed game models of decentralized and centralized decision-making between emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers, or built a two-party game between the government and third-party environmental service providers, and between the government and emission-producing enterprises, to explore the reasons for opportunistic behaviors and government incentives for third-party environmental service providers and enterprises by comparing the effects of different government-subsidy methods. On one hand, the decision-making processes of emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers are dynamically related. This research method of separating the decentralized and centralized decision-making of emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers cannot be used to further explore the conversion mechanism in decision making and the reasons for the opportunistic behaviors of both parties, and it cannot be used to mitigate the key risks from the perspective of the internal game of sewage discharge and sewage-treatment subjects; thus, it cannot be used to explore the boundary conditions of spontaneous cooperation between the two parties. The incentive-and-constraint policy, although able to guide the decision making of the enterprises in the short term, cannot completely curb the abnormal strategies of enterprises, and with the emergence of opportunistic behavior, the guiding effect is weakened. Policies need to change dynamically to be effective, yet their lagging nature makes it difficult to achieve this goal. Therefore, thinking about how to switch from incentive and constraint mechanisms to market mechanisms is an effective means of mitigating risks. On the other hand, in the studies related to the game between the government and emission-producing enterprises, and between the government and third-party environmental service providers, it is only concluded that subsidies increase the efforts of pollutant-control parties. In addition, the studies consider how the treatment of pollutants can be changed from passive to active from the perspective of the attribution of rights and responsibilities. This approach, which separates emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers, also fails to fundamentally address the risk of collusion and ignores the decision-making linkages and dynamics between the two parties.

Compared with previous studies, this paper constructs an evolutionary game model involving local governments, emission-producing enterprises, and third-party environmental service providers, focusing on the internal game between emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers, to analyze the intrinsic mechanism of compliance or default by emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers under different regulatory restrictions and the reasons why it is difficult for the system to form an equilibrium. The conditions under which the government’s incentive-and-constraint mechanism can work effectively in the context of dynamic decision-making and the transition conditions under which emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers can switch from passive to active pollution control are established. Next, we explore how local governments should guide the behavior of each party to achieve the equilibrium of the system. This provides not only a reference for quantitative research on the governance of third-party environmental service providers, but also possible solutions to the problem of emissions evasion and leakage by emission-producing enterprises or third-party environmental service providers, as well as collusion problems between emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers.

2. Problem Description

Enterprise-emissions governance mainly involves three main parties: the government, emission-producing enterprises, and third-party environmental service providers. Third-party environmental pollution governance is a mode in which the discharger commissions a third-party environmental service provider to carry out pollution management by paying or contractually agreeing to pay for it. Emission-producing enterprises entrust third-party environmental service providers to act as agents for the construction and maintenance of enterprises’ environmental protection facilities and the specialized treatment of pollutants, which reduces the pressure on the enterprises’ to treat pollution and also allows the scale and intensification of the pollution treatment work [27,28]. However, there are some possible moral hazards in the third-party-governance model.

First, the pursuit of economic benefits by emission-producing enterprises leads them to reduce the cost of pollution control by stealing emissions, which not only reduces the cost of pollution control paid to third-party environmental service providers but also increases the performance-related incentives provided by the government to reduce emissions.

Second, third-party environmental service providers have falsified test reports, replaced test samples, and undertaken other fraudulent governance practices without paying the cost of pollution control, thereby obtaining the proceeds of pollution control paid for by emission-producing enterprises, and even those provided by local governments in the form of incentives to reduce emissions.

Furthermore, there is a risk of collusion between emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers to violate emissions limits. Both enterprises and third-party environmental service providers are motivated by irregularities and fraudulent treatment, and both parties sign duplicate contracts to maximize revenue. On one hand, emission-producing enterprise, as the direct beneficiaries, have the right to take the initiative. On the other hand, false emission-certification reports not only reduce emission-producing enterprises’ pollution-control expenses but also reduce the environmental tax they need to pay and allow them to obtain additional incentives to reduce emissions. Therefore, to maintain their relationships, emission-producing enterprises need to give financial compensation to third-party environmental service providers to achieve the increase in their respective benefits from their agreements.

Finally, local governments are assessed by local economic performance, but there is a lag in the economic effects of the various costs of environmental control inputs, which leads to the inactive local government supervision of local environmental protection, the inadequate adjustment of system improvements, false government enforcement authorities, and insufficient enforcement, exacerbating the risk of collusion between emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers.

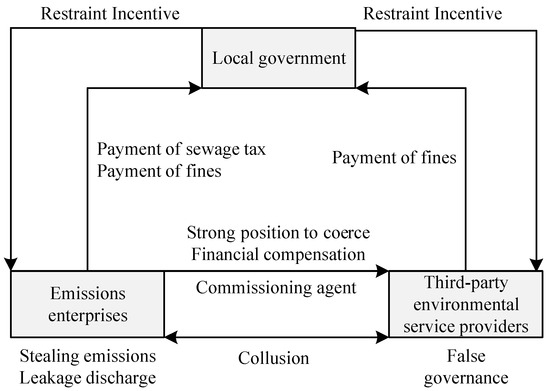

The key subjects and main processes involved in the process are shown in Figure 1. As shown in the figure, in the process of entrusting pollution to a third-party environmental service provider, the emission-producing enterprise chooses to deliver pollutants directly, as specified, or to steal a portion of the discharge and then deliver it. After receiving the pollution delivered by the enterprise, the third-party environmental service agency chooses to treat it according to the regulations or to falsely treat it; in the latter case, the emission-producing enterprise entrusts the business to a third-party environmental service provider that does not have the disposal capacity or requisite qualifications, hampering emissions reduction, for which the enterprise should bear financial responsibility. In addition, this paper contends that there is collusion between the emission-producing enterprise and the third-party environmental service provider when both are at fault, i.e., in which the emission-producing enterprise gives financial compensation to the third-party environmental service provider and then directly steals emissions, and the third-party environmental service provider helps the emission-producing enterprise to issue false reports. Local governments have both strong and weak regulations in the pollution-control process involving third-party environmental service providers. Under strong regulatory conditions, local governments collect emissions taxes from emission-producing enterprises and also impose penalties for non-compliance or offer incentives for excess emissions reductions.

Figure 1.

Third-party environmental service providers and their processes for the treatment of the main sources of pollution.

3. Model Construction

3.1. Basic Assumptions

In this paper, we contend that emission-producing enterprises, to evade the supervision of local governments, emit emissions that do not meet the national standard emission concentrations and exceed the maximum emissions limits through illegal means, such as the following: setting up hidden discharge pipes, in order to steal and conceal emissions; the issuing of false reports by third-party environmental service providers not truly treating pollution; situations in which emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers are both in breach of contract, i.e., emission-producing enterprises give financial compensation to third-party environmental service providers and then directly steal emissions, and third-party environmental service providers help emission-producing enterprises to issue false reports.

(1) When an emission-producing enterprise entrusts the treatment of pollutants to a third-party environmental service provider, the emission-producing enterprise has the motive of stealing emissions (direct emissions and non-compliant emissions without entrusting their treatment to a service provider), while the economic benefits for the third-party environmental service provider are provided by the emission-producing enterprise; the service provider therefore fails to effectively regulate the emission-producing enterprise, and may even collude with emission-producing enterprise. Assume that the probability of a pollutant being treated following the law is , and the probability of the existence of an illegal discharge or collusion with a third-party environmental service provider is . The main business income does not affect the model analysis in this paper, so, for the sake of simplifying the model, it is not considered here. It is assumed that the emission volume of the emission-producing enterprise is , the unit cost entrusted to the third-party environmental service provider is , the unit-treatment cost of the third-party environmental service provider is , and the emission volume after treatment is . The unit emission fee paid by the polluting enterprise according to the national standard is . Therefore, under normal circumstances, the cost of pollution control is and the revenue of the third-party environmental service provider is . If there is emission-stealing behavior by the emission-producing enterprise, the amount of stolen emissions is , and the amount of emissions after stealing is . At this time, the amount of emissions after treatment by the third-party environmental service provider is , . When an emission-producing enterprise colludes with a third-party environmental service provider, both parties agree that the volume of emissions to be publicly announced is , and the collusion proceeds allocated by the enterprise to the third-party environmental service provider are . Without considering government incentives and other violations, is greater than the proceeds when the third-party environmental service provider treats the emissions volume and less than the cost paid by the emission-producing enterprise for treatment compliance and its corresponding taxes, i.e., . The revenue of the discharging enterprise is related to the volume of emissions [29,30], and in general, the revenue of the discharging enterprise satisfies the equation , where is the coefficient, although this term is canceled out in the process of solving the replication dynamic equation based on the model, so it is not considered in this paper, for the sake of simplifying the model.

(2) Third-party environmental service providers act between the government and enterprises, both to monitor emissions and emissions reports and to help enterprises to carry out professional pollution control. However, there is potential for falsifications by third-party environmental service providers. On one hand, although the government has strict qualification requirements for third-party environmental service providers, the some third-party environmental service providers fail to meet the government’s waste-disposal standards by delivering emissions to emission-producing enterprises, allowing them to steal emissions. Furthermore, emission-producing enterprises entrust the disposal of emissions to third parties that do not have sufficient disposal capacity or the requisite qualifications, which is a form of inaction in terms of emissions reduction, for which enterprises should bear responsibility. Suppose such behavior is discovered by the local government, and the emission-producing enterprise must pay a fine and, similarly, the third-party environmental service provider must pay a fine ; the third-party environmental service provider may conspire with the emission-producing enterprise to produce false pollution-control reports to help the emission-producing enterprise reduce its environmental costs, helping to conceal the emissions-related behaviors of illegal enterprises. In this paper, we assume that the third-party environmental service provider treats the discharge and produces a discharge report for the emission-producing enterprise, and there is potential for either unilateral false treatment or collusion with emission-producing enterprises. This is assumed to have a probability of , and the probability of honest treatment and the issuing of a monitoring report based on the actual situation is . If the third-party environmental service provider’s unit cost for pollution control is , it can obtain the proceeds of pollution control paid by the emission-producing enterprise, or obtain the proceeds of collusion when it colludes with the emission-producing enterprise . When the enterprise fulfills the contract, the third-party environmental service provider may be driven by unilateral interests to issue false reports.

(3) Local governments, as the external supervisors of environmental pollution management, regulate the emissions-theft behavior of emission-producing enterprises, the falsification behavior of third-party environmental service providers, and the collusion between the two parties. Strict restrictions on regulating the discharge behavior of regulated enterprises increase the administrative costs of local governments and reduce their administrative performance while increasing the development costs of enterprises and hindering local economic development. The incentivization funds under strictly controlled conditions incur opportunity cost, which is a potential loss concerning the government, assuming that the loss is . Assume that the probability of strong local government control is and that the probability of weak control is . The probabilities of the detection of a unilateral violation by an emission-producing enterprise or a third-party environmental service provider under strong and weak government control are and , respectively, and . As the third-party environmental service providers are jointly and individually liable for violations, in addition, emissions thefts by enterprises can also create profit losses for third-party environmental service providers, and the two regulate each other’s daily business. The specific mechanism of action is analyzed in detail in Section 4. The probabilities of the detection of collusion between emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers under strong and weak government regulation are and , respectively, and . Collusion in the falsification of emissions tends to be more difficult to detect, so there is and . The maximum amount of discharge of an enterprise specified under command-based environmental regulation is . Assume that the fines resulting from the concealment and leakage of emissions by emission-producing enterprises are , is a function related to the amount of stolen emissions , and ; the fines obtained by the third-party environmental service providers when they are discovered to be falsifying treatments are , ; and the fines obtained by the emission-producing enterprises and the third-party environmental service providers when they are discovered to be colluding are , , where is the fine for the emission-producing enterprise and is the fine for the third-party environmental service provider. Under strong regulation, the unit rewards and penalties arranged by the government for the treatment results of the third-party environmental service providers is , the unit rewards and penalties arranged by the government for emission-producing enterprises is , and the unit price of the total expenditure of the rewards and penalties is .

3.2. Construction of the Game Matrix

The moral hazard between enterprises and third-party environmental service providers is an important obstacle in the process of ecological construction. The moral hazards of emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers include the risk of unilateral violation and the risk of collusion. The game between emission-producing enterprises, third-party environmental service providers, and local governments has eight possible outcomes. The first to third rows of each element in the benefits matrix represent the benefits of emission-producing enterprises, third-party environmental service providers, and local governments in turn, and their benefit matrices are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Benefit matrix for emission-producing enterprises, third-party environmental service providers, and local governments.

① When the decisions of emission-producing enterprises, third-party environmental service providers, and local governments are compliance, governance, and strong control, emission-producing enterprises pay pollution-treatment costs and emission fees according to the national regulation standard, receive government pollution-treatment incentives , and pay a penalty if . The third-party environmental service providers receive pollution-treatment benefits and local government incentives and pay pollution-treatment costs . The net benefits for the emission-producing enterprise and the third-party environmental service provider are and , respectively. The local government gains environmental benefits , collects emission fees , provides the incentive for third-party environmental service providers and emission-producing agencies, and incurs an opportunity cost while strictly restraining and regulating the emission behaviors of enterprises. At this point, the net benefit for the local government is .

② When the decisions of emission-producing enterprises, third-party environmental service providers, and local governments are compliance, false governance, and strong control, emission-producing enterprises pay pollution-treatment costs and emission fees according to the national regulation standard, receive government pollution-treatment incentives , and pay fines when third-party environmental service providers are found to be governing falsely. Third-party environmental service providers can obtain pollution-control benefits and local government incentives , and receive fines with a probability of when false treatments are detected. The net benefits for the emission-producing enterprise and the third-party environmental service provider are and , respectively. The local government obtains environmental benefits , collects emission fees , provides the incentives to third-party environmental service providers and emission agencies, and collects fines , with a probability P of detecting false governance by third-party environmental service providers, and incurs an opportunity cost while strictly restraining and regulating enterprises’ emission behaviors. At this point, the local government’s net benefit is .

③ When the decisions of emission-producing enterprises, third-party environmental service providers, and local governments are compliance, governance, and weak control, emission-producing enterprises pay pollution-control costs and emission fees according to the national regulation standard. Third-party environmental service providers can obtain pollution-control benefits and pay pollution-control costs . The net benefits for emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers are and ). The local government receives environmental benefits and collects emissions fees . At this point, the net benefit for the local government is .

④ When the decisions of the emission-producing enterprises, the third-party environmental service providers, and the local government are compliance, false governance, and weak control, the emission-producing enterprises pay the cost of pollution treatment , the emission fee according to the national regulation standard, and fines when the third-party environmental service providers are found to engage in false governance. Third-party environmental service providers can obtain the proceeds from pollution treatment , and with a probability of of receiving fines for false treatments. The net benefits for the polluters and the third-party environmental service providers are and , respectively. The local government receives environmental benefits , collects emissions fees , and issues fines , with a probability of detecting false treatments by third-party environmental service providers. The net benefits for the local government at this point are .

⑤ When the decisions of emission-producing enterprises, third-party environmental service providers, and local governments are non-compliance, governance, and strong control, emission-producing enterprises pay pollution-treatment costs and emission fees according to the national regulation standard, receive government pollution-treatment incentives , and receive fines with a probability of being found to be in violation. Third-party environmental service providers can receive pollution-treatment benefits and local government incentives , and pay pollution control costs . The net benefits for the emitter and the third-party environmental service provider are and , respectively. The local government obtains environmental benefits , collects emissions fees , provides the incentive for third-party environmental service providers and emission-producing agencies, discovers that the emission-producing enterprises violate the law with a probability of and collects fines , and incurs opportunity costs while strictly restraining and regulating the enterprises’ emission behavior. At this point, the net benefits for the local government are .

⑥ When the decisions of emission-producing enterprises, third-party environmental service providers, and local governments are non-compliance, false governance, and strong regulation, there is collusion between emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers. The polluting firm cedes profits to the third-party environmental service provider, pays an emission fee according to the national regulation standard, receives a government incentive for pollution control, and is fined for non-compliance with probability of . Third-party environmental service providers can earn collusion-related profits π and local government incentives , and receive fines for false governance with a probability of . The net benefits for the emission-producing enterprises and the third-party environmental service providers are and , respectively. The local government obtains environmental benefits , collects emissions fees , provides the incentive for the third-party environmental service providers and the emission-producing agencies, discovers that the emission-producing enterprises collude with the third-party environmental service providers and administers fines with probability of , and incurs an opportunity cost while strictly restraining the emission behaviors of the regulated enterprises. At this point, the net benefit for the local government is .

⑦ When the decisions of the three parties, namely, the emission-producing enterprise, the third-party environmental service provider, and the local government, are non-compliance, governance, and weak control, the emission-producing enterprise pays the treatment cost and the emission fee according to the national regulation standard, and receives a fine for violation with a probability of . The third-party environmental service providers obtains the pollution-treatment benefit and pay the pollution-treatment cost . The net benefits for the emission-producing enterprises and the third-party environmental service providers are and , respectively. The local government receives environmental benefits , collects an emission fee , and collects a fine for violation by the emission-producing enterprise with a probability of . At this point, the net benefit for the local government is .

⑧ There is collusion between emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers when the decisions of the three parties are non-compliance, false governance, and weak control. The emission-producing enterprise concedes profits to the third-party environmental service provider, pays the emission fee according to the national regulation standard, and is fined for violation with a probability of . Third-party environmental service providers can earn collusion-related profits and are fined for false governance with a probability of . The net benefits for the emission-producing enterprise and the third-party environmental service provider are and , respectively. The local government obtains environmental benefits , collects the emission fee , and fines the emission-producing enterprise and the third-party environmental service provider for collusion with a probability of . At this point, the net benefits for the local government are .

3.3. Solution and Discrimination of Equilibrium Point

(1) Replication dynamic equation of the emission-producing enterprise

Table 1 presents the expected benefit when an emission-producing enterprise is “compliant” as , the expected benefit when an emission-producing enterprise is “non-compliant” as , and the average benefit as . Specifically:

The revenue function of the polluting firm, when it complies, is

The revenue function in case of default by the emitter is

The average revenue for emission-producing enterprises is

The replicated dynamic differential equation for the polluting firms can be expressed as

(2) Replication of dynamic equations for third-party environmental service providers

Table 1 presents the expected benefit when the third-party environmental service provider engages in “governance” as , the expected benefit when the third-party environmental service provider engages in “false governance” as , and the average benefit as . Specifically:

The revenue function of a third-party environmental service provider, when it complies, is

The revenue function in case of default by the third-party environmental service provider is

The average revenue for third-party environmental service providers is

The replicated dynamic differential equation for third-party environmental service providers can be expressed as

(3) Replication of dynamic equations for local governments

Table 1 presents the expected return of when the local government is in “strong control” and the expected return of when the local government is in “weak control,” with an average return of . Specifically:

The revenue function when the local government complies is

The revenue function in case of local government default is

The average benefit for local governments is

The replicated dynamic differential equation for local government can be expressed as

In summary, the three-dimensional dynamic system consisting of replicated dynamic equations for the strategic choice of the three parties, the emission-producing enterprises, the third-party environmental service providers, and the local government, is as follows:

Let . By solving Equation (13), we can obtain eight pure strategy-equilibrium points , , , , and a set of hybrid strategy points. Since the evolutionarily stable equilibrium is a strict Nash equilibrium (a pure strategy equilibrium), the ESS exists only in the eight pure strategy-equilibrium points, on which a stability discussion can be carried out. The mixed strategy points indicate the complexity and are omitted here.

4. Discussions

According to the Lyapunov stability theory, the method used to discriminate the asymptotic stability of the pure strategy-equilibrium points is carried out by constructing Jacobian matrices, solving the eigenvalues of each pure strategy-equilibrium point in turn, and determining their evolutionary stability according to the sign of the eigenvalues. The Jacobian matrices of the dynamical system established by finding the partial derivatives concerning , , and for , , and , respectively, are

The Jacobian matrix eigenvalues of the eight equilibrium points are expressed by , , and , respectively, and the Jacobian matrix of each equilibrium point is analyzed by Lyapunov’s discriminant method.

When , , , the asymptotic equilibrium point is reached, and the stability types of other local equilibrium points are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Analysis of equilibrium-point-stability judgments.

When the system is in equilibrium, and indicate that the emission-producing enterprises and the third-party environmental service providers honor their contracts to curb pollution and obtain greater benefits than from unilateral default. , i.e., the enterprise treats pollution effectively, below the regulatory requirement, or exceeds it by a small amount, but . However, at this point, government regulation is weak, the probability of the collusion between the emission-producing enterprises and the third-party environmental service providers being discovered is low, , and the two parties collude over time out of interest. The lower means that the emission-producing enterprises and the third-party environmental service providers can obtain more revenue by colluding, so the collusion revenue allocated by the emission-producing enterprises to the third-party environmental service providers is inversely proportional to . In lax regulatory environments, the probability of collusion being detected is not high, increases in collusion draw attention from local governments, and regulation is consequently strengthened, leading to equilibrium, when

It can be observed that when the regulatory intensity of local governments increases ( and increase), it is unclear whether the range of values for increases or decreases. When a third-party environmental service provider unilaterally engages in false governance and the local government imposes a higher fine on an emission-producing enterprise, Equation (15) is more likely to hold. In this case, the adjustable range of and the maximum upper limit of collusion increase, widening the scope for emission-producing enterprises to benefit from collusion. Moreover, when not colluding, emission-producing enterprises not only face increased regulatory costs but also bear the risk of hefty fines in the event of third-party environmental service providers’ breach of contract. The emission-producing enterprises are more willing to choose collusion after weighing its advantages and disadvantages. In addition, the incentives have different directions of action under different circumstances. (1) If is low, , then increasing the incentives for the emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers does not effectively prevent collusion; it even increases the scope for the distribution of effective benefits from collusion. This is because to pay lower emission fees, the emission-producing enterprises want to present lower in their emissions reports. Increasing the incentives for emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers is equivalent to covertly lowering the lower limit of the third-party environmental service providers’ willingness to participate in collusion and the upper limit of the emission-producing enterprises’ collusion-related expenditures (which is also shown in the benefits matrix). (2) If , the incentive for the third-party environmental service provider can effectively prevent collusion, but the incentive to the emission-producing enterprise cannot. At this point, the emission-producing enterprises are limited by the regulatory environment to unilaterally steal emissions and cannot achieve the maximum benefits, but collusion is relatively difficult to detect, so they will choose to collude with the third-party environmental services providers. However, at this point in the limited range of emissions, the benefits that the third-party environmental service providers receive from collusion are limited, the government incentives linked to emission-reduction performance easily break the collusion equilibrium, and the third-party environmental service providers tend to maximize their interest in achieving lower emissions. (3) If is high, , then increasing the incentives for both the emitter and the third-party environmental service provider can help to prevent collusion. At this point in time, emission-producing enterprises are more likely to choose to collude to avoid excessive fines and improve their social image. However, the goal of third-party environmental service providers is to maximize their revenue, and the revenue from collusion is inversely proportional to . In cases of high risk, the increase in incentives makes them aim to obtain more risky returns, the lower limit of acceptable rises, and they aim for a lower , which is contrary to the original intent behind their collusion with emission-producing enterprises, and is likely to trigger a breakdown in their cooperation. As increases, the lower bound of required for collusion rises until it exceeds the upper limit that the firms can afford, at which point the system returns to the equilibrium.

In cases in which is the evolutionarily stable strategy if is the equilibrium point, it is necessary to satisfy , ,, , , and , where, by using the equations and , it can be found that ; by using equations and , it can be found that . The two conclusions are contradictory and, therefore, cannot be satisfied simultaneously. The system cannot form an equilibrium for and at the same time, but in the short term, the emission-producing enterprises’ theft creates disorder in the system and reduces the system’s convergence effect. In the game of collusion between the two sides, there may be collusion failure that occur as a result of uneven distribution of gains, , when the gains from collusion gain cannot satisfy the demands of both sides. However, at this point, the strength of government’s incentivization of the third-party environmental service providers is higher than the pollution-control gains the third-party environmental service providers derive from stealing emissions. The third-party environmental service providers acquiesce to the enterprises’ covert discharging of pollutants, but as the emission-producing enterprises pursuing economic benefits tend to sneak more quantities of pollutants to obtain higher returns, infringing on the third-party environmental service providers ‘ gains, at this point, the emission-producing enterprises are not only regulated by the government, but also by third-party environmental service providers, increasing the probability of violations being discovered, and the emission-producing enterprises gradually regulate their behavior. Therefore, an equilibrium is reached.

If the stability of the system is to be achieved, it should be based on punishment and supplemented by incentives. When collusion occurs frequently, the penalties for emission-producing enterprises as a result of unilateral violation by third-party environmental service providers should be appropriately reduced; in such cases, we have , i.e., Equation (15) does not hold. In this case, considering regulatory costs, emission-producing enterprises decrease their monitoring of third-party environmental service providers. In addition to collusion, the inclination of third-party environmental service providers to unilaterally breach increases due to the expansion of decision paths with potential benefits. However, according to Equation (15), emission-producing enterprises are willing to pay a lower upper limit of the collusion-derived benefits to third-party environmental service providers, and the range of adjustment decreases, intensifying the game between emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers, thereby mitigating the risk of collusion. The incentive effect is optimal only if both parties honor the contract, but in most cases, violation cannot be effectively suppressed. Therefore, the regulation and the number of fines for both parties should be strengthened; in particular, the incentives for emission-producing enterprises should be reduced so that , , and restrict each other, forming . In cases of unevenly distributed benefits, the willingness of both parties to collude is low, but the intensity of government incentives corresponding to small amounts of emissions thefts by is higher than the pollution-control benefits derived from these thefts the third-party environmental service providers, so the third-party environmental service providers acquiesce to the stealing of emissions and leakage by emission-producing enterprises At this point the local government only needs to increase the unilateral regulation of emission-producing enterprises, , prompting their desire for higher risk–reward ratios in situations of high risk, which in turn indirectly influences the interests of third-party environmental service providers and stimulates their spontaneous regulation of the emission-producing enterprises, thus forming the only possible equilibrium in the system.

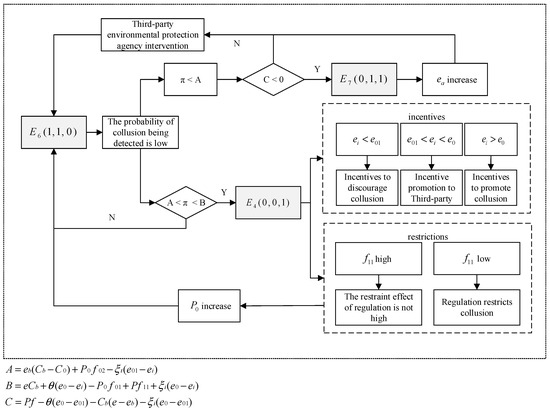

The initial decision-evolution process for each party and the reconciliation process, in which a unique equilibrium is formed after policy adjustments are made, are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The evolution of decision making by parties and their unique equilibrium.

The equilibrium of the system, forming and , is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Analysis of equilibrium-point-stability judgments for (, ).

5. A Numerical Example

The rise of the third-party governance of environmental pollution marks a shift from a one-way regulatory model to a public–private partnership model, but it faces many dilemmas. In addition, the relationship between polluters and pollution treatment companies is tense, with violations ranging from excessive emissions to falsified monitoring data and the illegal dumping and disposal of hazardous waste. As early as the “Top Ten Public Interest Litigation Cases in 2014”, the first of the Taizhou Environmental Protection Federation vs. Jiangsu Changlongnong Chemical Co., Ltd., as well as other environmental-pollution-liability disputes, had a huge impact. Hydrochloric acid, waste sulfuric acid, and other wastes generated by the discharge enterprise in its production process are given to third-party environmental service providers without waste-treatment qualifications at prices ranging from CNY 20 to CNY 100 per ton. Third-party environmental service providers secretly discharged waste into Rutai Canal in Taixing City and Gumagan River in Gaogang District, Taizhou City, resulting in serious pollution of these water bodies. In addition, the phenomenon of emission-producing enterprises stealing and leaking emissions is also common. Since 2010, Tengri Desert pollution incidents have been frequent; in 2014, the RongHua company began production without formal approval, using environmental protection facilities that were not fully complete, and surreptitiously discharged production wastewater into a desert. From 28 May 2014, to 6 March 2015, a total of 271,654 tons of emissions were discharged in this manner. In particular, 187,939 tons were used for the greening irrigation of trees on both sides of the Rongsheng Desert Highway, whose construction was funded by RongHua, and 83,715 tons were discharged directly into the desert hinterland through the concealed pipes laid. In March 2023, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment announced three typical cases of falsification by third-party environmental service providers. In August 2022, for example, the Shanghai Environmental Law Enforcement Headquarters and the Municipal Environmental Monitoring Center jointly conducted a special inspection of ecological and environmental monitoring social service providers and found problems with five automatic monitoring reports on stationary pollution sources issued by Greenske (Shanghai) Environmental Protection Technology Development Co. The company, to ensure that the automatic monitoring comparison results met requirements, deliberately replaced the samples collected on-site as part of the monitoring process with reformulated gas samples, and issued a false monitoring report. The pollution equivalent value of sewage is based on the chemical oxygen demand (COD) of 1 kg, the most important pollutant in sewage, and the unit price of each pollution equivalent is CNY 1.4. The unit price of each pollution equivalent for exhaust gas is USD 1.2. Taking wastewater as an example, this paper assumes that , and based on the above example, takes a value ranging from CNY 20 to CNY 100 per ton, while this paper assumes that yuan.

(1) and are the evolutionarily stable strategy of the system.

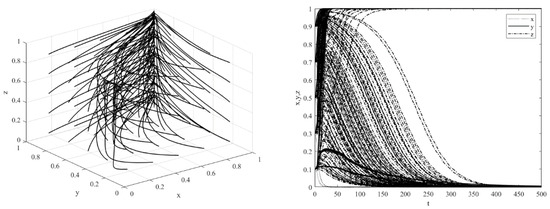

When , , , , , when taking million, million, million, million, million, tons, tons, tons, tons, and tons, , , , , million, million, million, million, million, million, and million. At this point strategy of the system is evolutionarily stable; the evolutionary simulation of this case is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

and are the evolutionarily stable strategy of the system.

The evolution track of the system is shown in Figure 3, where x converges faster than y, and y converges faster than z. It can be seen in Figure 3 that the system is in a disorderly state at this point, the government regulation is weak, and the two interested parties collude out of interest over time, reaching an equilibrium , and we have . At this point, the increase in regulation is not necessarily effective in narrowing the distribution of collusion-related gains, and the incentive differs as the direction of action changes. As increases, the lower bound of required for collusion rises until it exceeds the upper bound that the firm can afford, at which point the system returns to an equilibrium of .

(2) is the only evolutionarily stable strategy for the system.

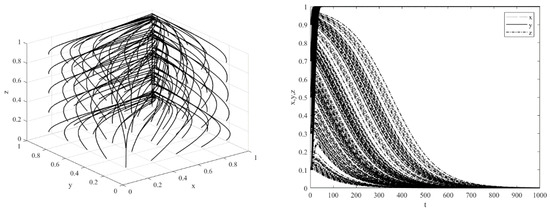

When , , , and each of the following two sets of conditions satisfies at least one of them: 1); ; . 2), ; . Take million, million, million, million, million, tons, tons, tons, tons, and tons, , , , , million, million, million, million, million, million, and million. At this point, is the only evolutionarily stable strategy for the system, and the evolutionary simulation for this case is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

System implementation of unique balance ().

The evolution track of the system is shown in Figure 4, which demonstrates that if the system is to be stable, the local government should focus on penalties and incentives, the focus of regulation should be on the discharge companies, and the incentives should be focused on the third-party environmental service providers. In times of frequent collusion, the likelihood of collusion can be reduced by appropriately lowering the penalties for discharge companies when third-party environmental service providers unilaterally default.

6. Conclusions

Focusing on the moral hazard of third-party environmental service providers in monitoring and controlling the pollutant emissions of enterprises, this paper takes the third-party governance of environmental pollution under the incentive-and-constraint mechanism as its research object. Next, the paper analyzes the intrinsic mechanism of the compliance or default of the emission-producing enterprises and the third-party environmental service providers under different degrees of regulatory constraint and the reasons why it is difficult for the system to form an equilibrium. The paper presents a study of the conditions required for the government’s incentive-and-constraint mechanism to work effectively through dynamic decision making and the transitional conditions necessary for emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers to switch from passive to active pollution management. The study presents the following findings. (1) The potential for spontaneous cooperation between emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers in compliance with contracts related to pollution control. To mitigate collusion, it is advisable to reduce the penalties imposed on emission-producing enterprises when third-party environmental service providers unilaterally breach contracts. In addition to the potential for the division of responsibility for pollution management [31], this paper focuses on the internal game between emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers. Considering the regulatory role played by emission-producing enterprises when third-party environmental service providers unilaterally default, local governments should reduce the proportion of collusion-related resources distributed by emission-producing enterprises to third-party environmental service providers by mobilizing the internal game between the two parties, which can effectively restrain collusion. (2) Reasons why the system is difficult to equalize. Local governments’ goal of avoiding collusion by providing incentives to emission-reduction companies and third-party environmental service providers is limited by the level of falsification of emissions reductions. The government’s incentive-and-constraint mechanism can play a certain role [32], but it has some limitations [33]. This paper view develops the analyses in previous research from a dynamic point of view and further analyzes the reasons why it is difficult for the system to achieve an equilibrium in the long term. When the degree of falsification of emissions reductions is greater, increasing the incentives for emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers cannot be used to effectively prevent collusion; instead it even promotes collusion, because increasing the incentives for both emitters and third-party environmental service providers is tantamount to lowering the lower limit of third-party environmental service providers’ willingness to participate in collusion and the upper limit of emitters’ collusive expenditures. When the level of falsification is moderate, incentives for third-party environmental service providers can effectively prevent collusion, but incentives for emission-producing enterprises cannot. At this point, the maximum potential benefits of unilaterally stealing emissions are not available to emission-producing enterprises, but since collusion is relatively difficult to detect, these enterprises choose to collude with third-party environmental service providers. However, with a limited range of emissions, third-party environmental service providers receive few benefits from collusion, government incentives linked to emission-reduction performance tend to break the collusion equilibrium, and third-party environmental service providers tend to curb pollution and achieve lower emissions based on maximizing their own interests. When the level of falsification is low, increasing the incentives to emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers can help avoid collusion. At this time, emission-producing enterprises are more likely to choose to collude because they want to avoid excessive fines and improve their social image. However, third-party environmental service providers aim to maximize revenues, and in cases of high risk, they are motivated by the associated increases in incentives, the lower limit of acceptable collusion-associated revenue rises, and the service providers’ tendency to falsify their reports increases, which is contrary to the original intention of collusion. This is contrary to the original intent of the collusion of the emission-producing enterprises and can easily lead to a breakdown in cooperation. (3) The impact of dynamic policy changes on the decision making of emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers. Previous studies showed that excessive incentives are not conducive to improving the performance of government regulators and that static incentive-and-constraint mechanisms are inefficient [33], with the distribution of benefits being key [34]. This paper further illustrates the dynamic mechanism of action between emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers, and explains the reasons behind it, thus providing perspectives and rationales for improvement. The uneven distribution of benefits between emission-producing enterprises and third-party environmental service providers can lead to collusion failure. If the prior levels of regulation are not high, collusion does not satisfy the claims of either party, the strength of the incentives provided by local governments to third-party environmental service providers is greater than the pollution-control revenues from the emission reduction, and third-party environmental service providers acquiesce in the emission-reduction behavior of emission-producing enterprises. However, as local government regulation increases, emission-producing enterprises tend to surreptitiously extract greater quantities of pollutants under to obtain higher incentive-based returns, infringing on the gains of third-party environmental service providers. At this point, emission-producing enterprises are not only regulated by the government, but also by the third-party environmental service providers, increasing the probability of the detection of violations. In this way, the activities of emission-producing enterprises are gradually regulated.

Author Contributions

Methodology, R.S.; data curation, Y.Z., D.H. and R.S.; writing—original draft, Y.Z.; writing—review & editing, D.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number 42277484.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Niu, X.; Wang, X.; Gao, J.; Wang, X. Has third-party monitoring improved environmental data quality? An analysis of air pollution data in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 253, 109698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Chen, L.; Feng, L. Effectiveness evaluation on third-party governance model for environmental pollution in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019, 26, 17305–17320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, the General Office of the State Council issued the “Guiding Opinions on Building a Modern Environmental Governance System”. (2020-03-03) [2023-04-23]. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-03/03/content_5486380.htm (accessed on 12 August 2023). (In Chinese)

- Feng, T.; Chen, X.; Ma, J.; Sun, Y.; Du, H.; Yao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, S.; Mi, Z. Air Pollution Control or economic development? Empirical evidence from enterprises with production restrictions. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 336, 117611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, B.; Kuang, H.; Niu, E.; Li, Z. Research on the Transformation Path of the Green Intelligent Port: Outlining the Perspective of the Evolutionary Game ‘Government–Port–Third-Party Organization’. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. Legal liability basis and reasonable boundary of pollution third-party governance. Law Sci. 2018, 6, 182–192. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Z.; Liu, R. Third-party management of environmental pollution in watersheds: Contractual relationships and institutional logic. J. Renmin Univ. China 2019, 33, 150–157. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Tang, J.; Wang, D. Low Carbon Urban Transitioning in Shenzhen: A Multi-Level Environmental Governance Perspective. Sustainability 2016, 8, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Tang, X.; Shen, H. The Relationship between Subjective Status and Corporate Environmental Governance: Evidence from Private Firms in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Zhou, F.; Zhu, Y. Performance-Influencing Factors and Improvement Paths of Third-Party Governance Service Regarding Environmental Pollution—An Empirical Study of the SEM Based on Shanghai Data. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Frutos, J.; Martín-Herrán, G. Spatial vs. non-spatial transboundary pollution control in a class of cooperative and non-cooperative dynamic games. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 276, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Frutos, J.; Martín-Herrán, G. Spatial effects and strategic behavior in a multiregional transboundary pollution dynamic game. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2019, 97, 182–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Fan, T.; Chang, X. Emission reduction technology licensing and diffusion under command-and-control regulation. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2019, 72, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Chen, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, W. Research on the differential game and strategy of water pollution management. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2014, 24, 93–101. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; He, D.; Yan, J.; Tao, L. Mechanism Analysis of Applying Blockchain Technology to Forestry Carbon Sink Projects Based on the Differential Game Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; He, D.; Yan, J. Generation Mechanism of Supply and Demand Gap of Forestry Carbon Sequestration Based on Evolutionary Game: Findings from China. Forests 2022, 13, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, W. Analysis of the evolutionary game between government and emission enterprises under the environmental tax system. Manag. Rev. 2017, 29, 226–236. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Kou, P. Research on the dilemma of environmental pollution management and countermeasures in China from the perspective of a hidden economy. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 30, 73–81. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Sun, X.; Yang, P. Game analysis of government carbon emission regulation under dual governance system. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2017, 27, 21–30. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Pan, F. Incentive Mechanism Analysis of Environmental Governance Using Multitask Principal–Agent Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Ge, G.; Wang, Y. The Impact of Environmental Regulations on Enterprise Pollution Emission from the Perspective of “Overseeing the Government”. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhao, S.; Du, J. Incentive model for third-party treatment of contaminated sites left behind by closed enterprises under the perspective of full linkage responsibility. Syst. Eng.-Theory Pract. 2023, 43, 598–618. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Z.; Bian, C.; Liu, C.; Zhu, J. An evolutionary simulation study of haze pollution, regulatory governance, and public participation. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2019, 29, 101–111. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, K.; Shi, D. The impact of government-enterprise collusion on environmental pollution in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 292, 112744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Ding, Y. Evolutionary game analysis for third-party governance of environmental pollution. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2019, 10, 3143–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; He, D.; Su, H. Evolutionary game analysis of blockchain technology preventing supply chain financial risks. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2824–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Hu, H.; Jin, G. Pollution or innovation? How enterprises react to air pollution under perfect information. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 154821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Ding, H. Research on third-party management of environmental pollution in coal-fired power plants. Resour. Sci. 2019, 41, 326–337. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, S.; Martín-Herrán, G.; Zaccour, G. Dynamic Games in the Economics and Management of Pollution. Environ. Model. Assess. 2010, 15, 433–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, S.; Zaccour, G. Incentive equilibrium strategies and welfare allocation in a dynamic game of pollution control. Automatica 2001, 37, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Dai, Y. Analysis of Strategy Selection in Third-Party Governance of Rural Environmental Pollution. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Xiao, Y. Will Third-Party Treatment Effectively Solve Issues Related to Industrial Pollution in China? Sustainability 2020, 12, 7685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Li, G.; Sun, X. Evolutionary Game Analysis of the Regulatory Strategy of Third-Party Environmental Pollution Management. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Liu, Z. Third-Party Governance of Groundwater Ammonia Nitrogen Pollution: An Evolutionary Game Analysis Considering Reward and Punishment Distribution Mechanism and Pollution Rights Trading Policy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).