Assessing the Impact of Green Training on Sustainable Business Advantage: Exploring the Mediating Role of Green Supply Chain Practices

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Green Training and Development (GTD)

Green Supply Chain Management

3. Sustainable Business Advantage (DV)

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Research Instruments (Questionnaire Design)

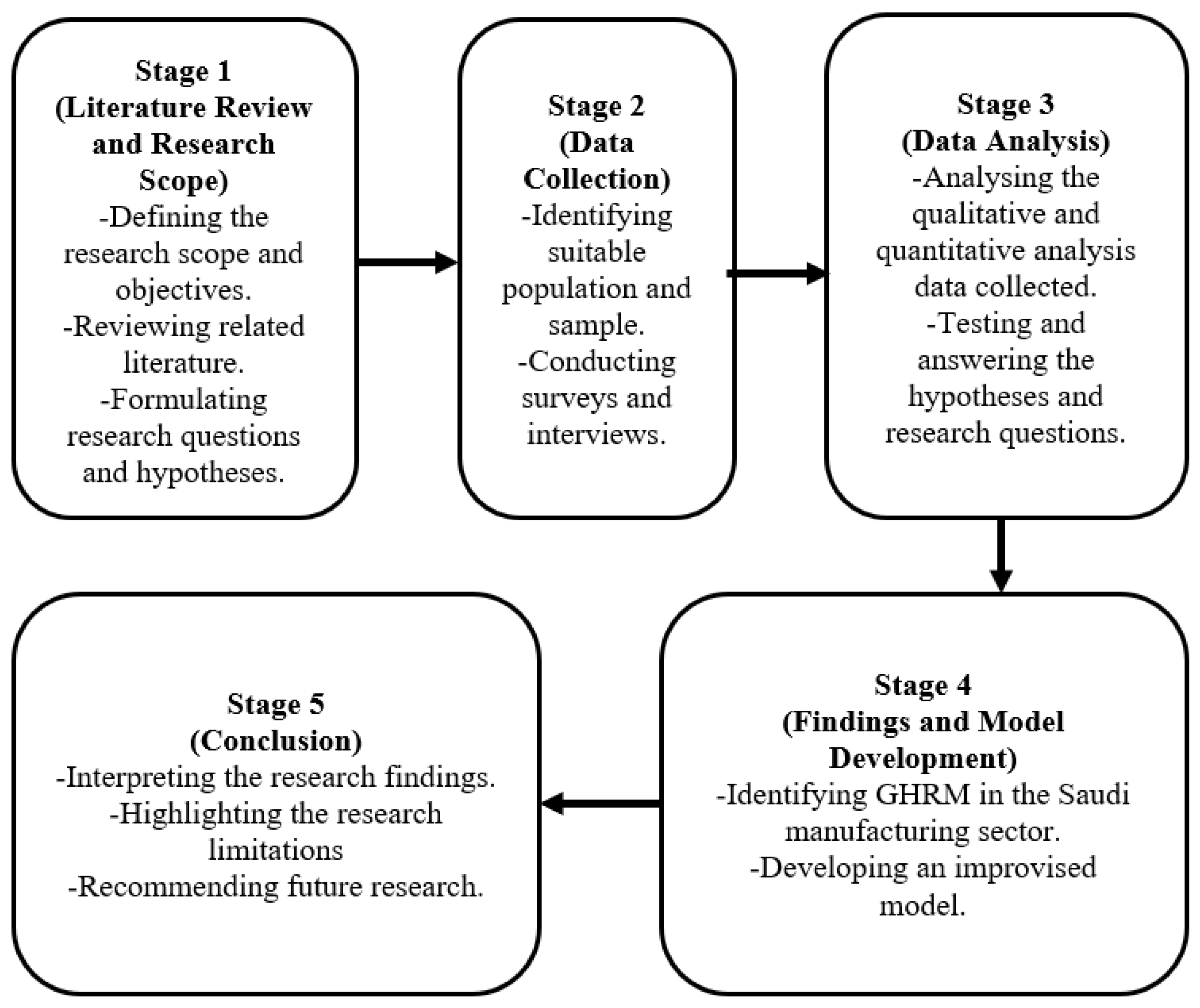

4.2. Research Design

5. Result and Discussion

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Normality Test

5.3. Convergent Validity Assessment

5.4. Measurement Model

5.5. Structural Model

5.6. Hypotheses Testing

5.7. Mediation Model Assessment

6. Discussion

Direct Association between Constructs

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saeed, B.B.; Afsar, B.; Hafeez, S.; Khan, I.; Tahir, M.; Afridi, M.A. Promoting employee’s proenvironmental behavior through green human resource management practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawashdeh, A. The impact of green human resource management on organizational environmental performance in Jordanian health service organizations. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2018, 8, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, B. Impact of Green Marketing on Sustainable Business Development. Cardiff Metropolitan University. Presentation. 2022. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Bharati-Rathore-2/publication/368302925_Impact_of_Green_Marketing_on_Sustainable_Business_Development/links/63e160872f0d126cd18d595e/Impact-of-Green-Marketing-on-Sustainable-Business-Development.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Dao, V.; Langella, I.; Carbo, J. From green to sustainability: Information Technology and an integrated sustainability framework. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2011, 20, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragão, C.G.; Jabbour, C.J.C. Green training for sustainable procurement? Insights from the Brazilian public sector. Ind. Commer. Train. 2017, 49, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A.A.; Jaaron, A.A.; Bon, A.T. The impact of green human resource management and green supply chain management practices on sustainable performance: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brădescu, G. Green logistics—A different and sustainable business growth model. Stud. Bus. Econ. 2014, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Yoo, J. How does open innovation lead competitive advantage? A dynamic capability view perspective. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javad, M.O.M.; Darvishi, M.; Javad, A.O.M. Green supplier selection for the steel industry using BWM and fuzzy TOPSIS: A case study of Khouzestan steel company. Sustain. Futures 2020, 2, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Msigwa, G.; Osman, A.I.; Fawzy, S.; Rooney, D.W.; Yap, P.-S. Circular economy strategies for combating climate change and other environmental issues. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountaine, T.; McCarthy, B.; Saleh, T. Building the AI-powered organization. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2019, 97, 62–73. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, T.; Guillaume, J.H.; Lahtinen, T.J.; Vervoort, R.W. From ad-hoc modelling to strategic infrastructure: A manifesto for model management. Environ. Model. Softw. 2020, 123, 104563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L. Overview of mobile learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Computer Science and Educational Informatization (CSEI), Xinxiang, China, 18–20 June 2021; pp. 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ngoc Su, D.; Luc Tra, D.; Thi Huynh, H.M.; Nguyen, H.H.T.; O’Mahony, B. Enhancing resilience in the COVID-19 crisis: Lessons from human resource management practices in Vietnam. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3189–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Vijayvargy, L. Green supply chain management practices and its impact on organizational performance: Evidence from Indian manufacturers. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2020, 32, 862–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, S. Effects of Green Human Resources Management on Firm Performance: An Empirical Study on Pakistani Firms. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 8, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, A.W.; Creamer, E.G. A grounded theory systematic review of environmental education for secondary students in the United States. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2021, 30, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusliza, M.Y.; Amirudin, A.; Rahadi, R.A.; Nik Sarah Athirah, N.A.; Ramayah, T.; Muhammad, Z.; Dal Mas, F.; Massaro, M.; Saputra, J.; Mokhlis, S. An investigation of pro-environmental behaviour and sustainable development in Malaysia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yuan, L.; Han, G.; Li, H.; Li, P. A Study of the Impact of Strategic Human Resource Management on Organizational Resilience. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Wu, W. How does green innovation improve enterprises’ competitive advantage? The role of organizational learning. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, S.; Subramanian, N.; Jabbour, C.J.; Chong, T. Green human resource management and the enablers of green organisational culture: Enhancing a firm’s environmental performance for sustainable development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar-Sulej, K. Core functions of Sustainable Human Resource Management. A hybrid literature review with the use of H-Classics methodology. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 671–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguntoye, O.; Quartey, S.H. Environmental support programmes for small businesses: A systematic literature review. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2020, 3, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benevene, P.; Buonomo, I. Green human resource management: An evidence-based systematic literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman Khan, S.A.; Yu, Z. Assessing the eco-environmental performance: An PLS-SEM approach with practice-based view. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2021, 24, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpa, V.O.; Mowaiye, B.; Akinlabi, B.H.; Magaji, N. Effect of green human resource management practices and green work life balance on employee retention in selected hospitality firms in lagos and ogun states, Nigeria. Eur. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Stud. 2022, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.S.; Ali, A.; Shaikh, S.A. Impact of Internal Marketing and Human Resource Management to Foster Customer Oriented Behavior among Employees: A Study on Mega Retail Stores in Karachi. NICE Res. J. 2018, 11, 183–199. [Google Scholar]

- Hristov, I.; Chirico, A. The role of sustainability key performance indicators (KPIs) in implementing sustainable strategies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Hardisty, D.J.; Habib, R. The elusive green consumer. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2019, 11, 124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Daily, B.F.; Bishop, J.W.; Massoud, J.A. The role of training and empowerment in environmental performance: A study of the Mexican maquiladora industry. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2012, 32, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J.; Gonzalez-Torre, P.; Adenso-Diaz, B. Stakeholder pressure and the adoption of environmental practices: The mediating effect of training. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaaffar, A.H.; Kaman, Z.K. Green supply chain management practices and environmental performance: A study of employee’s practices in Malaysia Chemical Related Industry. J. Environ. Treat. Tech. 2020, 8, 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, C.; Westbrook, R. New strategic tools for supply chain management. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 1991, 21, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New, S.J.; Payne, P. Research frameworks in logistics: Three models, seven dinners and a survey. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 1995, 25, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A. Blurred boundaries: The discourse of corruption, the culture of politics, and the imagined state. Am. Ethnol. 1995, 22, 375–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, K.W.; Zelbst, P.J.; Meacham, J.; Bhadauria, V.S. Green supply chain management practices: Impact on performance. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beamon, B.M. Designing the green supply chain. Logist. Inf. Manag. 1999, 12, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K.-h. Confirmation of a measurement model for green supply chain management practices implementation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 111, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. The development of green skills through the local TAFE Institute as a potential pathway to regional development. Int. J. Train. Res. 2013, 11, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagell, M.; Shevchenko, A. Why research in sustainable supply chain management should have no future. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 2014, 50, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Dang, W.V.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q. Environmental orientation, green supply chain management, and firm performance: Empirical evidence from chinese small and medium-sized enterprises. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agus, A.; Hajinoor, M.S. Lean production supply chain management as driver towards enhancing product quality and business performance: Case study of manufacturing companies in Malaysia. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2012, 29, 92–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K.h.; Geng, Y. The role of organizational size in the adoption of green supply chain management practices in China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, T.A.; Tat, H.H.; Sulaiman, Z. Green supply chain management, environmental collaboration and sustainability performance. Procedia Cirp 2015, 26, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenaria, Z.D.; Bahramimianroodb, B. Selection of factors affecting the supply chain and green suppliers by the TODIM method in the dairy industry. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 56, 63–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyar, M.N.; Shoukat, A.; Shafique, I. Enhancing firms’ environmental performance and financial performance through green supply chain management practices and institutional pressures. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2019, 11, 451–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A.A.; Sleimi, M. Effect of total quality management on business sustainability: The mediating role of green supply chain management practices. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 66, 524–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, Y.M.; Omar, M.K.; Zaman, M.D.K.; Samad, S. Do all elements of green intellectual capital contribute toward business sustainability? Evidence from the Malaysian context using the Partial Least Squares method. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 234, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasit, Z.A.; Zakaria, M.; Hashim, M.; Ramli, A.; Mohamed, M. Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM) practices for sustainability performance: An empirical evidence of Malaysian SMEs. Int. J. Financ. Res. 2019, 10, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beske, P.; Seuring, S. Putting sustainability into supply chain management. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2014, 19, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervani, A.A.; Helms, M.M.; Sarkis, J. Performance measurement for green supply chain management. Benchmarking: Int. J. 2005, 12, 330–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assumpção, J.J.; Campos, L.M.; Plaza-Úbeda, J.A.; Sehnem, S.; Vazquez-Brust, D.A. Green supply chain management and business innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367, 132877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachon, S.; Klassen, R.D. Extending green practices across the supply chain: The impact of upstream and downstream integration. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2006, 26, 795–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.C.; Liguori, E.W. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intentions: Outcome expectations as mediator and subjective norms as moderator. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 26, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, P.C.; Seuring, S. Extending the reach of multi-tier sustainable supply chain management–insights from mineral supply chains. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 217, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, A.; Das, R.; De, P.K.; Sana, S.S. Optimal Pricing and Greening Strategy in a Competitive Green Supply Chain: Impact of Government Subsidy and Tax Policy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, A.; De, P.K.; Chakraborty, A.K.; Lim, C.P.; Das, R. Optimal pricing policy in a three-layer dual-channel supply chain under government subsidy in green manufacturing. Math. Comput. Simul. 2023, 204, 401–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arqawi, S.; Zaid, A.A.; Jaaron, A.A.; Al Hila, A.A.; Al Shobaki, M.J.; Abu-Naser, S.S. Green human resource management practices among Palestinian manufacturing firms-an exploratory study. J. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2019, 59, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Long, G. How Should Civil Society Stakeholders Report Their Contribution to the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development? 2018. Available online: https://ocm.iccrom.org/documents/how-should-civil-society-stakeholders-report-their-contribution-implementation-2030 (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Saha, N.; Gregar, A. Human resource management: As a source of sustained competitive advantage of the firms. Int. Proc. Econ. Dev. Res. 2012, 46, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.H.; Nobeoka, K. Creating and managing a high-performance knowledge-sharing network: The Toyota case. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sum, V. Integrating training in business strategies means greater impact of training on the firm’s competitiveness. Res. Bus. Econ. J. 2011, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar Mishra, A. Influential marketing strategies adopted by the cement industries. Int. J. Res.-GRANTHAALAYAH 2019, 7, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H. The influence of corporate environmental ethics on competitive advantage: The mediation role of green innovation. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Lai, S.-B.; Wen, C.-T. The influence of green innovation performance on corporate advantage in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, M.; Rabiei, S.; Jabbour, C.J.C. Envisioning the invisible: Understanding the synergy between green human resource management and green supply chain management in manufacturing firms in Iran in light of the moderating effect of employees’ resistance to change. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, B.F.; Huang, S.C. Achieving sustainability through attention to human resource factors in environmental management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2001, 21, 1539–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green human resource management: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P. Green recruitment and selection: An insight into green patterns. Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 41, 258–272. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; Tang, G.; Jackson, S.E. Green human resource management research in emergence: A review and future directions. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2018, 35, 769–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Industry structure and competitive strategy: Keys to profitability. Financ. Anal. J. 1980, 36, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caves, R.E. Economic analysis and the quest for competitive advantage. Am. Econ. Rev. 1984, 74, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Besanko, D.D.; Mark, S.; Scott, S. Economics of Strategy, 6th ed.; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, L.; Dubois, A.; Gadde, L.E. The multiple boundaries of the firm. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 1255–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladino, A. Investigating the drivers of innovation and new product success: A comparison of strategic orientations. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2007, 24, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, A.; Gregory, M.; Platts, K. Performance measurement system design: A literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 1228–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenhall, R.H.; Langfield-Smith, K. Multiple perspectives of performance measures. Eur. Manag. J. 2007, 25, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garengo, P.; Biazzo, S.; Bititci, U.S. Performance measurement systems in SMEs: A review for a research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2005, 7, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, K.A. Measuring general managers’ performances: Market, accounting and combination-of-measures systems. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2006, 19, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, S.J.; Coote, L.V. Organizational culture, innovation, and performance: A test of Schein’s model. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1609–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, A.; Mahbod, M.A. Prioritization of key performance indicators: An integration of analytical hierarchy process and goal setting. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2007, 56, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publications: Southend Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; Phillips, L.W. Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Shi, Z.; Qin, C.; Tao, L.; Liu, X.; Xu, F.; Zhang, L.; Song, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. Therapeutic target database update 2012: A resource for facilitating target-oriented drug discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D1128–D1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradeke, F.T.; Ishola, G.K.; Okikiola, O.L. Green Training and Development Practices on Environmental Sustainability: Evidence from WAMCO PLC. J. Educ. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2021, 2, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, C.; Tachizawa, E.M. Extending sustainability to suppliers: A systematic literature review. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yafi, E.; Tehseen, S.; Haider, S.A. Impact of green training on environmental performance through mediating role of competencies and motivation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors affecting green purchase behaviour and future research directions. Int. Strateg. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaleb, E.A.; Dominic, P.D.D.; Singh, N.S.S.; Naji, G.M.A. Assessing the big data adoption readiness role in healthcare between technology impact factors and intention to adopt big data. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amruha, V.N.; Geetha, S.N. Linking organizational green training and voluntary workplace green behavior: Mediating role of green supporting climate and employees’ green satisfaction. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 290, 125876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejazi, S.Y.; Sadoughi, M. How does teacher support contribute to learners’ grit? The role of learning enjoyment. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2023, 17, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoraiki, M.; Ahmad, A.R.; Ateeq, A.A.; Naji, G.M.A.; Almaamari, Q.; Beshr, B.A.H. Impact of Teachers’ Commitment to the Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Sustainable Teaching Performance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S/N | Socio-Demographic Characteristics | Categories |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | What is your gender? | [] Male [] Female |

| 2 | What is your age? | [] 20–29 years [] 30–39 years [] 40–49 years [] 50 years & above |

| 3 | What is your highest educational qualification? | [] O-level & below [] Bachelors’ degree [] Masters’ degree [] Others, Please Specify …………………………. ………………………… |

| 4 | How long have you been working with your company? | [] 0–4 years [] 5–9 years [] 10–14 years [] 15–19 years [] 20 years & above |

| 5 | How would you classify your work position in your organisation? | [] Senior Staff [] Management Staff [] Junior Staff [] Contract Staff |

| Variables | Items Numbers | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Training and Development | GTD1 | 1 | 5 | 3.74 | 1.148 |

| GTD2 | 1 | 5 | 3.68 | 1.088 | |

| GTD3 | 1 | 5 | 3.62 | 1.145 | |

| GTD4 | 1 | 5 | 3.64 | 1.123 | |

| GTD5 | 1 | 5 | 3.71 | 1.119 | |

| GTD6 | 1 | 5 | 4.06 | 1.082 | |

| GTD7 | 1 | 5 | 3.61 | 1.219 | |

| GTD8 | 1 | 5 | 3.67 | 1.111 | |

| GTD9 | 1 | 5 | 3.74 | 1.137 | |

| GTD10 | 1 | 5 | 3.86 | 1.072 | |

| Green Supply Chain Management | GSC1 | 1 | 5 | 3.87 | 1.101 |

| GSC2 | 1 | 5 | 3.55 | 1.144 | |

| GSC3 | 1 | 5 | 3.93 | 0.976 | |

| GSC4 | 1 | 5 | 4.18 | 0.995 | |

| GSC5 | 1 | 5 | 4.04 | 0.999 | |

| GSC6 | 1 | 5 | 4.10 | 1.059 | |

| Sustainable Business Advantage | SBA1 | 1 | 5 | 4.22 | 1.027 |

| SBA2 | 1 | 5 | 3.94 | 1.047 | |

| SBA3 | 1 | 5 | 3.86 | 0.969 | |

| SBA4 | 1 | 5 | 3.31 | 1.105 | |

| SBA5 | 1 | 5 | 3.43 | 1.079 |

| Variables | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|

| Green Training and Development | 0.118 | 0.136 |

| Green Recruitment | 0.036 | −0.261 |

| Green Supply Chain Management | −0.268 | 0.232 |

| Sustainable Business Advantage | −0.023 | −0.109 |

| CR | AVE | MSV | MaxR(H) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Green Training | 0.95 | 0.63 | 0.039 | 0.945 | 0.795 | |||

| 2. Green Recruitment and Selection | 0.94 | 0.66 | 0.104 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.814 | ||

| 3. Green Supply Chain | 0.9 | 0.59 | 0.226 | 0.896 | 0.176 *** | 0.322 *** | 0.767 | |

| 4. Sustainable Business Advantage | 0.89 | 0.62 | 0.226 | 0.891 | 0.199 *** | 0.310 *** | 0.476 *** | 0.788 |

| Outcome Variables | Predictors | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Supply Chain | <--- | Green Training | 0.157 | 0.04 | 3.64 | *** | Supported |

| Sustainable Business Advantage | <--- | Green Supply Chain | 0.399 | 0.05 | 8.31 | *** | Supported |

| Sustainable Business Advantage | <--- | Green Training | 0.118 | 0.04 | 2.88 | *** | Supported |

| Mediation Effect | Direct Effect X→Y | Indirect Effect | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Training and Development → Green Supply Chain → Sustainable Business Advantage | 0.157 (0.021 *) | 0.063 (0.020 *) | Partial Mediation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barakat, B.; Milhem, M.; Naji, G.M.A.; Alzoraiki, M.; Muda, H.B.; Ateeq, A.; Abro, Z. Assessing the Impact of Green Training on Sustainable Business Advantage: Exploring the Mediating Role of Green Supply Chain Practices. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14144. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914144

Barakat B, Milhem M, Naji GMA, Alzoraiki M, Muda HB, Ateeq A, Abro Z. Assessing the Impact of Green Training on Sustainable Business Advantage: Exploring the Mediating Role of Green Supply Chain Practices. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14144. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914144

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarakat, Bashar, Marwan Milhem, Gehad Mohammed Ahmed Naji, Mohammed Alzoraiki, Habsah Binti Muda, Ali Ateeq, and Zahida Abro. 2023. "Assessing the Impact of Green Training on Sustainable Business Advantage: Exploring the Mediating Role of Green Supply Chain Practices" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14144. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914144

APA StyleBarakat, B., Milhem, M., Naji, G. M. A., Alzoraiki, M., Muda, H. B., Ateeq, A., & Abro, Z. (2023). Assessing the Impact of Green Training on Sustainable Business Advantage: Exploring the Mediating Role of Green Supply Chain Practices. Sustainability, 15(19), 14144. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914144