A Framework for Sustainability Reporting of Renewable Energy Companies in Greece

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Baseline

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

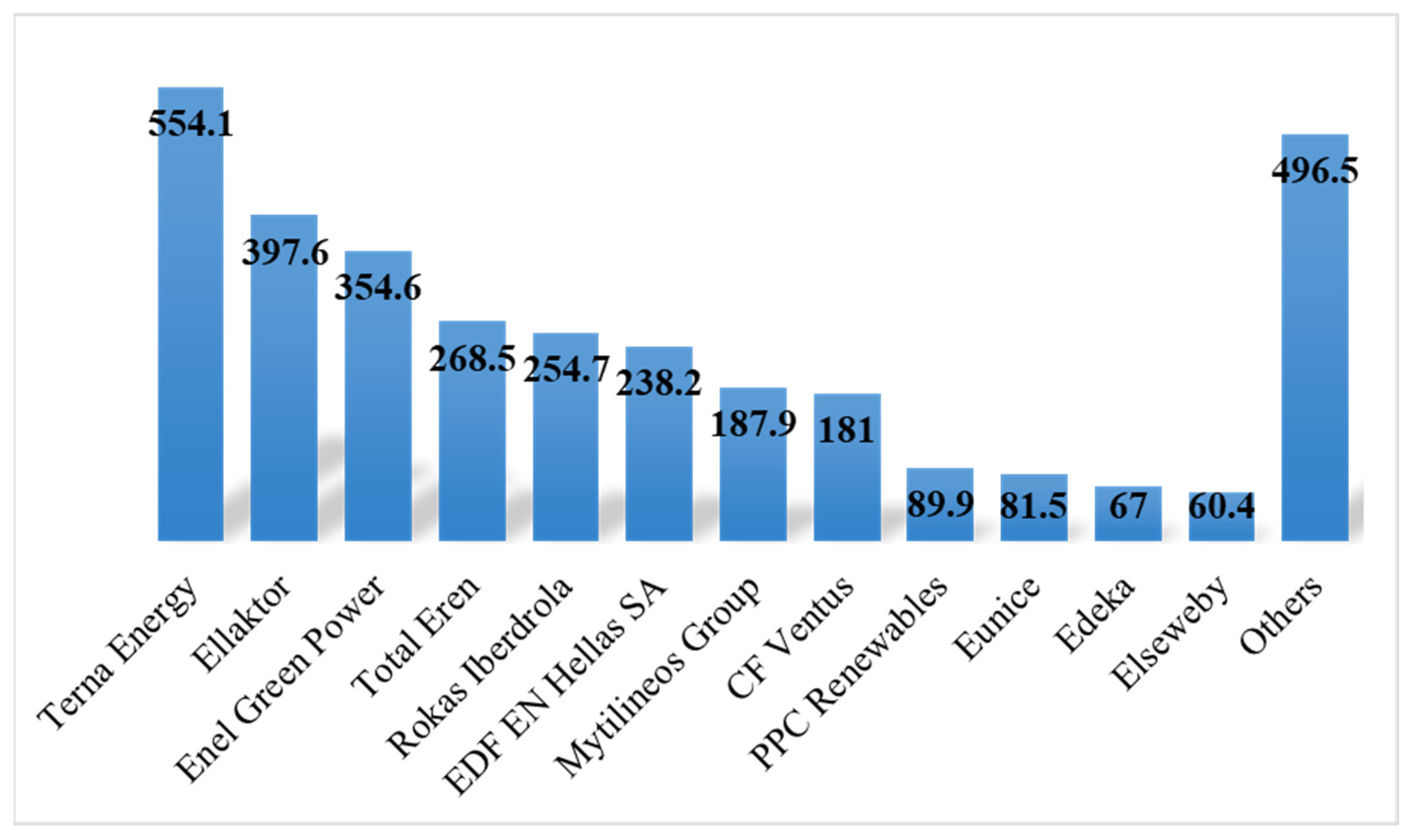

4.1. Leading RES OPERATORS in Greece

4.2. Leading Wind-Turbine Manufacturing Companies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guchhait, R.; Sarkar, B. Increasing Growth of Renewable Energy: A State of Art. Energies 2023, 16, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, M.K.G.; Sameeroddin, M.; Abdul, D.; Sattar, M.A. Renewable energy in the 21st century: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 80, 1756–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, G.; D’Alessandro, S. Societal implications of sustainable energy action plans: From energy modelling to stakeholder learning. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwuigbe, U.; Teddy, O.; Uwuigbe, O.R.; Emmanuel, O.; Asiriuwa, O.; Eyitomi, G.A.; Taiwo, O.S. Sustainability reporting and firm performance: A bi-directional approach. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rudito, B.; Famiola, M.; Anggahegari, P. Corporate Social Responsibility and Social Capital: Journey of Community Engage-ment toward Community Empowerment Program in Developing Country. Sustainability 2023, 15, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Khan, I. CSR Influence on Brand Loyalty in Banking: The Role of Brand Credibility and Brand Identification. Sustainability 2023, 15, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rodríguez, F.J.; García-Rodríguez, J.L.; Castilla-Gutiérrez, C.; Major, S.A. Corporate Social Responsibility of Oil Companies in Developing Countries: From Altruism to Business Strategy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Chen, Z. Who can realize the “spot value” of corporate social responsibility? Evidence from Chinese investors’ profiles. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2020, 11, 717–743. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Sun, H.; Shen, H.; Lin, Y. Corporate Social Responsibility Information Disclosure and Financial Performance: Is Green Technology Innovation a Missing Link? Sustainability 2023, 15, 11926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latapí Agudelo, M.A.; Jóhannsdóttir, L.; Davídsdóttir, B. A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockett, A.; Moon, J.; Visser, W. Corporate Social Responsibility in Management Research: Focus, Nature, Salience and Sources of Influence. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, W.C. Corporate social responsibility: Deep roots, flourishing growth, promising future. In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility; Crane, A., McWilliams, A., Matten, D., Moon, J., Siegel, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 522–531. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A. Corporate social responsibility: The centerpiece of competing and complementary frameworks. Organ. Dyn. 2015, 44, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, Q. The Quality of Corporate Social Responsibility Information Disclosure and Enterprise Innovation: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Jin, S. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability: From a Corporate Governance Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Hu, H.; Wang, Y. Fuzzy Front-End Vertical External Involvement, Corporate Social Responsibility and Firms’ New Product Development Performance in the VUCA Age: From an Organizational Learning Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikas, A.; Neofytou, H.; Karamaneas, A.; Koasidis, K.; Psarras, J. Sustainable and socially just transition to a post-lignite era in Greece: A multi-level perspective. Energy Sources Part B Econ. Plan. Policy 2020, 15, 513–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nytimes. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/29/business/greece-green-energy-climate-eu.html (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Bithas, K. The use of renewable energy resources in Greece. Int. J. Environ. Technol. Manag. 2001, 1, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, P.A.; Asumadu-Sarkodie, S. A review of renewable energy sources, sustainability issues and climate change mitigation. Cogent Eng. 2016, 3, 1167990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirasgedis, S.; Sarafidis, Y.; Georgopoulou, E.; Lalas, D. The role of renewable energy sources within the framework of the Kyoto Protocol: The case of Greece. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2002, 6, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarquinio, L.; Raucci, D.; Benedetti, R. An Investigation of Global Reporting Initiative Performance Indicators in Corporate Sustainability Reports: Greek, Italian and Spanish Evidence. Sustainability 2018, 10, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. KPMG Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2011; KPMG: Zurich, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- KPMG. KPMG. KPMG currents of change. In The KPMG Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2015; KPMG: Zurich, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- KPMG. KPMG Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2013; KPMG: Zurich, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC). The International Framework; IIRC: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- KPMG. Carrots & Sticks. In GRI, UNEP and Centre for Corporate Governance in Africa 2016; KPMG: Zurich, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- GRI. Sustainability Reporting Guidelines on Economic, Environmental, and Social Performance; GRI: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- GRI. Global Sustainability Standard Board (GSSB), Consolidated Set of GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards 2016; GRI: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rahdari, A.H.; Rostamy, A.A. Designing a general set of sustainability indicators at the corporate level. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 757–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Ren, L.; Qiao, J.; Yao, S.; Strielkowski, W.; Streimikis, J. Corporate Social Responsibility and Corruption: Implications for the Sustainable Energy Sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A.; Frost, G.R. Integrating sustainability reporting into management practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 32, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasch, C. Environmental performance evaluation and indicators. J. Clean. Prod. 2000, 8, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodhia, S.; Martin, N. Corporate sustainability indicators: An Australian mining case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 84, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Burritt, R. Contemporary Environmental Accounting; Greenleaf Publishing Limited: Sheffield, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Paravantis, J.; Stigka, E.; Mihalakakou, G. An analysis of public attitudes towards renewable energy in Western Greece. In Proceedings of the IISA 2014, The 5th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems and Applications, Crete, Greece, 7–9 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Karytsas, S.; Theodoropoulou, H. Socioeconomic and demographic factors that influence publics’ awareness on the different forms of renewable energy sources. Renew. Energy 2014, 71, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntanos, S.; Kyriakopoulos, G.; Chalikias, M.; Arabatzis, G.; Skordoulis, M.; Galatsidas, S.; Drosos, D. A Social Assessment of the Usage of Renewable Energy Sources and Its Contribution to Life Quality: The Case of an Attica Urban Area in Greece. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaprakakis, D.A.; Christakis, D.G. The exploitation of electricity production projects from Renewable Energy Sources for the social and economic development of remote communities. The case of Greece: An example to avoid. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metaxas, A.; Tsinisizelis, M. The Development of Renewable Energy Governance in Greece. Examples of a Failed (?) Policy. In Renewable Energy Governance: Complexities and Challenges; Springer: London, UK, 2013; Volume 23, pp. 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Tourkolias, C.; Mirasgedis, S. Quantification and monetization of employment benefits associated with renewable energy technologies in Greece. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 2876–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xydis, G.; Loizidou, M.; Koroneos, C. Multicriteria analysis of Renewable Energy Sources (RES) utilisation in waste treatment facilities: The case of Chania prefecture, Greece. Int. J. Environ. Waste Manag. 2010, 6, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldellis, J.K.; Zafirakis, D. Prospects and challenges for clean energy in European Islands. TILOS Paradig. Renew. Energy 2020, 145, 2489–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, A. Renewable energy resources and sustainable development in Mykonos (Greece). Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 1496–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafirakis, D.; Chalvatzis, K.; Kaldellis, J.K. “Socially just” support mechanisms for the promotion of renewable energy sources in Greece. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 21, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakka, E.G.; Bilionis, D.V.; Vamvatsikos, D.; Gantes, C.J. Onshore wind farm siting prioritization based on investment prof-itability for Greece. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 2827–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantidis, J.G.; Bandekas, D.V.; Potolias, C.; Vordos, N. Cost of PV electricity—Case study of Greece. Sol. Energy 2013, 91, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltas, A.E.; Dervos, A.N. Special framework for the spatial planning & the sustainable development of renewable energy sources. Renew. Energy 2012, 48, 358–363. [Google Scholar]

- Alola, A.A.; Alola, U.V.; Akadiri, S.S. Renewable energy consumption in Coastline Mediterranean Countries: Impact of environmental degradation and housing policy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 25789–25801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doukas, H.; Marinakis, V.; Psarras, J. “Greening” the Hellenic Corporate Energy Policy: An Integrated Decision Support Framework. Int. J. Green Energy 2012, 9, 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, E.M.; Dumontier, P.; Feleaga, N.; Feleaga, L. A Proposal of an International Environmental Reporting Grid: What Interest for Policymakers, Regulatory Bodies, Companies, and Researchers?: Reply to Discussion of “Mandatory Environmental Disclosures by Companies Complying with IAS/IFRS: The Case of France, Germany and the UK”. Int. J. Account. 2014, 49, 253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Metaxas, T.; Tsavdaridou, M. Environmental Policy and CSR in Petroleum Refining Companies in Greece: Content and Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Analysis. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2017, 19, 1750012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ralston, D.A. Corporate social responsibility in Europe and the U.S.: Insights from businesses’ self-presentation. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2002, 33, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, M.J.; Adler, R.W. Exploring the reliability of social and environmental disclosures content analysis. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1999, 12, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieminen, T.; Niskanen, J. The objectivity of corporate environmental re-porting: A study of Finnish listed firms’ environmental disclosures. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2001, 10, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Patten, D.M.; Crampton, W. Legitimacy and the internet: An examination of corporate web page environmental disclosures. Adv. Environ. Account. Manag. 2004, 2, 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- Berelson, B. Content Analysis in Communication Research; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, W.F.; Monsen, R.J. On the Measurement of Corporate Social Responsibility: Self-Reported Disclosures as a Method of Measuring Corporate Social Involvement. Acad. Manag. J. 1979, 22, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HWEA. HWEA Wind Energy Statistics 2019. [Press Release]. 2019. Available online: https://eletaen.gr/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/2019-hwea-statistics-greece-upd-6-2020.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2020).

- Terna. Corporate Responsibility Reports. [Press Release]. 2020. Available online: https://www.terna-energy.com/esg/csr-reports/ (accessed on 17 July 2020).

- Ellaktor. Sustainability Reports. [Press Release]. 2020. Available online: https://ellaktor.com/en/sustainability-reports/ (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Enel. Sustainability. [Press Release]. 2020. Available online: https://www.enel.com/investors/sustainability (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Eren. Our CSR Reports. [Press Release]. 2020. Available online: https://www.sustainable-performance.total.com/en/reporting/our-csr-reports (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Iberdrola. Annual Reports. [Press Release]. 2019. Available online: https://www.iberdrola.com/shareholders-investors/annual-reports/2019 (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- EDF. Environmental, Societal and Human Resources Information. [Press Release]. 2020. Available online: https://www.edf.fr/en/our-commitments/reports (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Mytilineos. Reports and Studies. [Press Release]. 2020. Available online: https://www.mytilineos.gr/en-us/csr-reports/publications (accessed on 11 July 2020).

- PPC. Publications for C.S.R. [Press Release]. 2020. Available online: https://www.dei.gr/en/i-dei/etairiki-koinwniki-euthuni/entupa-gia-etairiki-koinwniki-euthuni (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Eunice. Corporate Social Responsibility. [Press Release]. 2020. Available online: http://eunice-group.com/csr/ (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Edeka. Edeka SA. [Press Release]. 2020. Available online: https://edeka.com.gr/el/ (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Elsewedy. Sustainability Report. [Press Release]. 2017. Available online: https://elsewedyelectric.com/en/sustainability/ (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Liaggou, C. Which Companies Are Dynamically Expanding in RES. Kathimerini. Available online: https://www.kathimerini.gr/1059714/article-/oikonomia/epixeirhseis/poies-etaireies-epekteinontai-dynamika-stis-ape (accessed on 17 July 2020).

- Vestas. The Vestas Sustainability Report. [Press Release]. 2019. Available online: https://www.vestas.com/~/media/vestas/investor/investor%20pdf/financial%20reports/2019/q4/sustainabilityreport_2019.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- Enercon. Sustainability. [Press Release]. 2020. Available online: https://www.enercon.de/en/products/ep-8/e-126/ (accessed on 26 July 2020).

- SGRE. Consolidated Non-Financial Statement [Press Release]. 2019. Available online: https://www.siemensgamesa.com/-/media/siemensgamesa/downloads/en/sustainability-/siemens-gamesa-consolidated-non-financial-statement-2019-en.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Nordex. Sustainable Report 2019. [Press Release]. 2019. Available online: https://www.nordex-online.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/04/200421_Nordex_NHB_2019_en_web.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- GERE. GE Environmental, Social and Governance. Available online: https://www.ge.com/sustainability (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- UNGC. Communication on Progress: UN Global Compact. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/participation/report/cop (accessed on 30 July 2020).

| Company | Capacity (MW) | CSR Report | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terna Energy | 554.1 | Yes | [61] |

| Ellaktor | 397.6 | Yes | [62] |

| Enel Green Power | 354.6 | Yes | [63] |

| Total Eren | 268.5 | Yes | [64] |

| Iberdrola Rokas | 254.7 | Yes | [65] |

| Edf En Hellas SA | 238.2 | Yes | [66] |

| Mytilineos Group | 187.9 | Yes | [67] |

| Cf Ventus | 181 | No | - |

| PPC Renewables | 89.9 | Yes | [68] |

| Eunice | 81.5 | No | [69] |

| Edeka | 67 | No | [70] |

| Elsewedy | 60.4 | Yes | [71] |

| GRI Standards | Disclosure | GRI Code | Terna Energy 2018 | Ellaktor 2019 | Enel Green Power 2019 | Total Eren 2019 | Rokas Iberdrola 2019 | EDF EN Hellas 2018 | Mytilineos 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foundation 2016 | 101 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| GENERAL DISCLOSURES 2016 GRI 102 | Organizational profile | Name of the organization | 102-1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Activities, brands, products and services | 102-2 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Location and headquarters | 102-3 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Location of operations | 102-4 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Ownership and legal form | 102-5 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Markets served | 102-6 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Scale of the organization | 102-7 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Information on employees and other workers | 102-8 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Supply chain | 102-9 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Significant changes to the organization and its supply chain | 102-10 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Precautionary principle or approach | 102-11 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| External initiatives | 102-12 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Membership of associations | 102-13 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Strategy | Statement from senior decision maker | 102-14 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Key impacts, risks, and opportunities | 102-15 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Ethics and integrity | Values, principles, standards, and norms of behavior | 102-16 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Location and headquarters | 102-17 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Governance | Mechanisms for advice and concerns about ethics | 102-18 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Governance structure | 102-19 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Delegating authority | 102-20 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Executive-level responsibility for economic, environmental, and social topics | 102-21 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Consulting stakeholders on economic, environmental, and social topics | 102-22 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Chair of the highest governance body | 102-23 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Nominating and selecting the highest governance body | 102-24 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Conflicts of interest | 102-25 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Role of highest governance body in setting purpose, values, and strategy | 102-26 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Collective knowledge of highest governance body | 102-27 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Evaluating the highest governance body’s performance | 102-28 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Identifying and managing economic, environmental, and social impacts | 102-29 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Effectiveness of risk management processes | 102-30 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Review of economic, environmental and social issues | 102-31 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Highest governance body’s role in sustainability reporting | 102-32 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Communicating critical concerns | 102-33 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Nature and total number of critical concerns | 102-34 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Remuneration policies | 102-35 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Process for determining remuneration | 102-36 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Stakeholders’ involvement in remuneration | 102-37 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Annual total compensation ratio | 102-38 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Percentage increase in annual total compensation ratio | 102-39 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Stakeholder engagement | List of stakeholder groups | 102-40 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Collective bargaining agreements | 102-41 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Identifying and selecting stakeholders | 102-42 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Approach to stakeholder engagement | 102-43 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Key topics and concerns raised | 102-44 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Reporting practice | Entities included in the consolidated financial statements | 102-45 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Defining report content and topic boundaries | 102-46 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| List of material topics | 102-47 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Restatements of information | 102-48 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Changes in reporting | 102-49 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Reporting period | 102-50 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Date of most recent report | 102-51 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Reporting cycle | 102-52 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Contact point for questions regarding the report | 102-53 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Claims of reporting in accordance with the GRI Standards | 102-54 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| GRI content index | 102-55 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| External assurance | 102-56 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| MANAGEMENT APPROACH 2016 GRI 103 | Explanation of the material topic and its boundary | 103-1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| The management approach and its components | 103-2 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Evaluation of the management approach | 103-3 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| ECONOMIC STANDARD SERIES GRI 200 | Economic Performance 2016 GRI 201 | Direct economic value generated and distributed | 201-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ |

| Financial implications and other risks and opportunities due to climate change | 201-02 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | ||

| Defined-benefit plan obligations and other retirement plans | 201-03 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | ||

| Financial assistance received from government | 201-04 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Market Presence 2016 GRI 202 | Ratios of standard entry-level wage by gender compared to local minimum wage | 202-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | |

| Proportion of senior management hired from the local community | 202-02 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Indirect Economic Impacts 2016 GRI 203 | Infrastructure investments and services supported | 203-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Significant indirect economic impacts | 203-02 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Procurement Practices 2016 GRI 204 | Proportion of spending on local suppliers | 204-01 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | |

| Anti-corruption 2016 GRI 205 | Operations assessed for risks related to corruption | 205-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | |

| Communication and training about anti-corruption policies and procedures | 205-02 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Confirmed incidents of corruption and actions taken | 205-03 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Anti-competitive Behavior 2016 GRI 206 | Legal actions for anti-competitive behavior, anti-trust, and monopoly practices | 206-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | |

| Tax 2019 GRI 207 | Approach to tax | 207-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | |

| Tax governance, control, and risk management | 207-02 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Stakeholder engagement and management of concerns related to tax | 207-03 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Country-by-country reporting | 207-04 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| ENVIRONMENTAL STANDARDS SERIES GRI 300 | Materials 2016 GRI 301 | Materials used by weight or volume | 301-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ |

| Recycled input materials used | 301-02 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Reclaimed products and their packaging materials | 301-03 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Energy 2016 GRI 302 | Energy consumption within the organization | 302-01 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Energy consumption outside of the organization | 302-02 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Energy intensity | 302-03 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ✔ | ||

| Reduction in energy consumption | 302-04 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Reduction in energy requirements of products and services | 302-05 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Water and Effluents 2018 GRI 303 | Interactions with water as a shared resource | 303-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Management of water discharge-related impacts | 303-02 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | ||

| Water withdrawal | 303-03 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | ||

| Water discharge | 303-04 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Water consumption | 303-05 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | ||

| Biodiversity 2016 GRI 304 | Operational sites owned, leased, managed in, or adjacent to, protected areas and areas of high biodiversity value outside protected areas | 304-01 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | |

| Significant impacts of activities, products, and services on biodiversity | 304-02 | ✔ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | ||

| Habitats protected or restored | 304-03 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| IUCN Red List species and national-conservation-listed species with habitats in areas affected by operations | 304-04 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Emissions 2016 GRI 305 | Direct (Scope 1) GHG emissions | 305-01 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | |

| Energy indirect (Scope 2) GHG emissions | 305-02 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | ||

| Other indirect (Scope 3) GHG emissions | 305-03 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| GHG emission intensity | 305-04 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Reduction in GHG emissions | 305-05 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Emissions of ozone-depleting substances (ODS) | 305-06 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ✔ | ||

| Nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulfur oxides (SOx), and other significant air emissions | 305-07 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Effluents and Waste 2016 GRI 306 | Water discharge by quality and destination | 306-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Waste by type and disposal method | 306-02 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Significant spills | 306-03 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | ||

| Transport of hazardous waste | 306-04 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Water bodies affected by water discharges and/or runoff | 306-05 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Environmental Compliance 2016 GRI 307 | Non-compliance with environmental laws and regulations | 307-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | |

| Supplier Environmental Assessment 2016 GRI 308 | New suppliers that were screened using environmental criteria | 308-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | |

| Negative environmental impacts in the supply chain and actions taken | 308-02 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| SOCIAL STANDARDS SERIES GRI 400 | Employment 2016 GRI 401 | New employee hires and employee turnover | 401-01 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Benefits provided to full-time employees that are not provided to temporary or part-time employees | 401-02 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | ||

| Parental leave | 401-03 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | ||

| Labor/Management Relations 2016 GRI 402 | Minimum notice periods regarding operational changes | 402-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | |

| Occupational Health and Safety 2018 GRI 403 | Occupational health and safety management system | 403-01 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | |

| Hazard identification, risk assessment, and incident investigation | 403-02 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Occupational health services | 403-03 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | |||

| Worker participation, consultation, and communication on occupational health and safety | 403-04 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Worker training on occupational health and safety | 403-05 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Promotion of worker health | 403-06 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Prevention and mitigation of occupational health and safety impacts directly linked by business relationships | 403-07 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Workers covered by an occupational health and safety management system | 403-08 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Work-related injuries | 403-09 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Work-related ill health | 403-10 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | |||

| Training and Education 2016 GRI 404 | Average hours of training per year per employee | 404-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Programs for upgrading employee skills and transition assistance programs | 404-02 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | ||

| Percentage of employees receiving regular performance and career-development reviews | 404-03 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Diversity and Equal Opportunity 2016 GRI 405 | Diversity of governance bodies and employees | 405-01 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | |

| Ratio of basic salary and remuneration of women to men | 405-02 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Non-discrimination 2016 GRI 406 | Incidents of discrimination and corrective actions taken | 406-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | |

| Freedom of Association and Collective Bargaining 2016 GRI 407 | Operations and suppliers in which the right to freedom of association and collective bargaining may be at risk | 407-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | |

| Child Labor2016 GRI 408 | Operations and suppliers at significant risk for incidents of child labor | 408-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | |

| Forced or Compulsory Labor 2016 GRI 409 | Operations and suppliers at significant risk for incidents of forced or compulsory labor | 409-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | |

| Security Practices 2016 GRI 410 | Security personnel trained in human-rights policies or procedures | 410-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | |

| Rights of Indigenous Peoples 2016 GRI 411 | Incidents of violations involving rights of indigenous peoples | 411-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | |

| Human Rights Assessment 2016 GRI 412 | Operations that have been subject to human rights reviews or impact assessments | 412-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | |

| Employee training on human-rights policies or procedures | 412-02 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Significant investment agreements and contracts that include human-rights clauses or that underwent human-rights screening | 412-03 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Local Communities 2016 GRI 413 | Operations with local community engagement, impact assessments, and development programs | 413-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | |

| Operations with significant actual and potential negative impacts on local communities | 413-02 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Supplier Social Assessment 2016 GRI 414 | New suppliers that were screened using social criteria | 414-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | |

| Negative social impacts in the supply chain and actions taken | 414-02 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Public Policy 2016 GRI 415 | Political contributions | 415-01 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | |

| Customer Health and Safety 2016 GRI 416 | Assessment of the health and safety impacts of product and service categories | 416-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | |

| Incidents of non-compliance concerning the health and safety impacts of products and services | 416-02 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Marketing and Labeling 2016 GRI 417 | Requirements for product and service information and labeling | 417-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | |

| Incidents of non-compliance concerning product and service information and labeling | 417-02 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | ||

| Incidents of non-compliance concerning marketing communications | 417-03 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ▪ | ||

| Customer Privacy 2016 GRI 418 | Substantiated complaints concerning breaches of customer privacy and losses of customer data | 418-01 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | |

| Socioeconomic Compliance 2016 GRI 419 | Non-compliance with laws and regulations in the social and economic area | 419-01 | ✔ | ▬ | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ▪ | |

| Company | Capacity (MW) | CSR Report | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vestas | 1657.6 | Yes | [73] |

| Enercon | 932.1 | No | [74] |

| Siemens Gamesa | 635.0 | Yes | [75] |

| Nordex | 188.8 | Yes | [76] |

| GE Renewable Energy | 238.2 | UNGC | [77] |

| GRI Standards | Disclosure | GRI Code | Vestas 2018 | Siemens Gamesa 2018 | Nordex 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foundation 2016 | 101 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| GENERAL DISCLOSURES 2016 GRI 102 | Organizational profile | Name of the organization | 102-1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Activities, brands, products and services | 102-2 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Location and headquarters | 102-3 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Location of operations | 102-4 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Ownership and legal form | 102-5 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Markets served | 102-6 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Scale of the organization | 102-7 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Information on employees and other workers | 102-8 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Supply chain | 102-9 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Significant changes to the organization and its supply chain | 102-10 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Precautionary principle or approach | 102-11 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| External initiatives | 102-12 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Membership of associations | 102-13 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Strategy | Statement from senior decision maker | 102-14 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Key impacts, risks, and opportunities | 102-15 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Ethics and integrity | Values, principles, standards, and norms of behavior | 102-16 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Location and headquarters | 102-17 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Governance | Mechanisms for advice and concerns about ethics | 102-18 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Governance structure | 102-19 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Delegating authority | 102-20 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Executive-level responsibility for economic, environmental, and social topics | 102-21 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Consulting stakeholders on economic, environmental, and social topics | 102-22 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Chair of the highest governance body | 102-23 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Nominating and selecting the highest governance body | 102-24 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Conflicts of interest | 102-25 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Role of highest governance body in setting purpose, values, and strategy | 102-26 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Collective knowledge of highest governance body | 102-27 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Evaluating the highest governance body’s performance | 102-28 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Identifying and managing economic, environmental, and social impacts | 102-29 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Effectiveness of risk-management processes | 102-30 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Review of economic, environmental and social issues | 102-31 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Highest governance body’s role in sustainability reporting | 102-32 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Communicating critical concerns | 102-33 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Nature and total number of critical concerns | 102-34 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Remuneration policies | 102-35 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Process for determining remuneration | 102-36 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Stakeholders’ involvement in remuneration | 102-37 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Annual total compensation ratio | 102-38 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Percentage increase in annual total compensation ratio | 102-39 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Stakeholder engagement | List of stakeholder groups | 102-40 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Collective bargaining agreements | 102-41 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Identifying and selecting stakeholders | 102-42 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Approach to stakeholder engagement | 102-43 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Key topics and concerns raised | 102-44 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Reporting practice | Entities included in the consolidated financial statements | 102-45 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Defining report content and topic boundaries | 102-46 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| List of material topics | 102-47 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Restatements of information | 102-48 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Changes in reporting | 102-49 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Reporting period | 102-50 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Date of most recent report | 102-51 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Reporting cycle | 102-52 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Contact point for questions regarding the report | 102-53 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Claims of reporting in accordance with the GRI Standards | 102-54 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| GRI content index | 102-55 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| External assurance | 102-56 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| MANAGEMENT APPROACH 2016 GRI 103 | Explanation of the material topic and its boundary | 103-1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| The management approach and its components | 103-2 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Evaluation of the management approach | 103-3 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| ECONOMIC STANDARD SERIES GRI 200 | Economic Performance 2016 GRI 201 | Direct economic value generated and distributed | 201-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Financial implications and other risks and opportunities due to climate change | 201-02 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Defined benefit plan obligations and other retirement plans | 201-03 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Financial assistance received from government | 201-04 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Market Presence 2016 GRI 202 | Ratios of standard entry-level wage by gender compared to local minimum wage | 202-01 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | |

| Proportion of senior management hired from the local community | 202-02 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Indirect Economic Impacts 2016 GRI 203 | Infrastructure investments and services supported | 203-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | |

| Significant indirect economic impacts | 203-02 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Procurement Practices 2016 GRI 204 | Proportion of spending on local suppliers | 204-01 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Anti-corruption 2016 GRI 205 | Operations assessed for risks related to corruption | 205-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Communication and training about anti-corruption policies and procedures | 205-02 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Confirmed incidents of corruption and actions taken | 205-03 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Anti-competitive Behavior 2016 GRI 206 | Legal actions for anti-competitive behavior, anti-trust, and monopoly practices | 206-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Tax 2019 GRI 207 | Approach to tax | 207-01 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | |

| Tax governance, control, and risk management | 207-02 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Stakeholder engagement and management of concerns related to tax | 207-03 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Country-by-country reporting | 207-04 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| ENVIRONMENTAL STANDARDS SERIES GRI 300 | Materials 2016 GRI 301 | Materials used by weight or volume | 301-01 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Recycled input materials used | 301-02 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Reclaimed products and their packaging materials | 301-03 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Energy 2016 GRI 302 | Energy consumption within the organization | 302-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Energy consumption outside of the organization | 302-02 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Energy intensity | 302-03 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Reduction in energy consumption | 302-04 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Reduction in energy requirements of products and services | 302-05 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Water and Effluents 2018 GRI 303 | Interactions with water as a shared resource | 303-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Management of water-discharge-related impacts | 303-02 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Water withdrawal | 303-03 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Water discharge | 303-04 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Water consumption | 303-05 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Biodiversity 2016 GRI 304 | Operational sites owned, leased, managed in, or adjacent to protected areas and areas of high biodiversity value outside protected areas | 304-01 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | |

| Significant impacts of activities, products, and services on biodiversity | 304-02 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Habitats protected or restored | 304-03 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| IUCN Red List species and national-conservation-listed species with habitats in areas affected by operations | 304-04 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Emissions 2016 GRI 305 | Direct (Scope 1) GHG emissions | 305-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Energy indirect (Scope 2) GHG emissions | 305-02 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Other indirect (Scope 3) GHG emissions | 305-03 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| GHG emission intensity | 305-04 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Reduction in GHG emissions | 305-05 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Emissions of ozone-depleting substances (ODS) | 305-06 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Nitrogen oxides (NOX), sulfur oxides (SOX), and other significant air emissions | 305-07 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Effluents and Waste 2016 GRI 306 | Water discharge by quality and destination | 306-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Waste by type and disposal method | 306-02 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Significant spills | 306-03 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Transport of hazardous waste | 306-04 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Water bodies affected by water discharges and/or runoff | 306-05 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Environmental Compliance 2016 GRI 307 | Non-compliance with environmental laws and regulations | 307-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Supplier Environmental Assessment 2016 GRI 308 | New suppliers that were screened using environmental criteria | 308-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | |

| Negative environmental impacts in the supply chain and actions taken | 308-02 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| SOCIAL STANDARDS SERIES GRI 400 | Employment 2016 GRI 401 | New employee hires and employee turnover | 401-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Benefits provided to full-time employees that are not provided to temporary or part-time employees | 401-02 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Parental leave | 401-03 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Labor/Management Relations 2016 GRI 402 | Minimum notice periods regarding operational changes | 402-01 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Occupational Health and Safety 2018 GRI 403 | Occupational health and safety management system | 403-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Hazard identification, risk assessment, and incident investigation | 403-02 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Occupational health services | 403-03 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Worker participation, consultation, and communication on occupational health and safety | 403-04 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Worker training on occupational health and safety | 403-05 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Promotion of worker health | 403-06 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Prevention and mitigation of occupational health and safety impacts directly linked to business relationships | 403-07 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Workers covered by an occupational health-and-safety management system | 403-08 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Work-related injuries | 403-09 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Work-related ill health | 403-10 | ▬ | ▬ | ▬ | ||

| Training and Education 2016 GRI 404 | Average hours of training per year per employee | 404-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Programs for upgrading employee skills and transition assistance programs | 404-02 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Percentage of employees receiving regular performance and career-development reviews | 404-03 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Diversity and Equal Opportunity 2016 GRI 405 | Diversity of governance bodies and employees | 405-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Ratio of basic salary and remuneration of women to men | 405-02 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Non-discrimination 2016 GRI 406 | Incidents of discrimination and corrective actions taken | 406-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Freedom of Association and Collective Bargaining 2016 GRI 407 | Operations and suppliers in which the right to freedom of association and collective bargaining may be at risk | 407-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Child Labor2016 GRI 408 | Operations and suppliers at significant risk for incidents of child labor | 408-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Forced or Compulsory Labor 2016 GRI 409 | Operations and suppliers at significant risk for incidents of forced or compulsory labor | 409-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Security Practices 2016 GRI 410 | Security personnel trained in human rights policies or procedures | 410-01 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | |

| Rights of Indigenous Peoples 2016 GRI 411 | Incidents of violations involving the rights of indigenous peoples | 411-01 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | |

| Human Rights Assessment 2016 GRI 412 | Operations that have been subject to human-rights reviews or impact assessments | 412-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | |

| Employee training on human-rights policies or procedures | 412-02 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Significant investment agreements and contracts that include human-rights clauses or that underwent human-rights screening | 412-03 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Local Communities 2016 GRI 413 | Operations with local community engagement, impact assessments, and development programs | 413-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Operations with significant actual and potential negative impacts on local communities | 413-02 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Supplier Social Assessment 2016 GRI 414 | New suppliers that were screened using social criteria | 414-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Negative social impacts in the supply chain and actions taken | 414-02 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Public Policy 2016 GRI 415 | Political contributions | 415-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Customer Health and Safety 2016 GRI 416 | Assessment of the health and safety impacts of product and service categories | 416-01 | ▬ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Incidents of non-compliance concerning the health-and-safety impacts of products and services | 416-02 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Marketing and Labeling 2016 GRI 417 | Requirements for product and service information and labeling | 417-01 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | |

| Incidents of non-compliance concerning product and service information and labeling | 417-02 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Incidents of non-compliance concerning marketing communications | 417-03 | ▬ | ✔ | ▬ | ||

| Customer Privacy 2016 GRI 418 | Substantiated complaints concerning breaches of customer privacy and losses of customer data | 418-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ▬ | |

| Socioeconomic Compliance 2016 GRI 419 | Non-compliance with laws and regulations in the social and economic area | 419-01 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mandilas, A.; Kourtidis, D.; Florou, G.; Valsamidis, S. A Framework for Sustainability Reporting of Renewable Energy Companies in Greece. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14360. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914360

Mandilas A, Kourtidis D, Florou G, Valsamidis S. A Framework for Sustainability Reporting of Renewable Energy Companies in Greece. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14360. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914360

Chicago/Turabian StyleMandilas, Athanasios, Dimitrios Kourtidis, Giannoula Florou, and Stavros Valsamidis. 2023. "A Framework for Sustainability Reporting of Renewable Energy Companies in Greece" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14360. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914360

APA StyleMandilas, A., Kourtidis, D., Florou, G., & Valsamidis, S. (2023). A Framework for Sustainability Reporting of Renewable Energy Companies in Greece. Sustainability, 15(19), 14360. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914360