1. Introduction

Gender encompasses various social characteristics, attitudes, and behaviors of women and men, which can be influenced by cross-cutting variables such as socio-cultural values, sex, race, religion, age, and ethnicity [

1,

2,

3]. Gender equality, in turn, is the condition where women and men have equal opportunities to enjoy their fundamental human rights and unlock their potential to contribute to human development [

1,

4]. Women’s empowerment is closely related to gender equality. It relates to women gaining power and control over their lives [

2], enabling them to access essential pillars of development, such as health, education, earning opportunities, rights, and political participation [

5]. However, despite progress toward gender equality and women’s development, women face various household and community constraints [

6]. Globally, 35% of women have experienced physical and/or sexual violence [

7], while approximately 750 million women or girls get married before age 18, and the global gender pay gap remains at 24 percent [

8,

9]. At the current rate of progress, achieving gender parity will take at least 108 years [

10]. These impediments can significantly hamper gender equality’s progress, making it vital to address them for women’s full participation in society.

The need for greater participation of all sectors of society in promoting gender equality is becoming increasingly urgent [

11]. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

12] provides an important foundation for strengthening global cooperation in this regard. The agenda specifically lists gender equality as its fifth sustainable development goal (SDG 5), which is accompanied by nine targets and fourteen indicators to track development on both local and global levels [

13,

14,

15]. The 2030 Agenda fosters gender parity and the transition to a world that is more equitable and sustainable by supporting institutional objectives.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development proposes gender-specific targets and indicators to achieve gender parity. To accomplish these goals effectively, developing short- and long-term measures is imperative. Considering there are not enough mechanisms to support that, this study aims to develop a comprehensive analysis of the gender-specific targets and indicators proposed by the 2030 Agenda to identify measures that bolster the achievement of gender equality in the private and public sectors. Additionally, it seeks to create a balanced scorecard (BSC) for gender equality encompassing all targets and indicators outlined by SDG 5. To achieve that, our key research question is: How to effectively translate gender equality (SDG 5) into operational terms through a strategic management system, to achieve sustainable development?

To achieve this study’s objectives, a comprehensive methodology will be conducted comprising a systematic literature review to identify and analyze the gender gender-specific targets and indicators proposed by the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, including a comprehensive and detailed literature review on prominent authors in the field of gender parity, business management, and sustainable development will be conducted. Additionally, a BSC will be proposed and developed considering all targets and indicators outlined by SDG 5, followed by a discussion on the managerial implications of implementing this tool for achieving gender equality. It is important to consider that the restructuring of the traditional architecture of the BSC will be needed to achieve the objective of this study by including new dimensions, guiding questions, and objectives that are not contemplated in the traditional version. Finally, a comprehensive strategy map will be constructed to illustrate the strategy and cause-and-effect relationships across the BSC for gender equality dimensions.

Compared to other published research, this study proposes a practical and effective tool for developing strategic skills and critical mechanisms in SDG 5 management at all levels. This can help organizations optimize their performance and re-evaluate their strategies toward gender equality. This study also allows decision makers and stakeholders to identify opportunities and areas for improvement in gender parity. Additionally, the proposed strategy map facilitates communication between different teams and sectors, aligning expectations and promoting a culture of learning and growth, and shared responsibility among decision makers and executors, reinforcing the strategic importance of gender equality. This study contributes to the literature by combining gender equality management with the BSC, which has not been widely explored in previous studies providing a comprehensive and integrated framework for organizations to effectively monitor and evaluate their performance and make strategic decisions that align with their goals and values. In summary, this study adds value to the subject area of sustainable development goals management and strategic decision making by proposing a practical tool and framework for strategic decision-making measures through the BSC, which can apply to other goals proposed by the 2030 Agenda.

The main contribution of this study is related to the proposition of a strategic management tool that proposed an effective way to create and develop strategic skills and key mechanisms through the management and implementation of SDG 5 at all levels, helping organizations to optimize performance and re-evaluate their strategies for this purpose. It also offers decision makers and stakeholders to identify opportunities and points for improvement. Finally, developing a strategic map facilitates communication among teams and different sectors, aligning expectations and stimulating a culture of learning and growth. It also helps stakeholders understand how their work fits the broader picture, promoting collaboration towards common goals. It also encourages a dynamic and adaptable organization that can navigate challenges more effectively.

In summary, this study addresses a particular gap in the literature by suggesting a valuable and efficient tool for enhancing strategic skills as well as critical mechanisms for achieving SDG 5 at all levels. By combining gender equality with a managerial perspective and the BSC, this study contributes to the literature by offering organizations an in-depth and integrated framework for efficiently tracking and assessing their performance while making strategic decisions aligned with their objectives and values.

2. Literature Review

The 2030 Agenda proposes 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs), which serve as crucial guidelines for the accomplishment of sustainable development by 2030. Additionally, the document declares that promoting gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls is essential to achieving progress across all goals and targets. Therefore, it provides a set of gender equality targets and indicators. Furthermore, this section is committed to analyzing the cross-cutting elements embedded within SDG 5 to follow up on its current rate of progress and it examines SDG 5 targets and indicators.

Table 1 presents the nine goals that will be discussed here, pairing them with the authors brought to the discussion.

Table 1 plays an essential role in our research by providing a thorough list of all SDG 5 targets, facilitating a concise understanding of the scope of these goals. Additionally, it offers readers a helpful starting point to identify pertinent authors and studies that address these goals and add to the ongoing academic discussion about the impact of gender equality on sustainable development. By utilizing

Table 1, we can effectively structure the debate that unfolds in the subsequent sections of our research. This strategy allows us to incorporate the findings from our research with the broader literature, leading to a more in-depth and accurate discussion of the potential and challenges associated with meeting SDG 5 targets. Besides, a literature review on the topics of women’s full participation in decision making, universal access to sexual and reproductive health, equal rights to economic resources for women, empowering women through technology, and gender equality promotion through policies and legislation is essential to gain a comprehensive understanding of the current state of these critical issues. These topics are correlated and critical to achieving gender equality and women’s empowerment globally. A literature review on each of these topics can inform the development of evidence-based policies and interventions that can effectively address the gender gap in these areas.

2.1. Sustainable Development Goal 5: Gender Equality

Discrimination against women and girls is a pervasive global issue [

9]. Despite international efforts to address this issue, gender discriminatory laws persist, impeding women’s ability to enjoy their fundamental human rights [

12,

16,

17,

18]. To bridge the current gender gap, agents of change, such as society, governments, and organizations, need a holistic and strategic tool to address gender disparities effectively. However, there is a lack of a specific management system designed to achieve this objective. To develop an effective approach, it is essential to analyze and comprehend the various situations that impede women’s development, which will be discussed in further detail below.

2.1.1. Discrimination and Violence against Women and Girls

Worldwide, approximately 35% of women have suffered some form of violence against women (VAW) [

26,

27]. Available comparable data show that women comprise the majority of victims of Intimate Partner Violence (IPVs) when compared to men [

9]. Additionally, 7% of females experienced non-partner sexual violence globally, being abused and forced to perform sexual acts by someone other than an intimate partner [

26,

28]. VAW severely impacts women’s health and empowerment; it increases females’ risks of becoming infected with STIs, having unwanted pregnancies, and developing psychological disorders, such as substance abuse, depression, and suicidal behaviors [

26,

29,

30]. Hence, adequate treatment must be in place to support the recovery of these victims. Investments in multi-sectoral services and critical infrastructures are a few examples of essential initiatives toward that end [

26].

Furthermore, studies show that VAW often coexists in settings where other forms of violence prevail. For instance, higher rates of non-partner sexual abuse are prevalent in Namibia, where violence and childhood sexual abuse commonly occur [

26]. In this context, gender training and community-based initiatives are critical mechanisms to enhance local knowledge sharing and develop life skills for gender equality [

31].

Additionally, effective responses for VAW, such as fundraising and grant-making mechanisms must be encompassed into broader national development plans and States’ budgets, supporting gender budgeting and resource allocation within the governmental structure incorporating a gender perspective at all levels of the budgetary process and restructuring revenues and expenditures in order to promote gender equality [

23].

2.1.2. Harmful Practices against Women and Girls

Harmful practices against women and girls, such as child, early, and forced marriage, and female genital mutilation, remain prevalent and are a significant barrier to achieving gender equality and women’s empowerment. Although early marriage rates have declined over the past decades, according to the latest data, approximately 650 million women and girls alive today were married before the age of 18 [

33]. Therefore, to eliminate this practice by 2030, it is crucial to conduct additional efforts, and education mechanisms are an excellent place to start. For instance, the Egyptian Ishraq program empowers poor out-of-school girls by developing their literacy, life, and money management skills [

34]. These initiatives enhance women’s knowledge enhancement and develop critical skills to overcome entrenched gender barriers [

35]. Furthermore, many women still face female genital mutilation (FGM). Globally, approximately 200 million girls have undergone FGM procedures, which comprise partial or total removal of the female external genitalia or other injuries to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons [

36,

37]. FGM rates have been decreasing over the last three decades, particularly in Kenya, Ethiopia, and Liberia [

37]. Despite these advances, FGM still prevails in other countries such as Guinea, Djibouti, Sierra Leone, and Mali [

37]. The worldwide criminalization of FGM is urgent; otherwise, population growth will inevitably raise the contingent of its victims [

38].

2.1.3. Sexual and Other Types of Exploitation

Marital rape is another serious offense, predominantly experienced by women, that occurs whenever spouses or dating partners do not consent to sexual intercourse [

21]. Currently, at least 49 countries (e.g., Tanzania, Malawi, Bahrain) exempt perpetrators from being penalized for this aggression, and therefore violate women’s fundamental rights and freedoms [

8,

20,

22]. Legal frameworks reflect States’ stance towards women’s rights; therefore, it is vital to strengthen legal frameworks that promote, enforce, and monitor equality and non-discrimination based on sex as well as to rely on fundraising and strategic partnerships among stakeholders [

9,

12,

19,

23,

24]. Governments have the power to create an enabling environment for women’s access to justice [

9]. For example, Brazil has enacted the Maria da Penha Law, establishing effective measures to prosecute and convict perpetrators of domestic violence, while assisting domestic violence victims by implementing specialized courts, shelters, and police stations [

25].

2.1.4. Recognizing the Value of Unpaid Care and Domestic Work

Worldwide, women perform 2.6 fold the unpaid care and domestic work than men [

9]. Studies indicate that females contribute up to 76.4% of total unpaid care work, whereas men contribute to hardly 36.1% of total paid work [

40]. Women’s contribution to unpaid care work in emerging countries is the highest (80.1%), followed by developing countries (74.9%) and developed countries (65.6%) [

40]. This unbalanced devotion to unpaid care and domestic work hinders women’s full-time dedication to education, political participation, and income-generating activities, which are potent constituents for gender equality [

41,

42].

Public policies and comprehensive programs must be in place; otherwise, women cannot access equal economic opportunities [

9,

43]. Today, there are prominent tools to reduce females’ double burden and support the homogeneous distribution of household tasks including social programs, accessible early childhood education and childcare, paid family leave, universal old-age pensions, and healthcare programs [

9,

43,

44,

45]. Another vital aspect is to develop women’s skills to engage in paid work through adequate training [

25]. Awareness-raising and skills programs, for instance, drive capacity building and promote women’s leadership, entrepreneurship, critical thinking, and money management skills [

46,

74]. They empower women to develop a fundamental skill set to mobilize for social transformation, access higher-productivity jobs, and leadership positions [

25].

2.1.5. Women’s Full Participation in Decision-Making Processes

Women remain underrepresented in political, economic, and public life. Worldwide, women hold approximately 24% of parliamentary seats; considering country levels, Rwanda occupies the leading global position, where 61,3% of women occupy seats on the country’s national parliament, and 53.2% of females hold seats in the lower house [

27,

75]. Despite that, progress has been made. In 2018, female representation rates reached an average of 30% in the Americas, both in the lower and upper chambers [

49]. Gender parity reforms played a crucial role in achieving that milestone. In Latin America, for instance, the establishment of electoral gender quotas has proven to effectively increase female political representation [

9]. Additionally, after Costa Rica introduced the gender parity reform in 2014, the share of women parliamentarians raised from 33.3 percent in that year to 45.6 percent in 2018 [

49].

Studies confirm that female participation enhances companies’ stock prices and profits [

51]. Notwithstanding, women’s underrepresentation is also prevalent, while only 36 women are likely to hold leadership positions as legislators, senior officials, and managers for every 100 men [

25].

In 2018, women entailed 39% of the global workforce; nonetheless, only 27% of females held managerial positions worldwide [

27]. In the past decade, Iceland, Cyprus, Sweden, and Austria, have had a substantial increase (6%) of women occupying middle and senior and managerial positions; nonetheless, the proportion of women in senior and middle managerial positions remains below 50 percent in all countries, except in the Dominican Republic, where female executive participation reached nearly 53 percent in 2015 [

9,

50].

Societal, structural, and hierarchical barriers reduce women’s ability to access middle and senior managerial positions [

51,

52]. The “glass ceiling” phenomenon prevents women from accessing higher-level decision-making management positions, regardless of their merits [

53,

54]. Accordingly, the introduction of gender quotas in company boards has been an effective response to bridging the gender gap in the private sector [

25].

2.1.6. Universal Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights

Approximately 4.3 billion people of reproductive age will lack access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights (SRHR) at some point in their lives, due to gender inequalities, inadequate resources, lack of critical infrastructures, and political will [

55]. Women tend to have more access to SRHR in countries where gender parity rates are higher [

26]. Hence, monitoring the proportion of women and girls who make autonomous and informed decisions on reproductive health is an important measure to track the progress of gender equality [

27].

Every year, approximately 225 million women of reproductive age have an unmet need for modern contraception, 74 million women have undesired pregnancies, and more than 500 thousand women suffer from health complications connected to pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period [

56]. Besides, available comparable data from 51 countries shows that only 57% of women aged 15 to 49 who are married or in a union make their own decisions about sexual relations and the use of contraceptives and reproductive health services [

27]. These data sets externalize the prevailing suppression of women’s sexual autonomy due to unbalanced gender roles, lack of public assistance, investments, and comprehensive frameworks.

Furthermore, several customary and gender-biased laws circumscribe women’s sexual autonomy. Of 186 countries, 19% limit women’s universal access to contraception, through age, parental consent, and marital status restrictions [

57]. Besides, existing marriage laws often regulate females’ sexuality and bodily integrity, mostly by imposing restrictions such as age limitations, marital status conditions, and third-party authorization requirements [

9,

21]. Most countries also have restrictive abortion laws, which increase unsafe or illegal abortion rates, provoking harmful consequences to women’s health [

55].

To tackle SRHR challenges, it is vital to call for a global commitment to reinforce national laws and policies to safeguard and fulfill universal access to SRHR rights [

58,

59]. Aside from the legal benefits, comprehensive laws foster knowledge sharing, and awareness-raising concerning sexual education, family planning, and sexual health, promoting the prevention of unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortions and also reducing maternal and child mortality [

9,

19,

60].

2.1.7. Equal Rights to Economic Resources for Women

Globally, nine in ten countries have laws impeding women’s economic opportunities [

6]. Access to land, natural resources, and other forms of property, such as land ownership, increases individuals’ ability to engage in income-generation activities, driving economic empowerment [

9]. Thus, women’s access, ownership, and control over agricultural land expand their negotiating power, enhancing their ability to address social and economic vulnerability [

61].

Females are deeply engaged in the agricultural labor force (43%); however, they own less than 15% of the global land and are less likely than men to hold a legal document proving their entitlement to land ownership [

62,

63].

Women’s ability to control essential assets contributes to global economic growth [

9,

64]. If women had the same access to productive resources as men, especially in rural areas, agriculture production would increase, and the number of the hungry population would decline by 100–150 million.

Women’s limited access to land rights is often connected to institutional, economic, and cultural constraints, which deny their equitable access to economic resources [

61]. In Rwanda, for instance, females have limited control over family assets, lack political representation, and account for only 26% of sole landowners.

Laws that guarantee equal land rights and the review of unbalanced land policies represent crucial efforts to address women’s equitable access to economic resources [

64,

65]. For example, Rwanda’s Matrimonial Regimes, Liberties and Succession Law of 2000 reached a milestone, recognizing, for the first time, women’s and girls’ rights to inherit land property in the country [

66].

Despite current efforts, many countries still hold discriminatory frameworks that prevent females’ access to land rights [

67]. Most customary tenure systems in Africa tend to favor men over women, granting females land rights solely through a husband or male relative [

63]. Besides, the use of customary law in the occasion of separation, divorce, or annulment of marriage also challenges the equitable sharing of property between women and men within the region [

66].

Gender-responsive laws are not sufficient to secure women’s access to land rights, mostly because law enforcement relies upon changes in behaviors, attitudes, and practices [

12]. In this sense, capacity-building in women’s rights and gender mainstreaming for land administration and tenure institutions is an important mechanism that bolsters internal commitment to the provision of equitable land ownership frameworks [

66].

2.1.8. Empowering Women through Technology Enablement

Information and communications technology (ICT) advances gender equality and women empowerment, however, despite ICT’s benefits, the proportion of women using the internet globally was 5.9 percentage points lower than men’s [

9].

Mobile phone networks and mobile-cellular subscriptions have drastically risen in the last decade, increasing empowerment rates, and productivity growth, and allowing marginalized communities to become more interconnected than ever before [

68,

69]. Nonetheless, females still lag behind men regarding mobile phone ownership [

9]. Globally, 327 million fewer women than men own a smartphone and can freely access the mobile Internet, while women from low and middle-income countries are 10% less likely to buy a mobile phone when compared to men [

68,

70]. Digital inclusion increases women’s opportunity to develop essential digital communication, and problem-solving skills [

71]. However, it requires critical infrastructure, funding, stakeholders collaboration, access to education and digital literacy, online/offline safety, and security practices [

71].

Digital solutions also promote access to knowledge and opportunities, reducing gender barriers [

25]. Mobile-based emergency services, access to 24/7 online, and confidential chat services have proven to support VAW victims [

24,

25,

72]. Furthermore, ICTs have raised awareness over authoritarian practices and discriminatory frameworks in Iran, increasing knowledge-sharing among women and men [

73].

2.1.9. Gender Equality Promotion through Policies and Legislation

Gender mainstreaming is the process of assessing the gender implications of any planned action, and promoting the integration of gender equality into legislation, policies, budgets, and programs [

2]. Therefore, it is a fundamental strategy for achieving gender equality. The 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform of Action coined the principle of adequate financing for gender equality. It infers that governments must conduct systematic efforts to track public sector expenditures and ensure responsive resource allocations for gender equality [

17].

Embedding gender equality measures into strategic planning and budgeting promotes equitable policies and legislation [

69]. Governments that establish a comprehensive system and publicize gender equality allocations reinforce transparency and accountability [

9]. Therefore, it is essential to monitor the proportion of countries with systems to track and make federal allocations for gender equality and women’s empowerment (Indicator 5.c.1) [

13].

Gender budgeting fosters the identification of overarching gender equality goals towards which resources can be directed [

74]. Moreover, the implementation of gender-responsive financing mechanisms drives changes in culture and therefore requires strong political commitment [

74]. The 2018 Canadian Gender Results Framework, for instance, tracks gender-equality indicators performance, and identifies significant gender gaps, fostering adequate financing and gender-budgeting within the country [

74].

Underinvestment and inadequate financing on critical areas of concern limit the adoption of relevant policies and legislation, ultimately hampering the progress of gender equality [

69]. In 2018, of 69 countries, only 19% developed a comprehensive system to track budget allocations for gender equality [

27].

3. The BSC Approach: Structure and Concepts

The BSC is a management tool developed by Robert Kaplan and David Norton to balance financial and non-financial organizational performance measures. It incorporates four perspectives: financial, customer, internal processes, and learning and growth, and translates an organization’s mission and strategy into a set of performance measures, providing a framework for strategic measurement and management [

76]. The Financial Perspective is the first dimension and a crucial element of the BSC, as it must be linked to the company’s strategy and form a chain of cause-and-effect relationships that significantly improve financial performance. It also represents a strategic theme for the business unit, emphasizing the importance of financial metrics in achieving strategic objectives. It should not be a set of isolated, disconnected, or even conflicting goals. To effectively communicate the strategy, the story must be told, beginning with long-term financial objectives and linking them to the required sequence of actions for financial processes, customers, internal processes, employees, and systems to achieve desired economic performance over the long term [

76].

The second dimension, the Customer Perspective, is also an essential element of the BSC. It helps organizations identify the customer segments and markets they want to target, ultimately producing the revenue for the company’s financial goals. This perspective aligns the essential measures of customer-related outcomes with specific customer and market segments, allowing for the precise identification and evaluation of value propositions aimed at these segments. Value propositions are trend vectors and indicators for crucial outcome measures from the customer’s perspective. In addition to satisfying and delighting customers, executives should translate their strategic mission statements into specific market and customer-based objectives from this perspective. This will help organizations better understand customer needs and preferences, improving customer satisfaction and ultimately increasing revenue [

76].

Thirdly, the Internal Processes Perspective aims to identify critical points along the entire internal value chain of the company, starting with identifying customers’ current and future needs and developing new solutions based on those findings. It is important to analyze and detect how the process of delivering products and providing services to existing customers is going and also analyze the after-sales services that complement the value provided to customers. In today’s business environment, measuring the performance of cross-functional and integrated business processes that cut across multiple organizational departments is increasingly essential. This represents a significant improvement over existing performance measurement systems. Therefore, companies must prioritize this perspective to ensure efficiency, effectiveness, and customer satisfaction in their internal processes [

76].

Finally, the fourth perspective is Learning and Growth. After developing objectives and measures for the previous perspectives, guiding the objectives and measures for organizational learning and growth. These goals provide the infrastructure that enables the achievement of goals established in the previous perspectives.

The traditional BSC embeds financial and non-financial indicators within its objectives and measures; despite that, its long-term purpose is to achieve financial success [

77]. Therefore, the shareholder’s perspective is placed at the top of the scorecard’s hierarchy, followed by the customer, internal processes, and learning and growth perspectives [

78,

79]. A cause-and-effect chain pervades all BSC perspectives and indicates how their metrics and objectives intertwine (

Figure 1). Hence, relevant actions must be implemented across all these perspectives to achieve organizations’ objectives [

77].

The development of the BSC has sparked a significant amount of academic debate and research. The

Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change dedicated two special editions to works on the BSC, and numerous studies with literature reviews have been published on the topic. These contributions demonstrate the relevance and timeliness of the BSC, both in the “real world” and the academic world. An effective BSC translates the necessary measures and tools for organizational learning and growth into innovative and effective strategies for internal business processes, creating value for customers and shareholders’ financial success [

11,

76,

80]. In addition, after the BSC was introduced, researchers realized the importance of illustrating the cause-and-effect relationships across the scorecard, which led to the creation of the strategy map [

81]. This map provides a detailed illustration of an organization’s strategies and translates intangible assets into tangible outcomes for balanced strategy execution [

78,

81].

The strategy map is a critical tool in the BSC framework, as it allows organizations to decode complex strategic planning processes and translate them into specific objectives and actions. The strategic map is based on three essential assumptions: cause-and-effect relationships, performance vectors, and the relationship with financial factors. These assumptions are aimed at ensuring that the strategic objectives are interconnected and aligned toward achieving the overall organizational goals. Furthermore, the BSC assumes that incomplete strategies cannot produce the desired results for the organization [

82]. As such, the strategic map serves as a “normative checklist” for a strategy’s components and interrelationships. If a strategy is missing an element on the strategy map template, it is likely to be flawed and may not lead to the desired outcomes [

81].

The traditional BSC can be customized to meet organizations’ specific demands [

77]. For instance, government organizations, non-profit, and public sector enterprises (NPSEs) can create a personalized scorecard to promote sustainable development for their constituents [

83]. In this context, several authors advocate for extending the BSC to sustainability and sustainable development [

84,

85,

86].

The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard (SBSC) is a powerful strategic tool that helps organizations monitor and achieve sustainability objectives in the private and public sectors [

84,

85,

87]. It has been widely adopted across industries, and research indicates that it can be instrumental in driving positive outcomes for sustainable development [

84]. The primary objective of an SBSC is to achieve sustainability, which requires integrating sustainability-oriented goals into the organization’s strategic planning process, placing non-financial perspectives at the top of the hierarchy, and incorporating new perspectives into the scorecard [

11,

84,

88]. Unlike the traditional BSC, the SBSC’s cause-and-effect chain is designed to integrate financial measures with environmental, social, and economic goals for sustainable development [

84,

89]. Using the SBSC, organizations can effectively measure and manage their environmental and social impact, which is critical for achieving long-term success and contributing to the global sustainability agenda.

Hence, it is evident that a comprehensive approach is necessary to address the challenges of gender equality and sustainable development. This requires the definition of multiple perspectives, new methods of performance measurement, and the identification of variables and indicators that can contribute to enhancing the strategic management system. By adopting such an approach, decision makers can significantly improve the quality of management and lead the way toward sustainable development while promoting gender equality, as advocated by SDG 5. Therefore, it is plausible to assume that strategic management systems, such as the BSC, can play a crucial role in this process, provided they are appropriately applied and adapted to promote gender equality.

The BSC has emerged as a valuable framework to support sustainable development strategies at the organizational and societal levels, as evidenced by numerous studies [

11,

84,

85,

86]. Given that gender equality is a cornerstone of a sustainable society, the authors of this study propose a BSC specifically redesigned to advance Gender Equality for Sustainable Development. In developing the BSC, the authors used SDG 5 as a strategic guide but also drew on a critical literature review to identify additional short- and long-term measures beyond those proposed by SDG 5. These measures, mainly related to the financial and key mechanisms perspectives, were integrated into the BSC’s structure and depicted in the cause-and-effect relationships illustrated in the strategy map. The resulting BSC for Gender Equality for Sustainable Development provides a comprehensive and customized framework that can help organizations effectively manage gender equality issues and contribute to achieving sustainable.

4. Methodological Procedures

The following explanation summarizes the methodology applied to this paper’s development. First, given the prominence of the UN SDGs and considering that the 2030 Agenda sets credible targets and indicators towards sustainable development, the authors opted to use the specific measures embedded within SDG 5 as strategic guidelines for the construction of the BSC.

An extensive literature review was conducted in regard to SDG 5 targets and indicators to analyze strategic measures and identify important mechanisms for gender equality and sustainable development. The literature review was based on articles collected from scientific databases, including Science Direct, Scopus, and Web of Science, and demonstrates the nexus between gender parity and sustainable development, grounding the construction of the BSC toward that end.

After, the BSC architecture was adapted to meet gender equality strategies [

77]. Then, the traditional BSC perspectives were renamed and adjusted according to the new content [

82]. Additionally, guiding questions were designed to depict the cause-and-effect relationships across the BSC strategic objectives and perspectives.

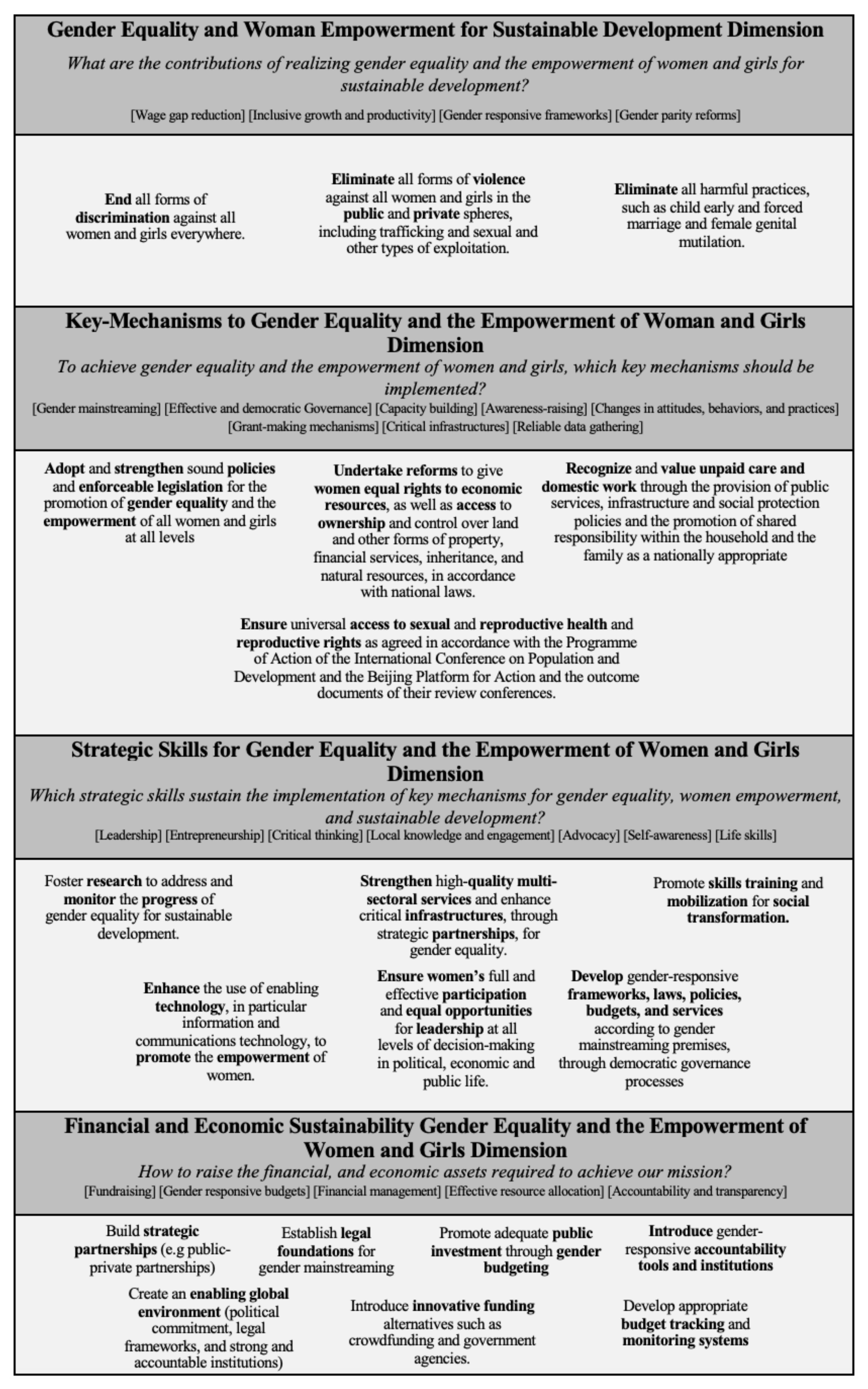

Figure 2 portrays these adaptations.

Redesigning the BSC framework is a smart strategy for organizations looking to promote gender equality and sustainable development in their communities and beyond. The gender-reshaped BSC framework presented in this research offers organizations a clear roadmap for modifying their conventional BSC structure to support gender equality objectives. With this meticulous framework, organizations can align their vision and mission with their strategic goals, effectively targeting, tracking and assessing their performance on gender equality. By doing so, they can make significant strides toward building a more equitable and sustainable future for all.

The next step was the construction of a strategy map to provide a graphic overview and illustrate the cause-and-effect relationships of the BSC. This proposal followed a top-down process, as recommended by [

81], to translate the BSC long-term goal (gender equality) into specific strategies, strategic themes, and objectives.

Initially, according to the literature review, the authors unfolded the new scorecard’s perspectives into strategic themes and strategic objectives, to add a second layer of detail to the BSC [

81]. After analyzing critical mechanisms, and skills for gender equality and sustainable development, 21 strategic objectives and 24 themes were identified and incorporated into the strategy map structure. The incorporation of these features provides immediate visualization of the strategy and allows decision makers to visualize the strategy and take action in real-time.

A search was carried out in the Web of Science database, collecting 931 articles for analysis, limited to the period from 1992 to 2019. The main results indicate that the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) was addressed in 15 different areas, with emphasis on Public Administration and Industry. The case study technique was the most used to illustrate the application of the tool. Regarding the objectives of the articles, 39.13% aimed to analyze the application of the BSC in organizations, while 20.29% evaluated its feasibility of implementation and another 20.29% contributed to the existing literature on the subject. With regard to organizational spheres, private companies were the most studied, totaling 49.28% of the articles collected. Other bibliometric studies on the subject were carried out using databases such as the ISI database, Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), Web of Science, Scielo, and SPELL. Numerous authors have already conducted relevant research in this area; however, these studies were restricted to analysis periods of up to 20 years, not covering the 28 years of existence of the literature on the subject [

90,

91,

92]. This new layer of detail contributes to identifying the cause-and-effect relationship across the strategy map, as shown in

Figure 1. After proposing a BSC for gender equality (

Figure 2), and structuring the strategy map (

Figure 3), the cause-and-effect relationships across the strategy maps were defined.

Figure 4 illustrates the strategy map of a BSC for Gender Equality.

In order to present an overview, the steps taken to adapt the BSC to the research objective are presented, as shown in

Figure 3.

To effectively adapt the BSC to a gender equality approach, conducting a comprehensive review of the literature and aligning the structure with the support systems in place for companies and organizations was crucial. This thorough adaptation process has resulted in a redesigned BSC model that is well equipped to promote gender equality and contribute to its achievement. By adopting this model, organizations can ensure that their strategies are inclusive and equitable, leading to greater success and sustainable development.

5. Results: The Proposal of a BSC for Gender Equality

5.1. Gender Equality Initiatives for Sustainable Development

To develop a comprehensive BSC model for gender equality, the authors conducted a detailed analysis of gender-specific initiatives that work across all three pillars of sustainable development—economic, social, and environmental—in addition to considering SDG 5 parameters and conducting a thorough literature review. The results of this analysis are presented in

Table 1 and provide valuable insights into the measures, skills, and mechanisms necessary to achieve gender equality. These insights were then translated into operational terms and incorporated into the strategy map (

Figure 4). Therefore, this approach not only considers the broad goals of gender equality but also provides practical and actionable steps to achieve it. The following analysis breaks down prominent initiatives found across the literature review (

Table 1) that hone and accelerate progress to realizing gender equality for sustainable development.

Table 2 in this study plays a crucial role in demonstrating the various evidence-based activities that can be undertaken to advance gender equality and women’s empowerment. The table highlights specific measures that organizations and policy makers can take to ensure that gender equality is integrated into their strategic plans and operations. By providing concrete examples of initiatives, such as offering equal pay for equal work or implementing gender-sensitive budgeting, the table is a practical guide for those seeking to advance gender equity.

Additionally, the table’s recommendations are based on a thorough literature review, indicating that the proposed measures have a solid evidence base and are likely to be effective. Policy makers and stakeholders can use this table to identify areas where their organizations or policies may be falling short and take steps to address these gaps. Overall,

Table 2 is a valuable resource for promoting gender equality, empowering women and girls, and ensuring that organizations and policies are aligned with SDG 5. By following the guidelines.

Advancing Gender Equality through Comprehensive Initiatives

Gender equality is a critical component of sustainable development, as it promotes women’s access to development’s basic constituents and creates an enabling environment for safeguarding their rights. However, achieving gender parity is a complex task that requires actions in various sectors, such as implementing transparency tools, establishing gender-responsive institutions, and mobilizing for social transformation [

9,

27,

69]. Political commitment is also crucial to foster responsive legal frameworks, accountable institutions, and investments that enable women’s empowerment [

9].

Mobilizing for social transformation requires addressing imbalanced behaviors, attitudes, practices, and gender stereotypes [

12]. The Tostan International Community Empowerment Program (CEP) is an example of a community-based initiative that supported the elimination of female genital mutilation in approximately 8000 communities in eight African countries. Creating a comprehensive and representative system to overcome women’s political underrepresentation and lack of economic opportunities is also crucial, and initiatives such as inclusive and specific policies, programs, and temporary special measures (TSMs) that bolster local knowledge sharing, awareness-raising, and changes in discriminatory behaviors, can help achieve this goal [

9,

90].

Additionally, to achieve gender equality, creating a comprehensive and representative system that addresses women’s political underrepresentation and lack of economic opportunities is essential. Female participation in decision making is crucial for effective and democratic governance, as it brings new perspectives and concerns to political agendas [

49]. Inclusive policies, programs, and temporary special measures (TSMs), such as gender quotas have been proven effective in promoting gender balance in decision making in public and private spheres [

9,

10,

28,

89]. Countries such as Norway, Iceland, Sweden, and Italy have implemented gender quotas in state-owned companies, promoting female political representation and integrating gender issues within the labor market. These efforts promote women as a role models, promote female political representation, and integrate gender issues within the labor market, ensuring women’s access to equitable opportunities for leadership in political, economic, and public life [

9,

10,

43,

97].

Besides political underrepresentation, women still face significant economic inequalities. The gender pay gap persists, and women are more likely to be unemployed than men, regardless of their age [

54,

66]. Women also shoulder the majority of household duties and childcare responsibilities, which limits their economic opportunities [

5,

8,

25]. It is crucial to implement measures that address these disparities, such as public policies and social programs, to ensure women’s access to equal economic opportunities.

For example, closing the gender gap in mobile ownership and mobile internet and could lead to substantial economic benefits. Adequate and sustained investments in technology and infrastructure can enhance women’s access to enabling technology, improve their participation in the digital society, and increase their labor-force participation by enhancing their labor quality, skills, and education. These improvements can bolster female employment rates in high-productivity sectors and leadership roles, leading to gender equality, economic development, and growth [

24,

25]. Therefore, it is crucial to prioritize investments in technology and infrastructure to reduce the gender gap in mobile ownership and mobile internet access.

Investments in strategic partnerships and gender budgeting are also essential to enhance universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights. These initiatives could lead to the elimination of all forms of violence against women and girls in public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation. Providing adequate treatments to victims of violence against women leads to improved self-awareness and communication skills [

9,

12,

19,

23,

24].

Recent accomplishments, such as the banning of FGM in Sudan, were only achieved through the combination of actionable initiatives, including advocacy efforts, community-based initiatives, and gender-neutral frameworks. Furthermore, universal access to SHRS requires investments in multidisciplinary and gender-sensitive measures, health system resilience, and multi-sectoral services [

23,

24,

61].

Regarding legal and governance frameworks, the lack of gender mainstreaming can result in the inability to achieve gender equality, including equal access to economic resources such as property ownership, financial services, and natural resources. Additionally, the absence of gender-responsive policies, budgets, and benefits can hinder progress toward eliminating discrimination against women and girls at all levels. Thus, a holistic approach to addressing discriminatory behaviors by integrating gender-responsive frameworks, budgeting initiatives, capacity-building programs, and advocacy efforts is necessary to achieve gender parity [

12,

66]. This study provides evidence supporting the combination of these initiatives, including community-based initiatives and gender-neutral frameworks, to harness women’s leadership, develop self-awareness, and enhance life skills for engagement in public life. The results call for integrating these initiatives (

Table 2) into the strategy map (

Figure 4) to promote gender equality and women’s empowerment.

5.2. Proposing a Strategy Map for Gender Equality and Sustainable Development

This study proposes a strategy map for implementing actionable measures to enhance strategy execution toward gender equality within public and private institutions [

81]. The following strategy map translates the BSC perspectives and guiding questions (

Figure 2) into a visual framework providing immediate visualization of a strategy supporting decision makers and stakeholders to test business hypotheses, identify opportunities, and evaluate performance in real-time.

Figure 4 illustrates this study’s proposal for a strategy map for gender equality and sustainable development. It includes hypotheses and methods based on literature review finding for achieving gender equality within private and public institutions.

Besides depicting the BSC into a visual framework, the authors also test the BSC strategic objectives and initiatives assembled in

Table 1 to validate and confirm the cause-and-effect relationship across the strategy map to endorse its applicability for gender equality and sustainable development [

81].

The proposed strategy map (

Figure 4) is an essential tool for organizations to align their strategic goals with the ideals of gender equality. By utilizing this framework, organizations can monitor and evaluate their performance in achieving gender-equality objectives and support promoting sustainable development and gender equality in their communities and beyond. The strategy map provides a clear path for organizations to follow, enabling them to adapt their strategic goals and mission to incorporate gender equality effectively. By implementing this map, organizations can contribute to the elimination of gender discrimination and empower women and girls at all levels, ultimately promoting a sustainable and equal society.

As shown in

Figure 5, the relationships between sustainability and the BSC are considered adequate [

79,

88], and the connection between them with gender equality.

The proposed BSC and strategy map for gender equality offer a practical and adaptable framework that facilitates strategic planning and contribute to achieving sustainable progress toward gender equality and the SDGs. As demonstrated by the literature review, the BSC framework has been successfully applied to promote sustainability measures across various organizations [

11,

79,

84,

88]. However, to date, there has been a lack of a practical gender equality framework applicable to private and public organizations and government institutions.

The proposed strategy map creates opportunities for raising economic assets, developing strategic skills, and implementing key mechanisms for gender equality. It provides a practical guideline for monitoring progress at all levels and helps organizations to optimize performance and re-evaluate strategies toward the BSC’s overarching goal. Including specific metrics, goals, and targets allows for effective tracking and monitoring within a business unit, making it a powerful tool for implementing actionable strategies across institutions.

In addition, the strategy map promotes communication across different teams and sectors, aligning expectations between creating and operationalizing strategy for gender equality. It also provides a visual overview of gender equality and sustainable development goals, facilitating strategy execution and verification.

Ultimately, the strategy map’s adaptability and holistic approach enable private and public organizations and government institutions to apply the framework to promote and monitor short- and long-term measures toward sustainable progress for gender equality and the SDGs. By utilizing the BSC’s features for gender equality, decision makers and stakeholders can identify opportunities and weaknesses, track progress, and monitor initiatives for achieving the BSC’s goal faster. Overall, the proposed strategy map can stimulate a learning and growth culture among decision makers and executors, significantly contributing to sustainable development by 2030. Accordingly, private and public organizations and government institutions can apply this study’s framework to promote and monitor short-term and long-term measures.

6. Discussion

Proper use of the proposed strategic map highlights the search for gender equity, which can be quantified as suggested by the authors, representing a commitment to stakeholders. The strategy map can be enhanced to further think about achieving the SDGs in relation to gender equality.

In addition, the strategic map is important for converting the defined strategy into specific objectives, indicators, goals, initiatives, and budgets. Based on the map, deliveries for society and strategic and organizational objectives can be defined, establishing the causal relationship between the presented levels. It is observed that the lack of meaningful and feasible indicators and goals to achieve strategic objectives is a common challenge, but the strategic map fills this gap.

One of the main advantages of using the BSC in organizations is the verifiable deployment of the strategy in its various units, promoting organizational alignment. This process can be carried out from the proposed strategic map, which suggests the creation and consolidation of a “strategic awareness” through management areas, which could develop tools such as service level agreements, attesting to the importance and quality of their work, with the definition of user requirements and expectations.

To implement quality practices, process management, and improvement, it is necessary to identify and choose processes that contribute to the success of the strategy, based on the unit’s strategic objectives and vital processes that impact the organization as a whole. The BSC can be used as a reference, focusing on achieving the objectives of critical processes presented on the strategic map and dimensions suggested.

One of the most common gaps in organizational management is the absence of a strategic communication program associated with an information management program that, based on facts and information, identifies the participation of all employees aligned with the organization’s objectives. In the case of organizations committed to gender equality, the use of specific maps and BSCs can be an effective means of promoting this connection.

The use of the strategic map has a direct benefit in management, as it connects strategy to governance and operational processes, allowing the execution of the strategy with excellence. For this, it is necessary to identify the key processes for the execution of strategic initiatives and align quality programs and process improvements with the previously defined value proposition.

The study of gender equality and BSC presents significant theoretical implications for understanding and effecting strategic initiatives that consider the parameters of SDG 5. These initiatives are relevant to the three pillars of sustainable development—economic, social, and environmental. The BSC is a strategic management tool that aims to align organizational objectives and goals with key performance indicators. In this sense, studies on gender equality can provide insights into how these indicators can be defined and measured to promote gender equity in organizations and society.

To exemplify, there are several initiatives that can be adopted, such as strengthening legal frameworks that promote equality and non-discrimination based on gender, anti-discrimination policies, gender-neutral structures, investments to strengthen multi-sectoral services and critical infrastructures, economic financial assistance, and training with financial support to empower women in resource allocation. In this regard, it is important to consider the use of incentives and rewards that go beyond traditional types of financial recognition, seeking creative and appropriate solutions for each case [

90].

The use of BSC can contribute to the promotion of gender equity through the incorporation of specific indicators, such as the proportion of women in leadership positions, the average remuneration of men and women in the organization, the participation rate of women in training and development opportunities, among others. The inclusion of these indicators in the BSC can help organizations monitor and measure their performance in relation to gender equity, identify areas for improvement, and set clear goals to promote gender equality.

Furthermore, another practical implication of studies on the BSC is the possibility of adapting the tool to different organizational and social contexts. For example, a private company can use gender equity indicators that contribute to its market strategy, while a nonprofit organization can measure social impact.

However, it is important to emphasize that the successful implementation of the BSC requires a clear understanding of the strategic objectives and key performance indicators relevant to each organization. Further research can implement these practical implications through the analysis of how companies adapt the BSC to different contexts, how the tool is used to evaluate individual performance, and how the BSC contributes to organizational success in different sectors.

The Managerial Implications of a BSC Proposal for Gender Equality and Sustainable Development

The issue of gender disparity is a prevalent issue that affects sustainable development, social welfare, and economic growth. Promoting gender parity has significantly impacted the performance of for-profit businesses, nonprofit organizations, and public institutions. This study proposes a redesign of the BSC, a strategic management tool developed by Kaplan and Norton, that prioritizes gender parity to have a substantial managerial impact on private enterprises, government organizations, and NPSEs.

The proposed redesign of the BSC would integrate gender equality considerations into the strategic decision-making processes of organizations developing several managerial implications. This would require managers to recognize the value of gender parity in achieving organizational goals and objectives and create suitable metrics to track the development of gender equality. By creating and consolidating “strategic awareness” through management areas, the strategy map can help ensure that all employees are aligned with the organization’s objectives and understand their role in achieving gender equity.

Additionally, the revised BSC would boost accountability for gender equality outcomes by requiring managers to monitor and report progress toward gender parity through gender-related metrics, such as the proportion of women in leadership positions, the average remuneration of men and women in the organization, and the participation rate of women in training and development opportunities. The inclusion of these indicators in the BSC can help organizations monitor and measure their performance in relation to gender equity, identify areas for improvement, and set clear goals to promote gender equality.

Furthermore, the revised BSC can enable organizations to pinpoint areas where gender inequality is most prevalent and prioritize measures to solve these problems. By tracking gender-related data, such as the gender pay gap or the representation of women in leadership positions, managers can identify areas with the most significant gender imbalance and take appropriate remedial action. The use of incentives and rewards can also be an effective means of bolstering these actions, although it is important to consider creative and appropriate solutions for each case to ensure that incentives and rewards are meaningful and aligned with the organization’s overall objectives.

In addition to promoting gender equality, the redesigned BSC may also raise employee satisfaction and engagement levels by fostering a more diverse and inclusive workplace culture that values every employee. This can enhance employee retention, productivity, and morale.

Overall, the practical implications of this study for promoting gender equity in organizations are significant, and the redesigned BSC can contribute to achieving the fifth sustainable development goal proposed by the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Further research can analyze how companies adapt the BSC to different contexts, evaluate individual performance using the tool, and explore how it contributes to organizational success in different sectors.

7. Final Considerations

In conclusion, this research highlights the vital role that women play in driving social change and sustainable development. Although there have been various regional and global efforts to introduce gender parity programs, the lack of an effective management system has hindered progress within private enterprises, government organizations, and NPSEs. This study proposes a new method for achieving gender equality by using the BSC as a strategic management tool. By incorporating all targets and indicators outlined by SDG 5, this new BSC framework enhances accountability and responsibility while also promoting immersion in gender-specific matters across organizations and civil society. The research suggests that engagement at all levels is necessary to achieve gender equality goals and metrics for sustainable development. While this study demonstrates the efficacy of the BSC method in promoting gender equality and sustainable development, further research could explore other aspects of gender equality and assess how effectively the BSC can tackle these issues. Ultimately, the development of this new BSC structure offers a valuable contribution to the field of gender parity, business management, and sustainable development.

8. Limitations and Future Recommendations

Although this study’s goal was to examine the relevant factors to evaluate the advantages of using the BSC for gender equality as a management tool, it is critical to note that this study was limited in scope. Specifically, it does not address confounding factors such as other strategic management tools or risks involved in the process, which could have influenced the results. Therefore, future research could consider these factors to provide a more thorough understanding of how the BSC affects gender equality in management practices.

While a generic application of the BSC has been recommended, suggesting progress in supporting its viability in other contexts, it is essential to recognize that each organization has an approach of its own. The BSC’s implementation is much more intricate and complex as a result. Therefore, it is strongly advised that the continuation of this research include more in-depth qualitative studies to thoroughly comprehend the mechanisms that account for the relationships between BSC constructs and measurement with longitudinally collected data. By doing this, it will be possible to improve the BSC methodology’s application more accurately and uniquely for each organization, ultimately leading to more effective and efficient strategy execution.

To enhance this research and identify paths for future studies, the following suggestions can be considered: (i) replicating this study in a sample of companies that adopt policies aimed at gender equality or in public institutions at the state or national level could evaluate the applicability of the BSC methodology in these organizations and verify if the benefits identified in the current research are maintained in these contexts. Further examination of these topics through quantitative and qualitative research could offer additional compelling evidence of the advantages of the BSC methodology in different types of organizations; and (ii) measuring alternate management approaches and comparing them with the BSC methodology may help identify which strategies are more effective in specific organizational contexts and emphasize their benefits and drawbacks. Additionally, an in-depth examination of the data gathered may provide additional details about the components that affect the execution and efficacy of these management techniques. (iii) Analyzing the results from businesses with various types of organizational structures, including small, medium, and big organizations, can demonstrate how the BSC approach can be adjusted to meet the unique requirements of each type of organization. Further, this study’s continuation through qualitative research, long-term data collection, and in-depth examination of the relationships between the constructs might enhance understanding of the BSC methodology’s application and advantages in various organizational contexts. (iv) Lastly, further research can be conducted to include indicators within each of the proposed measures and translate them into performance indicators and dashboards.