Ensuring Sustainable Academic Development of L2 Postgraduate Students and MA Programs: Challenges and Support in Thesis Writing for L2 Chinese Postgraduate Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Challenges in Thesis Writing

2.2. Possible Support for Thesis Writing

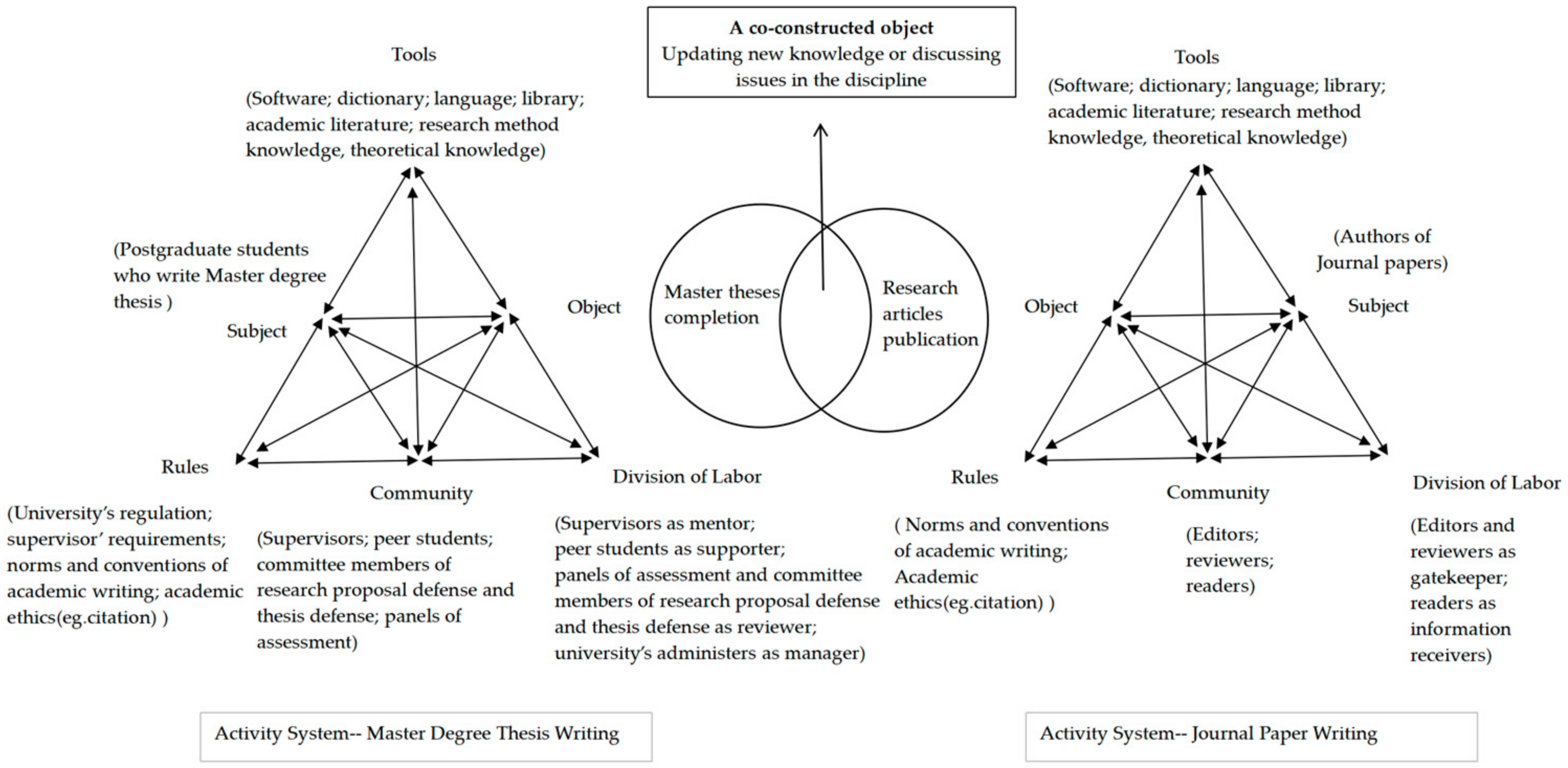

3. Theoretical Framework

- What are the major challenges that EFL postgraduate students meet in the process of writing an MA thesis?

- What kinds of support are provided for EFL postgraduate students to overcome the challenges of writing an MA thesis?

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Research Design

4.2. Research Participants and the MA Programs

4.3. Data Collection

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Research Results and Discussion

5.1. Primary Challenges and Corresponding Support

The process was rather painful. If you wanted to have a better understanding of these theories put forward by linguists, you had to spend some time reading their books.

If my supervisor had not let us do research based on her research project, we (Michele and her fellow students) would not have known what kind of research to do. We really had no idea.

Creativity was really difficult to measure. There was no authoritative or convincing questionnaire. About half of the content in my thesis proposal did not appear in my final thesis.

5.2. Secondary Challenges and Corresponding Support

5.2.1. Challenges from the High Requirements of an MA Thesis and Corresponding Support

Whether it is the academic conventions or construction of a theoretical framework or research method, accuracy of data, depth and breadth of discussion, as well as formats and the duplicate rate, the standard for postgraduate students is much higher than for undergraduates.

Maybe the creativity of our research is comparatively low, but we can go through the whole process of doing research. Then, we transform the research into a written discourse that obeys the conventions of academic writing.

My supervisor suggested that the title should contain at least three elements, such as research perspective, research subjects, and research method.

I always referred to theses written by former postgraduate students who had already graduated and who used to be in my supervisor’s research group.

When the committee members of the thesis defense pointed out the problems of other defenders, I would take notes. When I wrote my own thesis, I would pay attention to these points.

5.2.2. Challenges from Pragmatic Use of Language and Corresponding Support

If I did not know the usage or the collocation of the word, I would check in COCA to see whether the expression could be used in this way. If I found a similar expression, I would use it.

I always considered whether the selection of the word was accurate, whether the expression was negative, whether the prosody was proper, and whether the collocation was accurate.

Among all the four students in the same group, two students have studied abroad for one year, so they have a high level of language proficiency. The other one has an even higher level of language proficiency, even though she has not gone abroad.

5.2.3. Challenges from Using Research Instruments and Corresponding Support

At first, I was not familiar with Antconc. While I attended the course, I followed step-by-step what the instructor taught in class. Finally, I found it was not hard to handle.

I would always resort to my supervisor when I encountered difficulties. My supervisor always recommended to me some useful tools, websites, and platforms that he often used and told me to try. My supervisor is very smart and good at finding some useful tools, so I always asked my supervisor for help.

The faculty member who taught literature retrieval was a doctoral degree student, so he would also teach us how to write a literature review and how to operate some related tools, such as CiteSpace.

5.3. Tertiary Challenges and Corresponding Support

It is not easy to form a big map for related literature. I always negated the way I reviewed literature. You should read a lot of literature so that you can tell the whole story of the specific field.

I explored and excavated more related literature from these two articles, especially from the citations and references. I downloaded and collected all these cited and referenced articles. The process was just like a snowball rolling, from one article to plenty of articles.

I would consult previous notes taken in courses, courseware, or online resources, or imitate others’ literature reviews.

5.4. Quaternary Challenges and Corresponding Support

It was challenging for postgraduate students (master’s students), for the discussion could not be too shallow, and we had to interact with previous studies.

I spent much time writing and revising the results and the discussion and deleting much of the content. My supervisor gave me a lot of detailed instructions on the results and the discussion.

The suggestion the reviewer gave was pertinent. I agreed with his comments. In the discussion section, I repeated my opinion with different kinds of expression. I did not know how to make it deep. I feel I lacked the ability. I know I have to write a more in-depth discussion, but it is hard.

I attended one of my supervisor’s academic seminars. He said the discussion was not about talking to yourself. The result was a faceless report, so you had to interact with other literature.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Interview Protocol (translated from the Chinese Version)

- 1.

- What is the process for your master’s degree thesis writing? How do you feel about the process or experience?

- 2.

- What’s the topic of your master’s thesis?

- 3.

- Did you feel the process of master’s thesis writing was hard?

- 4.

- What are the challenges or difficulties? How did you handle those problems or difficulties?

- 5.

- How did your supervisor help you deal with the challenges you faced?

- 6.

- What other kinds of support did you get?

- 7.

- Do you think the above-mentioned support was helpful and effective?

- 8.

- What are your university’s requirements for a master’s thesis? What’s the major procedure to finish a master’s thesis, according to your university?

- 9.

- What have you learned from the process of master’s thesis writing?

- 10.

- How does this experience influence your PhD study? How might this experience impact your academic career in the future?

References

- Dong, Y.R. Non-native graduate students’ thesis/dissertation writing in science: Self-reports by students and their advisors from two U.S. institutions. Engl. Specif. Purp. 1998, 17, 369–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Johnson, M. Online mentoring of dissertations: The role of structure and support. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanave, C.P.; Hubbard, P. The writing assignments and writing problems of doctoral students: Faculty perceptions, pedagogical issues, and needed research. Engl. Specif. Purp. 1992, 11, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitchener, J.; Basturkmen, H. Perceptions of the difficulties of postgraduate L2 thesis students writing the discussion section. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2006, 5, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitchener, J.; Basturkmen, H.; East, M. The focus of supervisor written feedback to thesis/dissertation students. Int. J. Engl. Stud. 2010, 10, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hyland, K. Elements of doctoral apprenticeship: Community feedback and the acquisition of writing expertise. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2021, 53, 100835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannino, A.; Engeström, Y.; Lemos, M. Formative interventions for expansive learning and transformative agency. J. Learn. Sci. 2016, 25, 599–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, P. Science research students’ composing processes. Engl. Specif. Purp. 1991, 10, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Carter, S.; Zhang, L.J. EL1 and EL2 doctoral students’ experience in writing the discussion section: A needs analysis. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2019, 40, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H. Supervisors’ views of the generic difficulties in thesis writing of Chinese EFL research students. Asian J. Appl. Linguist. 2018, 5, 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Itua, I.; Coffey, M.; Merryweather, D.; Norton, L.; Foxcroft, A. Exploring barriers and solutions to academic writing: Perspectives from students, higher education and further education tutors. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2014, 38, 305–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paltridge, B.; Woodrow, L. Thesis and dissertation writing: Moving beyond the text. In Academic Writing in a Second or Foreign Language: Issues and Challenges Facing ESL/EFL Academic Writers in Higher Education Contexts; Tang, R., Ed.; Continuum: London, UK, 2012; pp. 88–104. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, S.; Kumar, V. ‘Ignoring me is part of learning’: Supervisory feedback on doctoral writing. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2017, 54, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basturkmen, H.; East, M.; Bitchener, J. Supervisors’ on-script feedback comments on drafts of dissertations: Socialising students into the academic discourse community. Teach. High. Educ. 2014, 19, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L. Investigating L2 writing through tutor-tutee interactions and revisions: A case study of a multilingual writer in EAP tutorials. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2020, 48, 100709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane Bastola, M. Engagement and challenges in supervisory feedback: Supervisors’ and students’ perceptions. RELC J. 2022, 53, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane Bastola, M.; Hu, G.W. “Chasing my supervisor all day long like a hungry child seeking her mother!”: Students’ perceptions of supervisory feedback. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2021, 70, 101055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odena, O.; Burgess, H. How doctoral students and graduates describe facilitating experiences and strategies for their thesis writing learning process: A qualitative approach. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 572–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargar, R.R.; Mayo-Chamberlain, J. Advisor and advisee issues in doctoral education. J. High. Educ. 1983, 54, 407–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, S.K. “What’s too much and what’s too little?”: The process of becoming an independent researcher in doctoral education. J. High. Educ. 2008, 79, 326–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, C.; Meier, N.; Ingerslev, K. Borrowing brainpower—Sharing insecurities. Lessons learned from a doctoral peer writing group. Stud. High. Educ. 2016, 41, 1092–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S. Learning from giving peer feedback on postgraduate theses: Voices from Master’s students in the Macau EFL context. Assess. Writ. 2019, 40, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poverjuc, O.; Brooks, V.; Wray, D. Using peer feedback in a Master’s programme: A multiple case study. Teach. High. Educ. 2012, 17, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.P.F. Academic writing support through individual consultations: EAL doctoral student experiences and evaluation. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2019, 43, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusslin, S.; Widlund, A. Academic writing workshop-ing to support students writing bachelor’s and master’s theses: A more-than-human approach. Teach. High. Educ. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y. Learning by Expanding: An Activity-Theoretical Approach to Developmental Research, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, D.R. Rethinking genre in school and society: An Activity Theory analysis. Writ. Commun. 1997, 14, 504–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y. Developmental studies of work as a test bench of activity theory: The case of primary care medical practice. In Understanding Practice: Perspectives on Activity and Context; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993; pp. 64–103. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, L. The activity of student research: Using Activity Theory to conceptualise student research for Master’s programmes. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 46, 1055–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y. Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. J. Educ. Work 2001, 14, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.K.A.; Carbone, A.; Ye, J.; Vu, T.T.P. How academics manage individual differences to team teach in higher education: A sociocultural activity theory perspective. High. Educ. 2022, 84, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Meschitti, V. Can peer learning support doctoral education? Evidence from an ethnography of a research team. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 1209–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka, M. L2 student–U.S. professor interactions through disciplinary writing assignments: An Activity Theory perspective. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2014, 25, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J. Publishing during doctoral candidature from an Activity Theory perspective: The case of four Chinese nursing doctoral students. TESOL Q 2019, 53, 655–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Lee, I. Exploring Chinese students’ strategy use in a cooperative peer feedback writing group. System 2016, 58, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassaji, H. Good qualitative research. Lang. Teach. Res. 2020, 24, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.; Joffe, H. Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 1609406919899220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K.M. International EFL/ESL Master students’ adaptation strategies for academic writing practices at tertiary level. J. Int. Stud. 2017, 7, 620–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravari, K.Z.; Ul Islam, Q.; Khozaei, F.; Zarvijani, S.B.C. Factors that hinder the thesis writing process of non-native MA students in ELT: Supervisors’ perspectives. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2022. online ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, N.; Petrić, B. Helping international Master’s students navigate dissertation supervision: Research-informed discussion and awareness-raising activities. J. Int. Stud. 2019, 9, 150–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komba, S.C. Challenges of writing theses and dissertations among postgraduate students in Tanzanian higher learning institutions. Int. J. Res. Stud. Educ. 2016, 5, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manathunga, C. Early warning signs in postgraduate research education: A different approach to ensuring timely completions. Teach. High. Educ. 2005, 10, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Yang, L. Exploring Contradictions in an EFL teacher professional learning community. J. Teach. Educ. 2018, 70, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Zhu, W. A Chinese EFL student’s strategies in graduation thesis writing: An Activity Theory perspective. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2023, 61, 101202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Contradiction Level | Engeström’s Definition |

|---|---|

| Primary contradiction | Within each constituent component of the central activity |

| Secondary contradiction | Between the constituents of the central activity |

| Tertiary contradiction | Between the object/motive of the dominant form of the central activity and the object/motive of a culturally more advanced form of the central activity |

| Quaternary contradiction | Between the central activity and its neighboring activities |

| No. | Pseudonym | Age | Gender | Year of Graduation | Thesis Topic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Candy | 38 | Female | 2021 | Cognitive Linguistics |

| 2 | Michele | 28 | Female | 2021 | Term Translation |

| 3 | Bob | 25 | Male | 2022 | Academic Writing |

| 4 | Emily | 26 | Female | 2022 | Multimodal Writing |

| 5 | Jessie | 29 | Female | 2020 | News Discourse Analysis |

| Theme | Codes |

|---|---|

| Primary challenges | Selecting a research topic |

| Corresponding support | Suggestions from supervisors Feedback from the thesis proposal defense committee Inspiration from research conferences |

| Theme | Codes |

|---|---|

| Secondary challenges | Meeting the high requirements of a master’s thesis |

| Linguistic barriers in academic writing | |

| Using new research tools | |

| Corresponding support | Supervisors’ instruction; theses and research articles as references; peer feedback; thesis defense; academic writing courses |

| Electronic dictionary/corpus; supervisors’ feedback; journal articles as references; peer proofreading | |

| Research methodology courses; supervisors’ instruction; workshops; library lectures |

| Theme | Codes |

|---|---|

| Tertiary challenges | Writing the literature review logically, critically, and comprehensively |

| Corresponding support | Supervisors’ instruction Group meetings hosted by the supervisor Literature analytical tools |

| Theme | Codes |

|---|---|

| Quaternary challenges | Interacting with related studies in the discussion |

| Corresponding support | Feedback from supervisors Panels of assessment Academic seminars Published empirical research articles as references |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Man, J.; Zhan, J. Ensuring Sustainable Academic Development of L2 Postgraduate Students and MA Programs: Challenges and Support in Thesis Writing for L2 Chinese Postgraduate Students. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14435. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914435

Man J, Zhan J. Ensuring Sustainable Academic Development of L2 Postgraduate Students and MA Programs: Challenges and Support in Thesis Writing for L2 Chinese Postgraduate Students. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14435. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914435

Chicago/Turabian StyleMan, Jing, and Ju Zhan. 2023. "Ensuring Sustainable Academic Development of L2 Postgraduate Students and MA Programs: Challenges and Support in Thesis Writing for L2 Chinese Postgraduate Students" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14435. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914435

APA StyleMan, J., & Zhan, J. (2023). Ensuring Sustainable Academic Development of L2 Postgraduate Students and MA Programs: Challenges and Support in Thesis Writing for L2 Chinese Postgraduate Students. Sustainability, 15(19), 14435. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914435