Appraisal of Provision Structures of Nursing Homes for Old Persons—Illustrated by Cross-Sectional Data for East Tyrol

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Epistemological Interest and Purpose of the Paper

2.1. People at Old Age in Austria

2.2. Guiding Principles of Spatial Planning in German-Speaking Countries

2.3. Austrian Legal Framework for Demand and Location Planning of Long-Term Care Infrastructures

3. Conceptual Framework and Related Research

- The explanation of the evolution of spatial supply structures and the allocation of facilities (see, for instance, ref. [41] for Chile);

- The assessments of (current) spatial patterns of provision at different spatial reference levels, considering the socio-economic profile and needs of the population—for the city context (city, neighbourhoods), see, for instance, ref. [42] for Tokyo; and for national and regional contexts, ref. [41] for Chile and [43] for the Czech Republic. An overview of the potential of GIS-based approaches recently was provided by Higgs et al. [44], illustrated by the example of Wales;

- Normative need (p. 2) is defined by experts, administrators or scientists, e.g., the number beds in a nursing home per persons of a defined age group;

- Felt need (p. 3) is defined as the needs identified by individuals themselves; felt need can be regarded as a prerequisite for identifying oneself as a potential user of a particular commodity or infrastructure;

- Expressed need (p. 3) or “felt need turned into action” becomes visible in a concrete demand, which can either already be met or not (yet) met. Nonetheless, waiting lists are “generally accepted as a poor definition of ‘real need’”;

- Comparative need (p. 3f) is used for a comparative depiction of the satisfaction of felt needs of “people with similar characteristics” (p. 3). An example for this is the share of persons who have already been admitted to a nursing home compared to persons of the same care level and the same (urgent) need for stationary long-term care, but who have not (yet) been admitted. Another example could be the comparison of persons whose wish for accommodation close to their (former) place of residence is fulfilled and those whose wish in this regard could not be fulfilled.

4. Materials and Methods

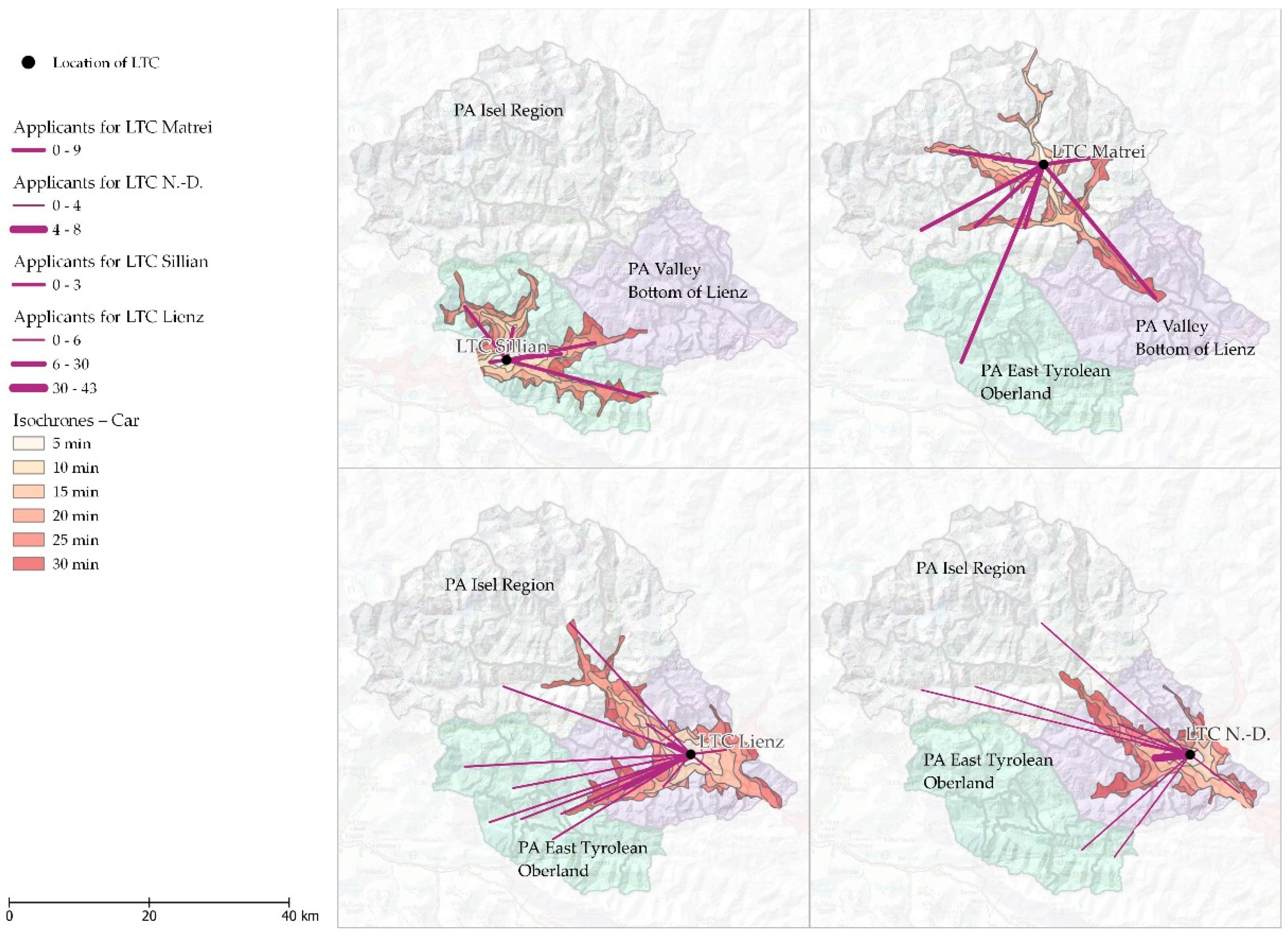

- The spatial analysis focused on the regional level, considering any intra-regional disparities. The aspect of (pedestrian) accessibility of LTC within the location municipalities was, therefore, not the subject of the analysis;

- The spatial range of LTC served to operationalise the catchments and the catchments were defined on the basis of the (former) municipality of main residence of the LTC residents or LTC applicants;

- Waiting lists were used to operationalise the “expressed needs” according to Bradshaw. The capacities of LTC and the (unsatisfied) need was collectively considered as an expression of an insufficient fit of supply and demand, on the one hand, and the identification of over- and undersupply, on the other;

- Isochrones by car served to operationalize the travel efforts for (future) visitors who still lived in the same (former) municipality as the residents or applicants—this primarily applied to spouses and life partners;

- The focus was exclusively on stationary long-term care. Therefore, transient, day care and short-term care were not addressed.

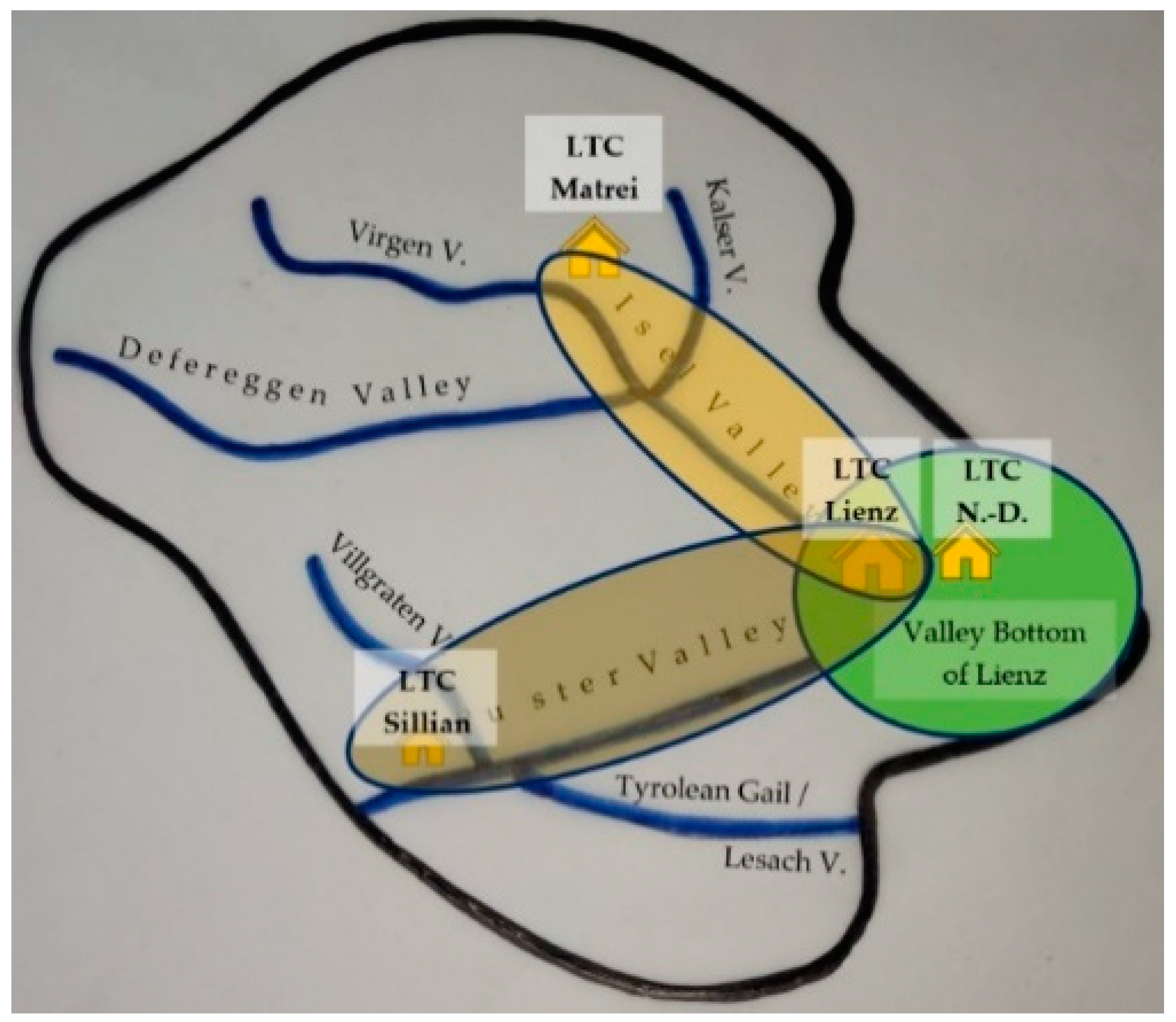

4.1. Rationale for the Choice of a Particular Case Study Region

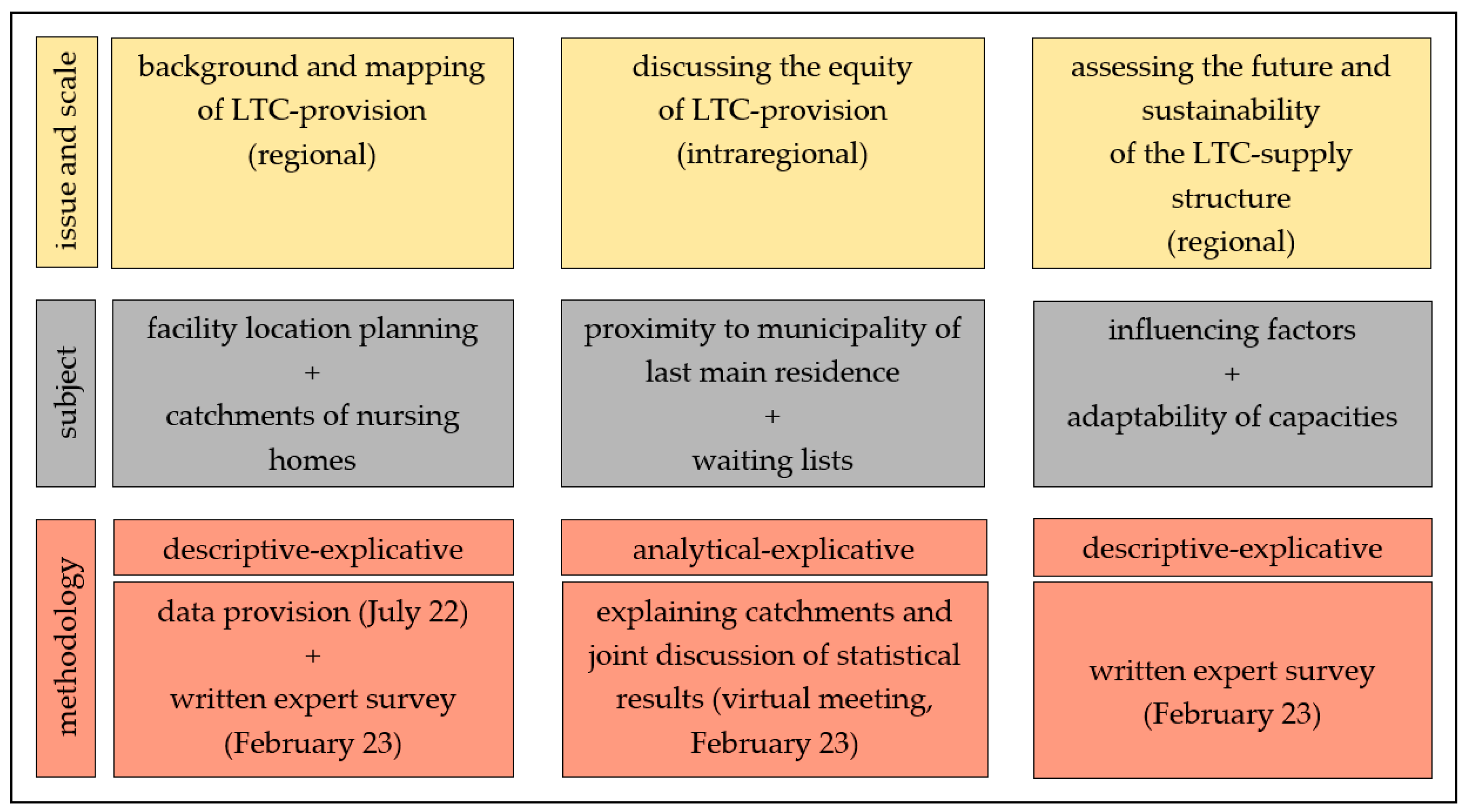

4.2. Science–Practice Collaboration, Data Processing and Data Analysis

- Expert 1: the operative manager of the East Tyrolean LTC with more than 20 years of experience as a representative of the LTC provider.

- Expert 2: the (former) expert (up to his retirement in 2022) in charge of social planning in the Department of Social Affairs of the Office of the Tyrolean Provincial Government; he is co-author of the Structural Plan for Care 2012–2022 (in German, Strukturplan Pflege 2012–2022) [60] and the corresponding evaluation report [61].

4.2.1. Real-World Data

- The number of residents of the four LTC and a list of urgent applications for admission to a home (waiting list) (=applicants). The following information was available for each LTC: number of residents, cost share of residents, in day care or stationary care, care level; municipality of (previous) main residence (“origin”) of residents and applicants by PAs and by valleys.

- Information on the demographic profile of the residents and applicants overall: sex, age (5-year classes), marital status and religion.

- According to the home provider, the mid-year data are considered to be representative of the annual average. This applies both to the residents and the applicants.

4.2.2. Statistical Analysis

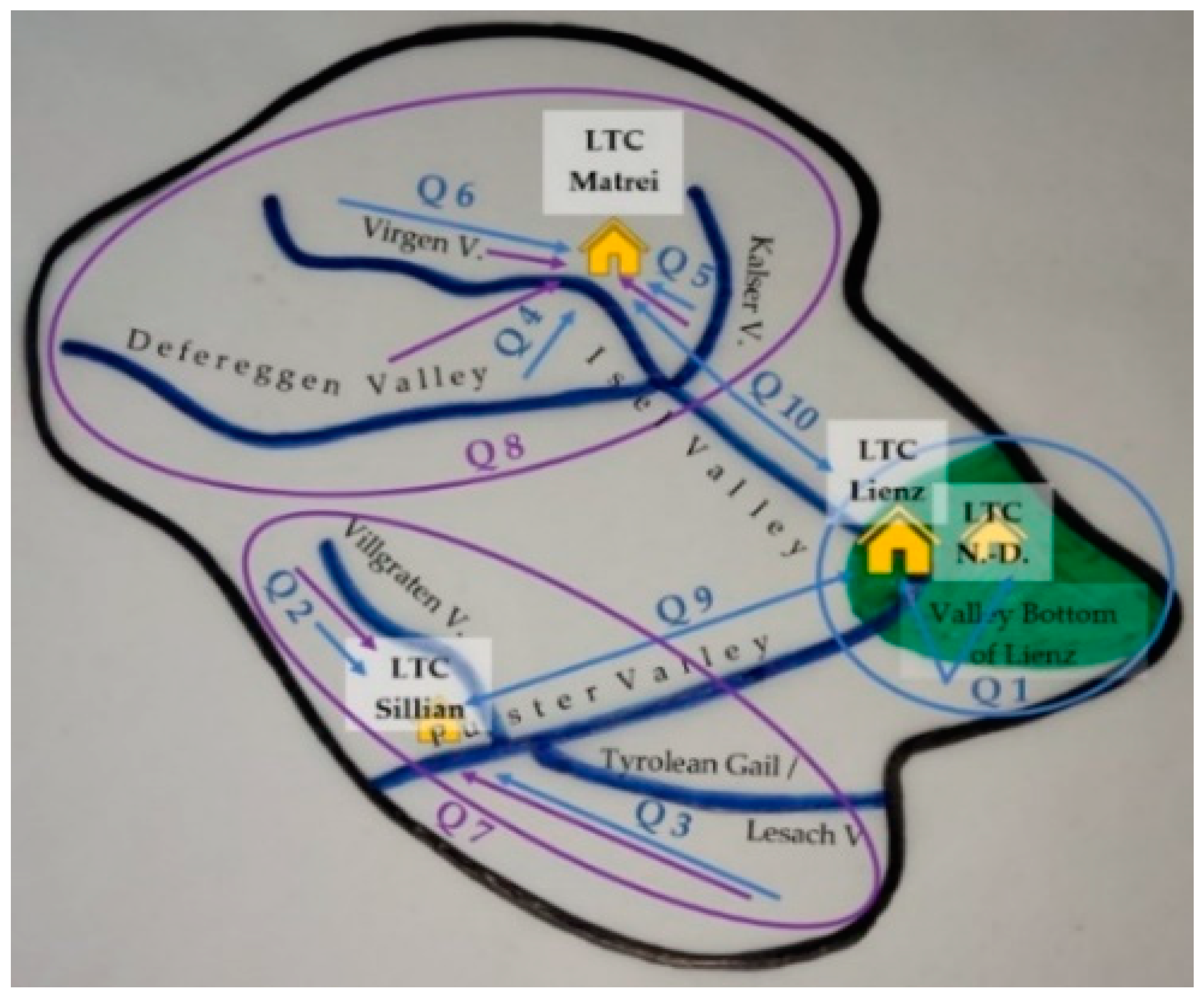

- Are there significant differences among the four nursing homes with respect to the percentage of residents or applicants who previously lived a municipality belonging to the planning unit area to which the respective LTC is assigned?

- Are there significant differences among the four nursing homes regarding the proportion of residents or applicants who previously lived in or outside the respective LTC location municipality?

4.2.3. Fundamental Data Themes for Geovisualisation and Explanation of Procedure

4.2.4. Transdisciplinary Discussion of Findings

5. Results

5.1. Overview of LTC Supply Structure

5.2. Levels of Provision, Admission Criteria and the Profile of the LTC Residents and Applicants

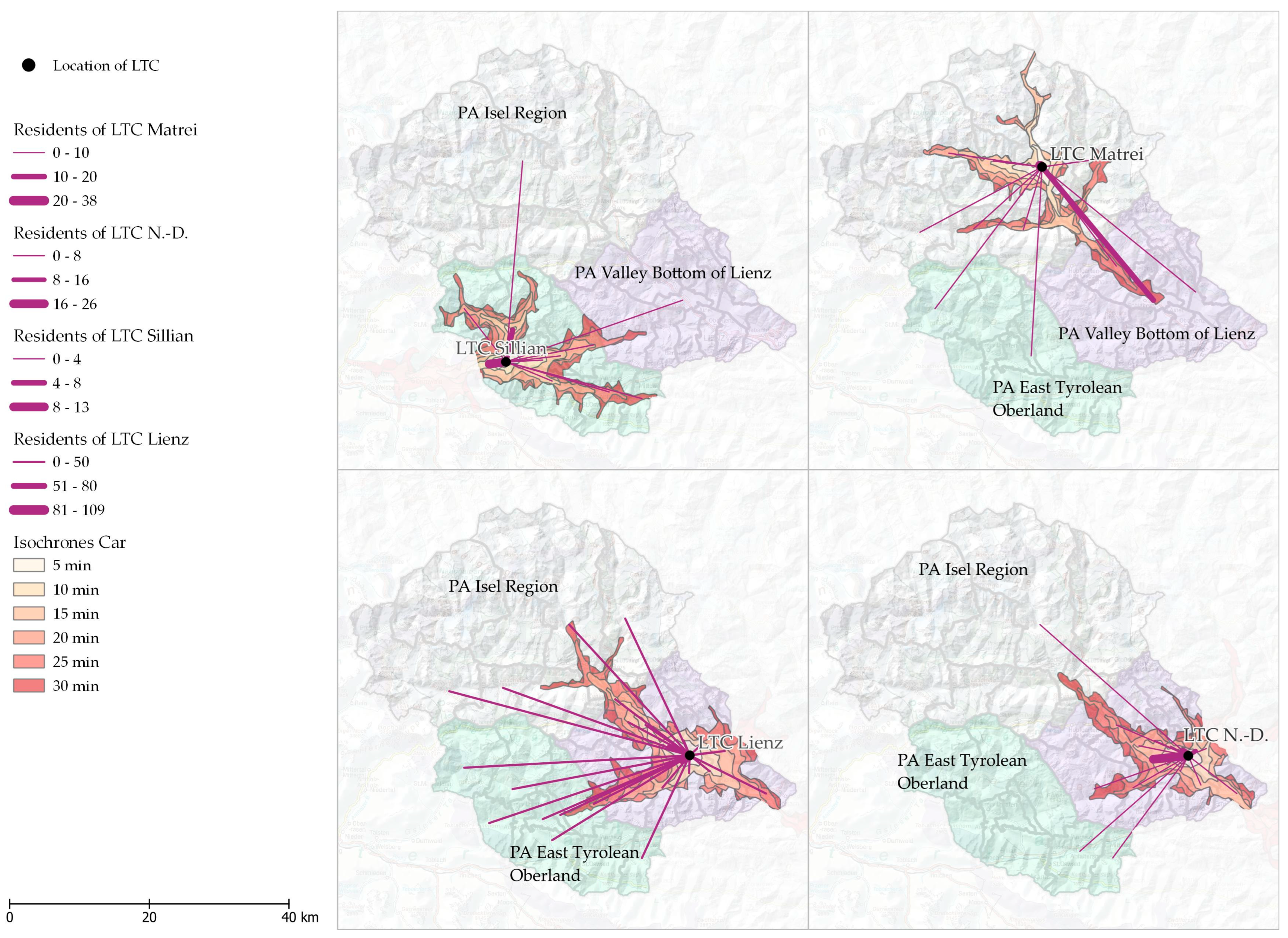

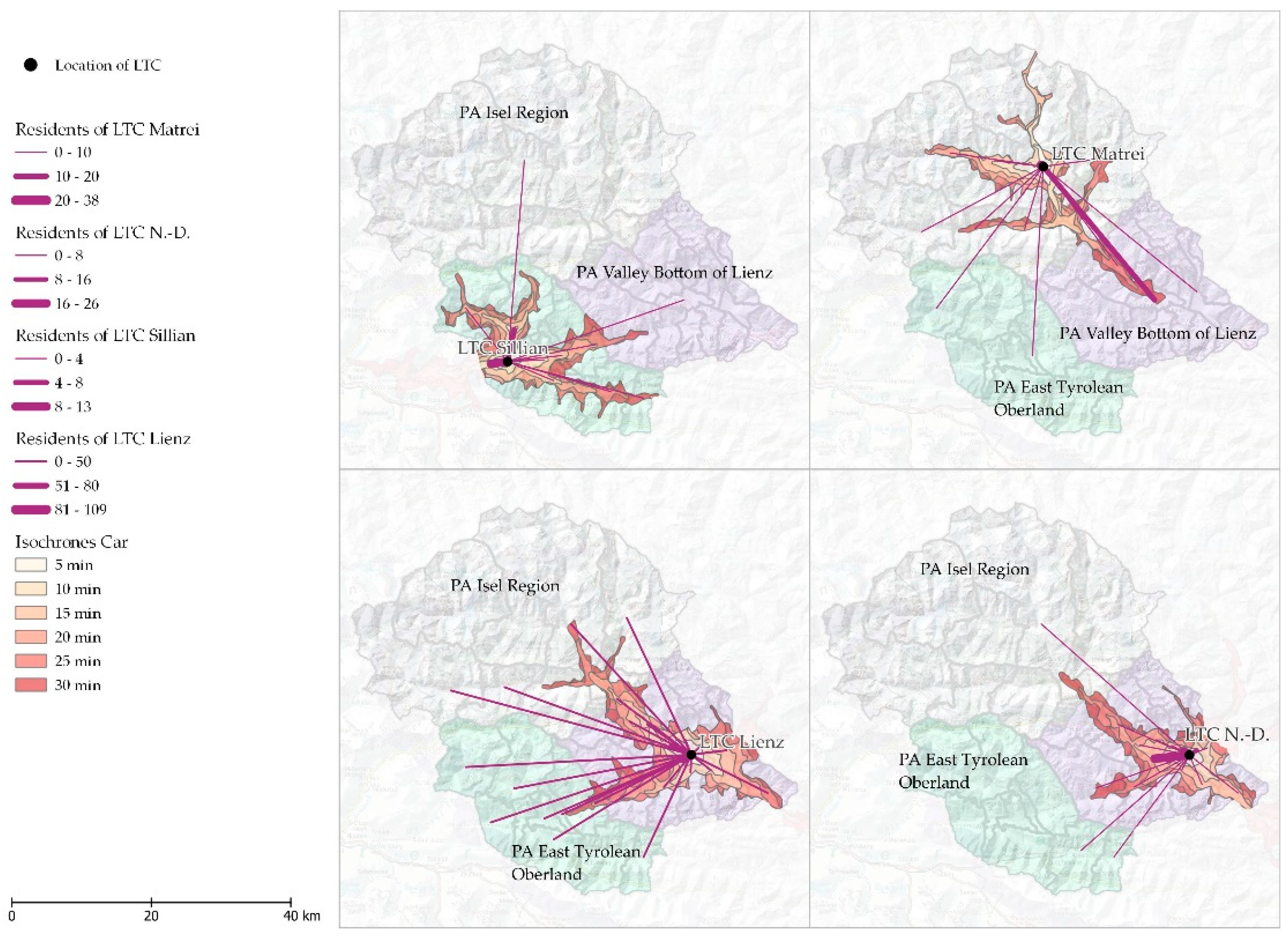

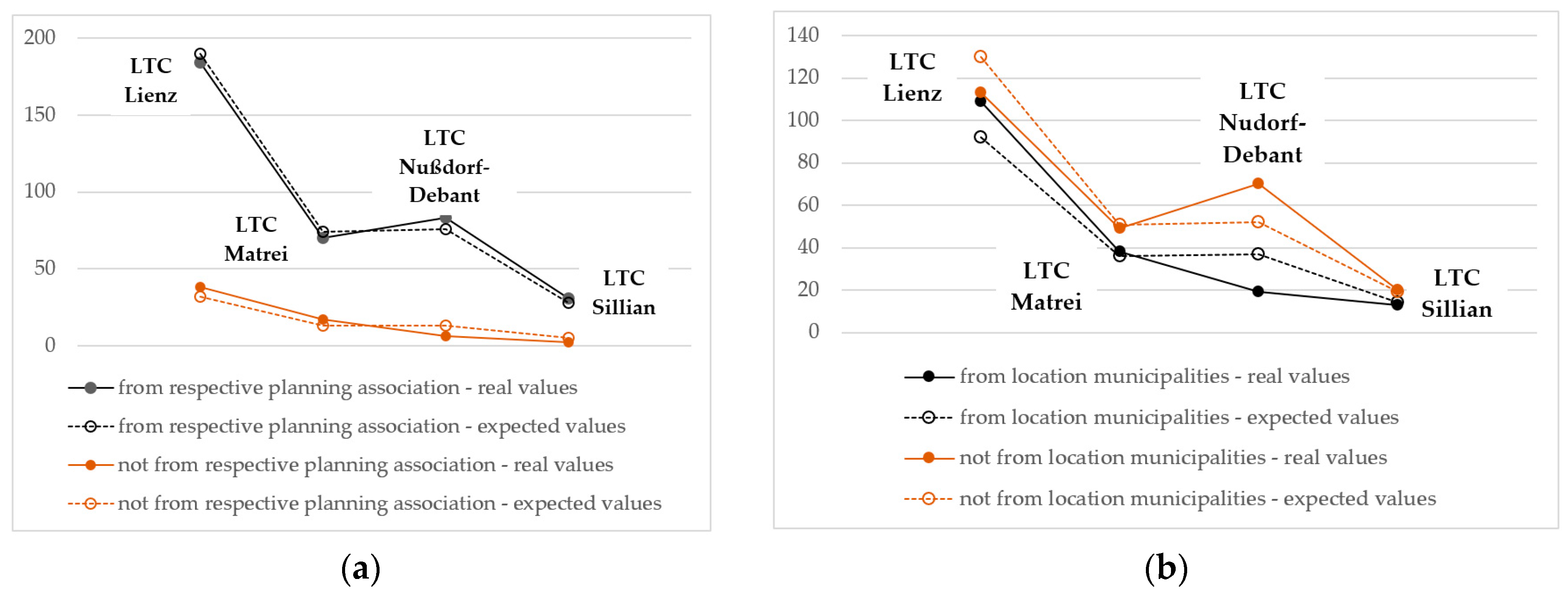

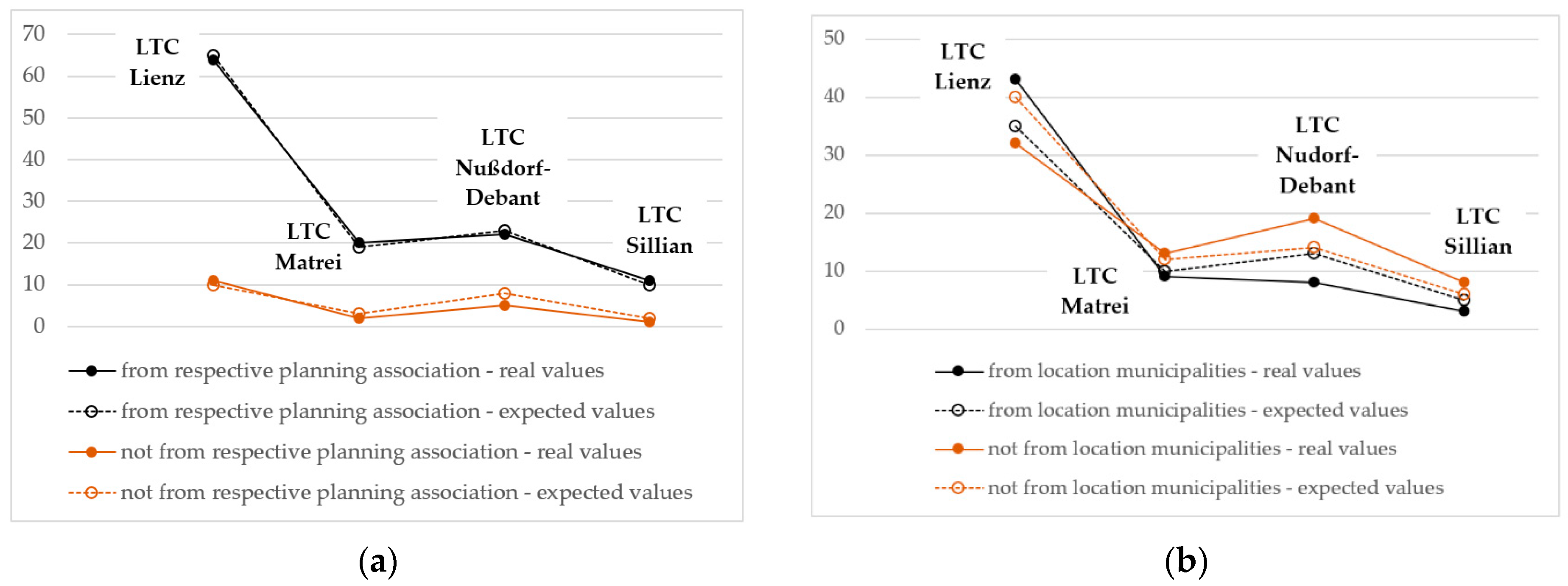

5.3. Catchments Related to LTC Residents

- The resident and the relatives decided to take the first available opportunity to satisfy the (urgent) felt need for LTC, settled in and, therefore, excluded a further move—possibly also due to a changing family environment;

- The residents’ children moved to a municipality that is part of another planning association and that is why their parent(s) in need of care decided to reside there, to be closer to them;

- The resident was an “unloved family member” and so the opportunity was taken to place her/him far away.

- Significantly more persons from the Bottom Valley of Lienz resided in LTC Lienz and LTC Nußdorf-Debant compared to the other two facilities (p < 0.0001).

- Persons from Virgen Valley resided significantly more often in LTC Matrei compared to the other three LTC (p = 0.0039).

- LTC residents of Defereggen Valley, Kalser Valley and Virgen Valley had decided significantly more often on LTC Matrei compared to the other three LTC (p = 0.0026).

- Significantly more persons from the Puster Valley resided in LTC Sillian and LTC Lienz compared to the other two facilities (p < 0.0001).

- LTC residents who came from the Isel Valley had chosen significantly more often to move to LTC Matrei or LTC Lienz compared to the other two facilities (p < 0.0001).

5.4. Catchments Related to LTC Applicants

- Significantly more persons from the Valley Bottom of Lienz applied for admission to LTC Lienz and LTC Nußdorf-Debant compared to the other two nursing homes (p < 0.0001).

- Significantly more persons from the Puster Valley applied for admission to LTC Sillian and LTC Lienz compared to the other two LTC facilities (p = 0.0001).

- Significantly more persons from the Isel Valley applied for admission to LTC Matrei and LTC Lienz compared to LTC Sillian and LTC Nußdorf-Debant (p = 0.0126).

5.5. Travel Effort for (Future) Visitors

5.6. Experts’ Outlook on the Near Future of LTC Provision

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Strengths and Limitations of this Study

6.2. The Case Study Region as a Container with Shortcomings of Provision

- LTC location planning (so far) has been oriented towards the concept of central locations;

- The case study region has the character of a container with regard to the origins of the residents and applicants, i.e., the catchment areas are limited to the political district of Lienz;

- Normatively determined catchment areas (PAs) broadly match the actual catchments;

- The disparities in terms of intra-regional supply levels (most probably due to demographic ageing) have increased compared to the reference year 2010;

- The travel efforts of (future) visitors are heterogeneous and differ between one LTC and another;

- The current demand is not met by the existing utilisable capacities.

- The beds of the four nursing homes will continuously be fully occupied—at present 430 of about 450 places can be occupied due to the staff shortage—and that the capacities cannot be adjusted to the increasing demand in the short term—at the time of the study, the waiting time for admission was about one year;

- Waiting lists are taken as the only source of input for calculating the current need for additional beds.Then,

- If each applicant actually has an urgent need and if each person is only listed once on the waiting list, and it is postulated that all theoretically available beds in the existing nursing homes can actually be occupied, this will result in a theoretical need for 116 additional beds “for now”. Only considering their need, this will mean that at least one additional nursing home will have to be built in the case study region; with regard to the PAs and only considering applicants living in the PA-associated municipalities, this implies a current theoretical need for 15 additional beds in PA East Tyrolean Oberland, 75 additional beds in PA Valley Bottom of Lienz and 25 additional beds in PA Isel Region.

- If every second applicant is put on more than one waiting list, i.e., 68 persons urgently seek a place in a home, this will result in a theoretical need for 48 additional beds “for now”. Only considering their need, this implies that an additional nursing home of the size of LTC Sillian is needed; with regard to the PAs and only considering the applicants residing in the respective PA, as well as postulated that assumption 2 applies equally to all PAs, this implies a current theoretical need for about 3 additional beds in PA East Tyrolean Oberland, about 31 additional beds in PA Valley Bottom of Lienz and about 12 additional beds in PA Isel Region.

6.3. Implications for Further Research

6.4. Lessons Learned

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Residents from … | LTC Lienz | LTC Matrei | LTC Nußdorf- Debant | LTC Sillian |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| respective planning unit area | 184 | 70 | 83 | 31 |

| LTC’s location municipality | 109 | 38 | 19 | 13 |

| neighbouring municipalities | 57 | 27 | 47 | 11 |

| outside East Tyrol | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| total | 222 | 87 | 89 | 33 |

| Name of Facility | Residents from Respective Planning Association N (%) | Residents from LTC’s Location Municipality N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| LTC Lienz | 184 (82.9) | 38 (17.1) | 109 (49.1) | 113 (50.9) |

| LTC Matrei | 70 (80.5) | 17 (19.5) | 38 (43.7) | 49 (56.3) |

| LTC Nußdorf-Debant | 83 (93.3) | 6 (6.7) | 19 (21.3) | 70 (78.7) |

| LTC Sillian | 31 (93.9) | 2 (6.1) | 13 (39.4) | 20 (60.6) |

| total | 368 (85.4) | 63 (14.6) | 179 (41.5) | 252 (58.5) |

| Chi-Square | 0.0272 | 0.0001 | ||

| Fisher’s exact test | 0.0223 | <0.0001 | ||

| Persons from … | Residing in East Tyrolean LTC(s) | Residing in Next-Neighboured East Tyrolean LTC(s) | Chi-Square p | Confidence Interval of Binomial Distribution | Assessment of Binomial Distribution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||

| Valley Bottom of Lienz | 257 | 243 | 14 | <0.0001 | 0.0301–0.0898 | significant |

| Villgraten Valley | 12 | 8 | 4 | 0.2482 | 0.0992–0.6511 | |

| Tyrolean Gail/Lesach Valley | 10 | 3 | 7 | 0.2059 | 0.0667–0.6525 | |

| Defereggen Valley | 22 | 15 | 7 | 0.0881 | 0.1386–0.5487 | |

| Kalser Valley | 10 | 6 | 4 | 0.5271 | 0.3491–0.9681 | |

| Virgen Valley | 12 | 11 | 1 | 0.0039 | 0.0021–0.3848 | significant |

| Villgraten Valley and Tyrolean Gail/Lesach Valley | 22 | 11 | 11 | 1.0000 | 0.2822–0.7178 | |

| Defereggen Valley, Kalser Valley and Virgen Valley | 44 | 32 | 12 | 0.0026 | 0.1496–0.4279 | significant |

| Puster Valley | 49 | 44 | 5 | <0.0001 | 0.0340–0.2223 | significant |

| Isel Valley | 56 | 53 | 3 | <0.0001 | 0.0112–0.1487 | significant |

| Applicants from … | LTC Lienz | LTC Matrei | LTC Nußdorf- Debant | LTC Sillian |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| respective planning unit area | 64 | 20 | 22 | 11 |

| LTC’s location municipality | 43 | 9 | 8 | 3 |

| neighbouring municipalities | 18 | 10 | 11 | 5 |

| outside East Tyrol | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| total | 75 | 22 | 27 | 12 |

| Name of Facility | Applicants from Respective Planning Association N (%) | Applicants from LTC’s Location Municipality N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| LTC Lienz | 64 (85.3) | 11 (14.7) | 43 (57.3) | 32 (42.7) |

| LTC Matrei | 20 (90.9) | 2 (9.1) | 9 (40.9) | 13 (59.1) |

| LTC Nußdorf-Debant | 22 (81.5) | 5 (18.5) | 8 (29.6) | 19 (70.4) |

| LTC Sillian | 11 (91.7) | 1 (8.3) | 3 (25.0) | 9 (75.0) |

| total | 117 (86.0) | 19 (14.0) | 63 (46.3) | 73 (53.7) |

| Chi-Square | 0.7415 | 0.0275 | ||

| Fisher’s exact test | 0.8070 | 0.0278 | ||

| Persons Living in … | Applying for Place(s) in East Tyrolean LTC(s) | Applying for Place(s) in Next-Neighboured East Tyrolean LTC(s) | Chi-Square p | Confidence Interval of Binomial Distribution | Assessment of Binomial Distribution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||

| Valley Bottom of Lienz | 78 | 77 | 1 | <0.0001 | 0.0001–0.0219 | significant |

| Villgraten Valley | 6 | 2 | 4 | 0.4142 | 0.0433–0.7772 | |

| Tyrolean Gail/Lesach Valley | 5 | 1 | 4 | 0.1797 | 0.0051–0.7164 | |

| Defereggen Valley | 8 | 5 | 3 | 0.4795 | 0.0852–0.7551 | |

| Kalser Valley | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0.0833 | 0.0000–0.7076 | |

| Virgen Valley | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0.0883 | 0.0000–0.7076 | |

| Villgraten Valley and Tyrolean Gail/Lesach Valley | 11 | 5 | 6 | 0.7630 | 0.1675–0.7662 | |

| Defereggen Valley, Kalser Valley and Virgen Valley | 14 | 11 | 3 | 0.0325 | 0.0466–0.5080 | |

| Puster Valley | 19 | 18 | 1 | 0.0001 | 0.0013–0.2603 | significant |

| Isel Valley | 13 | 11 | 2 | 0.0126 | 0.0192–0.4545 | significant |

Appendix B

References

- United Nations. 60+ Counts. The Growing Need for Long-Term Care. Assumptions and Realities. Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/ageing/documents/un-ageing_briefing-paper_long-term-care.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Tessier, L.; Wulf, N.; Momose, Y. Long-Term Care in the Context of Population Ageing: Rights-Based Approach to Universal Coverage; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 9789220379769. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.M.; Rosenberg, M.; Flores, G.; Parsell, N.; Akter, S.; Alam, M.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Edejer, T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of unmet needs for healthcare and long-term care among older people. Health Econ. Rev. 2022, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Hagger, C. The experiences of older adults from moving into residential long term care. A systematic review of qualitative studies. JBI Libr. Syst. Rev. 2011, 9, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Gemes, G.; Rich-Ruiz, M.; Serrano-Del-Rosal, R. Reasons for the Place of Care of the Elders: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2020, 8, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiefler, S.; Seibert, K.; Domhoff, D.; Görres, S.; Wolf-Ostermann, K.; Peschke, D. Einflussfaktoren für einen Heimeintritt bei bestehender Pflegebedürftigkeit—Eine systematische Übersichtsarbeit. Z. Evid. Fortbild. Qual. Gesundhwes. 2020, 153–154, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.A.; Bibbo, J. Relocation decisions and constructing the meaning of home: A phenomenological study of the transition into a nursing home. J. Aging Stud. 2014, 30, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, H.; Stroka-Wetsch, M.A. Determinants of nursing home choice: Does reported quality matter? Health Econ. 2020, 29, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, K.; Borell, L.; Rosenberg, L. Qualities of the environment that support a sense of home and belonging in nursing homes for older people. Ageing Soc. 2022, 42, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, A. Constitution of the World Health Organization. In WHO Chronicle; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. 1986. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/349652 (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Spatial Planning. Key Instrument for Development and Effective Governance with Special Reference to Countries in Transition; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Arbeit, Soziales und Konsumentenschutz. Altern und Zukunft. Bundesplan für Seniorinnen und Senioren; Bundesministerium für Arbeit, Soziales und Konsumentenschutz; Altern und Zukunft: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Statistik Austria. Metadaten für Bevölkerung zu Jahresbeginn ab 2002 (Einheitlicher Gebietsstand 2022). Available online: https://statcube.at/statistik.at/ext/statcube/jsf/tableview/tableview.xhtml (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Statistik Austria. Homepage. Gliederung Nach Städtischen und Ländlichen Gemeinden. Tabelle “Urban-Rural-Typologie Statistik Austria—Paket Bevölkerungsstand 2021”. Available online: http://www.statistik.at/web_de/klassifikationen/regionale_gliederungen/stadt_land/index.html (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Statistik Austria. Homepage. Bevölkerungsprognosen. Available online: http://www.statistik.at/web_de/statistiken/menschen_und_gesellschaft/bevoelkerung/demographische_prognosen/bevoelkerungsprognosen/index.html (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Österreichische Raumordnungskonferenz (ÖROK). 16. Raumordnungsbericht. Analysen und Berichte zur Räumlichen Entwicklung Österreichs 2018–2020; Schriftenreihe Band 209; ÖROK: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Soziales, Gesundheit, Pflege und Konsumentenschutz. Homepage. Demenz. Available online: https://www.sozialministerium.at/themen/pflege/demenz.html (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Bundesministerium für Soziales, Gesundheit, Pflege und Konsumentenschutz (BSGPK). Österreichischer Pflegevorsorgebericht 2021. Wien. 2022. Available online: https://broschuerenservice.sozialministerium.at/Home/Download?publicationId=42&attachmentName=%C3%96sterreichischer_Pflegevorsorgebericht_2021_pdfUA.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Statistik Austria. Pflegegeld. Available online: https://www.statistik.at/statistiken/bevoelkerung-und-soziales/sozialleistungen/bundespflegegeld (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Statistik Austria. Personen in Anstaltshaushalten nach Geschlecht 2020 (Tabelle). Available online: https://www.statistik.at/statistiken/bevoelkerung-und-soziales/bevoelkerung/familien-haushalte-lebensformen/anstaltshaushalte (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Republik Österreich. Die Neue Volkspartei. Die Grünen—Die Grüne Alternative. Aus Verantwortung für Österreich. Regierungsprogramm 2020–2024; Wien. 2020. Available online: https://www.dieneuevolkspartei.at/download/regierungsprogramm_2020.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Stöglehner, G.; Manhart, V. Leitbilder in der Planung. In Grundlagen der Raumplanung 1. Theorien, Methoden, Instrumente; Stöglehner, G., Ed.; Facultas Universitätsverlag: Vienna, Austria, 2019; pp. 121–148. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, T. Räumliche Disparitäten und Gleichwertige Lebensverhältnisse. In Grundlagen der Raumplanung 2. Strategien, Schwerpunkte, Konzepte, 1. Auflage; Stöglehner, G., Ed.; Facultas: Vienna, Austria, 2020; pp. 303–324. ISBN 978-3708917559. [Google Scholar]

- Österreichische Raumordnungskonferenz (ÖROK). Die Regionale Handlungsebene Stärken: Status, Impulse & Perspektiven; ÖROK-Schriftenreihe Nr. 208; ÖROK: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesamt für Eich- und Vermessungswesen. Regionalinformation. Available online: https://www.bev.gv.at/services/produkte/kataster-und-verzeichnisse/regionalinformation.html (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Österreichische Raumordnungskonferenz (ÖROK). Aufrechterhaltung der Funktionsfähigkeit ländlicher Räume—Dienstleistungen der Daseinsvorsorge und Regional Governance; ÖROK-Schriftenreihe Band 171; ÖROK: Vienna, Austria, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Christaller, W. Die Zentralen Orte in Süddeutschland. Eine Ökonomisch-Geographische Untersuchung Über die Gesetzmäßigkeit der Verbreitung und Entwicklung der Siedlungen mit Städtischen Funktionen; Fischer: Jena, Germany, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Van Meeteren, M.; Poorthuis, A. Christaller and “big data”: Recalibrating central place theory via the geoweb. Urban Geogr. 2018, 39, 122–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, G.F.; Partridge, M.D.; Carruthers, J.I. Central place theory and its reemergence in regional science. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2012, 48, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humer, A.; Granqvist, K. The gradual city-ness and town-ness of public service locations: Towards spatially sensitive sector policies. Geoforum 2020, 113, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobst, M.; Fischer, T. Approaching a Common Conscious Dataspace from a Data Provider Perspective—Requirements and Perspectives. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2022; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Hendrix, E.M.T., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 333–343. ISBN 978-3-031-10449-7. [Google Scholar]

- StROG 2022—Gesetz vom 23. März 2010 über die Raumordnung in der Steiermark (Steiermärkisches Raumordnungsgesetz), LGBl. Nr. LGBl. Nr. 49/2010 idF LGBl. Nr. 84/22. Available online: https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=LrStmk&Gesetzesnummer=20000069&FassungVom=2023-05-27 (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- BFGG 1993—Bundesgesetz, mit dem ein Pflegegeld Eingeführt wird (Bundespflegegeldgesetz), BGBl. Nr. 110/1993 idF BGBl. I Nr. 213/2022. Available online: https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=10008859&FassungVom=2023-05-27 (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- PFG 2011—Bundesgesetz, mit dem ein Pflegefonds Eingerichtet und ein Zweckzuschuss an Die Länder zur Sicherung und zum Bedarfsgerechten Aus- und Aufbau des Betreuungs- und Pflegedienstleistungsangebotes in der Langzeitpflege für Die Jahre 2011 Bis 2023 Gewährt Wird (Pflegefondsgesetz), BGBl. I Nr. 57/2011 idF BGBl. I Nr. 9/2022. Available online: https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=20007381&FassungVom=2023-05-27 (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Gesamte Rechtsvorschrift für Pflegebedürftige Personen [Bund—Länder]—1993. Vereinbarung Zwischen dem Bund und den Ländern Gemäß Art. 15a B-VG über Gemeinsame Maßnahmen des Bundes und der Länder für Pflegebedürftige Personen Samt Anlagen, BGBl. Nr. 866/1993. Available online: https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=10001280&FassungVom=2023-05-27 (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Tiroler Heim- und Pflegeleistungsgesetz 2005—Gesetz vom 1. Februar 2005 über Heime für Hilfs-, Betreuungs- Oder Pflegebedürftige, Insbesondere ältere, Menschen, LGBl. Nr. 23/2005 idF LGBl Nr. 205/2021. Available online: https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=LrT&Gesetzesnummer=20000318&FassungVom=2023-05-27 (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Penchansky, R.; Thomas, J.W. The concept of access: Definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med. Care 1981, 19, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donabedian, A. Models for Organizing the Delivery of Personal Health Services and Criteria for Evaluating Them. Milbank Meml. Fund Q. 1972, 50, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, D.P. Catchments of general practice in different countries—A literature review. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2014, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalobos Dintrans, P. Do long-term care services match population needs? A spatial analysis of nursing homes in Chile. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, N.; Shen, Z.; Nishino, T. Assessing the Allocation of Special Elderly Nursing Homes in Tokyo, Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaňková, I.; Vavrek, R. Evaluation of local accessibility of homes for seniors using multi-criteria approach—Evidence from the Czech Republic. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 29, e21–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, G.; Langford, M.; Llewellyn, M. Towards an understanding of inequalities in accessing residential and nursing home provision: The role of geographical approaches. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, 2218–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrabková, I.; Ertingerová, I.; Kukuliač, P. Determination of gaps in the spatial accessibility of nursing services for persons over the age of 65 with lowered self-sufficiency: Evidence from the Czech Republic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0244991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyseen, A.K.; Nøhr, C.; Sørensen, E.M.; Gudes, O.; Geraghty, E.M.; Shaw, N.T.; Bivona-Tellez, C. A Review and Framework for Categorizing Current Research and Development in Health Related Geographical Information Systems (GIS) Studies. Yearb. Med. Inform. 2014, 9, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, R.; Devillers, R.; Luther, J.E.; Eddy, B.G. GIS-Based Multiple-Criteria Decision Analysis. Geogr. Compass 2011, 5, 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, J.; Cookson, R.; Sainsbury, R.; Glendinning, C. (Eds.) Jonathan Bradshaw on Social Policy: Selected Writings 1972–2011; University of York: York, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-907265-22-8. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, J.A.; Camfield, L.; Woodcock, A. Needs, Wants and Goals: Wellbeing, Quality of Life and Public Policy. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2009, 4, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, N.; Karbach, U.; Pfaff, H. Bedarfsgerechte Versorgung—Ein Überblick gängiger Definitionen. Public Health Forum 2016, 24, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, J.R. A Taxonomy of Social Need. In Jonathan Bradshaw on Social Policy: Selected Writings 1972–2011; Bradshaw, J., Cookson, R., Sainsbury, R., Glendinning, C., Eds.; University of York: York, UK, 2013; pp. 1–11. ISBN 978-1-907265-22-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hämel, K.; Ewers, M.; Schaeffer, D. Versorgungsgestaltung angesichts regionaler Unterschiede. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 46, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanford, A.M.; Orrell, M.; Tolson, D.; Abbatecola, A.M.; Arai, H.; Bauer, J.M.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Dong, B.; Ga, H.; Goel, A.; et al. An international definition for “nursing home”. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amt der Tiroler Landesregierung. Planungsverbände. Available online: https://www.tirol.gv.at/statistik-budget/statistik/regionsprofile/planungsverbaende/ (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Bundesamt für Eich- und Vermessungswesen—BEV. Kartographisches Modell 1:500 000 Raster Stichtag 1 January 2023. Available online: https://data.bev.gv.at/geonetwork/srv/metadata/a350f1f1-48e2-4798-a6ac-6cac12a32906 (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Österreichische Raumordnungskonferenz (ÖROK). Ergebnisse der ÖREK-Partnerschaft: “Strategien für Regionen mit Bevölkerungsrückgang”. Broschüre der ÖREK-Partnerschaft; Materialien Heft 6; ÖROK: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gemeindeverband Bezirksaltenheime Lienz. Homepage. Available online: https://www.heime-osttirol.at/live/impressum (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Amt der Tiroler Landesregierung. Zentrale Orte in Tirol. Available online: https://www.tirol.gv.at/fileadmin/themen/landesentwicklung/raumordnung/bilder/tiris/zentrale_orte_2010.jpg (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Amt der Tiroler Landesregierung. Zentrale Orte in Tirol. Karte. Available online: https://www.tirol.gv.at/fileadmin/_migrated/content_uploads/zentrale_orte_2010_01.jpg (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Amt der Tiroler Landesregierung. Strukturplan Pflege 2012–2022. Planungsgrundlage für Die Versorgung Betreuungs- und Pflegebedürftiger Personen in Tirol. 2012. Available online: https://www.tirol.gv.at/fileadmin/themen/gesellschaft-soziales/soziales/Publikationen/Evaluierungsbericht_zum_Strukturplan_Pflege_2012_-_2022.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Amt der Tiroler Landesregierung. Strukturplan Pflege 2012–2022. Evaluierungsbericht 2017. Available online: https://www.tirol.gv.at/fileadmin/themen/gesellschaft-soziales/soziales/publikationen/evaluierungsbericht_zum_strukturplan_pflege_2012_-_2022.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Google. Google Maps. Available online: https://www.google.at/maps/preview (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Curry, E. Real-Time Linked Dataspaces; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-29664-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hadley, C. The Global Fundamental Geospatial Data Themes Journey. United Nations Committee of Experts on Global Geospatial Information Management. Available online: http://ggim.un.org/documents/fundamentaldatapublication.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Scott, G.P. A National Strategic Geospatial Information Framework to Support the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Available online: https://minerva-access.unimelb.edu.au/items/fa93bcfd-3331-5012-99e6-4d73580fe850/full (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Bundesamt für Eich- und Vermessungswesen—BEV. Verwaltungsgrenzen (VGD) INSPIRE Stichtag 01.04.2022. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48677/bc4c5cb7-8698-4468-acac-39a114e7914e (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Bundesamt für Eich- und Vermessungswesen—BEV. Serie ALS DTM Höhenraster 1m Stichtag 15.09.2021. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48677/63fd20c5-cd34-4d00-829f-a1fd380f6b4b (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Bundesamt für Eich- und Vermessungswesen—BEV. Digitales Landschaftsmodell—Verkehr Stichtag 25.01.2023. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48677/ed8c11ce-c7e4-4d04-bf33-fcaabbaf1158 (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Bundesamt für Eich- und Vermessungswesen—BEV. Digitales Landschaftsmodell—Bauwerke Stichtag 25.01.2023. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48677/0e36cab1-698a-42a7-b72d-9631d2d7ad28 (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- OpenStreetMap. OSM History Dump© OpenStreetMap Contributors. Available online: https://planet.openstreetmap.org/planet/full-history (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- OpenRouteService. Available online: https://openrouteservice.org (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- QGIS. Available online: https://www.qgis.org/en/site (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Handbook on Governance Statistics (N.D.). Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/HRIndicators/handbook_governance_statistics.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Guidelines on Data Disaggregation for SDG Indicators Using Survey Data. (N.D.). Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cb3253en/cb3253en.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Adressregister. Available online: https://adressregister.gv.at/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesministerium für Finanzen. Höhe des Pflegegeldes. Available online: https://www.oesterreich.gv.at/themen/soziales/pflege/4/seite.360516.html (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Nestorová Dická, J.; Gurová, P. The sustainability of social care in Slovakia: Modelling the existing network of residential social facilities for future senior populations. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2022, 30, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesundheit Österreich GmbH. Österreichisches Gesundheitsinformationssystem. Available online: https://www.goeg.at/OEGIS (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Mathis-Edenhofer, S.; Röthlin, F.; Wachabauer, D.; Haneef, R.; Ventura, I.; Fülöp, G. Regional health care profiles—An improved method for generating case studies on the catchment areas of envisaged primary health care units in Austria: A report to the InfAct Joint Action. Arch. Public Health 2022, 80, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T. Über die Wohnstandortwahl am altersbedingten Ende der Multilokalität und die Konsequenzen für Stadt und Land: Eine Reflexion anhand empirischer Befunde zu Österreich. In Jahrbuch StadtRegion 2021/2022. Stadt-Land-Relationen. Disziplinäre Spurensuchen; Schmidt-Lauber, B., Othengrafen, F., Pohlan, J., Wehrhahn, J., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2022; pp. 89–113. ISBN 978-3-658-38941-3. [Google Scholar]

| Name of Planning Association (PA) | Total Number of Inhabitants (75+ in %) | Comprises Parts of the Following Valleys | Number of Municipalities | Spatial Archetypes of Municipalities | Name, Spatial Archetype and Centrality of LTC-Location Municipality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA Isel Region | 11,542 (9.7) | Virgen Valley, Kalser Valley, Defereggen Valley, Isel Valley | 8 | rural (5 out of 8 peripheral) | Matrei rural low centrality |

| PA East Tyrolean Oberland | 8993 (10.5) | Villgraten Valley, Tyrolean Gail/Lesach Valley | 10 | rural (6 out of 10 peripheral) | Sillian rural, peripheral low centrality |

| PA Valley Bottom of Lienz | 28,283 (11.1) | Isel Valley, Valley Bottom of Lienz | 15 | urban/rural (9 out of 15 urban) | Lienz, Nußdorf-Debant small urban centres intermediate, low centrality |

| Questions | Exact Wording |

|---|---|

| question 1 (Q1) | Is there a significant difference in the number of people who previously lived in Valley Bottom of Lienz now reside in LTC Lienz and LTC Nußdorf-Debant compared to the other LTCs? |

| question 2 (Q2) | Is there a significant difference in the number of people who previously lived in Villgraten Valley now reside in LTC Sillian compared to the other LTCs? |

| question 3 (Q3) | Is there a significant difference in the number of people who previously lived in Tyrolean Gail/Lesach Valley now reside in LTC Sillian compared to the other LTCs? |

| question 4 (Q4) | Is there a significant difference in the number of people who previously lived in Defereggen Valley now reside in LTC Matrei compared to the other LTCs? |

| question 5 (Q5) | Is there a significant difference in the number of people who previously lived in Kalser Valley now reside in LTC Matrei compared to the other LTCs? |

| question 6 (Q6) | Is there a significant difference in the number of people who previously lived in Virgen Valley now reside in LTC Matrei compared to the other LTCs? |

| question 7 (Q7) | Is there a significant difference in the number of people who previously lived in Villgraten Valley as well as in Tyrolean Gail/Lesach now reside in LTC Matrei compared to the other LTCs? |

| question 8 (Q8) | Is there a significant difference in the number of people who previously lived in Defereggen Valley, Kalser Valley and Virgen Valley now reside in LTC Matrei compared to the other LTCs? |

| question 9 (Q9) | Is there a significant difference in the number of people who previously lived in Puster Valley now reside in LTC Sillian and LTC Lienz compared to the other LTCs? |

| question 10 (Q10) | Is there a significant difference in the number of people who previously lived in Isel Valley now reside in LTC Matrei and LTC Lienz compared to the other LTCs? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fischer, T.; Moder, K.; Jobst, M. Appraisal of Provision Structures of Nursing Homes for Old Persons—Illustrated by Cross-Sectional Data for East Tyrol. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14535. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914535

Fischer T, Moder K, Jobst M. Appraisal of Provision Structures of Nursing Homes for Old Persons—Illustrated by Cross-Sectional Data for East Tyrol. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14535. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914535

Chicago/Turabian StyleFischer, Tatjana, Karl Moder, and Markus Jobst. 2023. "Appraisal of Provision Structures of Nursing Homes for Old Persons—Illustrated by Cross-Sectional Data for East Tyrol" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14535. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914535

APA StyleFischer, T., Moder, K., & Jobst, M. (2023). Appraisal of Provision Structures of Nursing Homes for Old Persons—Illustrated by Cross-Sectional Data for East Tyrol. Sustainability, 15(19), 14535. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914535