The Experiential Wine Tourist’s Model: The Case of Gran Canaria Wine Cellar Establishments

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Review of the Literature

3. Methodology

- Indicators on perceived quality of cellar: Seven-point Likert question with four items regarding satisfaction with the cellar’s services, performances and products; this measuring instrument was derived from [67].

- Indicators on destination loyalty: Seven-point Likert question with four items related to destination loyalty to Gran Canaria. The items were selected by considering [64].

- Indicators on socio-demographics: Four dimensions such as a dichotic question for gender, five-point scales for education and age, and a closed question for nationality.

4. Results

Preliminary Analysis

5. Analysis of the Path Model

6. Discussion

- This study discovers that destination loyalty is fundamentally inverse to processing a lot of information and awareness. This maybe follows the observations in [39] because loyalty depends on aesthetic stimuli. Therefore, there is the question of why the lack of cognition favours destination loyalty. Going by the findings in [19], this might be explained by referring to a holistic behavioural response. The answer might lie in passionate nature, whose devotion is always more precognitive and sensorial than rational.

- Nonetheless, this study demonstrates that the ‘wine experience’ is much more than emotional drinking. In fact, it reveals that several variables are irrelevant to the experience of the enotourist, such as emotions, smell, hearing and taste. This contradicts other research works [19]. In contrast, there are two key senses—sight and touch—that give credit to the rural scenery and its physical environment. Therefore, there can be differing accounts of what a good cellar is like, although it is based on more than just the wine and its associated products and services, since the surroundings take centre stage [12].

- In this sense, this study broadens the satisfaction precursors by highlighting the influence of cellar surroundings, which are remotely configured by touch and social interactions. Previous research works neglected this as one of the crucial factors of cellar satisfaction. It is consistent with the evidence that the brand’s name determines loyalty [35].

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- García, D. Acercamiento a la obra periodística de Buenaventura Bonnet Reverón (1883–1951). Cliocanarias 2023, 5, 241–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.; Guedes, E. Enoturismo en un destino del sol y playa. El caso de la bodega Las Tirajanas de gran canaria–España. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2016, 2, 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- Campo, R.; Rosato, P.; Battisti, E. Multisensory analysis and Wine Marketing: Systematic Review and Perspectives. Br. Food J. 2021, 124, 3274–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de Canarias. Canarias, Referencia en la Transición Hacia una Economía Sostenible y Digital a Través del Conocimiento [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://www.cienciacanaria.es/secciones/te-puede-interesar/1281-canarias-referencia-en-la-transicion-hacia-una-economia-sostenible-y-digital-a-traves-del-conocimiento (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- United Nations. Home—United Nations Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, A.; Sousa, B.; Santos, V.; Ramos, P.; Madeira, A. Wine tourism and sustainability awareness: A consumer behavior perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachao, S.; Breda, Z.; Fernandes, C.; Joukes, V. Food and wine experiences towards co-creation in tourism. Tour. Rev. 2019, 76, 1050–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Qiu, H.; King, B.; Huang, S. Understanding the wine tourism experience: The roles of facilitators, constraints, and involvement. J. Vacat. Mark. 2020, 26, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Goodman, S.; Bruwer, J.; Cohen, J. Beyond better wine: The impact of experiential and monetary value on wine tourists’ loyalty intentions. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, P.J. A review of global wine tourism research. J. Wine Res. 2004, 15, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.K.; Dixit, S.K. The growth and evolution of global wine tourism. In Routledge Handbook of Wine Tourism; En Dixit, S.K., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D.; Brown, G. Critical success factors for wine tourism regions: A demand analysis. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Ben-Nun, L. The important dimensions of wine tourism experience from potential visitors’ perception. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 9, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, A.; Correia, A.; Filipe, J.A. Modelling wine tourism experiences. Anatolia 2019, 30, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, A.; Correia, A.; Filipe, J.A. Wine Tourism: Constructs of the Experience. In Trends in Tourist Behavior; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kastenholz, E.; Cunha, D.; Eletxigerra, A.; Carvalho, M.; Silva, I. The Experience Economy in a Wine Destination—Analysing Visitor Reviews. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leckie, C.; Nyadzayo, M.W.; Johnson, L.W. Antecedents of consumer brand engagement and brand loyalty. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 558–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.D.; Liu, Y. Old wine region, new concept and sustainable development: Winery entrepreneurs’ perceived benefits from wine tourism on Spain’s Canary Islands. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 991–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.R.; Ramos, P.; Almeida, N.; Santos-Pavón, E. Wine and wine tourism experience: A theoretical and conceptual review. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2019, 11, 718–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.; Ramos, P.; Almeida, N.; Santos-Pavón, E. Developing a wine experience scale: A new strategy to measure holistic behaviour of wine tourists. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkemaat, B.; Peters, M.; Boksberger, P.; Secco, M. The staging of experiences in wine tourism. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamarreño, G.; Cruz, E.; Hernando, C. La digitalización de la experiencia enoturística: Una revisión de la literatura y aplicaciones prácticas. Doxa Comun. 2021, 33, 257–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Carmona, D.; Paramio, A.; Cruces-Montes, S.; Marín-Dueñas, P.; Aguirre Montero, A.; Romero-Moreno, A. The effect of the wine tourism experience. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 29, 100793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi-Valbona, M.; Mascarilla-Miró, O. Wine lovers: Their interés in tourist experiences. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 14, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, T.; Cruz, M. Dimensions and outcomes of experience quality in tourism: The case of Port wine cellars. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priilaid, D.; Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J. A blue ocean strategy for developing visitor wine experiences: Unlocking value in the Cape region tourism market. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, C.; Hess-Misslin, I.; Mereaux, J. Aesthetics and conviviality as key factors in a successful wine tourism experience. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2021, 33, 176–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. Multisensory experiential wine marketing. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 71, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado, A.; Stoleriu, O.; Lupu, C. Wine tourism: A multisensory experience. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Martín, S.; González-Benito, O.; Martos-Partal, M. To what extent does need for touch affect online perceived quality? Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2017, 45, 950–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Q.; Spence, C. A smooth wine? Haptic influences on wine evaluation. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2018, 14, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Sparks, B.; Coghlan, A. Event experiences through the lens of attendees. Event Manag. 2017, 21, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumawati, A.; Rahayu, K.S. The effect of experience quality on customer perceived value and customer satisfaction and its impact on customer loyalty. TQM J. 2020, 32, 1525–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, J. Global Wine Tourism: Research, Management and Marketing; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, C. Consumer brand loyalty in the Chilean wine industry. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2015, 21, 442–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drennan, J.; Bianchi, C.; Cacho-Elizondo, S.; Louriero, S.; Guibert, N.; Proud, W. Examining the role of wine brand love on brand loyalty: A multi-country comparison. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 49, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charters, S.; Ali-Knight, J. Wine Tourism—A Thirst for Knowledge? Int. J. Wine Mark. 2000, 12, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Zeng, A.; Fang, Z. The art of flavored wine: Tradition and future. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 130–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadri-Felitti, D.L.; Fiore, A.M. Destination loyalty: Effects of wine tourists’ experiences, memories, and satisfaction on intentions. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2013, 13, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festa, G.; Cuomo, M.T.; Metallo, G.; Festa, A. The (r)evolution of wine marketing mix: From the 4Ps to the 4Es. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1550–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachao, S.; Breda, Z.; Fernandes, C.; Joukes, V. Drivers of experience co-creation in food and wine tourism: An exploratory quantitative analysis. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.; Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M. Co-creative tourism experiences: A conceptual framework and its application to food & wine tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 48, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Soliha, E.; Aquinia, A.; Hayuningtias, K.A.; Ramadhan, K.R. The influence of experiential marketing and location on customer loyalty. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 1327–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Agipot, D.; Mendes, J.; Valle, P. Exploring the conceptualization of the sensory dimension of tourist experiences. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 62–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kirillova, K.; Fu, X.; Lehto, X.; Cai, L. What makes a destination beautiful? Dimensions of tourist aesthetic Judgment. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, B. Understanding the wine tourism experience for winery visitors in the Niagara region, Ontario, Canada. Tour. Geogr. 2005, 7, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espejel, J.; Fandos, C. Wine marketing strategies in Spain: A structural equation approach to consumer response to protected designations of origin (PDOs). Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M. Turismo experiencial y gestión estratégica de recursos patrimoniales: Un estudio exploratorio de percepción de productos turísticos en las Sierras Subbéticas cordobesas (Andalucia). Scr. Nova Rev. Eletrónica Geogr. 2015, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Liang, L. Examining the effect of potential tourits’ wine product involvement on wine tourism destination image and travel intention. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D.; Dean, D.; Chen, B.T.; Kusdibyo, L. Tourist experience with agritourism attractions: What leads to loyalty? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 45, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeiwaah, E.; Otoo, F.E.; Suntikul, W.; Huang, W.J. Understanding culinary tourist motivation, experience, satisfaction, and loyalty using a structural approach. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Kladou, S.; Usakli, A.; Shi, Y. Inspiring winery experiences to benefit destination branding? Insights from wine tourists at Yantai, China. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2020, 5, 116–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, W. Analysis of the wine experience tourism based on experience economy: A case for Changyu wine tourism in China. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2013, 5, 925–4930. [Google Scholar]

- Saayman, M.; Van Der Merwe, A. Factors determining visitors’ memorable wine-tasting experience at wineries. Anatolia 2015, 26, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asero, V.; Patti, S. Wine tourism experience and consumer behavior: The case of Sicily. Tour. Anal. 2011, 16, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R.; O’Mahony, B. On the trail of food and wine: The tourist search for meaningful experience. Ann. Leis. Res. 2007, 10, 498–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Alant, K. The hedonic nature of wine tourism consumption: An experiential view. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinamiza Asesores. Informe Sobre el Enoturista en las Rutas del Vino de España [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://dinamizaasesores.es/observatorio-rutas-del-vino-de-espana/ (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Torabi, A.; Hamidi, H.; Safaie, N. Effect of Sensory Experience on Customer Word-of-mouth Intention, Considering the Roles of Customer Emotions, Satisfaction, and Loyalty. Int. J. Eng. 2021, 34, 682–699. [Google Scholar]

- Tanford, S.; Montgomery, R.; Hertzman, J. Towards a model of wine event loyalty. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2012, 13, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, B.; Arcodia, C.; Ma, E.; Hsiao, A. Understanding wine tourism in China using an integrated product-level and experience economy framework. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 949–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zheng, Y. The Influence of Tourism Image and Activities Appeal on Tourist Loyalty—A Study of Tainan City in Taiwan. J. Manag. Strategy 2014, 5, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.S.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, C.K. Measuring festival quality and value affecting visitors’ satisfaction and loyalty using a structural approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Chang, Y.S. The influence of experiential marketing and activity involvement on the loyalty intentions of wine tourists in Taiwan. Leis. Stud. 2012, 31, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Coode, M.; Saliba, A.; Herbst, F. Wine tourism experience effects of the tasting room on consumer brand loyalty. Tour. Anal. 2013, 18, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Mogollón, J.M.; Di-Clemente, E.; Campón-Cerro, A.M. Culinary travel experiences, quality of life and loyalty. Span. J. Mark.-ESIC 2020, 24, 425–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, M.; Charters, S. Survey Timing and Visitor Perceptions of Cellar Door Quality. In Global Wine Tourism: Research, Management and Marketing; Carlsen, J., Charters, S., Eds.; CABI Pub: Wallingford, UK, 2006; pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar]

| ITEMS | EFA | CFA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | SRW | |

| There is interesting information about this wine at my disposal | 0.729 | 0.890 | 0.082 | 10.910 | *** | 0.707 |

| This wine has its own features and identity | 0.845 | 0.822 | 0.063 | 13.085 | *** | 0.773 |

| It is a traditional and technical product | 0.773 | 0.689 | 0.066 | 10.507 | *** | 0.659 |

| I would like to know this wine better | 0.715 | 0.806 | 0.078 | 10.272 | *** | 0.644 |

| This wine has been made with wisdom | 0.855 | 1.000 | 0.834 | |||

| This wine is interesting | 0.821 | 0.916 | 0.067 | 13.710 | *** | 0.833 |

| ||||||

| EFA | ||||||

| Explained Variance: 62.659%; KMO: 0.867; Bartlett: 653.735; Degree of Freedom: 15; Sig. 0.000; Cronbach’s Alpha: 0.876. (***: statistical outliers) | ||||||

| CFA | ||||||

| Chi cuadrado: 10.197; GL: 7; p: 0.178; GFI: 0.984; RMSEA: 0.045; AGFI: 0.953; NFI: 0.985; RFI: 0.967; IFI: 0.995; TLI: 0.989; CFI: 0.995; CMIN/DF: 1.457; PGFI: 0.328; PNFI: 0.459. Composite Reliability: 0.8814; Extracted Variance: 0.5559. | ||||||

| ITEMS | EFA | CFA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | SRW | |

| This wine is happy | 0.860 | 0.949 | 0.069 | 13.696 | *** | 0.793 |

| This wine is surprising | 0.828 | 0.848 | 0.068 | 12.455 | *** | 0.745 |

| This wine helps to make feel well and happy | 0.875 | 1.000 | 0.857 | |||

| I’m proud of trying this wine | 0.840 | 1.075 | 0.077 | 13.990 | *** | 0.800 |

| It’s a pleasure to taste this wine | 0.851 | 0.941 | 0.064 | 14.590 | *** | 0.823 |

| ||||||

| EFA | ||||||

| Explained Variance: 72.437%; KMO: 0.885; Bartlett: 665.436; DofF: 10; Sig. 0.000; Cronbach’s Alpha: 0.903. (***: statistical outliers) | ||||||

| CFA | ||||||

| Chi cuadrado: 1.862; GL: 4; p: 0.761; GFI: 0.997; RMSEA: 0.000; AGFI: 0.988; NFI: 0.997; RFI: 0.993; IFI: 1.003; TLI: 1.008; CFI: 1.000; CMIN/DF: 0.465; PGFI: 0.266; PNFI: 0.399. Composite Reliability: 0.9014; Extracted Variance: 0.6470. | ||||||

| ITEMS | EFA | CFA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | SRW | |

| I’ve got a different experience, thanks to this wine | 0.699 | 0.658 | 0.073 | 8.972 | *** | 0.595 |

| This wine might match with many dishes | 0.798 | 0.775 | 0.070 | 11.036 | *** | 0.667 |

| This wine might be drunk without anything else | 0.835 | 1.118 | 0.072 | 15.636 | *** | 0.864 |

| This wine might be suitable for many occasions | 0.881 | 1.000 | 0.889 | |||

| The wine price is right | 0.799 | 0.980 | 0.080 | 12.254 | *** | 0.708 |

| ||||||

| EFA | ||||||

| Explained Variance: 64.744%; KMO: 0.797; Bartlett: 543.034; DofF: 10; Sig. 0.000; Cronbach’s Alpha: 0.860. (***: statistical outliers) | ||||||

| CFA | ||||||

| Chi cuadrado: 4.766; GL: 3; p: 0.190; GFI: 0.992; RMSEA: 0.052; AGFI: 0.958; NFI: 0.991; RFI: 0.971; IFI: 0.997; TLI: 0.989; CFI: 0.997; CMIN/DF: 1.589; PGFI: 0.198; PNFI: 0.297. Composite Reliability: 0.8651; Extracted Variance: 0.5676. | ||||||

| ITEMS | EFA | CFA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comp. | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | SRW | |

| The staff are high quality professionals | 0.869 | 0.662 | 0.069 | 9.611 | *** | 0.620 |

| The staff treat with courtesy and are pleasant | 0.939 | 1.000 | 0.865 | |||

| The staff are diligent and responsible | 0.942 | 0.964 | 0.070 | 13.681 | *** | 0.834 |

| The staff are helpful | 0.903 | 0.809 | 0.066 | 12.189 | *** | 0.749 |

| ||||||

| EFA | ||||||

| Explained Variance: 83.479%; KMO: 0.853; Bartlett: 778.066; DofF: 6; Sig. 0.000; Cronbach’s Alpha: 0.933. (***: statistical outliers) | ||||||

| CFA | ||||||

| Chi cuadrado: 0.647; GL: 2; p: 0.724; GFI: 0.999; RMSEA: 0.000; AGFI: 0.993; NFI: 0.999; RFI:.998; IFI: 1.002; TLI: 1.005; CFI: 1.000; CMIN/DF: 0.323; PGFI: 0.200; PNFI: 0.333. Composite Reliability: 0.9349; Extracted Variance: 0.7828. | ||||||

| ITEMS | EFA | CFA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comp. | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | SRW | |

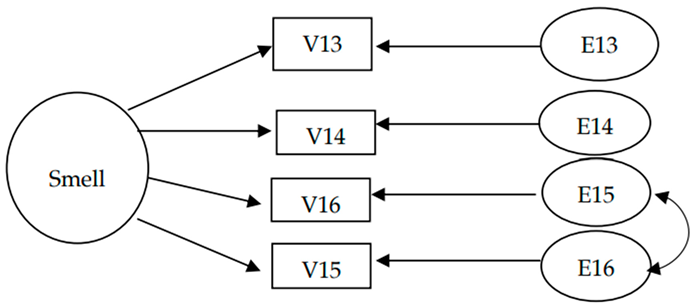

| I like this wine’s smell | 0.880 | 1.010 | 0.066 | 15.257 | *** | 0.860 |

| I perceive a nice bouquet from the wine | 0.886 | 1.000 | 0.869 | |||

| The smell of this wine invites to drink it | 0.882 | 0.991 | 0.072 | 13.755 | *** | 0.800 |

| It is a wine with fragrance | 0.857 | 0.867 | 0.069 | 12.612 | *** | 0.756 |

| ||||||

| EFA | ||||||

| Explained Variance: 76.824%; KMO: 0.834; Bartlett: 536.815; DofF: 6; Sig. 0.000; Cronbach’s Alpha: 0.899. (***: statistical outliers) | ||||||

| CFA | ||||||

| Chi cuadrado: 0.289; GL: 1; p: 0.593; GFI: 0.999; RMSEA: 0.000; AGFI: 0.994; NFI: 0.999; RFI:0.997; IFI: 1.001; TLI: 1.008; CFI: 1.000; CMIN/DF: 0.286; PGFI: 0.100; PNFI: 0.167. Composite Reliability: 0.8929; Extracted Variance: 0.6765. | ||||||

| ITEMS | EFA | CFA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comp. | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | SRW | |

| The wine is nice and delicious | 0.878 | 0.899 | 0.057 | 15.776 | *** | 0.831 |

| The wine tastes very well | 0.905 | 1.000 | 0.892 | |||

| I like how taste this wine | 0.895 | 0.979 | 0.058 | 16.861 | *** | 0.870 |

| The taste of this wine has insightful details | 0.746 | 0.690 | 0.067 | 10.322 | *** | 0.627 |

| ||||||

| EFA | ||||||

| Explained Variance: 73.671%; KMO: 0.824; Bartlett: 500.813; DofF: 6; Sig. 0.000; Cronbach’s Alpha: 0.879. (***: statistical outliers) | ||||||

| CFA | ||||||

| Chi cuadrado: 0.040; GL: 2; p: 0.980; GFI: 1.000; RMSEA: 0.000; AGFI: 1.000; NFI: 1.000; RFI:1.000; IFI: 1.004; TLI: 1.012; CFI: 1.000; CMIN/DF: 0.020; PGFI: 0.200; PNFI: 0.333. Composite Reliability: 0.8538; Extracted Variance: 0.5972. | ||||||

| ITEMS | EFA | CFA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comp. | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | SRW | |

| If this wine had a voice, it would sound good | 0.850 | 0.887 | 0.063 | 14.155 | *** | 0.832 |

| If this wine were music, it would sound well | 0.893 | 1.000 | 0.940 | |||

| The wine’s name sounds well | 0.830 | 0.756 | 0.072 | 10.455 | *** | 0.649 |

| It is a pleasure to listen how this wine is poured | 0.829 | 0.835 | 0.077 | 10.854 | *** | 0.667 |

| ||||||

| EFA | ||||||

| Explained Variance: 72.357%; KMO: 0.760; Bartlett: 479.020; DofF: 6; Sig. 0.000; Cronbach’s Alpha: 0.869. (***: statistical outliers) | ||||||

| CFA | ||||||

| Chi cuadrado: 3.994; GL: 1; p: 0.046; GFI: 0.991; RMSEA: 0.116; AGFI: 0.991; NFI: 0.992; RFI:.950; IFI: 0.994; TLI: 0.962; CFI: 0.994; CMIN/DF: 3.994; PGFI: 0.099; PNFI: 0.165. Composite Reliability: 0.8595; Extracted Variance: 0.6104. | ||||||

| ITEMS | EFA | CFA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comp. | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | SRW | |

| The temperature of this wine is appropriate | 0.740 | 0.662 | 0.069 | 9.611 | *** | 0.620 |

| The wine has a charming body | 0.884 | 1.000 | 0.865 | |||

| The wine has a cozy texture | 0.865 | 0.964 | 0.070 | 13.681 | *** | 0.834 |

| The wine density is balanced | 0.830 | 0.809 | 0.066 | 12.189 | *** | 0.749 |

| ||||||

| EFA | ||||||

| Explained Variance: 69.178%; KMO: 0.800; Bartlett: 392.346; DofF: 6; Sig. 0.000; Cronbach’s Alpha: 0.851.(***: statistical outliers) | ||||||

| CFA | ||||||

| Chi cuadrado: 3.352; GL: 2; p: 0.187; GFI: 0.993; RMSEA: 0.055; AGFI: 0.964; NFI: 0.992; RFI:.975; IFI: 0.997; TLI: 0.990; CFI: 0.997; CMIN/DF: 1.676; PGFI: 0.199; PNFI: 0.331. Composite Reliability: 0.8538; Extracted Variance: 0.5972. | ||||||

| ITEMS | EFA | CFA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comp. | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | SRW | |

| The wine’s light is nice | 0.847 | 0.826 | 0.068 | 12.215 | *** | 0.738 |

| The wine’s color is appropriate | 0.849 | 0.801 | 0.065 | 12.318 | *** | 0.742 |

| The wine brilliance is pretty | 0.891 | 1.000 | 0.893 | |||

| The wine appearance is sensational | 0.864 | 10.026 | 0.071 | 14.487 | *** | 0.833 |

| ||||||

| EFA | ||||||

| Explained Variance: 74.448%; KMO: 0.823; Bartlett: 483.642; DofF: 6; Sig. 0.000; Cronbach’s Alpha: 0.885. (***: statistical outliers) | ||||||

| CFA | ||||||

| Chi cuadrado: 0.071; GL: 1; p: 0.790; GFI: 1.000; RMSEA: 0.000; AGFI: 0.998; NFI: 1.000; RFI:.999; IFI: 1.002; TLI: 1.012; CFI: 1.000; CMIN/DF: 0.071; PGFI: 0.100; PNFI: 0.167. Composite Reliability: 0.8790; Extracted Variance: 0.6465. | ||||||

| ITEMS | EFA | CFA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comp. | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | SRW | |

| There is a high quality service | 0.858 | 0.887 | 0.061 | 14.439 | *** | 0.766 |

| The offer is good | 0.892 | 1.106 | 0.062 | 17.746 | *** | 0.920 |

| The products on offer are attractive and interesting | 0.913 | 1.000 | 0.893 | |||

| This place has a good atmosphere | 0.729 | 0.674 | 0.067 | 10.058 | *** | 0.641 |

| ||||||

| EFA | ||||||

| Explained Variance: 72.444%; KMO: 0.775; Bartlett: 508.125, DofF: 6, Sig. 0.000; Cronbach’s Alpha: 0.872 (***: statistical outliers) | ||||||

| CFA | ||||||

| Chi cuadrado: 1.961; GL: 1; p: 0.161; GFI: 0.996; RMSEA: 0.066; AGFI: 0.956; NFI: 0.996; RFI:0.977; IFI: 0.998; TLI: 0.989; CFI: 0.998; CMIN/DF: 1.961; PGFI: 0.100; PNFI: 0.166. Composite Reliability: 0.8842; Extracted Variance: 0.6606 | ||||||

| ITEMS | EFA | CFA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comp. | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | SRW | |

| The surroundings area is charm | 0.901 | 0.992 | 0.051 | 19.607 | *** | 0.919 |

| The cellar surrounding is enjoyable | 0.904 | 1.000 | 0.925 | |||

| The surroundings enriches the wine and cellar ambiance | 0.887 | 0.825 | 0.058 | 14.220 | *** | 0.753 |

| Place and shop matches each other | 0.869 | 0.830 | 0.063 | 13.191 | *** | 0.720 |

| ||||||

| EFA | ||||||

| Explained Variance: 79.288%; KMO: 0.784; Bartlett: 664.631, DofF: 6, Sig. 0.000; Cronbach’s Alpha: 0.912 (***: statistical outliers) | ||||||

| CFA | ||||||

| Chi cuadrado: 1.091; GL: 1; p: 0.296; GFI: 0.998; RMSEA: 0.020; AGFI: 0.975; NFI: 0.998; RFI:0.990; IFI: 1.000; TLI: 0.999; CFI: 1.000; CMIN/DF: 1.091; PGFI: 0.100; PNFI: 0.166. Composite Reliability:0.9006; Extracted Variance: 0.6964 | ||||||

| ITEMS | EFA | CFA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comp. | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | SRW | |

| I would like to come back to Gran Canaria | 0.893 | 1.000 | 0.885 | |||

| I would recommend Gran Canaria | 0.884 | 0.789 | 0.053 | 14.807 | *** | 0.858 |

| I would like to become a special visitor of this destination | 0.731 | 0.873 | 0.091 | 9.590 | *** | 0.607 |

| I’m satisfied with Gran Canaria | 0.814 | 0.761 | 0.063 | 12.172 | *** | 0.727 |

| ||||||

| EFA | ||||||

| Explained Variance: 69.398%; KMO: 0.800; Bartlett: 408.028, DofF: 6, Sig. 0.000; Cronbach’s Alpha: 0.831 (***: statistical outliers) | ||||||

| CFA | ||||||

| Chi cuadrado: 0.444; GL: 2; p: 0.801; GFI: 0.999; RMSEA: 0.000; AGFI: 0.995; NFI: 0.999; RFI:0.997; IFI: 1.004; TLI: 1.011; CFI: 1.000; CMIN/DF: 0.222; PGFI: 0.200; PNFI: 0.333 Composite Reliability: 0.8566; Extracted Variance: 0.6040 | ||||||

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | SRW | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SURROUNDINGS | ← | ACTIVITIES | 0.062 | 0.080 | 0.773 | 0.439 | 0.062 |

| SURROUNDINGS | ← | EMOTIONS | 0.005 | 0.091 | 0.051 | 0.959 | 0.005 |

| SURROUNDINGS | ← | COGNITIONS | 0.104 | 0.083 | 1.253 | 0.210 | 0.104 |

| SURROUNDINGS | ← | SIGHT | −0.046 | 0.095 | −0.486 | 0.627 | −0.046 |

| SURROUNDINGS | ← | SOUND | −0.131 | 0.094 | −1.388 | 0.165 | −0.131 |

| SURROUNDINGS | ← | TOUCH | 0.319 | 0.091 | 3.522 | *** | 0.319 |

| SURROUNDINGS | ← | TASTE | −0.026 | 0.094 | -0.277 | 0.782 | −0.026 |

| SURROUNDINGS | ← | SMELL | 0.040 | 0.085 | 0.469 | 0.639 | 0.040 |

| SURROUNDINGS | ← | STAFF INTERACTIONS | 0.447 | 0.066 | 6.717 | *** | 0.447 |

| CELLAR SATISFACTION | ← | ACTIVITIES | 0.296 | 0.069 | 4.283 | *** | 0.296 |

| CELLAR SATISFACTION | ← | EMOTIONS | −0.063 | 0.078 | −0.804 | 0.422 | −0.063 |

| CELLAR SATISFACTION | ← | COGNITIONS | 0.069 | 0.072 | 0.967 | 0.334 | 0.069 |

| CELLAR SATISFACTION | ← | SIGHT | 0.153 | 0.082 | 1.866 | 0.062 | 0.153 |

| CELLAR SATISFACTION | ← | SOUND | −0.065 | 0.081 | −0.798 | 0.425 | −0.065 |

| CELLAR SATISFACTION | ← | TOUCH | −0.057 | 0.080 | −0.716 | 0.474 | −0.057 |

| CELLAR SATISFACTION | ← | TASTE | −0.035 | 0.081 | −0.426 | 0.670 | −0.035 |

| CELLAR SATISFACTION | ← | SMELL | 0.059 | 0.073 | 0.810 | 0.418 | 0.059 |

| CELLAR SATISFACTION | ← | STAFF INTERACTIONS | 0.293 | 0.063 | 4.667 | *** | 0.293 |

| CELLAR SATISFACTION | ← | SURROUNDINGS | 0.290 | 0.058 | 5.015 | *** | 0.290 |

| LOYALTY | ← | ACTIVITIES | 0.004 | 0.086 | 0.043 | 0.966 | 0.004 |

| LOYALTY | ← | STAFF INTERACTIONS | 0.204 | 0.083 | 2.463 | 0.014 | 0.204 |

| LOYALTY | ← | COGNITIONS | −0.248 | 0.087 | −2.837 | 0.005 | −0.248 |

| LOYALTY | ← | SIGHT | 0.014 | 0.104 | 0.129 | 0.897 | 0.014 |

| LOYALTY | ← | SOUND | 0.060 | 0.103 | 0.580 | 0.562 | 0.060 |

| LOYALTY | ← | TOUCH | −0.074 | 0.101 | −0.736 | 0.462 | −0.074 |

| LOYALTY | ← | TASTE | 0.124 | 0.100 | 1.237 | 0.216 | 0.124 |

| LOYALTY | ← | SMELL | 0.165 | 0.090 | 1.820 | 0.069 | 0.165 |

| LOYALTY | ← | CELLAR SATISFACTION | 0.291 | 0.085 | 3.432 | *** | 0.291 |

| LOYALTY | ← | SURROUNDINGS | 0.103 | 0.077 | 1.341 | 0.180 | 0.103 |

| ABSOLUTE INDICATORS: Chi-squared = 1.150; D. of free = 1; Prob L. 284; GFI = 0.999; RMSEA = 0.026 INCREMENTAL INDICATORS: AGFI = 0.933; NFI = 0.999; IFI = 1.000; RFI = 963; CFI = 1.000 PARSIMONIOUS INDICATORS: PNFI = 0.015; AIC = 155.150 (***: statistical outliers) | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Díaz-Meneses, G.; Amador-Marrero, M. The Experiential Wine Tourist’s Model: The Case of Gran Canaria Wine Cellar Establishments. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14551. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914551

Díaz-Meneses G, Amador-Marrero M. The Experiential Wine Tourist’s Model: The Case of Gran Canaria Wine Cellar Establishments. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14551. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914551

Chicago/Turabian StyleDíaz-Meneses, Gonzalo, and Maica Amador-Marrero. 2023. "The Experiential Wine Tourist’s Model: The Case of Gran Canaria Wine Cellar Establishments" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14551. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914551