Narrative or Logical? The Effects of Information Format on Pro-Environmental Behavior

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Information Provision in Energy and Environmental Fields

2.2. Dual-Process Theory and Information Format

2.3. Information Provision by Narrative

3. Method

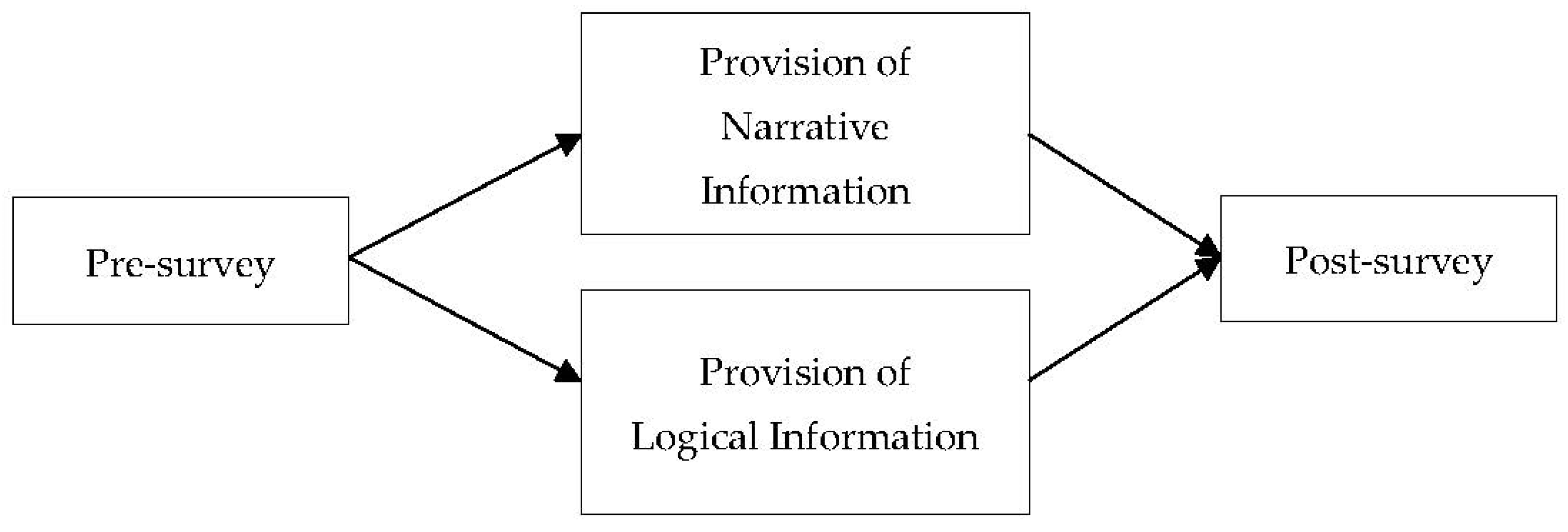

3.1. Participants and Design

3.2. Materials and Methods

3.3. Quantification

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Narrative versus Logical

4.2. Influence of Personal Traits on Behavioral Intention and Policy Acceptance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Glasgow Climate Pact. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cop26_auv_2f_cover_decision.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Iweka, O.; Liu, S.; Shukla, A.; Yan, D. Energy and behaviour at home: A review of intervention methods and practices. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 57, 101238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kreuter, M.W.; Green, M.C.; Cappella, J.N.; Slater, M.D.; Wise, M.E.; Storey, D.; Clark, E.M.; O’Keefe, D.J.; Erwin, D.O.; Holmes, K.; et al. Narrative communication in cancer prevention and control: A framework to guide research and application. Ann. Behav. Med. 2007, 33, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hinyard, L.J.; Kreuter, M.W. Using narrative communication as a tool for health behavior change: A conceptual, theoretical, and empirical overview. Health Educ. Behav. 2007, 34, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.S. One or many? The influence of episodic and thematic climate change frames on policy preferences and individual behavior change. Sci. Commun. 2011, 33, 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moezzi, M.; Janda, K.B.; Rotmann, S. Using stories, narratives, and storytelling in energy and climate change research. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 31, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, B.S.; Chrysochou, P.; Christensen, J.D.; Orquin, J.L.; Barraza, J.; Zak, P.J.; Mitkidis, P. Stories vs. facts: Triggering emotion and action-taking on climate change. Clim. Chang. 2019, 154, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Chiang, Y.; Ng, E.; Lo, J. Using the Norm Activation Model to Predict the Pro-Environmental Behaviors of Public Servants at the Central and Local Governments in Taiwan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashouri, M.; Fung, B.C.M.; Haghighat, F.; Yoshino, H. Systematic approach to provide building occupants with feedback to reduce energy consumption. Energy 2020, 194, 116813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleich, J.; Klobasa, M.; Gölz, S.; Brunner, M. Effects of feedback on residential electricity demand—Findings from a field trial in Austria. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podgornik, A.; Sucic, B.; Blazic, B. Effects of customized consumption feedback on energy efficient behaviour in low-income households. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 130, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benders, R.M.J.; Kok, R.; Moll, H.C.; Wiersma, G.; Noorman, K.J. New approaches for household energy conservation—In search of personal household energy budgets and energy reduction options. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 3612–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallett, R.K.; Melchiori, K.J.; Strickroth, T. Self-confrontation via a carbon footprint calculator increases guilt and support for a proenvironmental group. Ecopsychology 2013, 5, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruqui, A.; Sergici, S.; Sharif, A. The impact of informational feedback on energy consumption—A survey of the experimental evidence. Energy 2010, 35, 1598–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Estrada, M.; Schmitt, J.; Sokoloski, R.; Silva-Send, N. Using in-home displays to provide smart meter feedback about household electricity consumption: A randomized control trial comparing kilowatts, cost, and social norms. Energy 2015, 90, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gangale, F.; Mengolini, A.; Onyeji, I. Consumer engagement: An insight from smart grid projects in Europe. Energy Policy 2013, 60, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, I.; Nekmahmud, M.; Fekete-Farkas, M. How Do Environmental Knowledge, Eco-Label Knowledge, and Green Trust Impact Consumers’ Pro-Environmental Behaviour for Energy-Efficient Household Appliances? Sustainability 2022, 14, 6513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azoumah, Y.K.; Tossa, A.K.; Dake, R.A. Towards a labelling for green energy production units: Case study of off-grid solar PV systems. Energy 2020, 208, 118149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzle, S.L.; Wüstenhagen, R. Dynamic adjustment of eco-labeling schemes and consumer choice—The revision of the EU energy label as a missed opportunity? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2012, 21, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eby, B.; Carrico, A.R.; Truelove, H.B. The influence of environmental identity labeling on the uptake of pro-environmental behaviors. Clim. Chang. 2019, 155, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emberger-Klein, A.; Menrad, K. The effect of information provision on supermarket consumers’ use of and preferences for carbon labels in Germany. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Anderson, K.; Lee, S.H. An energy-cyber-physical system for personalized normative messaging interventions: Identification and classification of behavioral reference groups. Appl. Energy 2020, 260, 114237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.-J.; Yeh, C.-C. The Influence of Competency-Based VR Learning Materials on Students’ Problem-Solving Behavioral Intentions—Taking Environmental Issues in Junior High Schools as an Example. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chen, C.; Lan, J. Direct Expression or Indirect Transmission? An Empirical Research on the Impacts of Explicit and Implicit Appeals in Green Advertising. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saracevic, S.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Wu, T. How normative appeals influence pro-environmental behavior: The role of individualism and collectivism. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 344, 131086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacucci, G.; Spagnolli, A.; Gamberini, L.; Chalambalakis, A.; Bjoerksog, C.; Bertoncini, M.; Torstensson, C.; Monti, P. Designing effective feedback of electricity consumption for mobile user interfaces. Psychnol. J. 2009, 7, 265–289. [Google Scholar]

- Morganti, L.; Pallavicini, F.; Cadel, E.; Candelieri, A.; Archetti, F.; Mantovani, F. Gaming for Earth: Serious games and gamification to engage consumers in pro-environmental behaviours for energy efficiency. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 29, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhew, J.; Pahl, S.; Auburn, T.; Goodhew, S. Making heat visible: Promoting energy conservation behaviors through thermal imaging. Environ. Behav. 2015, 47, 1059–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evans, J.S. Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strack, F.; Deutsch, R. Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 8, 220–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schneider, W.; Shiffrin, R.M. Controlled and automatic human information processing: I. Detection, search, and attention. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 1–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 19, 123–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiken, S. Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 752–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, A.; Sanders, J.; Hoeken, H. Characteristics of narrative interventions and health effects: A review of the content, form, and context of narratives in health-related narrative persuasion research. Rev. Commun. Res. 2016, 4, 88–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornikx, J. A review of experimental research on the relative persuasiveness of anecdotal, statistical, causal, and expert evidence. Stud. Commun. Sci. 2005, 5, 205–216. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop, S.M.; Wakefield, M.; Kashima, Y. Pathways to persuasion: Cognitive and experiential responses to health-promoting mass media messages. Commun. Res. 2010, 37, 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falzon, C.; Radel, R.; Cantor, A.; d’Arripe-Longueville, F. Understanding narrative effects in physical activity promotion: The influence of breast cancer survivor testimony on exercise beliefs, self-efficacy, and intention in breast cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkey, L.K.; Lopez, A.M.; Minnal, A.; Gonzalez, J. Storytelling for promoting colorectal cancer screening among underserved Latina women: A randomized pilot study. Cancer Control 2009, 16, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banerjee, S.C.; Greene, K. Examining narrative transportation to anti-alcohol narratives. J. Subst. Use 2013, 18, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, K.; Campo, S.; Banerjee, S.C. Comparing normative, anecdotal, and statistical risk evidence to discourage tanning bed use. Commun. Q. 2010, 58, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.H.; Green, M.C.; Kohler, C.; Allison, J.J.; Houston, T.K. Stories to communicate risks about tobacco: Development of a brief scale to measure transportation into a video story—The ACCE Project. Health Educ. J. 2011, 70, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.C.; Brock, T.C. The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Defining identification: A theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. Mass Commun. Soc. 2001, 4, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tal-Or, N.; Cohen, J. Understanding audience involvement: Conceptualizing and manipulating identification and transportation. Poetics 2010, 38, 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, M.D.; Rouner, D. Entertainment–education and elaboration likelihood: Understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Commun. Theor. 2002, 12, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J.E.; Moore, M.C.; Britton, J.E. Fishing for feelings? Hooking viewers helps! J. Consum. Psychol. 2004, 14, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Laer, T.; de Ruyter, K.; Visconti, L.M.; Wetzels, M. The extended transportation-imagery model: A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of consumers’ narrative transportation. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 40, 797–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aarøe, L. Investigating frame strength: The case of episodic and thematic frames. Polit. Commun. 2011, 28, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, K. Framing persuasive appeals: Episodic and thematic framing, emotional response, and policy opinion. Polit. Psychol. 2008, 29, 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, A.L. Human interest or hard numbers? Experiments on citizens’ selection, exposure, and recall of performance information, Public Adm. Rev. 2017, 77, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, R.J.; Mullinix, K.J. Framing innocence: An experimental test of the effects of wrongful convictions on public opinion. J. Exp. Criminol. 2020, 16, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, L.K. Episodic frames, HIV/AIDS, and African American public opinion. Polit. Res. Q. 2010, 63, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, S.A.; Harwood, J. The influence of episodic and thematic frames on policy and group attitudes: Mediational analysis. Hum. Commun. Res. 2015, 41, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbett, R.E.; Ross, L. Human Inference: Strategies and Shortcomings of Social Judgment; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, R.L.; Taylor, S.E.; Wood, J.V.; Thompson, S.C. The vividness effect: Elusive or illusory? J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, P.K.; Cialdini, R.B. Fluency of consumption imagery and the backfire effects of imagery appeals. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigney, J.W.; Lutz, K.A. Effect of graphic analogies of concepts in chemistry on learning and attitudes. J. Educ. Psychol. 1976, 68, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Hondo, H. An integrated review of communication research focusing on information formats: Toward applications to energy and environmental problems. J. Jpn. Inst. Energy 2021, 100, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Change of Japan. Available online: https://www.data.jma.go.jp/cpdinfo/ccj/2020/pdf/cc2020_shousai.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- McDonald, R.I.; Chai, H.Y.; Newell, B.R. Personal experience and the “psychological distance” of climate change: An integrative review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 44, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocco, P.J.; Green, M.C.; Sasota, J.A.; Jones, N.W. This Story Is Not for Everyone: Transportability and Narrative Persuasion. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2010, 1, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Mawad, F.; Giménez, A.; Maiche, A. Influence of rational and intuitive thinking styles on food choice: Preliminary evidence from an eye-tracking study with yogurt labels. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 31, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravec, P.L.; Kim, A.; Dennis, A.R. Appealing to sense and sensibility: System 1 and System 2 interventions for fake news on social media. Inf. Syst. Res. 2020, 31, 987–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Goldman, R. Personal involvement as a determinant of argument-based persuasion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 41, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Schumann, D. Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: The moderating role of involvement. J. Consum. Res. 1983, 10, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Narrative | Episodic | Vivid | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Story | ✓ | ✓ | - |

| Characters | ✓ | ✓ | - |

| Specific and concrete cases | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Awakens emotion | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Highly imaginative expression | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Measure | Division | Total Number of Responses | Number of Valid Responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 1055 | 388 |

| Female | 1066 | 520 | |

| Age | 18–29 | 418 | 173 |

| 30–39 | 423 | 189 | |

| 40–49 | 426 | 182 | |

| 50–59 | 427 | 190 | |

| 60+ | 427 | 174 |

| Narrative (N = 459) | Logical (N = 449) | t-Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Transportability | 3.684 | 1.316 | 3.555 | 1.290 | t(906) = 1.496, p = 0.135 |

| Intuitiveness | 3.573 | 1.067 | 3.595 | 1.036 | t(906) = −0.310, p = 0.757 |

| Interest | 3.941 | 1.072 | 3.851 | 1.120 | t(906) = 1.241, p = 0.215 |

| Narrative (N = 459) | Logical (N = 449) | t-Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Comprehensibility | 4.209 | 0.594 | 4.105 | 0.615 | t(906) = 2.600, p = 0.010 |

| Anxiety | 4.181 | 0.858 | 3.982 | 1.027 | t(906) = 3.155, p = 0.002 |

| Fear | 4.089 | 0.926 | 3.815 | 1.092 | t(906) = 4.072, p < 0.001 |

| Urgency | 4.312 | 0.762 | 4.171 | 0.900 | t(906) = 2.525, p = 0.012 |

| Responsibility | 4.037 | 0.913 | 3.802 | 0.987 | t(906) = 3.722, p < 0.001 |

| Guilt | 3.606 | 1.029 | 3.314 | 1.110 | t(906) = 4.100, p < 0.001 |

| CO2 reduction | 4.181 | 0.845 | 3.918 | 0.972 | t(906) = 4.346, p < 0.001 |

| Information seeking | 3.495 | 1.032 | 3.321 | 1.014 | t(906) = 2.557, p = 0.011 |

| Participation in discussions | 2.956 | 1.133 | 2.804 | 1.081 | t(906) = 2.072, p = 0.039 |

| Carbon tax | 2.702 | 1.143 | 2.559 | 1.139 | t(906) = 1.879, p = 0.061 |

| Renewable energy tax | 2.725 | 1.208 | 2.530 | 1.162 | t(906) = 2.483, p = 0.013 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nakano, Y.; Hondo, H. Narrative or Logical? The Effects of Information Format on Pro-Environmental Behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021354

Nakano Y, Hondo H. Narrative or Logical? The Effects of Information Format on Pro-Environmental Behavior. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021354

Chicago/Turabian StyleNakano, Yuuki, and Hiroki Hondo. 2023. "Narrative or Logical? The Effects of Information Format on Pro-Environmental Behavior" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021354