The Mediating Role of Anxiety between Parenting Styles and Academic Performance among Primary School Students in the Context of Sustainable Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

Purpose of the Study and Working Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Parenting Styles

2.2.2. Cognitive Test Anxiety

2.2.3. Academic Performance

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Factorial Validity of the Cognitive Test Anxiety Scale-Short Form (CTAS-SF) on the Romanian Sample

3.2. Preliminary Analysis

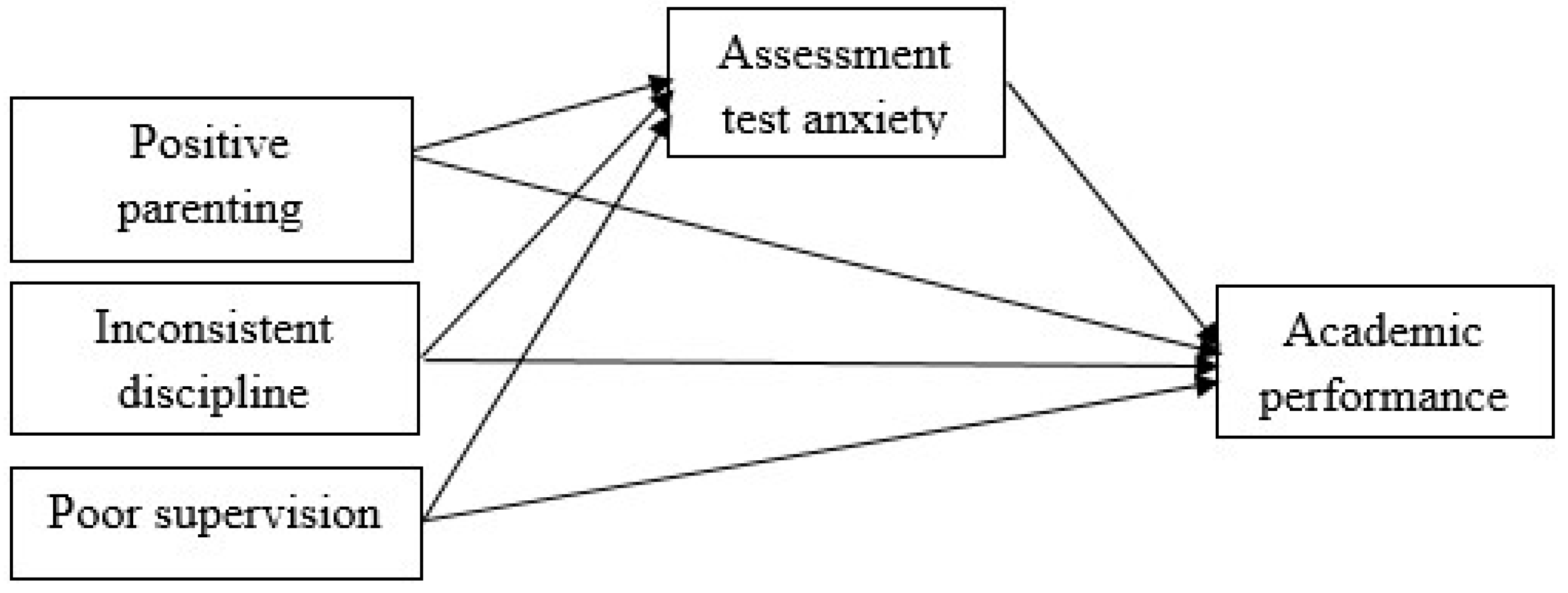

3.3. Mediation Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mennuti, R.B.; Christner, R.W.; Freeman, A. Intervenții Cognitiv-Comportamentale în Educație. In Ghid Practice; ASCR Publishing House: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, L.W.; Liebert, R.M. The effects of anxiety on timed and untimed intelligence tests. Another look. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1969, 33, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robu, V. Anxietatea Faţă de Evaluarea Orală în Rândul Liceenilor. In Idei şi Valori Perene în Ştiinţele Socio-Umane. Studii şi Cercetări; Gugiuman, A., Ed.; Argonaut Publishing House: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2008; Volume 1, pp. 299–321. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez-Peñaa, M.I.; Suárez-Pellicionic, M.; Bonoa, R. Gender differences in test anxiety and their impact on higher education students’ academic achievement. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 228, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntley, C.D.; Young, B.; Smith, C.T.; Peter, L. Uncertainty and test anxiety: Psychometric properties of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale—12 (IUS-12) among university students. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 104, 101672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, K.; Lawford, H.; Hood, S.; Oliveira, V.; Murray, M.; Trempe, M.; Crooks, J.; Jensen, M. Student Anxiety and Evaluation. Collect. Essays Learn. Teach. 2019, 12, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racu, I.; Lungu, V. Assessment of metacognitive beliefs about concern. Soc. Work. Educ. 2019, 56, 52–60, ISSN 1857–0224. [Google Scholar]

- Otomega, I.M.; Şleahtiţchi, M. Differentiation of Genes is the Phenomenon of Anxious Social Adolescents. In Preocupări Contemporane ale Ştiinţelor Socio-Umane, 6th ed.; Rusnac, V., Ed.; Universitatea Liberă Internaţională in Moldova: Chișinău, Moldova, 2015; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Baig, W.A.; Al-Zahrani, E.M.; Al-Jubran, K.M.; Chaudhry, T.; Qadri, A.A. Evaluation of Test Anxiety Levels among Preparatory Year Students of PSMCHS During Computer-Based Versus Paper-and-Pen Examination. Int. J. Med. Health Res. 2018, 7, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Ajmal, A. Fear of Negative Evaluation and Social Anxiety in Young Adults. J. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2019, 4, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkayish, A. Psychological Aspects of Examination Anxiety and Ways to Cope with it. Azərbaycan Məktəbi 2018, 683, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sójka, A.; Stelcer, B.; Roy, M.; Mojs, E.; Pryliński, M. Is there a relationship between psychological factors and TMD? Brain Behav. 2019, 9, e01360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, F.; Mammarella, I.C.; Devine, A.; Caviola, S.; Passolunghi, M.; Szűcs, D. Maths anxiety in primary and secondary school students: Gender differences, developmental changes and anxiety specificity. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2015, 48, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringeisen, T.; Raufelder, D. The interplay of parental support, parental pressure and test anxiety e Gender differences in adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2015, 45, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnell, K.; Ringeisen, T.; Raufelder, D.; Rohrmann, S. The impact of adolescents’ self-efficacy and self-regulated goal attainment processes on school performance—Do gender and test anxiety matter? Learn. Individ. Differ. 2015, 38, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesghina, A.; Richland, L.E. Impacts of Expressive Writing on Children’s Anxiety and Mathematics, Learning: Developmental and Gender Variability. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 63, 101926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putwain, D.W.; Stockinger, K.; von der Embse, N.P.; Suldo, S.M.; Daumiller, M. Test anxiety, anxiety disorders, and school-related wellbeing: Manifestations of the same or different constructs? J. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 88, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, P.J.; Robinson, C.M. Development and Evaluation of the Anxiety Disorder Diagnostic Questionnaire. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2010, 39, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeidner, M. Test Anxiety: The State of the Art; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Von der Embse, N.; Jester, D.; Roy, D.; Post, J. Test anxiety effects, predictors, and correlates: A 30-year meta-analytic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 277, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eysenck, M.W.; Payne, S. Effects of Anxiety on Performance Effectiveness and Processing Efficiency; Royal Holloway University of London: Egham, UK, 2006; Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Robu, V. Psihologia Anxietății Față de Testare și Examene; Performantica Publishing House: Iaşi, Romania, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Crişan, C.; Copaci, I. The Relationship between Primary School Childrens’ Test Anxiety and Academic Performance. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 180, 1584–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crișan, C.; Albulescu, I.; Copaci, I. The Relationship Between Test Anxiety and Perceived Teaching Style. Implications and Consequences on Performance Self- Evaluation. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 142, 668–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuderth, S.; Jabs, B.; Schmidtke, A. Strategies for reducing test anxiety and optimizing exam preparation in German university students: A prevention oriented pilot project of the University of Wurzburg. J. Neural. Transm. 2009, 116, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depreeuw, E.; De-Neve, H. Test Anxiety can Harm your Health: Some Conclusions based on a Student Typology. In Anxiety: Recent Developments in Cognitive, Psychophysiological, and Health Research, 1st ed.; Forgays, D.G., Sosnowski, T., Wrzesniewski, K., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 211–228. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, S.; Egooler, L.; Scriven, M. Strategies for Managing Evaluation Anxiety: Toward a Psychology of Program Evaluation. Am. J. Eval. 2002, 23, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, A.M.; Maloney, E.A.; Fugelsang, J.; Riskoa, E.F. On the relation between math and spatial ability: The case of math anxiety. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2015, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, K.; Ginsburg, G. Family factors in the development, treatment, and prevention of childhood anxiety disorders. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 15, 144–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cargneluttia, E.; Tomasettob, C.; Chiara-Passolunghi, M. How is anxiety related to math performance in young students? A longitudinal study of Grade 2 to Grade 3 children. Cogn. Emot. 2016, 31, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nealy, C.E.; O’Hare, L.; Powers, J.D.; Swick, D.C. The Impact of Autism Spectrum Disorders on the Family: A Qualitative Study of Mothers’ Perspectives. J. Fam. Soc. Work 2012, 15, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradian, J.; Alipour, S.; Shehni Yailagh, M. The causal relationship between parenting styles and academic performance mediated by the role of academic self-efficacy and achievement motivation in the students. J. Fam. Psychol. 2021, 1, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Masud, H.; Ahmad, M.S.; Jan, F.A.; Jamil, A. Relationship between parenting styles and academic performance of adolescents: Mediating role of self-efficacy. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2016, 17, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Dorso, E.; Renk, K. The Relationship among Parenting Styles Experienced during Childhood, Anxiety, Motivation, and Academic Success in College Students. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. (CSR) 2016, 9, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawe, E.; Lightfoot, U.; Dixon, H. Firstyear students working with exemplars: Promoting self-efficacy, self-monitoring and self- regulation. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2017, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, D.; Chan, K.K.H. Managing dialogic use of exemplars. Assessment & Evaluation. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, C.; Price, M.; Donovan, B. Improving students’ learning by developing their understanding of assessment criteria and processes. Assess Eval. High Educ. 2003, 28, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, M.; Qasmieh, N.; Racz, S.J.; Weeks, J.W.; De LosReyes, A. The Fears of Evaluation About Performance (FEAP) Task: Inducing Anxiety-Related Responses to Direct Exposure to Negative and Positive Evaluations. Behav. Ther. 2020, 51, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robu, V. Test anxiety in adolescents: A data set obtained in a sample of high school students. Psychol. Sci. Pract. J. 2014, 3, 81–98, Online-ISSN: 2537–6276. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, J.P. Improves Performance and Reduces Evaluation Anxiety in Classroom Exam Situations. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2016, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.J.; Rapee, R.M.; Bayer, J.K. Prevention and early intervention of anxiety problems in young children: A pilot evaluation of Cool Little Kids Online. Internet Interv. 2016, 4, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robu, V. Anxietatea Faţă de Testare: Diferenţe de Gen. In Cercetarea Psihologică Modernă: Direcţii şi Perspective; Milcu, M., Griebel, W., Sassu, R., Eds.; Universitară Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2008; pp. 116–131. [Google Scholar]

- Tochahi, E.S.; Sangani, H.R. The Impact of Interactionist Mediation Phase of Dynamic Assessment as a Testing Tool to Deviate Anxious Learners towards Facilitative Anxiety. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 192, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, M.W.; Derakshan, N.; Santos, R.; Calvo, G.M. Anxiety and Cognitive Performance. Atten. Control Theory 2007, 7, 336–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righi, S.; Mecacci, L.; Viggiano, M.P. Anxiety, cognitive self-evaluation and performance: ERP correlates. J. Anxiety Disord. 2009, 23, 1132–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, A.L.; Kirtley, M.S. Gender Differences in the Relationships Among Parenting Styles and College Student Mental Health. J. Am. Coll. Health 2012, 60, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Atram, A.A. The Relationship between Parental Approach and Anxiety. Arch Depress. Anxiety 2015, 1, 006–009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgar, F.J.; Waschbusch, D.A.; Dadds, M.R.; Sigvaldason, N. Development and validation of a short form of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2007, 16, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florean, I.S.; Dobrean, A.; Balazsi, R.; Roșan, A.; Păsărelu, C.R.; Predescu, E.; Rad, F. Measurement invariance of Alabama parenting questionnaire across age, gender, clinical status, and informant. Assessment 2022, 2022, 10731911211068178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassady, J.C.; Finch, W.H. Confirming the factor structure of the Cognitive Test Anxiety Scale: Comparing the utility of three solutions. Educ. Assess. 2014, 19, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassady, J.C.; Johnson, R.E. Cognitive test anxiety and academic performance. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 27, 270–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfradt, U.; Hempel, S.; Miles, J.N. Perceived parenting styles, depersonalisation, anxiety and coping behaviour in adolescents. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2003, 34, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. RLP | 83.54 | 15.13 | - | |||||

| 2. MP | 86.85 | 13.91 | 0.469 *** | - | ||||

| 3. CTA | 1.97 | 0.60 | −0.241 *** | −0.389 *** | 0.886 | |||

| 4. PP | 4.61 | 0.50 | 0.111 | 0.103 | −0.093 | 0.619 | ||

| 5. ID | 2.66 | 0.83 | −0.008 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.035 | 0.526 | |

| 6. PS | 2.00 | 1.15 | −0.260 *** | −0.297 *** | 0.139 * | −0.173 ** | 0.127 | 0.656 |

| Predictor | Mediator | Dependent Variable | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | CTA | RLP | 0.901 | 0.219 (−0.099, 0.611) |

| ID | CTA | RLP | −0.040 | −0.009 (−0.222, 0.221) |

| PS | CTA | RLP | −1.136 * | −0.127 (−0.309, −0.008) |

| PP | CTA | MP | 0.626 | 0.332 (−0.149, 0.831) |

| ID | CTA | MP | 0.058 | −0.013 (−0.318, 0.293) |

| PS | CTA | MP | −0.995 * | −0.199 (−0.416, −0.011) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Albulescu, I.; Labar, A.-V.; Manea, A.D.; Stan, C. The Mediating Role of Anxiety between Parenting Styles and Academic Performance among Primary School Students in the Context of Sustainable Education. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1539. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021539

Albulescu I, Labar A-V, Manea AD, Stan C. The Mediating Role of Anxiety between Parenting Styles and Academic Performance among Primary School Students in the Context of Sustainable Education. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):1539. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021539

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbulescu, Ion, Adrian-Vicențiu Labar, Adriana Denisa Manea, and Cristian Stan. 2023. "The Mediating Role of Anxiety between Parenting Styles and Academic Performance among Primary School Students in the Context of Sustainable Education" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 1539. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021539

APA StyleAlbulescu, I., Labar, A.-V., Manea, A. D., & Stan, C. (2023). The Mediating Role of Anxiety between Parenting Styles and Academic Performance among Primary School Students in the Context of Sustainable Education. Sustainability, 15(2), 1539. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021539