Abstract

The sustainable competitiveness of an organization is largely dependent upon its effectiveness in developing and maintaining high levels of socializees’ work engagement. Based on COR (conservation of resources) theory, the present study proposes an integrative model of work engagement pathway to organizational socialization. LMX (leader–member exchange) is seen to create fertile or infertile ground for the creation or limitation of six adjustment-specific resources (e.g., task mastery), which in turn affect work engagement. SmartPLS 3.0 is employed to analyze the data with 455 respondents from 15 luxury hotels on China’s Hainan Island. As a result, the six adjustment-specific resources collectively and fully mediate the LMX–engagement relation. LMX positively influences all six adjustment-specific resources, which then either directly or conditionally affect work engagement. While engagement’s relationship with task mastery is moderated by income, its relationship with fitting in is moderated by line vs. staff department. The foregoing findings are exploratory and insightful, particularly considering that the work engagement pathway to organizational socialization has become a new paradigm with important implications for theory, research, and practice.

1. Introduction

Globally, work engagement is increasingly recognized as the key to organizational competitive advantages and business profits in general [1], and in hospitality and tourism organizations, in particular (e.g., [2,3]). Hotel organizations, for example, are people-based, labor-intensive, and service-oriented, and therefore, their business success is largely dependent upon their engaged employees (e.g., [4]). This would suggest that developing high levels of socializees’ work engagement is an effective leadership approach to achieving success-related socialization outcomes [2,5,6,7,8] (Socializees denote employees who are being socialized into their employment organization; they could be newcomers, recent newcomers, and/or veterans whenever assimilation or reassimilation are necessary [5,9]).

Despite its importance, the levels of work engagement are continuously reported in industry surveys to decline among workers worldwide [1]. Only 24% of the employees in Southeast Asian countries, for instance, are engaged at work [10]. In this respect, research over the past decade reveals that work engagement fluctuates both within persons and across time and situations [7]. In the context of organizational socialization, the development and maintenance of socializees’ work engagement is a critical and difficult task [7,11]. The level of socializees’ work engagement is, as per Saks and Gruman [7], often seen to decline soon after their entry into the organization, and this decline is referred to as a hangover effect. Following their entry into the organization, socializees are likely to experience such negative “hangover effects”, unless socialization practices are effectively designed and implemented to proactively cope with these problems [7,8].

Organizational socialization refers to the process whereby socializees transform themselves from rank outsiders to effective and engaged insiders [7]. Socializees assimilate into their organization quickly, and their early adjustment experiences have short- and long-term effects on subsequent organizational outcomes (e.g., organizational cultural inheritance) and personal outcomes (e.g., sustainable career development) (e.g., [7]). Neglecting to socialize newcomers, as per [12], has been proven to have negative consequences such as psychological need dissatisfaction and/or withdrawal cognitions. Although leadership has been argued to influence socializees’ work engagement, such questions as how, why [7], and under what conditions [13] this influence occurs remain answered in an incomplete manner for two main reasons. One is that work engagement has received very little attention in the socialization research domain, albeit it has become an important topic in management. The other is that socialization research has been dominated by uncertainty reduction theory (URT, [14]), an almost exclusive pathway to organizational socialization (e.g., [7]). URT assumes that the socialization process is somewhat negative such that socializees often experience uncertainty and anxiety [7]. URT also suggests that factors both in the organization (e.g., socialization tactics) and in the person (e.g., information seeking) help socializees minimize or reduce job demands (e.g., role ambiguity and role conflict), which in turn affect work engagement [14]. However, URT has its limitations when it comes to work engagement, such that job demands underscored in URT are less salient than job resources for predicting work engagement [7]. As such, Saks and Gruman [7] alternatively propose a socialization resource theory (SRT) approach to socializees’ work engagement.

Saks and Gruman [7] argue that in the process of organizational socialization, providing socializees with necessary socialization resources can effectively cope with the problem of socializees’ disengagement. They further define a resource as anything perceived by the individual to aid in the achievement of their goals. They continue to suggest that one major goal of socializees is to gain resources to develop and foster socializees’ work engagement. In particular, Saks and Gruman [7] argue that socialization resources (e.g., supervisor support) have both direct and indirect—through personal resources (e.g., self-efficacy)—effects on socializees’ work engagement. One merit of Saks and Gruman’s [7] model of SRT is that it offers an engagement pathway—an alternative approach—to studying organizational socialization. One notable limitation of this model, however, concerns its neglect of potential moderation variables such as income, organizational culture/subculture [15], and proactive personality [13], among others. One more notable limitation of this SRT model involves its exclusion of some critical resource constructs (e.g., resource caravans and caravan passageways), although individual resources such as self-efficacy, fit perceptions, and supervisor support are theorized. While a resource caravan refers to the cluster of resources that travel together in unique ways for employees and organizations, a caravan passageway denotes factors in the leadership and/or the organization that fosters employees’ resources or depletes their resource reservoirs [16]. Therefore, it could be understood that the caravan passageway is the key to both providing sustainable organizational socialization resources and dealing with the problems associated with socializees’ disengagement.

Through the lens of COR (conservation of resources) theory [16,17], LMX (leader-member exchange, [18]) could be conceived as a kind of caravan passageway (LMX denotes the working relationship between followers and their leaders. Followers, for example, develop exchange relationships with their leader based on mutual trust, respect, and obligation [18]; the quality of exchange, in turn, affects their attitudes and behaviors at the workplace [19]). In a given situation, LMX may present itself, as per Sarandopoulos and Bordia [20], as a resource passageway (i.e., high-quality LMX relationship or “in−group”) or barren passageway (i.e., low-quality LMX or “out-group”). This is because leaders are seen to form differential relationships with their members, ranging from lower to higher quality exchanges [21]. Wang et al. [22] document that LMX influences organizational citizenship behavior through organizational justice as perceived by hotel front-line employees. An argument could be extended to expect, as per Hobfoll et al. [17], that LMX may foster or deplete employees’ resource pools, which in turn affect their work engagement.

From the perspective of COR theory [17], socializee adjustment could be conceived as a cluster of socialization-specific resources, namely, a resource caravan [7]. Song et al. [23] define an adjustment-specific resource caravan as what is actually obtained, gained, adapted, learned, and changed following socializees’ entry into the organization (In the literature, adjustment-specific resources are alternatively labeled as assimilation-specific adjustment outcomes, proximal socialization outcomes, and newcomer/recent newcomer adjustment outcomes, among others). In particular, an adjustment resource caravan involves task mastery, fitting in, standing out, role negotiation, membership identification, and interpersonal relationships [23]. This caravan, as per Song et al. [23] and Hobfoll [16], involves resources from both role taking (e.g., fitting in) and role making (e.g., role negotiation). While the former resources are obtained through changing socializees themselves to assimilate into existing organizational roles and systems, the latter resources are developed through job crafting—changing job demands and resources—to meet employees’ personal needs and to play with their strengths [21]. Alternatively, the foregoing resource caravan includes, as per Hobfoll [16], structural resources (e.g., task mastery), sociocultural resources (e.g., fitting in), and psychosocial resources (e.g., membership identification), among others.

A meta-review of socialization literature [14] indicates that adjustment-specific factors are often treated as putative mediators in socialization models. In the literature, the majority of socialization works examine the mediating roles of either role taking (e.g., role clarity, self-efficacy, and social integration [14]) or role making (e.g., job crafting [21]), with only a few exceptions. Song and Chathoth [24], for instance, investigate the mediating roles of both role taking and role making dimensions of adjustment-specific resources in the relationship between core self-evaluations and job performance. To our knowledge, there has been, however, a lack of empirical evidence on the potential mediating roles of the foregoing six adjustment-specific resources in the relationship between LMX and socializees’ work engagement. Despite the positive influence of job resources on work engagement being well established, it generally remains unclear how and why and under what conditions different types of job resources affect work engagement differentially [15,25].

Based on COR theory [16,17], we, therefore, proposed an integrative model of socializees’ work engagement, whereby the impact of LMX on socializees’ work engagement is transmitted by the foregoing six adjustment-specific resources. In addition, some of the foregoing direct paths might be moderated by socializees’ income and affiliated departments. Specifically, we approached our analysis with the following four research questions in mind:

- (1)

- Does LMX have a direct influence on each of the six foregoing adjustment-specific resources?

- (2)

- How many of the foregoing six resources, in turn, could significantly predict socializees’ work engagement?

- (3)

- Will the relationship between LMX and work engagement be mediated by the foregoing six adjustment-specific resources? and

- (4)

- Will socializees’ income and affiliated department moderate the relationships between adjustment-specific resources and work engagement?

In exploring answers to the foregoing research questions, we are most likely to contribute to the literature in several ways. First, this study advances organizational socialization research significantly by exploring mechanisms of adjustment-specific resources underlying the relationship between LMX and work engagement. In particular, the overall and specific mediating roles of the six adjustment-specific resources will be revealed in the present study, and they will explain how, why, and under what boundary conditions LMX influences socializees’ work engagement. Second, previous theories (e.g., SRT; Ref. [7]) and empirical works [13] have a focus on socialization resources (e.g., mentoring, support, and self-efficacy) at the individual level; the present study underscores socialization resources at the cluster level because COR theory [17] argues that resources exist and travel in caravans for both employees and organizations. Specifically, high-quality LMX is regarded as a resource caravan with a cluster of leader-level resources, including the leader’s support, recognition, trust, and obligations, among others [17,18]. From the perspective of COR, LMX is seen to create fertile or infertile ground for the creation or limitation of an adjustment-specific resource caravan, which further leads to socializees’ work engagement/disengagement. These findings are exploratory and valuable, particularly considering that the work engagement pathway to organizational socialization has become a new research paradigm [7] with important implications for theory and practice. Last but not least, corporate sustainability theory [26], for instance, does not currently address the issues of work engagement. Therefore, study findings regarding the proximal and distal antecedents of socializees’ work engagement also have theoretical implications for the refinement of corporate sustainability theory and practice.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. The Research Framework and COR Theory

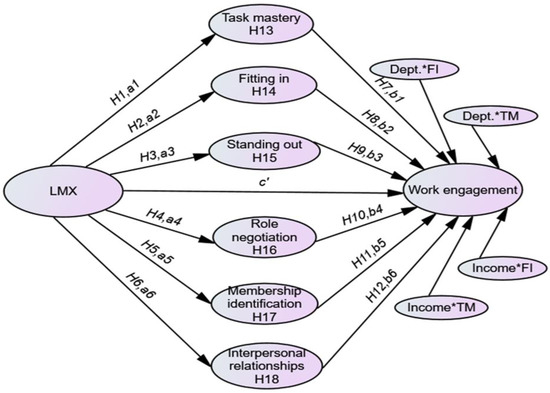

In our research framework (see Figure 1), LMX—a caravan passageway—is seen to create fertile or infertile ground for the creation or limitation of adjustment-specific resource caravan, which further leads to socializees’ work engagement/disengagement. This model is built on COR theory [16,17] for one notable reason. Namely, COR theory enables investigators to generate a large variety of specific hypotheses that are significantly more comprehensive than those provided by other theories that focus on a single primary resource [17]. In this particular study, COR enables us to explain how, why, and under what conditions LMX influences work engagement.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of this study. Note: 1. Path c concerns the direct effect of LMX on work engagement without controlling for the six putative mediators; after controlling for the mediators, path c is accordingly changed into path c’. 2. Hypothesis 13 concerns the six mediators collectively transmitting the effect of LMX to work engagement. 3. Control variables include age, gender, income, education, and department. 4. * indicates that Dept. and Income are moderators.

First, one basic premise of COR is that resource acquisition and conservation are imperative for socializees to adjust to the work, cope with job demands, and sustain work engagement [7]. While the holders of greater support resources (e.g., high-quality LMX) are more capable of coordinating resource gain and less susceptible to resource loss, employees with less supportive resources are more prone to resource loss and less able to acquire new resources [16]. On the basis of COR’s gain spiral corollary, high-quality LMX could be understood as the initial gain of a resource caravan (e.g., mutual trust, support, and recognition; Ref. [17]), which begets additional gains in terms of an adjustment-specific resource caravan, including higher levels of fitting in and standing out, among others.

Second, COR [17] suggests that job resources have motivational effects on work engagement. In this respect, the motivational effects of adjustment-specific caravan resources could be, as per Saks and Gruman [7], both extrinsic (e.g., instrumental in the development of engagement) and intrinsic (satisfying psychological needs of meaningfulness and relatedness, among others).

Third, apart from its dimension of gaining and conserving resources, COR has an additional dimension, namely, the crossover effect of resources and engagement through social exchanges [17]. For instance, the employees with high-quality LMX receive more leader-level resources than their counterparts with low-quality LMX [17]. COR theory [17] maintains that the social exchange of resources results in a crossover of work engagement from leaders to followers.

2.2. LMX and Adjustment-Specific Resources

According to Graen and Uhl-Bien [18], LMX theory highlights the dyadic relationship quality between followers and leaders. High-quality LMX, for example, provides employees with a conditional resource caravan (e.g., mutual trust and support). Resource holders could then take advantage of these conditional resources to further develop structural, psychosocial, and sociocultural resources [27]. As such, it could reasonably expect that the higher the quality of the LMX relationship, the better the task mastery should be. While task mastery involves the relationship between socializees and their jobs, fitting in concerns socializees’ adjustment to their organizational culture [24]. In particular, fitting in is reflective of a socializee’s internalization and recognition of their organization’s norms, values, and practices [23]. From the perspective of COR, LMX should be predictive of fitting in. One possible reason for this is that in-group socializees are more likely—than their counterparts of out-group socializees—to be invited to attend social activities. This provides in-group socializees with more opportunities to interact with insiders, resulting in a deeper cultural understanding of the employment organization. Therefore, high-quality LMX offers socializees a bundle of socialization resources that facilitate their fitting in.

Furthermore, corporate sustainability theory suggests that organizational sustainability could be achieved through the approach of leadership and management [26]. In particular, managers’ coaches, training, and interactive communications facilitate socializees’ endeavors in both task mastery and cultural fitting in at the new workplace. To our best knowledge, empirical evidence on the causalities between LMX and each of fitting in and task mastery has been lacking thus far in the socialization literature. Therefore, the present study develops the first and second research hypotheses as follows:

Hypothesis 1.

Higher level of LMX relates to higher level of task mastery.

Hypothesis 2.

Higher level of LMX relates to lower level of difficulty in fitting in.

While fitting in requires socializees to behave just like everybody else in the organization, standing out requires socializees to exhibit their competitive advantages over other colleagues [23]. Socializees’ competitive advantages are due, in part, to their high-quality LMX relationships that are often characterized by mutual support and recognition [18]. According to Saks and Gruman and Song et al. [7,23], supervisors tend to offer a variety of resources such as autonomy and challenging work assignments to help socializees stand out from the crowd. As a result, in-group socializees are more likely to gain competitive advantages over their counterparts of out-group colleagues.

According to Song et al. [23], role negotiation denotes socializees’ perceived level of difficulty in changing their work role rather than changing themselves for the sake of effective work adjustment. As noted earlier, high-quality LMX relationships often take the characteristics of mutual trust, tolerance, and openness, among others [18]. As a result, in-group socializees are more likely to have opportunities than their counterparts to discuss their creative ideas and individualized requirements with their supervisors [18]. Likewise, supervisors are more likely to value and adopt those constructive suggestions for work/role changes. Based on the foregoing, this study developed the following two hypotheses.

Hypothesis 3.

Higher level of LMX relates to lower level of difficulty in standing out.

Hypothesis 4.

Higher level of LMX relates to lower level of difficulty in role negotiation.

According to Song and Chathoth [24], membership identification refers to the affiliation, self-identification, and pride of socializees as members of their new organization. High-quality LMX relationships help promote and develop socializees’ senses of membership identification for one main reason—the higher the quality of LMX, the greater the employees are endowed with autonomy and empowerment [18]. This enables in-group socializees to work to their strengths such that they are allowed to decide what and how to do their work. As a result, socializees with high-quality LMX are very likely to feel that they are valuable and important members, thus increasing their self-enhancement and membership identification (e.g., [28]). In terms of interpersonal relationships, COR argues that leader-level resources (e.g., high-quality relationships) can be transferred to individual employees [17]. Based on the foregoing discussions, we develop the following two hypotheses.

Hypothesis 5.

LMX positively relates to membership identification.

Hypothesis 6.

LMX positively relates to interpersonal relationships.

2.3. Socializees’ Adjustment and Work Engagement

According to Rothbard [29], work engagement denotes “an attention devoted to and absorption in work” (p. 665). More broadly, Kahn [30] describes engagement as the manifestation of people’s selves in their work, in that their physical, cognitive, and emotional resources are fully invested in their work role and performance. The diversified engagement definitions, nevertheless, share somewhat similar components, including absorption (cognitive), dedication (emotional), and vigor (physical), among others [6].

Previous studies (e.g., [31]) reveal that employees exhibit a higher level of work engagement when a variety of resources are available for them at the workplace. COR theory [17] suggests that job resources have motivational effects on work engagement. We, therefore, expect that the six adjustment-specific resources predict work engagement. This is because task mastery and fitting in enable socializees to satisfy their psychological needs for relatedness, competence, safety, and availability in their new job/task and organizational culture. This is also because the foregoing two resources are instrumental in developing engagement [7]. In short, task mastery and fitting in have, as per Hobfoll et al. [17], both intrinsic and extrinsic motivational effects on work engagement, leading to the seventh and eighth hypotheses.

Hypothesis 7.

The better task mastery, the higher the level of work engagement.

Hypothesis 8.

The less socializees report their difficulty in fitting in, the more they exhibit a higher level of work engagement.

Second, standing out could be related to work engagement for one notable reason, namely, outstanding socializees are usually seen to have competitive advantages (e.g., more professional, skillful, and influential) over others [24]. They tend to set and realize challenging work goals, and doing so is likely to create a sense of achievement, meaningfulness, competence, and safety in the workplace [30]. Theoretically, such kind of sense is argued by Albrecht et al. [6] to be an important motivator for developing and maintaining work engagement. In the literature, Song and Chathoth [24] document that standing out is predictive of socializees’ job performance; an argument could then be extended to expect that standing out should have a positive influence on socializees’ work engagement.

According to Graen and Uhl-Bien [18], role negotiation enables employees to satisfy their needs for autonomy, empowerment, and achievement, among others. Once these needs have been met, socializees are very much likely to have felt psychological meaningfulness, availability, and safety. In the literature, while job crafting is documented to predict work engagement [21], role negotiation and standing out are reported to have direct influences on job performance [24]. Moreover, corporate sustainability theory [26] notes that effective value and vision communication between managers and associates motivates associates’ behavior of role making/innovation, which in turn leads to emotionally committed organizational members. Based on the foregoing discussions, arguments could be extended to expect that role negotiation and standing out have direct effects on socializees’ work engagement, leading to the following two hypotheses.

Hypothesis 9.

The less socializees report their difficulty in standing out, the more they exhibit a higher level of work engagement.

Hypothesis 10.

The less socializees report their difficulty in role negotiation, the more they exhibit a higher level of work engagement.

Finally, membership identification involves such kinds of positive emotions as the love and pride of being an effective organizational member [23]. Such kinds of feelings are emotional energy that inspires a sense of oneness with his/her organization. They also promote organizational members’ emotions of love and pride. Such positive emotional work experiences are manifestations of psychological meaningfulness, which is theorized by Kahn [30] as having a motivational effect on work engagement. Moreover, Interpersonal relationships should have motivational effects on work engagement because they meet socializees’ psychological needs of relatedness, safety, and availability. Despite the foregoing reasonable logic, there has been no empirical evidence on these causal paths; we, therefore, developed the following two research hypotheses:

Hypothesis 11.

Socializees’ membership identification positively relates to their work engagement.

Hypothesis 12.

Socializees’ interpersonal relationships positively relate to their work engagement.

2.4. Mediation and Moderation Effects in the Integrative Model

According to the crossover model of COR [17], high-quality LMX enables leader-level resources to be transferred to employee-level resources, which in turn help develop work engagement. In this indirect crossover, particular mediating and/or moderating mechanisms intervene in the foregoing transmission [17]. In the present study, the mediating mechanism involves adjustment-specific resources, and moderating mechanisms concern organizational culture/subculture and personal income. In terms of mediation, ref. [32] strongly argue that a multiple mediation model has many advantages over its counterpart of a simple mediation. Furthermore, Preacher and Hayes [32] raise an issue of total versus specific mediation, suggesting that both total and specific mediation should be examined.

In socialization literature, the work contributed by Song and Chathoth [24] is one of the few studies that address the foregoing mediation issues. In particular, they document that the effect of socializees’ core self-evaluations on their job performance is transmitted both totally by the six adjustment-specific mediators and specifically by parts of these mediators. In this vein, an argument could be extended to expect that the adjustment-specific resources function as the mediating mechanisms between LMX and work engagement. This extension is particularly necessary because work engagement, as well as its proximal and distal antecedents and consequences, are becoming, as per existing works (e.g., [7]), new and alternative pathways to organizational socialization. To our best knowledge, there has been a lack of empirical evidence on the aforementioned extension thus far. We, therefore, expect that the six adjustment-specific resources collectively and totally mediate the LMX–engagement relation, leading to a thirteenth hypothesis.

Hypothesis 13.

The effect of LMX on work engagement is collectively and totally transmitted by the six adjustment-specific resources.

With regard to specific mediations, COR theory [17] and its crossover model suggest that leader-level condition resources are transferred, through LMX, to employee-level job resources that have positive effects on work engagement (noted earlier). Based on this COR thesis, we postulate that the effects of LMX on work engagement are specifically mediated by the foregoing six adjustment-specific resources. These specific mediations are also jointly suggested by the foregoing direct hypotheses. Specifically, LMX is hypothesized to have direct influences on each of the six adjustment-specific factors (purported in H1 to H6), which in turn affect work engagement respectively (purported in H7 and H12). For instance, LMX has been hypothesized to have a direct effect on membership identification (H5), which in turn promotes work engagement (H11). Taken together, membership identification, therefore, specifically mediates the relationship between LMX and work engagement (H18). As such, the following six specific mediation hypotheses are developed.

Hypotheses 14.

The relationship between LMX and work engagement is specifically mediated by task mastery.

Hypotheses 15.

The relationship between LMX and work engagement is specifically mediated by fitting in.

Hypotheses 16.

The relationship between LMX and work engagement is specifically mediated by standing out.

Hypotheses 17.

The relationship between LMX and work engagement is specifically mediated by role negotiation.

Hypotheses 18.

The relationship between LMX and work engagement is specifically mediated by membership identification.

Hypotheses 19.

The relationship between LMX and work engagement is specifically mediated by interpersonal relationships.

In socialization literature, the six adjustment-specific factors have all been consistently predicted by core self-evaluations [24] and socialization tactics [23]. However, job performance has been significantly predicted only by task mastery, fitting in, and standing out [24]. In engagement literature, Zahari et al.’s [15] review findings indicate that some job resources (e.g., incentive and recognition) do not significantly relate to work engagement. Jointly, these results would suggest socializees’ work engagement is likely to be only predicted by some of the foregoing six adjustment-specific resources. A given potential insignificant direct causal path might be attributable to potential moderators. While Hofstede [33] notes that an administrative subculture differs from that of a customer interface, employees’ income is a well-known “hygiene” factor in management literature. As such, we would explore potential moderating roles of income and affiliated departments in our model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Measurement Scales

As shown in Appendix A, all theoretical constructs involved in this are operationalized using multi-item reflective scales. Unless otherwise specified, theoretical constructs were captured by 5-point Likert scales ranging from “1” (strongly disagree) to “5” (strongly agree). In particular, Song et al. [23] developed and validated the six adjustment factors, among which fitting in, standing out, and role negotiation were measured by a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “1” (extreme difficulty) to “5” (no difficulty). Work engagement was measured on a 7-point Likert scale (from “1” strongly disagree to “7” strongly agree), and it was developed by Rothbard [29] and validated by Song et al. [8] in their sample of hotel socializees.

Appendix A also presents the measurement scale of LMX adopted in this study. We pilot-tested the original LMX scale developed by Graen and Uhl-Bien [18] among 30 respondents. However, the reliability value of this version of the LMX scale was 0.57, lower than the threshold level of 0.70, because Chinese respondents had difficulty responding to the original questionnaire developed by a Western scholar. We then changed the questions in the original scale into corresponding statements, followed by measuring the extent to which they agree or disagree with each of the seven statements on a 5-point Likert scale. The composite reliability of the adapted scale of LMX in our 455 data set increased to 0.905.

In the literature, many scholars (e.g., [19]) measure the LMX quality as perceived only by followers. In his empirical data, Minsky [34] measure the same LMX scale [18] from both a supervisor and their subordinate, finding that there is a perception gap/difference between them. He further reports that communication is one of the key factors that significantly explain the variance of the foregoing perception gap/difference. In addition, the present study focuses on followers’ perceptions as well as their impact on corresponding attitudes and behavior at the workplace. As such, measuring LMX quality from the subordinate side is a reasonable strategy to realize our research objectives.

3.2. Data Collection and Participants

In the main study, 500 copies of questionnaires were administered between 2018 and 2019 to 15 luxury hotels/resorts (i.e., 4- to 5-star hotels) located in six major cities (i.e., Haikou, Sanya, Linshui, Wanning, Qionghai, and Wenchang) of Hainan Island, China (According to the annual statistical report from Hainan Tourism Administration Bureau, on average, in 2018 and 2019, there were 64 luxury hotels/resorts (4- to 5-star hotels) in Hainan Province, PR China). The moderately priced (3-star) and economy (1- to 2-star) hotels were not targeted organizations for one notable reason. Namely, socialization experiences in luxury hotels are usually more structured than those in moderately priced or economy hotels [8]. Moreover, the majority of luxury hotels/resorts on Hainan Island were located in the foregoing major cities. The targeted luxury hotels were selected by the snowball sampling technique based on personal relationships with and referrals from one hotel manager to another. One of the co-authors was an industry manager, and his helpers (i.e., the foregoing hotel managers) sent out hard copies of the questionnaires to newcomers and/or recent newcomers using a purposive sampling technique. Upon completion, the finalized questionnaires were sent back. Eventually, 476 copies (95.20% of the total) were returned. After our data screening/clearing, 455 copies were usable.

Before filling out the questionnaire, each respondent was asked to make sure that their organizational tenure was between 1 month and 24 months for several reasons. First, there has been a precedent (e.g., [23,35]) for socializees’ samples whose tenures fall within this time frame. Second, in the literature, there has been no agreement on the time frame of a socializee (e.g., [9]), which falls, nevertheless, within 1 to 36 months following their organizational entry (e.g., [23]). Third, existing works (e.g., [7,13]) generally agree that organizational socialization, in general, and newcomers and/or recent newcomers’ work engagement, in particular, differ from their tenured employee counterparts. Third, Jokisaari and Nurmi [35] argue that supervisor support should be continuous into the second year of employment. All things considered, our targeted population is therefore targeted to newcomers and recent newcomers (Levene’s test for homogeneity of variance of work engagement, for example, between newcomers and recent newcomers, was not statistically significant: F (453) = 2.294, p > 0.05).

3.3. Common Method Variance/Bias

In the present study, SmartPLS 3.0 was mainly used for hypothesis testing in addition to assessing constructs’ reliability and validity. Meanwhile, SPSS 23.0 and AMOs 23.0 were also used wherever necessary. Because our data is self-reported and cross-sectional in nature, we conducted two post-hoc tests for CMV/CMB (common method variance/bias) by taking the approaches of Harman’s [36] one-factor and Richardson et al.’s [37] ULMC (unmeasured latent method construct). In the former approach, all manifested items for the eight theoretical constructs were entered into a principal-component factor analysis with varimax rotation enabled in SPSS 23.0. As a result, the factor structure did not present itself as a single common factor, but multiple factors, among which the first factor explained 15.36% of the variance, smaller than the threshold level of 50%, as suggested by Harman [36]. This would suggest that CMV/CMB is not substantial in the present data.

In the latter approach, we developed four different measurement models of structural equation modeling enabled in AMOs 23.0, including (a) the trait model, (b) the method model, (c) the model of trait and method, and (d) the model of revised trait and method. First, model a (χ2/df = 2.51) fit the data significantly better (Δχ2 [21] = 4129.54, p = 0.000) than model b (χ2/df = 11.9). Second, model c (χ2/df = 2.138) fit the data better than model a (χ2/df = 2.51). Last, model d (χ2/df = 2.36) did not fit the data significantly worse (Δχ2 [13] = 114.7, p = 2.23) than model c (χ2/df = 2.14). Again, the foregoing comparative findings would collectively suggest, as per Richardson et al. [37], that CMV/CMB is not substantial in our empirical data.

4. Results

4.1. Respondents’ Characteristics

Approximately 46.8% of the 455 respondents were female and 53.2% of them were male. In terms of income, 218 respondents (47.9% of the total) reported that their monthly income was between RMB 2000 and 4000 (i.e., approximately between USD 158.42 and 633.03); A total of 107 respondents (23.5% of the total) reported that their monthly income was between RMB 4000 and 6000 (i.e., approximately between USD 158.42 and 633.03). In terms of educational level, a total of 188 respondents (41.3% of the total) had a 3-year college education or higher qualification, while 267 respondents (58.7% of the total) had senior high school education or below. Respondents’ organizational tenure all ranged from 1 to 24 months, of which 55.4% (252 of the total) varied from 1 to 12 months, and 44.6% (203 of the total) fell into the range of over 12 months to 24 months. More than half of the respondents (255 respondents, 56% of the total) were between the age of 20 and 29, followed by 172 respondents between 30 and 49 (37.8%) and 28 respondents (6.2% of the total) below 20.

4.2. Assessment Results of the Overall Measurement Model

Table 1 summarizes constructs’ means, standard deviations, loadings, and reliability, among others. The mean values for LMX and work engagement are 4.07 and 5.06, respectively. The mean values of adjustment-specific factors range from 3.70 (standing out) to 4.20 (membership identification). The skew values range from −0.841 to 0.505 (all smaller than 1), and Kurtosis values change from −0.199 to 1.002 (all smaller than 3). This would suggest, as per [38], that normality is not a substantial issue in the present data set, albeit it is not perfectly normally distributed. The VIF values ranged from 1.12 to 2.44, all smaller than 5, within the threshold level suggested by Hair et al. [38].

Table 1.

Assessment results of the overall measurement model.

In Table 1, the eight theoretical constructs present themselves to be reliable and valid. All composite reliability values were greater than 0.70, ranging from 0.910 to 0.949; likewise, all Cronbach’s alpha values varied from 0.869 to 0.928. The AVE values of the constructs were all greater than 0.50. Square root values of AVE (Table 2) varied from 0.799 to 0.922, all greater than their corresponding correlation values, as shown below the diagonal in Table 2. Furthermore, HTMT values (Table 3) ranged from 0.779 to 0.413, all smaller than 0.850, within the threshold level suggested by Henseler et al. [40]. Jointly, the foregoing results indicate, as per Hair et al. [38] and Henseler et al. [40], that all the latent constructs in the overall model exhibit acceptable levels of reliability and convergent, discriminant, and nomological validity. Finally, the overall model fits the data well because its SRMR value from SmartPLS 3.0 was 0.046, smaller than the threshold level of 0.080 suggested by Hair et al. [38].

Table 2.

Constructs’ correlations and discriminative validity.

Table 3.

HTMT discriminant validity of the constructs.

4.3. Hypothesis Testing Results

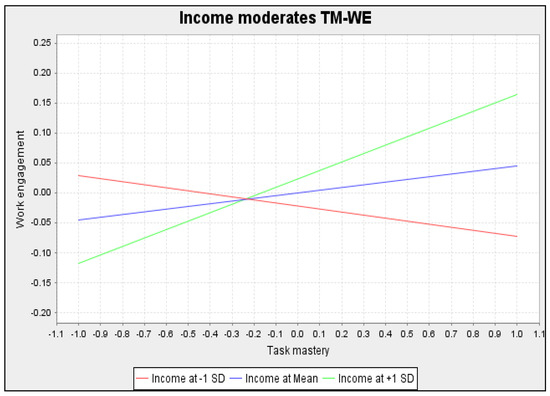

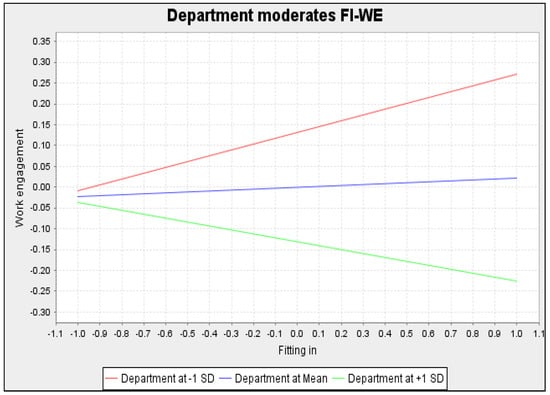

In the present study, all the hypotheses were tested using 455 parent samples with 7000 bootstraps in SmartPLS 3.0. First, Table 4 shows that all hypotheses on direct relationships (H1 to H12), except for H7 (TM→WE) and H8 (FI→WE), gained empirical support. Second, the two insignificant paths turned out to be due to their moderators. In particular, it reveals that: (a) income significantly moderates the effect of task mastery on engagement (β = 0.095, T = 2.156, Table 4, Figure 2) and (b) department moderates the influence of fitting in on engagement (β = −0.117, T = 2.28, Table 4, Figure 3). A post-hoc moderation test between two corresponding groups was performed. As a result, the effect of task mastery on work engagement was positively significant in the higher income group (monthly income > 4000 RMB, β = 0.159, T = 2.04), but not significant in the lower income group (monthly income ≤ 4000 RMB, β = 0.002, T = 0.018). While the effect of fitting in on work engagement is, as per Hair et al. (2017), negatively and marginally significant in the staff department group (β = −0.167, T = 1.704), the same path was otherwise positively and marginally significant in the line department group (β = 0.139, T = 1.857). Specifically, Hair et al. [38] argue that “in studies that are exploratory, a significance of 10% is commonly used” (p. 204). Last but not least, H13, regarding total mediation, also gained empirical support (β = 0.376, T = 7.896, Table 4). Moreover, all specific mediation hypotheses (H14 to H19), except for H14 and H15, gained empirical support in this study.

Table 4.

Summary of direct and indirect effects.

Figure 2.

Income moderates the relationship between task mastery and work engagement.

Figure 3.

Department moderates the relationship between fitting in and work engagement.

5. Discussion

5.1. Originalities and Theoretical Implications

5.1.1. Implications for Organizational Socialization Research

Our study is one of the small numbers of pioneer studies (e.g., [27]) whose research frameworks are built on COR theory. It significantly advances organizational socialization literature by using our hospitality sample as a pioneering empirical study on how, why, and under what conditions LMX affects socializees’ work engagement. Specifically, previous studies (e.g., [21]) report that LMX has both direct and indirect effects on work engagement. Specifically, the present data confirm the foregoing notion of direct effect (noted earlier) only in the absence of a proposed set of multiple mediators. In the presence of the foregoing mediators, the effect of LMX on work engagement, however, becomes insignificant; meanwhile, the total mediation effect of the six mediators is otherwise statistically significant. This shows that the whole set of the foregoing six resources collectively and fully mediate the LMX–engagement relation in the present sample. Comparatively, the LMX–engagement relation, for example, is only partially mediated by the whole set of four job crafting resources (e.g., structural job resources, social job resources) in Radstaak and Hennes’ [21] study sample.

With regard to specific mediation, our study results further reveal that LMX’s effect on work engagement is specifically mediated by all the foregoing six adjustment-specific resources except for task mastery and fitting in. In Radstaak and Hennes’ [21] sample, increasing structural job resources and decreasing hindering job demands are not significant specific mediators in the LMX–engagement relation, although increasing social job resources and challenging job demands are otherwise significant specific mediators in the same relation. Notably, there are two major differences between Radstaak and Hennes’ [21] study and the present study. While the former investigates tenured employees’ four job resources of role making, the latter investigates socializees’ six adjustment-specific resources through both role making and role taking. Theoretically, this implies that the LMX–engagement relation is more likely to be fully mediated when sufficient putative mediators are presented in multiple mediation models. In so doing, the possibility of parameter bias caused by omitted putative mediators in a given mediation model is decreased [32]. Taken together, the foregoing findings regarding total and specific mediation are exploratory and thus contribute significantly to the literature.

In terms of direct causal paths, it shows that LMX relates to all six adjustment-specific resources. In turn, four out of six resources are predictive of work engagement. Contrary to COR theory, task mastery and fitting in do not directly predict work engagement. In the literature, some job resources (e.g., recognition and incentive) are not empirically related to work engagement as well [15]. In the present study, income and department, nevertheless, have proven themselves as substantiated moderators. In particular, task mastery has a significant effect on work engagement only in the higher income group but not in the lower income group. This is reasonable because of the hygiene nature of income in motivational literature. Fitting in is positively related to work engagement in the hotel line department, but negatively in the hotel staff department. This echoes Hofstede’s [33] notion of subculture differences within an organization (noted earlier). To our knowledge, findings regarding moderation effects in this study are also original, and thus they significantly contribute to the socialization literature. These findings would theoretically imply that COR theory, in general, and SRT models of work engagement (e.g., [7]), in particular, may additionally theorize potential moderators as well as their effects on the direct links between some job resources and work engagement.

Previous theoretical models (e.g., [7]) and empirical works [13] in the socialization domain tend to underscore individual and separate socialization resources (e.g., supervisor support, mentoring, and self-efficacy). The present study extends socialization resources to collective and inter-related socialization resources. For example, high-quality LMX is considered a resource caravan with multiple leader-level resources, which is far more comprehensive than those individual socialization resources (e.g., supervisor recognition, feedback) in Saks and Gruman’s [7] engagement model of SRT. In addition, the six adjustment-specific resources in our model are far more comprehensive than individual adjustment-specific resources either in Saks and Gruman’s [7] theoretical model (i.e., fit perceptions, self-efficacy) or in Radstaak and Hennes’ [21] empirical framework (i.e., job crafting resources). As noted earlier, one major difference between the present study and Radstaak and Hennes’ [21] work concerns partial versus full mediation in the same relationship between LMX and work engagement.

Moreover, in response to the repeated call for an integrative model of organizational socialization [7], the present study incorporates the useful elements in URT and SRT approaches into our integrative model underpinned by COR theory. The integrative and comprehensive nature of resource caravans and passageways enable the present study to have merits. In particular, the overall and specific mediating roles of the six adjustment-specific resources have been unearthed in the present study, and they help understand how, why, and under what conditions LMX influences socializees’ work engagement. This would suggest, as per scholars (e.g., [7,24]), that the mediating mechanism of the resource caravan of socialization-specific adjustment makes a unique contribution to understanding organizational dynamics in the context of leadership as well as its influence on work engagement. This would also suggest that COR theory, in general, and its principles of caravan passageways, resource caravans, and crossover of resources, in particular, provide sound theoretical foundations for work engagement pathways to organizational socialization.

5.1.2. Implications for Corporate Sustainability Research

Our study findings provide implications for the model of sustainability organizational culture [41], organizational theory of resilience [42], and corporate sustainability theory [26]. According to Kantabutra et al. [42], corporate sustainability could be achieved through the approach of leadership and management. As a leadership method, LMX enables managers to assimilate socializees into organizational culture dimensions, including organizational goals, vision, value, rules, regulations, history, and common practice, among others [43]. The foregoing dimensions could be understood as role taking aspects of organizational culture [23]. In the present study, we provide empirical evidence on the direct influences of LMX on each of the role taking aspects, including cultural fitting in, task mastery, interpersonal relationships, and membership identification. In other words, LMX could be an effective approach to promote cultural inheritance, continuity, and stability in the process of organizational socialization. This lends support to corporate sustainability theory [26] in that sustainable organizations develop their own associates and managers for the sake of cultural continuity and stability [26,41].

In the present study, findings also reveal that LMX affects each of the role making dimensions, including role negotiation and standing out. They lend support for theoretical notions in the model of sustainability organizational culture [41], organizational theory of resilience [43], and corporate sustainability theory [26]. In particular, in sustainable organizations, leaders adopt the practices of perseverance, resilience development, and moderation to manage change, meet various challenges, and win new opportunities. In turn, these sustainable practices require organizational members to exhibit role making behaviors to continuously improve products, services, and processes for organizational stakeholders [41]. Based on the foregoing, it could be stated that keeping a balance between role making and role taking indicates that leadership and management are on the right track to managing and developing sustainable organizational culture.

Finally, our study findings reveal that each of role taking and role making dimensions in our sample either directly or conditionally leads to socializees’ work engagement. From the perspective of corporate sustainability theory, socializees’ behaviors of role taking and role making could be viewed as forms of developing and communicating sustainability visions and values, which are theoretically proposed to lead to emotionally committed organizational members [41]. As such, at least one more research proposition in sustainability organizational culture [41] could be extended to expect that role making and role taking (e.g., cultural fitting in and standing out) lead to engaged socializees in the workplace. This need is particularly felt considering that corporate sustainability theory [26], for instance, does not currently address the issue of work engagement. In this respect, COR theory underscores, however, the importance of work engagement and the crossover effect of engaged leaders on followers’ work engagement.

5.2. Practical Implications

While high-quality LMX could be a resource passageway with mutual recognition, trust, liking, and support, among other job resources, low-quality LMX could otherwise be a barren passageway with distrust, disliking, doubt, non-cooperation, and dissatisfaction, among other job demands [17,18]. This study shows that LMX—a resource passageway—promotes a cluster of socialization resources, which in turn either directly or conditionally affect socializees’ level of work engagement. This means that developing high-quality LMX is an important way to both proactively cope with the problems of socializees’ hangover effect and to achieve high levels of socializees’ work engagement. Therefore, a higher level of LMX, as perceived by hotel socializees, should be guaranteed and maximized as much as possible. For hotel managers, the effectiveness of their social exchange results with socializees is of paramount importance, given early socialization experiences have a quantifiable and long-lasting impact on socializees’ attitudes, behavior, and well-being [7]. From time to time, hotel managers may diagnose socializees’ LMX perceptions. In case their perceived LMX quality is low, an in-depth interview could be conducted to determine the barriers (e.g., leaders are too busy to have sufficient communication with their socializees) followed by corresponding management interventions, such as cultivating more frequent exchanges among leaders and followers to help socializees make good use of resource passageways and caravans of resources.

The caravan of adjustment-specific resources fully transmits LMX’s effect on work engagement. This shows that the six resources are interrelated, travel together, and jointly play the mediation role. This would suggest that hotel managers should encourage new and recent new hires to both take and make roles for the sake of effective adjustment. This would suggest that hotel managers should lay an emphasis on socializees’ role making, in addition to routine role taking. Hotel managers should audit socializees’ role making/taking index from time to time for the sake of developing and sustaining work engagement. In addition, hotel industry managers should foster their organizational subculture (e.g., administrative department’s subculture) to ensure positive engagement culture dominates. Meanwhile, increasing socializees’ incomes should also be an agenda of management objectives. In short, developing high-quality LMX presents itself to be an effective and useful resource passageway that promotes and fosters adjustment-specific resources, which in turn positively lead to socializees’ work engagement.

5.3. Limitations and Future Studies

Apart from the limitation of cross-sectional data (discussed earlier), one more limitation concerns snowball sampling and purposive sampling used in data collection. Although these sampling techniques are reasonably acceptable and our study is essentially exploratory, they make the generalizability of study findings unknown to a certain degree. However, the generalizability of our overall measurement model, for instance, has been suggested, as per DeVellis [44], due to factorial invariance (Δχ2 [28] = 30.28, p = 0.35) across the two split samples. It is therefore warranted that future studies with probability sampling should be conducted. Moreover, future studies should continue to use COR theory to guide empirical studies, exploring and confirming more antecedents of socializees’ work engagement. Other leader-level resources (e.g., servant leadership and spiritual leadership), other socializee-level job resources (e.g., PsyCap and role crafting), and job demands should be investigated for the sake of identifying more proximal and distal antecedents of work engagement. Furthermore, knowledge about the consequences of employees’ work engagement on organizational sustainability performance opens future directions for corporate sustainability research and practice. One generally agreed-upon indicator of organizational sustainability performance concerns the Triple Bottom Line, which argues that current sustainability issues can be resolved by achieving a balance between economic, social, and environmental prosperity (e.g., [42]).

6. Concluding Remarks

By drawing upon COR theory, we have proposed and tested an integrative model of socializees’ work engagement, whereby LMX, a caravan passageway, shapes adjustment-specific resources, which in turn either directly or conditionally affect work engagement. In addition, we have substantiated the total mediation effect as well as corresponding specific mediation effects in the LMX–engagement relation. Our findings are exploratory, novel, insightful, and therefore valuable for one notable reason. Namely, the mediating mechanism of the resource caravan of adjustment makes a unique contribution to understanding organizational dynamics. An interesting extension of our study findings could be conducting a comparative study in a Western context or other developing countries/regions. One more interesting extension concerns exploring more antecedents and potential consequences of socializees’ work engagement. A more probabilistic sampling method will enable our findings to be more generalizable. Finally, in terms of how, why, and under what conditions LMX affects work engagement, this study provides, nevertheless, both theoretical and practical contributions for other research investigators to build on.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L.; methodology, Z.S., H.L. and X.X.; software, Z.S. and X.X.; validation, J.L. and Z.S.; formal analysis, H.L., Z.S. and J.L.; investigation, Y.X.; resources, Y.X.; data curation, Y.X.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L., Z.S. and Y.X.; writing—review and editing, Z.S., X.X. and J.L.; visualization, J.L.; supervision, Z.S. and X.X.; project administration, Y.X. and Z.S.; funding acquisition, Z.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Fund of PR China under Grant 72262011.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request. However, the data are not publicly available because participants were informed that the data were confidential and that individual responses would never be known, as data analysis would be of all participants combined.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measurement scales of LMX, work engagement, and adjustment-specific scale.

Table A1.

Measurement scales of LMX, work engagement, and adjustment-specific scale.

| Leader–member exchange (LMX) |

| LMX1. I usually know whether or not my leader is satisfied with what I do. |

| LMX2. My leader understands my job problems and needs very well. |

| LMX3. My leader recognizes my potential very well. |

| LMX4. At the workplace, my leader would help me to solve difficult problems. |

| LMX5. At the workplace, my leader would “bail me out” at their expense. |

| LMX6. I have enough confidence in my leader that I would defend and justify their decision if they were not present to do so. |

| LMX7. I have very good relationships with my leader. |

| Work engagement scale |

| WE1. I spend a lot of time thinking about my work. |

| WE2. When I am working, I often lose track of time. |

| WE3. When I am working, I am completely engrossed by my work. |

| WE4. Nothing can distract me when I am working. |

| WE5. I concentrate a lot on my work. |

| WE6. I pay a lot of attention to my work. |

| Adjustment-specific scale |

| Task mastery (TM) |

| TM1. I have developed adequate skills and abilities to perform my present job within this organization. |

| TM2. I have developed adequate knowledge required in my present job. |

| TM3. I complete most of my present work assignments without assistance. |

| TM4.I rarely make mistakes when conducting my job assignments. |

| Fitting in (FI) |

| FI1.Accepting the pivotal values (e.g., what is important and what is not) of most others in this hotel. |

| FI2. Accepting the common attitudes (toward work) of most others in this hotel. |

| FI3. Accepting the main ideas of most others in this hotel. |

| FI4. Accepting the pivotal organizational norms (e.g., what one should and should not do in this organizational context) followed by most others here. |

| FI5. Accepting practices and customs commonly found in this hotel. |

| Standing out (SO) |

| SO1. Doing the job better than others in this organization. |

| SO2. Acting more professionally than other co-workers here. |

| SO3. Gaining my personal competitive advantage over other co-workers in this hotel. |

| Role negotiation (RN) |

| RN1. Negotiating with supervisors/co-workers about my desirable job assignment. |

| RN2. Negotiating with my supervisors/co-workers about my desirable job changes (e.g., job rotations, shift changes, and the likes). |

| RN3. Reaching mutual agreement with my supervisors/co-workers on the job demand (e.g., requirements in a job description) placed on me. |

| RN4. Adjusting my work role to best suit my talents and needs. |

| RN5. Being allowed by supervisors/co-workers to use my own way to achieve higher job performances. |

| Membership identification (MI) |

| MI1. I am proud to be an employee of this hotel. |

| MI2. I value being a member of this organization. |

| MI3. I have a warm feeling towards this hotel as a workplace. |

| Interpersonal relationships (IR) |

| IR1. I get on well with others in this hotel. |

| IR2. I feel people in this organization really care about me. |

| IR3. Most people in my hotel respect me. |

| IR4. I have a lot of good friends in this hotel. |

| IR5. Overall, I have established a good “guanxi” (interpersonal relationships) with most other people in this hotel. |

References

- Saks, A.M. Translating employee engagement research into practice. Organ. Dyn. 2017, 46, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anasori, E.; Bayighomog, S.W.; De Vita, G.; Altinay, L. The mediating role of psychological distress between ostracism, work engagement, and turnover intentions: An analysis in the Cypriot hospitality context. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanein, F.; Özgit, H. Sustaining human resources through talent management strategies and employee engagement in the Middle East hotel industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiul, M.K.; Patwary, A.K.; Panha, I.M. The role of servant leadership, self-efficacy, high performance work systems, and work engagement in increasing service-oriented behavior. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2022, 31, 504–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z. The Antecedents and Consequences of Socilizees’ Adjustment during Their Organizational Assimilation: An Integrative Study. Ph.D. Thesis, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Kowloon, Hong Kong, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, S.L.; Bakker, A.B.; Gruman, J.A.; Macey, W.H.; Saks, A.M. Employee engagement, human resource management practices and competitive advantage. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2015, 2, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M.; Gruman, J.A. Socialization resources theory and newcomers’ work engagement: A new pathway to newcomer socialization. Career Dev. Int. 2018, 23, 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Chon, K.; Ding, G.; Gu, C. Impact of organizational socialization tactics on newcomer job satisfaction and engagement: Core self-evaluations as moderators. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 46, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, K.K.; Oetzel, J.G. Exploring the dimensions of organizational assimilation: Creating and validating a measure. Commun. Q. 2003, 51, 438–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallup. State of the Global Workplace Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.gallup.com/workplace/349484/state-of-the-global-workplace.aspx? (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Asghar, M.; Tayyab, M.; Gull, N.; Song, Z.; Shi, R.; Tao, X. Polychronicity, work engagement, and turnover intention: The moderating role of perceived organizational support in the hotel industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 49, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, J.X.; Beenen, G.; Gagné, M.; Dunlop, P.D. Satisfying newcomers’ needs: The role of socialization tactics and supervisor autonomy support. J. Bus. Psychol. 2021, 36, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Yao, L.; Jia, X. Mentoring and newcomer well-being: A socialization resources perspective. J. Manag. Psychol. 2021, 36, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.N.; Bodner, T.; Erdogan, B.; Truxillo, D.M.; Tucker, J.S. Newcomer adjustment during organizational socialization: A meta-analytic review of antecedents, outcomes, and methods. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahari, N.; Kaliannan, M. Antecedents of work engagement in the public sector: A systematic literature review. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.P.; Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B.; Uhl-Bien, M. Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Van Den Heuvel, M. Leader-member exchange, work engagement, and job performance. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 754–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarandopoulos, L.; Bordia, P. Resource Passageways and Caravans: A multi-level, multi-disciplinary review of the antecedents of resources over the Lifespan. Work Aging Retire. 2022, 8, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radstaak, M.; Hennes, A. Leader-member exchange fosters work engagement: The mediating role of job crafting. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2017, 43, a1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.Q.; Kim, B.C.; Milne, S. Leader–member exchange (LMX) and its work outcomes: The moderating role of gender. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2017, 26, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Chathoth, P.K.; Chon, K. Measuring employees’ assimilation-specific adjustment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1968–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Chathoth, P.K. Core self-evaluations and job performance: The mediating role of employees’ assimilation-specific adjustment factors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesener, T.; Gusy, B.; Jochmann, A.; Wolter, C. The drivers of work engagement: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal evidence. Work Stress 2020, 34, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantabutra, S.; Ketprapakorn, N. Toward a theory of corporate sustainability: A theoretical integration and exploration. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xerri, M.J.; Cozens, R.; Brunetto, Y. Catching Emotions: The moderating role of emotional contagion between leader-member exchange, psychological capital and employee well-being. Pers. Rev. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelebek, E.E.; Alniacik, E. Effects of leader-member exchange, organizational identification and leadership Communication on unethical pro-organizational behavior: A study on bank employees in Turkey. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbard, N.P. Enriching or depleting? The dynamics of engagement in work and family roles. Adm. Sci. Q. 2001, 46, 655–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.; Encarnação, T.; Viseu, J.; Sousa, M.J. Job Crafting and Job Performance: The mediating effect of engagement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Identifying organizational subcultures: An empirical approach. J. Manag. Stud. 1998, 35, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minsky, B.D. LMX Dyad Agreement: Construct Definition and the Role Supervisor/Subordinate Similarity and Communication in Understanding LMX. Ph.D. Thesis, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jokisaari, M.; Nurmi, J.E. Change in newcomers’ supervisor support and socialization outcomes after organizational entry. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis, 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, H.A.; Simmering, M.J.; Sturman, M.C. A tale of three perspectives: Examining post hoc statistical techniques for detection and correction of common method variance. Organ. Res. Methods 2009, 12, 762–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, T.L.P. Income and quality of life: Does the love of money make a difference? J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 72, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantabutra, S. Exploring relationships among sustainability organizational culture components at a leading Asian industrial conglomerate. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantabutra, S.; Ketprapakorn, N. Toward an organizational theory of resilience: An interim struggle. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, G.T.; O’Leary-Kelly, A.M.; Wolf, S.; Klein, H.J.; Gardner, P.D. Organizational socialization: Its content and consequences. J. Appl. Psychol. 1994, 79, 730. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1995-07759-001 (accessed on 19 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development Theory and Applications; Applied Social Research Methods Series; Brickman, L., Rog, D.J., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).