Achieving SDG 4, Equitable Quality Education after COVID-19: Global Evidence and a Case Study of Kazakhstan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Global Evidence on Equitable Quality Distance Education during COVID-19

2.1. Digital Infrastructure

2.2. Policy Guidelines

2.3. Professional Development in Distance Pedagogy

2.4. The Home Environment

2.5. Teacher Pedagogy

2.5.1. Teacher Knowledge of Digital Pedagogy

2.5.2. Teachers’ Pedagogic Practices

2.5.3. Students’ Outcomes

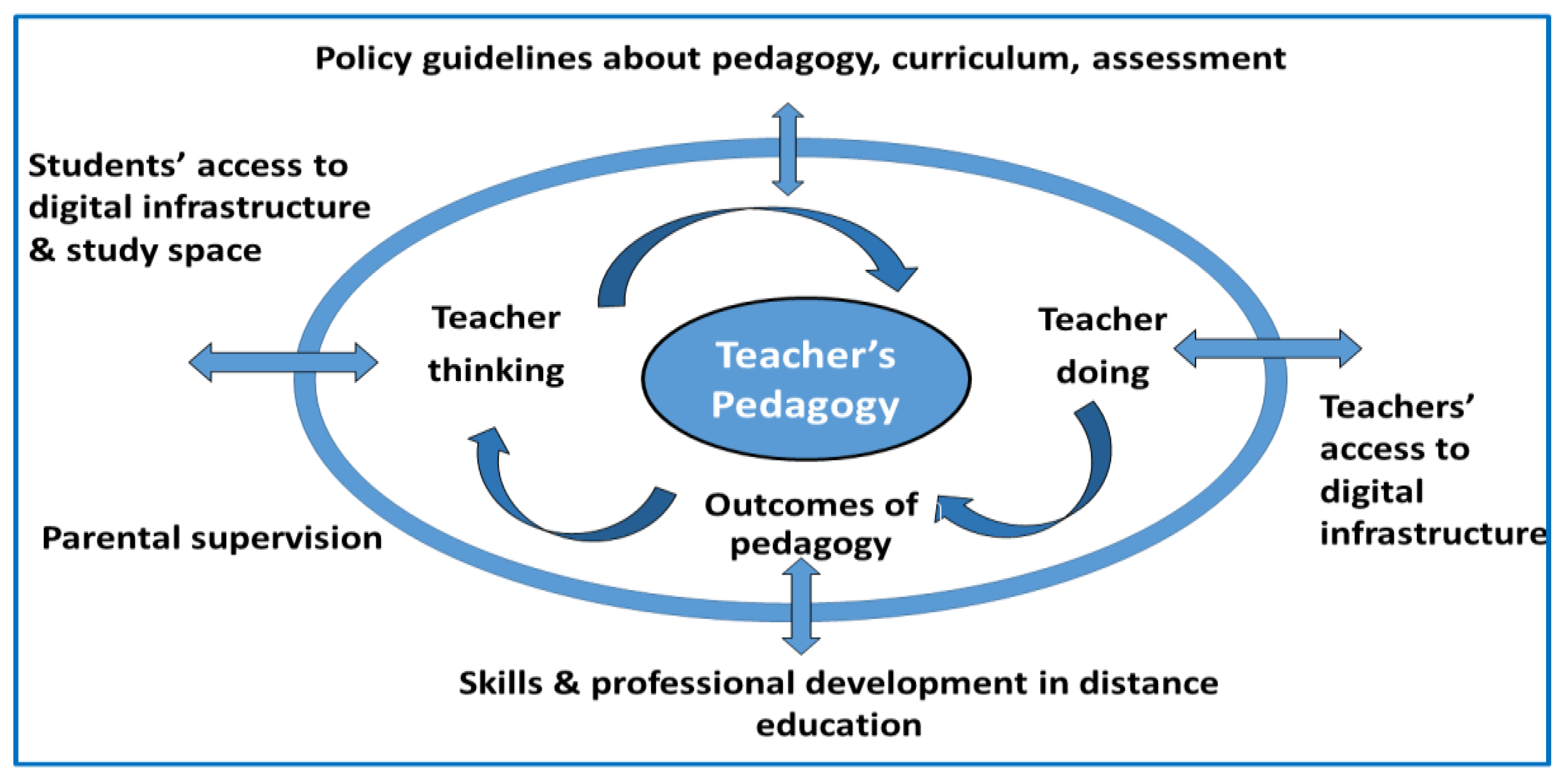

3. Conceptual Framework for Equitable Quality Distance Education

- Teacher thinking: sound knowledge of the principles of distance education, knowledge of the curriculum and an empathetic understanding of the child’s home environment;

- Teacher doing: giving instruction and offering a digitally imaginative explanation; using varying levels of questioning, elaboration, digital materials and platforms; creating a positive emotional and social environment for students; and flexibly using whole-class, group and pair work and interaction;

- Outcomes of pedagogy: monitoring student engagement, participation and motivation online; reviewing and supporting students’ work and offering timely constructive feedback; and assessing student outcomes through online tests and assignments.

- Effective online education presupposes access to digital devices, platforms and learning resources and stable internet for students and teachers;

- Quality distance schooling requires policy regarding timetable, curriculum coverage and modes and frequency of assessment;

- Exclusive distance teaching requires continued professional development for teachers in distance pedagogy;

- Since effective distance schooling relies on the active support of the family, teachers and schools must pay close attention to the variation in home environments in access to digital infrastructure, quiet study space and parental supervision.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. The Case Study Background

4.2. Research Questions, Design and Methods

- How are research participants’ experiences of distance education shaped by four supporting factors: digital infrastructure, policy guidelines, teacher professional development and the home environment?

- What are the research participants’ experiences of teacher pedagogy during distance schooling?

- How are research participants’ experiences of distance education differentiated across intersectional markers of disadvantage, namely, school type, rural vs. urban location, gender, family status, socio-economic background, grade and age?

4.3. Participants and Research Sites

4.4. Data Analysis

4.5. Data Validation

5. Results

5.1. Access to Digital Infrastructure

5.1.1. Digital Devices

5.1.2. Internet

5.1.3. Learning Materials and Platforms

‘Currently, we use the MS Teams platform. Therefore, all pertinent data and content were made available exclusively through this platform.’(T25_Almaty_elite school _urban)

‘Even the costly books required for teaching purposes were promptly procured.’(T19_Shymkent_elite school _urban)

5.2. Policy Guidelines during Distance Schooling

‘The methodological support to facilitate the learning process was provided at an exemplary level. Any questions or concerns were promptly addressed through open discussions. Moreover, both the school’s IT service and informatics teachers were readily available to assist in resolving any issues that might arise, regardless of the time.’(T24_Almaty_elite school_urban)

5.3. Teacher Professional Development

‘The school administration prioritises professional development and has organised numerous webinars for teachers through the Center for Pedagogical Excellence. Additionally, the Methodological Association of Informatics has arranged various events that have proven to be highly beneficial. Moreover, many teachers from our school have taken courses tailored to the Microsoft Teams platform, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of online learning facilitated by Microsoft.’(T25_Almaty_elite school_urban)

‘Education departments conducted a series of webinars designed to offer methodological support to teachers for effective distance learning. Furthermore, all teachers participated in a specialised course that equipped them with the necessary skills and knowledge to implement distance education successfully.’(T27_Almaty_rural)

5.4. Diversity in Home Environment

5.4.1. Study Space

‘While my siblings studying in the morning are busy with their lessons, those of us with afternoon classes assist our mother with household tasks. Similarly, when the afternoon shift begins their lessons, the morning shift takes charge of household chores. This requires discipline and time management from everyone involved.’(S13_ Shymkent_semi-urban_girl_grade 8)

‘The child having lessons isolates themselves by locking their room. The rest of us stay in the other room together to avoid causing distraction. The little ones are not allowed to play around or make a noise during this time.’(P5_Astana_urban_male)

5.4.2. Parental Supervision

‘Due to my husband’s work schedule, he leaves in the morning and returns in the evening, leaving him with limited availability to contribute. There are instances when even I struggle to find time due to my household chores, resulting in homework occasionally being left undone during those periods.’(T17_Shymkent_rural)

5.5. Distance Pedagogy

5.5.1. Teacher Thinking

5.5.2. Teacher Doing

‘We use the Online Mektep platform for our studies; however, it lacks content for certain subjects like Physics. Therefore, I take it upon myself to prepare the necessary materials and presentations on this topic for the children. I explain the lessons using Google Meet and share tasks with them via WhatsApp. The children review these assignments and cross-reference the Kazakh version on the Online Mektep platform. I can also provide individual assignments in English through Google Forms [Science subjects in secondary school are taught in English].’(T2_Astana_rural)

‘During our experience of teaching remotely, we acquired the skills to deliver lessons both asynchronously and synchronously. However, due to the limitations of poor network connectivity, we cannot use platforms that would be ideal for interacting with the children. As a result, we rely primarily on WhatsApp as the means of communication and teaching.’(T11_Shymkent_rural)

‘The teacher simply sends the video for us to watch. And then, he asks us to complete the tasks in Online Mektep. But I do not understand anything from the videos he sends.’(S11_Shymkent_urban_boy_ grade 8)

5.5.3. Outcomes of Pedagogy

‘In my opinion, many students who lacked motivation in traditional school settings now face even greater challenges in maintaining their motivation. This makes the learning process particularly difficult. Also, some parents cannot monitor their children throughout the day due to work commitments. As a result, children may be left to navigate online learning independently at home.’(T7_Almaty_ _rural)

‘A high-performing, excellent student became less active … He is alone, and his parents are at work.’(T4_Astana_semi urban)

‘They likely cheat, but I turn a blind eye to this.’(T21_Almaty_elite school_urban_male)

‘While it may not be possible to copy each other’s tests when attending school in person, distance learning has allowed us to help and support each other in different ways.’(S9_Astana_semi-urban _girl_grade 7)

‘They cheat anyway; they copy each other’s assessment tasks.’(P29_Almaty_urban)

6. Discussion

6.1. Study Implications

6.1.1. Bringing Teaching and Learning Processes to the Core of SDG 4 Measurement

6.1.2. Investment in Digital Equity

6.1.3. Teacher Education for Digital Pedagogies in Support of SDG 4

6.1.4. Intersectional Disadvantage

6.2. Limitations and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Categories | Codes | Illustrative Interview Excerpts |

|---|---|---|

| Gadgets | Smartphone | Then it is hard to study with one mobile phone, yes. (T18) |

| Laptop/desktop | The students, those who were in need who did not have a computer, were given laptops. (T25) | |

| Platforms | Online Mektep | Online Mektep, as you know, just requires completing tasks. Just completing tasks, and that’s it. (T21) |

| Zoom | Sometimes, we study using ZOOM (S27) | |

| Bilimland | Sometimes, when the teacher is busy, or something is wrong with the teacher, we have assignments in Bilimland. (S27) | |

| MS Teams | Currently, we use the MS Teams platform. And so, absolutely everything on this platform, all the information, was provided. (T25) | |

| Digital materials | Textbooks | We did not get these textbooks either electronically or otherwise (P7) |

| Web information | They are still looking for materials, surfing the internet all the time, and looking for something to do their homework, right? (P4) | |

| Videos | They also sent the YouTube links. There are so many videos on YouTube! (P15) | |

| Internet | No access | I do not have a network, even at my house. (T17) |

| Poor bandwidth | We have a poor internet connection since we live on the outskirts of a small village. (T18) | |

| Strong bandwidth | It is easy for the child to study at home; the child downloads from the internet quickly and completes the work quickly. (P13) |

References

- UNESCO. Global Education Monitoring Report, 2021/2: Non-state Actors in Education: Who Chooses? Who Loses, 2nd ed.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379875_eng (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Patrinos, H.A. The longer students were out of school, the less they learned. J. Sch. Choice 2023, 17, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, R.J. Teaching and learning for all? The quality imperative revisited. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2015, 40, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, Y.; Moriarty, K. SDG 4 and the ‘education quality turn’: Prospects, possibilities, and problems. In Grading Goal Four: Threats, and Opportunities in Sustainable Development Goal on Quality Education; Wulff, A., Ed.; BRILL: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 194–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traub-Schmidt, G. The SDGs can guide our recovery. In Sustainable Development Goals: Building Back Better; Carver, F., Ed.; Witan Media Ltd: Painswick, UK, 2020; pp. 74–76. Available online: https://una.org.uk/sustainable-development-goals-building-back-better#:~:text=UNA%2DUK%20has%20launched%20a,of%20leaving%20no%20one%20behind.&text=With%20an%20introduction%20from%20Deputy%20Secretary%2DGeneral%20Amina%20J (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- Durrani, N.; Helmer, J.; Polat, F.; Qanay, G. Education, Gender and Family Relationships in the Time of COVID-19: Kazakhstani Teachers’, Parents’ and Students’ Perspectives; Partnerships for Equity and Inclusion (PEI) Pilot Project Report; Graduate School of Education, Nazarbayev University: Astana, Kazakhstan, 2021; Available online: https://research.nu.edu.kz/en/publications/education-gender-and-family-relationships-in-the-time-of-COVID-19 (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Tabaeva, A.; Ozawa, V.; Durrani, N.; Thibault, H. The Political Economy of Society and Education in Central Asia: A Scoping Literature Review; The PEER Network: Astana, Kazakhstan, 2021; Available online: https://peernetworkgcrf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Scoping-Review_Final_23-June-2021.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Hosszu, A.; Rughiniș, C. Digital divides in education: An analysis of the Romanian public discourse on distance and online education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rom. Sociol./Sociol. Rom. 2020, 18, 11–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinidad, J.O. Equity, engagement, and health: School organizational issues and priorities during COVID-19. J. Educ. Adm. Hist. 2021, 53, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterbrook, M.J.; Doyle, L.; Grozev, V.H.; Kosakowska-Berezecka, N.; Harris, P.R.; Phalet, K. Socioeconomic and gender inequalities in home learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Examining the roles of the home environment, parent supervision, and educational provisions. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2023, 40, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, T.; Warschauer, M. Equity in online learning. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 57, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haser, Ç.; Oğuzhan, D.; Erhan, G.K. Tracing students’ mathematics learning loss during school closures in teachers’ self-reported practices. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2022, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palau, R.; Fuentes, M.; Mogas, J.; Cebrián, G. Analysis of the implementation of teaching and learning processes at Catalan schools during the COVID-19 lockdown. Technol. Pedag. Educ. 2021, 30, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, A.; Cattan, S.; Costa Dias, M.; Farquharson, C.; Kraftman, L.; Krutikova, S.; Phimister, A.; Sevilla, A. Learning during the Lockdown: Real-Time Data on Children’s Experiences during Home Learning; The Institute for Fiscal Studies: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jæger, M.M.; Blaabæk, E.H. Inequality in learning opportunities during COVID-19: Evidence from library takeout. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2020, 68, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmigiani, D.; Benigno, V.; Giusto, M.; Silvaggio, C.; Sperandio, S. E-inclusion: Online special education in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2020, 30, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.; Sanchez Tapia, I.; Baird, S.; Guglielmi, S.; Oakley, E.; Yadete, W.A.; Sultan, M.; Pincock, K. Intersecting barriers to adolescents’ educational access during COVID-19: Exploring the role of gender, disability and poverty. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2021, 85, 102428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schechter, C.; Da’as, R.; Qadach, M. Crisis leadership: Leading schools in a global pandemic. Manag. Educ. 2022, 11, 08920206221084050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham, P.; Harriott, T.; Healy, G.; Arenge, G.; Wilson, E. Pressures and influences on school leaders navigating policy development during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 48, 201–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grooms, A.A.; Childs, J. “We Need to Do Better by Kids”: Changing Routines in U.S. Schools in Response to COVID-19 School Closures. J. Educ. Stud. Placed Risk 2021, 26, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, L.S.; Kaufman, J.H.; Diliberti, M. Teaching and Leading through a Pandemic: Key Findings from the American Educator Panels Spring 2020 COVID-19 Surveys. Data Note: Insights from the American Educator Panels; Research Report. RR-A168-2; RAND Corparation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosaretsky, S.; Zair-Bek, S.; Kersha, Y.; Zvyagintsev, R. General education in Russia during COVID-19: Readiness, policy response, and lessons learned. In Primary and Secondary Education during COVID-19: Disruptions to Educational Opportunity during a Pandemic; Reimers, F.M., Ed.; Springer Cham: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 227–263. [Google Scholar]

- Demeshkant, N.; Schultheis, K.; Hiebl, P. School sustainability and school leadership during crisis remote education: Polish and German experience. Comput. Sch. 2022, 39, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa Díaz, M.J. Emergency remote education, family support and the digital divide in the context of the COVID-19 lockdown. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khlaif, Z.N.; Salha, S.; Affouneh, S.; Rashed, H.; ElKimishy, L.A. The COVID-19 epidemic: Teachers’ responses to school closure in developing countries. Technol. Pedag. Educ. 2020, 30, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, L.A.; Cooper, H.B. Technology-enabled remote learning during COVID-19: Perspectives of Australian teachers, students and parents. Technol. Pedag. Educ. 2021, 30, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhari, B.; Fajri, I. Distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: School closure in Indonesia. Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 53, 1934–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, J.; Jäger-Biela, D.J.; Glutsch, N. Adapting to online teaching during COVID-19 school closure: Teacher education and teacher competence effects among early career teachers in Germany. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 43, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trust, T.; Whalen, J. Should teachers be trained in emergency remote teaching? Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 2020, 28, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, A.B.M.; Chan, C.K.K.; Harfitt, G.; Leung, P. Crisis and opportunity in teacher preparation in the pandemic: Exploring the “adjacent possible”. J. Prof. Cap. Community 2020, 5, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R.; Morris, K.; Hofmeyr, J. Education, Inequality, and Innovation in the Time of COVID-19; JET Education Services: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2020; pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhow, C.; Lewin, C.; Staudt Willet, K.B. The educational response to COVID-19 across two countries: A critical examination of initial digital pedagogy. Technol. Pedag. Educ. 2021, 30, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Verma, A. An exploratory assessment of the educational practices during COVID-19. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2021, 29, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikas, S.; Mathur, A. An empirical study of student perception towards pedagogy, teaching style and effectiveness of online classes. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 589–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mælan, E.N.; Gustavsen, A.M.; Stranger- Johannessen, E.; Nordahl, T. Norwegian students’ experiences of homeschooling during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2021, 36, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubb, S.; Jones, M.A. Learning from the COVID-19 homeschooling experience: Listening to pupils, parents/carers and teachers. Improv. Sch. 2020, 23, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, D.; Dunn, J. We’re all teachers now: Remote learning during COVID-19. J. Sch. Choice 2020, 14, 567–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsbury, I. Online learning: How do brick and mortar schools stack up to virtual schools? Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 6567–6588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Cappelle, F.; Chopra, V.; Ackers, J.; Gochyyev, P. An analysis of the reach and effectiveness of distance learning in India during school closures due to COVID-19. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2021, 85, 102439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedoyin, O.B.; Soykan, E. COVID-19 pandemic and online learning: The challenges and opportunities. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 31, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, A.; Starkey, L.; Egerton, B.; Flueggen, F. High school students’ experience of online learning during COVID-19: The influence of technology and pedagogy. Technol. Pedag. Educ. 2020, 30, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounjid, B.; El Hilali, E.; Amrani, F.; Moubtassime, M. Teachers’ perceptions and the challenges of online teaching/learning in Morocco during COVID-19 crisis. Arab World Engl. J. 2021, 7, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herreid, C.F.; Prud’homme-Genereux, A.; Wright, C.; Schiller, N.; Herreid, K.F. Survey of case study users during pandemic shift to remote instruction. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2021, 45, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, N. Teachers as students: Adapting to online methods of instruction and assessment in the age of COVID-19. Electron. J. Res. Sci. Math. Educ. 2020, 24, 168–171. [Google Scholar]

- Rahim, A.F.A. Guidelines for online assessment in emergency remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Med. J. 2020, 12, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrist, N.; de Barros, A.; Bhula, R.; Chakera, S.; Cummiskey, C.; DeStefano, J.; Floretta, J.; Kaffenberger, M.; Piper, B.; Stern, J. Building back better to avert a learning catastrophe: Estimating learning loss from COVID-19 school shutdowns in Africa and facilitating short-term and long-term learning recovery. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2021, 84, 102397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, J.P.; Gutierrez, M.; Hoyos, R.D.; Saavedra, J. The unequal impacts of COVID-19 on student learning. In Primary and Secondary Education during COVID-19: Disruptions to Educational Opportunity during a Pandemic; Reimers, F.M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 421–459. [Google Scholar]

- Monroy-Gómez-Franco, L.; Vélez-Grajales, R.; López-Calva, L.F. The potential effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on learning. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2022, 91, 102581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engzell, P.; Frey, A.; Verhagen, M.D. Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2022376118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haelermans, C.; Korthals, R.; Jacobs, M.; de Leeuw, S.; Vermeulen, S.; van Vugt, L.; Aarts, B.; Prokic-Breuer, T.; van der Ve Sharp, R. Increase in inequality in education in times of the COVID-19-pandemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, R.J. Culture and Pedagogy: International Comparisons in Primary Education; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Westbrook, J.; Durrani, N.; Brown, R.; Orr, D.; Pryor, J.; Boddy, J.; Salvi., F. Pedagogy, Curriculum, Teaching Practices and Teacher Education in Developing Countries: Final Report; Centre for International Education, University of Sussex: Sussex, UK, 2013; Available online: https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=3433 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Carbado, D.W.; Crenshaw, K.W.; Mays, V.M.; Tomlinson, B. Intersectionality: Mapping the movements of a theory. Du Bois Rev. 2013, 10, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, H.Y.; Ferree, M.M. Practicing intersectionality in sociological research: A critical analysis of inclusions, interactions, and institutions in the study of inequalities. Sociol. Theory 2010, 28, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimranova, A.; Shamatov, D.; Sharplin, E.; Durrani, N. Education in Kazakhstan. In Education Systems Entering the Twenty-First Century; Wolhuter, C.C., Steyn, H.J., Eds.; Keurkopie: Noordbrug, South Africa, 2021; pp. 404–438. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of National Statistics of the Agency for Strategic Planning and Reform of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Basic and General Secondary Education. Available online: https://stat.gov.kz/official/industry/62/statistic/7 (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Afzal Tajik, M.; Shamatov, D.; Fillipova, L. Stakeholders’ perceptions of the quality of education in rural schools in Kazakhstan. Improv. Sch. 2022, 25, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chankseliani, M.; Gorgodze, S.; Janashia, S.; Kurakbayev, K. Rural disadvantage in the context of centralised university admissions: A multiple case study of Georgia and Kazakhstan. Comp. A J. Compar. Int. Educ. 2020, 50, 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD; UNICEF. Education in Eastern Europe and Central Asia: Findings from PISA; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. A New Generation: 25 Years of Efforts for Gender Equality in Education. Gender Report of the Global Education Monitoring Report 2020; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374514 (accessed on 18 September 2021).

- Bokayev, B.; Torebekova, Z.; Davletbayeva, Z.; Zhakypova, F. Distance learning in Kazakhstan: Estimating parents’ satisfaction of educational quality during the coronavirus. Techn. Pedag. Educ. 2021, 30, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokayev, B.; Torebekova, Z.; Abdykalikova, M.; Davletbayeva, Z. Exposing policy gaps: The experience of Kazakhstan in implementing distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2021, 15, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajar, A.; Manan, S.A. Young children’s perceptions of emergency online English learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from Kazakhstan. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2023, 17, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirova, A.; Nurumov, K.; Kasa, R.; Akhmetzhanova, A.; Kuzekova, A. The impact of the digital divide on synchronous online teaching in Kazakhstan during COVID-19 school closures. Front. Educ. 2023, 7, 1083651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S.B.; Tisdell, E.J. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-119-00365-6. [Google Scholar]

- Boddy, C.R. Sample Size for Qualitative Research. Qual. Mark. Res. 2016, 19, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4129-7212-3. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Bureau of National Statistics. Number of Teachers of Secondary Schools. Available online: https://stat.gov.kz/official/industry/62/statistic/8 (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Yaremych, H.E.; Persky, S. Recruiting fathers for parenting research: An evaluation of eight recruitment methods and an exploration of fathers’ motivations for participation. In Parenting; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2022; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtman, M. Qualitative Research in Education: A User’s Guide; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. Coding and analysis strategies. In The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research; Leavy, P., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 581–605. [Google Scholar]

- Abmayr, B.; Caprette, D.R.; Gopalan, C. Flipped teaching eased the transition from face-to-face teaching to online instruction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2021, 45, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akabayashi, H.; Taguchi, S.; Zvedelikova, M. Access to and demand for online school education during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2023, 96, 102687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addi-Raccah, A.; Seeberger Tamir, N. Mothers as teachers to their children: Lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Fam. Stud. 2023, 29, 1379–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schools in Kazakhstan Are Going to Teach New Subject. Available online: https://kz.kursiv.media/en/2021-10-12/schools-kazakhstan-are-going-teach-new-subject/ (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Teacher Shortage Reduction Program Presented. Available online: https://kazmkpu.kz/en/a/news/1050-predstavlena-programma-po-snizheniyu-defitsita-uchitelej (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- The Ministry of Education of the RK Is Developing the Concept of Rural School Improvement [KR Oku-Agartu Ministrligi Ayul Mektepterin Damitu Tukyrymdamasyn Azirlep Jatir]. Available online: https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/edu/press/news/details/557966?lang=kk (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Askhat Aimagambetov Spoke about Giving Academic Freedom to Kazakhstani Schools [Askhat Aymagambetov Kazakhstandik Mektemterge Akademiyalyk Erkindik Beru Turaly Aittytwralı Ayttı]. Available online: https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/edu/press/news/details/484482?lang=kk (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Launching the Project to Develop the Potential of Ungraded Schools [Shagyn Jinaktyk Auldyk Mektepterdin Aleuetin Damytu Jobasy Iske Kosyldy]. Available online: https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/edu/press/news/details/603104?lang=kk (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Helmer, J.; Kasa, R.; Somerton, M.; Makoelle, T.M.; Hernández-Torrano, D. Planting the seeds for inclusive education: One resource centre at a time. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2023, 27, 586–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, H.A.; Caringi, J.C.; Pyles, L.; Jurkowski, J.M.; Bozlak, C.T. Participatory Action Research. Pocket Guide to Social Work Research; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Boeren, E. Understanding Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 on “quality education” from micro, meso and macro perspectives. Int. Rev. Educ. 2019, 65, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stakeholders (Method) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research Site | Teachers Interview | Parents Interview | Students FGDs * | Total |

| Almaty Region | 10 | 10 | 8 (2) | 28 |

| Astana | 10 | 10 | 10 (2) | 30 |

| Shymkent | 10 | 10 | 10 (2) | 30 |

| Total | 30 | 30 | 28 (6) | 88 |

| Stakeholder | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Teachers (n = 30) | Parents (n = 30) | Students (n = 28) | |

| School type | ||||

| Public | 25 | N/A | 24 | |

| Elite | 5 | N/A | 4 | |

| Location | ||||

| Rural | 12 | 3 | 5 | |

| Semi-urban | 6 | 13 | 11 | |

| Urban | 12 | 14 | 12 | |

| Stakeholders | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Teachers (n = 30) | Parents (n = 30) | Students (n = 28) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 26 | 29 | 16 |

| Male | 4 | 1 | 12 |

| Family status | |||

| Single | 2 | N/A | N/A |

| Single parent | 6 | 12 | 6 |

| Nuclear family | 19 | 13 | 16 |

| Extended family | 3 | 5 | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Durrani, N.; Qanay, G.; Mir, G.; Helmer, J.; Polat, F.; Karimova, N.; Temirbekova, A. Achieving SDG 4, Equitable Quality Education after COVID-19: Global Evidence and a Case Study of Kazakhstan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014725

Durrani N, Qanay G, Mir G, Helmer J, Polat F, Karimova N, Temirbekova A. Achieving SDG 4, Equitable Quality Education after COVID-19: Global Evidence and a Case Study of Kazakhstan. Sustainability. 2023; 15(20):14725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014725

Chicago/Turabian StyleDurrani, Naureen, Gulmira Qanay, Ghazala Mir, Janet Helmer, Filiz Polat, Nazerke Karimova, and Assel Temirbekova. 2023. "Achieving SDG 4, Equitable Quality Education after COVID-19: Global Evidence and a Case Study of Kazakhstan" Sustainability 15, no. 20: 14725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014725

APA StyleDurrani, N., Qanay, G., Mir, G., Helmer, J., Polat, F., Karimova, N., & Temirbekova, A. (2023). Achieving SDG 4, Equitable Quality Education after COVID-19: Global Evidence and a Case Study of Kazakhstan. Sustainability, 15(20), 14725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014725