Environmental Information: Different Sources Different Levels of Pro-Environmental Behaviours?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Role of Information and Information Sources for PEB

2.2. The Role of Sociodemographic Variables for PEB

3. Data and Methods

4. Results

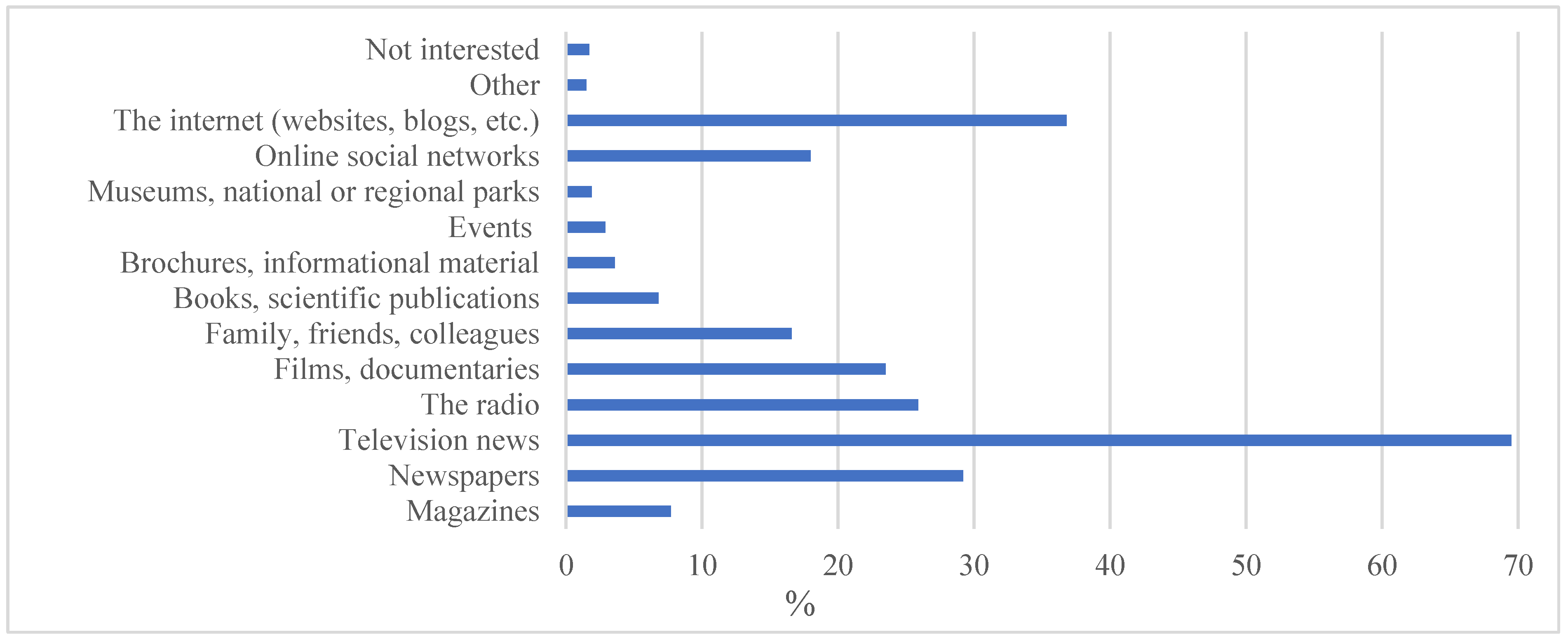

4.1. Sources for the Environmental Information

4.2. Level of Pro-Environmental Behaviours

4.3. Determinants for Pro-Environmental Behaviours

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iwińska, K.; Bieliński, J.; Calheiros, C.S.C.; Koutsouris, A.; Kraszewska, M.; Mikusiński, G. The primary drivers of private-sphere pro-environmental behaviour in five European countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 393, 136330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A European Strategy for Plastics in a Circular Economy. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Brussels, 16 January 2018, COM (2018) 28 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2018:28:FIN (accessed on 7 September 2023).

- European Commission. European Climate Pact. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Brussels, COM (2020) 788 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2020%3A788%3AFIN (accessed on 7 September 2023).

- Paço, A.; Lavrador, T. Environmental knowledge and attitudes and behaviours towards energy consumption. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 197, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Cai, L.; Sun, F.; Li, G.; Che, Y. Public attitudes towards microplastics: Perceptions, behaviors and policy implications. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 163, 105096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakučionytė-Skodienė, M.; Liobikienė, G. Changes in energy consumption and CO2 emissions in the Lithuanian household sector caused by environmental awareness and climate change policy. Energy Policy 2023, 180, 113687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, A.; Giaccherini, M.; Zoli, M. The Role of Information Sources and Providers in Shaping Green Behaviors. Evidence from Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 164, 106292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Minelgaitė, A. Energy and resource-saving behaviours in European Union countries: The Campbell paradigm and goal framing theory approaches. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 750, 141745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.B.; Rice, R.E.; Gustafson, A.; Goldberg, M.H. Relationships Among Environmental Attitudes, Environmental Efficacy, and Pro-Environmental Behaviors Across and Within 11 Countries. Environ. Behav. 2022, 54, 1063–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, G.; Wilson, M. Goal-directed conservation behavior: The specific composition of a general performance. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 36, 1531–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimlich, J.E.; Ardoin, N.M. Understanding behavior to understand behavior change: A literature review. Environ. Educ. Res. 2008, 14, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Escario, J.J.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, C. Analyzing differences between different types of pro-environmental behaviors: Do attitude intensity and type of knowledge matter? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankenberg, A.-K.; Alhusen, H. On the Determinants of Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Literature Review and Guide for the Empirical Economist; Center for European, Governance, and Economic Development Research (CEGE): Göttingen, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. Strategies for Promoting Proenvironmental Behavior. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Fostering customers’ pro-environmental behavior at a museum. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 25, 1240–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. What influences water conservation and towel reuse practices of hotel guests? Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, N.J.; Cialdini, R.B.; Griskevicius, V. A Room with a Viewpoint: Using Social Norms to Motivate Environmental Conservation in Hotels. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Kaiser, F.G. Ecological behaviour across the lifespan: Why environmentalism increases as people grow older. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela-Candamio, L.; Novo-Corti, I.; García-Álvarez, M.T. The importance of environmental education in the determinants of green behavior: A meta-analysis approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 1565–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiiuk, Y.; Liobikienė, G. The role of financial, informational, and social tools on resource-saving behaviour in Lithuania: Assumptions and reflections of real situation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 326, 129378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Fan, W.; Kong, F. Does environmental information disclosure raise public environmental concern? Generalized propensity score evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, J.; Kaiser, F.G.; Wilson, M. Environmental knowledge and conservation behavior: Exploring prevalence and structure in a representative sample. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 37, 1597–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, K.; Stern, M.J. Messaging for environmental action: The role of moral framing and message source. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 68, 101394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, S. Information sources, perceived personal experience, and climate change beliefs. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, F.; Matthes, J. Nature Documentaries, Connectedness to Nature, and Pro-environmental Behavior. Environ. Commun. 2016, 10, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, Y. Impact of mass media on public awareness: The “Under the Dome” effect in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 173, 121145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.; Zhang, B.; Xu, J.; Lu, F. Mass media, information and demand for environmental quality: Evidence from the “Under the Dome”. J. Dev. Econ. 2020, 143, 102402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, C.; Winkler, A.C.; Childs, A.-R.; Muller, C.; Potts, W.M. Can social media platforms be used to foster improved environmental behaviour in recreational fisheries? Fish. Res. 2023, 258, 106544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junsheng, H.; Akhtar, R.; Masud, M.M.; Rana, M.S.; Banna, H. The role of mass media in communicating climate science: An empirical evidence. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238, 117934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareie, B.; Jafari Navimipour, N. The impact of electronic environmental knowledge on the environmental behaviors of people. Comput. Human Behav. 2016, 59, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Molina, M.A.; Fernández-Sainz, A.; Izagirre-Olaizola, J. Does gender make a difference in pro-environmental behavior? The case of the Basque Country University students. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Miceikienė, A. The role of financial, social and informational mechanisms on willingness to use bioenergy. Renew. Energy 2022, 194, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Juknys, R. The role of values, environmental risk perception, awareness of consequences, and willingness to assume responsibility for environmentally-friendly behaviour: The Lithuanian case. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3413–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J.; Vocino, A.; Grau, S.L.; Garma, R.; Ferdous, A.S. The impact of general and carbon-related environmental knowledge on attitudes and behaviour of US consumers. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 238–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, G.W.; Grunert, K.G.; Lähteenmäki, L. Chapter Seven—Supporting Consumers’ Informed Food Choices: Sources, Channels, and Use of Information. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2023, 104, 229–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi Sh Masini, A.; Aflaki, S.; Fahimnia, B. Right information at the right time: Reevaluating the attitude–behavior gap in environmental technology adoption. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 242, 108278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, T.M.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Z. Does media usage affect pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors? Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2022, 82, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbert, R.L.; Kwak, N.; Shah, D.V. Environmental Concern, Patterns of Television Viewing, and Pro-Environmental Behaviors: Integrating Models of Media Consumption and Effects. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2003, 47, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostman, R.E.; Parker, J.L. Impact of Education, Age, Newspapers, and Television on Environmental Knowledge, Concerns, and Behaviors. J. Environ. Educ. 1987, 19, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, J.C.; Shanahan, J. Skepticism About Media Effects Concerning the Environment: Examining Lomborg’s Hypotheses. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2004, 17, 861–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, N.; Wilson, J. I do it, but don’t tell anyone! Personal values, personal and social norms: Can social media play a role in changing pro-environmental behaviours? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 111, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, R.; Peterson, M.; Stevenson, K. How communication with teachers, family and friends contributes to predicting climate change behaviour among adolescents. Environ. Conserv. 2018, 45, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zeng, D.; Yang, B. Decomposing peer effects in pro-environmental behaviour: Evidence from a Chinese nationwide survey. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 295, 113100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Gao, Q.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X. What affects green consumer behavior in China? A case study from Qingdao. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagiliūtė, R.; Žaltauskaitė, J.; Sujetovienė, G. Self-reported behaviours and measures related to plastic waste reduction: European citizens’ perspective. Waste Manag. Res. 2023, 41, 1460–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Eurobarometer 92.4 (2019) GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA7602 Data File Version 1.0.0. Available online: https://search.gesis.org/research_data/ZA7602?doi=10.4232/1.13652 (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- European Commission. Attitudes of European Citizens towards the Environment. Report. Special Eurobarometer 501. European Union. 2020. p. 164. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2257 (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- de Groot, J.I.M.; Thøgersen, J. Values and Pro-Environmental Behaviour. In Environmental Psychology: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; Steg, L., de Groot, J.I.M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Luzzati, T.; Tucci, I.; Guarnieri, P. Information overload and environmental degradation: Learning from H.A. Simon W. Wenders. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 202, 107593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawden, D.; Holtham, C.; Courtney, N. Perspectives on information overload. Aslib Proc. 1999, 51, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Menéndez, L.; Cruz-Castro, L. The credibility of scientific communication sources regarding climate change: A population-based survey experiment. Public Underst. Sci. 2019, 28, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | % | Variable | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Age | ||

| Woman | 54.2 | 15–24 | 8.3 |

| Man | 45.8 | 25–34 | 12.3 |

| Household size | 34–44 | 14.9 | |

| 1 | 22.5 | 45–54 | 16.2 |

| 2 | 37.9 | 55–64 | 18.8 |

| 3 | 16.9 | 65 and more | 29.5 |

| 4 and more | 22.7 | Difficulties paying bills | |

| Type of community | Most of the time | 7.8 | |

| Rural area or village | 32.9 | From time to time | 24.5 |

| Small or middle-sized town | 38.5 | Almost never/never | 67.7 |

| Large town | 28.6 |

| Behaviour | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Chosen a more environmentally friendly way of travelling (walk, bicycle, public transport, electric car) | 0.28 | 0.449 |

| Avoided buying over-packaged products | 0.29 | 0.452 |

| Avoided single-use plastic goods other than plastic bags (e.g., plastic cutlery, cups, plates, etc.) or bought reusable plastic products | 0.44 | 0.497 |

| Separated most of your waste for recycling | 0.66 | 0.474 |

| Cut down your water consumption | 0.27 | 0.446 |

| Cut down your energy consumption (e.g., by turning down air conditioning or heating, not leaving appliances on stand-by, buying energy-efficient appliances) | 0.36 | 0.481 |

| Bought products marked with an environmental label | 0.22 | 0.416 |

| Bought local products | 0.44 | 0.496 |

| Used your car less by avoiding unnecessary trips, working from home (teleworking), etc. | 0.19 | 0.392 |

| Joined a demonstration, attended a workshop, taken part in an activity (e.g., a collective beach or park clean up) | 0.06 | 0.233 |

| Changed your diet to more sustainable food | 0.18 | 0.384 |

| Spoken to others about environmental issues | 0.30 | 0.460 |

| Bought second-hand products (e.g., clothes or electronics) instead of new ones | 0.21 | 0.405 |

| Repaired a product instead of replacing it | 0.31 | 0.463 |

| Variable | Television News | Other Internet (Websites, etc.) | Newspapers | Radio | Films, Documentaries | Online Social Networks | Family, Friends, Colleagues | Magazines | Books, Scientific Publications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender [women] | 0.195 | −0.158 | −0.106 | −0.006 | 0.023 | 0.11 | 0.185 | −0.013 | −0.252 |

| Age | 0.326 | −0.372 | 0.288 | 0.201 | −0.047 | −0.497 | −0.078 | 0.063 | −0.111 |

| Type of community | −0.137 | 0.111 | 0.071 | −0.149 | 0.120 | 0.09 | 0.015 | 0.039 | 0.245 |

| Household size | 0.068 | 0.092 | −0.002 | −0.062 | −0.002 | 0.107 | −0.003 | −0.012 | −0.044 |

| Incomes | −0.137 | 0.409 | 0.416 | 0.151 | 0.036 | 0.041 | −0.188 | 0.02 | 0.299 |

| Source of Environmental Information | Mean of Activities Performed | t Test | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicated as a Source | Not Indicated as a Source | |||

| Television news | 4.1 | 4.47 | −10.32 | <0.001 |

| Magazines | 4.36 | 4.2 | 2.505 | <0.05 |

| Radio | 4.37 | 4.15 | 5.57 | <0.001 |

| Films, documentaries | 4.93 | 3.99 | 24.13 | <0.001 |

| Family, friends, neighbours, or colleagues | 4.34 | 4.19 | 3.49 | <0.001 |

| Books, scientific publications | 5.99 | 4.09 | 29.07 | <0.001 |

| Brochures, informational material | 4.71 | 4.2 | 5.87 | <0.001 |

| Events (conferences, fairs, exhibitions, festivals, etc.), | 5.19 | 4.19 | 10.01 | <0.001 |

| Museums, national or regional parks | 4.41 | 4.21 | 1.56 | >0.05 |

| Online social networks | 4.55 | 4.14 | 9.37 | <0.001 |

| The internet (websites, blogs, forums, etc.) | 4.83 | 3.86 | 28.49 | <0.001 |

| Newspapers | 4.76 | 3.99 | 21.3 | <0.001 |

| Factor/Determinant | B Coefficient | SE | 95% CI | Wald Chi-Square | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Television news | 0.563 | 0.037 | 0.491; 0.637 | 228.27 | <0.001 |

| Magazines | 0.698 | 0.058 | 0.582; 0.807 | 147.08 | <0.001 |

| Radio | 0.926 | 0.037 | 0.857; 1.000 | 641.86 | <0.001 |

| Films, documentaries | 1.391 | 0.037 | 1.313; 1.458 | 1410.39 | <0.001 |

| Family, friends, neighbours, or colleagues | 0.931 | 0.042 | 0.845; 1.011 | 484.91 | <0.001 |

| Books, scientific publications | 2.238 | 0.062 | 2.107; 2.350 | 1300.04 | <0.001 |

| Brochures, informational material | 0.932 | 0.082 | 0.764; 1.084 | 130.84 | <0.001 |

| Events (conferences, fairs, exhibitions, festivals, etc.) | 1.357 | 0.092 | 1.164; 1.528 | 216.72 | <0.001 |

| Museums, national or regional parks | 0.664 | 0.112 | 0.434; 0.875 | 34.92 | <0.001 |

| Online social networks | 0.998 | 0.043 | 0.908; 1.077 | 537.40 | <0.001 |

| The internet (websites, blogs, forums, etc.) | 1.488 | 0.035 | 1.413; 1.550 | 1816.83 | <0.001 |

| Newspapers | 1.327 | 0.036 | 1.252; 1.391 | 1399.75 | <0.001 |

| Gender [women] | 0.366 | 0.030 | 0.425; 0.306 | 145.87 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.074 | 0.011 | 0.055; 0.099 | 43.57 | <0.001 |

| Type of community | 0.072 | 0.02 | 0.034; 0.110 | 12.44 | <0.001 |

| Household size | 0.035 | 0.016 | 0.004; 0.066 | 4.475 | >0.05 |

| Incomes | 0.43 | 0.025 | 0.382; 0.478 | 303.87 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dagiliūtė, R. Environmental Information: Different Sources Different Levels of Pro-Environmental Behaviours? Sustainability 2023, 15, 14773. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014773

Dagiliūtė R. Environmental Information: Different Sources Different Levels of Pro-Environmental Behaviours? Sustainability. 2023; 15(20):14773. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014773

Chicago/Turabian StyleDagiliūtė, Renata. 2023. "Environmental Information: Different Sources Different Levels of Pro-Environmental Behaviours?" Sustainability 15, no. 20: 14773. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014773

APA StyleDagiliūtė, R. (2023). Environmental Information: Different Sources Different Levels of Pro-Environmental Behaviours? Sustainability, 15(20), 14773. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014773