1. Introduction

With the continuous deterioration of the ecological environment, as well as the depletion of natural resources, the issue of environmental sustainability arises as a universal concern [

1,

2]. Although global environmental organizations, as well as national agencies, have introduced various measures to deal with the environmental crisis, enterprises are considered a major contributor to environmental problems and are thus held accountable for dealing with them [

3,

4]. As corporate environmental responsibility has taken root in most societies around the world, enterprises are bound to face more environmental demands than in the past. To date, while most firms have included an environmental component in their strategic planning and formal policies, they still largely count on their employees’ discretion and voluntary action to accomplish environmental objectives [

5]. Therefore, a model of corporate green development that features the micro-foundations of environmental sustainability within organizations, that is, their employees’ pro-environmental attitudes and behavior, is much needed [

6].

Employees’ green behavior is generally defined as the behavior taken by work professionals to minimize the negative impact on the environment or to have a positive impact on environmental protection in the workplace [

7,

8]. Discretionary in nature, this kind of behavior relies on employees’ green-related initiatives that exceed the performance expectations of the organization [

9,

10]. Accordingly, employees’ green behavior is more likely to be shaped by their immediate social environments (e.g., their leaders) rather than guided and restricted by the rules and regulations of their organizations [

11]. Prior research has examined and reported associations of employee green behavior with various leadership variables such as environmentally specific transformational leadership [

12,

13], environmental leadership [

14,

15], the leader’s own voluntary green behavior [

11,

16,

17], etc. Among these leadership variables, one that has just received recent attention is environmentally specific servant leadership, which is an extension of servant leadership into the context of green management.

Servant leadership is defined as a practice of leadership that puts the interests of others over the leader’s and focuses on their growth and development [

18]. Servant leaders undertake ethical responsibility for the success of the organization, subordinates, customers, and other stakeholders [

19]. Researchers have found that such characteristics as self-sacrifice and altruism possessed by servant leaders have an effect on the development of the green behavior of employees [

20]. With this in mind, researchers have recently further expanded the domain of servant leadership to include green values and environmental leadership practices using the label “environmentally specific servant leadership” for such a construct [

21,

22,

23]. At its core, environmentally specific servant leadership is a leadership style that aims at environmental concerns by offering subordinates green knowledge, skills, and training to help promote environmental values and activities [

24,

25,

26]. Accordingly, environmentally specific servant leaders can be an important guarantee for the enterprise’s green development [

27]. They inspire employees’ environmental behavior by acting as role models to instill environmental values; additionally, they respect the contributions of their subordinates to the environment [

24]. While researchers have reported the relationships of environmentally specific servant leadership with employee green outcomes at work [

25,

28,

29], less is known about the underlying mechanisms linking the two.

In addition, environmentally specific servant leadership is an important source of work events concerning environmental issues. According to affective event theory [

30], work events are foundational social conditions that trigger individuals’ emotional responses, which further influence their work attitudes and behavior. Previous studies on employee voluntary green behavior have mainly employed theoretical perspectives that tap into the cognitive process, such as the theory of planned behavior, social learning theory, social identity theory, and self-determination theory [

17,

24,

31]. On the other hand, less was investigated from an affective perspective, particularly on the impact of leadership on employee green behavior. One exception is studies that link passion to certain leadership styles (e.g., spiritual leadership, environmentally specific transformational leadership) [

10,

32]. However, more research is needed to unpack the affective process in which leaders shape employee green behavior.

Recognizing this research deficiency, this paper attempts to explore the affective mechanism in which environmentally specific servant leadership stimulates employee green behavior. First, extending the literature on environmentally specific servant leadership, we theorize and empirically examine a mechanism explaining how environmentally specific servant leadership influences employee green behavior from an affective perspective. In the workplace, the leader’s behavior shapes various emotional events that trigger the emotional responses of subordinates [

33] and, subsequently, their green behavior. Yet, such an emotional lens departs from the dominant theoretical approach scholars have adopted in explaining the drivers of employee green behavior [

8]. Specifically, based on affective event theory, we view environmentally specific servant leadership as an array of positive events to reveal the indirect effect of environmentally specific servant leadership on employee green behavior. Leaders as environmental servants bring positive affective experiences to employees via assisting employees to achieve environmental goals and shaping their environmental values, which in turn stimulate employee green behavior.

Affective event theory posits that individual traits play a vital boundary role in the activation, transmission, and subsequent influence of affective response [

30]. In other words, individual differences can lead to differences in the emotional process triggered by workplace events. A potential individual emotional trait that may moderate the leadership–behavior relationship is workplace anxiety [

34], which refers to feelings of tension, unease, and nervousness about work-related performance [

35]. It depends on the specific workplace context and individual differences [

36]; that is, it is an individual disposition concerned about emotions. Physical and psychological symptoms of anxiety have been reported to impair employee performance and behaviors [

36,

37]. The current study proposes workplace anxiety as an emotion-related boundary condition. Although numerous studies suggest the impacts of workplace anxiety on organizational effectiveness [

38], ethical behaviors [

39], and job performance [

40]. To our knowledge, very few examined workplace anxieties in the green management area. In this study, we propose that workplace anxiety moderates the extent to which employees respond to positive events triggered by environmentally specific servant leadership, which is another major contribution of this paper.

5. Discussion

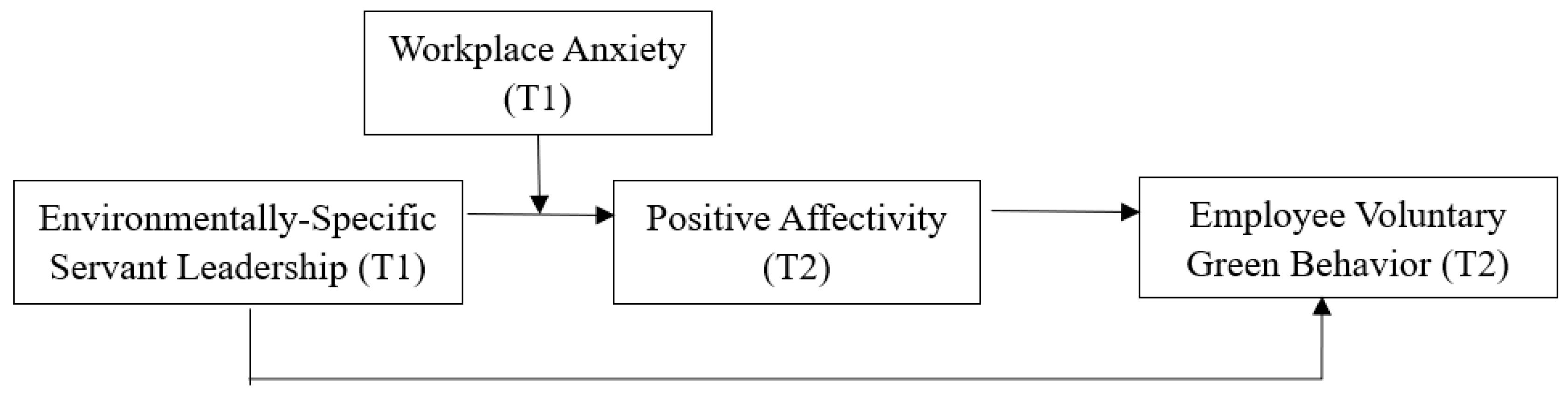

Environmental sustainability is one of the most critical topics of current society. Drawing upon affective event theory, this study developed a theoretical model explicating how environmentally specific servant leadership fosters employee voluntary green behavior. Specifically, we proposed that the relationship between environmentally specific servant leadership and employee voluntary green behavior would be mediated by employee positive affectivity, and workplace anxiety would moderate the first-stage path.

Analysis of two waves of data from 190 employees in two companies revealed that environmentally specific servant leadership directly and indirectly affected employee green behavior. Specifically, positive affectivity mediated the positive relationship between environmentally specific servant leadership and employee green behavior. Moreover, workplace anxiety moderated the relationship between environmentally specific servant leadership and employees’ positive affectivity and thus also moderated the indirect relationship between environmentally specific servant leadership and green behavior via employee positive affectivity. Employee positive affectivity mediated the indirect effects when workplace anxiety was low but not when workplace anxiety was high. In summary, these findings support the value of servant leadership in promoting employee green behavior for a more sustainable, eco-friendly workplace.

This research provided valuable theoretical insights into the extant literature in various ways. Prior research has examined an array of antecedents of employee green behavior [

8,

79], among which different types of leadership were shown to facilitate the nurturing of employee green behaviors, including environmentally specific transformational leadership [

10,

12,

13], environmental leadership [

14,

15], and ethically oriented leadership [

80,

81]. Relatively few have examined the relationship between environmentally specific servant leadership and employee green behavior. Our study adds to the literature by linking environmentally specific servant leadership with employee green behavior and reporting a positive direct effect [

12,

25,

53].

Nonetheless, the main contribution of this study is explicating the affective process in which environmentally specific servant leadership fosters employee green behavior. Norton et al. reviewed the literature on employee green behavior and identified four distinct theoretical approaches to explaining the impact of employee green behavior: (1) attitudinal, (2) normative, (3) exchange, and (4) motivational [

8]. In this study, we offered an additional emotional lens to unpack the impact of environmentally specific servant leadership on employee green behavior. From this lens, certain leader behaviors can evoke emotional responses from subordinates, which in turn influence individual behavior. Adopting affective event theory as an organizing framework, our study revealed positive affect as a link-pin between environmentally specific servant leadership and employee voluntary green behavior. We found that leaders with environmentally specific servant characteristics bring a positive affective experience to employees via assisting employees to achieve environmental goals, shaping their environmental values, and then stimulating their green behavior via this positive affectivity. These findings are consistent with and well supported by affective event theory. By conceptualizing environmentally specific servant leader behaviors as an array of workplace events that generate employees’ positive emotions, we advance the literature by introducing affective event theory into the context of green leadership and behavior in organizations.

In addition to the main effect, we also explored the moderating role of workplace anxiety. Originating from the fields of psychology and medicine, workplace anxiety is now increasingly being studied by scholars in organizational management. In fact, workplace anxiety has a significant impact on both employees and organizations. However, some of the research conducted on workplace anxiety was qualitative and from a theoretical perspective. For example, Cheng and McCarthy constructed a multi-level, multi-process model of workplace anxiety via 19 theoretical propositions that highlight the processes and conditions by which workplace anxiety may lead to diminished and facilitated performance [

39]. Among the few empirical studies, the consequences of work anxiety are mainly the focus. Research has shown that high levels of individual workplace anxiety have a negative impact on organizational effectiveness [

35], ethical behavior [

38], and job performance [

40]. According to affective event theory, individual traits serve as a boundary role in the activation, transmission, and subsequent influence of emotional response [

30]. Essentially, workplace anxiety is an emotionally relevant individual differences variable that can lead to differences in the emotional responses triggered by events [

39]. The significant effects of leadership found only with the low level of workplace anxiety point to the need to include emotionally relevant traits when seeking to understand the contextual influence on individual affect and the resulting behavior.

5.1. Practical Implications

Companies are increasingly being asked to improve their environmental performance and take on more corporate social responsibility [

8,

11]. Corresponding to this call, our research provides several managerial implications for organizations and managers to facilitate employee voluntary green behavior. Firstly, this study reinforces the importance of environmentally specific servant leadership. The findings show that environmentally specific servant behaviors by leaders can produce a positive effect on employees, which in turn leads to an increase in their voluntary green behavior. While selecting managers, preference should be given to individuals who can demonstrate environmentally specific servant behaviors. In addition, organizations can provide training and development opportunities for their managers to improve these behaviors. Environmentally specific servant leadership focuses on facilitating and nurturing the creation of green values of their subordinates [

23,

24,

25]. By engaging in positive, green-related interactions with their subordinates, these leaders can increase their subordinates’ positive emotions and green behavior.

Moreover, the fact that the instrumental value of environmentally specific servant leadership only manifests itself under the low level of workplace anxiety reveals a need to manage such a personal chronic emotional state. For instance, a meta-analysis by Martin et al. revealed that health promotion intervention in the workplace decreased employee depression and anxiety [

62]. Organizations therefore need to look after the physical health of their employees by offering various training programs. In addition, the workplace environment plays a significant role in shaping employees’ anxiety levels [

82]. Reasonable distribution of work tasks, increased autonomy at work, a healthy work climate, and other initiatives can all help to reduce workplace anxiety among employees. In doing so, organizations can leverage the full potential of environmentally specific servant leadership in promoting green behavior among employees.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although we have achieved some valuable findings, there are several limitations remaining in our study. First, we used employees’ self-reports when measuring their voluntary green behavior, which can lead to upward bias, albeit that self-report measurement is no more biased than supervisor reports [

83]. We suggested that future research collect data from multiple sources in order to obtain more reliable measures. Second, cross-sectional designs are not fully effective in providing causal inferences. We attempted to minimize this limitation by collecting data in two waves at different times. However, we recommend that scholars conduct a longitudinal investigation. Third, in addition to individual-level affective processes leading to employee green behavior, how leadership fosters green behavior via team-level affective processes and mechanisms remains a less well trodden-area that needs more research attention. As most of the work is organized and achieved by a team-based structure, we strongly encourage scholars to tackle this challenge and unpack team dynamics in the context of environmental leadership and sustainability. Additionally, our data were collected from one environmental company and one non-environmental company. There may be potential differential effects of leadership on voluntary green behavior in environmental versus non-environmental companies. Researchers could further investigate to what extent these differences are and how business contexts shape the way leaders influence the green behaviors of their subordinates. Last but not least, this study collected data from a single country—China. In order to increase the generality of our findings, future researchers could collect data from employees working in different countries, as research has shown cross-cultural differences in employees’ environmental beliefs and attitudes [

84] and voluntary green behavior [

16].