Factors Influencing Vietnamese Generation MZ’s Adoption of Metaverse Platforms

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Metarverse

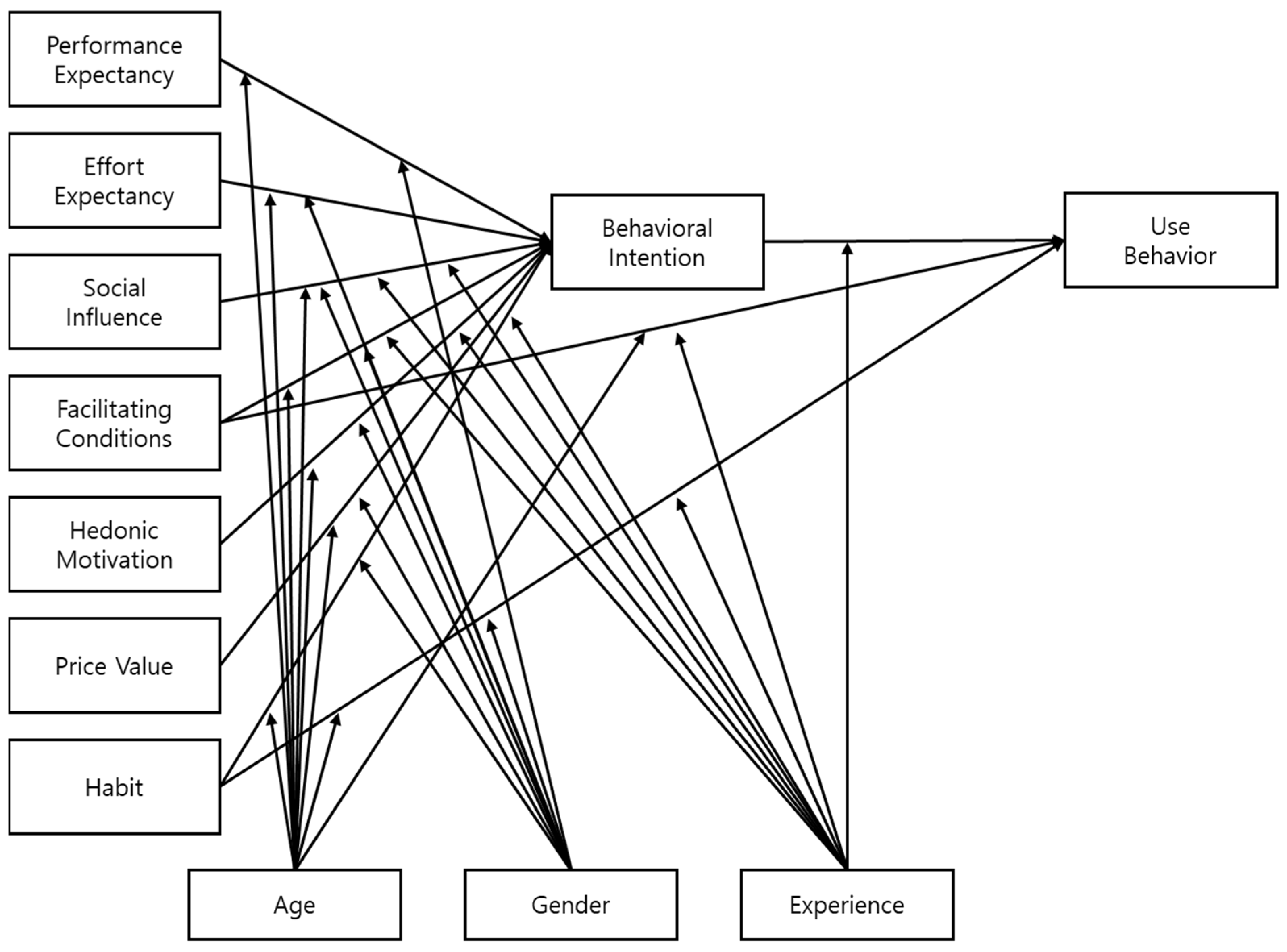

2.2. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology

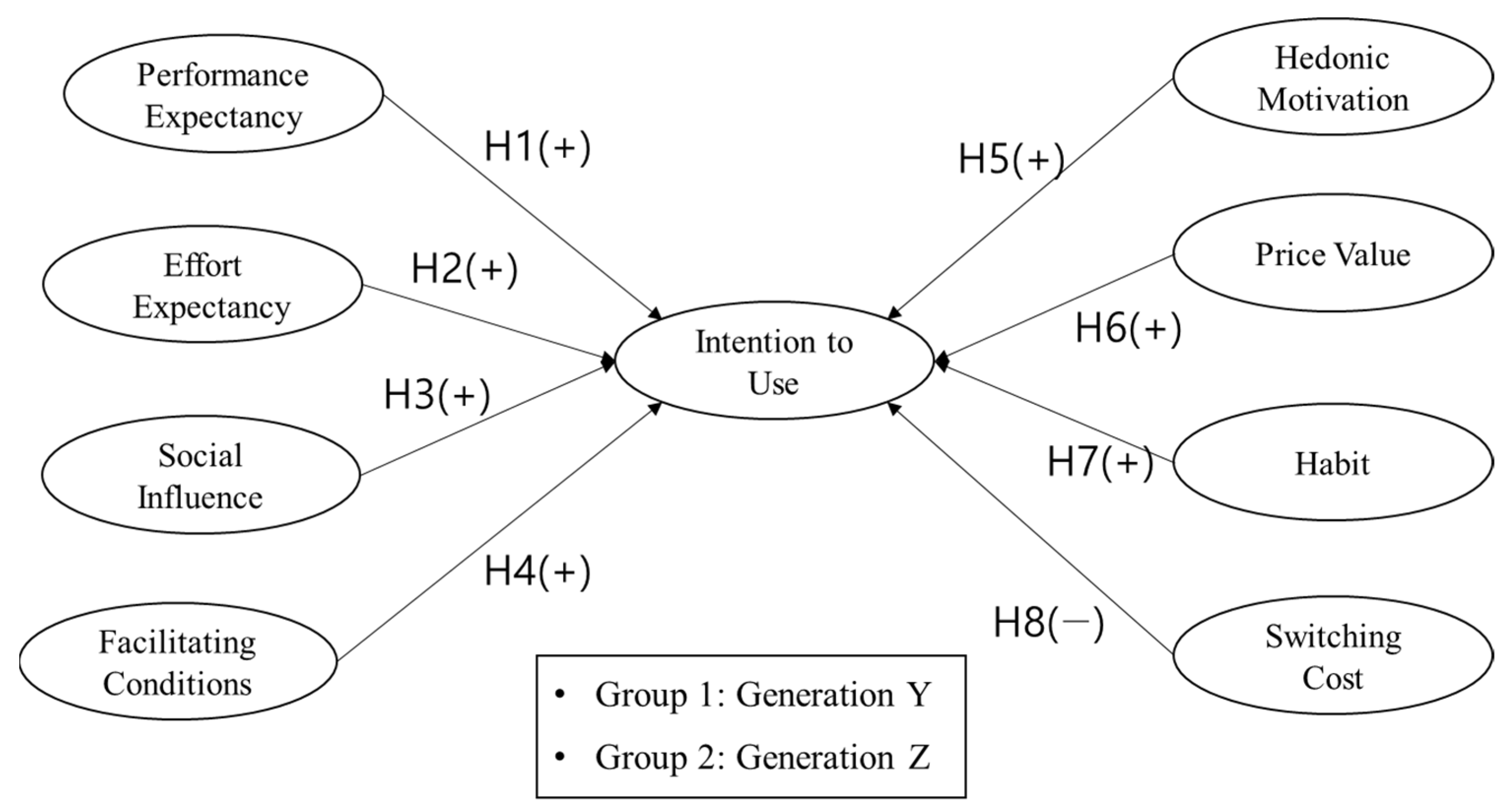

3. Hypotheses Development and Research Model

3.1. Performance Expectancy

3.2. Effort Expectancy

3.3. Social Influence

3.4. Facilitating Conditions

3.5. Hedonic Motivation

3.6. Price Value

3.7. Habit

3.8. Switching Costs

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Measurement Development

4.2. Data Collection

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Reliability and Validity Test

5.2. Structural Model

| Gen Y (230) | Gen Z (290) | t-Value for the Coefficient Difference (t > 1.96) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2/df = 1.055; GFI = 0.917 AGFI = 0.901; NFI = 0.923 CFI = 0.996; RMSEA = 0.016 | χ2/df = 1.269; GFI = 0.917 AGFI = 0.906; NFI = 0.905 CFI = 0.978; RMSEA = 0.031 | |||||||

| Path | Estimate | SE | p-Value | Estimate | SE | p-Value | tij | Result |

| PE→IU | 0.287 | 0.035 | *** | 0.219 | 0.037 | *** | 21.388 | exist |

| EE→IU | 0.121 | 0.033 | 0.007 | 0.158 | 0.045 | 0.011 | 34.538 | exist |

| SI→IU | 0.210 | 0.043 | *** | 0.088 | 0.033 | 0.152 | 36.726 | exist |

| FC→IU | 0.095 | 0.038 | 0.042 | 0.121 | 0.037 | 0.040 | −8.194 | exist |

| HM→IU | 0.186 | 0.043 | 0.001 | 0.177 | 0.032 | 0.004 | 2.744 | exist |

| PV→IU | 0.164 | 0.039 | 0.002 | 0.281 | 0.036 | *** | −35.591 | exist |

| HB→IU | 0.054 | 0.038 | 0.287 | 0.208 | 0.038 | 0.002 | −46.053 | exist |

| SC→IU | −0.314 | 0.041 | *** | −0.122 | 0.031 | 0.036 | −61.000 | exist |

6. Conclusions

6.1. Discussion of Key Findings

6.2. Academic Implications

6.3. Practical Implications

7. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Definition | Measurement Items | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Expectancy | The extent to which a person believes that using a system will enhance their job performance. | PE1 | I find Metaverse platforms useful in my daily life. | [39,47] |

| PE2 | Using Metaverse platforms helps me accomplish tasks more efficiently. | |||

| PE3 | Utilizing Metaverse platforms boosts my productivity. | |||

| Effort Expectancy | The ease of using a system | EE1 | I find it easy to learn how to use Metaverse platforms. | [39,50] |

| EE2 | My interactions with Metaverse platforms are clear and straightforward. | |||

| EE3 | I can easily master the use of Metaverse platforms. | |||

| Social Influence | The extent to which an individual feels it is important for others to think they should use the new system | SI1 | People who matter to me believe I should use Metaverse platforms. | [39,47] |

| SI2 | People who shape my decisions feel I should utilize Metaverse platforms. | |||

| SI3 | People whose views I respect suggest I engage with Metaverse platforms. | |||

| Facilitating Conditions | How much an individual thinks there is organizational and technical support for technology use | FC1 | I possess the necessary resources to utilize Metaverse platforms. | [39,47,50] |

| FC2 | I have the essential knowledge to use Metaverse platforms. | |||

| FC3 | When facing challenges with Metaverse platforms, I can seek assistance. | |||

| Hedonic Motivation | The enjoyment or satisfaction obtained from using technology | HM1 | Engaging with Metaverse platforms is intriguing. | [39,47,52] |

| HM2 | Using Metaverse platforms is pleasurable. | |||

| HM3 | Interacting with Metaverse platforms is amusing. | |||

| Price value | The mental balance between seeing technology’s benefits and its financial cost | VP1 | Metaverse platforms are priced reasonably. | [39,50] |

| VP2 | Metaverse platforms offer good value for money. | |||

| VP3 | Metaverse platforms deliver commendable value for their price. | |||

| Habit | The inclination to use a specific technology or service without realizing it | HB1 | Engaging with Metaverse platforms has become habitual for me. | [39,57] |

| HB2 | It feels natural for me to use Metaverse platforms. | |||

| HB3 | I use Metaverse platforms spontaneously, without premeditation. | |||

| Switching Cost | The financial or other costs associated with trying out a new system | SC1 | I believe there might be a monetary expense associated with using Metaverse platforms. | [67] |

| SC2 | I reckon using Metaverse platforms might consume time. | |||

| SC3 | I suspect there could be non-financial costs when using Metaverse platforms. | |||

| Intention to Use | How much a person has intentionally planned to take or avoid a specific action in the future | BI1 | I aim to conduct payments using Metaverse platforms in the future. | [39] |

| BI2 | I am inclined to consistently use Metaverse platforms in my routine. | |||

| BI3 | I have plans to utilize Metaverse platforms soon. | |||

References

- Richter, S.; Richter, A. What is novel about the Metaverse? Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 73, 102684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Hughes, L.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, S.; Giannakis, M.; Al-Debei, M.M.; Dennehy, D.; Metri, B.; Buhalis, D.; Cheung, C.M.K.; et al. Metaverse beyond the hype: Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 66, 102542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Leung, D.; Lin, M. Metaverse as a disruptive technology revolutionising tourism management and marketing. Tour. Manag. 2023, 97, 104724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, A.; Wang, R.; Stasi, A. Exploring the intersection of sustainable consumption and the Metaverse: A review of current literature and future research directions. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, M. The Metaverse: And How It Will Revolutionize Everything; Liveright Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- IntelligenceBloomberg. Metaverse May Be $800 Billion Market, Next Tech Platform. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/blog/metaverse-may-be-800-billion-market-next-tech-platform/ (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Statista.com. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1288870/reasons-joining-metaverse/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Knox, J. The metaverse, or the serious business of tech 4.0 play. New Media Soc. 2022, 24, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Maloney, D. A Youthful Metaverse: Towards Designing Safe, Equitable, and Emotionally Fulfilling Social Virtual Reality Spaces for Younger Users. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School of Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.M.; Kim, Y.G. A metaverse: Taxonomy, components, applications, and open challenges. IEEE Access 2021, 10, 4209–4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Porral, C.; Pesqueira-Sanchez, R. Generational Differences in Technology Behaviour: Comparing Millennials and Generation X. Kybernetes 2020, 49, 2755–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, B.L.; Ashford, R.D.; Magnuson, K.I.; Pettes, S.R. Comparison of Smartphone Ownership, Social Media Use, and Willingness to Use Digital Interventions Between Generation Z and Millennials in the Treatment of Substance Use: Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daqar, M.A.; Arqawi, S.; Karsh, S.A. Fintech in the Eyes of Millennials and Generation Z (the Financial Behavior and Fintech Perception). Banks Bank Syst. 2020, 15, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debb, S.M.; Schaffer, D.R.; Colson, D.G. A Reverse Digital Divide: Comparing Information Security Behaviors of Generation Y and Generation Z Adults. Int. J. Cybersecur. Intell. Cybercrime 2020, 3, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhinakaran, V.; Partheeban, P.; Ramesh, R.; Balamurali, R.; Dhanagopal, R. Behavior and Characteristic Changes of Generation Z Engineering Students. In Proceedings of the 2020 6th International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems (ICACCS), Coimbatore, India, 6–7 March 2020; pp. 1434–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hysa, B.; Karasek, A.; Zdonek, I. Social Media Usage by Different Generations as a Tool for Sustainable Tourism Marketing in Society 5.0 Idea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisenwits, T.H. Differences in Generation Y and Generation Z: Implications for Marketers. Mark. Manag. J. 2021, 31, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Shams, G.; Rehman, M.A.; Samad, S.; Oikarinen, E.-L. Exploring Customer’s Mobile Banking Experiences and Expectations among Generations X, Y and Z. J. Fin. Serv. Mark. 2020, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viet, L. “Metaverse” Trước cơ Hội Cất Cánh trong Năm 2022. Available online: https://vtv.vn/the-gioi/metaverse-truoc-co-hoi-cat-canh-trong-nam-2022-2022010617140588.htm (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Joshua, J. Information bodies: Computational anxiety in neal Stephenson’s snow crash. Interdiscip. Lit. Stud. 2017, 19, 17–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyda, M. Let’s Rename Everything “the Metaverse!”. Computer 2022, 55, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.I.D.; Bergs, Y.; Moorhouse, N. Virtual reality consumer experience escapes: Preparing for the metaverse. Virtual Real. 2022, 26, 1443–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollensen, S.; Kotler, P.; Opresnik, M.O. Metaverse—The New Marketing Universe. J. Bus. Strategy 2022, 44, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozumder, M.A.I.; Sheeraz, M.M.; Athar, A.; Aich, S.; Kim, H.C. Overview: Technology roadmap of the future trend of metaverse based on IoT, Blockchain, AI technique, and medical domain metaverse activity. In Proceedings of the 2022 24th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT), Pyeongchang, Republic of Korea, 13–16 February 2022; pp. 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner. Predicts 2022: 4 Technology Bets for Building the Digital Future. 2022. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/documents/4009206 (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Xi, N.; Chen, J.; Gama, F.; Riar, M.; Hamairi, J. The Challenges of Entering the Metaverse: An Experiment on the Effect of Extended Reality on Workload. Inf. Syst. Front. 2022, 12, 659–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, J.; Goldman, D.B.; Achar, S.; Blascovich, G.M.; Desloge, J.G.; Fortes, T.; Gomez, E.M.; Häberling, S.; Hoppe, H.; Huibers, A.; et al. Project Starline: A high-fidelity telepresence system. ACM Trans. Graph. 2021, 40, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastowka, G. User-generated content and virtual worlds. Vanderbilt J. Entertain. Technol. Law 2021, 10, 893–917. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, M.; Gupta, B.B. Metaverse technology and the current market. Natl. Inst. Technol. Kurukshetra 2021, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. Metaverse’s Characteristic Factors Affecting Word-of-Mouth Intention: Focused on Flow and Satisfaction. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School of Digital Management and e-Business, Korea University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Aburbeian, A.M.; Owda, A.Y.; Owda, M. Technology Acceptance Model Survey of the Metaverse Prospects. Artif. Intell. 2022, 1, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, E.J. The Effect of Virtual World Metaverse Experience Factors on Behavioral Intention through Presence and Satisfaction—Focused on the Generation Z Metaverse Users. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School of Media Culture Convergence, Sungkyunkwan University,, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, J.-H. A study on factors affecting the intention to use the metaverse by applying the extended technology acceptance model (ETAM): Focused on the virtual world metaverse. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2021, 21, 204–216. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, D.K. An Effect of the Untact Education and Training Using Metaverse on Trainees’ Learning Immersion. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School of Business Administration, Kyungil University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, C.S. A Study on the Factors Influencing the Perception of Metaverse Services: Focusing on Motivation to Use and Immersion. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School of Media, Kyunghee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Akour, I.A.; Al-Maroof, R.S.; Alfaisal, R.; Salloum, S.A. A Conceptual Framework for Determining Metaverse Adoption in Higher Institutions of Gulf Area: An Empirical Study Using Hybrid SEM-ANN Approach. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.K.; Kang, Y.J. A study on the intentions of early users of metaverse platforms using the technology acceptance model. J. Digit. Converg. 2021, 19, 275–285. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Eder, L.B. Intentions to Use Virtual Worlds for Education. J. Inf. Syst. Educ. 2009, 20, 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamilmani, K.; Rana, N.P.; Wamba, S.F.; Dwivedi, R. The Extended Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT2): A Systematic Literature Review and Theory Evaluation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 57, 102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutterlein, J.; Kunz, R.E.; Baier, D. Effects of lead-usership on the acceptance of media innovations: A mobile augmented reality case. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 145, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faqih, K.M.S.; Jaradat, M.I.R.M. Integrating TTF and UTAUT2 Theories to Investigate the Adoption of Augmented Reality Technology in Education: Perspective from a Developing Country. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.S.; Kang, D.Y.; Marina, S.J. Understanding Factors Influencing Usage and Purchase Intention of a VR Device: An Extension of UTAUT2. Inf. Soc. Media 2017, 18, 173–208. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, B.G.; Dong, H.L. Influential Factors on Technology Acceptance of Augmented Reality (AR). Asia Pac. J. Bus. Ventur. Entrep. 2019, 14, 153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Gharaibeh, M.K.; Gharaibeh, N.K.; Khan, M.A.; Abuain, W.A.K.; Alqudah, M.K. Intention to Use Mobile Augmented Reality in the Tourism Sector. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2021, 37, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Ren, L.; Gu, C. A study of college students’ intention to use metaverse technology for basketball learning based on UTAUT2. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S. An empirical study on the factors affecting intention to adoption of eXtended Reality. J. Digit. Contents Soc. 2021, 22, 1101–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, I.M. Predicting the acceptance and use of information and communication technology by older adults: An empirical examination of the revised UTAUT2. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 935–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, M.R.; Sanchez, P.R.P.; Martin, F.V. Eco-Friendly Performance as a Determining Factor of the Adoption of Virtual Reality Applications in National Parks. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 798, 148990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.Z.; Lee, J.H. The Comparative Study on Third Party Mobile Payment between UTAUT2 and TTF. J. Distrib. Sci. 2017, 15, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, G.; Oliveira, T.; Popovic, A. Understanding the internet banking adoption: A unified theory of acceptance and use of technology and perceived risk application. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2014, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Zhang, X. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology, US vs. China. J. Global Inform. Technol. Manag. 2010, 13, 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Correa, P.R.; Cataluna, F.J.R.; Gaitan, J.A.; Velicia, F.M. Analysing the Acceptation of Online Games in Mobile Devices: An Application of UTAUT2. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Philos. Rhetor. 1977, 10, 130–132. [Google Scholar]

- Marwell, G.; Oliver, R.L. Social networks and collective action: A theory of the critical mass. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, 502–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Lee, K.H. Multiple Routes for Social Influence: The Role of Compliance, Internalization, and Social Identity. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2002, 1, 226–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algahtani, M.; Altameem, A.; Baig, A.R. Adoption of Virtual Reality Technology in Health Centers. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Netw. Secur. 2021, 21, 219–228. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, W.; Wild, F.; Vovk, A.; Lefrere, P.; Klemke, R.; Fominykh, M.; Kuula, T. A Technology Acceptance Model for Augmented Reality and Wearable Technologies. J. Univ. Comput. Sci. 2018, 24, 192–219. [Google Scholar]

- Bower, M.; Dewitt, D.; Lai, J.W.M. Reasons Associated with Preservice Teachers’ Intention to Use Immersive Virtual Reality in Education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51, 2215–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, V.; Santini, F.O.; Araujo, C.F. A Meta-Analytic Review of Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Values. J. Consum. Market. 2018, 35, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.Q.; Park, H.J. Consumer Study on the Acceptance of VR Headsets based on the Extended TAM. J. Digit. Converg. 2018, 16, 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, G.; Oliveira, T. Understanding Mobile Banking: The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology Combined with Cultural Moderators. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulo, M.M.; Paulo, R.; Oliveira, T.; Moro, S. Understanding mobile augmented reality adoption in a consumer context. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2018, 9, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limayem, M.; Hirt, S.G.; Cheung, C.M.K. How habit limits the predictive power of intention: The case of information systems continuance. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 705–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, E.; Berger, B. Escaping Reality: Examining the Role of Presence and Escapism in User Adoption of Virtual Reality Glasses. Eur. Conf. Inf. Syst. 2017, 25, 2413–2428. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.-Y.; Hitt, L.M. Information Technology and Switching Costs. Handb. Econ. Inf. Syst. 2005, 1, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.A.; Mothersbaugh, D.L.; Beatty, S.E. Why customers stay: Measuring the underlying dimensions of service switching costs and managing their differential strategic outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 55, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.-W.; Huang, Y.-M.; Huang, S.-H.; Chen, H.-C.; Wei, C.-W. Exploring the switching intention of learners on social network-based learning platforms: A perspective of the push pull mooring model. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2019, 15, em1747. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A Partial Least Squares Latent Variable Modeling Approach for Measuring Interaction Effects: Results from a Monte Carlo Simulation Study and an Electronic-Mail Emotion/Adoption Study. Inf. Syst. J. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 263 | 50.6 |

| Female | 257 | 49.4 | |

| Age | 15~25 | 290 | 55.8 |

| 25~40 | 230 | 44.2 | |

| Occupation | Student | 205 | 39.4 |

| Officer | 183 | 35.2 | |

| Doctor | 15 | 2.9 | |

| Police | 18 | 3.5 | |

| Businessman | 39 | 7.5 | |

| Teacher | 42 | 8.1 | |

| Others | 18 | 3.5 | |

| Education | High School | 121 | 23.3 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 307 | 59 | |

| Master’s Degree | 53 | 10.2 | |

| Doctoral Degree/Higher | 21 | 4 | |

| Other | 18 | 3.5 | |

| Place | Ha Noi | 139 | 26.7 |

| HaiPhong | 93 | 17.9 | |

| Da Nang | 89 | 17.1 | |

| Ho Chi Minh City | 150 | 288 | |

| Other | 49 | 9.4 | |

| Income | <VND 500 | 262 | 50.4 |

| VND 500~1000 | 204 | 39.2 | |

| VND 1000~1500 | 25 | 4.8 | |

| Other | 29 | 5.6 | |

| Platform | Game platform | 256 | 49.2 |

| Business platform | 214 | 41.2 | |

| Video platform | 50 | 9.6 | |

| Construct | Items | Item Loadings | CR | Cronbach’s Alpha | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Expectancy (PE) | PE1 | 0.855 | 0.907 | 0.846 | 0.764 |

| PE2 | 0.818 | ||||

| PE3 | 0.818 | ||||

| Effort Expectancy (EE) | EE1 | 0.841 | 0.908 | 0.847 | 0.766 |

| EE2 | 0.816 | ||||

| EE3 | 0.805 | ||||

| Social Influence (SI) | SI1 | 0.805 | 0.904 | 0.840 | 0.757 |

| SI2 | 0.800 | ||||

| SI3 | 0.780 | ||||

| Facilitating Conditions (FC) | FC1 | 0.826 | 0.902 | 0.837 | 0.753 |

| FC2 | 0.819 | ||||

| FC3 | 0.810 | ||||

| Hedonic Motivation (HM) | HM1 | 0.816 | 0.901 | 0.835 | 0.752 |

| HM2 | 0.806 | ||||

| HM3 | 0.755 | ||||

| Price Value (VP) | VP1 | 0.774 | 0.904 | 0.841 | 0.759 |

| VP2 | 0.835 | ||||

| VP3 | 0.803 | ||||

| Switching Cost (SC) | SC1 | 0.860 | 0.892 | 0.820 | 0.734 |

| SC2 | 0.852 | ||||

| SC3 | 0.700 | ||||

| Habit (HB) | HB1 | 0.786 | 0.899 | 0.831 | 0.748 |

| HB2 | 0.772 | ||||

| HB3 | 0.821 | ||||

| Intention to Use (IU) | IU1 | 0.877 | 0.914 | 0.859 | 0.764 |

| IU2 | 0.868 | ||||

| IU3 | 0.876 |

| EE | FC | HB | HM | IU | PE | PV | SC | SI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EE | 0.875 | ||||||||

| FC | 0.310 ** | 0.868 | |||||||

| HB | 0.333 ** | 0.342 ** | 0.865 | ||||||

| HM | 0.330 ** | 0.348 ** | 0.431 ** | 0.867 | |||||

| IU | 0.527 ** | 0.478 ** | 0.562 ** | 0.593 ** | 0.882 | ||||

| PE | 0.452 ** | 0.302 ** | 0.297 ** | 0.269 ** | 0.543 ** | 0.874 | |||

| PV | 0.240 ** | 0.276 ** | 0.442 ** | 0.507 ** | 0.568 ** | 0.207 ** | 0.871 | ||

| SC | −0.294 ** | −0.305 ** | −0.458 ** | −0.349 ** | −0.503 ** | −0.183 ** | −0.377 ** | 0.864 | |

| SI | 0.363 ** | 0.447 ** | 0.357 ** | 0.405 ** | 0.542 ** | 0.362 ** | 0.405 ** | −0.349 ** | 0.870 |

| Fit Index | Recommended Value | Structural Model |

|---|---|---|

| χ2/DF | <3.00 | 1.283 |

| GFI (goodness of fit index) | ≥0.90 | 0.950 |

| CFI (comparative fit index) | ≥0.90 | 0.989 |

| NFI (normed fit index) | ≥0.90 | 0.952 |

| AGFI (adjusted goodness of fit index) | ≥0.90 | 0.934 |

| RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation) | ≤0.050 | 0.023 |

| RMR (root mean square residual) | ≤0.050 | 0.025 |

| Hypothesis | Estimate | SE | CR | p-Value | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | PE→IU | 0.294 | 0.032 | 7.332 | *** | Accepted |

| H2 | EE→IU | 0.157 | 0.033 | 4.007 | *** | Accepted |

| H3 | SI→IU | 0.063 | 0.033 | 1.460 | 0.144 | Rejected |

| H4 | FC→IU | 0.104 | 0.032 | 2.717 | 0.007 | Accepted |

| H5 | HM→IU | 0.206 | 0.032 | 4.669 | *** | Accepted |

| H6 | VP→IU | 0.232 | 0.034 | 5.252 | *** | Accepted |

| H7 | HB→IU | 0.121 | 0.033 | 2.804 | 0.005 | Accepted |

| H8 | SC→IU | -0.160 | 0.030 | −4.081 | *** | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, Y.-C.; Nguyen, M.N.; Yang, Q. Factors Influencing Vietnamese Generation MZ’s Adoption of Metaverse Platforms. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14940. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014940

Lee Y-C, Nguyen MN, Yang Q. Factors Influencing Vietnamese Generation MZ’s Adoption of Metaverse Platforms. Sustainability. 2023; 15(20):14940. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014940

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Young-Chan, Minh Ngoc Nguyen, and Qin Yang. 2023. "Factors Influencing Vietnamese Generation MZ’s Adoption of Metaverse Platforms" Sustainability 15, no. 20: 14940. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014940

APA StyleLee, Y.-C., Nguyen, M. N., & Yang, Q. (2023). Factors Influencing Vietnamese Generation MZ’s Adoption of Metaverse Platforms. Sustainability, 15(20), 14940. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014940