1. Introduction

Since the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) was issued in 2003, the international community has extensively acknowledged the significance of safeguarding ICH for sustainable development [

1]. As one of the most important categories of ICH [

2], traditional crafts have significant potential to contribute to transition and are a driving force for sustainable transformation [

3]. Therefore, current research is re-examining the nature of craft and its potential to contribute to modern production practices and the promotion of sustainability [

3]. Craft practice has played a significant role in practice-led design research, particularly the focus and the means of theoretical investigation [

4]. In China, the Plan on Revitalizing China’s Traditional Crafts [

5], released in 2017, injected momentum into the craft–design collaboration practices. Moreover, the Cultural Development Plan for the 14th Five-Year Plan Period [

6] unveiled in 2022 emphasizes strengthening the safeguarding and inheritance of ICH, aiming to improve the practical ability of ICH and further illustrating the significance of safeguarding traditional crafts for sustainable development. Although crafts are highly valued, the extant knowledge of a specific craft is commonly characterized as tacit, where a specialized skill is ingrained in individuals or the local community [

7]. In addition, the dissemination of knowledge pertaining to ICH frequently depends heavily on oral forms rather than textual statements [

8], thereby, the inherent nature of tacit knowledge frequently precludes designers from effectively utilizing it and seamlessly incorporating it into their design ideas [

9]. As highlighted by Wang et al. [

10], the presence of disparities in the level of engagement among local participants and the existence of barriers related to tacit knowledge frequently result in challenges regarding the appropriateness and sustainability of systems developed during the design phase. Therefore, within the context of present-day society, there persists a growing risk of the loss of such knowledge. To restore equilibrium, it is imperative to understand the severe ramifications resulting from unsustainable patterns in human activity and to modify interpersonal interactions accordingly [

11]. This highlights the necessity of converting this knowledge into explicit forms [

12], through the knowledge-sharing pathway.

Since then, a plethora of valuable research accomplishments have surfaced on the topic of tacit knowledge transfer in craft–design collaboration. For instance, Suib [

9] undertook research to examine the employment of design tools as boundary objects inside a design intervention framework to facilitate knowledge exchange and collaboration across two diverse domains. Aytekin [

13] enabled the transfer of tacit knowledge and experience of Mardin local crafts in collaboration by creating a digital platform through technology. One notable facet of these studies is related to the potential impact of craft–design collaboration on the sustainability of craft. However, the focus tends toward issues of a technical disposition pertaining to technological advancements [

14]. Nonetheless, digital applications do not serve as standalone solutions but, rather, contribute to the range of available technologies for manufacturers [

15]. According to Lou’s explanation [

11], the current sustainability dilemma may be mostly attributed to deficiencies in the interconnections within the subsystem. While technology solutions excel in establishing tangible links, they fall short in establishing intangible connections. To this extent, there is still a lack of consideration for developing indicators related to the structure of sharing tacit knowledge and the taxonomy of tacit knowledge for achieving sustainability in their collaborations. In recent years, in studies on the conversion of craft knowledge, tacit knowledge conversion and management have appeared as a notable trend in research on craft–design collaboration. For example, Yasuoka and Hirata [

16] developed an interactive knowledge management system specifically tailored for metal-casting artisans, which analyzed the dynamics of interaction and collaboration among the artisans within the system. Temeltas and Kaya [

17] conducted a study investigating the evaluation of artisans’ knowledge in collaborative settings in a firm. Their study analyzed the new product development processes that were enhanced by the involvement of artisans and investigated the management’s understanding of this knowledge. Similarly, in a related field, Manfredi Latilla et al. [

18] conducted a study examining the effective implementation of knowledge transfer and the significance of artisans in facilitating knowledge transfer among arts and crafts organizations, which aims to identify how artisans contribute to the organization’s competitive advantage by analyzing and discussing five longitudinal case studies. They indicated that the obtainment and retention of knowledge by artisans play a vital role in the sustainability and long-term profitability of arts and crafts organizations, thereby demonstrating the great potential of knowledge management systems to maintain tacit knowledge of the traditional craft and of its sustainability.

In China, the concept of the “culturally inclusive community of interests” [

19,

20] under the “Belt and Road” initiative [

21] has a commonality with the purpose of safeguarding ICH. Regions along the “Belt and Road” are rich in ICH resources which have great potential in building a new international order for the safeguarding of ICH. In recent years, scholars have shown considerable concerns about craft–design collaboration research. Craft practices with the support of universities and institutions have collaborative design methods in place with the aim of filling the knowledge and experience gap between academic and ICH crafts. For example, the collaborative design paradigm created by Wang et al. [

10] incorporates transdisciplinary approaches, which discovered that with this approach, there exists the possibility for local communities to create sustainable and tailored resolutions to their own local challenges. Differing from Wang et al., Ding and Ding [

22] realized the transformation of Qiandongnan traditional crafts from product-driven to problem-driven by means of collaborative design. Although the necessity of the conversion of tacit knowledge is mentioned in these works in the literature, few of the definitions of knowledge are further defined. They highlight processes more focused on the innovation of collaborative practices and have fallen short of the analysis of the tacit dimension of crafts grounded in knowledge management, in order to explore the possibility of ICH knowledge preservation and conversion for a sustainable future.

To address the current disparity, this study examines the aspects inherent in the craft–design collaboration that impacts the capacity for knowledge sharing necessary to ensure the sustainability of ICH crafts. Thus, to gain a comprehensive understanding of craft development and craft-related circumstances, this study employs semi-structured interviews to explore the tacit knowledge associated with traditional crafts and the experiences and practices of participants. The semi-structured interviews for this research were conducted from August to December 2022, in nine regions along the Belt and Road in China: Beijing, Hohhot, Nantong, Nanping, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Haikou, Dongfang, and Changshu. A qualitative research methodology is employed in this study to uncover the underlying barriers and facilitators of tacit knowledge sharing in the context of craft–design collaboration. The investigation draws upon a sample of 22 semi-structured interviews conducted with artisans (ICH inheritors) and university academics, who possess both practical experience and theoretical research backgrounds in craft–design collaboration.

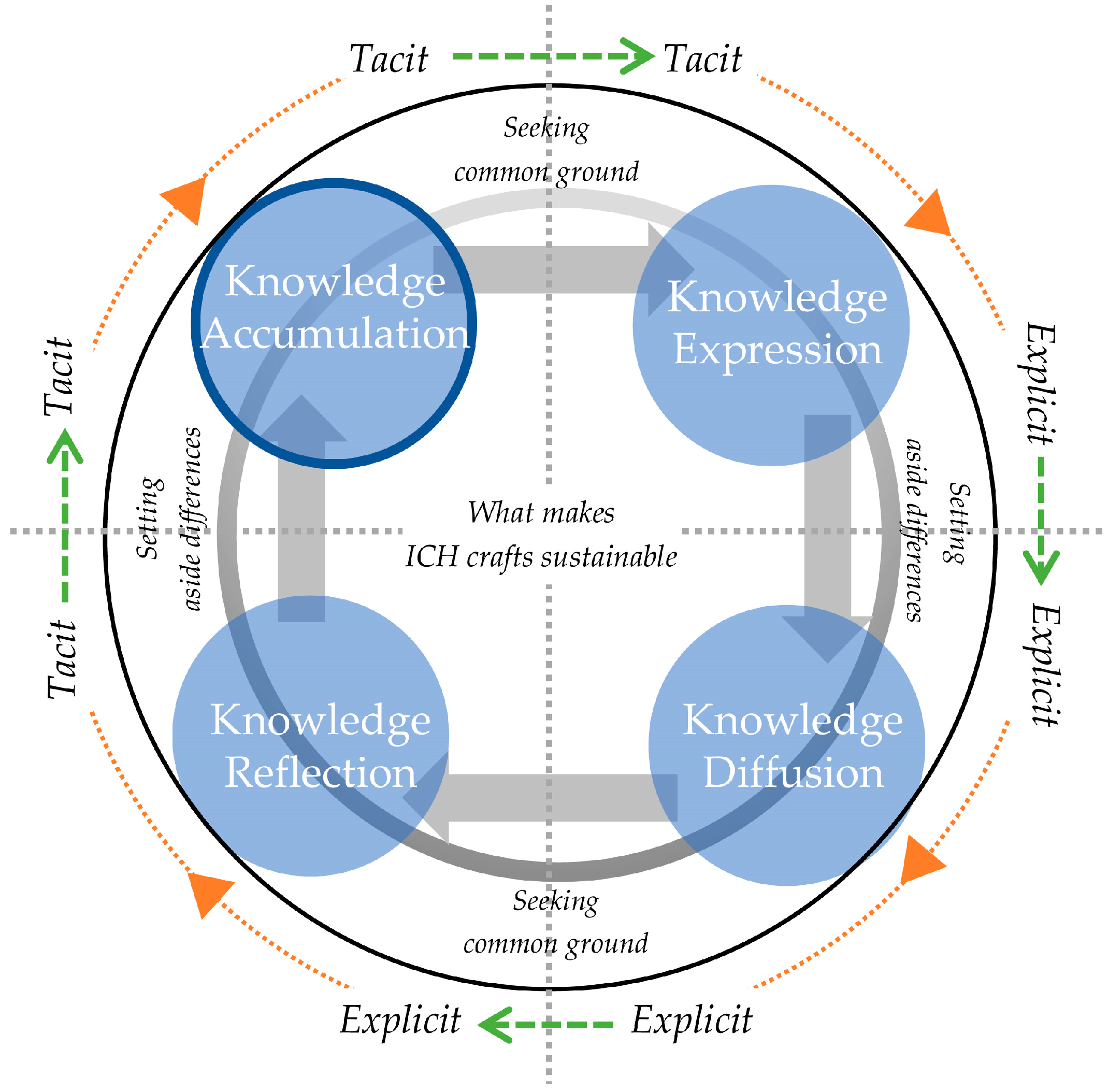

To bridge the knowledge and experience disparity between contemporary design practice and China’s ICH spheres through the formation of a knowledge structure through the mediating roles of tacit knowledge sharing, and enabling this collaboration to be a sustainable future, is the main argument in this study. By identifying “knowledge accumulation, knowledge expression, knowledge diffusion, and knowledge reflection” aspects that hinder and facilitate socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization for knowledge sharing in the stage of the fuzzy front end, idea construction, concept generation, and prototype. We advance theoretical perspectives on tacit knowledge sharing within the context of craft–design collaboration. This research endeavor enhances comprehension of the collaborative dynamics between craft and design, specifically in relation to tacit knowledge sharing. The main contribution of this study is to examine how tacit knowledge can be shared in craft–design collaboration to achieve its contribution to the sustainability of ICH craft. Additionally, we offer guidance to academics and ICH inheritors on how to foster innovation in the craft–design collaboration frameworks in the pursuit of an enhanced sustainable future.

4. Findings

Building on the notion that the “SECI and Ba” model—socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization—is most relevant for the tacit knowledge sharing in the four stages of craft–design collaboration, our analysis revealed tacit knowledge factors at levels of “knowledge accumulation“, “knowledge expression“, “knowledge diffusion“, and “knowledge reflection“ that enable the tacit knowledge sharing for the sustainability of ICH crafts in craft–design collaboration practice.

4.1. Knowledge Accumulation: Equal Access to Empirical Tacit Knowledge Assets

The challenge brought about by the collaborative development of design and ICH crafts is to see collaboration as a medium to solve unshared knowledge and unsustainable problems. Therefore, design and craft skills in collaboration should not be regarded as techniques representing different fields but as a method, applied in the process of collaboration. When the participants were asked, during the fuzzy front-end phase, how design methods and craft techniques are related within the collaborative process in order to promote the sustainable development of ICH crafts through craft–design collaboration, most of the participants’ responses focused on sharing the experience of practice and action, perceiving that this promoted the interexchange of ideas and methods from different domains and facilitated the effective change of roles and relationships in collaboration, which sustains the tacit knowledge-sharing flexibility. This was exemplified by responses from U2 and ICHI8, with U2 describing the sharing of practical experience as the second-time interpretation of ICH craft and design knowledge and a prerequisite for the sustainability of knowledge sharing at other stages, allowing the other party to accept “new” tacit knowledge while strengthening personal knowledge. ICHI8 pointed out that if the practice and action experience knowledge assets of ICH craft and design always exist on two parallel lines, then the collaborative process is difficult to sustain. Hence, the process of socialization, which involves the converting of tacit knowledge into novel tacit knowledge, may be achieved through the sharing of practical experiences and actions. With this regard, the point of the fuzzy front end is to acquire tacit knowledge essential to the craft through practical involvement, as opposed to relying solely on written manuals or textbooks.

In the collaborative process of craft design, the knowledge producers of both the university team and the ICH inheritors are the “leaders” of individual knowledge, promoting the sharing of tacit knowledge in the interaction. However, when a knowledge assets differential exists in the process of collaboration, the participants on both sides cannot communicate and interact equally, which not only hinders the interpretations of tacit knowledge of craft techniques by university team members but also hinders the ICH inheritors from accessing the design information (ICHI11). Therefore, providing equal access to each other’s empirical knowledge in craft–design collaboration is the key to the fuzzy front end. University team members and inheritors should realize that the timing of each other’s tacit knowledge is accumulated and how knowledge in unknown fields can be obtained most efficiently. Respondent U11 said that at the fuzzy front-end stage, on-site visits or seminars are used to ensure that every participant has equal access to craft and design knowledge, which makes the different perspectives from both fields serve as a basis for the exchange of tacit knowledge between different fields. In addition, respondent U4 indicated that this equal access to knowledge exists not only between ICH crafts and design disciplines but also between different types of ICH crafts. Specifically, while inheritors are teaching technical knowledge to the university team, representative inheritors of different craft categories are also making some innovations through mutual learning (U4). For example, since there are different embroidery ICH crafts in the same ethnic minority area along the Belt and Road, the mutual absorption and combination of embroidery in different regions becomes a new sustainable way of producing ICH crafts.

The fuzzy front end can be defined as the stage where experiences, feelings, and emotions are shared between participants through individual and face-to-face interactions, which primarily facilitates the socialization of tacit knowledge, considering that a face-to-face encounter is the sole means of encompassing the full range of physical emotions and responses, which are theorized to constitute crucial components in the exchange of tacit knowledge. Therefore, these responses suggest that empathy is an ability that participants possess in the process of knowledge accumulation. This was epitomized by ICHI8′s response, which indicated that the ability to empathize has broken the boundary of knowledge sharing between ICH crafts and design fields and made participants brave enough to try to learn and combine design perspectives to think about inheriting ICH crafts. Similarly, U10 responded that in craft–design collaboration projects, “even a change of perception occurs” through empathy, which becomes the basis for sharing tacit knowledge with ICH inheritors. In addition, some of the interviewees were aligned in answering that it is crucial to share skills and expertise that are gained and accumulated through practical experiences in the workplace. This sharing contributes to the formation of their own empirical tacit knowledge assets. The tacit and difficult-to-grasp characteristics of empirical tacit knowledge assets pertain to the traditions of the ICH craft itself and the longstanding pedagogical traditions and practices of specific design disciplines (U9). Therefore, this further shows that the procedure of tacit knowledge sharing is crucial to “accumulate” tacit knowledge, and that “collaboration” consists of equality, mutual benefit, and positivity. Nonetheless, since the tacit knowledge to be shared is related to the manual skills and abilities of the inheritors, this makes the experiential knowledge assets a unique and difficult-to-imitate resource for university-based craft–design collaboration (U8). Thus, this indicates the exclusivity of shared empirical knowledge assets in collaboration, which provides a sustainable competitive advantage for the development of ICH crafts (ICHI1).

The process of knowledge accumulation entails the collective acquisition of tacit knowledge, which is cultivated through the exchange of experiential knowledge among individuals of both university academics and ICH inheritors. The skills and knowledge accumulated by ICH inheritors through craft work experience are proper interpretations for experiential knowledge assets. The fuzzy front end allows university groups to understand the expertise of craftsmanship through practical demonstrations conducted by an ICH inheritor. However, the sharing of such empirical tacit knowledge assets occurs both intentionally and inadvertently. Therefore, in some cases, participants may be uncertain about the integrity of the sharing. In this sense, more research is needed to determine how fuzzy front ends, in collaboration, build the integrity of knowledge accumulation.

4.2. Knowledge Expression: Knowledge Vision in Craft–Design Collaboration

In the context of knowledge expression, externalization refers to the act of transforming tacit knowledge that exists in the craft–design collaboration into an explicit form. In this stage, the synthesis of the tacit knowledge of the university team and ICH inheritors makes the knowledge explicit and incorporates it into novel ideas and innovative ICH craft designs. Therefore, as shown by U8, the preservation, and sharing of their tacit knowledge assets represents a way in which their vision of craft–design collaboration (including the concept of a knowledge vision) provides guidance for the process of sharing knowledge and the resulting knowledge that is generated. When the tacit knowledge of the inheritor is made explicit during the design idea exchange in a collaboration project, thereby allowing it to be shared by the university team and ICH inheritors in collaboration, the knowledge becomes the basis of new knowledge of the innovative ICH craft product (U10). Similarly, U11 described how, in the design project, the university team controls whether a certain part of the outcomes of the entire collaborative project can be “replaced and improved” by modern technology based on the tacit design experience accumulated in design teaching, for years, to promote the inheritance and sustainability of ICH crafts. In addition, participant U10 said that during the stage of inspiration creation, they collaborated to use traditional inheritance as the design direction and functional design results as the vision. In other words, idea generation in craft–design collaboration was the proper interpretation for this sharing process. Moreover, a common viewpoint raised by many of the participants was that in the process of externalizing tacit knowledge, metaphors can effectively create concepts from a large amount of tacit knowledge. ICHI8 believes that communication and dialogue are very important links when collaborating with the design ideas of the university team. In the discussion of “whether the design can be put into production”, they usually use metaphors, such as craft skill language, to carry out predictive design as well as necessary experiments. U4 remarked that when learning and communicating with the inheritors, the inheritors often use symbolic language to teach some embroidery techniques. In this sense, the effective sharing and transfer of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge relies on the utilization of metaphorical language. Therefore, during collaboration, the university team and the ICH inheritors should carefully decide which “kind of language” to use to explain and share their individual knowledge reasonably, according to the purpose of the entire project (U10). U10 also indicated that in collaboration, participants are encouraged to build their own pool of design inspirations and express them in their own way, so that they can effectively use their respective design languages. For example, when promoting the creativity of ICH design, the collaborative team integrates and summarizes the design thinking and ICH craft thinking perspectives of different participants and uses metaphors in the dialogue to create ideas for design inspiration.

During idea construction, collective and face-to-face interactions are the main content of the activities. More specifically, U1 indicated that this is the stage where the university groups and ICH inheritors’ skills and thinking models are converted into common terms and then articulated as new ICH craft design ideas. This expression of new ICH craft design idea knowledge represents the vision of the collaboration for the overall goals of the projects (U4). Therefore, idea construction mainly offers an interactive context for the externalization of tacit knowledge. Meanwhile, ICHI3 similarly described how the modern design idea and traditional craft idea are mutually shared and expressed through iterative dialogue among participants, which forms the knowledge vision in craft–design collaboration. Here, the articulated knowledge of different domains is also projected back to each participant and subsequently internalized through self-reflection. Then, the tacit knowledge is converted into explicit knowledge by the act of sharing (U2). To this extent, the idea construction stage is consciously constructed, and most respondents agree that the most significant contributions are made at this stage, “laying the vision” (ICHI10) for the subsequent concept generation and prototyping. Hence, as U9 indicated, selecting participants with a suitable collaboration of specialized knowledge and capabilities is a crucial factor in sharing tacit knowledge in idea construction.

The explicit knowledge expressed through ICH craft language, design images, and design symbols in craft–design collaboration are the professional knowledge assets (U2) individually held by university team members and ICH inheritors, which is the knowledge expression that occurs in the stage of idea creation. In this sense, the ICH inheritors and university teams have the autonomy to select the recipients of their specialized knowledge and abilities during collaborative efforts (ICHI3). This decision-making process is, to some extent, based on their knowledge vision. “Product designs, brand concepts, and the traditional implications” (ICHI8) of ICH crafts are proper interpretations for conceptual knowledge assets. The expression and comprehension of conceptual knowledge assets in idea production are comparatively more straightforward, due to their concrete nature, in contrast to the experience knowledge assets that exist in the fuzzy front-end stage. Therefore, the knowledge can be transferred from tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge and put into the next stage of collaboration.

To facilitate the ongoing and interactive sharing of knowledge, it is imperative to possess a comprehensive vision that effectively aligns all the stages of craft–design collaboration. Since knowledge expression is unlimited in craft–design collaboration, the knowledge vision of collaboration must be redefined according to the knowledge possessed by the university teams and inheritors who participated in the relevant projects, rather than using existing definitions of fixed technology models and products. Furthermore, metaphors play a key role in the definition of knowledge visions. The knowledge vision specifies what type of new ICH product the collaboration with the design domain should produce. In short, it determines how the craft–design collaboration evolves over the long term. Hence, it is crucial to create a comprehensive knowledge vision that surpasses the limitations imposed by current ICH crafts, design disciplines, enterprises, and markets.

4.3. Knowledge Diffusion: Knowledge Missions as a Sustainability Intermediary

The concept generation stage involves the converting of ICH crafts’ explicit knowledge shared from the previous stage into a more structured collection of explicit knowledge, promoting the sustainability of ICH crafts in modern times. The acquisition of explicit knowledge occurs through internal collaboration, whereby it is then amalgamated and refined to provide design sketches that reflect the anticipated results of the newly acquired knowledge. The combination of novel explicit knowledge is thereafter shared among the participants involved in the collaboration. The design sketches new knowledge since it amalgamates knowledge from diverse sources within a collaborative framework. Notably, the creative use of modern technology and intelligent software assistance can facilitate this mode of knowledge diffusion (U11). In addition, the process of knowledge dissemination includes the act of decomposing design concepts, wherein a notion such as knowledge vision is broken down into operationalized ICH product concepts (U6). This decomposition not only enables the creation of explicit knowledge but also contributes to the development of a systemic understanding (ICHI4). Therefore, knowledge acquisition and integration in collaboration are the basis for knowledge diffusion. The university groups and ICH inheritors are engaged in implementations of the iteration of conceptual design sketches, by gathering craft skills and material information, as well as managing the concept sketches to transmit newly created concepts as knowledge missions for sustainability intermediaries. This was epitomized by U2′s response, who considered that from the perspective of university students, although a few weeks is far from enough for one to understand ICH crafts, the advantage students hold is, that they have the ability to “understand culture” and “master knowledge”, as well as the ability to “quickly absorb and imagine and create”, which are very “necessary and fundamental” to inheritance and innovation of ICH crafts. ICHI8, similarly, described that since the university students who collaborate each year hold different design thinking processes and are good at “making use of what they have learned or new design information they have received”, this makes ICH crafts more in line with the sustainability of contemporary times. However, the interviewee mentioned that the cultural survey, in the form of a questionnaire conducted before the collaborative design project, showed that 95% of the young participants were resistant to ICH (U2). This shows that the popularization of ICH craft knowledge among the younger generation should become the focus of collaborative design between universities and inheritors to achieve intergenerational equity in cultural inheritance. In addition, “age reduction” has become one of the main purposes of the concept generation stage in craft–design collaboration, which makes young people understand ICH crafts, thereby continuing sustainably. For example, cultural creative products and Chinese chic (guochao) products are means of “age reduction” in ICH craft design products, aiming to attract the attention of a young audience (ICHI8).

The process of knowledge diffusion primarily provides a context for integrating pre-existing explicit knowledge within the domains of design and craft. This type of explicit knowledge may be relatively readily shared across individuals through the medium of sketching. Even under time and space constraints or some unexpected uncontrollable situations, knowledge diffusion, because it is easy to transfer, can smoothly interact with collaborative teams through a virtual network environment, such as online video conferencing, through which university groups and ICH inheritors can exchange design knowledge or reply to each other’s questions to efficiently acquire and diffuse design and craft concepts. U10 elaborated that the design cases were shown to the inheritors through video conferences, and further discussed with each other how to design innovative ICH craft products; for example, which parts of the outcome can be completed independently with (name of the ICH craft) techniques, which parts of craft techniques can be improved, and which parts can be combined with design. The inheritors show interest and actively respond through interaction in the virtual space—“breaking traditional interaction methods” (ICHI5) makes collaboration more possible. Meanwhile, under uncontrollable circumstances, this can smoothly promote contemporary progress in the ICH craft market.

The knowledge in knowledge diffusion consists of systematized design synergy and structured and formalized explicit knowledge, such as clearly stated craft skills of ICH crafts, the expected scale of innovative ICH craft specifications, design sketches, and information about modern design tools that can be improved. A unique characteristic of this stage is that the knowledge of either ICH craft or design can be shared and transferred relatively easily since they were screened and combined. This particular form of knowledge asset holds a high level of tangibility within the context of collaborative sharing processes. By this stage, the collaborative relationship tends to mature, and the shareability of knowledge has reached a new threshold value. Hence, the “knowledge diffusion” is seen as a mission to achieve the knowledge vision; thereby, shared knowledge is combined to achieve the goal of being a sustainability intermediary.

4.4. Knowledge Reflection: Understanding the Sustainability of Individual Differences

The craft–design collaboration is continually evolving to meet the contemporary social needs of ICH crafts and the knowledge interaction as part of collaborative multidisciplinary teams, improving the possibility of the modernization of ICH crafts. However, at the same time, the convergence of knowledge in different fields has the risk of superficial retention, which leads to the inability of design results to penetrate deep into the cultural core (U2). Therefore, in collaboration, reflection on individual differences in the inheritance of ICH crafts is a significant factor in promoting sustainability. Rather than saying that the technique of ICH is documentary, U2 considered its core to be narrational. Therefore, the innovation of ICH crafts is to understand the narrative style of its core values rather than just to add certain elements. Core values can be about individual differences that represent spirit, technology, and experience. Only on this basis can participants create innovations that belong to this craft (ICHI2). Hence, if tacit knowledge, as the core value of culture, is to be shared and spread, the beginning and end of the knowledge sharing process must complement each other. For example, the interviewees mentioned that in the inheritance and innovation of (name of ICH craft) skills, whether in terms of skills or core value inheritance, there is a story structure; that is, the content described in each craft work contains the characteristics of (name of city), as well as some of the most important concepts in indigenous culture (U2). Therefore, in the process of collaboration and the sharing of tacit knowledge of ICH crafts, whether from the content level or the technical level, the cultural core expressed by the individual differences in the ICH crafts itself runs through as a central axis, which plays a key role responsible for of the overall trend of craft–design collaboration. Similarly, as a huge system of ICH, to play the role of boosting cultural inheritance under the craft–design collaboration, it is important to make the collaborative process have the same “entrance” but to encourage different “exits” (U2). Different “exits” refer to finding an appropriate angle to innovate in the context of multi-disciplinary intervention in the process of craft–design collaboration, combined with individual differences in thinking and experience through reflection.

Knowledge reflection encompasses the cognitive procedure of assimilating explicit knowledge and transforming it into tacit knowledge. This process involves the internalization of newly acquired knowledge derived through prototyping, thereby integrating it into the participants’ existing knowledge base. The process of knowledge reflection facilitates the dissemination of explicit knowledge within a collaborative group, enabling members to internalize and convert it into tacit knowledge. Explicit knowledge, such as the design and production techniques of ICH crafts, must be achieved through practical application (ICHI6). For instance, prototyping can help the explicit knowledge to be shared. Furthermore, the reflection of prototyping enables participants to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the details associated with the outcome. Through the process of reflection, participants can internalize the explicit knowledge that is embodied by these archetypes, therefore, enhancing their tacit knowledge repository. During the craft–design collaboration, there is a beneficial acquisition of individual-level knowledge for both university team members and inheritors. This knowledge is gained through the internalization and incorporation of knowledge into one’s tacit knowledge repositories, namely, in the context of shared technical knowledge. Further, the accumulation of tacit knowledge, on the individual level, has the potential to catalyze a subsequent phase of knowledge sharing in craft–design collaboration when it is shared with others through the stage of knowledge accumulation (U3). This shows that knowledge sharing does not just take place in a certain collaborative project but is a sustainable process of continuous updating and advancement.

Either the university groups or ICH inheritors internalize new values and ideas that are shared, understanding knowledge value through interaction with others in the collaboration. In addition, they play a crucial role in enabling the process of prototyping, fostering a challenging spirit within the collaborative, and disseminating outcomes to the entire department. The process of achievement sharing not only represents the reflection process of the knowledge exporter but also represents the reflection process of the knowledge receiver, mainly offering a context for tacit knowledge internalization, which is a reflection through action (U7). Individual differences manifested in this process comprise tacit knowledge that is embedded in the collaborative process’ routine actions and practices. ICH craft culture, craftsmanship, and the craft-making routine are the proper interpretations of individual differences. Therefore, by engaging in iterative prototype activities, certain cognitive and behavioral patterns pertaining to the creation of pertinent craft design outputs are strengthened and shared among participants in collaborative settings. In addition, the different thinking and cognition of different participants on the same topic also embody individual differences in collaboration (ICHI7). Therefore, storytelling and sharing the background of the relevant ICH crafts and design works also help participants to reflect and internalize knowledge. When the knowledge of individual differences is internalized into individual tacit knowledge through sharing, it shows that the sustainability of contemporary ICH craft design is effectively promoted (ICHI9). Through continuous exploration and experimental breakthroughs in the collaborative innovation of inheritors in the system environment of universities, the invisible knowledge-sharing behavior of individual differences in different fields becomes a mutually inspiring relationship of balanced development (U5). Therefore, from the perspective of inheritors, the key point is to keep the core cultural knowledge system of ICH, while from the point of view of universities, the focus is on integrating and innovating knowledge of functional forms, material forms, and value forms under the influence of experiments, science, and technology. On this basis, both parties must adhere to the constraints of both parties on their own positioning to achieve the goal of sustainable ICH.

5. Discussion

Sustainability interventions in design activity are a double-edged sword: both an opportunity and a challenge. These interventions facilitate a deeper understanding of the methodologies and tools utilized by practitioners in order to create and enhance initiatives and shed light on the potential of practice-oriented design to expand the reach of sustainability interventions [

82]. However, the unshared knowledge constitutes a challenge for researchers and practitioners in moving toward sustainability. Therefore, it is appropriate for knowledge sharing to be framed as promoting the sustainability of ICH crafts in craft–design collaboration. This research highlights the significance of the knowledge-sharing mode in effectively enhancing the sustainability of ICH crafts using university-based craft–design collaboration. The participants in craft–design collaboration create ICH craft products by interacting with individual knowledge and different understandings of design and craft skills. Based upon the “SECI and Ba” model of knowledge conversion derived from Nonaka and four identified stages of craft–design collaboration, we collected data during the interviews to obtain a deeper understanding of how practitioners share the tacit knowledge that exists in the process of collaboration and how they felt the craft–design collaboration contributed to the sustainability of ICH crafts according to these parameters. The data suggested that the contributions to the sustainability of ICH inheritors and university team members in craft–design collaboration are both complex and regular. They interact in a relationship of “seeking common ground while setting aside differences” in a spiral of knowledge sharing (

Figure 4).

Table 3 presents a concise overview of the main challenges in accomplishing the sustainability of ICH crafts through knowledge sharing and the changes required to improve the sustainability of ICH crafts. According to these findings, it is possible, on one hand, to perceive craft–design collaboration when knowledge is not fully shared as a collaboration process with differences in knowledge assets, isolation, and poor knowledge depth. On the other hand, to perceive craft–design collaboration when knowledge is shared as collaboration that relinquishes these concepts in favor of providing equal access, enhancing empathy, the use of metaphor language, “age reduction” design, and inclusivity of individual differences in design towards a sustainable future of ICH crafts. However, since sustaining the core of traditional skill and culture in craft–design collaboration is crucial to ICH crafts, the intervention of excessive modern knowledge in the process of ICH craft design could potentially jeopardize the core value of ICH craft inheritance. If university-based craft–design collaborative works are to manage the changes required in collaborative relationships to ensure the future survival and active inheritance of ICH crafts, in addition to their commitment to preserving the core cultural knowledge values of ICH, the collaborative strategies need to acknowledge the tensions between traditional cultures and modern design.

Knowledge sharing is a crucial aspect of knowledge management that involves the dissemination of information and specialized knowledge, with the aim of generating and using knowledge to facilitate the achievement of organizational objectives [

83]. In this study, the conceptual model of “SECI and Ba” (

Figure 2) was adapted from Nonaka et al. [

48]. This model is particularly relevant to understanding the tacit and explicit knowledge sharing tensions that exist in craft–design collaboration. The processes of “socialization to externalization” and “combination to internalization” modes of knowledge conversion closely resemble the “seeking common ground” of craft–design collaboration, while the processes of “externalization to combination” and “internalization to socialization” modes of knowledge conversion closely resemble “setting aside differences” of craft–design collaboration. The comparison of the relationship between the principle of tacit knowledge sharing in craft–design collaboration and knowledge conversion (SECI and Ba) is shown in

Table 4. However, a correlation exists between the sustainability of ICH crafts and knowledge sharing but it is not conspicuous for all stages. This may have caused confusion in the overall rhythm of collaboration and is also reflected in concerns about the one-sided interpretation of knowledge sharing in craft–design collaboration and the differential in knowledge assets. In addition, although the design results of craft–design collaboration are positioned as a medium for knowledge exchange, the capacity of research outcomes that promote breakthroughs in traditional craft manufacturing processes is, however, inhibited by the unsustainable conceptual connection between design and craft skills, as well as the problem of knowledge depth in design results.

Therefore, based on the above characteristics that are considered to make the development of ICH crafts unsustainable in craft–design collaboration, this study points out that to become sustainable, craft–design collaboration needs to adopt knowledge sharing that provides equal access and enhances empathy in knowledge accumulation, uses metaphor language in knowledge expression, realizes “age reduction” design in knowledge diffusion, and is inclusive of individual differences in design in knowledge reflection. To the extent that university teams and ICH inheritors know that they have the knowledge needed for the design goals corresponding to the various phases of knowledge sharing when they interact during this process, and to provide an opportunity to establish a more direct connection between the internal knowledge of university-based craft–design collaboration and its potential contribution to the sustainability of ICH crafts, this will reduce the uncertainty of craft–design collaboration and empower the participants’ capabilities to analyze and synthesize knowledge.

On this basis, the K-AEDR model in

Figure 5 is proposed. This model is a process of tacit knowledge sharing through the craft–design collaboration approach between university teams and ICH inheritors to promote the sustainability of ICH crafts. The knowledge shared during the interaction is dependent upon four forms of knowledge conversion: knowledge accumulation, knowledge expression, knowledge diffusion, and knowledge reflection. Each mode of knowledge sharing requires different motivations and core content to create and convert knowledge effectively. This highlights the significance of interactivity within the craft–design collaboration process in facilitating the systematization of knowledge sharing and promoting the theoretical robustness of knowledge sharing for sustainability, during the spiral process of knowledge sharing. To facilitate successful knowledge sharing and conversion, it is imperative to recognize that each modality of knowledge sharing necessitates a different objective. For example, equal access to empirical tacit knowledge assets is essential in the knowledge accumulation process for both university teams and ICH inheritors, as interpretation and access to tacit knowledge are hampered by differences in knowledge associated with the craft traditions or knowledge taught in design disciplines. In knowledge expression, a comprehensive vision that aligns the various stages of craft–design collaboration, plays a vital role in facilitating the dynamic and ongoing sharing of knowledge. Specifically, the vision of craft–design collaboration emphasizes the preservation and sharing of tacit knowledge, by doing so, it provides a clear direction for both knowledge sharing and creation. In knowledge diffusion, the knowledge of either ICH craft or design can be shared and transferred relatively easily since they are screened and combined, which is seen as a mission to achieve the knowledge vision; thereby, shared knowledge is combined to achieve the goal of being a sustainability intermediary. In knowledge reflection, participants internalize the explicit knowledge represented by the archetypes, enriching their tacit knowledge base through reflection. Understanding the sustainability of individual differences in tacit knowledge, which is accumulated at the individual level, has the potential to spark a new knowledge-sharing spiral in craft–design collaboration. By providing an explanatory framework, knowledge management theory serves an essential role in the process of craft–design collaboration. This framework enables a reorientation of craft–design collaboration towards a knowledge-sharing relationship, thereby contributing to the promotion of sustainable development in the realm of ICH crafts. In other words, the knowledge-sharing model offers practical tools and methodologies for exploring, creating, and designing to transform strategies to facilitate the adaptation of the ICH craft to the needs of modern society. The K-AEDR model offers a framework tool for evaluating the delicate balance between conflicting priorities in a sustainable manner. It not only guarantees the sustainable viability of ICH crafts but also ensures their effective contribution to the overall sustainability of the craft design ecosystem.

6. Conclusions

This study examined how craft–design collaboration manages the tacit knowledge sharing process, defined by interactions between the collaborative participants (university teams and ICH inheritors), as well as between the collaborative members and ICH crafts. It has significantly developed a notable advancement in comprehending the intricate dynamics that exist between knowledge sharing in craft–design collaboration and ICH sustainability by drawing on the knowledge management framework to construct a conceptual model for facilitating tacit knowledge sharing in craft–design collaboration. This model serves to enhance the sustainability of the preservation of ICH crafts, ensures the efficient management of internal knowledge of craft–design collaboration, and demonstrates commitment toward achieving ICH sustainability goals. Hence, in domains where knowledge sharing facilitates the advancement of craft–design collaboration, the present study identifies four primary aspects in which tacit knowledge sharing occurs during collaborations. The first form is knowledge accumulation: equal access to empirical tacit knowledge assets; the second form is knowledge expression: knowledge vision in craft–design collaboration; the third form is knowledge diffusion: knowledge mission as a sustainability intermediary; and the fourth form is knowledge reflection: understanding the sustainability of individual differences. The model argues that knowledge-sharing capability should be considered an indispensable future skill for the university academics and ICH inheritors, in terms of identifying, delineating, and solving challenges in university-based craft–design collaboration for the sustainability of ICH crafts.

The main contribution of this article is, firstly, this study brings significant new insights to the craft–design collaboration for the sustainability conversations of ICH crafts, namely how to consider individual knowledge interactions to facilitate dynamic knowledge sharing at all stages of craft–design collaboration; secondly, through data analysis, a deep understanding of the current craft–design collaboration development in regions along the Belt and Road is gained, additionally defining the tacit knowledge-sharing model of university-based craft–design collaboration; thirdly, the craft–design collaboration serves as a knowledge-sharing relationship, which ensures that the craft design eco-system towards more sustainable ends.

However, due to the limitations of the analytical sample range, it might not allow generalizing the findings to a wider range of regions. Therefore, we invite future research into this subject to connect with the external environment, enlarging and differentiating the research sample, in order to obtain a more comprehensive view of the dynamic development of the knowledge interaction between the university academics and the ICH inheritors, thus build a bridge for the sustainable iteration of new knowledge. This would help build awareness of the potential of craft–design collaboration on achieving the synergy and integration of functions and resource advantages, making intergenerational interaction of knowledge sharing possible.