Microplastics in Sandy Beaches of Puerto Vallarta in the Pacific Coast of Mexico

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

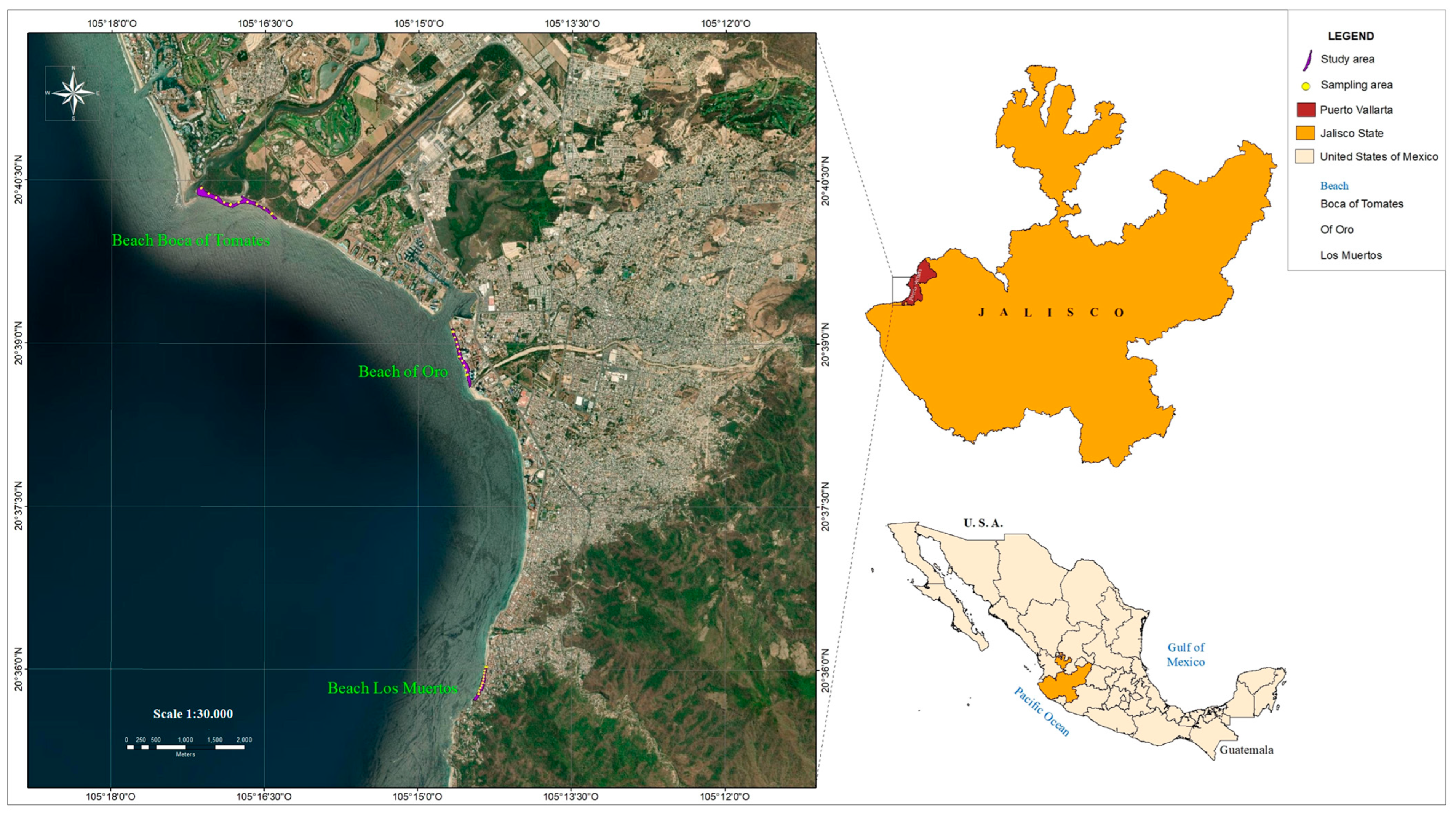

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Coastal Sand Sampling

2.3. Sample Preparation

2.4. Visual Identification and Cuantification of Microplastic

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

2.6. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

3. Results

3.1. Microplastics Present in Sediment Samples Based on Their Physical Attributes

3.2. Chemical Identification of the Types of Microplastics Present in Sand Samples

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Plastics—The Facts 2020 an Analysis of European Plastics Production, Demand and Waste Data. Available online: https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-facts-2020/ (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Van Sebille, E.; Wilcox, C.; Lebreton, L.; Maximenko, N.; Hardesty, B.D.; Van Franeker, J.A.; Eriksen, M.; Siegel, D.; Galgani, F.; Law, K.L. A global inventory of small floating plastic debris. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 124006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, L.C.M.; Van Der Zwet, J.; Damsteeg, J.W.; Slat, B.; Andrady, A.; Reisser, J. River plastic emissions to the world’s oceans. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarski, B.; Budak, I.; Micunovic, M.I.; Vukelic, D. Life cycle assessment of injection moulding tools and multicomponent plastic cap production. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 413, 137450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, A.; Liu, W.; Ali, N.; Shi, R.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Yin, C.; Liu, J.; Yu, M.; et al. Microplastic pollution in terrestrial ecosystems: Global implications and sustainable solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 461, 132636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, F.; Fossi, C.; Weber, R.; Santillo, D.; Sousa, J.; Ingram, I.; Nadal, A.; Romano, D. Marine litter plastics and microplastics and their toxic chemicals components: The need for urgent preventive measures. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2018, 30, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, A.A. The Physical Characterization and Terminal Velocities of Aluminium, Iron and Plastic Bottle Caps in a Water Environment. Recycling 2022, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Hamidian, A.H.; Tubić, A.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, J.K.; Wu, C.; Lam, P.K. Understanding plastic degradation and microplastic formation in the environment: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 274, 116554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Ocampo, I.Z.; Armstrong-Altrin, J.S. Abundance and composition of microplastics in Tampico beach sediments, Tamaulipas State, southern Gulf of Mexico. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 191, 114891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A.A.; Ampah, J.D.; Veza, I.; Atabani, A.E.; Hoang, A.T.; Nippae, A.; Powoe, M.T.; Afrane, S.; Yusuf, D.A.; Yahuza, I. Investigating the influence of plastic waste oils and acetone blends on diesel engine combustion, pollutants, morphological and size particles: Dehalogenation and catalytic pyrolysis of plastic waste. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 291, 117312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Ruz, V.; Gutow, L.; Thompson, R.C.; Thiel, M. Microplastics in the marine environment: A review of the methods used for identification and quantification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 3060–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koelmans, A.A.; Nor, N.H.M.; Hermsen, E.; Kooi, M.; Mintenig, S.M.; De France, J. Microplastics in freshwaters and drinking water: Critical review and assessment of data quality. Water Res. 2019, 155, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amelia, T.S.M.; Khalik, W.M.A.W.M.; Ong, M.C.; Shao, Y.T.; Pan, H.J.; Bhubalan, K. Marine microplastics as vectors of major ocean pollutants and its hazards to the marine ecosystem and humans. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2021, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, V.; Blázquez, G.; Calero, M.; Quesada, L.; Martín-Lara, M.A. The potential of microplastics as carriers of metals. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 255, 113363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retama, I.; Jonathan, M.; Shruti, V.; Velumani, S.; Sarkar, S.; Roy, P.D.; Rodríguez-Espinosa, P. Microplastics in tourist beaches of Huatulco Bay, Pacific coast of southern Mexico. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 113, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hantoro, I.; Löhr, A.J.; Van Belleghem, F.G.A.J.; Widianarko, B.; Ragas, A.M.J. Microplastics in coastal areas and seafood: Implications for food safety. Food Addit. Contam.—Part A Chem. Anal. Control. Expo. Risk Assess. 2019, 36, 674–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuerdo Mediante el Cual se Expide la Politica Nacional de Mares y Costas de Mexico. Available online: https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5545511&fecha=30/11/2018#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Álvarez-Lopeztello, J.; Robles, C.; del Castillo, R.F. Microplastic pollution in neotropical rainforest, savanna, pine plantations, and pasture soils in lowland areas of Oaxaca, Mexico: Preliminary results. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, L.J.; Ramírez-Romero, P.; Rodríguez-González, F.; Ramos-Sánchez, V.H.; Montes, R.A.M.; Rubio, H.R.-P.; Sujitha, S.; Jonathan, M. Seasonal evidences of microplastics in environmental matrices of a tourist dominated urban estuary in Gulf of Mexico, Mexico. Chemosphere 2021, 277, 130261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Altrin, J.S.; Ramos-Vázquez, M.A.; Madhavaraju, J.; Marca-Castillo, M.E.; Machain-Castillo, M.L.; Márquez-García, A.Z. Geochemistry of marine sediments adjacent to the Los Tuxtlas Volcanic Complex, Gulf of Mexico: Constraints on weathering and provenance. Appl. Geochem. 2022, 141, 105321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñon-Colin, T.d.J.; Rodriguez-Jimenez, R.; Pastrana-Corral, M.A.; Rogel-Hernandez, E.; Wakida, F.T. Microplastics on sandy beaches of the Baja California Peninsula, Mexico. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 131, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Álvarez, N.; Mendoza, L.M.R.; Macías-Zamora, J.V.; Oregel-Vázquez, L.; Alvarez-Aguilar, A.; Hernández-Guzmán, F.A.; Sánchez-Osorio, J.L.; Moore, C.J.; Silva-Jiménez, H.; Navarro-Olache, L.F. Microplastics: Sources and Distribution in Surface Waters and Sediments of Todos Santos Bay, Mexico. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703, 134838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peralta Pelaez, L.A.; Montes, C.P.; Castellanos, L.H.; Quero, O.D.J.H.; Hernández-Álvarez, C.; Estrella, I.A.M.; Rangel, B.S. Microplásticos en playas de la zona de influencia del Parque Nacional Sistema Arrecifal Veracruzano (PNSAV), México. Hidrobiológica 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, E. Demographic and urban impacts of tourism policies in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. E-Rev. Tour. Res. 2018, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Pelamatti, T.; Fonseca-Ponce, I.A.; Rios-Mendoza, L.M.; Stewart, J.D.; Marín-Enríquez, E.; Marmolejo-Rodriguez, A.J.; Hoyos-Padilla, E.M.; Galván-Magaña, F.; González-Armas, R. Seasonal variation in the abundance of marine plastic debris in Banderas Bay, Mexico. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 145, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medio Físico. Available online: https://www.puertovallarta.gob.mx/vistas/ciudad/medio-fisico.php#pagina_titulo (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Cruz-Romero, B.; Delgado-Quintana, J.A.; Téllez-López, J.; Carrillo González, F.M. Análisis socioeconómico de la cuenca del rio Cuale, Jalisco, México: Una contribución para la declaración del área natural protegida reserva de la biosfera el cuale. Rev. OIDLES 2013, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz Romero, B.; Gaspari, F.J.; Rodríguez Vagaría, A.M.; Carrillo González, F.M.; Téllez López, J. Análisis morfométrico de la cuenca hidrográfica del río Cuale, Jalisco, México. Investig. Y Cienc. De La Univ. Autónoma De Aguascalientes 2015, 23, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masura, J.; Baker, J.; Foster, G.; Arthur, C. Laboratory methods for the analysis of microplastics in the marine environment: Recommendations for quantifying synthetic particles in waters and sediments. NOAA Tech. Memo. NOS-ORR 2015, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, C.B.; Quinn, B. Microplastic Pollutants; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Torrez-Pérez, K.A.; Cervantes, O.; Reyes-Gomez, J. Quantification and Classification of Microplastics (Mps) in Urban, Suburban, Rural and Natural Beaches of Colima and Jalisco. México. Revista Costas 2020, 3, 207–230. [Google Scholar]

- Lozoya, J.P.; De Mello, F.T.; Carrizo, D.; Weinstein, F.; Olivera, Y.; Cedrés, F.; Pereira, M.; Fossati, M. Plastics and microplastics on recreational beaches in Punta del Este (Uruguay): Unseen critical residents? Environ. Pollut. 2016, 218, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, J.C.; da Costa, J.P.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. Methods for sampling and detection of microplastics in water and sediment: A critical review. TrAC—Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 110, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Book Microplastics in the Marine Environment: Sources, Fates, Impacts and Microbial Degradation, 3rd ed.; MDPI AG: Basel, Switzerland, 2008; pp. 154–196.

- Gondikas, A.; Mattsson, K.; Hassellöv, M. Methods for the detection and characterization of boat paint microplastics in the marine environment. Front. Environ. Chem. 2023, 4, 1090704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, S.; Moore, F.; Akhbarizadeh, R. Microplastic pollution in deposited urban dust, Tehran metropolis, Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 20360–20371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Tang, J.; Liu, R.; Wang, L. Toxicity in vitro reveals potential impacts of microplastics and nanoplastics on human health: A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 52, 3863–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanale, C.; Massarelli, C.; Savino, I.; Locaputo, V.; Uricchio, V.F. A Detailed Review Study on Potential Effects of Microplastics and Additives of Concern on Human Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osuna-Laveaga, D.R.; Ojeda-Castillo, V.; Flores-Payán, V.; Gutiérrez-Becerra, A.; Moreno-Medrano, E.D. Micro- and nanoplastics current status: Legislation, gaps, limitations and socio-economic prospects for future. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1241939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.-F.; Liu, G.-Z.; Zhu, Z.-L.; Wang, S.-C.; Zhao, F.-F. Interactions between microplastics and phthalate esters as affected by microplastics characteristics and solution chemistry. Chemosphere 2019, 214, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ran, W.; Teng, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Yin, X.; Cao, R.; Wang, Q. Microplastic pollution in sediments from the Bohai Sea and the Yellow Sea, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 640–641, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecen, V.; Seki, Y.; Sarikanat, M.; Tavman, I.H. FTIR and SEM analysis of polyester- and epoxy-based composites manufactured by VARTM process. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2008, 108, 2163–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B. The Infrared Spectra of Polymers II: Polyethylene. Spectroscopy 2021, 36, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorassini, A.; Adami, G.; Calvini, P.; Giacomello, A. ATR-FTIR characterization of old pressure sensitive adhesive tapes in historic papers. J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 21, 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B. The Infrared Spectra of Polymers III: Hydrocarbon Polymers. Spectroscopy 2021, 36, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strungaru, S.A.; Jijie, R.; Nicoara, M.; Plavan, G.; Faggio, C. Micro- (nano) plastics in freshwater ecosystems: Abundance, toxicological impact and quantification methodology. TrAC—Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 110, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Zeferino, J.C.; Ojeda-Benítez, S.; Cruz-Salas, A.A.; Martínez-Salvador, C.; Vázquez-Morillas, A. Microplastics in Mexican beaches. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Wontor, K.; Cizdziel, J.V.; Lu, H. Distribution and characteristics of microplastics in beach sand near the outlet of a major reservoir in north Mississippi, USA. Microplastics Nanoplastics 2022, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, C. The Quantification of Microplastics in Intertidal Sediments in the Bay of Fundy, Canada. Ph.D. Thesis, Royal Roads University, Victoria, BC, Canada, 2016; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Karthik, R.; Robin, R.; Purvaja, R.; Ganguly, D.; Anandavelu, I.; Raghuraman, R.; Hariharan, G.; Ramakrishna, A.; Ramesh, R. Microplastics along the beaches of southeast coast of India. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 1388–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, S.; Kerpen, J.; Prediger, J.; Barkmann, L.; Müller, L. Determination of the microplastics emission in the effluent of a municipal waste water treatment plant using Raman microspectroscopy. Water Res. X 2019, 2, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, A. Habitar las regiones urbanas turísticas. Seis formas de domesticar el espacio en la Región Puerto Vallarta—Bahía de Banderas en México. Ciudad. Y Entorno 2014, 9, 525–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Programa Playas Limpias, Agua y Ambiente Seguros (Proplayas). Available online: https://www.gob.mx/conagua/acciones-y-programas/programa-playas-limpias-agua-y-ambiente-seguros-proplayas#:~:text=Seguros%20(Proplayas).-,El%20Programa%20Playas%20Limpias%20tiene%20como%20objetivo%20proteger%20la%20salud,los%20sectores%20privado%2C%20social%20y (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Liu, M.; Lu, S.; Song, Y.; Lei, L.; Hu, J.; Lv, W.; Zhou, W.; Cao, C.; Shi, H.; Yang, X.; et al. Microplastic and mesoplastic pollution in farmland soils in suburbs of Shanghai, China. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 242, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, S.; Nakatani, J.; Saito, Y.; Fukushima, Y.; Yoshioka, T. Latest Trends and Challenges in Feedstock Recycling of Polyolefinic Plastics. J. Jpn. Pet. Inst. 2020, 63, 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Jimenez, M.A.; Rakotonirina, A.D.; Sainte-Rose, B.; Cox, D.J. On the Digital Twin of the Ocean Cleanup Systems—Part I: Calibration of the Drag Coefficients of a Netted Screen in OrcaFlex Using CFD and Full-Scale Experiments. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaremu, K.O.; Okoya, S.; Hughes, E.; Tijani, B.; Teidi, D.; Akpan, A.; Igwe, J.; Karera, S.; Oyinlola, M.; Akinlabi, E. Sustainable plastic waste management in a circular economy. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Location, Country | Number of Sample Sites | Abundant by Shape (1–5 mm) | Concentration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Puerto Vallarta Beach, Mexico | 48 | 41–24% fragments, 34–26% films, 30–24% foams, 18–1% pellets | 50–1230 particles/m2 20–49.2 particles/kg | Present study |

| Mexico, marine zone | 33 | 56% fragments, 15% foam, 11% fibers, 10% films, 8% pellets and others. | 31.7–545.8 particles/m2 | [48] |

| Baja California, Mexico | 71 | 91% fibers, 5% films, 3% pellets, 1% granules | 135 ± 92 particles/kg | [22] |

| Colima and Jalisco | 10 | 53% fragments, 40% fibers, 1% films, 6% granules. | 2553.4 ± 1895.8 particles/kg | [32] |

| Tamaulipas State, southern Gulf of Mexico | 20 | 100% fibers | 13,392 particles/kg | [10] |

| Estuary in Gulf of Mexico | 71% fibers, 29% fragments | 121 ± 115 particles/kg | [20] | |

| Oaxaca, Mexico | 11 | Fibers and fragments | 1530 and 1490 particles/kg | [19] |

| Todos Santos Bay, Mexico | 11 | 19–70% fragments, 18–28% fibers | 85–2494 particles/m2 | [23] |

| Banderas Bay, Mexico | 57 | 41% films, 40% fragments, 11% line, 8% fibers | 69 particles/m2 | [26] |

| Huatulco Bay, Mexico | 35 | Fibers | 200–6900 particles/kg | [16] |

| Veracruz Reef System, Mexico | 92.35% fragments, 4.12% fibers, 1.76% pellets, 1.76% films | 4.5 particles/m2 | [24] | |

| Mississippi, USA | 15 | 61% fibers, 25% fragments, 8% beads, 6% films. | 590 ± 360 particles/kg | [49] |

| Canada | 15 | 89% fibers, 8% fragments, 2% pellets | 268 particles/kg | [50] |

| India | 25 | 47–50% fragments, 24–27% fibers, 10–19% foams | 48.9 to 4747.6 mg/m2 | [51] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mejía-Estrella, I.A.; Peña-Montes, C.; Peralta-Peláez, L.A.; Del Real Olvera, J.; Sulbarán-Rangel, B. Microplastics in Sandy Beaches of Puerto Vallarta in the Pacific Coast of Mexico. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115259

Mejía-Estrella IA, Peña-Montes C, Peralta-Peláez LA, Del Real Olvera J, Sulbarán-Rangel B. Microplastics in Sandy Beaches of Puerto Vallarta in the Pacific Coast of Mexico. Sustainability. 2023; 15(21):15259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115259

Chicago/Turabian StyleMejía-Estrella, Ixchel Alejandra, Carolina Peña-Montes, Luis Alberto Peralta-Peláez, Jorge Del Real Olvera, and Belkis Sulbarán-Rangel. 2023. "Microplastics in Sandy Beaches of Puerto Vallarta in the Pacific Coast of Mexico" Sustainability 15, no. 21: 15259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115259

APA StyleMejía-Estrella, I. A., Peña-Montes, C., Peralta-Peláez, L. A., Del Real Olvera, J., & Sulbarán-Rangel, B. (2023). Microplastics in Sandy Beaches of Puerto Vallarta in the Pacific Coast of Mexico. Sustainability, 15(21), 15259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115259