Local Public Administration in the Process of Implementing Sustainable Development Goals

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Local Governments and the Sustainable Development Goals

2. Materials and Methods

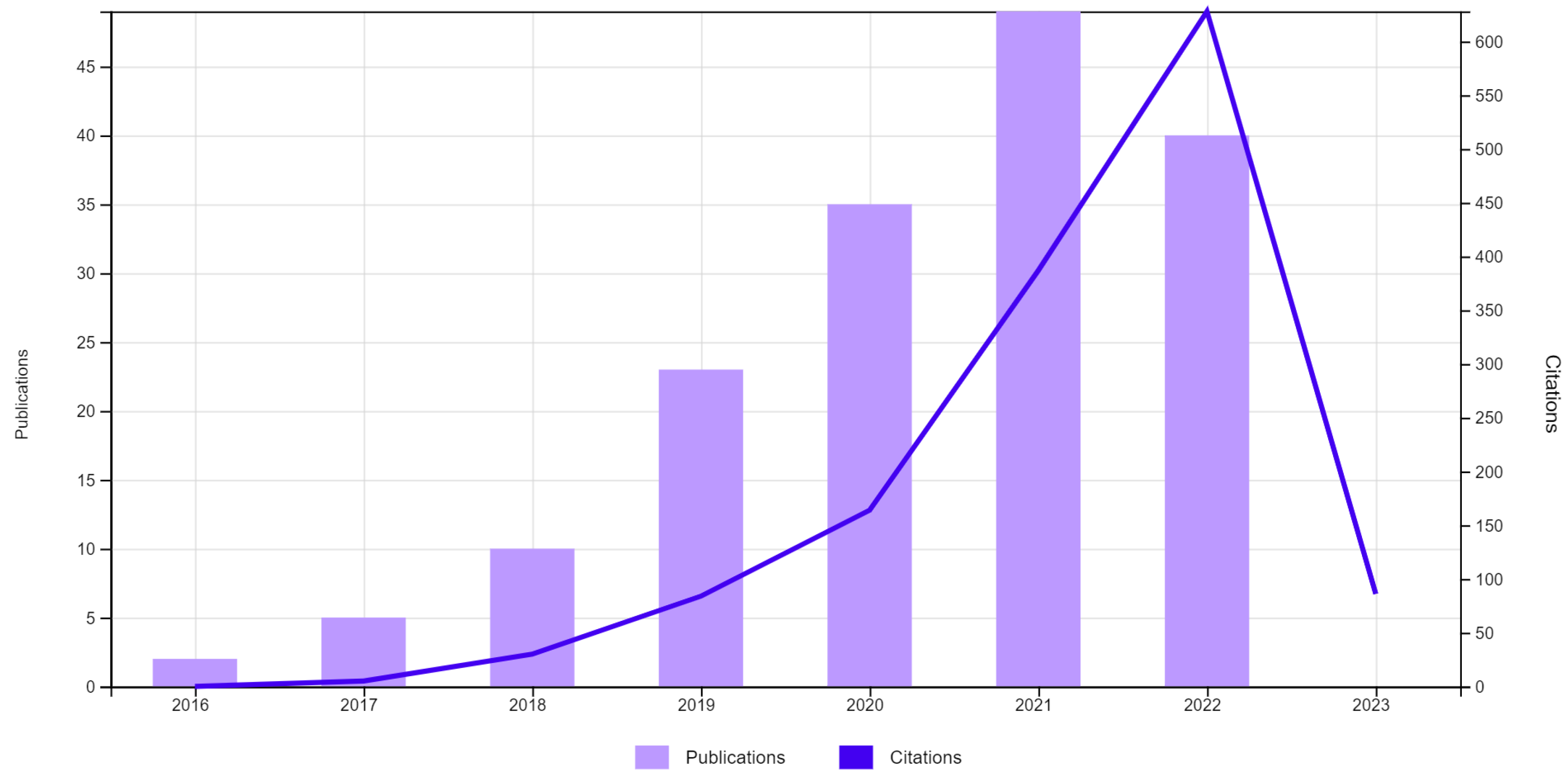

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. SDG Categories and Their Implications for LPAs

3.1.1. SDGs with Social Goals

3.1.2. SDGs with Economic Goals

3.1.3. SDGs with Environmental Goals

3.1.4. SDG 17 Effective Partnerships

3.2. Co-Word and Graphical Analyses

3.2.1. Network Analysis

3.2.2. Density Analysis

3.2.3. Cluster Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Government Area

4.2. Development Area

4.3. Environmental Area

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Opportunities

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UN | United Nations |

| SD | Sustainable development |

| SDG | Sustainable development goal |

| MDG | Millennium development goal |

| LPA | Local public administration |

| WoS | Web of science |

| TCA | Thematic content analysis |

References

- Plum, A.; Kaljee, L. Achieving Sustainable, Community-Based Health in Detroit Through Adaptation of the UNSDGs. Ann. Glob. Health 2016, 82, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, C.; Zulu, L.C. From the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Africa in the post-2015 development Agenda. A geographical perspective. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2017, 36, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.K.; Mishra, I. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 and environmental sustainability: Race against time. Environ. Sustain. 2019, 2, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, I.; Domingues, A.R.; Caeiro, S.; Painho, M.; Antunes, P.; Santos, R.; Videira, N.; Walker, R.M.; Huisingh, D.; Ramos, T.B. Sustainability policies and practices in public sector organisations: The case of the Portuguese Central Public Administration. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M.H.M.; Troshani, I.; Davidson, R. Public sector adoption of social media. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2015, 55, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmotaleb, M.; Saha, S.K. Corporate Social Responsibility, Public Service Motivation and Organizational Citizenship Behavior in the Public Sector. Int. J. Public Adm. 2019, 42, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Stankevičiūtė, Ž.; Robina-Ramirez, R.; Díaz-Caro, C. Responsible job design based on the internal social responsibility of local governments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, S.D.S.; Borini, F.M.; Avrichir, I. Environmental upgrading and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunati, S.; Martiniello, L.; Morea, D. The strategic role of the corporate social responsibility and circular economy in the cosmetic industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Lamata, M.; Latorre-Martínez, M.P. The Circular Economy and Sustainability: A Systematic Literature Review. Manag. Lett. Cuad. Gest. 2022, 22, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayu Purnamawati, I.G.; Yuniarta, G.A.; Jie, F. Strengthening the role of corporate social responsibility in the dimensions of sustainable village economic development. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galan-Ladero, M.M.; Sánchez-Hernández, M.I. Corporate donation behavior during the covid-19 pandemic. A case-study approach in the multinational inditex. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuedi, H.; Sanagustín-Fons, V.; Galiano Coronil, A.; Moseñe-Fierro, J.A. Analysis of tourism sustainability synthetic indicators. A case study of Aragon. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbett, J.; Mellouli, S. Winning the SDG battle in cities: How an integrated information ecosystem can contribute to the achievement of the 2030 sustainable development goals. Inf. Syst. J. 2017, 27, 427–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grueso-Gala, M.; Zornoza, C.C. A bibliometric analysis of the literature on non-financial information reporting: Review of the research and network visualization. Manag. Lett. Cuad. Gest. 2022, 22, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, K.; Schaltegger, S.; Crutzen, N. Integrating corporate sustainability assessment, management accounting, control, and reporting. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz-Quiles, F.J.; Navarro-Galera, A.; Ortiz-Rodríguez, D. La transparencia sobre sostenibilidad en gobiernos regionales: El caso de España. Convergencia 2017, 24, 113–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L.C.; Vázquez, D.G.; Gil, M.T.N. Local Municipalities’ Involvement in Promoting Entrepreneurship; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevado Gil, M.T.; Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Carvalho, L. Entrepreneurship in a local government: An empirical study of information in the websites of antalejo region municipalities. Innovar 2019, 29, 97–112. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wataya, E.; Shaw, R. Measuring the value and the role of soft assets in smart city development. Cities 2019, 94, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozos-Blanco, M.Á.; Pozo-Menéndez, E.; Arce-Ruiz, R.; Baucells-Aletà, N. The way to sustainable mobility. A comparative analysis of sustainable mobility plans in Spain. Transp. Policy 2018, 72, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Xia, M.; Zhang, Q.; Elahi, E.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H. The impact of public appeals on the performance of environmental governance in China: A perspective of provincial panel data. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilsky, E.; Moreno, A.C.; Fernández Tortosa, A. Local Governments and SDG Localisation: Reshaping Multilevel Governance from the Bottom up. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 2021, 22, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Valbuena, N.A.; Valenzuela-Fernández, L.; Merigó, J.M. Thirty-five years of strategic management research. A country analysis using bibliometric techniques for the 1987–2021 period. Cuad. Gest. 2022, 22, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I.; Čater, T. Bibliometric Methods in Management and Organization. Organ. Res. Methods 2015, 18, 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Gustafsson, A. Investigating the emerging COVID-19 research trends in the field of business and management: A bibliometric analysis approach. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 118, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazandarani, M.R.; Royo-Vela, M. Firms’ internationalization through clusters: A keywords bibliometric analysis of 152 top publications in the period 2009–2018. Manag. Lett. Cuad. Gest. 2022, 22, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annesi, N.; Battaglia, M.; Gragnani, P.; Iraldo, F. Integrating the 2030 Agenda at the municipal level: Multilevel pressures and institutional shift. Land Use Policy 2021, 105, 105424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, E.; Vijge, M.J. From Millennium to Sustainable Development Goals: Evolving discourses and their reflection in policy coherence for development. Earth Syst. Gov. 2021, 7, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, G.; Szopik-Depczyńska, K.; Dembińska, I.; Ioppolo, G. Smart and sustainable logistics of Port cities: A framework for comprehending enabling factors, domains and goals. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 69, 102801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moggi, S.; Bonomi, S.; Ricciardi, F. Against food waste: CSR for the social and environmental impact through a network-based organizational model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Xue, X.; Tian, H.; Michael, A.U. How will China realize SDG 14 by 2030?—A case study of an institutional approach to achieve proper control of coastal water pollution. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 230, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.; Possingham, H.; Rhodes, J.R.; Mumby, P. Food, money and lobsters: Valuing ecosystem services to align environmental management with Sustainable Development Goals. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 29, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Kumar, A.; Pramanik, M.; Negi, M.S. Land Evaluation and Sustainable Development of Ecotourism in the Garhwal Himalayan Region Using Geospatial Technology and Analytical Hierarchy Process; Springer: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 24, pp. 2225–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgewater, P.; Régnier, M.; García, R.C. Implementing SDG 15: Can large-scale public programs help deliver biodiversity conservation, restoration and management, while assisting human development? Nat. Resour. Forum 2015, 39, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 17 September 2023).

- Castillo-Villar, R.G. Identifying determinants of CSR implementation on SDG 17 partnerships for the goals. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1847989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F. The Contribution of Local Agents and Citizens to Sustainable Development: The Portuguese Experience. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiu, V.; Blečić, I.; Meloni, I. Making sustainability development goals (SDGs) operational at suburban level: Potentials and limitations of neighbourhood sustainability assessment tools. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 96, 106845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baena, J.; García-Serrano, J.d.D.; Toro-Peña, O.; Vela-Jiménez, R. The Influence of the Organizational Culture of Andalusian Local Governments on the Localization of Sustainable Development Goals. Land 2022, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakely, P. Partnership: A strategic paradigm for the production & management of affordable housing & sustainable urban development. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2020, 12, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.E.; Battaglia, M.; Calabrese, M.; Simone, C. Fostering sustainable cities through resilience thinking: The role of nature-based solutions (NBSS): Lessons learned from two Italian case studies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, S.K.; Das, P.; Maity, B.; Rudra, S.; Pramanik, M.; Pradhan, B.; Sahana, M. Understanding future urban growth, urban resilience and sustainable development of small cities using prediction-adaptation-resilience (PAR) approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, G.; Chauhan, S.S.; Varma, R. Challenges of localizing sustainable development goals in small cities: Research to action. IATSS Res. 2021, 45, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zotova, O.; Pineo, H.; Siri, J.; Liang, L.; Luo, X.; Kwan, M.P.; Ji, J.; Jiang, X.; et al. Healthy cities initiative in China: Progress, challenges, and the way forward. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2022, 27, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, T.; Huang, M. China’s River Chief Policy and the Sustainable Development Goals: Prefecture-Level Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, C.; Graziano, P.; Lazzarini, M.; Piras, S.; Spaghi, S. Sustainable Community Movement Organisations and household food waste: The missing link in urban food policies? Cities 2022, 122, 103473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, H.; Fagerholm, A.S.; Carlsson, P.; Skoglund, W.; van den Brink, P.; Danielski, I.; Brink, K.; Mirata, M.; Englund, O. Towards a Resilient and Resource-Efficient Local Food System Based on Industrial Symbiosis in Härnösand: A Swedish Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerland, R.; Nilsen, H.R.; Andersen, B. Biosphere-based sustainability in local governments: Sustainable development goal interactions and indicators for policymaking. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, H.; Okitasari, M.; Morita, K.; Katramiz, T.; Shimizu, H.; Kawakubo, S.; Kataoka, Y. SDGs mainstreaming at the local level: Case studies from Japan. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1539–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunović, I.; Müller, C.; Deimel, K. Building a Culture of Entrepreneurial Initiative in Rural Regions Based on Sustainable Development Goals: A Case Study of University of Applied Sciences–Municipality Innovation Partnership. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, I.; Chapman, T.; Dudfield, O. Configuring relationships between state and non-state actors: A new conceptual approach for sport and development. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2020, 12, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Swapan, M.S.H.; Khan, S. Sustainable mobility through safer roads: Translating road safety strategy into local context in western australia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maconachie, R.; Conteh, F. Artisanal mining policy reforms, informality and challenges to the Sustainable Development Goals in Sierra Leone. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 116, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annan-Aggrey, E.; Arku, G.; Atuoye, K.; Kyeremeh, E. Mobilizing ‘communities of practice’ for local development and accleration of the Sustainable Development Goals. Local Econ. 2022, 37, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, A.M.; Guillamón, M.D.; Cifuentes-Faura, J.; Benito, B. Efficiency and sustainability in municipal social policies. Soc. Policy Adm. 2022, 56, 1103–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meschede, C. Information dissemination related to the Sustainable Development Goals on German local governmental websites. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 71, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarska-Olejniczak, D.; Olejniczak, J.; Svobodová, L. How a participatory budget can support sustainable rural development-lessons from Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, G.; Bromaghim, E.; Kim, A.; Diamond, C.; Maggini, A.; Everhart, A.; Gruskin, S.; Chase, A.T. Classroom walls and city hall: Mobilizing local partnerships to advance the sustainable development agenda. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, J.L.; Niaounakis, T.K. Economies of scale and sustainability in local government: A complex issue. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurui, L.; Xuanchang, Z.; Zhi, C.; Zhengjia, L.; Zhi, L.; Yansui, L. Towards the progress of ecological restoration and economic development in China’s Loess Plateau and strategy for more sustainable development. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 143676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Q.; Musango, J.K. A Conceptual Approach to the Stakeholder Mapping of Energy Lab in Poor Urban Settings. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.S.K.; Okitasari, M.; Ahsan, M.R.; Al-Amin, A.Q. Localisation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Bangladesh: An Inclusive Framework under Local Governments. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hone, T.; Rasella, D.; Barreto, M.L.; Majeed, A.; Millett, C. Association between expansion of primary healthcare and racial inequalities in mortality amenable to primary care in Brazil: A national longitudinal analysis. PLoS Med. 2017, 14, e1002306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masefield, S.C.; Msosa, A.; Grugel, J. Challenges to effective governance in a low income healthcare system: A qualitative study of stakeholder perceptions in Malawi. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yang, B.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, R.; Tang, S.; Story, M. Improving maternal and child nutrition in China: An analysis of nutrition policies and programs initiated during the 2000–2015 Millennium Development Goals era and implications for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2020, 39, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oladosun, M.; Azuh, D.; Chinedu, S.N.; Azuh, A.E.; Ayodele, E.; Nwogu, F. Determinants of perceived quality of health care among pregnant women in Ifo, Ogun State, Nigeria. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2021, 25, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kanyagui, M.K.; Viswanathan, P.K. Water and sanitation services in India and Ghana: An assessment of implications for rural health and related SDGs. Water Policy 2022, 24, 1073–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namin, S.; Ko, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Beyer, K. Discourse analysis of the perceptions of environmental justice and respiratory health disparities in Dallas, TX. Local Environ. 2022, 27, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, Y. Taking a future generation’s perspective as a facilitator of insight problem-solving: Sustainable water supply management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrard, N.; Neumeyer, H.; Pati, B.K.; Siddique, S.; Choden, T.; Abraham, T.; Gosling, L.; Roaf, V.; Torreano, J.A.S.; Bruhn, S. Designing human rights for duty bearers: Making the human rights to water and sanitation part of everyday practice at the local government level. Water 2020, 12, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhonju, H.K.; Uprety, B.; Xiao, W. Geo-Enabled Sustainable Municipal Energy Planning for Comprehensive Accessibility: A Case in the New Federal Context of Nepal. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iduseri, E.O.; Izunobi, J.U.; Oyelami, O.A. Sustainable Development Goal 2 (SDG-2) and the Challenges of Transporting Agricultural Produce: A Case Study of Esan-West Local Government Area of Edo State, Nigeria. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almadrones-Reyes, K.J.; Dagamac, N.H.A. Land-use/land cover change and land surface temperature in Metropolitan Manila, Philippines using landsat imagery. GeoJournal 2023, 88, 1415–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Sun, Z.; Lu, L.; Xiong, Z.; Cui, L.; Mao, Z. Rapid expansion of coastal aquaculture ponds in Southeast Asia: Patterns, drivers and impacts. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 315, 115100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudau, N.; Mhangara, P. Towards understanding informal settlement growth patterns: Contribution to SDG reporting and spatial planning. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2022, 27, 100801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienow, A.; Kantakumar, L.N.; Ghazaryan, G.; Dröge-Rothaar, A.; Sticksel, S.; Trampnau, B.; Thonfeld, F. Modelling the spatial impact of regional planning and climate change prevention strategies on land consumption in the Rhine-Ruhr Metropolitan Area 2017–2030. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 217, 104284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.; Maher, J.; Swapan, M.S.H.; Zaman, A. Street Verge in Transition: A Study of Community Drivers and Local Policy Setting for Urban Greening in Perth, Western Australia. Urban Sci. 2022, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligorio, L.; Venturelli, A.; Caputo, F. Tracing the boundaries between sustainable cities and cities for sustainable development. An LDA analysis of management studies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 176, 121447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, T.B.; Battistelle, R.A.; Teixeira, A.A.; Mariano, E.B.; Moraes, T.E. The Sustainable Development Goals Implementation: Case Study in a Pioneer Brazilian Municipality. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Jahan, C.S.; Rahaman, M.F.; Mazumder, Q.H. Governance status in water management institutions in Barind Tract, Northwest Bangladesh: An assessment based on stakeholder’s perception. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2020, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambo, C.; Senzanje, A.; Mutanga, O. Assessing inequalities in sustainable access to improved water services using service level indicators in a rural municipality of South Africa. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2021, 11, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhajed-Picha, P.; Narayanan, N.C. Refining the shit flow diagram using the capacity-building approach—Method and demonstration in a south Indian town. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 294, 112971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronk, R.; Guo, A.; Fleming, L.; Bartram, J. Factors associated with water quality, sanitation, and hygiene in rural schools in 14 low- and middle-income countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 761, 144226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.J.; Broadhurst, J.L. Sustainable Development in Mining Communities: The Case of South Africa’s West Wits Goldfield. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 895760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondhalekar, D.; Erlbeck, R. Application of the Nexus Approach as an Integrated Urban Planning Framework: From Theory to Practice and Back Again. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 751682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, S.; Clarke, A.; Tozer, L. Strategies and governance for implementing deep decarbonization plans at the local level. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Watson, A.E.; Zhao, X. Improving herders’ income through alpine grassland husbandry on Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Land Use Policy 2022, 113, 105896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, M.R.; Daguio, K.G.L.; Gamboa, M.A.M. City Profile: Batangas City, Philippines. Environ. Urban. ASIA 2019, 10, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, F.C.R.; Gasperin, D. Sustainable City Development: A Brazilian Goal Plan in Practice. J. Innov. Sustain. RISUS 2021, 12, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Córdoba, P.J.; Amor-Esteban, V.; Benito, B.; García-Sánchez, I.M. The commitment of spanish local governments to sustainable development goal 11 from a multivariate perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, B.; Diprose, K.; Taylor Buck, N.; Simon, D. Localizing the SDGs in England: Challenges and Value Propositions for Local Government. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 746337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yomthong, K.; Wattanasiriwech, S.; Wattanasiriwech, D. Paving block mortars made with mixed waste glass from municipality. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Waste Resour. Manag. 2022, 176, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, I.; Ali, A.; Bayyati, A. The station location and sustainability of high-speed railway systems. Infrastruct. Asset Manag. 2021, 9, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Aguilar-Yuste, M.; Maldonado-Briegas, J.J.; Seco-González, J.; Barriuso-Iglesias, C.; Galán-Ladero, M.M. Modelling municipal Social Responsibility: A pilot study in the Region of Extremadura (Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 6887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quitzau, M.B.; Gustafsson, S.; Hoffmann, B.; Krantz, V. Sustainability coordination within forerunning Nordic municipalities—Exploring structural challenges across departmental silos and hierarchies. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 335, 130330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SDGs Categories | Total Frequency | Percentage (%) | Disclosure Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social | 63 | 38.4% | 1st Place |

| Economic | 26 | 15.9% | 4th Place |

| Environmental | 41 | 25% | 2nd Place |

| SDG 17 | 34 | 20.7% | 3rd Place |

| 164 | 100% |

| Areas | Clusters |

|---|---|

| Government Area | Cluster 1—2030 Agenda Implementation |

| Cluster 8—Local Government Initiatives | |

| Development Area | Cluster 2—Stakeholder Engagement |

| Cluster 3—Health | |

| Cluster 4—Impactful Solutions | |

| Cluster 5—Urban Dynamics | |

| Environment Area | Cluster 6—Water |

| Cluster 7—Urban Sustainability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, A.F.; Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Carvalho, L.C. Local Public Administration in the Process of Implementing Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15263. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115263

Silva AF, Sánchez-Hernández MI, Carvalho LC. Local Public Administration in the Process of Implementing Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability. 2023; 15(21):15263. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115263

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Ana Filipa, M. Isabel Sánchez-Hernández, and Luísa Cagica Carvalho. 2023. "Local Public Administration in the Process of Implementing Sustainable Development Goals" Sustainability 15, no. 21: 15263. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115263

APA StyleSilva, A. F., Sánchez-Hernández, M. I., & Carvalho, L. C. (2023). Local Public Administration in the Process of Implementing Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability, 15(21), 15263. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115263