The Impact of Regional Socio-Economic Development on Spatial and Temporal Differences in the Distribution Pattern of Top-Tier Education in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Literature Review

2.1. Studies on the Higher Education System in China and the Connotation of “Double First-Class”

2.2. Studies on the Impact of Regional Socio-Economic Development on Higher Education

2.3. The Socio-Economic Impact of Higher Education

2.4. Studies on the Distribution Pattern of Higher Education Disciplines

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Sources

3.3. Indicator Selection

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

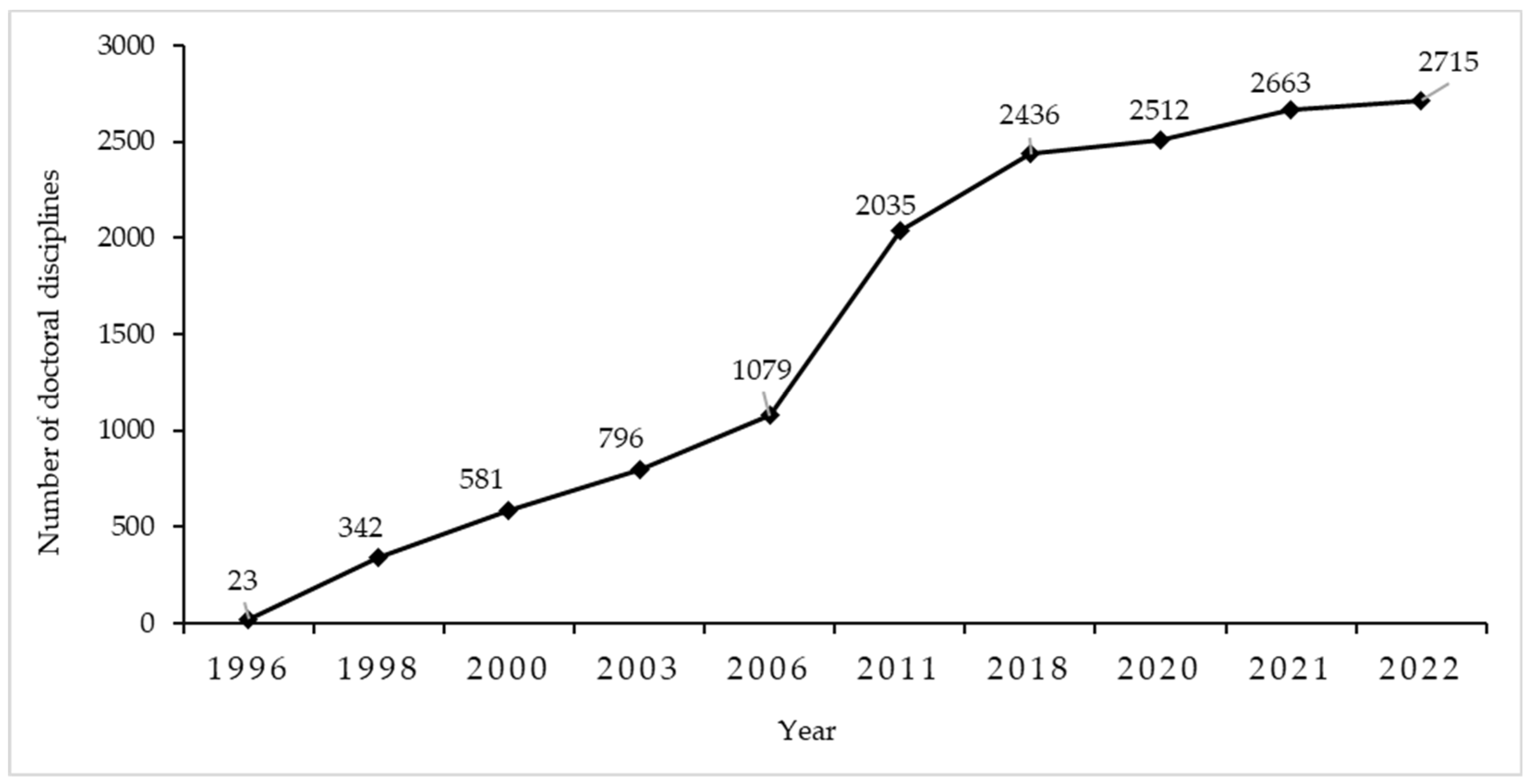

4.1. Dynamic Changes in the Number of Doctoral Disciplines in “Double First-Class” Universities

4.1.1. Temporal Changes in the Number of Doctoral Disciplines in China

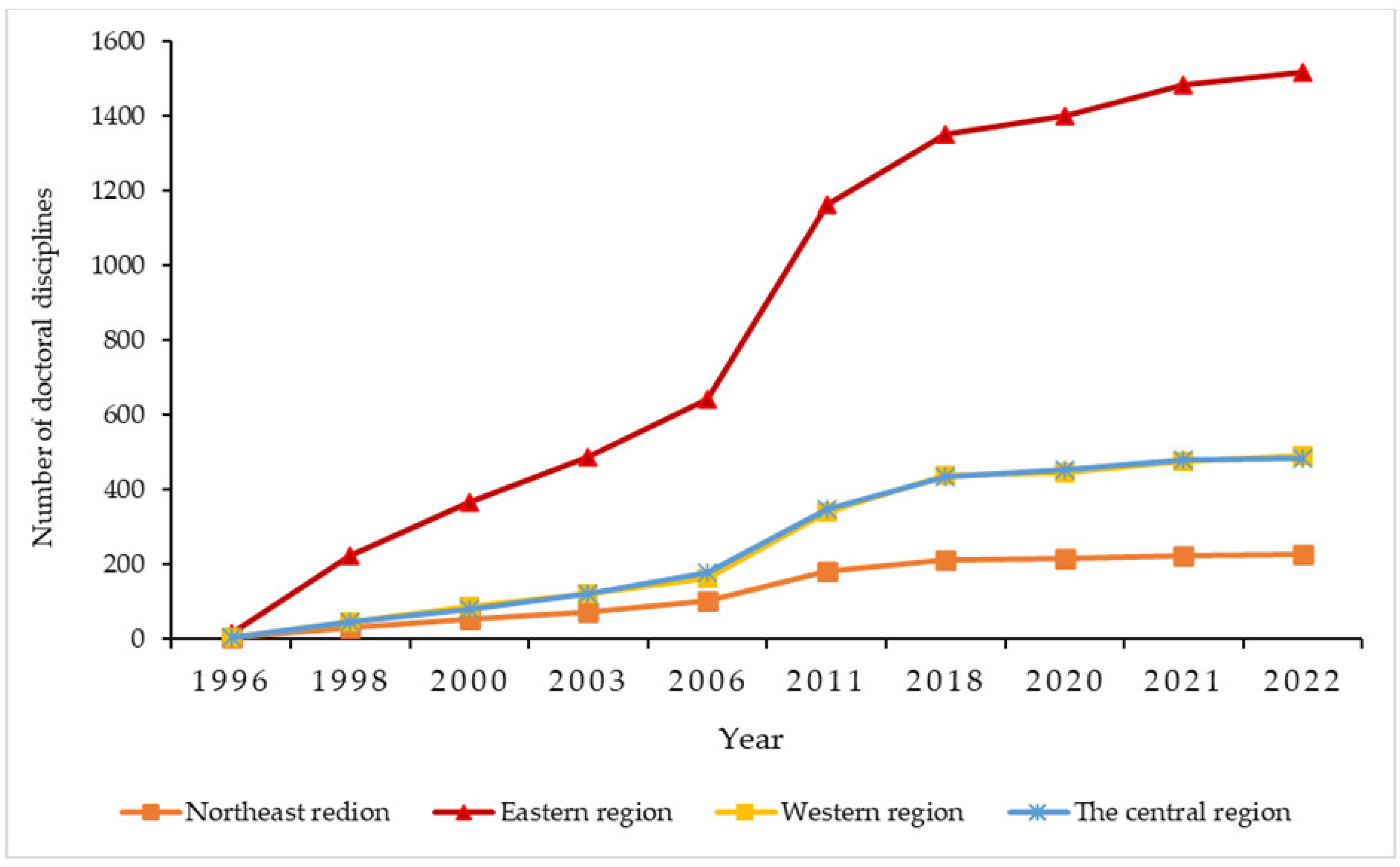

4.1.2. Temporal Changes in the Number of Doctoral Disciplines in Different Economic Divisions

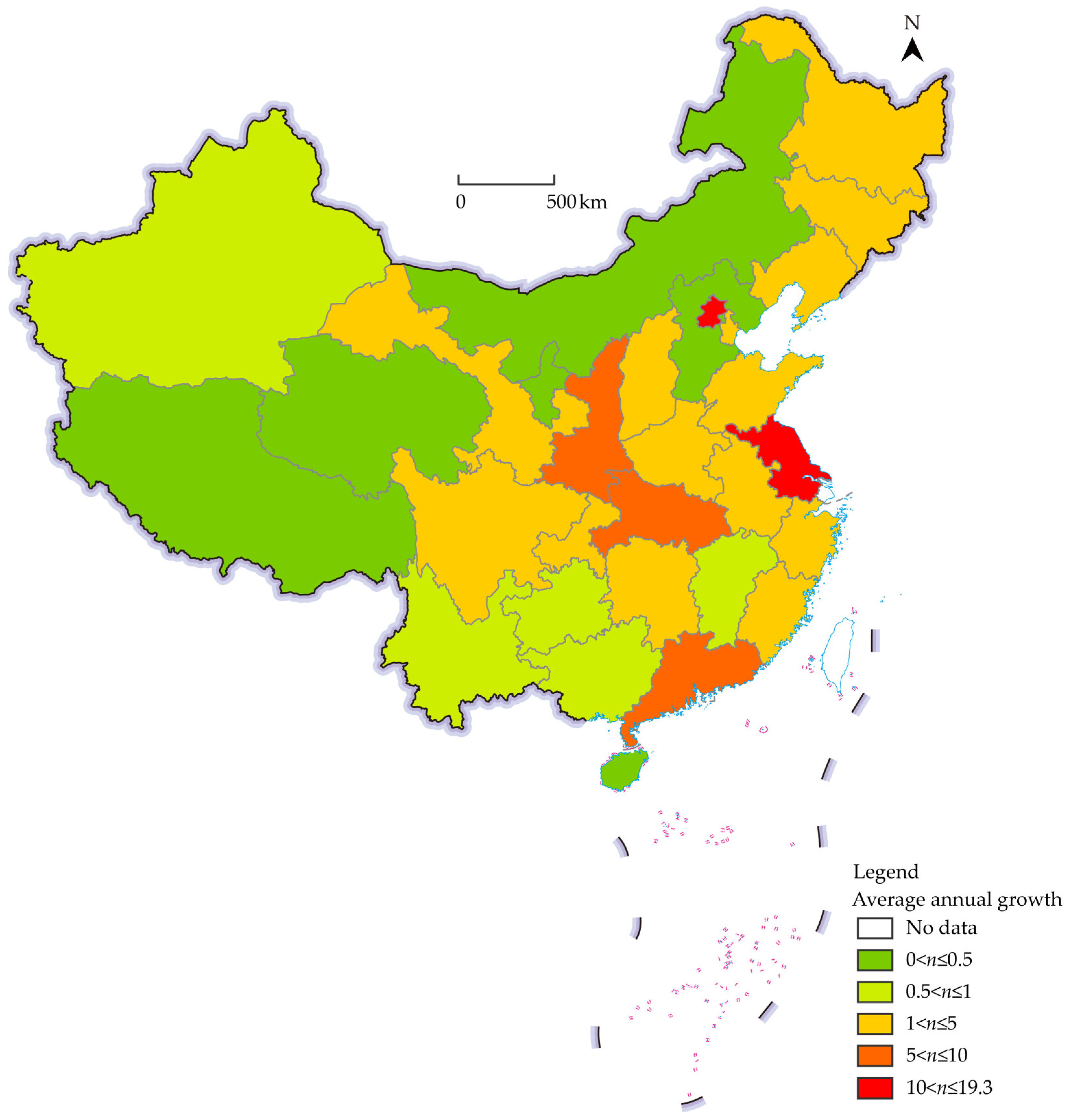

4.1.3. Temporal Changes in the Number of Doctoral Disciplines in Different Provinces

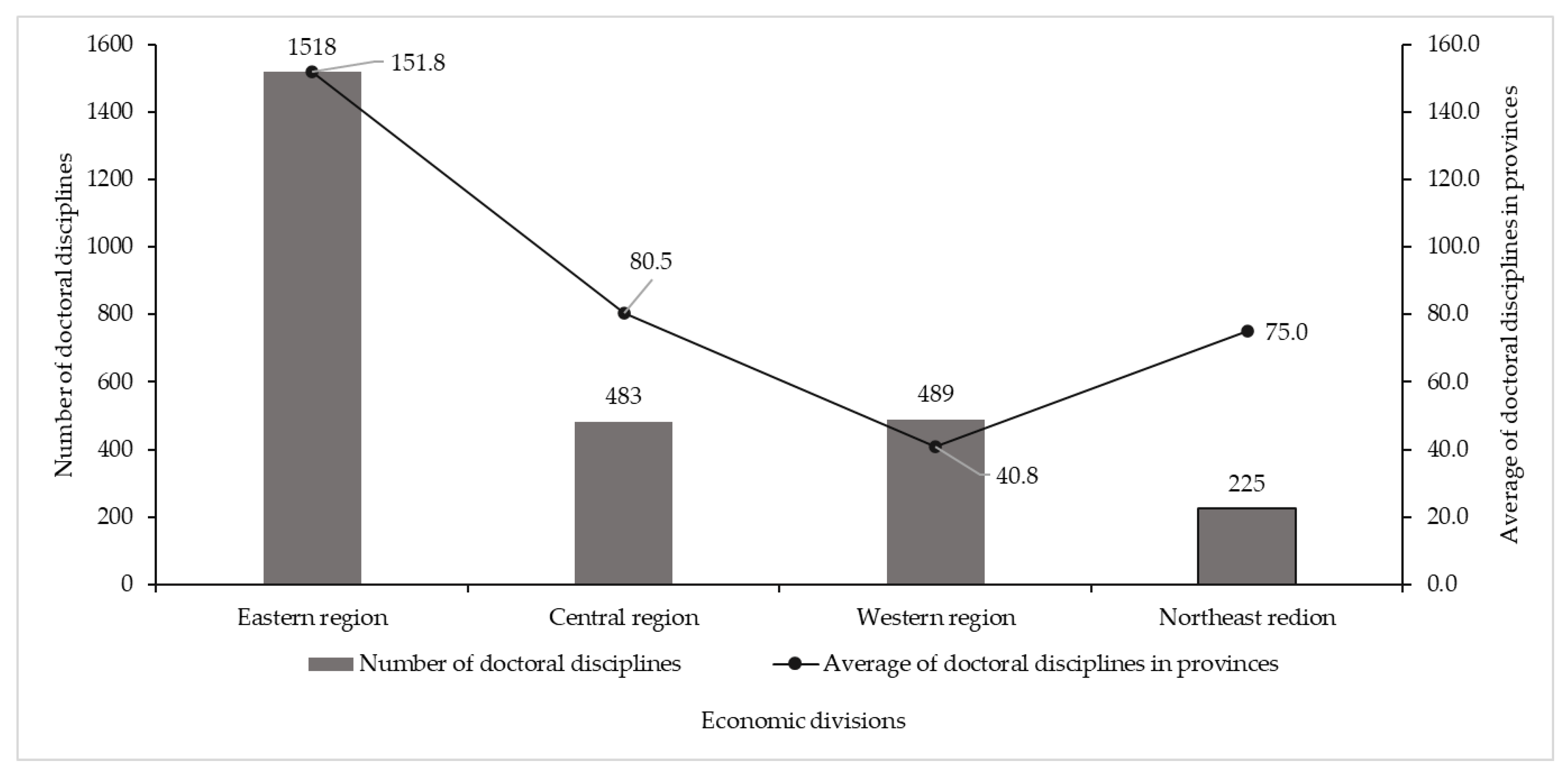

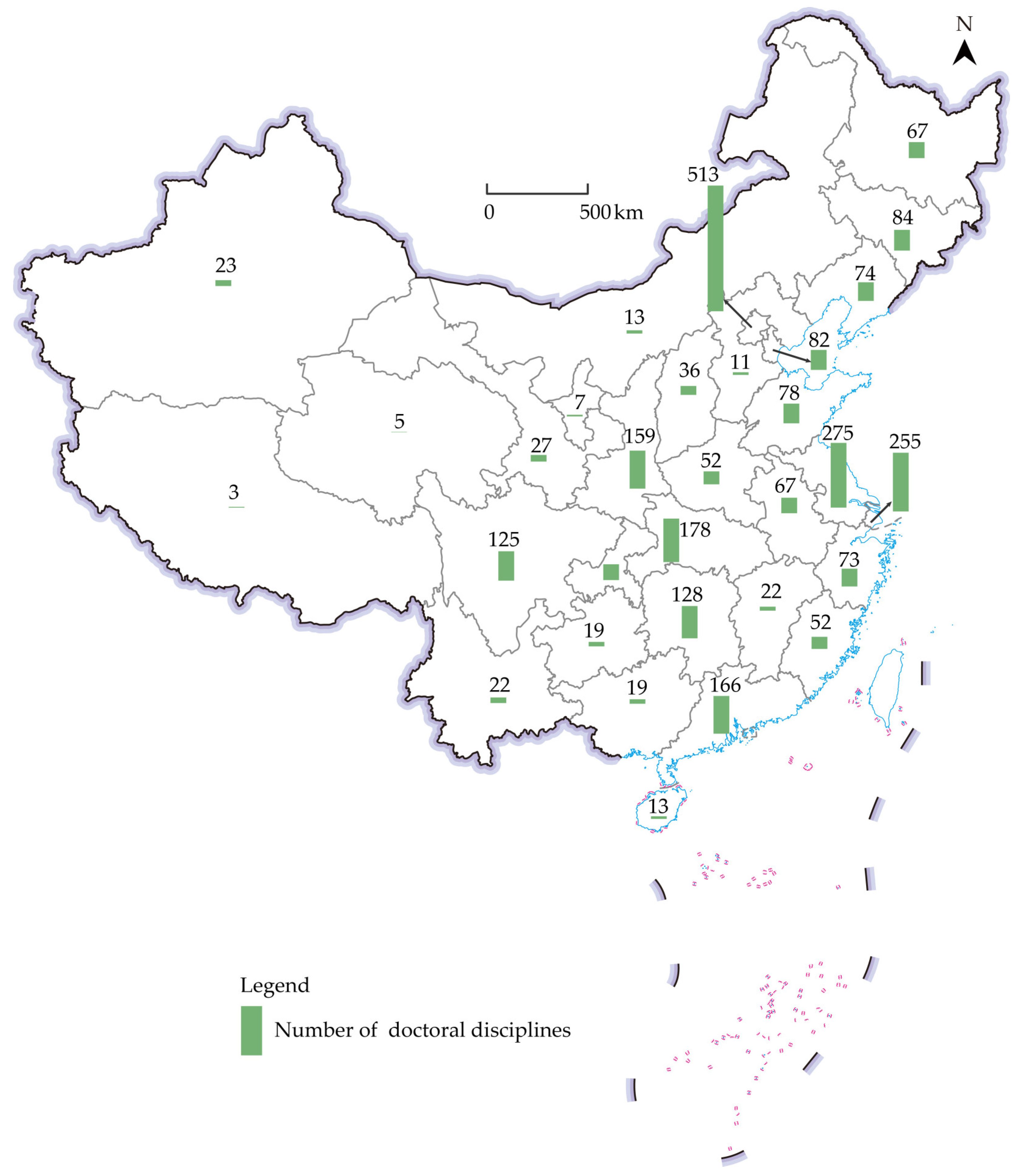

4.2. Spatial Distribution Pattern of the Number of Doctoral Disciplines in “Double First-Class” Universities

4.2.1. Spatial Changes in the Number of Doctoral Disciplines in Different Economic Divisions

4.2.2. Spatial Changes in the Number of Doctoral Disciplines in Different Provinces

4.3. Spatial Distribution Differences in the Quality of Doctoral Disciplines in “Double First-Class” Universities

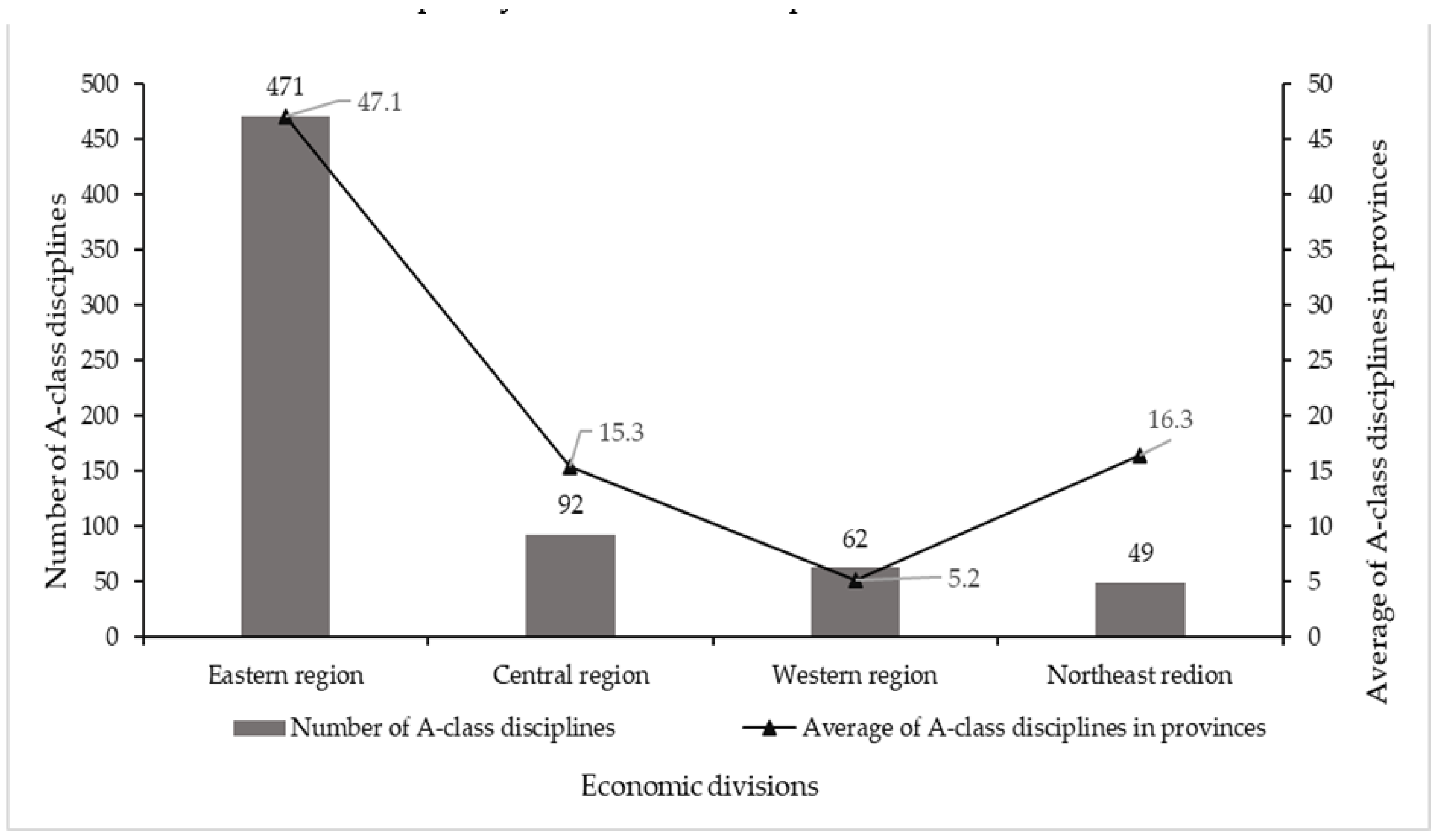

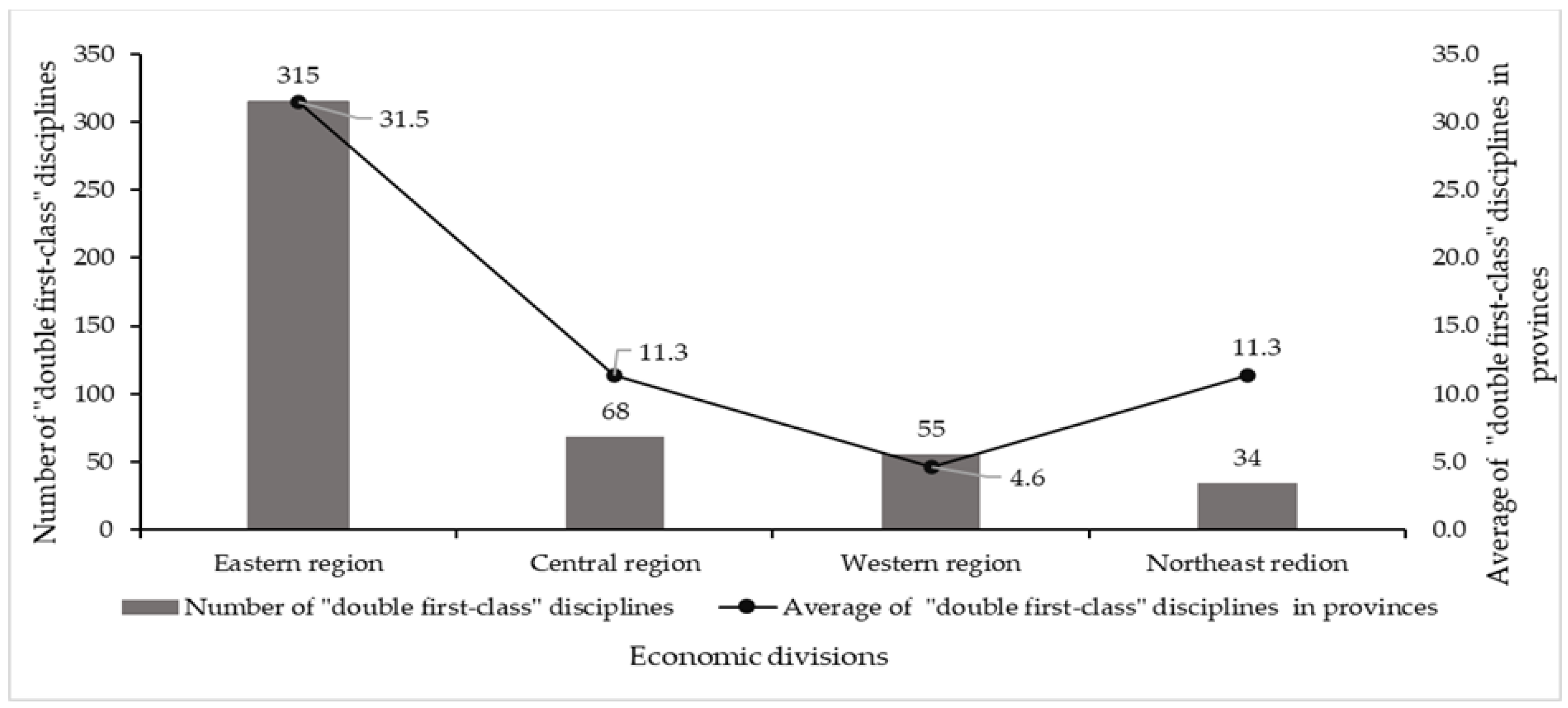

4.3.1. Distribution of the Quality of Doctoral Disciplines in Different Economic Divisions

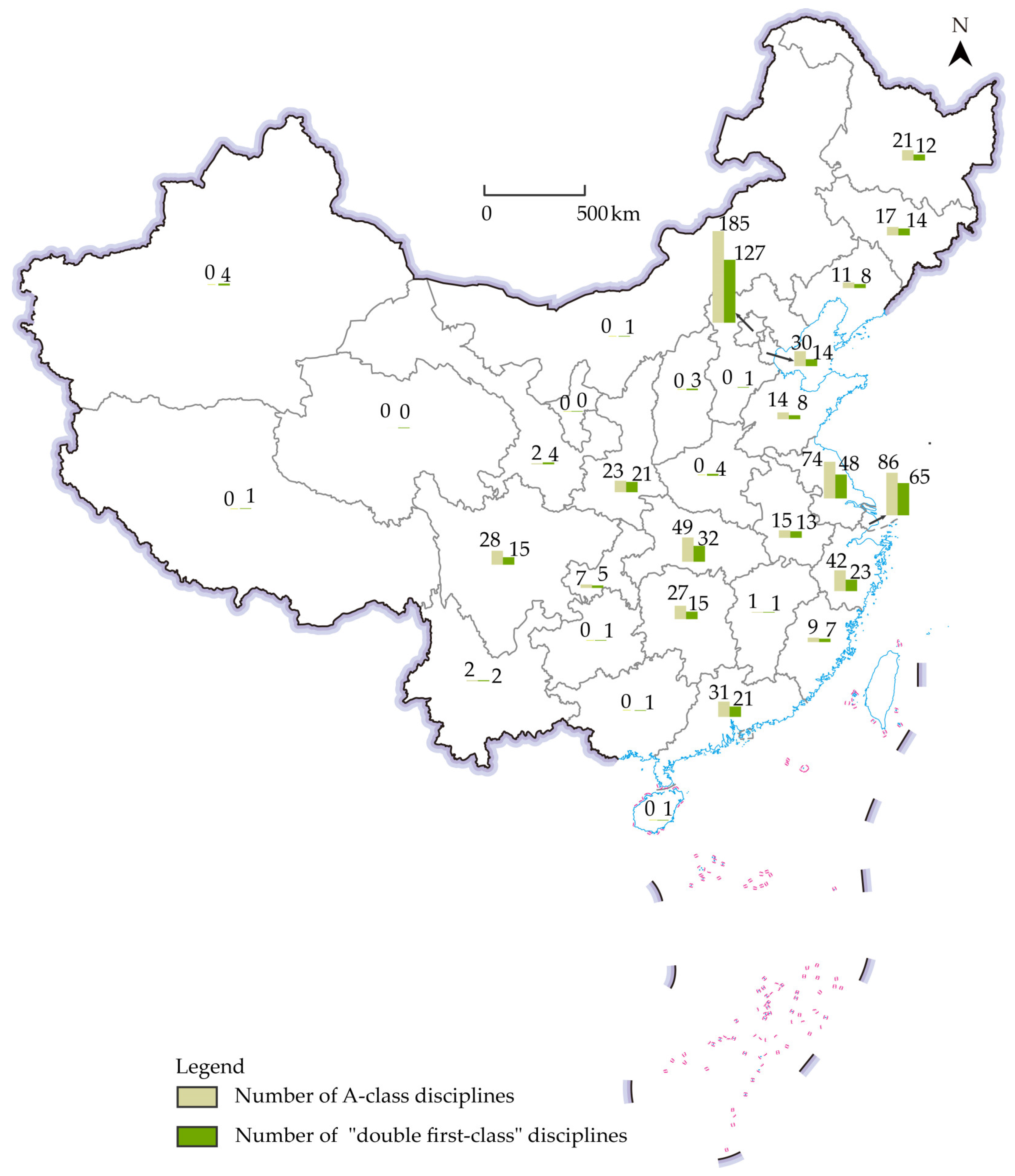

4.3.2. Distribution of the Quality of Doctoral Disciplines in Different Provinces

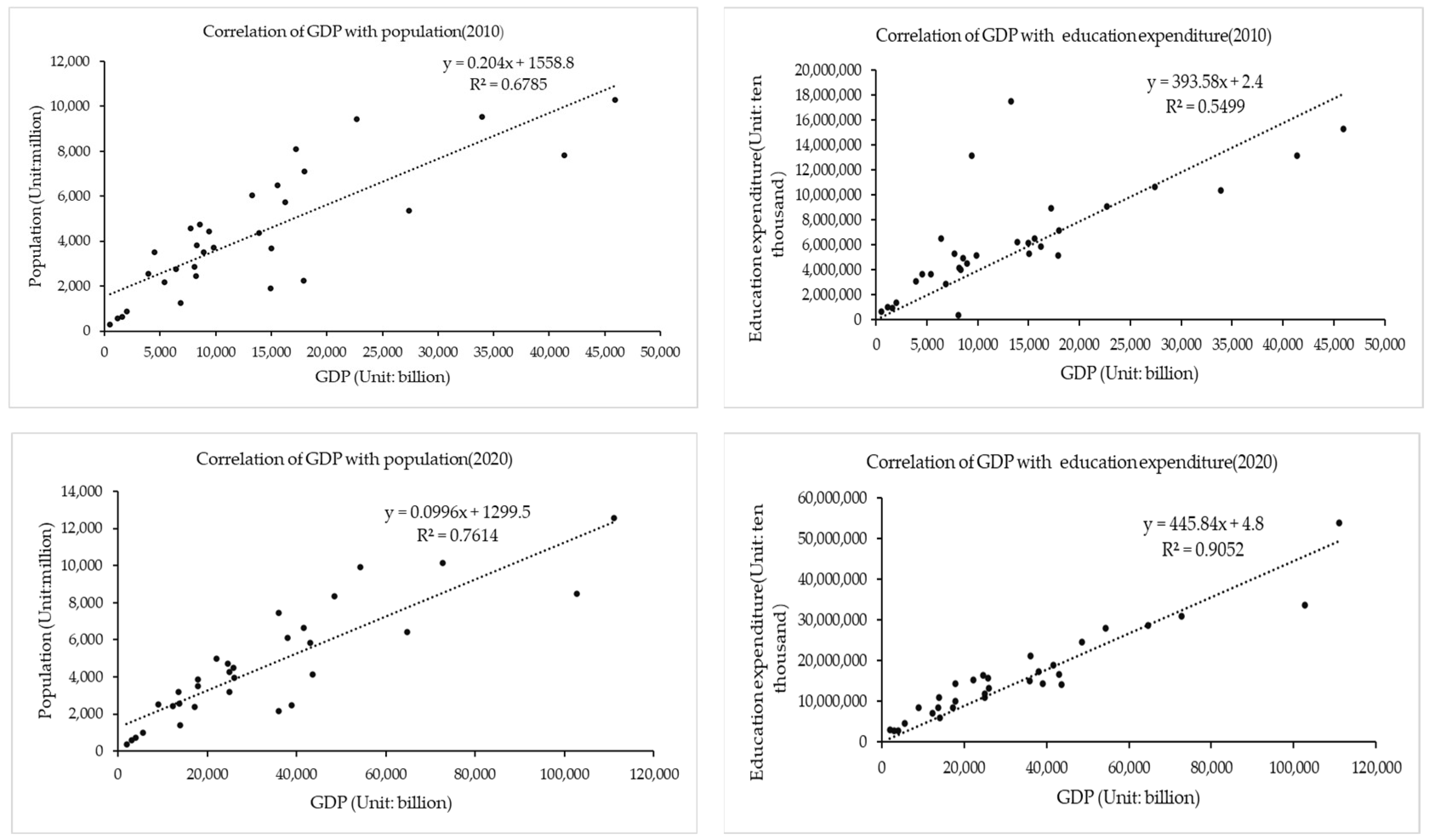

4.4. Influence of Regional Socio-Economics on the Number of Doctoral Disciplines in “Double First-Class” Universities

4.4.1. The Impact of Regional Socio-Economics on Top-Tier Education in the Region

4.4.2. The Impact of Regional Socio-Economics on Universities

5. Discussion

5.1. Spatial and Temporal Distribution Patterns of Doctoral Disciplines and Their Formation Mechanisms

5.2. The Mechanism of Regional Socio-Economic Influence on Top-Tier Education and Its Response

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, H.; He, A.; Wang, D. Reforming the doctoral degree authorization audit to promote the development of local high-level university. J. High. Educ. 2019, 40, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, M.; Wu, C. Logical roads and practice strategies of the talent cultivation in “double first-class” construction universities. Mod. Educ. Manag. 2023, 9, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Lu, Y. Scrutinizing and constructing world-class discipline construction: A case study based on the discipline of atmospheric science in Nanjing university of information engineering. Acad. Degrees Grad. Educ. 2020, 11, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y. Reflection and enlightenment on the “double first-class” construction in local universities. J. Henan Polytech. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 24, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Sun, J.; Lin, J. Experience and enlightenment of developing first-class disciplines in foreign entrepreneurial universities: Cases study based on Massachusetts institute of technology, Stanford university and university of Warwick. J. Hefei Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sc.) 2021, 5, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y. The distribution characteristics and attribution of degree points of higher education in China: A GIS-based method. Rev. High. Educ. 2020, 5, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Wu, Y. An analysis of features and factors of universities’ flagship disciplines in China. J. South China Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2014, 16, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. The evolution of the spatial distribution pattern of higher education institutions in China and its influencing factors. Jiangsu High. Educ. 2022, 12, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G. Building a system of higher education with Chinese characteristics: From the perspective of national strategy. China High. Educ. Res. 2020, 7, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J. Connotation and action framework of “double first-class” construction. Jiangsu High. Educ. 2016, 5, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Bi, X. On the connotation and characteristics of “double world-class” construction. Univ. Educ. Sci. 2017, 4, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H. The lineage, strategy and inspiration of international higher education spatial layout structure development. Educ. Career 2015, 25, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Hu, X. Research on influence of regional economy development on higher education based on panel data models. J. Univ. Sci. Technol. Liaoning 2009, 32, 488–493. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G. The evolution characteristics of China higher education spatial distribution and its development trends. J. High. Educ. 2019, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, G. Research on the Coordinated Development of Regional Economy and Higher Education. Ph.D. Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, L. Interaction mechanism and coupling strategy of higher education, scientific and technological innovation ability and regional economy. J. Natl. Acad. Educ. Adm. 2023, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, F. A re-recognition of the relationship between local higher education and socio-economic development. Jiangsu High. Educ. 2023, 3, 69–73+79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xin, Y.; Ni, H. On China’s higher education structure reform in the context of economic transformation and upgrading. Educ. Res. 2017, 38, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Wand, N. Trends of research topics on the relationship between higher education and regional economy—A cites pace-based visualized analysis. J. Hainan Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2020, 33, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, D. A study on the relationship between regional higher education development and regional economic development. Acad. Forum 2009, 4, 202–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. An analysis of the contradictory nature of the structure of postgraduate majors and regional economic development in China. High. Agric. Educ. 2014, 4, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ResearchGate. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234656539 (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Schultz, T. The Economic Value of Education; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Chellaraj, G.; Maskus, K.; Mattoo, A. The contribution of international graduate students to us innovation. Rev. Int. Econ. 2008, 16, 444–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippetti, A.; Archibugi, D. Innovation in times of crisis: National systems of innovation, structure, and demand. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, A.; Van Reenen, J. The economic impact of universities: Evidence from across the globe. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2019, 68, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, T.; Arano, K. The long-run economic impact of an institution of higher education: Estimating the human capital contribution. Econ. Dev. Q. 2016, 30, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emilia, C.; Dalina, D.; Ionela, C.; Iustina, B. The impact of higher education funding on socio-economic variables: Evidence from EU countries. J. Econ. Issues 2017, 3, 748–781. [Google Scholar]

- Rolf, K.; Maarten, H. How much does education matter and why? Eur. Soc. Rev. 2007, 23, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syeda, M.; Liu, Z. Exploring the relationships between socioeconomic indicators and student enrollment in higher education institutions of Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozza, C.; Divella, M. Human capital and firms’ innovation: Evidence from emerging economies. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2019, 28, 741–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez, I.; Livanos, I. Higher education and unemployment in Europe: An analysis of the academic subject and national effects. High. Educ. 2010, 59, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, Y. The role of postgraduate education in the innovation-driven promotion of economic growth. Educ. Res. 2021, 5, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Sun, Y. Can postgraduate education facilitate regional economic growth: Based on the penal data from 30 provincial-level regions. J. Grad. Educ. 2021, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Li, L. The impact of graduate education on economic growth in China: An empirical analysis on a provincial panel data from1996 to 2009. J. High. Educ. 2012, 33, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Du, F. Regional differences in the contribution rate of postgraduate education to economic growth and optimization of layout and structure. Educ. Dev. Res. 2020, 21, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y. Reflections on the organization of academics in the university. Tsinghua J. Educ. 2003, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Peng, Z. World-class universities’ disciplinary selection and distribution: Based on the 2015 QS university subject rankings. J. Soochow Univ. (Educ. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 3, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Disciplinary layout and strategic choices of the world’s top young universities—Discussion on the institutional space of the world-class discipline in the developing countries. China High. Educ. Res. 2017, 5, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Hu, J. Preponderant disciplines and world class universities: Evidences from Chinese and American top universities. China High. Educ. Res. 2013, 9, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, Y. An analysis of the optimization path of discipline layout for the construction of “double first-class”. China High. Educ. 2022, Z2, 54–56. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y.; Yuan, J. Textual analysis of “double first-class” construction programs in 28 provinces: The structural layout characteristics and development trend of first-class disciplines construction as an example. China Univ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wang, S.; Qie, H. The discipline layout and generation mechanism of China’s first-class university construction universities. Jiangsu High. Educ. 2018, 9, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wei, C. The macro-measurement and time-space difference of higher education quality: An empiric study with the data of Chinese university ranking. Educ. Econ. 2018, 34, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Kong, L. Driven dually by competition and planning: An optimization strategy in doctorate authorization programs structural layout of colleges and universities in western China. J. Kunming Univ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 20, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Wu, Y.; Fan, W.; Lei, Q. The research of doctorate degree authorization system in different regions and its trend --a longitudinal study based on data of 2005–2011. J. Natl. Acad. Educ. Adm. 2013, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2001/content_60854.htm (accessed on 25 June 2023).

- Ran, L. Development of Regional Higher Education: Historical Changes, Realistic Characteristics and Future Prospects—A Case Study of Shandong Province. Master’s Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. Study on the Provincial Difference of Educational Attainment and Influential Factors in China. Master’s Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.; Fan, M. Efficiency of higher education in China’s region and its development trend. Heilongjiang Res. High. Educ. 2013, 11, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/index.htm (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Menard, S. Applied Logistic Regression Analysis; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Vittinghoff, E.; Glidden, D.; Shiboski, S.; McCulloch, C. Regression Methods in Biostatistics: Linear, Logistic, Survival, and Repeated Measures Models; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gareth, J.; Daniela, W.; Trevor, H.; Robert, T. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Venables, W.; Ripley, B. Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Fang, C.; He, F. The impact of doctoral education on the economic growth—From the perspective of the regional differences in doctoral degree authorization. Educ. Res. 2022, 5, 124–138. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B. Thoughts on the regional differences of China’s graduate education. J. Xuzhou Inst. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.). 2012, 27, 93–97. [Google Scholar]

- Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-12/09/content_5730949.htm (accessed on 25 May 2023).

| Economic Division | Provinces | Number of Provinces |

|---|---|---|

| Eastern Region | Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, Guangdong, and Hainan | 10 |

| Central Region | Shanxi, Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei, and Hunan | 6 |

| Western Region | Inner Mongolia, Guangxi, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Tibet, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, and Xinjiang | 12 |

| Northeast Region | Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang | 3 |

| Economic Division | 1996 | 1998 | 2000 | 2003 | 2006 | 2011 | 2018 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | Average Annual Growth | Number of Provinces | Average Provincial Growth in the Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern region | 16 | 223 | 365 | 485 | 640 | 1163 | 1353 | 1400 | 1485 | 1518 | 57.8 | 10 | 5.8 |

| Central region | 3 | 44 | 78 | 121 | 177 | 348 | 435 | 452 | 478 | 483 | 18.5 | 6 | 3.1 |

| Western region | 2 | 46 | 86 | 120 | 161 | 341 | 438 | 446 | 477 | 489 | 18.7 | 12 | 1.6 |

| Northeast region | 2 | 29 | 52 | 70 | 101 | 183 | 210 | 214 | 223 | 225 | 8.6 | 3 | 2.9 |

| Economic Division | Province | 1996 | 1998 | 2000 | 2003 | 2006 | 2011 | 2018 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | Average Annual Growth | Number of “Double First-Class” Universities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern region | Beijing | 11 | 104 | 151 | 186 | 236 | 418 | 468 | 487 | 504 | 513 | 19.3 | 34 |

| Jiangsu | 0 | 31 | 60 | 84 | 110 | 212 | 247 | 251 | 271 | 275 | 10.6 | 16 | |

| Shanghai | 2 | 36 | 61 | 82 | 102 | 184 | 217 | 227 | 247 | 255 | 9.7 | 15 | |

| Guangdong | 0 | 14 | 22 | 40 | 56 | 107 | 141 | 146 | 159 | 166 | 6.4 | 8 | |

| Tianjin | 2 | 12 | 22 | 29 | 41 | 68 | 74 | 77 | 80 | 82 | 3.1 | 5 | |

| Shandong | 0 | 7 | 14 | 21 | 34 | 63 | 74 | 76 | 76 | 78 | 3.0 | 3 | |

| Zhejiang | 1 | 17 | 27 | 30 | 40 | 59 | 68 | 69 | 73 | 73 | 2.8 | 3 | |

| Fujian | 0 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 17 | 40 | 44 | 47 | 51 | 52 | 2.0 | 2 | |

| Hainan | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 13 | 13 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| Hebei | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 0.4 | 1 | |

| Central region | Hubei | 1 | 24 | 41 | 62 | 85 | 141 | 164 | 168 | 174 | 178 | 6.8 | 7 |

| Hunan | 1 | 11 | 20 | 34 | 46 | 94 | 116 | 125 | 128 | 128 | 4.9 | 5 | |

| Anhui | 1 | 9 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 48 | 58 | 60 | 66 | 67 | 2.5 | 3 | |

| Henan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 33 | 50 | 50 | 52 | 52 | 2.0 | 2 | |

| Shanxi | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 24 | 32 | 34 | 36 | 36 | 1.4 | 2 | |

| Jiangxi | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 15 | 15 | 22 | 22 | 0.8 | 1 | |

| Western region | Shaanxi | 2 | 24 | 40 | 53 | 71 | 125 | 142 | 147 | 156 | 159 | 6.0 | 8 |

| Sichuan | 0 | 15 | 29 | 39 | 55 | 96 | 114 | 114 | 121 | 125 | 4.8 | 8 | |

| Chongqing | 0 | 4 | 11 | 20 | 24 | 47 | 60 | 61 | 64 | 67 | 2.6 | 2 | |

| Gansu | 0 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 19 | 23 | 25 | 25 | 27 | 1.0 | 1 | |

| Xinjiang | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 22 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 0.9 | 2 | |

| Yunnan | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 13 | 21 | 21 | 22 | 22 | 0.8 | 1 | |

| Guangxi | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 17 | 17 | 19 | 19 | 0.7 | 1 | |

| Guizhou | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 17 | 17 | 19 | 19 | 0.7 | 1 | |

| Inner Mongolia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| Ningxia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 0.3 | 1 | |

| Qinghai | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 0.2 | 1 | |

| Tibet | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0.1 | 1 | |

| Northeast region | Jilin | 1 | 6 | 13 | 19 | 35 | 69 | 78 | 80 | 83 | 84 | 3.2 | 3 |

| Liaoning | 1 | 9 | 17 | 24 | 33 | 60 | 72 | 72 | 74 | 74 | 2.8 | 4 | |

| Heilongjiang | 0 | 14 | 22 | 27 | 33 | 54 | 60 | 62 | 66 | 67 | 2.6 | 4 | |

| National | 23 | 342 | 581 | 796 | 1079 | 2035 | 2436 | 2512 | 2663 | 2715 | 103.5 | 147 | |

| Economic Division | Province | Number of A-Class Disciplines | Number of “Double First-Class” Disciplines | Number of “Double First-Class” Universities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern region | Beijing | 185 | 127 | 34 |

| Shanghai | 86 | 65 | 15 | |

| Jiangsu | 74 | 48 | 16 | |

| Zhejiang | 42 | 23 | 3 | |

| Guangdong | 31 | 21 | 8 | |

| Tianjin | 30 | 14 | 5 | |

| Shandong | 14 | 8 | 3 | |

| Fujian | 9 | 7 | 2 | |

| Hainan | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Hebei | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Central region | Hubei | 49 | 32 | 7 |

| Hunan | 27 | 15 | 5 | |

| Anhui | 15 | 13 | 3 | |

| Jiangxi | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Henan | 0 | 4 | 2 | |

| Shanxi | 0 | 3 | 2 | |

| Western region | Sichuan | 28 | 15 | 8 |

| Shaanxi | 23 | 21 | 8 | |

| Chongqing | 7 | 5 | 2 | |

| Gansu | 2 | 4 | 1 | |

| Yunnan | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Guangxi | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Guizhou | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Inner Mongolia | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Ningxia | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Qinghai | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Tibet | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Xinjiang | 0 | 4 | 2 | |

| Northeast region | Heilongjiang | 21 | 12 | 4 |

| Jilin | 17 | 14 | 3 | |

| Liaoning | 11 | 8 | 4 | |

| National | 674 | 472 | 147 | |

| Total Number of Doctoral Disciplines (log) | Total Number of Doctoral Disciplines in Ministry-Affiliated Universities (log) | Total Number of Doctoral Disciplines in Local Universities (log) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2020 | 2010 | 2020 | 2010 | 2020 | |

| Population | 0.920 ***(0.208) | 0.797 **(0.149) | 0.970 ***(0.333) | 0.505 ***(0.163) | ||

| GDP | 0.845 ***(0.263) | |||||

| Literacy rate | 1.143 ***(0.208) | 0.877 ***(0.149) | 0.968 ***(0.263) | 1.385 ***(0.333) | 0.513 ***(0.163) | 0.331 (0.208) |

| Education expenditure | 0.426 **(0.208) | |||||

| Constant | 2.552 *** (0.200) | 3.763 *** (0.141) | 2.150 *** (0.256) | 2.647 *** (0.315) | 1.150 *** (0.157) | 2.465 *** (0.204) |

| Observation | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 |

| R2 | 0.597 | 0.639 | 0.495 | 0.426 | 0.367 | 0.182 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.569 | 0.613 | 0.459 | 0.385 | 0.321 | 0.124 |

| Residual std. Error (df = 28) | 1.113 | 0.787 | 1.427 | 1.752 | 0.872 | 1.136 |

| F statistic (df = 2;28) | 20.768 *** | 24.753 *** | 13.726 *** | 10.377 *** | 8.101 *** | 3.121 * |

| Average of Doctoral Disciplines Per Universities (log) | Average of Doctoral Disciplines in Ministry-Affiliated Universities (log) | Average of Doctoral Disciplines in Local Universities (log) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2020 | 2010 | 2020 | 2010 | 2020 | |

| GDP | −0.465 (0.345) | 0.565 **(0.209) | 0.697 **(0.260) | |||

| per capita GDP | −0.257 (0.169) | |||||

| Population | 0.482 ***(0.139) | 0.662 **(0.309) | 0.264 **(0.128) | |||

| Literacy rate | 0.390 ***(0.139) | 0.390 *(0.209) | 0.485 *(0.260) | 0.227 *(0.128) | ||

| Constant | 1.626 *** (0.134) | 2.786 *** (0.092) | 1.490 *** (0.204) | 1.973 *** (0.255) | 0.852 *** (0.123) | 2.110 *** (0.177) |

| Observation | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 |

| R2 | 0.372 | 0.281 | 0.305 | 0.285 | 0.181 | 0.000 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.327 | 0.201 | 0.256 | 0.234 | 0.122 | 0.000 |

| Residual std. Error | 0.744 (df = 28) | 0.514 (df = 27) | 1.136 (df = 28) | 1.421 (df = 28) | 0.684 (df = 28) | 0.985 (df = 28) |

| F statistic | 8.298 *** (df = 2;28) | 3.509 ** (df = 2;27) | 6.150 *** (df = 2;28) | 5.590 *** (df = 2;28) | 3.093 * (df = 2;28) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Yu, H.; Ding, M.; Shu, H. The Impact of Regional Socio-Economic Development on Spatial and Temporal Differences in the Distribution Pattern of Top-Tier Education in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15277. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115277

Chen X, Yu H, Ding M, Shu H. The Impact of Regional Socio-Economic Development on Spatial and Temporal Differences in the Distribution Pattern of Top-Tier Education in China. Sustainability. 2023; 15(21):15277. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115277

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xiaoshuang, Hao Yu, Mingli Ding, and Huisheng Shu. 2023. "The Impact of Regional Socio-Economic Development on Spatial and Temporal Differences in the Distribution Pattern of Top-Tier Education in China" Sustainability 15, no. 21: 15277. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115277

APA StyleChen, X., Yu, H., Ding, M., & Shu, H. (2023). The Impact of Regional Socio-Economic Development on Spatial and Temporal Differences in the Distribution Pattern of Top-Tier Education in China. Sustainability, 15(21), 15277. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115277