Tourism and Environment: Ecology, Management, Economics, Climate, Health, and Politics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

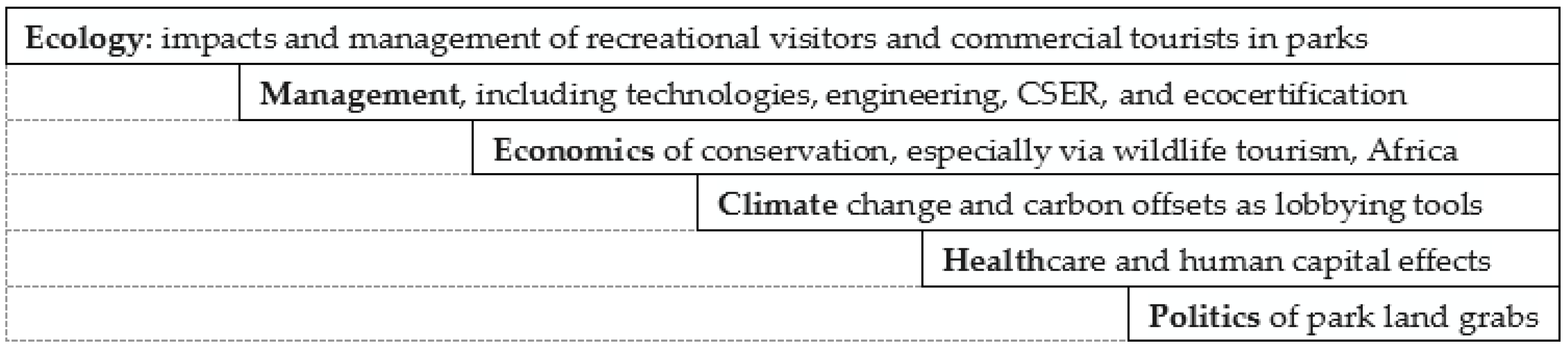

- Ecology: of recreation and park visitor impacts.

- Management: of wastes and resources, advertised via ecolabels.

- Economics: of contributions to conservation by some tourism enterprises, principally through private reserves and park funding.

- Climate: consequences of travel and tourism for climate change, and lobbying and marketing measures to maintain tourism income.

- Health: psychology and economics of tourism’s contribution to mental health and human capital.

- Politics: efforts by tourism advocates to gain control of parks and protected areas, to profit from preferential access to public resources.

2. Ecology of Park Visitor Impacts

3. Management and CSER

4. Economics of Conservation

5. Climate Change and Carbon Offsets

6. Health and Human Capital

7. Political Land Grabs

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buckley, R.C. Sustainable tourism: Research and reality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.; Silva, L.F.; Vieira, A. Protected areas and nature-based tourism: A 30-year bibliometric review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, A.S. Wildlife Management in the National Parks; US National Park Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1963.

- Herrero, S. Human injury inflicted by grizzly bears: The chance of human injury in the national parks can be reduced to a minimum through improved management. Science 1970, 170, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, R.; Nilsen, P.; Payne, R.J. Visitor management in Canadian national parks. Tour. Manag. 1988, 9, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackley, M. Visitor Management; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle, M. Recreation Ecology; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R.C. Tourism and environment. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2011, 36, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggenbuck, J.W.; Williams, D.R.; Watson, A.E. Defining acceptable conditions in wilderness. Environ. Manag. 1993, 17, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marco, M.; Ferrier, S.; Harwood, T.D.; Hoskins, A.J.; Watson, J.E. Wilderness areas halve the extinction risk of terrestrial biodiversity. Nature 2019, 573, 582–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, N.E.; McManus Chauvin, K.; Skybrook, D.; Barnosky, A.D. Including stewardship in ecosystem health assessment. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monz, C.A.; Pickering, C.M.; Hadwen, W.L. Recent advances in recreation ecology and the implications of different relationships between recreation uise and ecological impacts. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2013, 11, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.; McGinlay, J.; Jones, A.; Malesios, C.; Holtvoeth, J.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G.; Gkoumas, V.; Kontoleon, A. COVID-19 and protected areas: Impacts, conflicts, and possible management solutions. Conserv. Lett. 2021, 14, e12800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, E.S. Sewage pollution from tourist hotels in Jamaica. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1973, 4, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGeorges, A.; Goreau, T.J.; Reilly, B. Land-sourced pollution with an emphasis on domestic sewage: Lessons from the Caribbean and implications for coastal development on Indian Ocean and Pacific coral reefs. Sustainability 2010, 2, 2919–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, J.; Maar, M.; Rasmussen, M.L.; Hansen, L.B.; Hamad, I.Y.; Stæhr, P.A.U. High-resolution hydrodynamics of coral reefs and tracing of pollutants from hotel areas along the west coast of Unguja Island, Zanzibar. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 191, 114968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, A. Environment and Tourism; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Gossling, S.; Scott, D. (Eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mensah, I. Environmental Management Concepts & Practices for the Hospitality Industry; Cambridge Scholars: Newcastle, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Huddart, D.; Stott, T. Adventure Tourism: Environmental Impacts and Management; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Hall, C.M.; Esfandiar, K.; Seyfi, S. A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the sustainable development goals. J. Sust. Tour. 2023, 31, 1497–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Lee, S. Effects of different dimensions of corporate social responsibility on corporate financial performance in tourism-related industries. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.H.; Habibullah, M.S.; Tan, S.K.; Choon, S.W. The impact of the dimensions of environmental performance on firm performance in travel and tourism industry. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 203, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbaugh, R.; Maxwell, J.W.; Roussillon, B. Label confusion: The Groucho effect of uncertain standards. Manag. Sci. 2011, 57, 1512–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.C. Sector-scale proliferation of CSR quality label programs via mimicry: The rotkäppchen effect. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, M.P. Economic Perspectives on Nature Tourism, Conservation and Development; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, D.B.; Lawton, L.J. Twenty years on: The state of contemporary ecotourism research. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1168–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budowski, G. Tourism and environmental conservation: Conflict, coexistence, or symbiosis? Environ. Conserv. 1976, 3, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.C. Tourism and natural World Heritage: A complicated relationship. J. Trav. Res. 2018, 57, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.C.; Morrison, C.F.; Castley, J.G. Net effects of ecotourism on threatened species survival. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrianambinina, F.O.D.; Schuurman, D.; Rakotoarijaona, M.A.; Razanajovy, C.N.; Ramparany, H.M.; Rafanoharana, S.C.; Rasamuel, H.A.; Faragher, K.D.; Waeber, P.O.; Wilmé, L. Boost the resilience of protected areas to shocks by reducing their dependency on tourism. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0278591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Zhu, H.; Bhammar, H.; Earley, E.; Filipski, M.; Narain, U.; Spencer, P.; Whitney, E.; Taylor, J.E. Economic impact of nature-based tourism. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.; Pearson, J.; Arbieu, U.; Riechers, M.; Thomsen, S.; Martín-López, B. Tourists’ valuation of nature in protected areas: A systematic review. Ambio 2023, 52, 1065–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G.; Harrison, R.; Kinnaird, V.; McBoyle, G.; Quinlan, C. The implications of climatic change for camping in Ontario. Recreat. Res. Rev. 1986, 13, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K. Tourism and climate change. Land Use Policy 1990, 7, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, D.; Butler, R. Towards sustainable tourism. Tour. Manag. 1990, 11, 263–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Wall, G.; McBoyle, G. The evolution of the climate change issue in the tourism sector. In Tourism, Recreation and Climate Change; Hall, C.M., Higham, J., Eds.; Channel View: Bristol, UK, 2005; Volume 22, pp. 44–60. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, S.; Balas, M.; Mayer, M.; Sun, Y.Y. A review of tourism and climate change mitigation: The scales, scopes, stakeholders and strategies of carbon management. Tour. Manag. 2023, 95, 104681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Humpe, A.; Sun, Y.Y. On track to net-zero? Large tourism enterprises and climate change. Tour. Manag. 2024, 100, 104842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, B.; Mousavian, M. Carbon Capture to Serve Enhanced Oil Recovery: Overpromise and Underperformance. 2022. Available online: https://ieefa.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Carbon-Capture-to-Serve-Enhanced-Oil-Recovery-Overpromise-and-Underperformance_March-2022.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Allied Offsets. Carbon Dioxide Removal Report. 2023. Available online: https://alliedoffsets.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Allied_Offsets_CDR_Report_FINAL_June-2023-2.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Devillers, E.; Lyons, K. Green Colonialism 2.0: Tree Plantations and Carbon Offsets in Africa. 2023. Available online: https://www.oaklandinstitute.org/sites/oaklandinstitute.org/files/green-colonialism.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Lakhani, N. Top Carbon Offset Projects May Not Cut Planet-Heating Emissions. 2023. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/sep/19/do-carbon-credit-reduce-emissions-greenhouse-gases (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Stapp, J.; Nolte, C.; Potts, M.; Baumann, M.; Haya, B.K.; Butsic, V. Little evidence of management change in California’s forest offset program. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, B. Regulators vs Science: Why Mulga Exposes Our Carbon Credits System As a Rort. 2023. Available online: https://www.crikey.com.au/2023/09/25/carbon-credits-system-mulga-exposes-rort/ (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Pasini, W. Tourist health as a new branch of public health. World Health Stat. Quart 1989, 42, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, P.L.; Stringer, P.F. Psychology and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1991, 18, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.K.; Diekmann, A. Tourism and wellbeing. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 66, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.C. Tourism and mental health: Foundations, frameworks, and futures. J. Trav. Res. 2023, 62, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.C.; Chauvenet, A.L.M. Economic value of nature via healthcare savings and productivity increases. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 272, 109665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coventry, P.A.; Brown, J.E.; Pervin, J.; Brabyn, S.; Pateman, R.; Breedvelt, J.; Gilbody, S.; Stancliffe, R.; McEachan, R.; White, P.L. Nature-based outdoor activities for mental and physical health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Soc. Med. Popul. Health 2021, 16, 100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derose, K.P.; Wallace, D.D.; Han, B.; Cohen, D.A. Effects of park-based interventions on health-related outcomes: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2021, 147, 106528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.Y.; Astell-Burt, T.; Rahimi-Ardabili, H.; Feng, X.Q. Effect of nature prescriptions on cardiometabolic and mental health, and physical activity: A systematic review. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e313–e328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins-Martin, K.; Bolanis, D.; Richard-Devantoy, S.; Pennestri, M.H.; Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C.; Philippe, F.; Guindon, J.; Gouin, J.P.; Ouellet-Morin, I.; Geoffroy, M.C. The effects of walking in nature on negative and positive affect in adult psychiatric outpatients with major depressive disorder: A randomized-controlled study. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 318, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Elliott, L.R.; Grellier, J.; Economou, T.; Bell, S.; Bratman, G.N.; Cirach, M.; Gascon, M.; Lima, M.L.; Lõhmus, M.; et al. Associations between green/blue spaces and mental health across 18 countries. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeon, P.S.; Jeon, J.Y.; Jung, M.S.; Min, G.M.; Kim, G.Y.; Han, K.M.; Shin, M.J.; Jo, S.H.; Kim, J.G.; Shin, W.S. Effect of forest therapy on depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meidenbauer, K.L.; Stenfors, C.U.; Bratman, G.N.; Gross, J.J.; Schertz, K.E.; Choe, K.W.; Berman, M.G. The affective benefits of nature exposure: What’s nature got to do with it? J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 72, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Sha, J.; Scott, N. Restoration of visitors through nature-based tourism: A systematic review, conceptual framework, and future research directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Smale, B.; Xiao, H. Examining the change in wellbeing following a holiday. Tour. Manag. 2021, 87, 104367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gump, B.B.; Hruska, B.; Pressman, S.D.; Park, A.; Bendinskas, K.G. Vacation’s lingering benefits, but only for those with low stress jobs. Psychol. Health 2021, 36, 895–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, R.C.; Zhong, L.S.; Cooper, M.A. Mental health and nature: More implementation research needed. Nature 2022, 612, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneguzzo, F.; Albanese, L.; Antonelli, M.; Baraldi, R.; Becheri, F.R.; Centritto, F.; Donelli, D.; Finelli, F.; Firenzuoli, F.; Margheritini, G.; et al. Short-term effects of forest therapy on mood states: A pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astell-Burt, T.; Pappas, E.; Redfern, J.; Feng, X.Q. Nature prescriptions for community and planetary health: Unrealised potential to improve compliance and outcomes in physiotherapy. J. Physiother. 2022, 68, 151–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M.C.; Oyekanmi, K.O.; Gibson, A.; South, E.C.; Bocarro, J.; Hipp, J.A. Nature prescriptions for health: A review of evidence and research opportunities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakadai, R. Macroecological processes drive spiritual ecosystem services obtained from giant trees. Nat. Plants 2023, 9, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stobbe, E.; Sunderman, J.; Ascone, L.; Kühn, S. Birdsongs alleviate anxiety and paranoia in healthy participants. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammoud, R.; Tognin, S.; Burgess, L.; Bergou, N.; Smythe, M.; Gibbons, J.; Davidson, N.; Afifi, A.; Bakolis, I.; Mecehlli, A. Smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment reveals mental health benefits of birdlife. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.G.; Shin, W.S. Forest therapy alone or with a guide: Is there a difference between self-guided forest therapy and guided forest therapy programs? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, G.; Ding, L.; Xiang, K.; Prideaux, B.; Xu, J. Understanding the value of tourism to seniors’ health and positive aging. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragan-Jason, G.; de Mazancourt, C.; Parmesan, C.; Singer, M.C.; Loreau, M. Human-nature connectedness as a pathway to sustainability: A global meta-analysis. Conserv. Lett. 2022, 15, e12852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selinske, M.J.; Harrison, L.; Simmons, B.A. Examining connection to nature at multiple scales provides insights for urban conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 280, 109984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, U.; Balvanera, P.; Anderson, C.B.; Chaplin-Kramer, R.; Christie, M.; González-Jiménez, D.; Martin, A.; Raymond, C.M.; Termansen, M.; Vatn, A.; et al. Diverse values of nature for sustainability. Nature 2023, 620, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Ma, J. From nature experience to visitors’ pro-environmental behavior: The role of perceived restorativeness and well-being. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.O.; Mai, K.M.; Park, S. Green space accessibility helps buffer declined mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from big data in the United Kingdom. Nat. Ment. Health 2023, 1, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, W.J.; Badenhorst, C.E.; Draper, N.; Basu, A.; Elliot, C.A.; Hamlin, M.J.; Batten, J.; Lambrick, D.; Faulkner, J. Physical activity, mental health and wellbeing during the first COVID-19 containment in New Zealand: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauls, L.A.; Devine, J.A. Geospatial technologies in tourism land and resource grabs: Evidence from Guatemala’s protected areas. In Routledge Handbook of Global Land and Resource Grabbing; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2023; pp. 205–219. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R.C.; Underdahl, S.; Chauvenet, A.L.M. Problems, politics and pressures for parks agency budgets in Australia. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 274, 109723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, C.; Ward, M.; Watson, J.E.; Reside, A.E.; van Leeuwen, S.; Legge, S.; Geary, W.L.; Lintermans, M.; Kennard, M.J.; Stuart, S.; et al. The costs of managing key threats to Australia’s biodiversity. J. Appl. Ecol. 2023, 60, 898–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bouille, D.; Fargione, J.; Armsworth, P.R. The cost of buying land for protected areas in the United States. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 284, 110138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.C.; Underdahl, S.; Chauvenet, A.L.M. COP15: Escalating tourism threat to park conservation. Nature 2023, 613, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Li, Y.; Feng, Y.; Hua, F.; Shen, X.; Li, S.; Shrestha, N.; Peng, S.; Rahbek, C.; Wang, Z. Anthropogenic vulnerability assessment of global terrestrial protected areas with a new framework. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 283, 110064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkins, A.T.; Beresford, A.E.; Buchanan, G.M.; Crowe, O.; Elliott, W.; Izquierdo, P.; Patterson, D.J.; Butchart, S.H. A global assessment of the prevalence of current and potential future infrastructure in Key Biodiversity Areas. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 281, 109953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hougie, D.J.P.; Dickinson, J.E. The right to roam–what’s in a name? Policy development and terminology issues in England and Wales, UK. Eur. Environ. 2000, 10, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, R. Salter Brothers Acquires Spicers Retreats for Estimated $130 Million. 2022. Available online: https://www.hotelmanagement.com.au/2022/12/20/salter-brothers-acquires-spicers-retreats-for-estimated-130-million/ (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- WTTC. Membership. 2023. Available online: https://wttc.org/membership/our-members (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Coulton, A. Intrepid Invests $7.85 Million in CABN to Promote Off-the-Grid Experiences. 2022. Available online: https://www.travelweekly.com.au/article/intrepid-invests-7-85-million-in-cabn-to-promote-off-the-grid-experiences/ (accessed on 19 October 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buckley, R.C.; Underdahl, S. Tourism and Environment: Ecology, Management, Economics, Climate, Health, and Politics. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15416. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115416

Buckley RC, Underdahl S. Tourism and Environment: Ecology, Management, Economics, Climate, Health, and Politics. Sustainability. 2023; 15(21):15416. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115416

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuckley, Ralf C., and Sonya Underdahl. 2023. "Tourism and Environment: Ecology, Management, Economics, Climate, Health, and Politics" Sustainability 15, no. 21: 15416. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115416

APA StyleBuckley, R. C., & Underdahl, S. (2023). Tourism and Environment: Ecology, Management, Economics, Climate, Health, and Politics. Sustainability, 15(21), 15416. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115416