The Often-Forgotten Innovation to Improve Sustainability: Assessing Food and Agricultural Sciences Curricula as Interventions in Uganda

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Discern actors’ reactions to the extent to which food and agricultural sciences curricula could be implemented in the GPP;

- Investigate actors’ existing food and agricultural sciences programmatic instructional needs in developing, implementing, and evaluating curricula in the GPP.

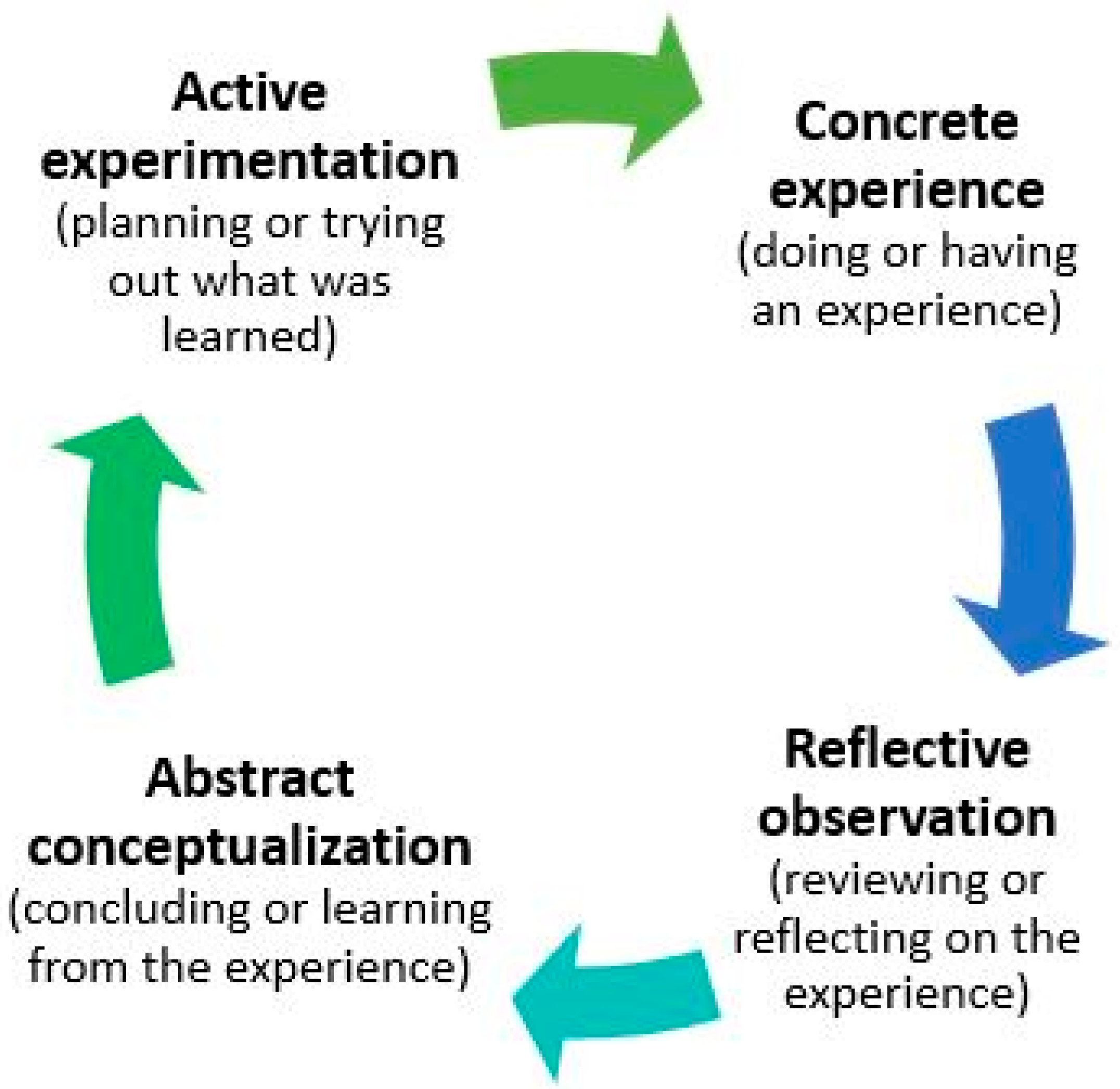

2. Conceptual Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Sample

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Trustworthiness

4. Results

4.1. KASAs—Skills

4.2. KASAs—Attitudes

4.3. KASAs—Aspirations

4.4. Resources

4.5. Activities

4.6. KASAs

4.7. Practices

4.8. SEE Outcomes

4.9. Resources

4.10. KASAs

4.11. Practices

4.12. SEE Outcomes

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scarborough, W.J.; Sin, R.; Risman, B. Attitudes and the Stalled Gender Revolution: Egalitarianism, Traditionalism, and Ambivalence from 1977 through 2016. Gend. Soc. 2018, 33, 173–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The 17 Goals. 2019. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Nassani, A.A.; Aldakhil, A.M.; Abro, M.M.Q.; Islam, T.; Zaman, K. The impact of tourism and finance on women empowerment. J. Policy Model. 2018, 41, 234–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndagurwa, P.; Chemhaka, G.B. Education elasticities of young women fertility in sub-Saharan Africa: Insights from Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe. Dev. S. Afr. 2020, 37, 921–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjengwa, J.; Matema, C.; Tirivanhu, D.; Tizora, R. Deprivation among children living and working on the streets of Harare. Dev. S. Afr. 2016, 33, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gikunda, R.M.; Ooga, D.M.; Okiamba, I.N.; Anyuor, S. Cultural barriers towards women and youth entry to apiculture production in Maara Sub-County, Kenya. Adv. Agric. Dev. 2021, 2, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukundane, C.; Zeelen, J.; Minnaert, A.; Kanyandago, P. ‘I felt very bad, I had self-rejection’: Narratives of exclusion and marginalisation among early school leavers in Uganda. J. Youth Stud. 2013, 17, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denov, M.; Piolanti, A. Identity formation and change in children and youth born of wartime sexual violence in northern Uganda. J. Youth Stud. 2020, 24, 1135–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Oshri, A.; Liu, S.; Smith, E.P.; Kogan, S.M. Child Maltreatment and Resilience: The Promotive and Protective Role of Future Orientation. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 2075–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agole, D.; Yoder, E.; Brennan, M.A.; Baggett, C.; Ewing, J.; Beckman, M.; Matsiko, F.B. Determinants of cohesion in smallholder farmer groups in Uganda. Adv. Agric. Dev. 2021, 2, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Grebmer, K.; Bernstein, J.; Wiemers, M.; Schiffer, T.; Hanano, A.; Towey, O.; Chéilleachair, R.N.; Foley, C.; Gitter, S.; Ekstrom, K.; et al. 2021 Global Hunger Index: Hunger and Food Systems in Conflict Settings. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. 2021. Available online: https://www.globalhungerindex.org/pdf/en/2021.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- World Food Programme. Uganda. 2023. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/countries/uganda (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Mubiru, D.N.; Radeny, M.; Kyazze, F.B.; Zziwa, A.; Lwasa, J.; Kinyangi, J.; Mungai, C. Climate trends, risks and coping strategies in smallholder farming systems in Uganda. Clim. Risk Manag. 2018, 22, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronner, E.; Descheemaeker, K.; Almekinders, C.; Ebanyat, P.; Giller, K. Co-design of improved climbing bean production practices for smallholder farmers in the highlands of Uganda. Agric. Syst. 2019, 175, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssebunya, B.R.; Schader, C.; Baumgart, L.; Landert, J.; Altenbuchner, C.; Schmid, E.; Stolze, M. Sustainability Performance of Certified and Non-certified Smallholder Coffee Farms in Uganda. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 156, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Campenhout, B.; Spielman, D.J.; Lecoutere, E. Information and Communication Technologies to Provide Agricultural Advice to Smallholder Farmers: Experimental Evidence from Uganda. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 103, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, R.; Sprayberry, S.; Dooley, K.; Ahn, J.; Richards, J.; Kinsella, J.; Lee, C.-L.; Ray, N.; Cardey, S.; Benson, C.; et al. Sustaining Global Food Systems with Youth Digital Livestock Production Curricula Interventions and Adoption to Professionally Develop Agents of Change. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, L.; Ballard, H.; Harris, E.; Scow, K. Seeing below the surface: Making soil processes visible to Ugandan smallholder farmers through a constructivist and experiential extension approach. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 35, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukahirwa, L.; Mugisha, A.; Kyewalabye, E.; Nsibirano, R.; Kabahango, P.; Kusiimakwe, D.; Mugabi, K.; Bikaako, W.; Miller, B.; Bagnol, B.; et al. Women smallholder farmers' engagement in the vaccine chain in Sembabule District, Uganda: Barriers and Opportunities. Dev. Pract. 2022, 33, 416–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E.; Isgren, E. Gambling in the garden: Pesticide use and risk exposure in Ugandan smallholder farming. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 82, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabuuma, D.; Ekesa, B.; Faber, M.; Mbhenyane, X. Community perspectives on food security and dietary diversity among rural smallholder farmers: A qualitative study in central Uganda. J. Agric. Food Res. 2021, 5, 100183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aseete, P.; Barkley, A.; Katungi, E.; Ugen, M.A.; Birachi, E. Public–private partnership generates economic benefits to smallholder bean growers in Uganda. Food Secur. 2022, 15, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiputwa, B.; Qaim, M. Sustainability Standards, Gender, and Nutrition among Smallholder Farmers in Uganda. J. Dev. Stud. 2016, 52, 1241–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiru, I.O.; Aluko, B.; Adejumo, A.A. Teachers’ Perception of the Effects of the New Education Curriculum on the Choice of Agriculture as a Career Among Secondary School Students in Oyo State. J. Agric. Food Inf. 2018, 20, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauke, P.K.; Kabiti, H.M. Teachers’ Perceptions on Agricultural Science Curriculum Evolvement, Infrastructure Provision and Quality Enhancement in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Int. J. Educ. Sci. 2016, 14, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.H.; Ibrahim, O.A.; Agunbiade, M.W. Integrating Climate Change and Smart Agriculture Contents into Nigerian School Curriculum. Indones. J. Curric. Educ. Technol. Stud. 2022, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbo, B.N.; Nwaokocha, P.O.; Ifeanyieze, F.O. Curriculum Reforms in Agricultural Trades of Secondary Schools for Corruption Free Society. Niger. J. Curri. Stud. 2021, 27, 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Mukembo, S.C.; Edwards, M.C. Improving Livelihoods through Youth-Adult Partnerships involving School-based, Agripreneurship Projects: The Experiences of Adult Partners in Uganda. J. Int. Agric. Ext. Educ. 2020, 27, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukembo, S.C.; Edwards, M.C.; Robinson, J.S. Comparative Analysis of Students’ Perceived Agripreneurship Competencies and Likelihood to become Agripreneurs depending on Learning Approach: A Report from Uganda. J. Agric. Educ. 2020, 61, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-L.; Strong, R.; Briers, G.; Murphrey, T.; Rajan, N.; Rampold, S. A Correlational Study of Two U.S. State Extension Professionals’ Behavioral Intentions to Improve Sustainable Food Chains through Precision Farming Practices. Foods 2023, 12, 2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just Like My Child Foundation. Our History. 2023. Available online: https://www.justlikemychild.org/our-history-as-uganda-page/ (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Cai, W.; Wang, R.; Zhang, S. Efficient food systems for greater sustainability. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, L.; Piña, M.; Hamie, S.; Davis, T. Community-level impact of a female empowerment program in Uganda. J. Univer. Glob. Ed. Issues 2020, 6, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Qian, Y. Gender, education expansion and intergenerational educational mobility around the world. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2023, 7, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-13-389240-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1984; Volume 1, ISBN 0132952610. [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell, S.K.; Albrecht, J.A.; Nugent, G.C.; Kunz, G.M. Using Targeting Outcomes of Programs as a Framework to Target Photographic Events in Nonformal Educational Programs. Am. J. Eval. 2011, 33, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockwell, S.K.; Bennett, C. Targeting Outcomes of Programs: A Hierarchy a Hierarchy for Targeting Outcomes and Evaluating Their Achievement. University of Nebraska. 2004. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1047&context=aglecfacpub (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- Baú, V. Art, Development and Peace Working with Adolescents Living in Internally Displaced People's Camps in Mindanao. J. Int. Dev. 2017, 29, 948–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, A.H.; Sood, S.; Robichaud, M. Participatory Methods for Entertainment–Education: Analysis of Best Practices. J. Creat. Commun. 2017, 12, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C. Up the hierarchy. J. Ext. 1975, 13, 7–12. Available online: http://www.joe.org/joe/1975march/75-2-a1.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Radhakrishna, R.; Bowen, C.F. Viewing Bennett’s Hierarchy from a Different Lens: Implications for Extension Program Evaluation. J. Ext. 2010, 48, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Dart, J.; Davies, R. A Dialogical, Story-Based Evaluation Tool: The Most Significant Change Technique. Am. J. Eval. 2003, 24, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, B.; Rogers, P.; Kefford, B. Teaching People to Fish? Building the Evaluation Capability of Public Sector Organizations. Evaluation 2003, 9, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, I.; Lee, J. The effects of learner factors on MOOC learning outcomes and their pathways. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2019, 57, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.J.; Terhorst, A.; Kang, B.H. From Data to Decisions: Helping Crop Producers Build Their Actionable Knowledge. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2017, 36, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cliffe, N.; Stone, R.; Coutts, J.; Reardon-Smith, K.; Mushtaq, S. Developing the capacity of farmers to understand and apply seasonal climate forecasts through collaborative learning processes. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2016, 22, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douthwaite, B.; Alvarez, S.; Thiele, G.; Mackay, R. Participatory Impact Pathways Analysis: A Practical Method for Project Planning and Evaluation. Institutional Learning and Change ILAC 1–4. 2008. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/70093 (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, S.; Cresswell, K.; Robertson, A.; Huby, G.; Avery, A.; Sheikh, A. The case study approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazan, B. Three Approaches to Case Study Methods in Education: Yin, Merriam, and Stake. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, E.W. Generalizing from Research Findings: The Merits of Case Studies. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundill, G.; Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Mukute, M.; Belay, M.; Shackleton, S.; Kulundu, I. A reflection on the use of case studies as a methodology for social learning research in sub Saharan Africa. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2014, 69, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefenbach, T. Are case studies more than sophisticated storytelling? Methodological problems of qualitative empirical research mainly based on semi-structured interviews. Qual. Quant. 2008, 43, 875–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Dai, Y.; Dong, X. The enabling mechanism of shuren culture in ICT4D: A case study of rural China. Technol. Soc. 2021, 68, 101842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinngrebe, Y.; Borasino, E.; Chiputwa, B.; Dobie, P.; Garcia, E.; Gassner, A.; Kihumuro, P.; Komarudin, H.; Liswanti, N.; Makui, P.; et al. Agroforestry governance for operationalising the landscape approach: Connecting conservation and farming actors. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 1417–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cicco-Bloom, B.; Crabtree, B. The qualitative research interview. Med. Educ. 2006, 40, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masika, R. Mobile Phones and Entrepreneurial Identity Negotiation by Urban Female Street Traders in Uganda. Gend. Work. Organ. 2017, 24, 610–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel-Villarreal, R.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E.L.; Hingley, M. Exploring producers’ motivations and challenges within a farmers’ market. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 2089–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J. Are farmers in England equipped to meet the knowledge challenge of sustainable soil management? An analysis of farmer and advisor views. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 86, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agir, S.; Derin-Gure, P.; Senturk, B. Farmers’ perspectives on challenges and opportunities of agrivoltaics in Turkiye: An institutional perspective. Renew. Energy 2023, 212, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, A.; Burger, P. Understanding diversity in farmers’ routinized crop protection practices. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 89, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalsveen, K.; Ingram, J.; Urquhart, J. The role of farmers’ social networks in the implementation of no-till farming practices. Agri. Syst. 2020, 181, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollstedt, M.; Rezat, S. An Introduction to Grounded Theory with a Special Focus on Axial Coding and the Coding Paradigm; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine de Gruyter: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Questions | Research Objective |

|---|---|

| What agricultural sustainability knowledge did you acquire from the GPP? | #1. Discern actors’ reactions to the extent to which food and agricultural sciences curricula could be implemented in the GPP. |

| Did your agricultural sustainability attitudes change from your GPP participation? If so, please explain. | |

| What agricultural sustainability skills did you acquire from the GPP? | |

| Did you gain agricultural sustainability aspirations from your GPP participation? If so, please explain. | |

| If food and agricultural sciences curricula were a permanent feature of the GPP, what resources would a teacher need to be successful? | #2. Investigate actors’ existing food and agricultural sciences programmatic instructional needs in developing, implementing, and evaluating curricula in GPP. |

| Questions/Items | f | % |

|---|---|---|

| Objective 1 | ||

| Did your agricultural sustainability attitudes change from your GPP participation? If so, please explain. | 61 | 49.40 |

| What agricultural sustainability skills did you acquire from the GPP? | 101 | 79.53 |

| Did you gain agricultural sustainability aspirations from your GPP participation? If so, please explain. | 97 | 76.37 |

| Objective 2 | ||

| If food and agricultural sciences curricula were a permanent feature of the GPP, what resources would a teacher need to be successful? | ||

| Resources | 93 | 73.22 |

| Activities | 67 | 54.47 |

| KASAs | 72 | 58.53 |

| Practices | 112 | 88.18 |

| SEE Outcomes | 78 | 61.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Strong, R.; Baker, M.; Dooley, K.; Ray, N. The Often-Forgotten Innovation to Improve Sustainability: Assessing Food and Agricultural Sciences Curricula as Interventions in Uganda. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15461. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115461

Strong R, Baker M, Dooley K, Ray N. The Often-Forgotten Innovation to Improve Sustainability: Assessing Food and Agricultural Sciences Curricula as Interventions in Uganda. Sustainability. 2023; 15(21):15461. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115461

Chicago/Turabian StyleStrong, Robert, Mitchell Baker, Kim Dooley, and Nicole Ray. 2023. "The Often-Forgotten Innovation to Improve Sustainability: Assessing Food and Agricultural Sciences Curricula as Interventions in Uganda" Sustainability 15, no. 21: 15461. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115461

APA StyleStrong, R., Baker, M., Dooley, K., & Ray, N. (2023). The Often-Forgotten Innovation to Improve Sustainability: Assessing Food and Agricultural Sciences Curricula as Interventions in Uganda. Sustainability, 15(21), 15461. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115461