A Bibliometric Analysis on Cooperatives in Circular Economy and Eco-Innovation Studies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Cooperative Enterprises and Environmental Sustainability

3. Methodology

3.1. Thematic Analysis Using Scopus and Manual Review

3.2. Bibliometric Analysis Using WoS and Biblioshiny

4. Results

4.1. Thematic Analysis

4.1.1. Cooperatives and CE

4.1.2. Cooperatives and EI

4.2. Bibliometric Analysis (WoS Data Set and Biblioshiny with R Studio; N = 101)

4.3. Motor Themes (Clusters) of Cooperatives Research Focusing on CE and EI

4.3.1. CE Principles (Brown Cluster): Industrial Ecology & Cradle-to-Cradle

4.3.2. Material Recovery (Pink Cluster): Recycling, Waste Pickers, and by Products

4.3.3. Material Management (Green Cluster): Waste Management, Governance, and Municipal Solid Waste

4.4. Relationship between Clusters

5. Conclusions

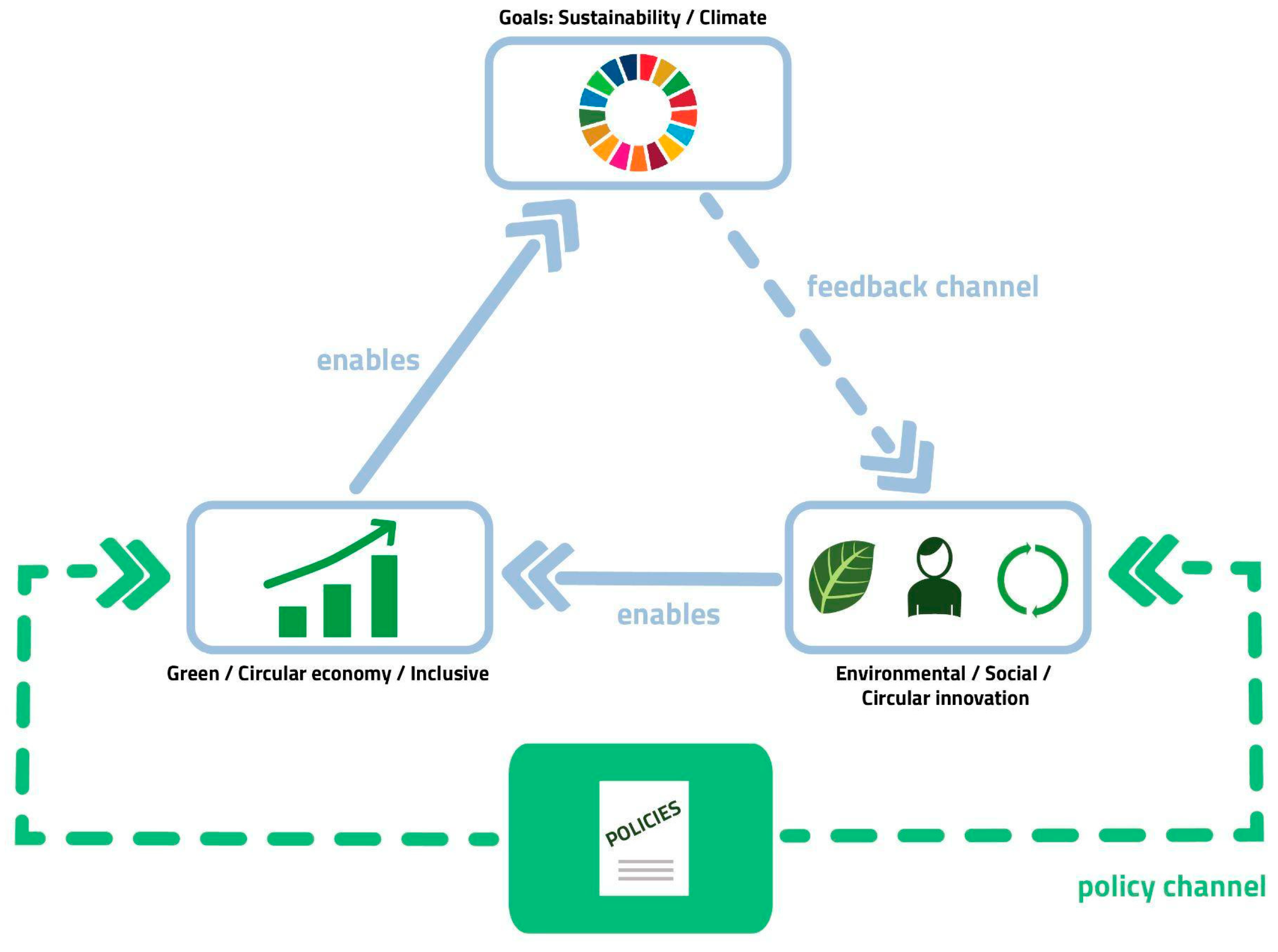

Discussion and Value Creation

6. Limitations and Further Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Codini, A. Le Cooperative Sociali; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zamagni, V.N. The Cooperative Enterprise: A Valid Alternative for a More Balanced Society. In Cooperatives in a Post-Growth Era Creating Cooperative Economics; Novkovic, S.S., Webb, T., Eds.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2014; pp. 194–210. [Google Scholar]

- Castellini, M.; Maran, L. An Overview of Management Systems in the Cooperative Sector. An Analysis of the Italian Leghe. J. Coop. Account. Report. 2012, 1, 5. Available online: https://saturn.smu.ca/webfiles/2012-1-2-p1.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Smith, M. Diversity and Identity in the Non-profit Sector: Lessons from LGBT Organizing in Toronto. Soc. Policy Adm. 2005, 39, 463–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Summary for Policymakers: Climate Change 2021. The Physical Science Basis. 2021. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_SPM_final.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Giannetti, B.F.; Diaz Lopez, F.J.; Liu, G.; Agostinho, F.; Sevegnani, F.; Almeida, C.M. A Resilient and Sustainable World: Contributions from Cleaner Production, Circular Economy, Eco-innovation, Responsible Consumption, and Cleaner Waste Systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 384, 135465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chioatto, E.; Zecca, E.; D’Amato, A. Which Innovations for a Circular Business Model? A Product Life-Cycle Approach. FEEM Working Paper 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, A.; Antunes, P.; Santos, R.; Mendonça, S. Eco-innovation in the transition to a circular economy: An analytical literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 2999–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, R.; Poirier, C.; Lacasse, M.; Murray, E. Circular Economy and Cooperatives—An Exploratory Survey. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer-Dixon, T. The Cooperative Enterprise: A Valid Alternative for a More Balanced Society. In Cooperatives in a Post-Growth Era Creating Cooperative Economics; Novkovic, S., Webb, T., Eds.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2014; pp. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Circular Economy Action Plan. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/strategy/circular-economy-action-plan_en (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Calle, F.; González-Moreno, N.; Carrasco, I.; Vargas-Vargas, M. Social Economy, Environmental Proactivity, Eco-Innovation and Performance in the Spanish Wine Sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUR-LEX—52011DC0899—EN—EUR-LEX. (n.d.). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=celex%3A52011DC0899 (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Könnölä, T.; Del Río González, P.; Carrillo-Hermosilla, J.; López, F.J.D. Innovación verde en América Latina y el Caribe: Marco conceptual|Publications. In Banco Interamericano De Desarrollo (IDB-TN-2 704); Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/publications/spanish/viewer/Innovacion-verde-en-America-Latina-y-el-Caribe-marco-conceptual.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Voinea, A. International Day of Cooperatives Theme Announced. Cooperative News, 3 May 2022. Available online: https://www.thenews.coop/162106/sector/regional-organisations/international-day-of-cooperatives-theme-announced/(accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Jossa, B. Cooperativismo, Capitalismo e Socialismo. Una Nuova Stella Polare per la Sinistra; Novalogos: Hague, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cropp, R.; Ingalsbe, G. Structure and scope of agricultural cooperatives. In Cooperatives in Agriculture; Cobia, D., Ed.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1989; pp. 35–67. [Google Scholar]

- van Bekkum, O.-F.; van Dijk, G. (Eds.) Agricultural Cooperatives in the European Union. Trends and Issues on the Eve of the 21st Century; Van Gorcum: Assen, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, A.; Wang, H.; Rahman, A.; Qian, L.; Memon, W.H. Evaluating the roles of the farmer’s cooperative for fostering environmentally friendly production technologies-a case of kiwi-fruit farmers in Meixian, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 301, 113858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arundel, A.; Kemp, R. Measuring eco-innovation. Res. Pap. Econ. 2009, 17, 1–40. Available online: http://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:324/wp2009-017.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Carrillo-Hermosilla, J.; del González, P.R.; Könnölä, T. What is eco-innovation? In Eco-Innovation; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harabi, N. Employment Effects of Ecological Innovations: An Empirical Analysis. Munich Personal RePEc Archive. 2000. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/4395/ (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Pansera, M. The Origins and Purpose of Eco-Innovation. Glob. Environ. 2011, 4, 128–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R. Eco-innovation: Definition, measurement and open research issues. Econ. Politica 2010, 3, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekins, P. Eco-innovation for environmental sustainability: Concepts, progress and policies. Int. Econ. Econ. Policy 2010, 7, 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reno, J. Waste and Waste Management. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2015, 44, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, K. Shaping System Innovation: Transformative environmental policies. In Sustainability and Innovation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraga, G.; Huysveld, S.; Mathieux, F.; Blengini, G.A.; Alaerts, L.; van Acker, K.; de Meester, S.; Dewulf, J. Circular economy indicators: What do they measure? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; Honkasalo, A.; Seppälä, J. Circular Economy: The Concept and its Limitations. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MahmoumGonbadi, A.; Genovese, A.; Sgalambro, A. Closed-loop supply chain design for the transition towards a circular economy: A systematic literature review of methods, applications and current gaps. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 323, 129101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt Morales, C.M.; Zartha Sossa, J.W. Circular economy in Latin America: A systematic literature review. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2479–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figge, F.; Thorpe, A.S.; Gutberlet, M. Definitions of the circular economy: Circularity matters. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 208, 107823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Liu, Y. Behind eco-innovation: Managerial environmental awareness and external resource acquisition. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 139, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.A. Encouraging innovative environmental actions: What companies and managers must do. J. World Bus. 2002, 37, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.A. Employee Environmental Innovation in Firms: Organizational and Managerial Factors; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ramus, C.A.; Steger, U. The roles of supervisory support behaviors and environmental policy in employee “Ecoinitiatives” at leading-edge European companies. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 605–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistov, V.; Carrillo-Hermosilla, J.; Aramburu, N. Open eco-innovation. Aligning cooperation and external knowledge with the levels of eco-innovation radicalness. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbairn, B. The Meaning of Rochdale: The Rochdale Pioneers and the Cooperative Principles. Research in Agricultural & Applied Economics. 1994. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/31778/ (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Bernardi, A.; Berranger, C.; Mannella, A.; Monni, S.; Realini, A. Sustainable but Not Spontaneous: Cooperatives and the Solidarity Funds in Italy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamagni, S.; Zamagni, V. Cooperative Enterprise: Facing the Challenge of Globalization; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, M.L. The Future of U.S. Agricultural Cooperatives: A Neo-Institutional Approach. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1995, 77, 1153–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J. Organisational principles for cooperative firms. Scand. J. Manag. 2001, 17, 329–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, T. PLATFORM COOPERATIVISM: Challenging the Corporate Sharing Economy; Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung: Berlin, Germany, 2016; Available online: https://eticasfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Scholz_Platform-Cooperativism.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Menzani, T.; Zamagni, V. Cooperative Networks in the Italian Economy. Enterp. Soc. 2010, 11, 98–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jossa, B. La Teoria Economica delle Cooperative di Produzione e la Possibile Fine del Capitalismo, 1st ed.; Giappichelli: Torino, Italy, 2005; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, R.A. Democracy and Its Critics; Yale University Press: New Heaven, CT, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bakaikoa, B.; Errasti, A.; Begiristain, A. Gobierno y democracia en los grupos empresariales cooperativos ante la globalización. CIRIEC-España 2004, 48, 53–77. [Google Scholar]

- Osti, G. Green social cooperatives in Italy: A practical way to cover the three pillars of sustainability? Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2012, 8, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neef, M.M. The Cooperative Enterprise: A Valid Alternative for a More Balanced Society. In Cooperatives in a Post-Growth Era Creating Cooperative Economics; Novkovic, S., Webb, T., Eds.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2014; pp. 15–39. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, N. The Cooperative Enterprise: A Valid Alternative for a More Balanced Society. In Cooperatives in a Post-Growth Era Creating Cooperative Economics; Novkovic, S., Webb, T., Eds.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2014; pp. 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Have, R.P.; Rubalcaba, L. Social innovation research: An emerging area of innovation studies? Res. Policy 2016, 45, 1923–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sci2 Team. Science of Science (Sci2) Tool. Indiana University and SciTech Strategies. 2019. Available online: https://sci2.cns.iu.edu (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Bergh, D.D.; Boyd, B.; Byron, K.; Gove, S.; Ketchen, D.J. What constitutes a methodological contribution? J. Manag. 2022, 48, 1835–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz López, F.J.; Montalvo, C. A comprehensive review of the evolving and cumulative nature of eco-innovation in the chemical industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 102, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera Delgado, D.; Díaz López, F.J.; Carrillo González, G. Energy transition, innovation, and direct uses of geothermal energy in Mexico: A thematic modeling analysis. Probl. Del Desarro. 2021, 52, 115–141. [Google Scholar]

- Lumivero. NVivo (Version 14). 2023. Available online: www.lumivero.com (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Cheng, P.; Zhang, G.; Sun, H. The Sustainable Supply Chain Network Competition Based on Non-Cooperative Equilibrium under Carbon Emission Permits. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnaro, C.; D’Urzo, M. Social Cooperation as a Driver for a Social and Solidarity Focused Approach to the Circular Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. Circular Economy in Europe; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016; Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/circular-economy-in-europe/download (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Elia, V.; Gnoni, M.G.; Tornese, F. Measuring circular economy strategies through index methods: A critical analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2741–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, R.H.; Hunka, A.D.; Linder, M.; Whalen, K.A.; Habibi, S. Product Labels for the Circular Economy: Are Customers Willing to Pay for Circular? Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buch, R.; Marseille, A.; Williams, M.; Aggarwal, R.; Sharma, A. From Waste Pickers to Producers: An Inclusive Circular Economy Solution through Development of Cooperatives in Waste Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda IT, P.; Fidelis, R.; de Souza Fidelis, D.A.; Pilatti, L.A.; Picinin, C.T. The Integration of Recycling Cooperatives in the Formal Management of Municipal Solid Waste as a Strategy for the Circular Economy—The Case of Londrina, Brazil. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łȩkawska-Andrinopoulou, L.; Tsimiklis, G.; Leick, S.; Moreno Nicolás, M.; Amditis, A. Circular Economy Matchmaking Framework for Future Marketplace Deployment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, K.; Korevaar, G.; Nikolic, I.; Herder, P. Actor Behaviour and Robustness of Industrial Symbiosis Networks: An Agent-Based Modelling Approach. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2021, 24, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, L.; Carenzo, S.; Juarez, P. When Circular Economy Meets Inclusive Development. Insights from Urban Recycling and Rural Water Access in Argentina. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S. Waste Management in Australia Is an Environmental Crisis: What Needs to Change so Adaptive Governance Can Help? Sustainability 2020, 12, 9212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazan, D.M.; Yazdanpanah, V.; Fraccascia, L. Learning strategic cooperative behavior in industrial symbiosis: A game-theoretic approach integrated with agent-based simulation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2078–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellitto, M.A.; Almeida FA, D. Strategies for value recovery from industrial waste: Case studies of six industries from Brazil. Benchmarking Int. J. 2019, 27, 867–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herczeg, G.; Akkerman, R.; Hauschild, M.Z. Supply chain collaboration in industrial symbiosis networks. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulrow, J.S.; Derrible, S.; Ashton, W.S.; Chopra, S.S. Industrial Symbiosis at the Facility Scale. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarassy, C.; Horvath, B.; Kovacs, A.; Szoke, L.; Takacs-Gyorgy, K. A Circular Evaluation Tool for Sustainable Event Management—An Olympic Case Study. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2018, 14, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ada, E.; Sagnak, M.; Uzel, R.A.; Balcıoğlu, R. Analysis of barriers to circularity for agricultural cooperatives in the digitalization era. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2021, 71, 932–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado-Caruso, N.; Segarra-Oña, M.; Peiró-Signes, N.; Portnoy, I.; Navarro, E. Drivers of Eco-innovation in Industrial Clusters—A Case Study in the Colombian Metalworking Sector. In Computer Information Systems and Industrial Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabadán, A.; Triguero, N.; Gonzalez-Moreno, N. Cooperation as the Secret Ingredient in the Recipe to Foster Internal Technological Eco-Innovation in the Agri-Food Industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabadán, A.; González-Moreno, N.; Sáez-Martínez, F.J. Improving Firms’ Performance and Sustainability: The Case of Eco-Innovation in the Agri-Food Industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennings, K. Redefining innovation—Eco-innovation research and the contribution from ecological economics. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 32, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Es, J.C.; Pampel, F.C. Environmental practices: New strategies needed. J. Ext. 1976, 19, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hamburg, I.; Vlăduţ, G.; O’Brien, E. Fostering eco-innovation in SMEs through bridging research, education and industry for building a business oriented model. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Excellence, Bucharest, Romania, 30–31 March 2017; Volume 11, pp. 1050–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreschi, A.; Piras, L.; Heck, F. Barriers to Efficient Knowledge Transfer for a Holistic Circular Economy: Insights towards Green Job Developments and Training for Young Professionals. Youth 2023, 3, 553–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, J.A.; Tan, H. Circular economy: Lessons from China. Nature 2016, 531, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carini, C.; Borzaga, C.; Carpita, M. Case Studies on Brazil, Canada, Colombia, the Philippines, the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Paris Agreement: Climate Action. 2015. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/international-action-climate-change/climate-negotiations/paris-agreement_en#:~:text=The%20Paris%20Agreement%20sets%20out,support%20them%20in%20their%20efforts (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- United Nations. International Day of Cooperatives 2020: COOPS 4 Climate Action|Division for Inclusive Social Development (DISD). United Nations: Department of Economic and Social Affairs Social Inclusion. 4 July 2020. Available online: https://social.desa.un.org/issues/cooperatives/events/international-day-of-cooperatives-2020-coops-4-climate-action (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Jelinski, L.W.; Graedel, T.E.; Laudise, R.A.; McCall, D.W.; Patel, C.K. Industrial ecology: Concepts and approaches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 793–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R.; Arundel, A.; Rammer, C.; Miedzinski, M.; Tapia, C.; Barbieri, N.; Türkeli, S.; Bassi, A.; Mazzanti, M.; Chapman, D.; et al. Measuring eco-innovation for a green economy. Sustainability 2019, 66, 391–404. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, J.C.-H. Towards a care perspective on waste: A new direction in discard studies. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2022, 23996544211063383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gille, Z. From the Cult of Waste to the Trash Heap of History: The Politics of Waste in Socialist and Postsocialist Hungary; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan, S.; Erbis, S.; Isaacs, J.A.; Kamarthi, S. Correction: Novel keyword co-occurrence network-based methods to foster systematic reviews of scientific literature. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarivate. KeyWords Plus Generation, Creation, and Changes. 9 June 2022. Available online: https://support.clarivate.com/s/article/KeyWords-Plus-generation-creation-and-changes?language=en_US (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Kirchherr, J.; Urbinati, A.; Hartley, K. Circular economy: A new research field? J. Ind. Ecol. 2023, 27, 1239–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaget, P.; Carvalho, F. Investigating the Regulatory-Push of Eco-innovations in Brazilian Companies. Sustain. Des. Manuf. 2016, 2016, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giagnocavo, C. Caring for the Environment and ICA principles. In Proceedings of the ICA CCR European Research Conference 2022 “Rethinking Cooperatives: From Local to Global and from the Past to the Future”, Athens, Greece, 14 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulos, M. Bridging co-operation’s communication gap: The Statement on the Cooperative Identity, the sociology of cooperative education’s shifting terrain, and the problem of public opinion. J. Coop. Organ. Manag. 2022, 10, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novkovic, S.N. Circular Economy in Cooperatives. In Proceedings of the Global Innovation Coop Summit 2023 Edition, Montreal, QC, Canada, 27–29 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Value Set on the Environment | Aim of the Social Enterprise | |

|---|---|---|

| Produce | Produce and Inhabit | |

| Instrumental | A—Simple environmental services (e.g., urban cleansing) SIMPLE GSE | B—Territorial promotion services (e.g., environmental education) TERRITORIAL GSE |

| Final | C—Services with high technical-innovative content (e.g., solar energy plants) INNOVATIVE GSE | D—Services incorporating lifestyles (e.g., residences with self-contained consumption) COMMUNITARIAN GSE |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guerreschi, A.; Díaz López, F.J. A Bibliometric Analysis on Cooperatives in Circular Economy and Eco-Innovation Studies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115595

Guerreschi A, Díaz López FJ. A Bibliometric Analysis on Cooperatives in Circular Economy and Eco-Innovation Studies. Sustainability. 2023; 15(21):15595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115595

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuerreschi, Asia, and Fernando J. Díaz López. 2023. "A Bibliometric Analysis on Cooperatives in Circular Economy and Eco-Innovation Studies" Sustainability 15, no. 21: 15595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115595

APA StyleGuerreschi, A., & Díaz López, F. J. (2023). A Bibliometric Analysis on Cooperatives in Circular Economy and Eco-Innovation Studies. Sustainability, 15(21), 15595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115595