Impact of Work and Non-Work Support on Employee Well-Being: The Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory

2.2. Family Member Support and Employee Well-Being

2.3. Psychological Capital as a Mediator

2.4. Perceived Organizational Support as a Moderator

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analytic Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Construct and Discriminant Validity Analyses

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Implications for Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Le, H.; Jiang, Z.; Radford, K. Leader-member exchange and subjective well-being: The moderating role of metacognitive cultural intelligence. Pers. Rev. 2021, 50, 954–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.M.; Rothstein, H.R. Effects of occupational stress management intervention programs: A meta-analysis. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2008, 13, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, A.L.; Cummins, R.A.; Mcpherson, W. An investigation into the cross-cultural equivalence of the Personal Wellbeing Index. Soc. Indic. Res. 2005, 72, 403–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, P.; Taras, V.; Uggerslev, K.; Bosco, F. The happy culture: A theoretical, meta-analytic, and empirical review of the relationship between culture and wealth and subjective well-being. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 22, 128–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Nielsen, I.; Smyth, R.; Hirst, G. Mediating role of psychological capital in the relationship between social support and wellbeing of refugees. Int. Migr. 2018, 56, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuzovic, S.; Kabadayi, S. The influence of social distancing on employee well-being: A conceptual framework and research agenda. J. Serv. Manag. 2021, 32, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A. Confucianism and development in East Asia. J. Contemp. Asia 1996, 26, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.; Lee, J.; Nielsen, I.; Nguyen, T.L.A. Turnover intentions: The roles of job satisfaction and family support. Pers. Rev. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The Ecology of Stress; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B.; Norman, S.M. Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Lee, A. Work and nonwork outcomes of workplace incivility: Does family support help? J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.M.; Trougakos, J.P.; Cheng, B.H. Are anxious workers less productive workers? It depends on the quality of social exchange. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.P.; Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmer, N.K.; Elfering, A.; Jacobshagen, N.; Perrot, T.; Beehr, T.A.; Boos, N. The emotional meaning of instrumental social support. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2008, 15, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abendroth, A.K.; Den Dulk, L. Support for the work-life balance in Europe: The impact of state, workplace, and family support on work-life balance satisfaction. Work. Employ. Soc. 2011, 25, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, A.H.; Casper, W.J.; Payne, S.C. How does spouse career support relate to employee turnover? Work interfering with family and job satisfaction as mediators. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, R.A.; Gullone, E.; Lau, A.L.D. A Model of Subjective Well-Being Homeostasis: The Role of Personality. In The Universality of Subjective Wellbeing Indicators: Social Indicators Research Series, 16; Gullone, E., Cummins, R.A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Bakker, A.B.; Jokisaari, M. A 35-year follow-up study on burnout among Finnish employees. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, S.Y.; Cheng, L.; Wong, D.F. Family emotional support, positive psychological capital and job satisfaction among Chinese white-collar workers. J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 16, 561–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Cioffi, D.; Taylor, C.B.; Brouillard, M.E. Perceived self-efficacy in coping with cognitive stressors and opioid activation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 55, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.; He, J.; Morrison, A.M.; Andres Coca-Stefaniak, J. Effects of tourism CSR on employee psychological capital in the COVID-19 crisis from the perspective of conservation of resources theory. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2716–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, M.C. How the contextual constraints and tensions of a transitional context influence individuals’ negotiations of meaningful work–the case of Vietnam. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 33, 835–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffeld, S.; Spurk, D. Why does psychological capital foster subjective and objective career success? The mediating role of career-specific resources. J. Career Assess. 2022, 30, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafoor, A.; Haar, J. Does job stress enhance employee creativity? Exploring the role of psychological capital. Pers. Rev. 2021, 51, 644–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Neveu, J.P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Ucbasaran, D.; Zhu, F.; Hirst, G. Psychological capital: A review and synthesis. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, S120–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, I.; Newman, A.; Smyth, R.; Hirst, G.; Heilemann, B. The influence of instructor support, family support and psychological capital on the well-being of postgraduate students: A moderated mediation model. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 2099–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived Organizational Support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Nawaz, M.M. Antecedents and outcomes of perceived organizational support: A literature survey approach. J. Manag. Dev. 2015, 34, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; van Rijn, M.B.; Sanders, K. Perceived organizational support and knowledge sharing: Employees’ self-construal matters. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 2217–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Norman, S.M.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B. The mediating role of psychological capital in the supportive organizational climate-employee performance relationship. J. Organ. Behav. 2008, 29, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Luk, V.; Leung, A.; Lo, S. Role stressors, interrole conflict, and well-being: The moderating influence of spousal support and coping behaviors among employed parents in Hong Kong. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 54, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, C.M.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common methods variance detection in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.F. Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.; McKay, J. Chinese and Vietnamese international students in Australia. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2018, 32, 1278–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolzen, N. The concept of psychological capital: A comprehensive Review. Manag. Rev. Q. 2018, 68, 237–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M.; Gruman, J.A. Organizational socialization and positive organizational behaviour: Implications for theory, research, and practice. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2011, 28, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigah, N.; Davis, A.J.; Hurrell, S.A. The impact of buddying on psychological capital and work engagement: An empirical study of socialization in the professional services sector. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2012, 54, 891–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, D.L.; Rosopa, P.J. The advantages and limitations of using meta-analysis in human resource management research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2017, 27, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.B.E.; De Jong, M.G.; Baumgartner, H. Socially desirable response tendencies in survey research. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.; Fernando, M.; Caputi, P. The Relationship Between Responsible Leadership and Organisational Commitment and the Mediating Effect of Employee Turnover Intentions: An Empirical Study with Australian Employees. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 759–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | χ2 (df) | TLI | CFI | GFI | RMSEA | 90% CI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Factor Model | 2008.81 (350) | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.14 | 0.13–0.19 | 0.13 |

| 2-Factor Model | 1549.05 (349) | 0.61 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.12 | 0.11–0.13 | 0.11 |

| 3-Factor Model | 1406.96 (347) | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.11 | 0.11–0.12 | 0.11 |

| 4-Factor Model | 765.63 (335) | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.07 | 0.07–0.08 | 0.07 |

| Variables | Mean | SD | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Gender | 0.73 | 0.44 | -- | |||||

| (2) Age | 41.61 | 9.98 | 0.03 | -- | ||||

| (3) Family member support | 4.21 | 0.53 | 0.04 | 0.05 | -- | |||

| (4) Perceived organizational support | 3.55 | 0.56 | 0.02 | 0.18 ** | 0.24 ** | -- | ||

| (5) Psychological capital | 3.87 | 0.42 | 0.04 | 0.24 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.43 ** | -- | |

| (6) Well-being | 7.06 | 1.34 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.32 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.33 ** | -- |

| Variables | Model 1 Well-Being | Model 2 PsyCap | Model 3 Well-Being | Model 4 PsyCap | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Gender | −0.16 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.18 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 ** | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 ** | 0.00 |

| FMS | 0.77 ** | 0.16 | 0.29 ** | 0.05 | 0.54 * | 0.17 | 0.24 ** | 0.05 |

| PsyCap | 0.78 ** | 0.22 | ||||||

| POS | 0.27 ** | 0.04 | ||||||

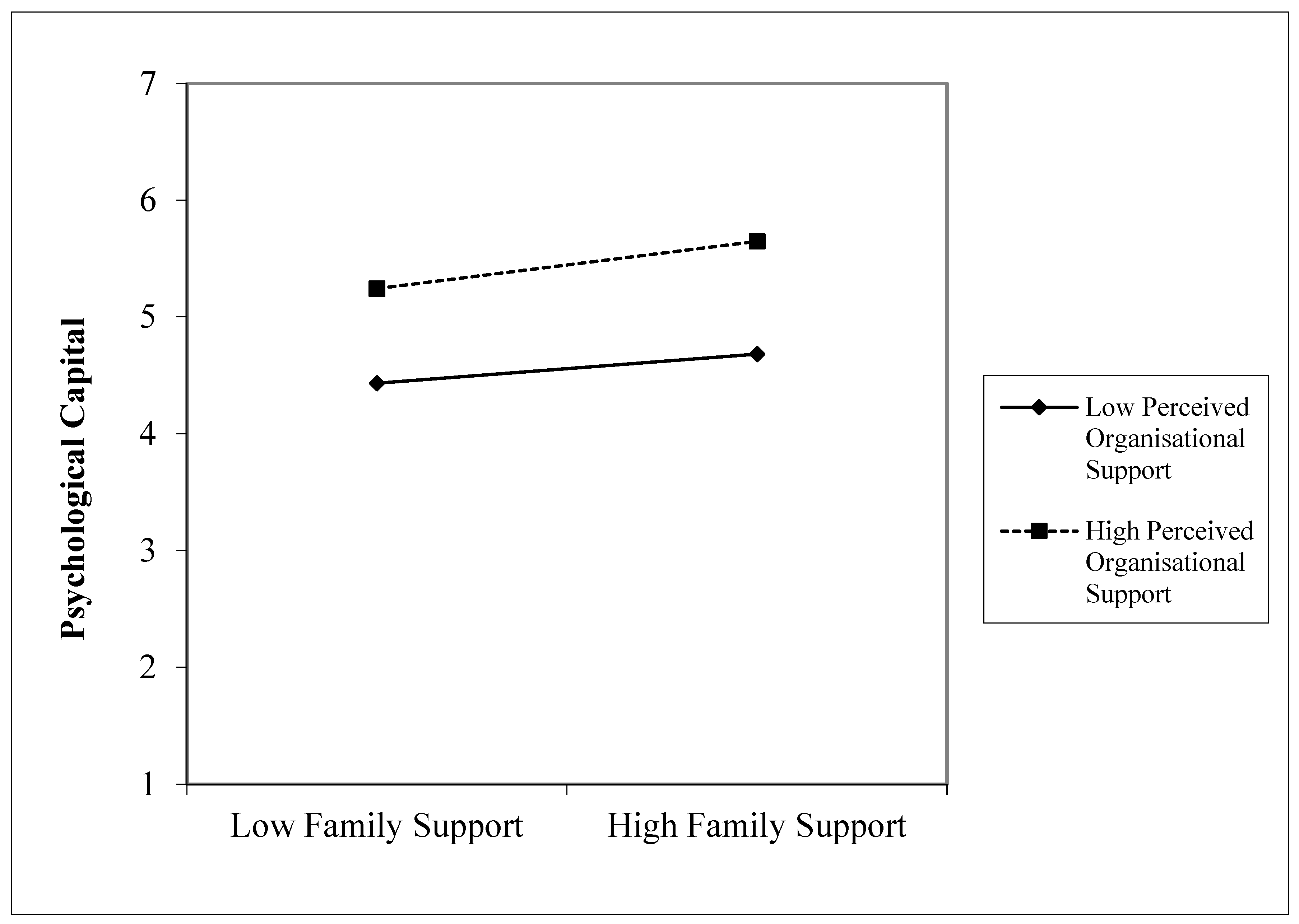

| POS × FMS | 0.15 * | 0.07 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.31 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.31 ** | ||||

| (Δ) R² | 0.01 * | |||||||

| Value of Moderator (POS) | Indirect Effect | SE | 95% CI Lower Limit | 95% CI Upper Limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 SD | 0.15 | 0.06 * | 0.04 | 0.26 |

| Mean | 0.24 | 0.04 * | 0.15 | 0.33 |

| +1 SD | 0.32 | 0.07 * | 0.19 | 0.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Le, H.; Gopalan, N.; Lee, J.; Kirige, I.; Haque, A.; Yadav, V.; Lambropoulos, V. Impact of Work and Non-Work Support on Employee Well-Being: The Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15808. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215808

Le H, Gopalan N, Lee J, Kirige I, Haque A, Yadav V, Lambropoulos V. Impact of Work and Non-Work Support on Employee Well-Being: The Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support. Sustainability. 2023; 15(22):15808. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215808

Chicago/Turabian StyleLe, Huong, Neena Gopalan, Joohan Lee, Isuru Kirige, Amlan Haque, Vanita Yadav, and Victoria Lambropoulos. 2023. "Impact of Work and Non-Work Support on Employee Well-Being: The Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support" Sustainability 15, no. 22: 15808. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215808

APA StyleLe, H., Gopalan, N., Lee, J., Kirige, I., Haque, A., Yadav, V., & Lambropoulos, V. (2023). Impact of Work and Non-Work Support on Employee Well-Being: The Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support. Sustainability, 15(22), 15808. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215808