A Systematic Review of International and Internal Climate-Induced Migration in Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Climate-Induced Migration: An Overview

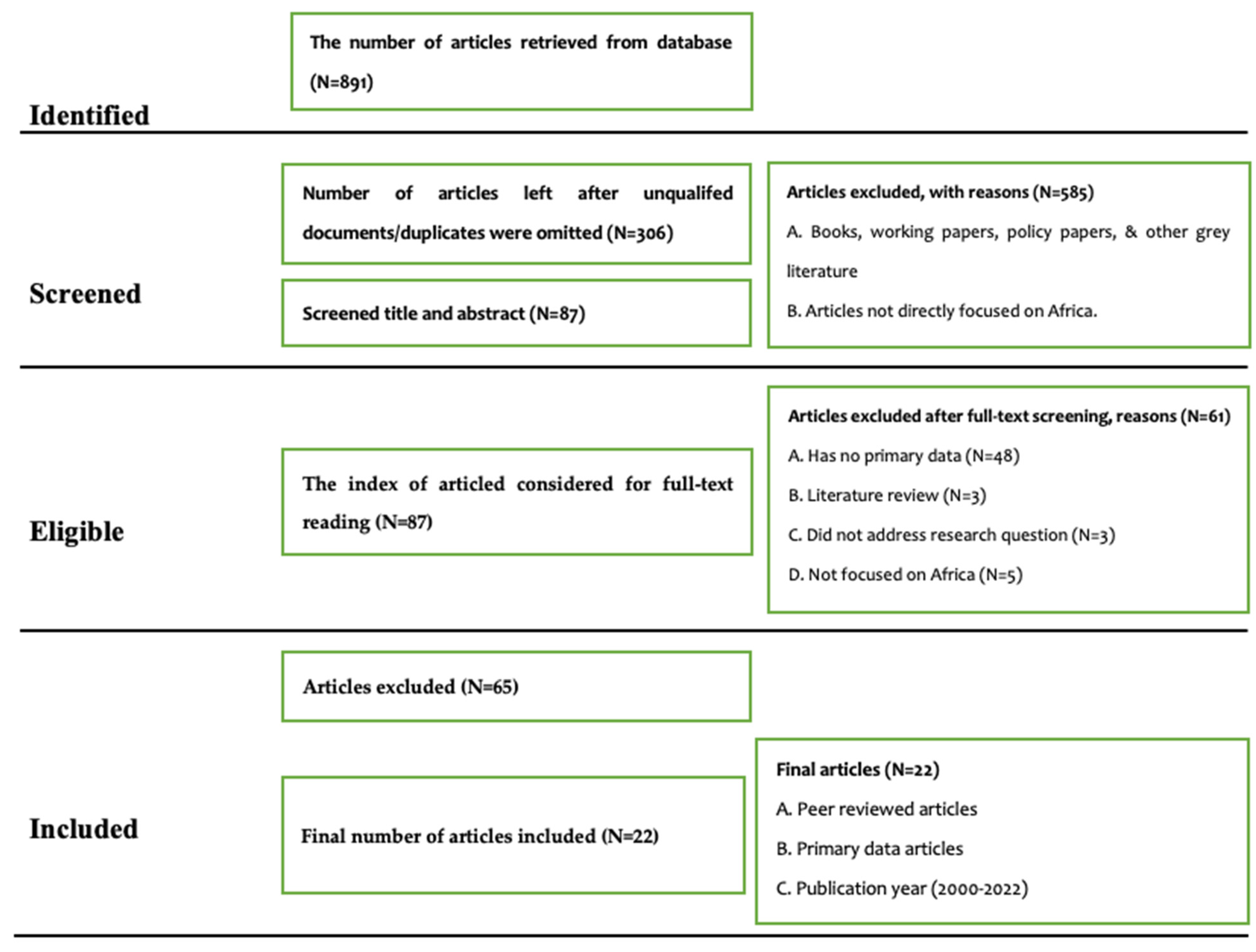

3. Method

4. Data Synthesis

5. Results

5.1. Study Context

5.2. Emerging Issues in the Reviewed Studies

5.3. Environmental Factors Influencing Migration

5.4. Migration as an Adaptation Strategy

5.5. Environmental and Non-Environmental Forces Influencing Migration

5.6. Climate Change and Immobility

5.7. Climate Change and Internal Migration

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chirisa, I.; Bandauko, E. Civil society advocacy and environmental migration in Zimbabwe: A case study in public policy. In Organizational Perspectives on Environmental Migration; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cottier, F.; Flahaux, M.-L.; Ribot, J.; Seager, R.; Ssekajja, G. Framing the frame: Cause and effect in climate-related migration. World Dev. 2022, 158, 106016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R.; Dimitrova, A.; Muttarak, R.; Crespo Cuaresma, J.; Peisker, J. A meta-analysis of country-level studies on environmental change and migration. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 10, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigaud, K.K.; de Sherbinin, A.; Jones, B.; Bergmann, J.; Clement, V.; Ober, K.; Schewe, J.; Adamo, S.; McCusker, B.; Heuser, S.; et al. Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azumah, S.B.; Ahmed, A. Climate-induced migration among maize farmers in Ghana: A reality or an illusion? Environ. Dev. 2023, 45, 100808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baada, J.N.; Baruah, B.; Luginaah, I. Looming crisis—Changing climatic conditions in Ghana’s breadbasket: The experiences of agrarian migrants. Dev. Pract. 2020, 31, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.P.L.; Sean, C. Do climate uncertainties trigger farmers’ out-migration in the Lower Mekong Region? Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 3, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, K.; Garbe, L. Droughts, livelihoods, and human migration in northern Ethiopia. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2019, 19, 1101–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrotzki, R.J.; DeWaard, J. Putting trapped populations into place: Climate change and inter-district migration flows in Zambia. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2018, 18, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simatele, D.; Simatele, M. Migration as an adaptive strategy to climate variability: A study of the Tonga-speaking people of Southern Zambia. Disasters 2015, 39, 762–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinke, K.; Bergmann, J.; Blocher, J.; Upadhyay, H.; Hoffmann, R. Migration as Adaptation? Migr. Stud. 2020, 8, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinke, K.; Rottmann, S.; Gornott, C.; Zabre, P.; Nayna Schwerdtle, P.; Sauerborn, R. Is migration an effective adaptation to climate-related agricultural distress in sub-Saharan Africa? Popul. Environ. 2022, 43, 319–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczan, D.J.; Orgill-Meyer, J. The impact of climate change on migration: A synthesis of recent empirical insights. Clim. Chang. 2020, 158, 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, H.; Ahadzie, D.K. Causes, impacts and coping strategies of floods in Ghana: A systematic review. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, B.; Mensah, H. Rethinking climate migration in sub-Saharan Africa from the perspective of tripartite drivers of climate change. SN Soc. Sci. 2022, 2, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borderon, M.; Sakdapolrak, P.; Muttarak, R.; Kebede, E.; Pagogna, R.; Sporer, E. Migration influenced by environmental change in Africa. Demogr. Res. 2018, 41, 491–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.C.; Orchiston, C. A systematic review of climate migration research: Gaps in existing literature. SN Soc. Sci. 2022, 2, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, C.; Sierra-Huedo, M.L.; Chinarro, D. Climate Change-Induced Migration in Morocco: Sub-Saharian and Moroccan Migrants. In Mediterranean Mobilities: Europe’s Changing Relationships; Paradiso, M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kniveton, D.R.; Smith, C.D.; Black, R. Emerging migration flows in a changing climate in dryland Africa. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012, 2, 444–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassin, L.; Melindi-Ghidi, P.; Prieur, F. Confronting climate change: Adaptation vs. migration in Small Island Developing States. Resour. Energy Econ. 2022, 69, 101301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilleør, H.B.; Van den Broeck, K. Economic drivers of migration and climate change in LDCs. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, S70–S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaawen, S.; Rademacher-Schulz, C.; Schraven, B.; Segadlo, N. Chapter 2-Drought, Migration, and Conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa: What Are the Links and Policy Options? In Current Directions in Water Scarcity Research; Mapedza, E., Tsegai, D., Bruntrup, M., Mcleman, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Olaniyan, O.F.; Nagle Alverio, G. Where to go? Migration and climate change response in West Africa. Geoforum 2022, 137, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guodaar, L.; Asante, F.; Eshun, G.; Abass, K.; Afriyie, K.; Appiah, D.O.; Gyasi, R.; Atampugre, G.; Addai, P.; Kpenekuu, F. How do climate change adaptation strategies result in unintended maladaptive outcomes? Perspectives of tomato farmers. J. Veg. Sci. 2020, 26, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjaminsen, T.A.; Maganga, F.P.; Abdallah, J.M. The Kilosa Killings: Political Ecology of a Farmer–Herder Conflict in Tanzania. Dev. Chang. 2009, 40, 423–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabot, C. Climate Change and Farmer–Herder Conflicts in West Africa. In Climate Change, Security Risks and Conflict Reduction in Africa: A Case Study of Farmer-Herder Conflicts over Natural Resources in Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and Burkina Faso 1960–2000; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 11–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengist, W.; Soromessa, T.; Legese, G. Method for conducting systematic literature review and meta-analysis for environmental science research. MethodsX 2020, 7, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnall, A. A climate of control: Flooding, displacement and planned resettlement in the Lower Zambezi River valley, Mozambique. Geogr. J. 2014, 180, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu, M.; Codjoe, S.N.A.; Sward, J. Climate change and internal migration intentions in the forest-savannah transition zone of Ghana. Popul. Environ. 2014, 35, 341–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagabhatla, N.; Cassidy-Neumiller, M.; Francine, N.N.; Maatta, N. Water, conflicts and migration and the role of regional diplomacy: Lake Chad, Congo Basin, and the Mbororo pastoralist. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 122, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfo, S.; Fonta, W.M.; Diasso, U.J.; Nikiéma, M.P.; Lamers, J.P.A.; Tondoh, J.E. Climate- and Environment-Induced Intervillage Migration in Southwestern Burkina Faso, West Africa. Weather Clim. Soc. 2017, 9, 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietaer, S.; Durand-Delacre, D. Situating “migration as adaptation” discourse and appraising its relevance to Senegal’s development sector. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 126, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, J.; Ide, T.; Sakdapolrak, P.; Kassa, E.; Hermans, K. Deciphering interwoven drivers of environment-related migration—A multisite case study from the Ethiopian highlands. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2020, 63, 102094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmannskog, V. Climate Change, Human Mobility, and Protection: Initial Evidence from Africa. Refug. Surv. Q. 2010, 29, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, J.; Hermans, K.; Wiederkehr, C.; Kassa, E.; Thober, J. Investigating environment-related migration processes in Ethiopia—A participatory Bayesian network. Ecosyst. People 2021, 17, 128–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronis, L.; McLeman, R. Environmental influences on African migration to Canada: Focus group findings from Ottawa-Gatineau. Popul. Environ. 2014, 36, 234–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tafere, M. Forced displacements and the environment: Its place in national and international climate agenda. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 224, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suckall, N.; Fraser, E.; Forster, P.; Mkwambisi, D. Using a migration systems approach to understand the link between climate change and urbanisation in Malawi. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 63, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchiori, L.; Maystadt, J.-F.; Schumacher, I. The impact of weather anomalies on migration in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2012, 63, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codjoe, S.N.A.; Nyamedor, F.H.; Sward, J.; Dovie, D.B. Environmental hazard and migration intentions in a coastal area in Ghana: A case of sea flooding. Popul. Environ. 2017, 39, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suckall, N.; Fraser, E.; Forster, P. Reduced migration under climate change: Evidence from Malawi using an aspirations and capabilities framework. Clim. Dev. 2017, 9, 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Call, M.; Gray, C. Climate anomalies, land degradation, and rural out-migration in Uganda. Popul. Environ. 2020, 41, 507–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinbami, C.A.O. Migration and climate change impacts on rural entrepreneurs in nigeria: A gender perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayar, M.; Aral, M.M. An Analysis of Large-Scale Forced Migration in Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng’ang’a, S.K.; Bulte, E.H.; Giller, K.E.; McIntire, J.M.; Rufino, M.C. Migration and Self-Protection Against Climate Change: A Case Study of Samburu County, Kenya. World Dev. 2016, 84, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Praag, L. Can I move or can I stay? Applying a life course perspective on immobility when facing gradual environmental changes in Morocco. Clim. Risk Manag. 2021, 31, 100274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrorillo, M.; Licker, R.; Bohra-Mishra, P.; Fagiolo, G.; DEstes, L.; Oppenheimer, M. The influence of climate variability on internal migration flows in South Africa. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 39, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessoe, K.; Manning, D.T.; Taylor, J.E. Climate change and labour allocation in rural Mexico: Evidence from annual fluctuations in weather. Econ. J. 2018, 128, 230–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrotzki, R.J.; Riosmena, F.; Hunter, L.M. Do rainfall deficits predict US-bound migration from rural Mexico? Evidence from the Mexican census. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2013, 32, 129–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohra-Mishra, P.; Oppenheimer, M.; Cai, R.; Feng, S.; Licker, R. Climate variability and migration in the Philippines. Popul. Environ. 2016, 38, 286–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, K. Natural hazards, internal migration and protests in Bangladesh. J. Peace Res. 2021, 58, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanov, R.; Kelman, I.; Ullah, A.A.; Duží, B.; Procházka, D.; Blahůtová, K.K. Local expert perceptions of migration as a climate change adaptation in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioli, G.; Khan, T.; Bisht, S.; Scheffran, J. Migration as an adaptation strategy and its gendered implications: A case study from the Upper Indus Basin. Mt. Res. Dev. 2014, 34, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, C.K.; Gupta, V.; Chattopadhyay, U.; Amarayil Sreeraman, B. Migration as adaptation strategy to cope with climate change: A study of farmers’ migration in rural India. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2018, 10, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, K.E.; Bronen, R.; Fernando, N.; Klepp, S. The complex decision-making of climate-induced relocation: Adaptation and loss and damage. Clim. Policy 2018, 18, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, M.M.G.; Cotton, M.; Friend, R. Climate change and non-migration—Exploring the role of place relations in rural and coastal Bangladesh. Popul. Environ. 2022, 44, 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, G.; Lyu, Q.; Shangguan, Z.; Jiang, T. Facing climate change: What drives internal migration decisions in the karst rocky regions of Southwest China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutor, S.K.; Akyea, T.A.; Arku, G. Climate change-(im)mobility nexus: Perspectives of voluntary immobile populations from three coastal communities in Ghana. J. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2023. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, C.; Sukamdi, S.; Rijanta, R. Exploring Migration Hold Factors in Climate Change Hazard-Prone Area Using Grounded Theory Study: Evidence from Coastal Semarang, Indonesia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farbotko, C. Voluntary immobility: Indigenous voices in the Pacific. Forced Migr. Rev. 2018, 57, 81–83. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Author(s) and Title | Study Context | Thematic Area(s) | Methodological Approach | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Arnall, A. (2014) [29]. A climate of control: flooding, displacement and planned resettlement in the Lower Zambezi River valley, Mozambique | Mozambique | Climate change adaptation measure | A total of 19 semi-structured interviews with key informants, including academics, donors, and NGOs. A total of 65 semi-structured individual and focus group discussions with farmers and leaders of community-based organizations. The author also used secondary data. | 1. Most participants believed that floods in the lower Zambezi Valley are a threat to lives and livelihoods. 2. Resettlement initiatives are affected by several factors. 3. Government interventions for climate resilience do not directly benefit local populations. |

| 2. | Abu, M., Codjoe, S. N. A., and Sward, J. (2014) [30]. Climate change and internal migration intentions in the forest-savannah transition zone of Ghana. | Ghana | Climate change and internal migration | Household survey of 200 households in two communities. Data was analyzed using quantitative techniques. | 1. Areas with perceived environmental stressors were not a primary predictor of migratory intentions. 2. The decision to migrate depends on a multidimensional factor 3. Household heads are more likely to nurture migration intentions. |

| 3. | Nagabhatla, N., Cassidy-Neumiller, M., Francine, N. N., and Maatta, N. (2021) [31]. Water, conflicts and migration and the role of regional diplomacy: Lake Chad, Congo Basin, and the Mbororo pastoralist. | Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) | Environmental and non-environmental influence on migration | The survey was conducted in the DRC. Questionnaires and focus group discussions with stakeholder was conducted. The study also uses geostatistical methods and remote sensing to verify changes over time. | 1. The intersection of socio-economic and political stressors contribute to forced migration. 2. Surface water level reduction in the Lake Chad Basin has contributed to unproductive agriculture yield resulting in displacement, change in profession, and migration. |

| 4. | Sanfo, S., Fonta, W. M., Diasso, U. J., Nikiéma, M. P., Lamers, J. P. A., and Tondoh, J. E. (2017) [32]. Climate- and Environment-Induced Intervillage Migration in Southwestern Burkina Faso, West Africa. | Burkina Faso | Environmental factors influencing migration | Data was collected in the southwestern region of Burkina Faso. The study was conducted in 12 villages with functioning meteorological stations. The authors used both in-depth interviews and focus group discussions covering a total of 158 households. | 1. farmers’ perceptions of climate change are directly linked to climatic impacts on their livelihoods. 2. Farmers did not link climatic changes directly to migration. 3. Farmers identified forest and soil conditions as primary drivers of migration. 4. Also, farmers identified non-environmental factors of migration. |

| 5. | Lietaer, S., and Durand-Delacre, D. (2021) [33]. Situating “migration as adaptation” discourse and appraising its relevance to Senegal’s development sector. | Senegal | Migration as an adaptation strategy | A total of 90 qualitative interviews were conducted with Senegalese policymakers, politicians, and civil servants. | 1. Participants acknowledge that climate conditions did not solely influence migration. 2. The authors also found that the activities of international donors shape the direction and narrative of irregular migration and displacement in Africa. |

| 6. | Groth, J., Ide, T., Sakdapolrak, P., Kassa, E., and Hermans, K. (2020) [34]. Deciphering interwoven drivers of environment-related migration—A multisite case study from the Ethiopian highlands | Ethiopia | Environmental factors influencing migration | A total of 18 focus group sessions were conducted in four districts; 42 semi-structured interviews were conducted with key informants and 20 interviews with returnees. | 1. Land degradation and precipitation in northern Ethiopia negatively affect agriculture which can lead to migration. 2. Young participants expressed a stronger desire to live and work elsewhere due to harsh environmental conditions on agricultural activities. 3. Individual factors are not strong predictors of migration. |

| 7. | Kolmannskog, V. (2010) [35]. Climate Change, Human Mobility, and Protection: Initial Evidence from Africa. | Somalia and Burundi | Environmental and non-environmental influence on migration | A total of 49 semi-structured interviews were conducted with experts and affected people. | 1. Climate stressors such as drought are recurrent in Somalia, affecting people’s livelihoods. 2. Most Somali pastoralists always move to greener forest belts during periods of droughts. 3. Poor pastoral households with no means of mobility are forced to stay in areas with less rainfall. 4. Lack of government measures to regulate warring activities and misuse/overuse of natural resources has affected the environment. |

| 8. | Groth, J., Hermans, K., Wiederkehr, C., Kassa, E., and Thober, J. (2021) [36]. Investigating environment-related migration processes in Ethiopia—A participatory Bayesian network. | Ethiopia | Environmental factors influencing migration | A total of 42 semi-structured household interviews, 18 focus group discussions, five expert interviews, and 20 migrant interviews in six districts. | 1. Agricultural activities directly influence migration since it is a livelihood activity. 2. Contrary, insufficient agricultural yield can impact a household’s economic capital, potentially causing migration. 3. In instances where agricultural and non-agricultural activities reap positive returns migration reduces. |

| 9. | Veronis, L., and McLeman, R. (2014) [37]. Environmental influences on African migration to Canada: focus group findings from Ottawa-Gatineau. | Djibouti, Somalia, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Congo-Brazzaville, Cote d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Guinea, Rwanda, and Togo | Environmental factors influencing migration | Seven focus groups consisting of 47 migrants (24 men and 23 women) from the Horn of Africa were conducted for the study. | 1. Participants believe that environmental factors trigger internal migration; however, none cited environmental stressors as immediate factors for their migration to Canada. 2. Most participants agreed environmental pressures contributed to the socio-economic factors that influenced their migration to Canada. |

| 10. | Tafere, M. (2018) [38]. Forced displacements and the environment: Its place in national and international climate agenda. | Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Sudan, and Uganda | Environmental factors causing displacement | The study combined the following methods: (i) meta-analysis, (ii) rapid environmental assessment (REA), (iii) two focus group discussions, (iv) the Delphi approach to determine priorities among major environmental threats. | 1. The study found that most displaced persons are located in climate change hot spots. 2. The initial phase of refugee settlement may expose victims to severe environmental impacts when proper planning is not done. 3. Loopholes in refugee protection laws encourage deforestation. 4. Camps are operated for decades without environmental impact assessment. |

| 11. | Suckall, N., Fraser, E., Forster, P., and Mkwambisi, D. (2015) [39]. Using a migration systems approach to understand the link between climate change and urbanisation in Malawi | Malawi | Climate change-rural-urbanization nexus | This quantitative study used in-depth interviews and focus group discussions to collect data on migration intentions. | 1. Climate change endangered both human and financial capital. 2. Environmental stressors decrease agricultural productivity which is a major source of income for people. 3. Access to information about urban opportunities is an important determinant of migrants. |

| 12. | Marchiori, L., Maystadt, J.-F., and Schumacher, I. (2012) [40]. The impact of weather anomalies on migration in Sub-Saharan Africa. | Sub-Saharan Africa. | Environmental factors influencing migration | This paper used a cross-country panel dataset to examine how weather anomalies increased internal and international migration between 1960 and 2000. | 1. Weather irregularities facilitate migration in agriculturally dependent countries. 2. Climate anomalies directly affect wages. 3. Climate anomalies intensify urbanization processes in countries dependent on agriculture. |

| 13. | Simatele, D., and Simatele, M. (2015) [10]. Migration as an adaptive strategy to climate variability: a study of the Tonga-speaking people of Southern Zambia. | Zambia | Migration as an adaptation strategy | This study used a participatory research methodology with 30 households conducting focus group discussions and in-depth interviews. | 1. The findings noted that extreme weather conditions significantly impacted participants’ involvement in agriculture. 2. Drought affected agriculture production and economic resources, contributing to migration. 3. Migration enablers such as social networks also facilitated participants’ movement. |

| 14. | Codjoe, S., Nyamedor, F. H., Sward, J., and Dovie, D. B. (2017) [41]. Environmental hazard and migration intentions in a coastal area in Ghana: a case of sea flooding. | Ghana | Environmental factors influencing migration intention | This paper used mixed methods: a household survey of 350 and 12 focus group discussions. | 1. Participants’ communities of residence and socio-economic capital are significant predictors of migration because of sea flooding. 2. Also, households with low economic resources and those without social capital have the highest migration index. 3. Finally, farmers are less likely to migrate, unlike skilled manual workers. |

| 15. | Suckall, N., Fraser, E., and Forster, P. (2017) [42]. Reduced migration under climate change: evidence from Malawi using an aspirations and capabilities framework. | Malawi | Reduced migration/immobility and climate change | This article used a mixed method approach: 225 surveys, 75 interviews, and 93 focus group discussions. | 1. Quantitative and qualitative data showed that most residents did not want to migrate. 2. However, the younger non-migrant cohort expressed the desire to migrate to experience city life. 3. Also, climatic conditions are likely to reduce socio-economic resources instigating migration, yet from the qualitative data, potential migrants possess high capital resources. |

| 16. | Call, M., and Gray, C. (2020) [43]. Climate anomalies, land degradation, and rural out-migration in Uganda. | Uganda | Environment factors influencing migration | This quantitative study used panel data from 850 Ugandan households with environmental data on soils, forests, and climate conditions. | 1. The result reveals that climate stressors, rather than land degradation, are the primary initiators of migration in Uganda. |

| 17. | Akinbami, C., A., O. (2021) [44]. Migration and Climate Change Impacts on Rural Entrepreneurs in Nigeria: A Gender Perspective. | Nigeria | climate change as a driver of migration/migration as an adaptation to climate change | A qualitative method of in-depth interviews and focus group discussions was used to solicit responses from respondents in selected rural areas in Nigeria under four different vegetation zones. | 1. The study reports differences in gender reactions to migration. 2. The study also discovered that climate change is a primary driver of migration as it affects livelihood activities differently in the various vegetation zones. |

| 18. | Bayar, M., and Aral, M. M. (2019) [45]. An Analysis of Large-Scale Forced Migration in Africa. | Africa | Non-environmental factors causing migration | This study conducts a quantitative analysis of 48 African countries from 2011–2017, to investigate the impact of forced migration. | 1. The findings indicate that violent conflicts, political unrest, and poverty are the primary causes of migration in Africa. 2. However, climate-induced migration indirectly affects migration while foreign aid fails to alleviate migration challenges. |

| 19. | Ng’ang’a, S. K., Bulte, E. H., Giller, K. E., McIntire, J. M., and Rufino, M. C. (2016) [46]. Migration and Self-Protection Against Climate Change: A Case Study of Samburu County, Kenya. | Kenya | Complementarity of migration and adaptation to climate shocks | The authors collected household data between February and May 2012, interviewing 500 households randomly from five locations; out of the 500 households, 139 of the households were ‘‘migrant households”. | 1. remittances are an important mechanism linking migration to livelihood activities in Kenya. 2. When faced with climatic anomalies, households adopt more rigorous measures such as purchasing drought-tolerant livestock. |

| 20. | Vinke, K., Rottmann, S., Gornott, C., Zabre, P., Nayna Schwerdtle, P., and Sauerborn, R. (2022) [12]. Is migration an effective adaptation to climate-related agricultural distress in sub-Saharan Africa? | Ivory Coast, Mali, Burkina Faso | Migration as an adaptation strategy | Two sets of interviews were carried out—one directed at migrants and the other directed at the migrant-sending community. A total of 52 semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted. | 1. The study found that while men migrated in the off-season, women stayed behind to take care of other activities. 2. Both male and female migrants see migration to have adverse socio-economic and health effects. However, the lack of options due to deteriorating environmental conditions forces the men to migrate. |

| 21. | Van Praag, L. (2021) [47]. Can I move or can I stay? Applying a life course perspective on immobility when facing gradual environmental changes in Morocco. | Morocco | Immobility in the context of climate change | The study uses 48 in-depth qualitative interviews conducted in Morocco between March and May 2018. | 1. From the findings, few respondents saw no urgent need to migrate in the light of slow-onset environmental stressors. 2. Instead, migration desires were related to societal changes and employment prospects. 3. Contrary, the older participants did not consider migrating since they were settled and had stronger economic and social capital. |

| 22 | Baada, J., N., Baruah, B., and Luginaah, I. (2021) [6]. Looming crisis-changing climatic conditions in Ghana’s breadbasket: the experiences of agrarian migrants. | Ghana | Environmental factors influencing migration | The authors conducted 30 in-depth interviews and five focused group discussions between September and December 2016. | 1. The findings revealed that changes in agricultural activities instigated migration intentions as agricultural returns are less. 2. Climate change impacts are unevenly distributed among rural agrarian regions since most migrant farmers have limited access to other sustainable farming methods. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ofori, D.O.; Bandauko, E.; Kutor, S.K.; Odoi, A.; Asare, A.B.; Akyea, T.; Arku, G. A Systematic Review of International and Internal Climate-Induced Migration in Africa. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152216105

Ofori DO, Bandauko E, Kutor SK, Odoi A, Asare AB, Akyea T, Arku G. A Systematic Review of International and Internal Climate-Induced Migration in Africa. Sustainability. 2023; 15(22):16105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152216105

Chicago/Turabian StyleOfori, Desmond Oklikah, Elmond Bandauko, Senanu Kwasi Kutor, Amanda Odoi, Akosua Boahemaa Asare, Thelma Akyea, and Godwin Arku. 2023. "A Systematic Review of International and Internal Climate-Induced Migration in Africa" Sustainability 15, no. 22: 16105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152216105

APA StyleOfori, D. O., Bandauko, E., Kutor, S. K., Odoi, A., Asare, A. B., Akyea, T., & Arku, G. (2023). A Systematic Review of International and Internal Climate-Induced Migration in Africa. Sustainability, 15(22), 16105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152216105