Theater-Based Interventions in Social Skills in Mental Health Care and Treatment for People with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To define the features of ASD.

- To review and compare experiences in the use of drama in people diagnosed with ASD.

- To justify the proposal to apply all kinds of theatrical techniques to people with ASD based on scientific evidence.

Problem Statement

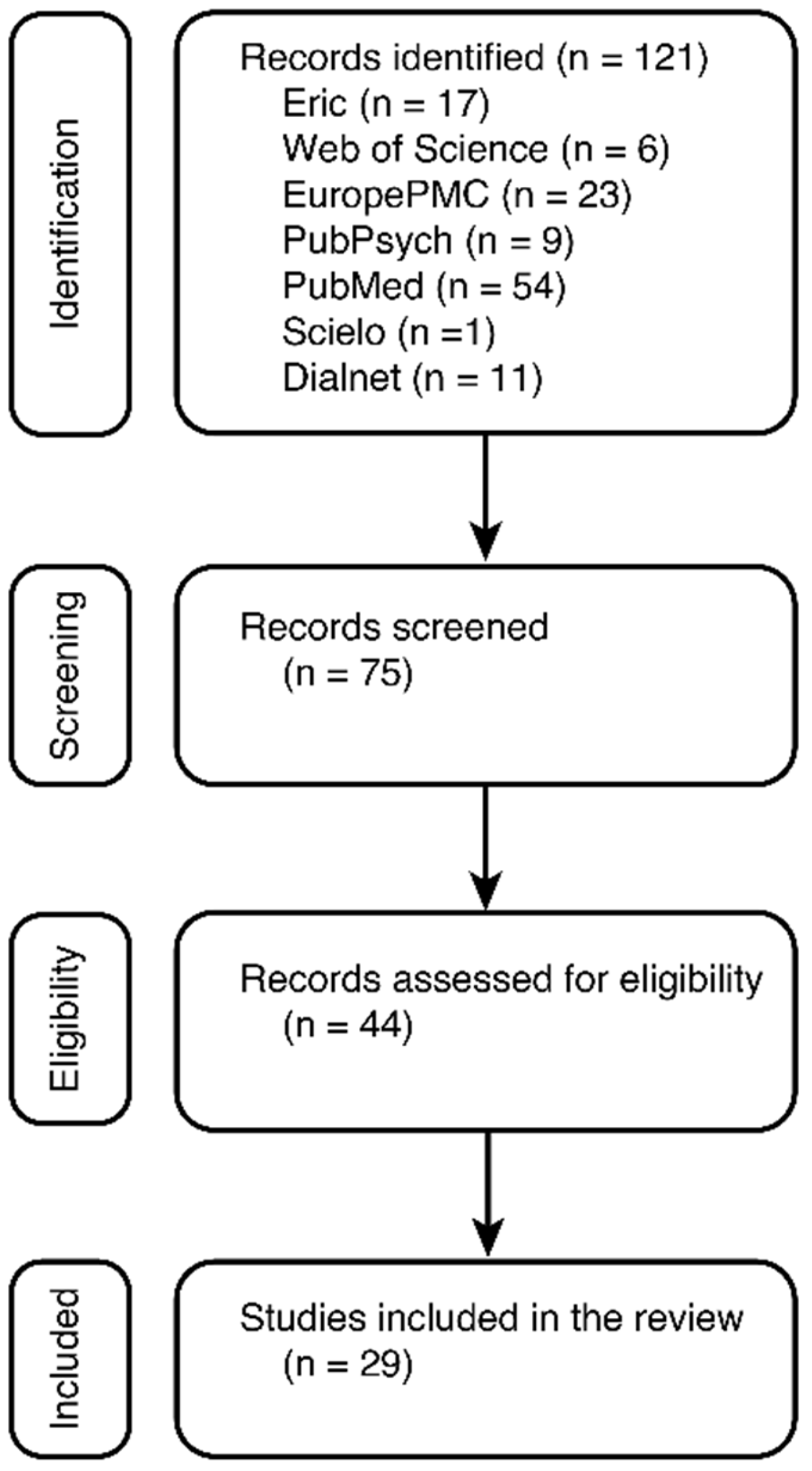

2. Methods

- -

- Theater and intervention and autism;

- -

- Dramatic art and autism;

- -

- Theater and autism spectrum;

- -

- Theater and asperger.

- -

- Teatro Y intervención Y autismo;

- -

- Arte dramático Y autismo;

- -

- Teatro Y espectro autista;

- -

- Asperger Y teatro.

- -

- Without the words (training/assistant/public/teachers);

- -

- Exact wording (autism spectrum).

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asociación Americana De Psiquiatría. Manual de Diagnóstico y Estadística de Trastornos Mentales, 5th ed.; Editorial Médica Panamericana: Arlington, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Merrell, K.W.; Gimpel, G.A. Social Skills of Children and Adolescents: Conceptualization, Assessment, Treatment; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ares, D.A.; Bermudez, L.M.; Chinchill, R.H. Neurodidáctica y estrategias de aprendizaje para la inclusión. Desarrollo de competencias comunicativas en niños y niñas con riesgo biológico y/o social. Rev. Educ. Inclusiva 2017, 9, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Otero, T.L.; Schatz, R.B.; Merrill, A.C.; Bellini, S. Social skills training for youth with autism spectrum disorders: A follow-up. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. 2015, 24, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D.M.; Esposito, M.K. Virtual reality in transition program for adults with autism: Self-efficacy, confidence, and interview skills. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 23, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, T.; Heinitz, K. Aspergers–different, not less: Occupational strengths and job interests of individuals with Asperger’s syndrome. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapp, S.K. Social support, well-being, and quality of life among individuals on the autism spectrum. Pediatrics 2018, 141 (Suppl. S4), S362–S368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhard, M.A.; Dewald-Kaufmann, J.; Wuestenberg, T.; Musil, R.; Barton, B.B.; Jobst, A.; Padberg, F. The vicious circle of social exclusion and psychopathology: A systematic review of experimental ostracism research in psychiatric disorders. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 270, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, C.; Blakemore, S.J.; Charman, T. Reactions to ostracism in adolescents with autism spectrum conditions. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2009, 39, 1122–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toseeb, U.; McChesney, G.; Oldfield, J.; Wolke, D. Sibling bullying in middle childhood is associated with psychosocial difficulties in early adolescence: The case of individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 1457–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Vázquez, A.R. Aprender a ver teatro, empezar a hacer teatro. Prim. Not. Rev. Lit. 2008, 233, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kempe, A.; Tissot, C. The use of drama to teach social skills in a special school setting for students with autism. Support Learn. 2012, 27, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, E.; Haythorne, D. Benefits of dramatherapy for autism spectrum disorder: A qualitative analysis of feedback from parents and teachers of clients attending roundabout dramatherapy sessions in schools. Dramatherapy 2013, 35, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, C. Drama and Autism. In Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders; Volkmar, F.R., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Conn, C. Play and Friendship in Inclusive Autism Education: Supporting Learning and Development; Routledge: Abingdon Oxon, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer, C.; Knorth, E.J.; Van Yperen, T.A.; Spreen, M. Exploring Change in Children’s and Art Therapists’ Behavior during ‘Images of Self’, an Art Therapy Program for Children Diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Repeated Case Study Design. Children 2022, 9, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanueva-Bonilla, C.; Bonilla-Santos, J.; Ríos-Gallardo, Á.M.; Solovieva, Y. Desarrollando habilidades emocionales, neurocognitivas y sociales en niños con autismo. Evaluación e intervención en juego de roles sociales. Rev. Mex. Neurocienc. 2018, 19, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, T.R.; Lerner, M.D.; Paterson, S.; Jaeggi, L.; Toub, T.S.; Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Golinkof, R. Stakeholder perceptions of the effects of a public school-based theatre program for children with ASD. J. Learn. Through Arts 2019, 15, n1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpella, M.; Evaggelinou, C.; Koidou, E.; Tsigilis, N. The effects of a theatrical play programme on social skills development for young children with autism spectrum disorders. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2019, 33, 828–845. [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez, L.M.M.; Poveda, A.S.; Rojas, V.G.; Ares, P.A. Teatro para convivir: Investigación-acción para el desarrollo de habilidades sociales en jóvenes costarricenses con trastorno del espectro autista. Rev. Esp. Discapac. 2019, 7, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, A.; DeNigris, D.; Gillespie-Lynch, K. Theatre as a tool to reduce autism stigma? evaluating ‘Beyond Spectrums’. Res. Drama Educ. J. Appl. Theatr. Perform. 2020, 25, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellavista-Rof, C.; Mora-Giral, M. Prevención y tratamiento de los trastornos mentales a través del teatro: Una revisión. Rev. Psicol. Clín. Con Niños Adolesc. 2019, 6, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, C. Improvisational theatre and occupational therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2021, 68, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, T.R. Correlations among social-cognitive skills in adolescents involved in acting or arts classes. Mind Brain Educ. 2011, 5, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, L.M. Intervención de teatro de sombras en un caso con necesidades educativas especiales por trastorno de espectro autista. Rev. Educ. Univ. Granada 2018, 25, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, B.A.; Ioannou, S.; Key, A.P.; Coke, C.; Muscatello, R.; Vandekar, S.; Muse, I. Treatment effects in social cognition and behavior following a theater-based intervention for youth with autism. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2019, 44, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, B.A.; Swain, D.M.; Coke, C.; Simon, D.; Newsom, C.; Houchins-Juarez, N.; Jenson, A.; Wang, L.; Song, Y. Improvement in social deficits in autism spectrum disorders using a theatre-based, peer-mediated intervention. Autism Res. 2014, 7, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fein, E. Making meaningful worlds: Role-playing subcultures and the autism spectrum. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 2015, 39, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, M.D.; Mikami, A.Y.; Levine, K. Socio-dramatic affective-relational intervention for adolescents with asperger syndrome & high functioning autism: Pilot study. Autism 2011, 15, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beadle-Brown, J.; Wilkinson, D.; Richardson, L.; Shaughnessy, N.; Trimingham, M.; Leigh, J.; Whelton, B.; Himmerich, J. Imagining autism: Feasibility of a drama-based intervention on the social, communicative and imaginative behaviour of children with autism. Autism 2018, 22, 915–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, N. Behold the tree: An exploration of the social integration of boys on the autistic spectrum in a mainstream primary school through a dramatherapy intervention. Dramatherapy 2017, 38, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.; Banerjee, S. An investigation of the therapeutic potential of stories in dramatherapy with young people with autistic spectrum disorder. Dramatherapy 2013, 35, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowsdale, J.; Hayhow, R. Psycho-physical theatre practice as embodied learning for young people with learning disabilities. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2015, 19, 1022–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Aguayo, S.; Pino-Juste, M. Trastornos del desarrollo y dramatización: Descripción de una experiencia teatral en un centro de Atención Temprana. In Atención Temprana y Educación Familiar, IV Congreso Internacional; Buceta, M.J., Crespo, J.M., Eds.; Servicio de Publicaciones e Intercambio Científico de la Universidade de Santiago de Compostela: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2015; pp. 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pimpas, I. A psychological perspective to dramatic reality: A path for emotional awareness in autism. Dramatherapy 2013, 35, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A.B.; Barreiros, J.M.R.; Sanmamed, M.G. El teatro como herramienta socializadora para personas con Asperger. Rev. Esp. Orientac. Psicopedag. 2016, 27, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Calafat-Selma, M.; Sanz-Cervera, P.; Tárraga-Mínguez, R. El teatro como herramienta de intervención en alumnos con trastorno del espectro autista y discapacidad intelectual. Rev. Educ. Inclusiva 2016, 9, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, B.A.; Blain, S.D.; Ioannou, S.; Balser, M. Changes in anxiety following a randomized control trial of a theatre-based intervention for youth with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2017, 21, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbett, B.A.; Gunther, J.R.; Comins, D.; Price, J.; Ryan, N.; Simon, D.; Schupp, C.W.; Rios, T. Brief report: Twiheatre as therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2011, 41, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guli, L.A.; Semrud-Clikeman, M.; Lerner, M.D.; Britton, N. Social competence intervention program (SCIP): A pilot study of a creative drama program for youth with social difficulties. Arts Psychother. 2013, 40, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, S. Autism and comedy: Using theatre workshops to explore humour with adolescents on the spectrum. Res. Drama Educ. J. Appl. Theatre Perform. 2017, 22, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehling, M.H.; Tassé, M.J.; Root, R. Shakespeare and autism: An exploratory evaluation of the Hunter Heartbeat Method. Res. Pract. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 4, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poveda, A.S.; Montoya, D.H. Digital fabrication and theater: Developing social skills in young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 615786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmer-Barbrook, C. Adolescence, Asperger’s and acting: Can dramatherapy improve social and communication skills for young people with Asperger’s syndrome? Dramatherapy 2013, 35, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelberg, J.; Frankel, F.; Cunningham, T.; Gorospe, C.; Laugeson, E.A. Long-term outcomes of parent-assisted social skills intervention for high-functioning children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 2014, 18, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada-Gañete, A.; Trillo-Alonso, F. Good Practices of Educational Inclusion: Criteria and Strategies for Teachers’ Professional Development. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtayermman, O. Peer victimizationin adolescents and young adultsdiagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome: A link to depressive symptomatology, anxiety symptomatology and suicidalideation. Issues Compr. Pediatr. Nurs. 2007, 30, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shtayermman, O. An exploratorystudy of the stigma associatedwith a diagnosis of Asperger’ssyndrome: The mental health impacton the adolescents and young adultsdiagnosed with a disability witha social nature. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2009, 19, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors and Year | Type of Intervention | Sessions/Duration | Sample | Results | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beadle-Brown et al. [32] | Multisensory capsule improvisation games | 10/45 min sessions, 1 weekly/10 weeks | 22 individuals with ASD (7–12 years old) | Development of social interaction, communication, and imagination. | 0.8 |

| Martínez et al. [38] | Weekend extracurricular theater workshop | 6 of 1 h and 30 min 1 fortnightly/12 weeks | 7 individuals with Asperger’s (14–18 years old) | Increased social skills, sense of belonging to a group, improved self-esteem, empathy, and listening skills. | NR |

| Calafat-Selma et al. [39] | Extracurricular theater | 27/50 min sessions, 2 weekly/16 weeks | 2 individuals with ASD and 7 with intellectual disability | Improvements in speech, relationship, and play. Adaptation level without significant improvement. | NR |

| Corbett et al. [41] | Theatrical intervention program | 38/2 h sessions, 4 weekly/12 weeks | 8 individuals with ASD and 8 normotypical individuals (6–17 years old) | Improved social–emotional functioning. | NR |

| Corbett et al. [29] | Summer camp | 10/4 h sessions, 5 weekly/2 weeks | 11 individuals with ASD and Asperger’s (8–17 years old) | Increased active participation with peers. Improved facial identification and memory. | NR |

| Corbett et al. [40] | Weekend theater workshop | 10/4 h sessions, 1 weekly/10 weeks | 30 individuals with ASD and 30 normotypical individuals (8–14 years old) | Decrease in stress and anxiety. | NR |

| Corbett et al. [28] | Weekend theater workshop for young people | 10/4 h sessions, 1 weekly/10 weeks | 77 individuals with ASD (8–16 years old) | Improvements in theory of mind, facial memory, and cooperative gameplay. | NR |

| Fein [30] | Theater workshop, at summer camp | NR | Individuals with ASD (11–18 years old) | Improved personal relationships. | NR |

| Fernández-Aguayo and Pino-Juste [36] | Theatrical exercises in an early care center | 16/1 h and 10 min sessions, 1 weekly/16 weeks | 9 ASD/social communication disorder/cognitive deficiency (3–4 years old) | Increased communication. Improved identification and representation of emotions. Ability to develop conversations. | NR |

| Godfrey and Haythorne [14] | Dramatherapy program in various contexts | NR | 42 family members, educators, and teachers of students with ASD | Increased confidence, self-esteem, social skills, communication skills, creativity, and imagination. | NR |

| Goldstein et al. [19] | Musical theater in a special-education center | 40 sessions throughout the school year | 36 individuals with ASD (3–12 years old) | Improved social relations and behavioral skills. | NR |

| Guli et al. [42] | Creative theater workshop | 12/2 h session, 1 weekly/12 weeks 16/1.5 h sessions, 2 weekly/8 weeks | 11 individuals with ASD, 2 with nonverbal learning disability and 5 with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (8–14 years old) | Improved interpersonal relationships. Increased empathy and self-control. | NR |

| Kempe and Tissot [13] | Intervention program in a special-education center | 13/1 h and 40 min sessions over 20 weeks | 10 individuals with learning difficulties and 2 with ASD (18–19 years old) | Increase in social skills. Development of creative skills. | NR |

| Lerner et al. [31] | Sociodramatic intervention based on improvisation in a summer program | 29/5 h sessions, 1 daily/6 weeks | 17 individuals with Asperger’s and high-functioning individuals with ASD (11–17 years old) | Improved social skills. | NR |

| Lewis and Banerjee [34] | Storytelling in drama therapy at a special education school | 12/60 min sessions, 10 group and 2 individual sessions/12 weeks | 3 individuals with ASD (12–14 years old) | Increased security, confidence, self-esteem, insight, and empathy. | NR |

| Bermúdezz et al. [21] | Theater workshop for young people | 95/1.5 h sessions, 1 weekly/95 weeks | 8 individuals with ASD (12–22 years old) | Increased emotional expression and assertive communication. | NR |

| Mandelberg et al. [47] | Social skills program | 12/1 h sessions, 1 weekly/12 weeks | 24 high-functioning individuals with ASD and normotypical peers (6–11 years old) | Reduction in conflicts in the game. Improved emotional management. | NR |

| Martínez [27] | Shadow theater in an early care center | 30/50 min sessions, 3 weekly/10 weeks | 1 individual with ASD (6 years old) | Improved communicative intent and emotional state. Increased body awareness. | NR |

| Massa et al. [22] | Theatrical production | 2 months | 2 individuals with ASD, 1 with anxiety disorder (18-29 years old) | Reduction in autism stigma. | NR |

| May [43] | Comedy and clown workshops | NR | 5 individuals with ASD and 4 normotypical individuals (13–16 years old) | Myth of autistic humorlessness debunked. | NR |

| Mehling et al. [44] | Extracurricular theater workshop | 10/1 h sessions, 1 weekly/10 weeks | 14 individuals with ASD (10–13 years old) | Improved social interaction, pragmatic language, and facial emotional recognition. | NR |

| Mpella et al. [20] | Theater program as part of the school’s physical education program | 16/45 min sessions, 2 weekly/8 weeks | 6 individuals with ASD and 132 normotypical peers in their respective classrooms (9–11 years old). | Improved cooperation, attention, and empathy. Reduction in anxiety and repetitiveness. | NR |

| Dyer [33] | Dramatherapy in elementary school | 8/45 min sessions, 1 weekly/8 weeks | 3 individuals with ASD and 3–5 normotypical individuals (5–11 years old) | Increased confidence and self-esteem. Improved turn-taking and skills to work effectively alone and with others. | NR |

| O’Sullivan [15] | Weekend dramatherapy workshop | 10/90 min sessions, 1 weekly/10 weeks | 12 individuals with Asperger’s (9–11 years old) | High levels of activity and interest. Emotional and physical collapse of a participant. | NR |

| Pimpas [37] | Social skills training program | 1/45 min session, 1 weekly/1 year | 1 individual with ASD (9 years old) | Correct display of emotions and affections. Greater expressiveness. | NR |

| Poveda and Montoya [45] | Theater and digital fabrication workshop | 16/1.5 h sessions, 1 weekly/16 weeks | 10 individuals with ASD (12–20 years old) | Improvements in the expression of emotions and teamwork. | NR |

| Trowsdale and Hayhow [35] | Psychophysical theater during school hours in a special education center | 1/1 h session, 1 weekly/5 years | Variety of students with learning difficulties, ASD, among others (3–11 years old) | Improved communication and socialization skills. New collaboration skills. | NR |

| Villanueva-Bonilla et al. [18] | Social role play | 25/60 min sessions, 2 weekly/13 weeks | 3 individuals with ASD (8–10 years old) | Positive changes in identification, understanding, and emotional expression. | NR |

| Wilmer-Barbrook [46] | Dramatherapy | 36/1.5 h sessions, 1 weekly/36 weeks | 8 individuals with Asperger’s (16–24 years old) | Increased confidence, self-esteem, social skills, emotional expression, and communication skills. | NR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martí-Vilar, M.; Fernández-Gómez, N.; Hidalgo-Fuentes, S.; González-Sala, F.; Merino-Soto, C.; Toledano-Toledano, F. Theater-Based Interventions in Social Skills in Mental Health Care and Treatment for People with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316480

Martí-Vilar M, Fernández-Gómez N, Hidalgo-Fuentes S, González-Sala F, Merino-Soto C, Toledano-Toledano F. Theater-Based Interventions in Social Skills in Mental Health Care and Treatment for People with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2023; 15(23):16480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316480

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartí-Vilar, Manuel, Nuria Fernández-Gómez, Sergio Hidalgo-Fuentes, Francisco González-Sala, César Merino-Soto, and Filiberto Toledano-Toledano. 2023. "Theater-Based Interventions in Social Skills in Mental Health Care and Treatment for People with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review" Sustainability 15, no. 23: 16480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316480

APA StyleMartí-Vilar, M., Fernández-Gómez, N., Hidalgo-Fuentes, S., González-Sala, F., Merino-Soto, C., & Toledano-Toledano, F. (2023). Theater-Based Interventions in Social Skills in Mental Health Care and Treatment for People with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 15(23), 16480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316480