Analyzing Community Perception of Protected Areas to Effectively Mitigate Environmental Risks Using Qualitative Comparative Analysis: The Case of Savu Sea National Marine Park, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

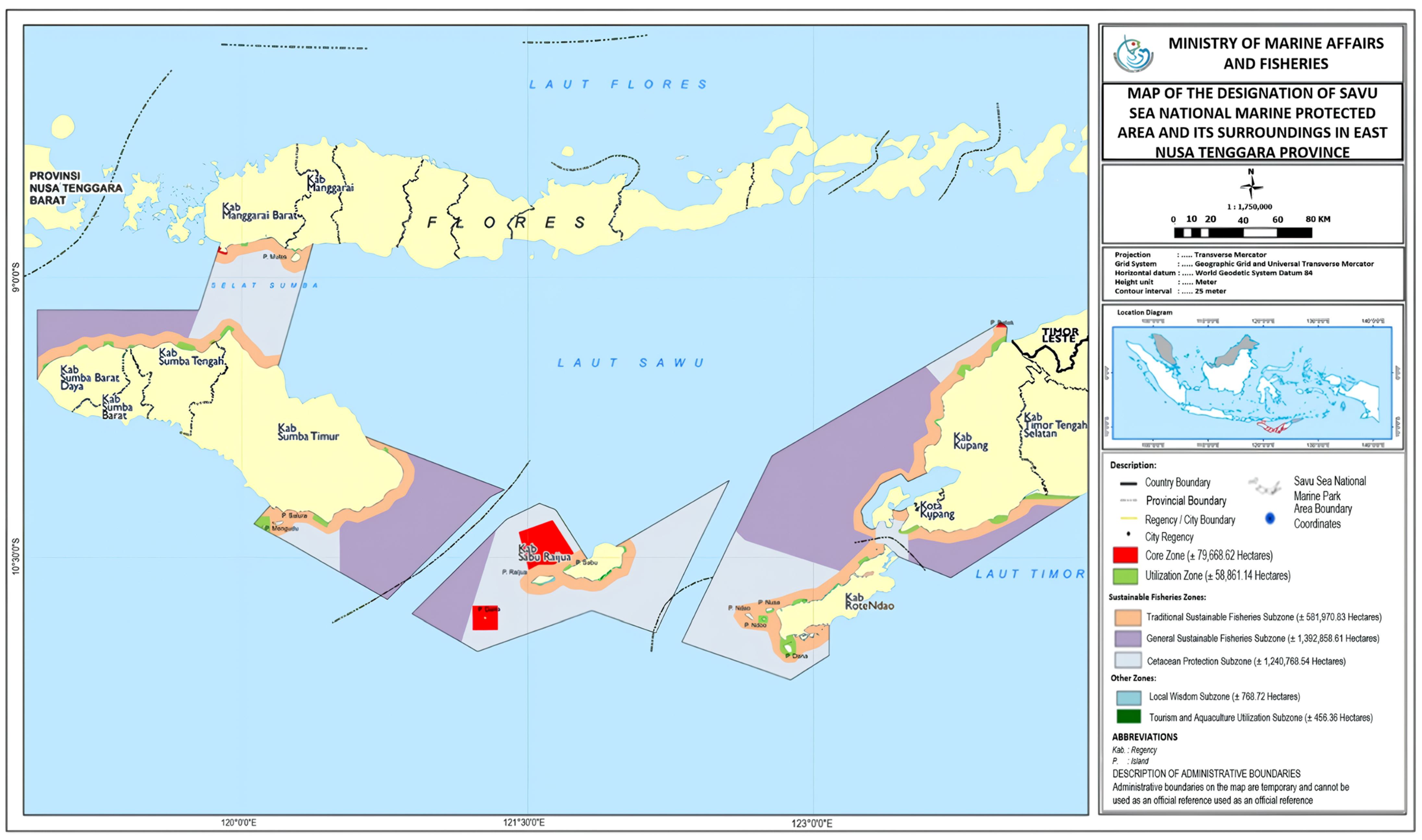

2. Brief Description of the Savu Sea

2.1. When Was the Savu Sea NMP Established and Why?

- (1)

- The establishment of the Savu Sea NMP

- (2)

- The purpose of establishing the Savu Sea NMP

2.2. Management Authorities

2.3. The Role of the Savu Sea NMP in Ecology, Economy, and Society

- (1)

- Ecology

- (2)

- Economy and Society

3. Materials and Methods

- The socio-economic condition of coastal households around the Savu Sea (social).

- Environmental awareness (awareness).

- The existence of a conservation area for the community (existence).

- Attitudes towards activities (permitted or not permitted) in the conservation area (activity).

- The involvement of participation in multi-stakeholder institutions (participation).

- Located in the Savu Sea NMP.

- A majority of the population engaged in marine resource extraction for both economic and livelihood purposes.

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Suraji, R.P.; Rahayu, S.; Yusra, D.L.; Darwis, A.; Ashari, M.; Sifiullah, A. Mengenal Potensi Kawasan Konservasi Perairan Nasional: Profil Kawasan Konservasi Perairan Nasional (Discover the Potential of National Marine Protected Areas: Profile of National Marine Protected Areas); Directorate of Conservation of Fish Areas and Species: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2010; pp. 22–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, B.; (APEX Environmental, Ross, CA, USA). Unpublished work, 2005.

- Mustika, P.L.K. Marine Mammals in the Savu Sea (Indonesia): Indigenous Knowledge, Threat Analysis and Management Options. Masters’s Thesis, James Cook University, Douglas, QLD, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Purba, N.P.; Ihsan, Y.N.; Faizal, I.; Handyman, D.I.W.; Widiastuti, K.S.; Mulyani, P.G.; Tefa, M.F.; Hilmi, M. Distribution of macro debris in Savu Sea Marine National Park (Kupang, Rote, and Ndana Beaches), East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia. World News Nat. Sci. 2018, 21, 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Gall, S.C.; Thompson, R.C. The impact of debris on marine life. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 92, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifton, J. Science, funding and participation: Key issues for marine protected area networks and the Coral Triangle Initiative. Environ. Conserv. 2009, 36, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.; Rudyanto, F.; Agung, M.F.; Minarputri, N.; Lestari, A.P.; Wen, W.; Fajariyanto, Y.; Green, A.; Tighe, S. Marine protected area networks in Indonesia: Progress, lessons and a network design case study covering six eastern provinces. Coast. Manag. 2021, 49, 575–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, M.M. New Consensus on Archipelagic Sea Lane Passage Regime over Marine Protected Areas: Study Case on Indonesian Waters. In Proceedings of the Asian Conference on the Social Sciences 2017, Kobe, Japan, 8–11 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- He, Q.; Silliman, B.R. Climate change, human impacts, and coastal ecosystems in the Anthropocene. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R1021–R1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soemodinoto, A.; Pedju, M. Evaluability assessment of Indonesian marine conservation areas for management effectiveness evaluation. Indones. J. Mar. Sci. 2022, 27, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, C.; Díaz, D.; Fietz, K.; Forcada, A.; Ford, A.; García-Charton, J.A.; Goñi, R.; Lenfant, P.; Mallol, S.; Mouillot, D.; et al. Reviewing the ecosystem services, societal goods, and benefits of marine protected areas. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 613819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroeker, K.J.; Carr, M.H.; Raimondi, P.T.; Caselle, J.E.; Washburn, L.; Palumbi, S.R.; Barth, J.A.; Chan, F.; Menge, B.A.; Milligan, K.; et al. Planning for change: Assessing the potential role of marine protected areas and fisheries management approaches for resilience management in a changing ocean. Oceanography 2019, 32, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Franco, A.; Thiriet, P.; Di Carlo, G.; Dimitriadis, C.; Francour, P.; Gutiérrez, N.L.; de Grissac, A.J.; Koutsoubas, D.; Milazzo, M.; Otero, M.D.M.; et al. Five key attributes can increase marine protected areas performance for small-scale fisheries management. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, W.B.; Ferse, S.C.A. Indonesia Case Study: Let Us Get Political: Challenges and Inconsistencies in Legislation Related to Community Participation in the Implementation of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in Indonesia; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, C.A.; Azmanajaya, E. Socio-economic assessment of coastal communities in East Flores marine reserves of East Nusa Tenggara province, Indonesia. Russ. J. Agric. Socio-Econ. Sci. 2020, 97, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, M.H.; White, J.W.; Saarman, E.; Lubchenco, J.; Milligan, K.; Caselle, J.E. Marine protected areas exemplify the evolution of science and policy. Oceanography 2019, 32, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Dearden, P. Why local people do not support conservation: Community perceptions of marine protected area livelihood impacts, governance and management in Thailand. Mar. Policy 2014, 44, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkness, P.L. Reconciling Conservation and Development Interests for Coastal Livelihoods: Understanding Foundations for Small-Scale Fisheries Co-Management in Savu Raijua District, Eastern Indonesia. Doctoral Dissertation, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Turisno, B.E.; Mahmudah, S.; Ganggasant, D.I.G.A.; Soemarmi, A. Considerations of local wisdom from Sabu Raijua Regency (Indonesia) for coral reef conservation for responsible management measures. Int. J. Oceanogr. Aquac. 2023, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, D. Konservasi mamalia laut (Cetacea) di perairan Laut Sawu Nusa Tenggara Timur (Conservation of marine mammals (Cetaceans) in the Savu Sea waters of East Nusa Tenggara). Jurnal Kelautan 2011, 4, 24–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, B.; Yusuf, F. Rapid Ecological Assessment (REA) for Cetaceans in the Savu Sea Marine National Park; The Nature Conservancy Indonesia Coasts and Oceans Program: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2014; pp. 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ihsan, R.A.A.I. TNP Laut Sawu “Home of The Cetacean”; Balai Kawasan Konservasi Perairan Nasional Kupang: Kupang, Indonesia, 2020; pp. 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Zamani, N.P.; Madduppa, H.H. A standard criteria for assessing the health of coral reefs: Implication for management and conservation. J. Indones. Coral Reefs 2011, 1, 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, F.; Selvaggia, S.; Scowcroft, G.; Fauville, G.; Tuddenham, P. Ocean Literacy for All: A Toolkit; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2017; pp. 16–51. [Google Scholar]

- Achmad, A.; Munasik, M.; Wijayanti, D.P. Kondisi ekosistem terumbu karang di Rote Timur, Kabupaten Rote Ndao, Taman Nasional perairan Laut Sawu menggunakan metode manta tow (Coral reef ecosystem condition in East Rote, Rote Ndao Regency, Savu Sea waters National Park using manta tow method). J. Mar. Res. 2013, 2, 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries Republic of Indonesia. Profile TNP Laut Sawu. Available online: https://kkp.go.id/djprl/bkkpnkupang/page/352-profil-tnp-laut-sawu (accessed on 13 July 2023).

- Ragin, C.C. The Comparative Method: Moving beyond Qualitative and Quantitative Strategies; University of California Press: London, UK, 1987; pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Verweij, S.; Trell, E.M. Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) in spatial planning research and related disciplines: A systematic literature review of applications. J. Plan. Lit. 2019, 34, 300–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihoux, B.; Ragin, C.C. Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Related Techniques; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.Q.; Wagemann, C. Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences: A Guide to Qualitative Comparative Analysis; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Legewie, N. An introduction to applied data analysis with qualitative comparative analysis. FQS 2013, 14, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Roig-Tierno, N.; Ginzalez-Cruz, T.F.; Llopis-Martinez, J. An overview of qualitative comparative analysis: A bibliometric analysis. J. Innov. Knowl. 2017, 2, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosamu, I.B.M. Conditions for sustainability of small-scale fisheries in developing countries. Fish. Res. 2015, 161, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.; Reutter, M.; Matzdorf, B.; Sattler, C.; Schomers, S. Design rules for successful governmental payments for ecosystem services: Taking agri-environmental measures in Germany as an example. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 157, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Koppenjan, J.; Verweij, S. Governing environmental conflicts in China: Under what conditions do local government compromise? Public Adm. 2016, 94, 806–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, T.C.; Federo, R. Qualitative Comparative Analysis: Qualitative comparative analysis: Justifying a neo-configurational approach in management research. RAUSP Manag. J. 2019, 54, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunce, L.; Pomeroy, B. Socioeconomic Monitoring Guidelines for Coastal Managers in Southeast Asia: SOCMON SEA; World Commission on Protected Areas and Australian Institute of Marine Science: Darwin, NT, Australia, 2003; pp. 7–82. [Google Scholar]

- Widodo, H.; Carter, E.; Welly, M.; Sofyanto, H.; Fajaruddin; Silvia, N.; Arifudin, L.O.; Korebima, M.; Saleh, R.; Tomasouw, J.; et al. Perception Monitoring Protocol 2009: General Protocol for The Implementation of Perception Monitoring Program at TNC-CTC’s Marine Conservation Sites and Partners in Indonesia; The Nature Conservancy Indonesia Program Coral Triangle Center: Bali, Indonesia, 2009; pp. 4–35. [Google Scholar]

- Setiyowati, D.; Ayub, A.F.; Zulkifli, M. Statistics of Marine and Coastal Resources; BPS-Statistic Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2016; pp. 31–117. [Google Scholar]

- Tosmana. Tool for Small-N Analysis (Version 1.61). Available online: https://www.tosmana.net (accessed on 27 August 2023).

- Nuka, F.M. Kelompok Warga di Manggarai Barat Telah Melepas 1.800 Penyu Sejak 2021 (Community Groups in West Manggarai Have Released 1800 Sea Turtles Since 2021). ANTARA News. 8 January 2023. Available online: https://www.antaranews.com/berita/3340734/kelompok-warga-di-manggarai-barat-telah-melepas-1800-penyu-sejak-2021 (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Oktavia, P.; Wilmar, S.; Glaudy, P. Reinventing Papadak/Hoholok as a traditional management system of marine resources in Rote Ndao, Indonesia. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 161, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regional Government of Sabu Raijua Regency. Regent Regulation 3/25 August 2011; Regional Government of Sabu Raijua Regency. Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/55750/perda-kab-sabu-raijua-no-3-tahun-2011 (accessed on 7 September 2023).

- Xu, K.; Wu, W. Geoparks and geotourism in China: A sustainable approach to geoheritage conservation and local development—A review. Land 2022, 11, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Lu, S.; Zhu, Y. Research on popular science tourism based on SWOT-AHP model: A case study of Koktokay World Geopark in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Franco, G.; Montalván-Burbano, N.; Carrión-Mero, P.; Jaya-Montalvo, M.; Gurumendi-Noriega, M. Worldwide research on geoparks through bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, J.C.; Vale, T.F.D.; Burns, R.C. Fernando de Noronha Archipelago (Brazil): A coastal geopark proposal to foster the local economy, tourism and sustainability. Water 2021, 13, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizal, A.; Riyadi, A.; Haryanti; Aliah, R.S.; Prayogo, T.; Prayitno, J.; Purwanta, W.; Susanto, J.P.; Sofiah, N.; Djayadihardja, Y.S.; et al. Development of sustainable coastal benchmarks for local wisdom in Pangandaran village communities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, C.; McCartney, M.; Tickner, D.; Harrison, I.J.; Pacheco, P.; Ndhlovu, B. Evaluating the global state of ecosystems and natural resources: Within and beyond the SDGs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbwae, I.; Aswani, S.; Sauer, W.; Hay, C. Transboundary fisheries management in Kavango–Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA-TFCA): Prospects and dilemmas. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarto, R.H.; Sumartono, S.; Muluk, M.R.K.; Nuh, M. Penta-helix and quintuple-helix in the management of tourism villages in Yogyakarta City. Australas. Account. Bus. Finance J. 2020, 14, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, T. A review on Penta helix actors in village tourism development and management. J. Bus. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 5, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadaro, I.; Pirlone, F.; Bruno, F.; Saba, G.; Poggio, B.; Bruzzone, S. Stakeholder participation in planning of a sustainable and competitive tourism destination: The Genoa Integrated Action Plan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhammar, H.; Li, W.; Molina, C.M.M.; Hickey, V.; Pendry, J.; Narain, U. Framework for sustainable recovery of tourism in protected areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahyah; Tokan, M.K. Characteristics of the outermost small islands in East Nusa Tenggara Province Indonesia. Int. J. Oceans Oceanogr. 2015, 9, 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sunyowati, D.; Adam, H.; Vinata, R.T. The principles of uti possidetis juris as an alternative to settlement determination of territorial limits in the Oecussi sacred area (Study of the NKRI and RDTL boundaries). Yuridika 2019, 34, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauro, A.; Ojeda, J.; Caviness, T.; Moses, K.P.; Moreno-Terrazas, R.; Wright, T.; Zhu, D.; Poole, A.K.; Massardo, F.; Rozzi, R. Field environmental philosophy: A biocultural ethic approach to education and ecotourism for sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stålhammar, S.; Brink, E. ‘Urban biocultural diversity’ as a framework for human–nature interactions: Reflections from a Brazilian favela. Urban Ecosyst. 2021, 24, 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, A.C. Living with the land ethic. Bioscience 2004, 54, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibawa, K.C.S.; Saraswati, R.; Ispriyarso, B. Conflicts, law enforcement and the preservation of culture in the traditional communities: The Pasola ritual in Wanukaka in West Sumba in Indonesia. ISVS 2023, 10, 206–223. [Google Scholar]

- Sihombing, L.H.; Aninda, M.P. Bloodshed and meaning for the life of the Sumbanese in the Pasola tradition. Al-Hikmah Media Dakwah Komun. Sos. Dan Kebud. 2022, 13, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriadi; Siagian, V.P.Y.; Nurisnaeny, P.S. Kampung Bahari Nusantara as an alternative for multi-sector development of a village. Int. Rev. Humanit. Stud. 2022, 7, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, E.; Brian, S.; Rodney, S. Sasi and marine conservation in Raja Ampat, Indonesia. Coast. Manag. 2009, 37, 656–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haulussy, R.R.; Najamuddin; Idris, R.; Agustang, A.D.M.P. The sustainability of the Sasi Lola tradition and customary law (Case study in Masawoy Maluku, Indonesia). Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 9, 5193–5195. [Google Scholar]

- Subekti, P.; Budiana, H.R. The Role of Sasi as a Local Wisdom Based Environmental Sustainability. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Life, Innovation, Change and Knowledge (ICLICK 2018), Bandung, Indonesia, 18–19 July 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkes, I.; Novaczek, I. Presence, performance, and institutional resilience of sasi, a traditional management institution in Central Maluku, Indonesia. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2002, 45, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feruzia, S.; Satria, A. Sustainable coastal resource co-management. In WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, 1st ed.; Pineda, F.D., Brebbia, C.A., Garcia, J.L.M.I., Eds.; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2016; Volume 201, pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Fidler, R.Y.; Ahmadia, G.N.; Amkieltiela; Awaludinnoer; Cox, C.; Estradivari; Glew, L.; Handayani, C.; Mahajan, S.L.; Mascia, M.B.; et al. Participation, not penalties: Community involvement and equitable governance contribute to more effective multiuse protected areas. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabl8929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Village | Social | Awareness | Existence | Activity | Participation | Perception |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benteng Dewa | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Nanga Lili | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Nanga Bere | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Nuca Molas | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Terong | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Setar Ruwuk | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Setar Lenda | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Londa Lusi | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Namodale | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Tesabela | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Nuse | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Loborai | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Mebba | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Raemedia | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Letekonda | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Lokori | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Lenang | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Tablolong | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sulamu | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| South Netemnanu | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| North Netemnanu | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Buraen | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Village | Social | Awareness | Existence | Activity | Participation | Perception |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setar Ruwuk | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| North Netemnanu | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Terong | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Setar Lenda | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Namodale, Tesabela | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Loborai, South Netemnanu | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Mebba, Raemedia | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Buraen | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nuca Molas, Lokori | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Letekonda | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sulamu | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Nuse | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Nanga Bere, Londa Lusi, Lenang | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Benteng Dewa, Nanga Lili, Tablolong | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paulus, C.A.; Fauzi, A.; Adar, D. Analyzing Community Perception of Protected Areas to Effectively Mitigate Environmental Risks Using Qualitative Comparative Analysis: The Case of Savu Sea National Marine Park, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316498

Paulus CA, Fauzi A, Adar D. Analyzing Community Perception of Protected Areas to Effectively Mitigate Environmental Risks Using Qualitative Comparative Analysis: The Case of Savu Sea National Marine Park, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia. Sustainability. 2023; 15(23):16498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316498

Chicago/Turabian StylePaulus, Chaterina Agusta, Akhmad Fauzi, and Damianus Adar. 2023. "Analyzing Community Perception of Protected Areas to Effectively Mitigate Environmental Risks Using Qualitative Comparative Analysis: The Case of Savu Sea National Marine Park, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia" Sustainability 15, no. 23: 16498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316498