The Well-Being-Related Living Conditions of Elderly People in the European Union—Selected Aspects

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- The ageing of populations is one of the main demographic problems.

- This problem applies to highly developed European countries in particular.

- This problem is not taking place equally in all countries and has a different impact on their socio-economic development.

2. Literature Review

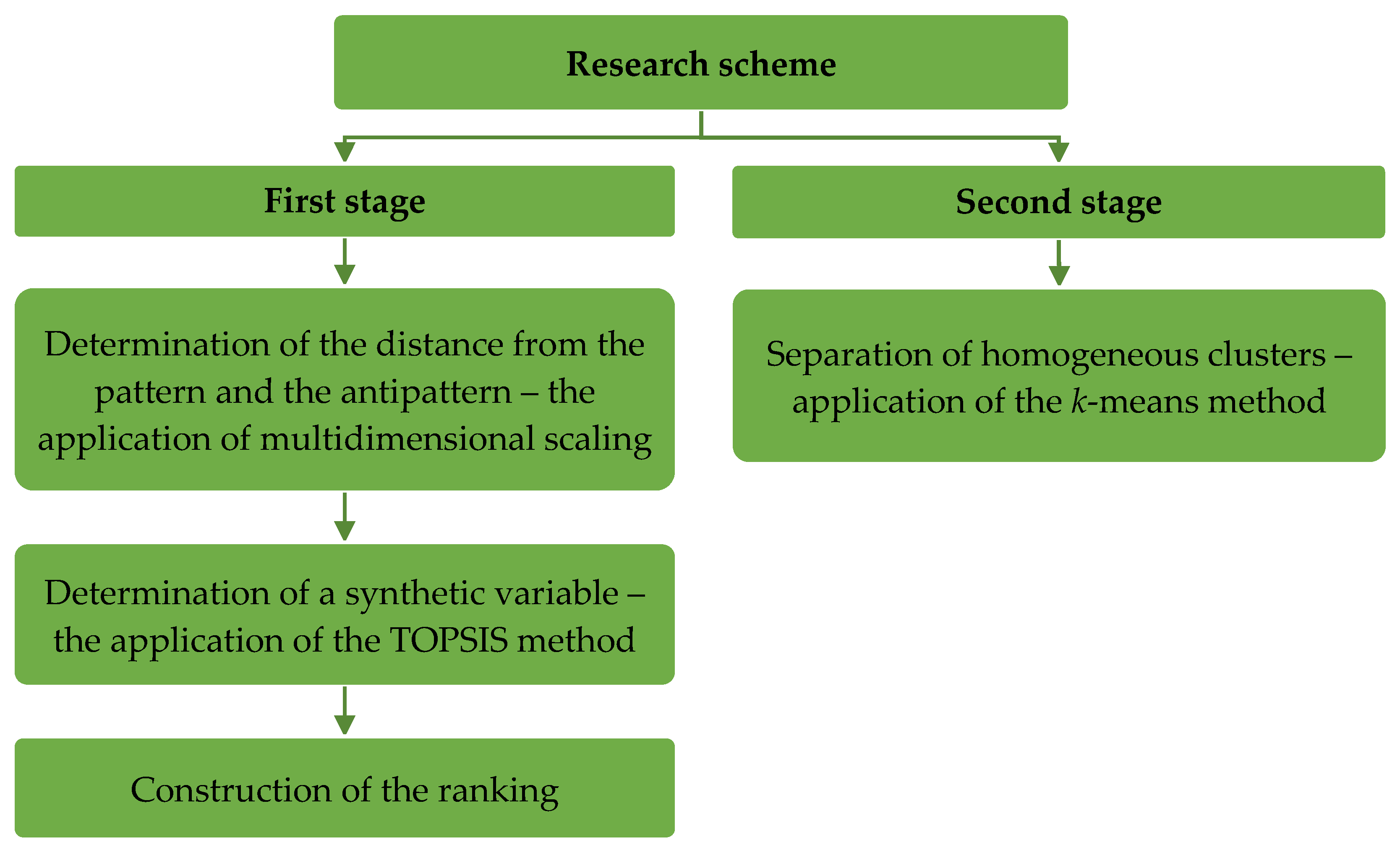

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Multidimensional Scaling

- Classic (metric) multidimensional scaling (cMDS), also called main coordinate analysis (PCoA)

- Non-metric multidimensional scaling (nMDS)

- Generalised multidimensional scaling (GMD)

- xij—value of j-th variable in i-th object (i = 1, …, n, j = 1, …, m)

- m—number of variables

- n—number of objects

- zij—normalised value of j-th variable in i-th object (i = 1, …, n, j = 1, …, m)

- We calculated the distance matrix between the objects δ for the m-dimensional space by means of the Euclidean metric.

- We mapped the distance matrix δ to the matrix d for the q-dimensional space (q < m). In order to represent the results of multidimensional scaling graphically, q = 2.

- We calculated the loss of information when mapping a distance matrix in m-dimensional space to a distance matrix in q-dimensional space (stress) using the following formula:

3.2. Application of the TOPSIS Method

- —the distance of the i-th country from the antipattern

- —the distance of the i-th country from the pattern

3.3. The K-Means Method

- We created the observation matrix X.

- We normalised the data.

- We divided the set of objects into s clusters (s = 1, …, k, …, n).

- We calculated the centre of gravity in every cluster (centroid) and the distance of every object from it.

- We changed the assignment of objects to clusters with the closest centroid.

- We calculated the new centroids.

- We repeated steps 5–6 until the next relocation of objects ceased to improve the general distances of objects from the centroids.

- We repeated steps 4–7 for various numbers of clusters.

- P = {P1, …, Pk}—set of homogeneous clusters

- —distance of the i-th object from the centroid for the s-th cluster

- —centroid for the s-th cluster

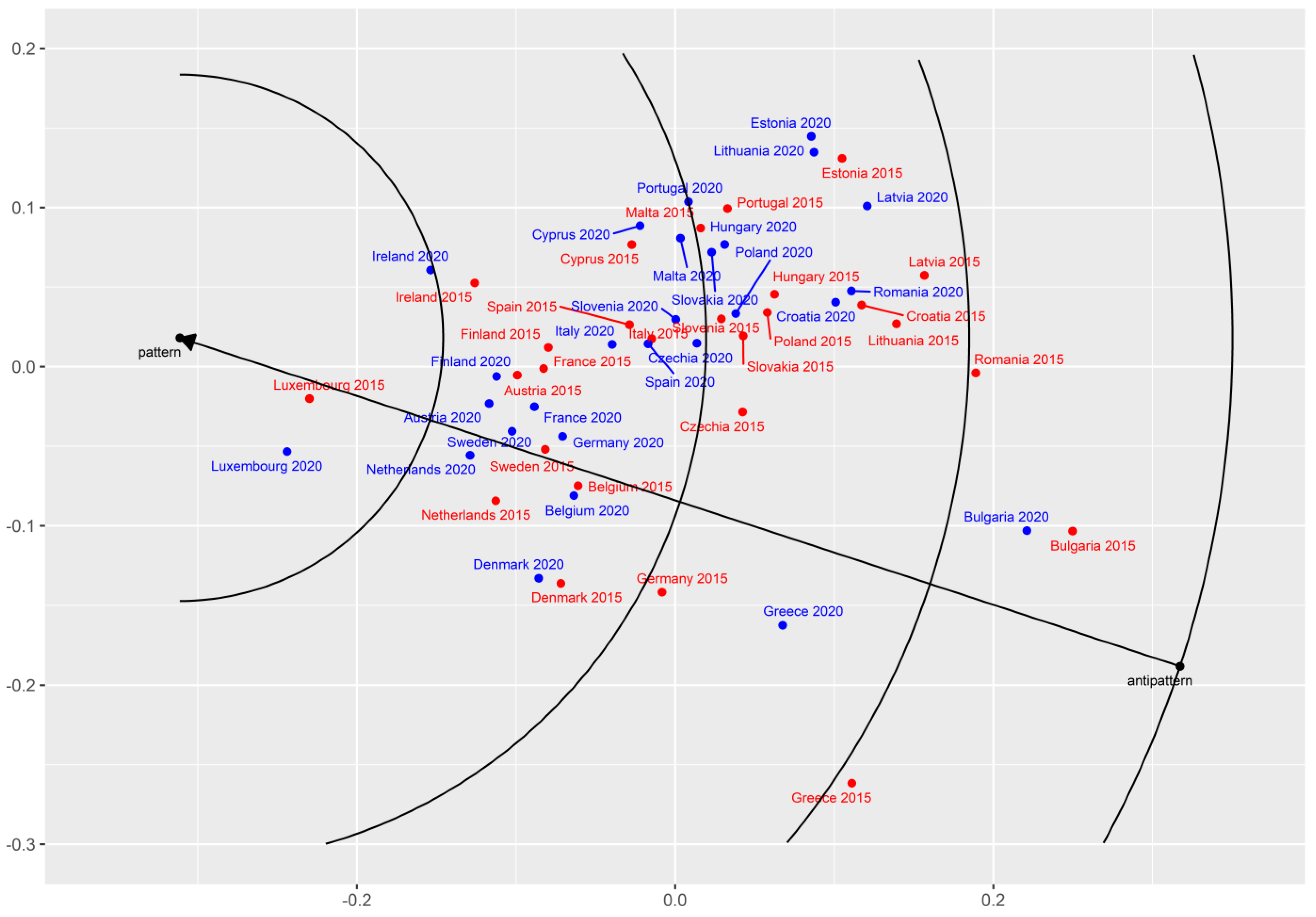

- For the years 2015 and 2020, we applied multidimensional scaling to represent the distances between the EU countries with respect to the well-being-related living conditions of elderly people.

- Using the TOPSIS formula, we created the rankings of EU member states with regard to the well-being-related living conditions of elderly people in the years 2015 and 2020.

- By using the k-means method, we distinguished the homogeneous clusters of the EU countries with respect to the well-being-related living conditions of elderly people.

- We analysed the mean values of indicators in the clusters for the years 2015 and 2020.

4. Results

4.1. Graphical Representation of Distances between the EU Countries in 2015 and 2020

4.2. Rankings of EU Countries

4.3. Cluster Analysis

- The first cluster (marked in orange): the Baltic States, Bulgaria, and Romania

- The second cluster (marked in red): Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain

- The third cluster (marked in green): the Nordic countries, Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, and the Netherlands

- The fourth cluster (marked in blue): Ireland and Luxembourg.

4.4. Mean Values of Indicators

- Percentage of persons aged 65+ years at risk of poverty or social exclusion

- Income quintile share ratio S80/S20 for disposable income of people aged 65+ years

- Percentage of population aged 65+ years

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eurostat. Demography of Europe 2023 Interactive Edition. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/interactive-publications/demography-2023 (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Taguchi, H.; Latjin, M. The Effects of Demographic Dynamics on Economic Growth in EU Economies: A Panel Vector Autoregressive Approach. Popul. Ageing 2023, 16, 569–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Petalcorin, C.C.; Park, D.; Tian, S. Determinants of the Elderly Share of Population: A Cross-Country Empirical Analysis. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 165, 941–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, P.J.; Marshall, V.W.; Ryff, C.D.; Rosenthal, C.J. Well-being in Canadian seniors: Findings from the Canadian study of health and aging. Can. J. Aging/La Rev. Can. Du Vieil. 2000, 19, 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jivraj, S.; Nazroo, J.; Vanhoutte, B.; Chandola, T. Aging and subjective well-being in later life. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2014, 69, 930–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horley, J.; Lavery, J.J. Subjective well-being and age. Soc. Indic. Res. 1995, 34, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Social Exclusion and Subjective Well-being Among Older Adults in Europe: Findings from the European Social Survey. J. Gerontol. B 2021, 76, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Štreimikienė, D. Environmental indicators for the assessment of quality of life. Intelekt. Ekon. 2015, 9, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-J.; Kang, R.; Bai, X. A Meta-Analysis on the Influence of Age-Friendly Environments on Older Adults’ Physical and Mental Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanleerberghe, P.; De Witte, N.; Claes, C.; Schalock, R.L.; Verte, D. The quality of life of older people aging in place: A literature review. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 2899–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, Ö.; Çakıroğlu-Çevik, A. Quality of life in an ageing society. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 46, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A. Age and Attitudes; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Polverini, F.; Lamura, G. Italy: Quality of life in old age I. In Growing Older in Europe; Walker, A., Ed.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2005; pp. 55–82. [Google Scholar]

- Mollenkopf, H.; Kaspar, R.; Marcellini, F.; Ruoppila, I.; Szeman, Z.; Tacken, M.; Wahl, H.W. Quality of life in urban and rural areas of five European countries: Similarities and differences. Hallym Int. J. Aging 2004, 6, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanimir, A. Methods of a Multivariate Analysis of Non-Metric Data in Evaluating the Generational Perception of Social Characteristics. Folia Oecon. Stetin. 2020, 20, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanimir, A. The Perception of the Generational Assessment of Selected Social Behaviour—A Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Folia Oecon. Stetin. 2020, 20, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.; Lowenstein, A. European perspectives on quality of life in old age. Eur. J. Ageing 2009, 6, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A. A European perspective on quality of life in old age. Eur. J. Ageing 2005, 2, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahl, H.W.; Deeg, D.J.H.; Litwin, H. European ageing research in the social, behavioural and health areas: A multidimensional account. Eur. J. Ageing 2013, 10, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürges, H.; van Soest, A. Comparing the Well-Being of Older Europeans: Introduction. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 105, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özsoy, Ö.; Gürler, M. Poverty and social exclusion of older people in ageing European Union and Turkey. J. Public Health Berl. 2020, 30, 1969–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, K.; Garcia-Garzon, E.; Maguire, Á.; Matz, S.; Huppert, F.A. Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: A multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybysz, K.; Stanimir, A. How Active Are European Seniors—Their Personal Ways to Active Ageing? Is Seniors’ Activity in Line with the Expectations of the Active Ageing Strategy? Sustainability 2023, 15, 10404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramia, I.; Voicu, M. Life Satisfaction and Happiness among Older Europeans: The Role of Active Ageing. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 160, 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, L.A.; Cahalin, L.P.; Gerst, K.; Burr, J.A. Productive Activities and Subjective Well-Being among Older Adults: The Influence of Number of Activities and Time Commitment. Soc. Indic. Res. 2005, 73, 431–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozikaki, M.; Linardakis, M.; Micheli, K.; Philalithis, A. Activity Participation and Well-Being among European Adults Aged 65 years and Older. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 131, 769–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmayr, D.; Weichselbaumer, D.; Winter-Ebmer, R. Gender Differences in Active Ageing: Findings from a New Individual-Level Index for European Countries. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 151, 691–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somarriba Arechavala, N.; Zarzosa Espina, P. Quality of Life in the European Union: An Econometric Analysis from a Gender Perspective. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 142, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.N.; Pereira, L.N.; da Fé Brás, M.; Ilchuk, K. Quality of life under the COVID-19 quarantine. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 1389–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Diaz, L.; Durocher, E.; McAiney, C.; Richardson, J.; Letts, L. The Impact of a Canadian Model of Aging in Place on Community Dwelling Older Adults’ Experience of Physical Distancing during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ageing Int. 2023, 48, 872–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitman Schorr, A.; Yehuda, I.; Mor, R. The Protective Role of Group Activity Prior to COVID-19 Pandemic Quarantine on the Relation between Loneliness and Quality of Life during COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinesi, G.; Ciommi, M.; Gigliarano, C. Impact of COVID-19 on elderly population well-being: Evidence from European countries. Qual. Quant. 2023, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Grané, A.; Albarrán, I. A Global Indicator to Track Well-Being in the Silver and Golden Age. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 169, 1057–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhey, J.; Hess, S.; Boehnke, K.; Deutsch, F.; Eichhorn, J.; Kühnen, U.; Welzel, C. Life Satisfaction During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Human, Economic, Social, and Psychological Capital. J. Happiness Stud. 2023, 24, 2201–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socci, M.; Principi, A.; Di Rosa, M.; Quattrini, S.; Lucantoni, D. Motivations, Relationships, Health and Quality of Life of Older Volunteers in Times of COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, P.; Hendriksen, P.A.; Balikji, J.; Severeijns, N.R.; Sips, A.S.M.; Bruce, G.; Garssen, J.; Verster, J.C. COVID-19 Lockdown Effects on Mood: Impact of Sex, Age, and Underlying Disease. Psychiatry Int. 2023, 4, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettstein, M.; Wahl, H.W.; Schlomann, A. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Trajectories of Well-Being of Middle-Aged and older Adults: A Multidimensional and Multidirectional Perspective. J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 3577–3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantarero-Prieto, D.; Pascual-Sáez, M.; Blázquez-Fernández, C. What is Happening with Quality of Life Among the Oldest People in Southern European Countries? An Empirical Approach Based on the SHARE Data. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 140, 1195–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemieux, A. The University of the Third Age: Role of senior citizens. Educ. Gerontol. Int. Q. 1995, 21, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Hsu, W.C.; Chen, H.C. Age and gender’s interactive effects on learning satisfaction among senior university students. Educ. Gerontol. 2016, 42, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirdök, O.; Bölükbasi, A. The Role of Senior University Students’ Career Adaptability in Predicting Their Subjective Well-Being. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2018, 6, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, A. The impact of tourism and travel experience on senior travelers’ psychological well-being. J. Travel Res. 1998, 37, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J. A strategy for enhancing senior tourists’ well-being perception: Focusing on the experience economy. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sie, L.; Pegg, S.; Phelan, K.V. Senior tourists’ self-determined motivations, tour preferences, memorable experiences and subjective well-being: An integrative hierarchical model. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, I.; Balderas-Cejudo, A. Tourism towards healthy lives and well-being for older adults and senior citizens: Tourism agenda 2030. Tour. Rev. 2023, 78, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, V.W.Q. Meaningful Aging: A Relational Conceptualization, Intervention, and Its Impacts. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwano, S.; Kambara, K.; Aoki, S. Psychological Interventions for Well-Being in Healthy Older Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 2389–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, M.; Yu, N.X. Neighborhood Characteristics and Older Adults’ Well-Being: The Roles of Sense of Community and Personal Resilience. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 137, 949–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekäläinen, T.; Wilska, T.A.; Kokko, K. Leisure Consumption and well-Being among Older Adults: Does Age or Life Situation Matter? Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2017, 12, 671–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaksonen, S. A Research Note: Happiness by Age is More Complex than U-Shaped. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 19, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, B. The Best Years of Older Europeans’ Lives. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 160, 227–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojcieszek, A.; Kurowska, A.; Majda, A.; Kołodziej, K.; Liszka, H.; Gądek, A. Relationship between Optimism, Self-Efficacy and Quality of Life: A Cross-Sectional Study in Elderly People with Knee Osteoarthritis. Geriatrics 2023, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Curnutt, G. Sustaining Retirement during Lockdown: Annuitized Income and Older American’s Financial Well-Being before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salido, M.F.; Moreno-Castro, C.; Belletti, F.; Yghemonos, S.; Ferrer, J.G.; Casanova, G. Innovating European Long-Term Care Policies through the Socio-Economic Support of Families: A Lesson from Practices. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olejniczak, T. Innovativeness of Senior Consumers’ Attitudes—An Attempt to Conduct Segmentation. Folia Oecon. Stetin. 2021, 21, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olejniczak, M.; Olejniczak, T. The Fears of Elderly People in the Process of Purchasing Food Products. Folia Oecon. Stetin. 2020, 20, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesáková, D. Silver Consumers and Their Shopping Specifics. Oecon. Copernic. 2013, 4, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, H.; Snell, C.; Bouzarovski, S. Health, Well-Being and Energy Poverty in Europe: A Comparative Study of 32 European Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akdede, S.H.; Giovanis, E. The Impact of Migration Flows on Well-Being of Elderly Natives and Migrants: Evidence from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 160, 935–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soósová, M.S. Determinants of quality of life in the elderly. Cent. Eur. J. Nurs. Midw. 2016, 7, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, K.M.; Van Loon, M.S.; Van Nes, F.A.; Bosmans, J.E.; De Vet, H.C.; Ket, J.C.; Widdershoven, G.A.M.; Ostelo, R.W. What does quality of life mean to older adults? A thematic synthesis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Gil, M.; Mata García, A.; ElHichou-Ahmed, C. The Effect of Ageing, Gender an Environmental Problems in SubjectiveWell-Being. Land 2021, 10, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuberger, F.S.; Preisner, K. Parenthood and Quality of Life in Old Age: The Role of Individual Resources, the Welfare State and the Economy. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 138, 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steckermeier, L.C. The Value of Autonomy for the Good Life. An Empirical Investigation of Autonomy and Life Satisfaction in Europe. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 154, 693–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isengard, B.; König, R. Being Poor and Feeling Rich or Vice Versa? The Determinants of Unequal Income Positions in Old Age Across Europe. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 154, 767–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Walesiak, M.; Dudek, A. The Choice of Variable Normalization Method in Cluster Analysis. In Education Excellence and Innovation Management: A 2025 Vision to Sustain Economic Development during Global Challenges International Business Information Management Association; Soliman, K.S., Ed.; International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA): King of Prussia, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, T. ggforce: Accelerating ‘Ggplot2’. R Package Version 0.4.1. 2022. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggforce (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slowikowski, K. Ggrepel: Automatically Position Non-Overlapping Text Labels with ‘Ggplot2’. R Package Version 0.9.3. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggrepel (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Charrad, M.; Ghazzali, N.; Boiteau, V.; Niknafs, A. NbClust: An R Package for Determining the Relevant Number of Clusters in a Data Set. J. Stat. Softw. 2014, 61, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, J. Plotrix: A package in the red light district of R. R-News 2006, 6, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- South, A. rworldmap: A New R package for Mapping Global Data. R J. 2011, 3, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, T.; Cox, M. Multidimensional Scaling, 2nd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.; Cox, T. Multidimensional Scaling. In Handbook of Data Visualization. Springer Handbooks Comp. Statistics; Chen, C., Härdle, W., Unwin, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 315–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.L.; Yoon, K. Multiple Attribute Decision Making. Methods and Applications. In A State-of-the-Art Survey; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Małkowska, A.; Urbaniec, M.; Kosała, M. The impact of digital transformation on European countries: Insights from a comparative analysis. Equilibrium. Quart. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2021, 16, 325–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavrek, R.; Kovářová, E. Assessment of the social exclusion at the regional level using multi-criteria approach: Evidence from the Czech Republic. Equilibrium. Quart. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2021, 16, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodny, J.; Tutak, M. The level of implementing sustainable development goal “Industry, innovation and infrastructure” of Agenda 2030 in the European Union countries: Application of MCDM methods. Oecon. Copernic. 2023, 14, 47–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcerzak, A.P.; Pietrzak, M.B. Quality of Institutions for Knowledgebased Economy within New Institutional Economics Framework. Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis for European Countries in the Years 2000–2013. Econ. Sociol. 2016, 9, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellwig, Z. On the Optimal Choice of Predictors. In Towards a System of Human Capital Resources Indicators for Less Developed Countries; Gostkowski, A., Ed.; Papers Prepared for a UNESCO Research Project; Ossolineum, Polish Academy of Sciences Press: Wrocław, Poland, 1972; pp. 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Zavadskas, E.K.; Kaklauskas, A.; Šarka, V. The new method of multictiteria complex proportional assessment projects. In Technological and Economic Development of Economy; Zavadskas, E.K., Linnert, P., Eds.; Business Management; Technika: Vilnius, Lithuania, 1994; Volume 3, pp. 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen, J. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Berkeley, CA, USA, 21 June–18 July 1965; pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Małys, Ł. The approach to supply chain cooperation in the implementation of sustainable development initiatives and company’s economic performance. Equilibrium. Quart. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2023, 18, 255–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardelli, M.; Korzeb, Z.; Niedziółka, P. The banking sector as the absorber of the COVID-19 crisis? economic consequences: Perception of WSE investors. Oecon. Copernic. 2021, 12, 335–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konya, S. Panel Estimation of the Environmental Kuznets Curve for CO2 Emissions and Ecological Footprint: Environmental Sustainability in Developing Countries. Folia Oecon. Stetin. 2022, 22, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grané, A.; Albarrán, I.; Guo, Q. Visualizing Health and Well-Being Inequalities Among Older Europeans. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 155, 479–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybysz, K.; Stanimir, A. Measuring Activity—The Picture of Seniors in Poland and Other European Union Countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panek, T.; Zwierzchowski, J. Examining the Degree of Social Exclusion Risk of the Population Aged 50 + in the EU Countries Under the Capability Approach. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 163, 973–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogge, N.; Van Nijverseel, I. Quality of Life in the European Union: A Multidimensional Analysis. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 141, 765–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somarriba Arechavala, N.; Zarzosa Espina, P.; Pena Trapero, B. The Economic Crisis and its Effects on the Quality of Life in the European Union. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 120, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shucksmith, M.; Cameron, S.; Merridew, T.; Pichler, F. Urban–rural differences in quality of life across the European Union. Reg. Stud. 2009, 43, 1275–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorsi, G.; Manzi, F.; Del Riccio, M.; Setola, N.; Naldi, E.; Milani, C.; Giorgetti, D.; Dellisanti, C.; Lorini, C. Impact of the Built Environment and the Neighborhood in Promoting the Physical Activity and the Healthy Aging in Older People: An Umbrella Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirella, G.T.; Bąk, M.; Kozlak, A.; Pawłowska, B.; Borkowski, P. Transport innovations for elderly people. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2019, 30, 100381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogelj, V.; Bogataj, D. Social infrastructure of Silver Economy: Literature review and Research agenda. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 2680–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajewska, M.; Partyka, O.; Kwiatkowska, K.; Krysińska, M.; Bulira-Pawełczyk, J.; Czerw, A.I. Changes in the public health infrastructure in Poland in the context of an aging population. J. Educ. Health Sport 2018, 8, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Mea, V.; Popescu, M.H.; Gonano, D.; Petaros, T.; Emili, I.; Fattori, M.G. A communication infrastructure for the health and social care internet of things: Proof-of-concept study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2020, 8, e14583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2021–22, New York, UNDP. 2022. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2021-22 (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Walesiak, M.; Dehnel, G. Assessment of Changes in Population Ageing of Polish Provinces in 2002, 2010 and 2017 Using the Hybrid Approach. Econometrics 2019, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehnel, G.; Gołata, E.; Walesiak, M. Assessment of changes in population ageing in regions of the V4 countries with application of multidimensional scaling. Argum. Oecon. 2020, 44, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehnel, G.; Walesiak, M. A comparative analysis of economic efficiency of medium-sized manufacturing enterprises in districts of Wielkopolska province using the hybrid approach with metric and interval-valued data. Stat. Transit. New Ser. 2019, 20, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walesiak, M. Wizualizacja Wyników Porządkowania Liniowego Dla Danych Porządkowych Z Wykorzystaniem Skalowania Wielowymiarowego. Przegląd Stat. 2017, 64, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Symbol | Variable Description |

|---|---|

| Mean consumption expenditure for persons aged 60+ years (in Euro, in purchasing power standard per adult equivalent) | |

| Persons at risk of poverty or social exclusion aged 65+ years (percentage of the population aged 65+) | |

| Income quintile share ratio S80/S20 for disposable income of people aged 65+ years (ratio) | |

| Distribution of the population aged 65+ (percentage of the total population) | |

| Distribution of the population aged 65+ assessing their health status as good or very good (percentage of the population aged 65+) | |

| Housing cost overburden rate for the population aged 65+ (percentage of the population aged 65+) | |

| Annual old age pension (in Euro, in purchasing power standard per inhabitant) | |

| GDP at market prices (in Euro, in purchasing power standard per capita) | |

| Activity rate of persons aged 65+ (percentage of the population aged 65+) |

| Country | 2015 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 9 | 11 |

| Bulgaria | 27 | 27 |

| Czechia | 20 | 18 |

| Denmark | 11 | 10 |

| Germany | 17 | 8 |

| Estonia | 21 | 21 |

| Ireland | 2 | 2 |

| Greece | 26 | 26 |

| Spain | 10 | 13 |

| France | 5 | 7 |

| Croatia | 22 | 24 |

| Italy | 12 | 9 |

| Cyprus | 8 | 12 |

| Latvia | 23 | 23 |

| Lithuania | 24 | 22 |

| Luxembourg | 1 | 1 |

| Hungary | 19 | 19 |

| Malta | 13 | 14 |

| Netherlands | 4 | 3 |

| Austria | 3 | 4 |

| Poland | 18 | 20 |

| Portugal | 14 | 15 |

| Romania | 25 | 25 |

| Slovenia | 15 | 16 |

| Slovakia | 16 | 17 |

| Finland | 6 | 5 |

| Sweden | 7 | 6 |

| Cluster No. | x1 | x2 | x3 | x4 | x5 | x6 | x7 | x8 | x9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | |||||||||

| 1 | 7418.80 | 42.34 | 4.51 | 18.72 | 14.00 | 13.30 | 1091.27 | 17,690.12 | 7.76 |

| 2 | 13,472.27 | 18.55 | 3.76 | 17.18 | 24.55 | 6.13 | 1713.61 | 22,440.26 | 4.73 |

| 3 | 20,541.33 | 13.72 | 3.57 | 18.92 | 49.44 | 13.50 | 3216.88 | 32,132.02 | 5.68 |

| 4 | 28,423.00 | 12.10 | 3.79 | 13.30 | 55.85 | 3.10 | 2585.68 | 63,642.80 | 6.75 |

| 2020 | |||||||||

| 1 | 8679.60 | 43.80 | 4.61 | 20.10 | 19.70 | 8.86 | 1461.97 | 22,431.94 | 9.82 |

| 2 | 13,659.91 | 21.27 | 4.00 | 19.26 | 30.89 | 4.63 | 1983.76 | 24,873.35 | 5.67 |

| 3 | 21,351.22 | 15.88 | 3.53 | 20.10 | 52.83 | 11.08 | 3623.31 | 34,472.17 | 6.41 |

| 4 | 28,400.00 | 13.10 | 3.96 | 13.70 | 61.70 | 3.80 | 2954.03 | 70,063.60 | 7.75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bieszk-Stolorz, B.; Dmytrów, K. The Well-Being-Related Living Conditions of Elderly People in the European Union—Selected Aspects. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416823

Bieszk-Stolorz B, Dmytrów K. The Well-Being-Related Living Conditions of Elderly People in the European Union—Selected Aspects. Sustainability. 2023; 15(24):16823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416823

Chicago/Turabian StyleBieszk-Stolorz, Beata, and Krzysztof Dmytrów. 2023. "The Well-Being-Related Living Conditions of Elderly People in the European Union—Selected Aspects" Sustainability 15, no. 24: 16823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416823