The Association of Board Characteristics and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure Quality: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Brief Overview of Important CG–CSR Arrangements in Pakistan

3. Literature Review and Development of Board Characteristics and CSR Disclosure Quality Hypotheses

3.1. CG, CSR and CSR Disclosure Quality

3.2. Gender Diversity

3.3. Board Independence

3.4. Female Leadership

3.5. Board Size

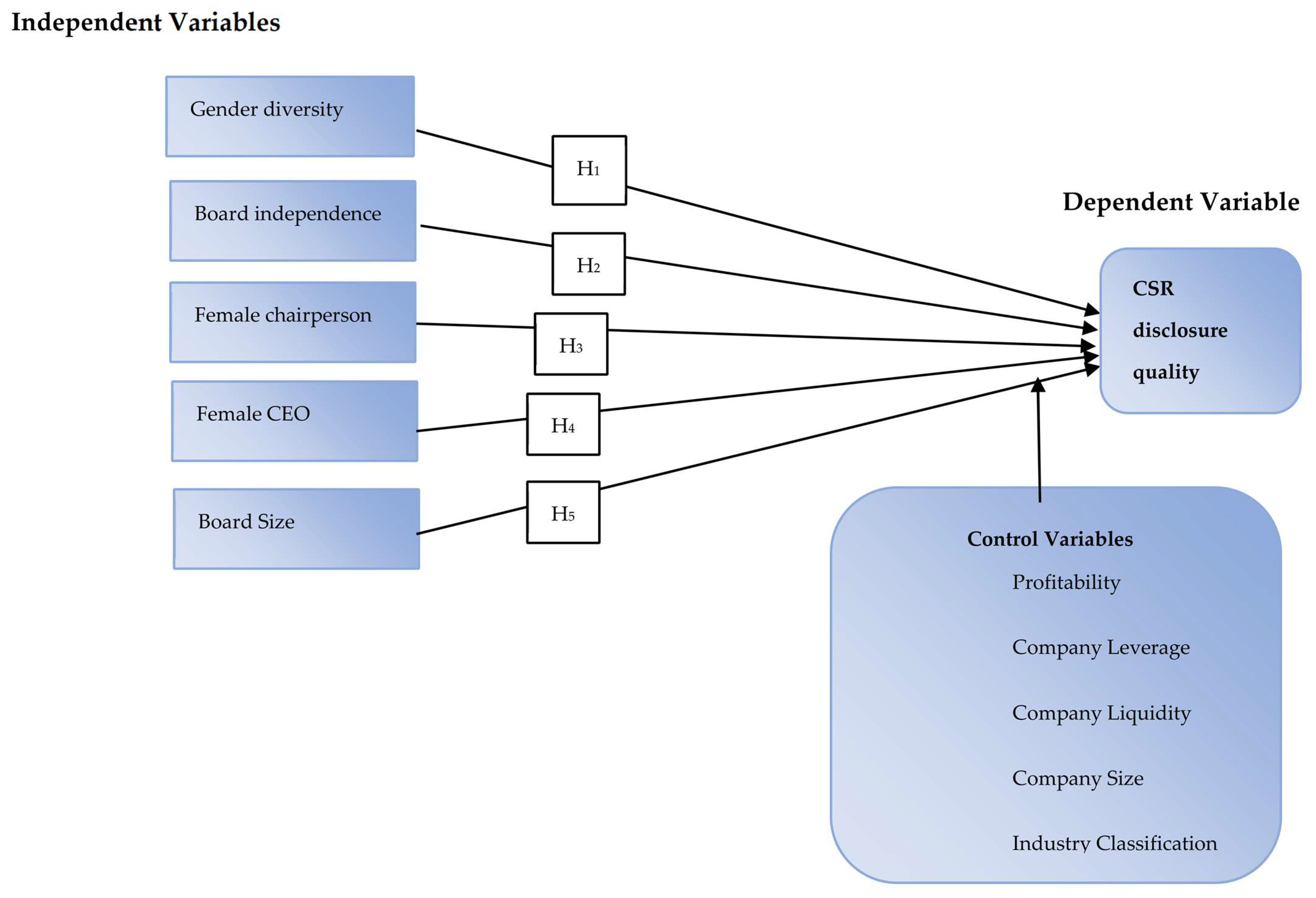

4. Empirical Research Design

4.1. Sample Size and Study Period

4.2. Variables and Measurements

4.2.1. Dependent Variable–CSR Disclosure Quality

4.2.2. Independent and Control Variables

5. Empirical Results and Discussions

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Univariate Analysis

5.3. Correlation Analysis

5.4. Multiple Regression Analysis

5.5. Robustness Check

6. Conclusions

7. Implications, Limitations, and Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ningtyas, C.E.; Sari, S.P. Board Diversity of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure in Infrastructure Companies Listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange. Int. J. Latest Res. Humanit. Soc. Sci. IJLRHSS 2023, 6, 325–330. [Google Scholar]

- Wirba, A.V. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): The Role of Government in promoting CSR. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives, A. Corporate Social Responsibility: The role of law and markets and the case of developing countries. Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 2008, 83, 199. [Google Scholar]

- Rob, G.; Reza, K.; Simon, L. Corporate social and environmental reporting. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1995, 8, 47–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmshurst, T.D.; Frost, G.R. Corporate environmental reporting: A test of legitimacy theory. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2000, 13, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, F.; Romero, S.; Ruiz, B. Women on boards: Do they affect sustainability reporting? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katmon, N.; Mohamad, Z.Z.; Norwani, N.M.; Farooque, O.A. Comprehensive Board Diversity and Quality of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: Evidence from an Emerging Market. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 447–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuente, J.; García-Sánchez, I.; Lozano, M. The role of the board of directors in the adoption of GRI guidelines for the disclosure of CSR information. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 737–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, L.S.; Saleh, N.M.; Ibrahim, I. Board diversity, company’s financial performance and corporate social responsibility information disclosure in Malaysia. Int. Bus. Educ. J. 2020, 13, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallin, C.; Michelon, G.; Raggi, D. Monitoring Intensity and Stakeholders’ Orientation: How Does Governance Affect Social and Environmental Disclosure? J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zattoni, A. Who Should Control a Corporation? Toward a Contingency Stakeholder Model for Allocating Ownership Rights. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 255–274. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41476024 (accessed on 15 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Riaz, Z.; Cullinan, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, F. Institutional Ownership and Value Relevance of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2311. [Google Scholar]

- Michelon, G.; Pilonato, S.; Ricceri, F. CSR reporting practices and the quality of disclosure: An empirical analysis. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2015, 33, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shan, Y.G.; Chang, M. Can CSR Disclosure Protect Firm Reputation During Financial Restatements? J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 173, 157–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che-Adam, N.; Lode, N.A.; Abd-Mutalib, H. The influence of board of directors ‘characteristics on the environmental disclosure among Malaysian companies. Malays. Manag. J. 2020, 23, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Yang, Z.; Shao, J.; Li, X. Board diversity and corporate social responsibility disclosure of multinational corporations. Appl. Econ. 2021, 53, 4884–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Luo, L.; Tang, Q. Gender diversity; board independence, environmental committee and greenhouse gas disclosure. Br. Account. Rev. 2015, 47, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geys, B.; Sørensen, R.J. The impact of women above the political glass ceiling: Evidence from a Norwegian executive gender quota reform. Elect. Stud. 2019, 60, 102050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Sector Companies CG Rules. 2017. Available online: https://ecgi.global/code/public-sector-companies-corporate-governance-rules-2013-revised (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Rao, K.; Carol, T. Board diversity and CSR reporting: An Australian study. Meditari Account. Res. 2016, 24, 182–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniak, R.; Hąbek, P. Quality Assessment of CSR Reports–Factor Analysis. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 220, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasser, Q.R.; Al Mamun, A.; Ahmed, I. Corporate Social Responsibility and Gender Diversity: Insights from Asia Pacific. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchiello, A.F.; Fellegara, A.M.; Kazemikhasragh, A.; Monferrà, S. Gender diversity on corporate boards: How Asian and African women contribute on sustainability reporting activity. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2021, 36, 801–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, H.M.; Waseem, R.; Khan, H.; Waseem, F.; Hasheem, M.J.; Shi, Y. Process Innovation as a Moderator Linking Sustainable Supply Chain Management with Sustainable Performance in the Manufacturing Sector of Pakistan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S. CSR in Pakistan: The case of the Khaadi controversy. In Corporate Responsibility and Digital Communities: An International Perspective towards Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 247–269. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, N. Corporate Social Responsibility and Development in Pakistan; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Scamardella, F. Law, globalisation, governance: Emerging alternative legal techniques. The Nike scandal in Pakistan. J. Leg. Plur. Unoff. Law 2015, 47, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umair, S.; Björklund, A.; Petersen, E.E. Social impact assessment of informal recycling of electronic ICT waste in Pakistan using UNEP SETAC guidelines. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 95, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WB. Country Climate and Development Report; WB: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fatima, M. A comparative study of CSR in Pakistan! Asian J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 6, 81–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Summary Report of Country-Wide Women’s Consultations; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- WEF. Global Gender Gap Report; WEF: Cologny, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Terjesen, S.; Couto, E.B.; Francisco, P.M. Does the presence of independent and female directors impact firm performance? A multi-country study of board diversity. J. Manag. Gov. 2016, 20, 447–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gull, A.A.; Abid, A.; Hussainey, K.; Ahsan, T.; Haque, A. Corporate governance reforms and risk disclosure quality: Evidence from an emerging economy. J. Account. Emerg. Econ. 2022, 13, 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, T.N.; Mortimer, T.; Bilal, M. Corporate Governance Codes in Pakistan: A. Review. J. Law Soc. Stud. JLSS 2020, 2, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Karaman, A.S.; Kilic, M.; Uyar, A. Board attributes; CSR engagement, and corporate performance: What is the nexus in the energy sector? Energy Policy 2020, 143, 111582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeed, S.A.; Lefen, L. An analysis of corporate social responsibility and firm performance with moderating effects of CEO power and ownership structure: A case study of the manufacturing sector of Pakistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassin, Y.; Van Rossem, A. Corporate governance in the debate on CSR and ethics: Sensemaking of social issues in management by authorities and CEOs. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2009, 17, 573–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A., II; Doh, J.P. The High Impact of Collaborative Social Initiatives; MIT Sloan Management Review: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, J.F.; Carvalho, A.O. Corporate governance in SMEs: A systematic literature review and future research. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, C.; Hussain, M.M.; Mohamed, E.K.; Basuony, M.A. Is corporate governance relevant to the quality of corporate social responsibility disclosure in large European companies? Int. J. Account. Inf. Manag. 2019, 27, 301–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananzeh, H. Corporate governance and the quality of CSR disclosure: Lessons from an emerging economy. Soc. Bus. Rev. 2022, 17, 280–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.R.; Simnett, R. CSR and assurance services: A research agenda. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2015, 34, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, A.; Lee, S.P.; Devi, S.S. The influence of governance structure and strategic corporate social responsibility toward sustainability reporting quality. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2014, 23, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ane, P. An Assessment of the Quality of Environmental Information Disclosure of Corporation in China. Syst. Eng. Procedia 2012, 5, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, G.; Parbonetti, A. The effect of corporate governance on sustainability disclosure. J. Manag. Gov. 2012, 16, 477–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvey, J.-N.; Giordano-Spring, S.; Cho, C.H.; Patten, D.M. The Normativity and Legitimacy of CSR Disclosure: Evidence from France. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 789–803. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24703458 (accessed on 14 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Hooks, J.; Van Staden, C.J. Evaluating environmental disclosures: The relationship between quality and extent measures. Br. Account. Rev. 2011, 43, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, A.; Bezemer, P.; Zattoni, A.; Huse, M.; Bosch, F.A.J.V.D.; Volberda, H.W. Boards of Directors’ Contribution to Strategy: A Literature Review and Research Agenda. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2009, 17, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, C.; Naiker, V.; Van Staden, C.J. The effect of board characteristics on firm environmental performance. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1636–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucheta-Martínez, M.C.; Gallego-Álvarez, I. An international approach of the relationship between board attributes and the disclosure of corporate social responsibility issues. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 612–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beji, R.; Yousfi, O.; Loukil, N.; Omri, A. Board Diversity and Corporate Social Responsibility: Empirical Evidence from France. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 173, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Khan, I.; Senturk, I. Board diversity and quality of CSR disclosure: Evidence from Pakistan. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2019, 19, 1187–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi, S.P.H.; Hien, T.T. Board and corporate social responsibility disclosure of multinational corporations. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2019, 27, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldamen, H.; Hollindale, J.; Ziegelmayer, J.L. Female audit committee members and their influence on audit fees. Account. Financ. 2018, 58, 57–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.; Tilt, C. Board Composition and Corporate Social Responsibility: The Role of Diversity, Gender, Strategy and Decision Making. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.; Tilt, C.; Laurence, L. Corporate governance and environmental reporting an Australian study. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2012, 12, 143–163. Available online: http://ejournals.ebsco.com/direct.asp?ArticleID=424A88204E8D4C1424E9 (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Hafsi, T.; Turgut, G. Boardroom Diversity and its Effect on Social Performance: Conceptualization and Empirical Evidence. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidro, H.; Sobral, M. The Effects of Women on Corporate Boards on Firm Value, Financial Performance, and Ethical and Social Compliance. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Lin, T.; Zhang, Y. Corporate Board and Corporate Social Responsibility Assurance: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. Are women greener? Corporate gender diversity and environmental violations. J. Corp. Financ. 2018, 52, 118–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekhili, M.; Nagati, H.; Chtioui, T.; Nekhili, A. Gender-diverse board and the relevance of voluntary CSR reporting. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2017, 50, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, A.; Qiu, Y.; Trojanowski, G. Board Attributes, Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy, and Corporate Environmental and Social Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shaer, H.; Zaman, M. Board gender diversity and sustainability reporting quality. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2016, 12, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barako, D.G.; Brown, A.M. Corporate social reporting and board representation: Evidence from the Kenyan banking sector. J. Manag. Gov. 2008, 12, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, S.; Rahman, N.; Post, C. The Impact of Board Diversity and Gender Composition on Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, K.; Imran, K.; Saeed, B.B. Does board diversity affect quality of corporate social responsibility disclosure? Evidence from Pakistan. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupley, K.H.; Brown, D.; Marshall, R.S. Governance, media and the quality of environmental disclosure. J. Account. Public Policy 2012, 31, 610–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Q.; Zhu, H.; Ding, H.-B. Board Composition and Corporate Social Responsibility: An Empirical Investigation in the Post Sarbanes-Oxley Era. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, R.; Piñero, R.; Redín, D.M. Understanding Independence: Board of Directors and CSR. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 552152. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koerniadi, H.; Tourani-Rad, A. Does board independence matter? Evidence from New Zealand. Australas. Account. Bus. Financ. J. 2012, 6, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, D.; Simkins, B.; Simpson, G. Corporate Governance, Board Diversity, and Firm Value. Financ. Rev. 2003, 38, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, L.L.; Mak, Y.T. Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure. J. Account. Public Policy 2003, 22, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamil, M.M.; Shaikh, J.M.; Ho, P.-L.; Krishnan, A. The influence of board characteristics on sustainability reporting. Asian Rev. Account. 2014, 22, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.A.; Angelidis, J.P. The corporate social responsiveness orientation of board members: Are there differences between inside and outside directors? J. Bus. Ethics 1995, 14, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, C.; Rahman, N.; Rubow, E. Green Governance: Boards of Directors’ Composition and Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility. Bus. Soc. 2011, 50, 189–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.-N.T. To be or not to be both CEO and Board Chair. Brook. L. Rev. 2010, 76, 65. [Google Scholar]

- Peni, E. CEO and Chairperson characteristics and firm performance. J. Manag. Gov. 2014, 18, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, F.; Kakabadse, A.; Kakabadse, N. The chairperson and CEO roles interaction and responses to strategic tensions. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2018, 18, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Pavelin, S. Gender and Ethnic Diversity Among UK Corporate Boards. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2007, 15, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.S.; Coombs, J.E. The Moderating Effects from Corporate Governance Characteristics on the Relationship between Available Slack and Community-Based Firm Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 107, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellwood, S.; Garcia-Lacalle, J. The Influence of Presence and Position of Women on the Boards of Directors: The Case of NHS Foundation Trusts. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, F.; Wang, F.; Naseem, M.A.; Ikram, A.; Ali, S. Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility Related to CEO Attributes: An Empirical Study. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244019899093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.; Ding, D.K.; Charoenwong, C. Investor reaction to women directors. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlotti, K.; Mazza, T.; Tibiletti, V.; Triani, S. Women in top positions on boards of directors: Gender policies disclosed in Italian sustainability reporting. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Akbar, A. Does increased representation of female executives improve corporate environmental investment? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntim, C.; Soobaroyen, T. Corporate Governance and Performance in Socially Responsible Corporations: New Empirical Insights from a Neo-Institutional Framework. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2013, 21, 468–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, R.; Zainuddin, Y.H.; Haron, H. The relationship between corporate social responsibility disclosure and corporate governance characteristics in Malaysian public listed companies. Soc. Responsib. J. 2009, 5, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtaruddin, M.; Rouf, M.A. Corporate Governance, Cultural Factors and Voluntary Disclosure: Evidence from Selected Companies in Bangladesh. Corp. Board Role Duties Compos. 2012, 8, 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazali, M. Ownership structure and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Some Malaysian evidence. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2007, 7, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttakin, M.B.; Khan, A.; Subramaniam, N. Firm characteristics, board diversity and corporate social responsibility. Pac. Account. Rev. 2015, 27, 353. Available online: https://login.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edb&AN=103634887&site=eds-live (accessed on 24 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Beattie, V.; Thomson, S. Lifting the lid on the use of content analysis to investigate intellectual capital disclosures. Account. Forum 2007, 31, 129–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, F. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Exploring Disclosure Quality in Australia and Pakistan: The Context of a Developed and Developing Country. Doctoral Dissertation, School of Business and Economics (TSBE), University of Tasmania, Tasmania, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Branco, M.C.; Rodrigues, L.L. Corporate Social Responsibility and Resource-Based Perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, W.; Frynas, J.G.; Mahmood, Z. Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Disclosure in Developed and Developing Countries: A Literature Review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, I.; Seele, P. The credibility of CSR (corporate social responsibility) reports in Europe. Evidence from a quantitative content analysis in 11 countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 122, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyahunzvi, D.K. CSR reporting among Zimbabwe’s hotel groups: A content analysis. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McGraw, P.; Katsouras, A. A review and analysis of csr practices in Australian second tier private sector firms. Employ. Relat. Rec. 2010, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gujarati, D.N. Basic Econometrics; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, N.B.J.; Rashid, A.; Gow, J. Board Independence and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Reporting in Malaysia. Australas. Account. Bus. Financ. J. 2017, 11, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, Z.; Alipour, M.; Faraji, O.; Ghanbari, M.; Jamshidinavid, B. Environmental disclosure quality and risk: The moderating effect of corporate governance. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2021, 12, 733–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.G.; Kim, R.S.; Aloe, A.M.; Becker, B.J. Extracting the variance inflation factor and other multicollinearity diagnostics from typical regression results. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 39, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.C.; Abeysekera, I.; Ma, S. Board diversity and corporate social disclosure: Evidence from Vietnam. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 833–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adib, M.; Xianzhi, Z.; Eiris, V. Board characteristics and Corporate Social Performance nexus—A multi-theoretical analysis-evidence from South Africa. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 21, 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Galbreath, J. The Impact of Board Structure on Corporate Social Responsibility: A Temporal View. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2016, 26, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, M.A.; Rehman, R.U.; Ikram, A.; Malik, F. Impact of board characteristics on corporate social responsibility disclosure. J. Appl. Bus. Res. (JABR) 2017, 33, 801–810. [Google Scholar]

- Handajani, L.; Subroto, B.; Sutrisno, T.; Saraswati, E. Does board diversity matter on corporate social disclosure? An Indonesian evidence. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 5, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, G.; Gray, S. Family ownership, board independence and voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Hong Kong. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2010, 19, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbash, M. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Soc. Responsib. J. 2016, 12, 740–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniffa, R.M.; Cooke, T.E. The impact of culture and governance on corporate social reporting. J. Account. Public Policy 2005, 24, 391–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Torea, N.; Fernandez-Feijoo, B.; de la Cuesta-González, M. The influence of ownership structure on the transparency of CSR reporting: Empirical evidence from Spain. Span. J. Financ. Account./Rev. Española De Financ. Y Contab. 2016, 46, 249–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarasen, S.D.D.; Je-Yen, T.; Rajangam, N. Board composition and corporate social responsibility in an emerging market. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2016, 16, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorelli, M.-F.; García-Sánchez, I.-M. Critical mass of female directors, human capital, and stakeholder engagement by corporate social reporting. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.M.; James, E.H. She’-e-os: Gender effects and investor reactions to the announcements of top executive appointments. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, G.N.; Butterfield, D.A. Exploring the influence of decision makers’ race and gender on actual promotions to top management. Pers. Psychol. 2002, 55, 397–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, M.; Lorsch, J.W. A Modest Proposal for Improved Corporate Governance. Bus. Lawyer 1992, 48, 59–77. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40687360 (accessed on 24 March 2023).

- Yekini, K.C.; Adelopo, I.; Andrikopoulos, P.; Yekini, S. Impact of board independence on the quality of community disclosures in annual reports. Account. Forum 2015, 39, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esa, E.; Ghazali, N.A.M. Corporate social responsibility and corporate governance in Malaysian government-linked companies. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2012, 12, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Y.-L.; Jiang, K.; Tan, W. ‘Doing-good’ and ‘doing-well’ in Chinese publicly listed firms. China Econ. Rev. 2012, 23, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jizi, M.; Salama, A.; Dixon, R.; Stratling, R. Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: Evidence from the US Banking Sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, E.; Ali, A.; Khan, I. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from Pakistan. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2016, 16, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, K.O.; Hussainey, K. Determinants of CSR disclosure quantity and quality: Evidence from non-financial listed firms in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2016, 13, 364–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barako, D.G.; Hancock, P.; Izan, I. Relationship between corporate governance attributes and voluntary disclosures in annual reports: The Kenyan experience. FRRaG Financ. Report. Regul. Gov. 2006, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Elzahar, H.; Hussainey, K. Determinants of narrative risk disclosures in UK interim reports. J. Risk Financ. 2012, 13, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Moataz, E.; Hussainey, K. Determinants of corporate governance disclosure in Saudi corporations. J. King Abdulaziz Univ. Econ. Adm. 2013, 27, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathuva, D. The Determinants of Forward-Looking Disclosures in Interim Reports for Non-Financial Firms: Evidence from a Developing Country. Int. J. Account. Financ. Report. 2015, 2, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S.; Ghosh, S. Corporate governance attributes, firm characteristics and the level of corporate disclosure: Evidence from the Indian listed firms. Decis. Sci. Lett. 2013, 2, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Pavelin, S. Factors influencing the quality of corporate environmental disclosure. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.; Rodrigues, L.L.; Craig, R. Corporate governance effects on social responsibility disclosures. Australas. Account. Bus. Financ. J. 2017, 11, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, M.; Abdullah, N.; Fatima, A. Determinants of environmental reporting quality in Malaysia. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Account. 2014, 22, 63–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, S.S.M.; Wong, K.S. A study of the relationship between corporate governance structures and the extent of voluntary disclosure7 7The helps given by the two anonymous reviewers and the Editors are gratefully acknowledged. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2001, 10, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamerschlag, R.; Möller, K.; Verbeeten, F. Determinants of voluntary CSR disclosure: Empirical evidence from Germany. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2011, 5, 233–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinidhi, B.; Gul, F.A.; Tsui, J. Female Directors and Earnings Quality*. Contemp. Account. Res. 2011, 28, 1610–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjoto, M.; Laksmana, I.; Lee, R. Board diversity and corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 641–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintoki, M.B.; Linck, J.S.; Netter, J.M. Endogeneity and the dynamics of internal corporate governance. J. Financ. Econ. 2012, 105, 581–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momin, M.A.; Parker, L.D. Motivations for corporate social responsibility reporting by MNC subsidiaries in an emerging country: The case of Bangladesh. Br. Account. Rev. 2013, 45, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Industry Group | Initial Sample | Final Sample |

|---|---|---|

| Consumer Discretionary | 9 | 8 |

| Consumer Staples | 3 | 3 |

| Energy | 8 | 7 |

| Financials | 31 | 30 |

| Healthcare | 2 | 2 |

| Industrials | 7 | 6 |

| Telecommunications and IT Services | 5 | 5 |

| Materials | 22 | 21 |

| Real Estate | 3 | 2 |

| Utilities | 10 | 10 |

| Total | 100 | 94 |

| Main Categories on the Disclosure Index | Sub-Categories | Max Possible Score on Each Main Category (Disclosure Levels = 4) × (Number of Sub-Categories) | Scoring Formulae of Sub-Category and Main Category of Disclosure Quality Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Relevance |

| 6 × 4 = 24 | Relevance index (RI) score = Actual Disclosure score obtained/24 |

| 2. Faithful Representation |

| 3 × 4 = 12 | Faithful Representation index (FI) score = Actual Disclosure score obtained/12 |

| 3. Understandability |

| 2 × 4 = 8 | Understandability index (UI) score = Actual Disclosure score obtained/8 |

| 4. Comparability |

| 2 × 4 = 8 | Comparability index (CI) score = Actual Disclosure score obtained/8 |

| 5. Timeliness |

| 1 × 4 = 4 | Timeliness index (TI) score = Actual Disclosure score obtained/4 |

| Total CSR Disclosure QUALITY Index (TCSRDQI) Score RI + FI + UI + CI + TI | |||

| Independent Variables | Symbol | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Gender Diversity | Gendrdiv | Proportion of female board of director members to total directors on the board |

| Board Independence | Independ | Proportion of independent and non- executive directors to total directors on the board |

| Female Chairperson | Femchair | 1 if the chairperson of the board is female, 0 otherwise |

| Female CEO | FemCEO | 1 if the CEO is female, 0 otherwise. |

| Board Size | Bsize | Total number of board members |

| Control Variables | ||

| Profitability: Return on Assets (ROA) | Prof | ROA = Earnings after tax/Total assets |

| Company Leverage: Financial Leverage | FrmLiq | Total debt/Total assets |

| Company Liquidity: Current Ratio | FrmLiq | Current assets/Current liabilities |

| Company Size | Comsize | Natural log of total assets at the end of the year |

| Industry Classification | IND | Dummy variables for the ten industry groups of Global Industry Classification scheme |

| Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR Disclosure Quality | 1.76 | 1.68 | 0.44 | 0.63 | 3.06 |

| Gender Diversity | 0.1 | 0 | 0.13 | 0 | 0.43 |

| Board Independence | 0.32 | 0.3 | 0.12 | 0 | 0.5 |

| Female Chairperson | 0.04 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | 1 |

| Female CEO | 0.02 | 0 | 0.11 | 0 | 1 |

| Board Size | 8.51 | 8 | 1.99 | 6.5 | 15.5 |

| Profit | 2.58 | 1.26 | 9.5 | −49.42 | 26.85 |

| Leverage | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0 | 1.78 |

| Liquidity | 1.38 | 1.07 | 1.48 | 0.09 | 10.24 |

| Company Size | 7.7 | 7.55 | 0.91 | 2.81 | 9.43 |

| (a) Univariate Analysis Results of Continuous Variables | |||||

| Low CSR Disclosure Quality (n = 51) | High CSR Disclosure Quality (n = 43) | Two Sample t-Test Statistics | |||

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean Difference |

| Gender Diversity | 0.1 | 0.13 | 0.1 | 0.12 | 0.001 |

| Board Independence | 0.33 | 0.12 | 0.31 | 0.11 | 0.026 |

| Board Size | 8.28 | 2.07 | 8.77 | 1.89 | −0.483 |

| Profit | 0.29 | 11.59 | 5.29 | 5.09 | −4.990 *** |

| Leverage | 0.28 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.2 | 0.067 |

| Liquidity | 1.58 | 1.72 | 1.15 | 1.13 | 0.4223 * |

| Company Size | 7.47 | 0.72 | 7.96 | 1.05 | −0.489 *** |

| (b) Univariate Analysis Results of Dichotomous Variables | |||||

| Low CSR Disclosure Quality (n = 51) | High CSR Disclosure Quality (n = 43) | Pearson Chi-Square | |||

| Variable | Without | With | Without | With | Mean Difference |

| Female Chairperson | 47 | 4 | 43 | 0 | 2.859 |

| Female CEO | 49 | 2 | 43 | 0 | 1.723 |

| CSR Disclosure Quality | Gender Diversity | Board Independence | Female Chairperson | Female CEO | Board Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR Disclosure Quality | 1 | |||||

| Gender Diversity | 0.031 (0.775) | 1 | ||||

| Board Independence | −0.190 (0.066) | 0.063 (0.547) | 1 | |||

| Female Chairperson | −0.175 (0.091) | 0.415 ** (0.00) | −0.055 (0.595) | 1 | ||

| Female CEO | −0.142 (0.171) | 0.143 (0.169) | 0.065 (0.536) | −0.029 (0.778) | 1 | |

| Board Size | 0.202 (0.051) | −0.033 (0.749) | −0.308 ** (0.003) | −0.147 (0.158) | −0.118 (0.258) | 1 |

| Tolerance | VIF | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender Diversity | 0.739 | 1.353 |

| Board Independence | 0.803 | 1.245 |

| Female Chairperson | 0.866 | 1.155 |

| Female CEO | 0.951 | 1.052 |

| Board Size | 0.803 | 1.246 |

| Panel 1: OLS Regression | Panel 2: 2SLS Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficients | p-Value | Coefficients | p-Value |

| Independent variables | ||||

| Gender Diversity | 0.443 | 0.200 | 0.456 | 0.175 |

| Board Independence | −0.395 | 0.256 | −0.844 | 0.626 |

| Female Chairperson | −0.424 *** | 0.009 | −0.431 ** | 0.037 |

| Female CEO | −0.611 *** | 0.008 | −0.341 *** | 0.299 |

| Board Size | 0.020 | 0.446 | 0.012 | 0.739 |

| Control variables | ||||

| Profit | 0.015 ** | 0.020 | 0.012 *** | 0.001 |

| Leverage | −0.230 | 0.113 | −0.261 * | 0.078 |

| Liquidity | −0.013 | 0.625 | −0.009 | 0.784 |

| Company Size | 0.125 ** | 0.056 | 0.114 ** | 0.042 |

| Industry | ||||

| Consumer Staples | −0.382 | 0.259 | −0.237 | 0.382 |

| Consumer Discretionary | −0.323 * | 0.082 | −0.476 * | 0.073 |

| Energy | −0.091 | 0.728 | −0.407 | 0.167 |

| Financials | −0.520 *** | 0.003 | −0.342 ** | 0.006 |

| Healthcare | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.00 |

| Industrials | −0.170 | 0.392 | −0.159 | 0.244 |

| Materials | −0.244 | 0.165 | −0.173 | 0.148 |

| Real Estate | −0.456 ** | 0.037 | −0.307 *** | 0.180 |

| Telecommunication and IT | −0.525 *** | 0.012 | −0.731 ** | 0.061 |

| Utilities | −0.429 ** | 0.037 | −0.245 ** | 0.046 |

| Constant | 1.141 | 0.908 | ||

| R square | 0.47 | 0.447 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hameed, F.; Alfaraj, M.; Hameed, K. The Association of Board Characteristics and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure Quality: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16849. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416849

Hameed F, Alfaraj M, Hameed K. The Association of Board Characteristics and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure Quality: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability. 2023; 15(24):16849. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416849

Chicago/Turabian StyleHameed, Faisal, Mohammad Alfaraj, and Khizar Hameed. 2023. "The Association of Board Characteristics and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure Quality: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan" Sustainability 15, no. 24: 16849. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416849

APA StyleHameed, F., Alfaraj, M., & Hameed, K. (2023). The Association of Board Characteristics and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure Quality: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability, 15(24), 16849. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416849