Electrification of Last-Mile Delivery: A Fleet Management Approach with a Sustainability Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- A comprehensive optimization approach by integrating MOLP and Greenhouse Gas Protocol standards for corporate emissions accounting and reporting;

- Optimization of the fleet mix and minimizing cost and emissions accounted for in the corporate sustainability report throughout the entire service life of the vehicle in the fleet;

- Assessing cost and emissions issues simultaneously for different types of electric powertrains for LCVs, considering their on-site refueling infrastructure means;

- Assessment of the energy supply pathway used. The electricity mix and the use of hydrogen purchased or on-site produced by electrolysis have been taken into account. In the case of purchased hydrogen, it is explored the use of blended green hydrogen with 40% of hydrogen obtained via steam methane reforming (SMR);

- Highlighting the weight of scope 3 emissions in the corporate sustainability report for last-mile transport activities using electrified vehicles in the fleet.

2. The Literature Background

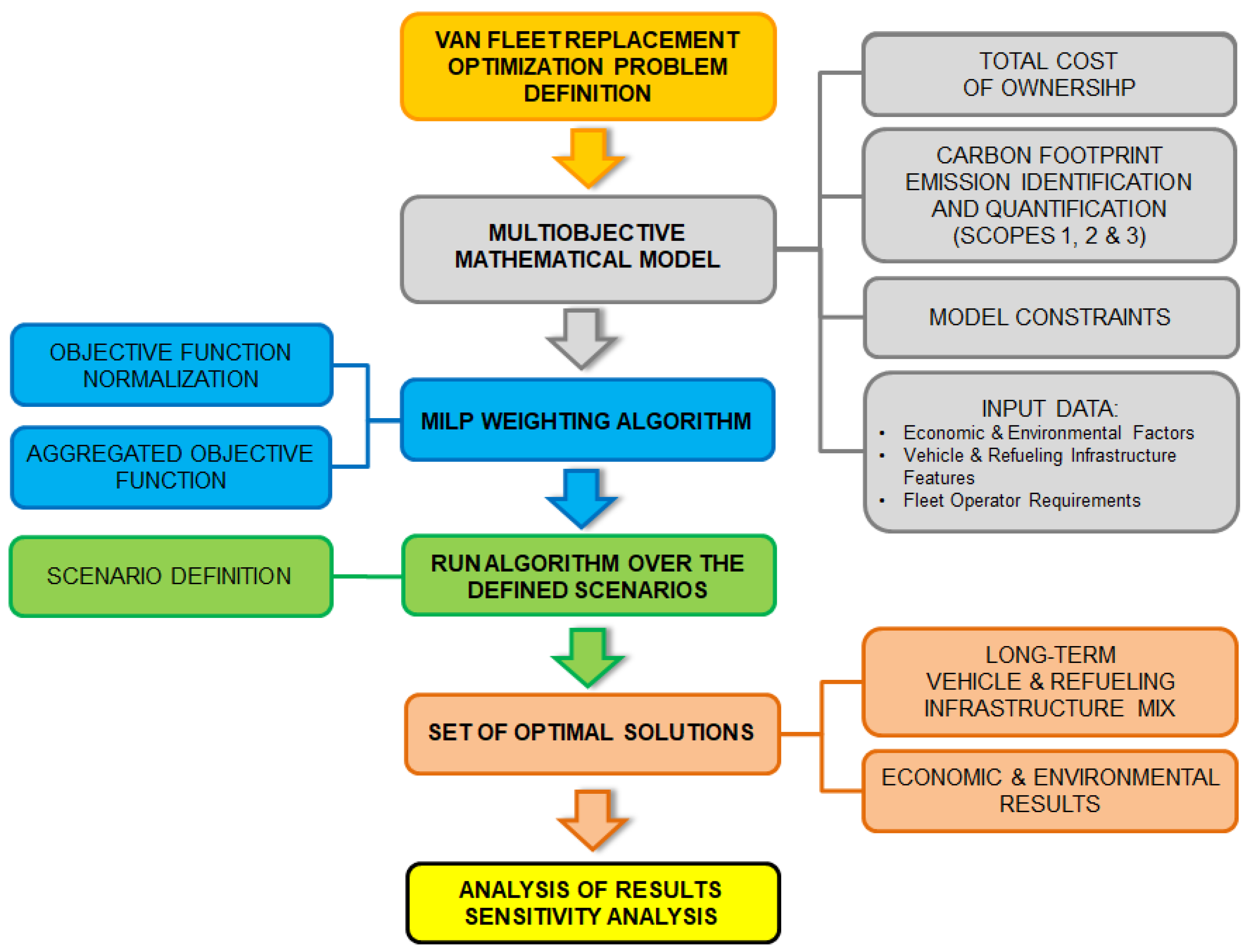

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Model Definition and Mathematical Formulation

3.1.1. Total cost of ownership calculation

3.1.2. Evaluation of Corporate Carbon Footprint

Direct Emissions: Scope 1

Indirect Emissions: Scope 2

- BEV: the electricity power consumption comes from recharging the battery;

- FCEREV: the electric power consumption is derived from both battery and hydrogen supply;

- FCEV: the electricity is used for hydrogen supply.

Other Indirect Emissions: Scope 3

3.2. Definition of Scenarios

3.3. Model Data

- The planning horizon time frame is 25 years (2025 to 2050);

- At the beginning of the planning horizon, the fleet company has a specific quantity of CNG vans evenly distributed across various ages, spanning from 0 to the duration of the ownership period, and there are no energy supply infrastructures for electric vans;

- The budgetary limit for acquiring vehicles and infrastructure assets is high enough to facilitate the replacement of older vans with the highest-cost electric van.

4. Results and Discussion

- Fleet mix: distribution of fleet vehicles (type and age) every year within the planning horizon and the evolution of the infrastructure required to service the van fleet. These results are post-processed and translated into the fleet share and the replacement rate parameters. The fleet share shows the average share of each type of electric van in the fleet, and the replacement rate expresses the percentage of time when the electric vans in the fleet are the majority (over 90%);

- Economic results: average cost per kilometer of the fleet and cost breakdown;

- Environmental results: average emissions per kilometer of the fleet and emissions broken down into scopes 1, 2, and 3.

4.1. Fleet Mix

4.2. Economic and Environmental Results

- The consideration of scope 3 in the emissions report increases the level of accounted emissions average of over 71% in H2P and H2G scenarios;

- The emissions reported in scope 3 have approximately the same weight as the sum of the emissions accounted for in scopes 1 and 2, except for the S4 scenarios with the longest ownership period. Additionally, when emissions in scope 3 are considered, the emission level in scope 1 grows. This is a result of the increased presence of CNG vans in the fleet mix;

- The emissions reported in scope 2 are always higher in H2G scenarios than in the H2P. The major and minor differences are shown in the S2 and S1 scenarios, with the largest and lowest annual mileages, respectively. However, the emissions in scope 3 are higher in H2P scenarios except for the scenario with the higher annual mileage (S2). These results highlight the importance of the electricity production mix and the hydrogen distribution in scenarios with high distances traveled per year;

- Concerning van selection, the consideration of scope 3 emissions has a low effect in H2P scenarios with FCEREV and FCEV vans in the fleet mix. Nevertheless, accounting for scope 3 emissions in H2G scenarios changes the preferred van option from BEV to FC-EREV, except for the longest annual mileage (S2-G).

4.3. Sensitivity and Solution Robustness Analysis

- Cost and emissions per kilometer decrease when annual mileage increases. This is consistent with the increment of the EV replacement rate and the drop-off in the ownership period;

- Despite higher discount rates penalizing EV vans, cost and emissions per kilometer decrease. On this matter, the values considered for the discount rate are not high enough to significantly reduce the EV replacement rate. In addition, when the inflation index increases, costs and emissions grow;

- Electricity EF has a significant effect on emissions and, to a lesser extent, on the EV replacement rate;

- Higher emissions are associated with higher costs per kilometer.

4.4. Research Findings Summary

- The results obtained for the optimal solution (BAL) in the scenarios analyzed show that the most significant model parameters are the electricity EF, the yearly mileage, and the van’s ownership period, followed by the purchase price of fuel-cell-powered vans and the discount rate and inflation, whereas the fuel-cell-powered van maintenance cost and the electricity price show a lower effect. Concerning related hydrogen parameters, only H2P scenarios are affected. Hydrogen price is highly influenced in scenarios with higher yearly mileage, over 30.000 km. Nevertheless, the EF of blended hydrogen has a low effect;

- The FCEREV vans achieve the right balance between emissions and the economy of use in a wide range of H2P and H2G scenarios. This type of van is suitable for moderate annual distances (up to 30.000 km) when scope 3 emissions are accounted for. Nevertheless, if scope 3 emissions are out of scope, then the optimal distance is reduced to 20.000 km. Meanwhile, the BEV vans are optimal for the H2G scenario for larger annual distances when scope 3 emissions are reported (over 40.000 km). Additionally, it should be noted that FCEV represents an optimal option in the H2P scenario with high annual mileage (over 40.000 km). However, if scope 3 emissions are not accounted for, BEVs are optimal for moderate distances (over 30.000 km). Thus, regardless of the higher purchase costs, EV vans are the best option with high utilization levels. These results are consistent with conclusions drawn in prior research works [14,23,62], but the breakeven distance is higher when scope 3 emissions are considered;

- The average fleet emissions per kilometer are determined by yearly mileage, the van’s ownership period, the electricity production mix, and the hydrogen pathway. The emissions are higher in the H2G scenarios except for the scenarios with the lowest annual mileage (under 20.000 km). On average, the difference is 20.7% if the emissions scopes reported are 1 and 2 and 16% when the emissions in scope 3 are accounted for. Therefore, from the emissions inventorying point of view, the purchased hydrogen scenario (H2P) is the most favorable, and it is not efficient to use grid electricity to produce hydrogen by on-site electrolysis. As previous investigations’ outcomes show [14,23,58], the emissions from energy pathway production and distribution have important environmental implications, but they are more significant if scope 3 emissions are reported;

- The consideration of scope 3 in the emissions report increases the level of accounted emissions by an average of over 71%. The emissions reported in scope 3 have approximately the same weight as the sum of the emissions accounted for in scopes 1 and 2, except for the S4 scenarios with the longest ownership period. Additionally, when scope 3 emissions are taken into account, the EV replacement rate is lower, and the fleet mix is affected. This aspect is especially noteworthy in H2G scenarios because of changes in the preferred van options from BEV to FC-EREV, except for the longest annual mileage (S2-G). These results point out the importance of the emissions generated during EV van manufacturing;

- The average cost per kilometer is similar in the H2G and H2P scenarios, considering an average price for hydrogen and electricity of EUR 4.2/kg and EUR 168/MWh, but it is obtained with different van powertrains, BEV in the H2G scenarios and FCEREV in the H2P scenarios. With moderate annual mileage (below 30.000 km), long ownership periods (over 8 years), and a large number of vehicles in the fleet (over 200 vehicles), the FCEREV van is the best option with reductions in costs and emission levels to 2.7% and 18.5%, respectively, compared to BEV. Nevertheless, higher annual mileage (over 40.000 km) gives an advantage to the BEV vans with a cost reduction of 21.4% but with an emission increment of 41.4%. Furthermore, longer ownership periods (10 years) allow for reaching lower operating costs per kilometer. Additionally, the small fleet vans with fuel cell vans are more economically affected by the hydrogen supply infrastructure cost. Additionally, the smaller fleets with fuel cell vans are economically affected by the hydrogen supply infrastructure cost;

- There is an emission–cost correlation, and there is a cost increase for reducing fleet emissions. This tendency is also observed in other previous studies [23,35,59]. However, the life cycle emissions structure is different for EV and CNG vans; while operation emissions are high for CNG vans compared to production emissions values, in EVs, it is quite the opposite [50,54]. This trend is observed in the distribution of emissions in scopes 2 and 3.

5. Conclusions

- The uptake of electric vans for last-mile delivery activity is strongly dependent on the energy emission factor. The reduction in electricity mix EF (under 0.1 kgCO2e/kWh) enables several types of electric powertrains to participate in the fleet mix. On the other hand, the EF of blended hydrogen has a low effect. In this sense, the use of this type of hydrogen for transportation can accelerate the penetration of fuel-cell commercial vehicles in the market;

- Energy price has a strong influence on the competitiveness of electric vans in scenarios with higher yearly mileages (over 30.000 km). In the case of electricity, the price should be under EUR 0.17/kWh. Meanwhile, the hydrogen cost should be under EUR 4.6/kg;

- The FCEREV vans achieve the right balance between emissions and the economy of use in a wide range of scenarios. This type of van is suitable for moderate annual distances (up to 30.000 km) when scope 3 emissions are accounted for. Nevertheless, if scope 3 emissions are out of scope, then the optimal distance is reduced to 20.000 km. Additionally, it should be noted that FCEV is an optimal option in the H2P scenario with high annual mileage (over 40.000 km);

- The BEV vans are optimal in H2G scenarios for larger annual distances (over 40.000 km). However, if scope 3 emissions are not accounted for, BEVs are optimal for moderate distances (over 30.000 km);

- The emissions are higher in the H2G scenarios except for the scenarios with the lowest annual mileage (under 20.000 km). Therefore, from the emissions inventorying point of view, the purchased hydrogen scenario (H2P) is the most favorable, and it is not efficient to use grid electricity to produce hydrogen by on-site electrolysis with the actual electricity mix EF (0.25 kgCO2e/kWh);

- In the accounting of scope 3 emissions in the corporate report, the fleet mix is affected, and the EV replacement rate is lower. This aspect is especially noteworthy for BEV vans in scenarios with moderate annual mileage (under 40.000 km);

- The consideration of scope 3 emissions raises the importance of the emissions generated during EV van manufacturing and energy production and distribution pathway. In this sense, the organization has a better understanding of the full GHG impact of their operations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| L | Compressed natural gas | LCA | Life cycle assessment |

| EF | Emission factor | LCC | Life cycle cost |

| EV | Electric Vehicle | LCV | Light commercial vehicle |

| GLF | Grid loss factor | MILP | Mixed Integer Linear Programming |

| BEV | Battery electric vehicle | MOLP | Multi-Objective Linear Programming |

| FCEV | Fuel cell electric vehicle | M&R | Maintaining and repairing |

| FCEREV | Fuel cell extended range electric vehicle | PHEV | Plug-in hybrid electric vehicle |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas | PV | Passenger vehicle |

| HEV | Hybrid electric vehicle | SMR | Steam Methane Reforming |

| HRS | Hydrogen refueling station | TDCO | Total Discounted Cost of Ownership |

| ICE | Internal combustion engine |

References

- European Environment Agency. EEA Transport and Environment Report 2022. Digitalisation in the Mobility System: Challenges and Opportunities; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UNFCCC. National Inventory Submissions. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/transparency-and-reporting/reporting-and-review-under-the-convention/national-inventory-submissions-2022 (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- European Commission. The EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets_en (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Schroten, A.; Julius, K.; Scholten, P. Research for TRAN Committee—Pricing Instruments on Transport Emissions; European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. White Paper: Roadmap to a Single European Transport Area—Towards a Competitive and Resource Efficient Transport System; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aditjandra, P.T.; Galatioto, F.; Bell, M.C.; Zunder, T.H. Evaluating the Impacts of Urban Freight Traffic: Application of Micro-Simulation at a Large Establishment. Eur. J. Transp. Infrastruct. Res. 2016, 16, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asociación de Fabricantes y Distribuidores (AECOC). Los Impactos Nocivos del Transporte Urbano en España. Available online: https://www.aecoc.es/noticias/los-impactos-nocivos-del-transporte-urbano-en-espana-suponen-un-coste-economico-del-2-sobre-el-pib/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Lean & Green.Lean and Green Program. Available online: https://www.lean-green.eu/program_co2_action_plan/ (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- The Last-Mile Delivery Challenge; Capgemini Research Institute: Paris, France, 2019.

- Seroka-Stolka, O. The Development of Green Logistics for Implementation Sustainable Development Strategy in Companies. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 151, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, P.; Colicchia, C.; Creazza, A. Is Environmental Sustainability a Strategic Priority for Logistics Service Providers? J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 198, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Foggia, G. Drivers and Challenges of Electric Vehicles Integration in Corporate Fleet: An Empirical Survey. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2021, 41, 100627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albitar, K.; Al-Shaer, H.; Liu, Y.S. Corporate Commitment to Climate Change: The Effect of Eco-Innovation and Climate Governance. Res. Policy 2023, 52, 104697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alp, O.; Tan, T.; Udenio, M. Transitioning to Sustainable Freight Transportation by Integrating Fleet Replacement and Charging Infrastructure Decisions. Omega 2022, 109, 102595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanco, M.; Cat, L.; Garat, S. A Break-Even Analysis for Battery Electric Trucks in Latin America. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 1354–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mierlo, J.; Messagie, M.; Rangaraju, S. Comparative Environmental Assessment of Alternative Fueled Vehicles Using a Life Cycle Assessment. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 25, 3439–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicer, Y.; Dincer, I. Life Cycle Environmental Impact Assessments and Comparisons of Alternative Fuels for Clean Vehicles. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 132, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pero, F.; Delogu, M.; Pierini, M. Life Cycle Assessment in the Automotive Sector: A Comparative Case Study of Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) and Electric Car. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2018, 12, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmiroli, B.; Venditti, M.; Dotelli, G.; Spessa, E. The Transport of Goods in the Urban Environment: A Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Electric, Compressed Natural Gas and Diesel Light-Duty Vehicles. Appl. Energy 2020, 260, 114236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onat, N.C.; Abdella, G.M.; Kucukvar, M.; Kutty, A.A.; Al-Nuaimi, M.; Kumbaroğlu, G.; Bulu, M. How Eco-Efficient Are Electric Vehicles across Europe? A Regionalized Life Cycle Assessment-Based Eco-Efficiency Analysis. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 941–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorrano, M.; Danielis, R.; Giansoldati, M. Electric Light Commercial Vehicles for a Cleaner Urban Goods Distribution. Are They Cost Competitive? Res. Transp. Econ. 2021, 85, 101022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Figliozzi, M. An Economic and Technological Analysis of the Key Factors Affecting the Competitiveness of Electric Commercial Vehicles: A Case Study from the USA Market. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2013, 26, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ercan, T.; Tatari, O. Life Cycle Based Multi-Criteria Optimization for Optimal Allocation of Commercial Delivery Truck Fleet in the United States. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2016, 8, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-dal’ain, R.; Celebi, D. Planning a Mixed Fleet of Electric and Conventional Vehicles for Urban Freight with Routing and Replacement Considerations. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 73, 103105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, A.S.; Kilic, M.; Uyar, A. Green Logistics Performance and Sustainability Reporting Practices of the Logistics Sector: The Moderating Effect of Corporate Governance. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Martínez, E.; Marín-Hernández, S.; Santos-Jaén, J.-M. Sustainability, Corporate Social Responsibility, Non-Financial Reporting and Company Performance: Relationships and Mediating Effects in Spanish Small and Medium Sized Enterprises. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 35, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffer, M.; Klein, P.S.; Laporte, G.; Walther, G. Integrated Planning for Electric Commercial Vehicle Fleets: A Case Study for Retail Mid-Haul Logistics Networks. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 291, 944–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GreenHouse Gas Protocol. GHG Protocol—Calculation Tools. Available online: https://ghgprotocol.org/calculation-tools (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Redmer, A. Strategic Vehicle Fleet Management–A Joint Solution of Make-or-Buy, Composition and Replacement Problems. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 2020, 28, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Thomas, V.M.; Brown, M.A. Electric Urban Delivery Trucks: Energy Use, Greenhouse Gas Emissions, and Cost-Effectiveness. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 8022–8030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, A.; Fischbeck, P.; Matthews, H.S. Environmental and Economic Comparison of Diesel and Battery Electric Delivery Vans to Inform City Logistics Fleet Replacement Strategies. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 64, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, A.; Renaldy, T.; Breuning, L.; Hamacher, T.; You, F. Electrifying Light Commercial Vehicles for Last-Mile Deliveries: Environmental and Economic Perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 416, 137933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figliozzi, M.A.; Boudart, J.A.; Feng, W. Economic and Environmental Optimization of Vehicle Fleets. Transp. Res. Rec. 2011, 2252, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Figliozzi, M. Vehicle Technologies and Bus Fleet Replacement Optimization: Problem Properties and Sensitivity Analysis Utilizing Real-World Data. Public Transp. 2014, 6, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemme, R.F.F.; Arruda, E.F.; Bahiense, L. Optimization Model to Assess Electric Vehicles as an Alternative for Fleet Composition in Station-Based Car Sharing Systems. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 67, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Lownes, N. When to Go Electric? A Parallel Bus Fleet Replacement Study. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 72, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006; ISO Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; Volume 3, p. 32.

- Marler, R.T.; Arora, J.S. Survey of Multi-Objective Optimization Methods for Engineering. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2004, 26, 369–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriari, M.; Ehsanifar, M.; Rokhsati, A. Selecting the Most Preferable Weights in Multi Objective Programming. Am. J. Sci. Res. 2011, 28, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Schmied, M.; Knörr, W.; Friedl, C.; Hepburn, L. Calculating GHG Emissions for Freight Forwarding and Logistics Services; European Association for Forwarding, Transport, Logistics and Customs Services (CLECAT): Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wulf, C.; Kaltschmitt, M. Hydrogen Supply Chains for Mobility-Environmental and Economic Assessment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bareiß, K.; de la Rua, C.; Möckl, M.; Hamacher, T. Life Cycle Assessment of Hydrogen from Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolysis in Future Energy Systems. Appl. Energy 2019, 237, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E4tech H2 Emission Potential Literature Review; Department for Business Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS): London, UK. 2019. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5cc6f1e640f0b676825093fb/H2_Emission_Potential_Report_BEIS_E4tech.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Industria y Energía. Factores de Emisión de CO2 y Coeficientes de Paso a Energía Primaria de Diferentes Fuentes de Energía Final En El Sector de Edificios En España; Ministerio de Industria, Energía y Turismo: Madrid, España, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- IEA Emission Factors 2020—Data Base Documentation. 2020. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/24422203-de22-4fe6-8d54-f51911addb8b/CO2KWH_Methodology.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- DOE. Hydrogen Delivery. Fuel Cell Technologies; Office Multi-Year Research, Development and Demonstration Plan. 2015. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2015/08/f25/fcto_myrdd_delivery.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Ligen, Y.; Vrubel, H.; Girault, H.H. Mobility from Renewable Electricity: Infrastructure Comparison for Battery and Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2018, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsden, T.; Ruth, M.; Diakov, V. Hydrogen Pathways: Cost, Well-to-Wheels Energy Use, and Emissions for the Current Technology Status of 10 Hydrogen Production, Delivery, and Distribution Scenarios; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Denver, CO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Buberger, J.; Kersten, A.; Kuder, M.; Eckerle, R.; Weyh, T.; Thiringer, T. Total CO2-Equivalent Life-Cycle Emissions from Commercially Available Passenger Cars. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo Campo, O.; Álvarez Fernández, R. Economic Optimization Analysis of Different Electric Powertrain Technologies for Vans Applied to Last Mile Delivery Fleets. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Estado de Medio Ambiente. Emisiones de Gases de Efecto Invernadero, 1999–2020; Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico (MITECO): Madrid, España, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Red Electrica de España (REE). La Eólica se Convierte en la Principal Fuente de Generación de Energía Eléctrica en España en 2021. Available online: https://www.ree.es/es/sala-de-prensa (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Simons, S.; Azimov, U. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Propulsion Systems for Heavy-Duty Transport Applications. Energies 2021, 14, 3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieker, G. A Global Comparison of the Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Combustin Engine and Electric Passenger Cars; The International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT): Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yeow, L.W.; Yan, Y.; Cheah, L. Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Alternative Fuels and Powertrains for Medium-Duty Trucks: A Singapore Case Study. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 105, 103258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Q.; Zhao, F.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, S.; Hao, H. Comparative Study on Life Cycle CO2 Emissions from the Production of Electric and Conventional Vehicles in China. Energy Procedia 2017, 105, 3584–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, C.; Hofer, J.; Althaus, H.J.; Del Duce, A.; Simons, A. The Environmental Performance of Current and Future Passenger Vehicles: Life Cycle Assessment Based on a Novel Scenario Analysis Framework. Appl. Energy 2015, 157, 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desantes, J.M.; Novella, R.; Pla, B.; Lopez-Juarez, M. Impact of Fuel Cell Range Extender Powertrain Design on Greenhouse Gases and NOX Emissions in Automotive Applications. Appl. Energy 2021, 302, 117526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usai, L.; Hung, C.R.; Vásquez, F.; Windsheimer, M.; Burheim, O.S.; Strømman, A.H. Life Cycle Assessment of Fuel Cell Systems for Light Duty Vehicles, Current State-of-the-Art and Future Impacts. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 125086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2021; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, G. A Comparative Assessment of Battery and Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles Using a Well-to-Wheel Analysis. Energy 2016, 94, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Method | Economic Evaluation | GHG Evaluation | Scope of Vehicle Emissions Analysis | Vehicle Type | Powertrain | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TDCO | LCC | Cost (CS) | Emissions (EM) | OP | LCA | ECR | BEV | FCEV | ICE | Alternatives | |||

| [33] | LP-SO | X | X | X | PV | X | X | HEV | |||||

| [22] | LP-SO | X | X | X | LCV | X | X | ||||||

| [34] | LP-SO | X | X | X | Bus | X | HEV | ||||||

| [23] | LP-MO | X | X | X | LCV | X | X | HEV CNG | |||||

| [35] | LP-MO | X | X | X | PV | X | X | PHEV | |||||

| [36] | LP-SO | X | X | X | Bus | X | X | ||||||

| [24] | LP-SO | X | X | X | LCV | X | X | ||||||

| Study contribution | LP-MO | X | X | X | LCV | X | X | X | FCEREV CNG | ||||

| Index | Range | Description | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| i | 0 to Nk | The age of the van | Year |

| j | 0 to T | The current year in the planning horizon | Year |

| k | k = 1 (van CNG); k = 2 (van BEV); k = 3 (van FCEREV); k = 4 (van FCEV) | The van’s powertrain type | Dimensionless |

| m | 0 to Nr | The age of the energy supply infrastructure | Year |

| r | r = 1 (charging point for BEV); r = 2 (charging point for FCEREV); r = 3 (HRS for FCEREV bought or produced); r = 4 (HRS for FCEV bought or produced); r = 5 (FCEV and FCEREV hydrogen dispenser) | The energy supply infrastructure type | Dimensionless |

| Parameter | Description | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Nk | Van type “k” ownership period in the fleet. It is possible to set up different ownership periods for each van type (CNG, BEV, FCEREV, and FCEV). | Year |

| T | Planning horizon analyzed. | Year |

| Nr | “r” type energy supply infrastructure asset service life. Each r-type energy supply device has a different service life. | Year |

| rif | Inflation index. | Dimensionless |

| rd | Discount rate (nominal value). | Dimensionless |

| APVjk | The acquisition price in the year “j” of a van type “k”. | EUR/van |

| VDRik | Type “k” van “i” years old depreciation factor. | Dimensionless |

| FCijk | Fixed term of operating costs in the year “j” for a type “k” van “i” years old. | EUR/year |

| VECijk | Fueling costs during the year “j” for a type “k” van “i” years old. | EUR/km |

| MCVijk | Cost of van’s maintenance in the year “j” for a type “k” van “i” years old. | EUR/km |

| RCVijk | Cost of van’s repair in the year “j” for a type “k” van “i” years old. | EUR/km |

| AMijk | Annual mileage demand in the year “j” for a type “k” van “i” years old. | km/year |

| APIjr | “r” type energy supply infrastructure asset acquisition price in the year “j”. | EUR/infrastructure |

| ISRmr | “r” type energy supply infrastructure asset scrapping return value with “m” years of operation. | Dimensionless |

| MCImjr | “r” type energy supply infrastructure asset maintenance costs in the year “j” with “m” years of operation. | EUR/year |

| RCImjr | “r” type energy supply infrastructure asset repairing costs in the year “j” with “m” years of operation. | EUR/year |

| Scope 1 GHG emissions based on the CNG consumption. | kgCO2e | |

| Emission tax in the year “j”. | EUR/kgCO2e | |

| Yearly van CNG consumption. | kg | |

| Scope 2 GHG emissions associated with the purchased electricity. | kgCO2e | |

| Yearly electricity consumption of each van of type “k”. There are only two plug-in vans: BEV (k = 2); and FCEREV (k = 3). | kWh | |

| Scope 3 GHG emissions produced by the electricity acquired (reported in scope 2) due to transmission and distribution losses. | kgCO2e | |

| Scope 3 GHG emissions based on the hydrogen purchased. | kgCO2e | |

| Yearly hydrogen consumption of each van of type “k” n. There are only two vans powered by hydrogen: FCEREV (k = 3); and FCEV (k = 4). | kg | |

| NSIr | “r” type energy supply asset capacity for fueling vans per day. | van |

| PVbj | Budget for van purchasing during the year “j”. | EUR |

| PIbj | The budgetary limit in the year “j” for purchasing an energy supply infrastructure asset. | EUR |

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| VOijk | Van “k” type “i” years old in operation during the year “j”. |

| VSijk | Van “k” type “i” years old sold during the year “j”. |

| VAjk | Van “k” type acquired during the year “j”. |

| IOmjr | Energy supply infrastructure asset “r” type with “m” years in operation during the year “j”. |

| ISmjr | Energy supply infrastructure asset “r” type with “m” years sold during the year “j”. |

| IAjr | Energy supply infrastructure asset “r” type acquired during the year “j”. |

| Modeling Variables | Units | Scenario Nomenclature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | S1 (P/G) | S2 (P/G) | S3 (P/G) | S4 (P/G) | S5 (P/G) | S6 (P/G) | ||

| Hydrogen supply pathway | H2 acquired (P) or H2 on-site electrolysis produced (G) | |||||||

| Corporate emissions reporting option | Scopes 1 and 2 (S12) or scopes 1, 2, and 3 (S123) | |||||||

| Annual mileage | km | 30.000 | 20.000 | 40.000 | 30.000 | 30.000 | 30.000 | 30.000 |

| Van’s ownership period | years | 8 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 10 | 8 | 8 |

| Fleet size | units | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 80 | 320 |

| CNG | BEV | FCEREV | FCEV | Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discount rate | % | 2.5 | - | - | - | (1) |

| Inflation index | % | 1.3 | - | - | - | (1) |

| Van acquisition cost | EUR/van | 37.385 | 51.520 | 51.865 | 71.450 | (2) |

| Maintenance cost (4) | EUR/km | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.11 | |

| Electricity cost (5) | EUR/MWh | 168 | - | - | (3) | |

| Hydrogen cost (5) | EUR/kg | - | - | 4.2 | 4.2 | |

| CNG cost (5) | EUR/kg | 2.7 | - | - | - |

| EF | Comments | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNG () | kgCO2e/kg | 2.8 | [28,52] | |

| Electricity ( | kgCO2e/kWh | 0.25 | (1) | [53] |

| Diesel ( | kgCO2e/L | 2.39 | (2) | [28,52] |

| Hydrogen produced by SMR ( | kgCO2e/kg | 11.8 | [41,54] |

| CNG | BEV | FCEREV | FCEV | Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van model | Fiat Ducato L1H1 | Peugeot e-Expert | - | - | (1) | |

| Powertrain power | kW | 101.4 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Fuel-cell stack power | kW | - | - | 30 | 100 | |

| Storage capacity | kg | 36 | - | 1.5 | 3 | |

| Battery capacity | kWh | - | 75 | 28 | 2 | |

| Vehicle body weight | kg | 1566 | 1576.4 | 1576.4 | 1576.4 | |

| Powertrain weight | kg | 135 | 28.6 | 28.6 | 28.6 | |

| FC stack and peripheral components’ weight | kg | - | - | 25 | 60 | |

| Fuel tank weight | kg | 194 | - | 26 | 53 | |

| Battery pack weight | kg | - | 483 | 180 | 12 |

| EF | Comments | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle chassis | kgCO2e/kg | 4.5 | [50,55,56,57] | |

| ICE motor | kgCO2e/kg | 8 | (1) | [57] |

| Electric motor | kgCO2e/kW | 17 | [55,58] | |

| Traction battery | kgCO2e/kWh | 158 | [50,55,56,59] | |

| Fuel cell system | kgCO2e/kW | 57 | [56,59,60] | |

| High-pressure hydrogen tank | kgCO2e/kgH2 | 640 | [56,59,60] | |

| CNG tank | kgCO2e/kg | 8 | (1) | [58] |

| Parameters | Baseline Scenario Scopes 1–2 | Baseline Scenario Scopes 1–2–3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Units | Value in the Baseline Scenario | Value for Sensitivity Analysis | E (1) | SVO (2) | E | SVO | |

| Annual mileage | km | 30.000 | 20.000 | −0.26 | FCEREV | −0.26 | FCEREV |

| km | 30.000 | 40.000 | −0.51 | FCEREV | −0.86 | MIX (6) | |

| Van’s ownership period | year | 8 | 5 | 0.49 | FCEREV | −0.39 | FCEREV |

| year | 8 | 10 | 0.33 | FCEREV | −0.24 | FCEREV | |

| Discount rate | % | 2.50 | 6 | −0.37 | FCEREV | −0.36 | FCEREV |

| Inflation index | wf (3) | 1 | 2.50 | 0.31 | FCEREV | 0.31 | FCEREV |

| Electricity price (4) | EUR/kWh | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.04 | FCEREV | 0.06 | FCEREV |

| Hydrogen price (4) | EUR/kg | 4.20 | 4.61 | 0.01 | FCEREV | 0.33 | FCEREV |

| CNG price (4) | EUR/kg | 2.70 | 2.43 | 0.04 | FCEREV | 0.05 | FCEREV |

| FC (7) van purchase price | wf | 1 | 1.10 | 0.45 | FCEREV | 0.45 | FCEREV |

| FC (7) van M&R cost | wf | 1 | 1.10 | 0.17 | FCEREV | 0.17 | FCEREV |

| Carbon tax | EUR/ton CO2e | 77.5 | 155 | 0.00 | FCEREV | 0.00 | FCEREV |

| EF electricity | kgCO2e/kWh | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.56 | MIX (5) | 0.25 | FCEREV |

| EF hydrogen | kgCO2e/kg | 0 | 4.72 | - | - | 0.02 | FCEREV |

| Parameters | Baseline Scenario Scopes 1–2 | Baseline Scenario Scopes 1–2–3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Units | Value in the Baseline Scenario | Value for Sensitivity Analysis | E (1) | SVO (2) | E | SVO | |

| Annual mileage | km | 30.000 | 20.000 | 0.16 | FCEREV | 0.16 | FCEREV |

| km | 30.000 | 40.000 | 0.00 | BEV | −0.24 | BEV | |

| Van’s ownership period | year | 8 | 5 | 0.18 | BEV | −0.36 | FCEREV |

| year | 8 | 10 | 0.26 | BEV | −0.21 | FCEREV | |

| Discount rate | % | 2.50 | 6 | −0.37 | BEV | −0.37 | FCEREV |

| Inflation index | wf (3) | 1 | 2.5 | 0.31 | BEV | 0.31 | FCEREV |

| Electricity price (4) | EUR/kWh | 0.17 | 0.19 | −0.07 | BEV | −0.11 | FCEREV |

| CNG price (4) | EUR/kg | 2.670 | 2.43 | 0.04 | BEV | 0.01 | FCEREV |

| FC (5) van purchase price | wf | 1 | 0.90 | 0.02 | BEV | −0.42 | FCEREV |

| FC (5) van M&R cost | wf | 1 | 0.90 | 0.00 | BEV | −0.13 | FCEREV |

| Carbon tax | EUR/ton CO2e | 77.5 | 155 | 0.00 | BEV | −0.01 | FCEREV |

| EF electricity | kgCO2e/kWh | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.61 | BEV | 0.34 | FCEREV |

| Worst-Case Scenarios and Scenario Values | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Units | S13-P | S14-P | S23-P | S24-P | S13DR-P | S14VC-P |

| Annual mileage | km | 20.000 | 20.000 | 40.000 | 40.000 | 20.000 | 20.000 |

| Van’s ownership period | year | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Discount rate | % | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 2.5 | 6 |

| Inflation index | wf (1) | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 1.00 | 2.50 |

| Electricity price (2) | EUR/kWh | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| Hydrogen price (2) | EUR/kg | 4.61 | 4.61 | 4.61 | 4.61 | 4.61 | 4.61 |

| CNG price (2) | EUR/kg | 2.43 | 2.43 | 2.43 | 2.43 | 2.43 | 2.43 |

| FC (3) van purchase price | wf | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.00 |

| FC (3) van M&R cost | wf | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.10 |

| Carbon tax | EUR/ton CO2e | 155 | 155 | 155 | 155 | 155 | 155 |

| EF electricity | kgCO2e/kWh | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| EF hydrogen | kgCO2e/kg | 4.72 | 4.72 | 4.72 | 4.72 | 4.72 | 4.72 |

| PVO (4) | CNG | BEV | FCEREV | FCEREV | BEV | FCEREV | |

| Worst-Case Scenarios and Scenario Values | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Units | S13-G | S14-G | S23-G | S24-G | S13DR-G | S14VC-G |

| Annual mileage | km | 20.000 | 20.000 | 40.000 | 40.000 | 20.000 | 20.000 |

| Van’s ownership period | year | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Discount rate | (%) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 2.5 | 6 |

| Inflation index | wf (1) | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 1 | 2.50 |

| Electricity price (2) | (EUR/kWh) | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| CNG price (2) | (EUR/kg) | 2.43 | 2.43 | 2.43 | 2.43 | 2.43 | 2.43 |

| FC (3) van purchase price | wf | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.10 | 1.00 |

| FC (3) M&R cost | wf | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.10 |

| Carbon tax | EUR/ton CO2e | 155 | 155 | 155 | 155 | 155 | 155 |

| EF electricity | kgCO2e/kWh | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| PVO (4) | CNG | BEV | BEV | BEV | BEV | FCEREV | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castillo, O.; Álvarez, R. Electrification of Last-Mile Delivery: A Fleet Management Approach with a Sustainability Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416909

Castillo O, Álvarez R. Electrification of Last-Mile Delivery: A Fleet Management Approach with a Sustainability Perspective. Sustainability. 2023; 15(24):16909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416909

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastillo, Oscar, and Roberto Álvarez. 2023. "Electrification of Last-Mile Delivery: A Fleet Management Approach with a Sustainability Perspective" Sustainability 15, no. 24: 16909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416909

APA StyleCastillo, O., & Álvarez, R. (2023). Electrification of Last-Mile Delivery: A Fleet Management Approach with a Sustainability Perspective. Sustainability, 15(24), 16909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416909