Abstract

Based on a fixed-point survey of spontaneous space in the Tanhualin area of Wuhan, China, spontaneous space samples were obtained. The spatial typology method was used to summarize and compare the morphological and functional characteristics of the samples, and the space was divided into 10 types and seven functions. Through quantitative statistical analysis of the relationship between different spontaneous space forms and their spatial functions, it was found that residents’ behavior in daily life has a significant effect on spontaneous space renewal and district renewal. Based on the study of the spontaneous space of the Tanhualin historical–cultural district, this study determined the status quo of the space renewal and development of the district and put forward corresponding protection and renewal strategies. Finally, it provides a theoretical basis for the sustainable renewal and coordinated development of historical–cultural districts.

1. Introduction

The historical–cultural districts in a city reflect the local architectural features, the historical culture, and the life characteristics of a region. They are also a link between urban and rural coordinated development, as well as a cultural cornerstone of urban and rural sustainable development. It is a widely accepted fact that urban heritage in a historical–cultural district, including its tangible and intangible components, represents a key factor in enhancing livability, fostering economic development, and social cohesion [1,2]. However, urbanization, global market liberalization, and the market exploitation of heritage can engender the fragmentation and deterioration of cultural heritage [3,4,5,6]. After World War II, under the guidance of the functionalism of CIAM (International Congresses of Modern Architecture), more attention was paid to the adjustment and optimization of industrial structure and production layout, which solved problems such as industrial pollution and crowding brought by industrialization [7]. After the 1970s, urban renewal began to emphasize public participation, and “bottom-up” community planning gradually appeared where community residents volunteered to participate in the renewal of the community [8]. However, China’s urban development since the 1990s has been dominated by the government and the market without public participation. Considering the special cultural attributes of the historical–cultural districts in a city, large-scale demolition and reconstruction are avoided. These blocks are characterized by complex neighborhood relations and lifestyles, which are important samples of local residents’ life activities [9]. At present, there are three main subjects in the implementation of the renovation of urban historical–cultural districts, including the government, market capital, and local residents and social groups. Nowadays, factors restricting the renewal of historical–cultural districts are becoming more and more complex, with a renovation model involving multi-subject participation and cooperation that fully respects the opinions of local residents and preserves the lifestyle and historical texture of historical–cultural districts to a greater extent [10].

Due to the modernism movement, the pursuit of efficiency and geometric space in metropolises led to concrete buildings rapidly coming to occupy a large part of urban space. Nowadays, the effects of rapid and patterned urbanization processes on the original lifestyle of residents, unbalanced and unsustainable urban development, people’s life demands, and the activation of neighborhood vitality have attracted increasing attention. Several studies have highlighted how historical cities’ revitalization requires a long-term commitment to reconfiguring physical space, altering perceptions, and transforming the functions of urban space [11].

In the rapid urbanization process in China, the land property boundary has not been a stable element. China’s urban planning is still at the level of functional zoning, and insufficient attention has been paid to the issue of clear property rights in either the planning stage or the implementation stage, let alone at the legal level of clear property rights [12]. This has led to a lack of supervision and guidance for a large number of “bottom-up”, self-organized, small-scale, incremental updates. Informal construction behavior is particularly prominent in historical–cultural districts. Rapid urbanization in China has brought a large number of people into the cities, and those who cannot afford new houses need to transform old ones to improve their living environment. The root cause of a large number of illegal constructions in historical–cultural districts is poor living conditions, and a lack of funds for the government to improve the living conditions of the old city has led to many problems; for instance, support for public service facilities might be delayed, diverted or they are poorly maintained [13]. Since residents’ daily life needs cannot be met, spontaneous spaces have appeared in large numbers to make up for the inadequacy of existing community functions. The location, form, and function of these spaces also reflect the characteristics of local residents’ lifestyles and behavior. Of course, they also reflect the self-sustaining development process of a city. Therefore, this study took the issue of spontaneous spaces in historical–cultural districts as an entry point to discuss the impact of the form of spontaneous spaces on the development and renewal of historical–cultural districts. By taking the historical–cultural district of Tanhualin as an example, this study sought to understand the updated status of the spontaneous space, spatial form features, and residents’ living habits, and some suggestions for the update of the district are put forward.

2. Regional and Cultural Background of Tanhualin District

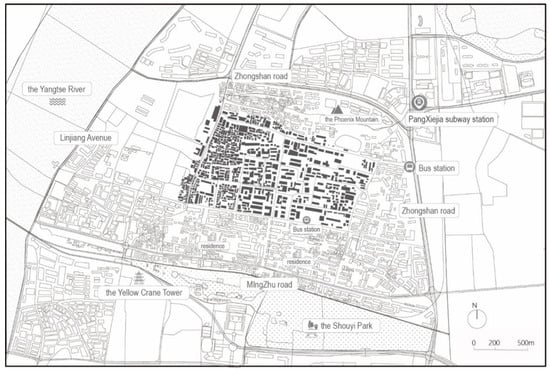

Tanhualin historical–cultural district (Figure 1 and Figure 2) is located in the Wuchang District, Wuhan City, Hubei Province, it is close to Pangxiejia, Phoenix Mountain, and Huayuan Mountain, and it mainly includes Tanhualin Main Street, the Fenghuangshan residential area, the Gejiaying area, the Hansangong area, and the University of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Figure 1.

The location of Tanhualin historical–cultural district in Wuhan, China (left); the area of Tanhualin historical–cultural district (right).

Figure 2.

Scope of survey.

As an important historical–cultural district in Wuhan, Tanhualin is characterized by the coexistence and mutual influence of various cultures. In this area, there are western buildings, such as Wenhua College, Renji Hospital, the Swedish Consulate, and Buddhist temples and Taoist temples with strong religious characteristics. In addition, there are still a large number of old houses of the pre-modern population. After 1949, the houses here were nationalized to accommodate a large number of workers in state-owned enterprises. Since the 1950s, the original private courtyard houses have been divided between several workers’ families, forming a neighborhood lifestyle of multiple households living together. After “The Cultural Revolution” ended and the educated youth returned to the city, the population in this area increased greatly, and a large number of three-generation family units lived in the same house [14]. Due to the increase in population, some residents rebuilt their houses, making the neighborhoods densely populated. A large number of spontaneous spaces (Figure 3) appeared during this period of time, and the functions and forms are constantly changing with the times. It was not until 2004 that the protection of the Tanhualin historical–cultural district was officially included in the urban planning system by the Wuhan government. At present, the main buildings on Tanhualin Main Street have been developed due to the development of tourism. Both sides of the main street have cafes, restaurants, souvenir shops, and handicraft shops. The commercial tourism atmosphere is strong. In the southern part of the main street, however, there are a large number of non-renewed residential areas. After the 1990s, some families moved out of this block. At present, the local residents are mainly elderly and migrant workers. These residential areas still retain the most primitive block forms and the urban lifestyle of the old Wuhan citizens. As an extension of the living spaces, the streets have also given birth to street culture and neighborhood politics, endowing the outdoor landscape with unique urban characteristics.

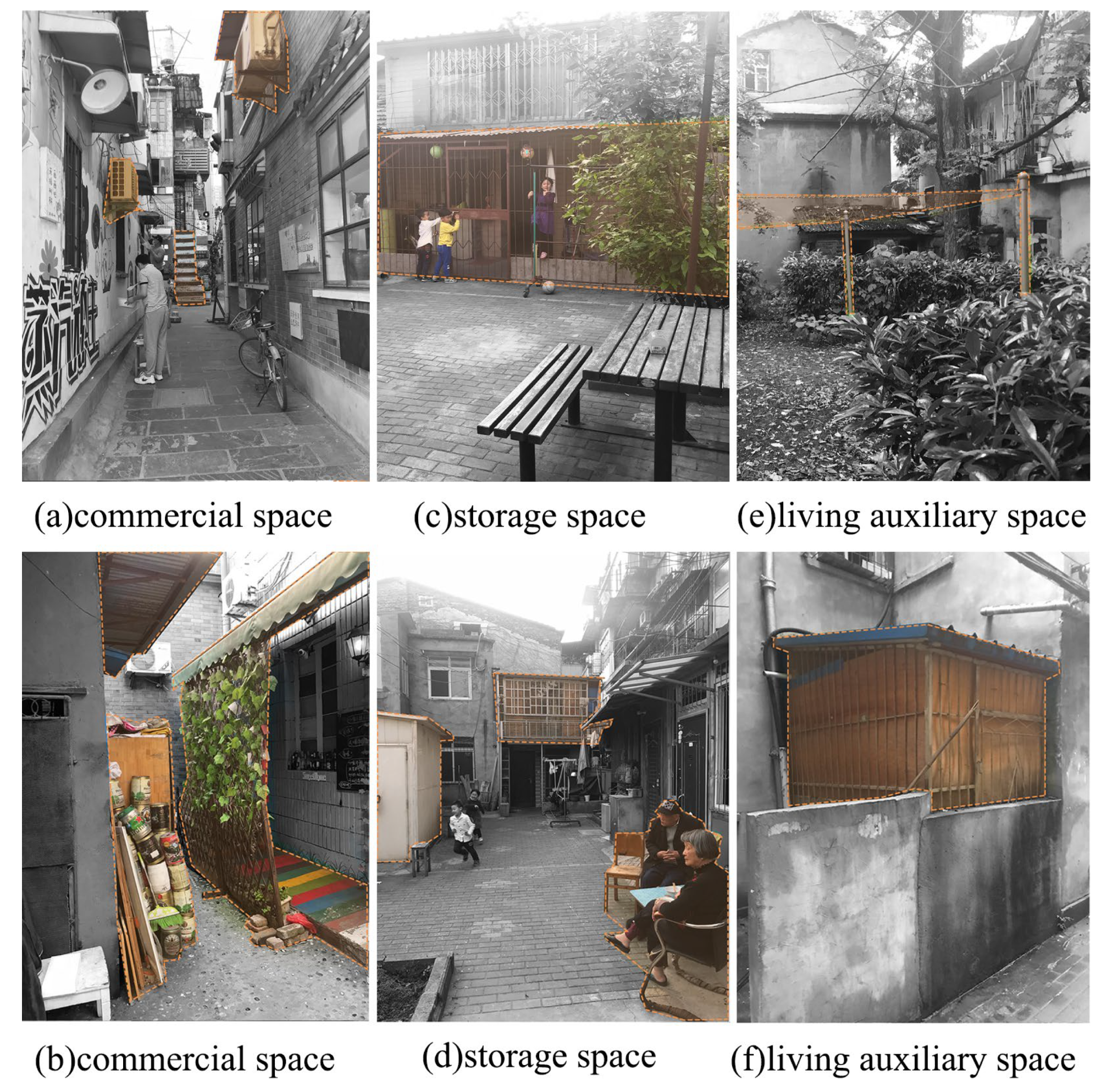

Figure 3.

Spontaneous space.

3. Research Framework and Strategies

3.1. Principle of Spontaneous Space Reflecting Residents’ Life Behavior

The spatial characteristics of spontaneous spaces can accurately reflect the social lifestyle of local residents. The users of a building have been redesigning the building from the first moment they use it. Over time, the use of architectural space is also changing. The daily life behaviors of the local residents in historical–cultural districts have subtle influences on the spatial form of the surrounding streets and architectural spaces to a certain extent. Over a long period of their accumulation in historical–cultural districts, the streets and architectural features of the area will be imbued with obvious spatial characteristics of local social activities. Spatial form reflects social behaviors, and social behavior acts on spatial form in return, showing a relationship of mutual influence.

3.2. Research Framework

The purpose of this study was to understand the renewal status of the historical and cultural block of Tanhualin by investigating the spontaneous space in this district and to put forward some suggestions for updating this area by understanding its spatial form and the residents’ living habits. However, relatively few studies have been carried out on spontaneous space in historical and cultural blocks. Therefore, before this study could be carried out, the first step for setting a research framework was to examine similar studies on the use of spontaneous space in the revival of historical and cultural blocks and in urban micro-renewal as theoretical guidance, including urban micro-renewal and the reconstruction of streets in Copenhagen and Japan [15,16,17,18]. However, considering that any space spontaneously built by residents is actually a manifestation of corresponding measures caused by insufficient living space, the living habits of residents are hidden under its functional logic. Different living habits produce different forms of spontaneous space, so the relationship between spontaneous space and living habits can be established; that is, through studying the form of spontaneous spaces, local living cultures can be understood to a certain extent. Therefore, the second step of this study was to investigate the types of spontaneous space in the block and establish a spatial typology [19,20,21]. The method of formal grammar [22] analyzes spatial characteristics and classifies them and then predicts residents’ living habits with the help of the classified space, which is an innovative link used in this study. In the subsequent steps, it was necessary to judge the different properties of different areas in the historical and cultural block of Tanhualin through the statistical data of spontaneous spatial form classification, such as distinguishing whether they have a strong commercial atmosphere or residential atmosphere and then to propose appropriate renewal or other development strategies for the different areas.

3.3. Research Strategies

Recent typological studies in China have not brought much socio-cultural sustainability to light [19]. There is no quantitative investigation or analysis on the form and function of spontaneous spaces, and there is still a lack of in-depth research on the relationship between the regional characteristics of these spaces and the living activities of residents.

To this end, this paper proposes three strategies for analysis:

- By referring to the relevant literature [19,20,21], the spatial typology method was adopted to classify the types of spontaneous spaces according to the characteristics of their spatial form.

- For the spontaneous spaces, the field investigation method was adopted, and a large number of spontaneous spaces in the Tanhualin district of Wuhan City were investigated from the perspectives of historical factors, types of property rights, construction materials, the composition of the population, and spatial forms and functions.

- According to quantitative statistical methods, the statistical analysis of different morphological characteristics and of the functions of spontaneous spatial division rules was conducted, and then the relationship between residents’ living habits and the spontaneous spaces in the historical and cultural blocks was inferred.

Based on the investigation of the local spontaneous spaces, this work aimed to explore the following three problems: (1) The distribution characteristics and renewal status of local spontaneous spaces. (2) The types of local spontaneous spaces (function and form). (3) The relation between different types of spontaneous spaces and residents’ life behaviors. The contributions of this work are as follows: (1) Grasping the actual needs of residents in this historical–cultural district and providing a theoretical basis for residents to participate in block renewal and management activities in ways that take into account the individualized life needs of local residents. (2) Exploring the personalized renewal plan of different representative areas according to local conditions. (3) For historical and cultural blocks, exploring a sustainable block development path that can meet the development needs of local tourism and the changes in the needs of residents in the block without destroying the buildings or residents’ lifestyles.

This research investigated the spontaneous spaces that blend living and sightseeing functions in the historical block, trying to discover the logic of the life behavior of the local people living in these spaces so as to provide references for the sustainable renewal and renovation of the historical blocks in the urban areas.

4. Implementation of the Research Framework

4.1. Relevant Case Studies

There are a large number of spontaneous spaces in China’s urban areas, which mainly exist in the form of auxiliary space and debris space. In some studies, spaces are mainly divided into two categories: one is physical building spaces that were spontaneously constructed based on residents’ living demands, such as storage rooms, external stairs, and self-built houses; the other is activity venues that are used to meet the needs of daily public activities, such as squares for dancing, bazaars, outdoor sites for playing poker and mahjong, etc. [15]. By returning streets to pedestrians and adding outdoor coffee stands and rest facilities in public spaces, Copenhagen has made the street the venue for a large number of commercial and cultural activities, such as celebration performances and flea markets [16]. Japan put forward the concept of community building in 1957. In densely built-up residential areas and historical–cultural districts, on the one hand, public housing was implemented to promote the reconstruction of old housing and the widening of roads; on the other hand, workshops were carried out via NPOs (nonprofit organizations) and PPPs (public–private partnerships) to attract residents’ participation, absorb the opinions of the local people and organize regional reconstruction [17,18]. The urban planning proposals proposed by citizens were fully supported in terms of organization, professional knowledge, and funds [23]. In historical–cultural districts, regulations for the functions, styles, and colors of the spaces in front of private residences were formulated [24] so that the private spaces of the residents are updated in an orderly manner without destroying the original features of the historical–cultural districts. The above research only focused on the factors affecting informal construction behaviors and the morphological characteristics of spaces in traditional dense commercial blocks and paid less attention to daily life activities and pure living spaces [25,26].

4.2. Field Investigation and Sample Analysis

Many studies on the urban type and street morphology of informal urban spaces have been conducted [27,28]. That work mainly studied the extraction and classification of different types of block buildings [29,30], the uses of residents’ communication spaces [31,32], the analysis of spontaneous spaces in combination with the study of formal grammar [22] and the relationship between the form and function of spontaneous spaces.

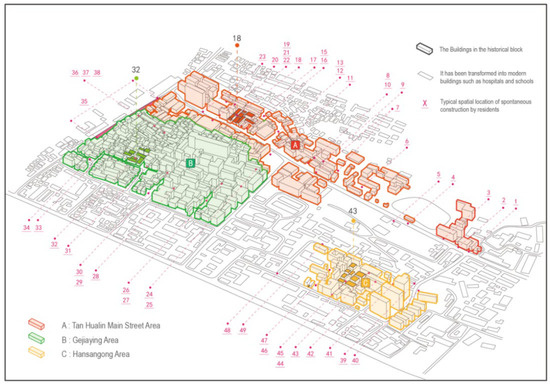

This work was conducted in April 2018 through a field investigation of the Tanhualin historical–cultural district (due to the difficulty of investigation in the Phoenix Mountain area, this survey did not include that area). First, the renewal stage and spatial characteristics of the spontaneous spaces in three distinctly different areas (Figure 4), including the Tanhualin Main Street area (A), the Gejiaying area (B), and the Hansangong area (C) (which will be referred to with the corresponding letters when the three areas appear below), were studied. Then, the locations of 49 spontaneous space samples (Figure 4) were determined using the method of spatial typologies, taking the typical breakthrough street texture and building outline as the judgment conditions. These spaces have typical characteristics of spontaneous space and are closely related to the residents’ daily life. The form and function of 192 spontaneous spaces were surveyed. A total of 279 photos were taken, of which 241 were valid photos. (Because of the large number of external clothes-drying poles, those facilities with the same form on the same building facade were regarded as one place in the survey.) Finally, a field investigation on the locations of representative spontaneous spaces was conducted. Through factor linkage, the connection between space and residents’ living habits was analyzed to elucidate the status quo and causes of these spontaneous spaces. Based on the results of the field investigation, using quantitative statistics (with a factor as an invariant) and combined methods, statistical analysis was carried out from three aspects: one was the proportions of spaces in different renewal stages, based upon which the renewal stage of the whole area could be determined; the second was the percentages of spontaneous spaces with different forms and different functions among the total number, based upon which the quantitative characteristics and the degree of resident demand for certain types of space could be determined; and the third was quantitative statistics for the function of spaces based on the same form, seeking to determine the connection between the spontaneous space’s form and its function.

Figure 4.

Survey points of Tanhualin historical district.

5. Results

5.1. The Renewal Situation of Spontaneous Space in the Region

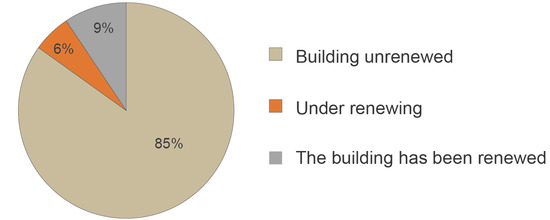

In terms of determining the renewal level, we needed to figure out whether part or all of the functions of a building had changed. There were obvious differences in the renewal levels in the three areas. The renewal level of area A was the highest, that of B area was the lowest, and that of C area was moderate. Generally speaking, the renewal level of the entire Tanhualin district was low (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Renewal ratio of Tanhualin historical district.

The spontaneous space in area A was generally a mixture of residential and commercial. The area close to Zhongshan Avenue was mainly residential. Since the street height-to-width ratio D/H [33] was close to 1, the space was more open where leisure tourism was more diversified. As the ground space was occupied by commercial activities and tourists, the spontaneous spaces extended spontaneously upwards and to the sides of the street, presenting temporary space characteristics. The spontaneous spaces in this area had a low degree of space occupation and more strict control of space boundaries. Near the western boundary of Tanhualin, the commercial atmosphere has become strong in recent years. There is a certain degree of tourism and commercial development in this area, and there are obvious cultural and boundary characteristics in the renovation of commercial shops and ground paving. The spontaneous spaces were mostly extensions of the commercial spaces and were affected by commercial activities. In area A, the form of spontaneous space was relatively regular, although, in the area that is not directly adjacent to the main street, the spontaneous spaces were in various forms, showing multiple forms in function, color and interrelationships.

Area B was an area where the number and types of spontaneous living spaces in the Tanhualin historic district were relatively concentrated. Due to the changes in the topography, the spaces in this area were also complex. Due to the high density of buildings in this area, the streets usually can only accommodate one or two people abreast, so the spontaneous spaces concentrated in this area often take forms of leaping over the street, corner enclosures, and gap spaces between two buildings. The use of some spaces had been extended to the roof. This area fully reflects the local residents’ pursuit of more living space, and each household mimics and restricts the others around it, forming a unique spatial logic. The space is partly open and partly closed, and the public and private spaces are intermingled, reflecting the stable social relations formed by the local people over a long time.

The function of spontaneous spaces in Area C was relatively more complicated. Due to the complex social environment of the area, the Hubei Academy of Fine Arts, the Hubei University of Chinese Medicine and Wuhan Middle School are located around it. Under the influence of the Hubei Academy of Fine Arts, there were many shops related to art studios and art on the side of Zhongshan Avenue. Studios and cafes in this location were at a high level of renewal. In the center of area C, there was still a relatively complete residential living area. Compared with the other two areas, the scale of the buildings and streets in this area was relatively moderate, and there were also many historical buildings. Area C was a buffer area between traditional blocks and modern urban space.

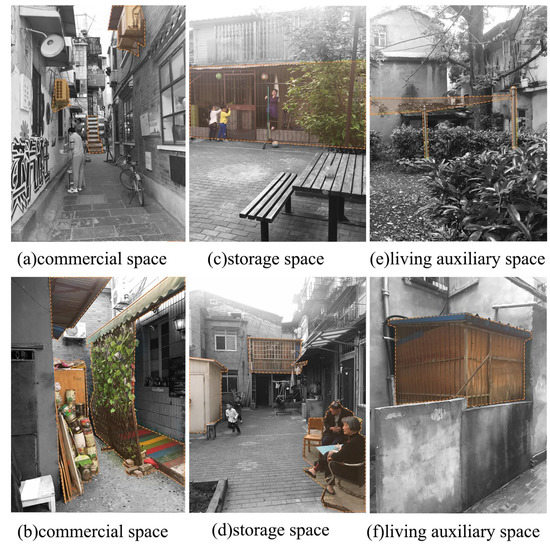

5.2. Analysis of the Living Logic of Local Residents in Spontaneous Spaces

5.2.1. Quantitative Statistics of Spontaneous Spaces with Different Functions and Forms

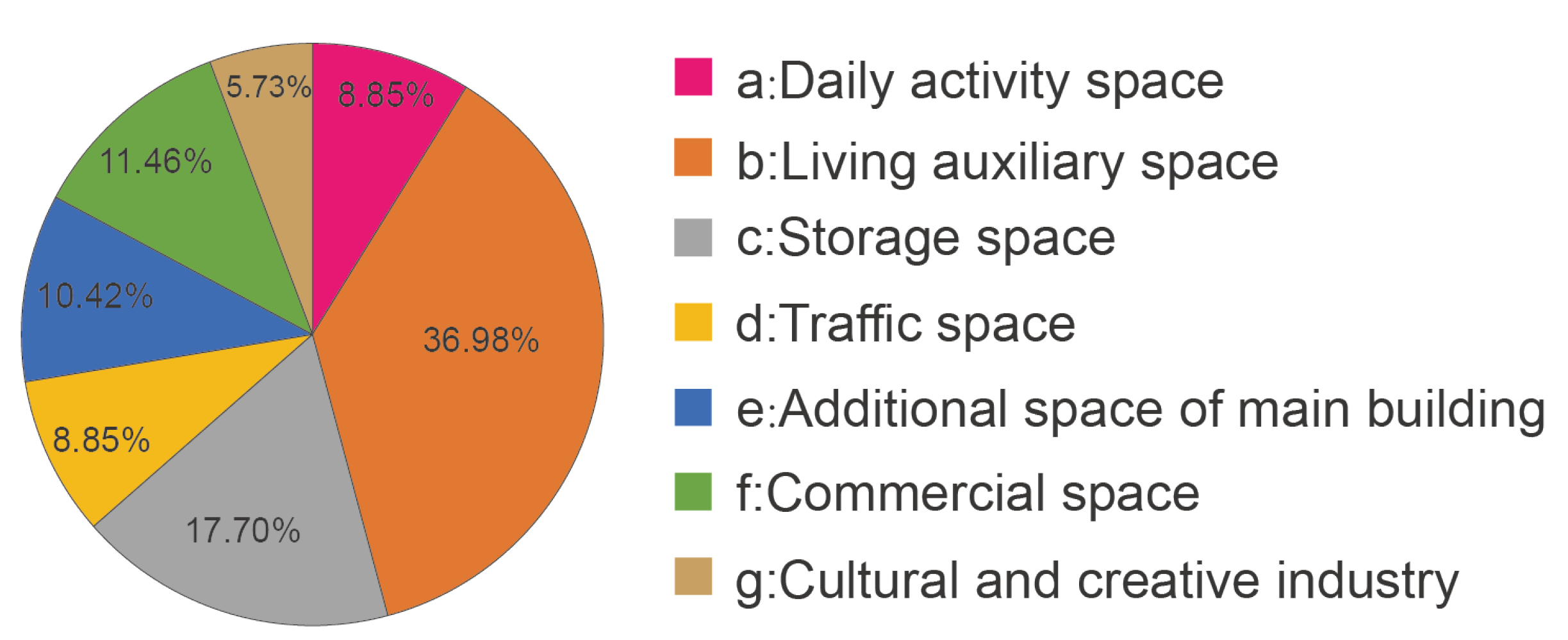

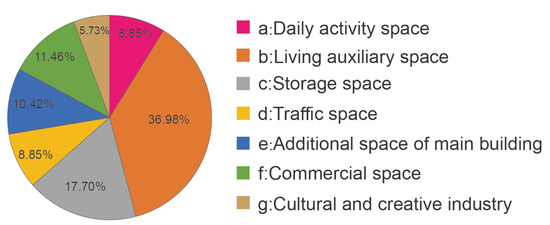

According to the functions of the spaces, the 192 spontaneous spaces in this area were divided into seven types: a daily activity space, b living auxiliary space, c storage space, d traffic space, e additional space of a main building, f commercial space, and g cultural and creative industry space. There were 17 spaces of type a, accounting for 8.85% of the total; 71 of type b, accounting for 36.98% of the total; 34 of type c, accounting for 17.70% of the total; 17 of type d, accounting for 8.85% of the total; 20 of type e, accounting for 10.42% of the total; 22 of type f, accounting for 11.46% of the total; and 11 of type g, accounting for 5.73% of the total (Figure 6). It can be concluded from the statistical results that in the entire Tanhualin district, the highest proportion of spontaneous spaces was living auxiliary spaces (including spaces for clothes hangers, spaces for garbage dumping, spaces for flower ponds and potted plants and multi-purpose spaces), followed by independent spaces for storing goods and materials. The spontaneous spaces in this district reflect the living needs and living conditions of the local residents. Many of the living needs of residents in this district are not met, so building the necessary space for daily life is the biggest incentive for building by the residents in this district. Due to the stimulus brought by the tourism industry and surrounding universities, the spontaneous spaces for business and cultural industries also occupy a certain proportion of the total.

Figure 6.

Proportions of spontaneous spaces with different functions.

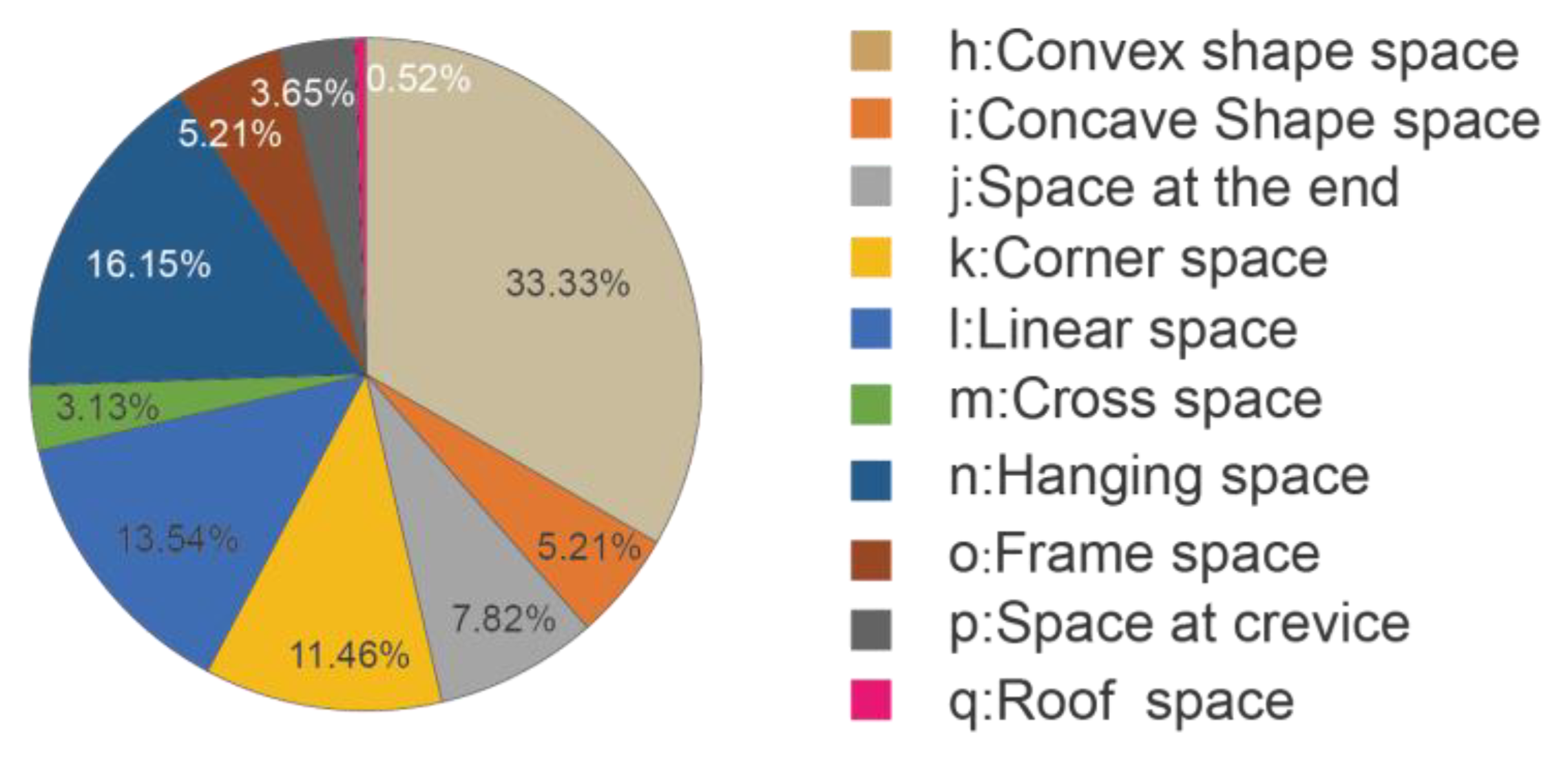

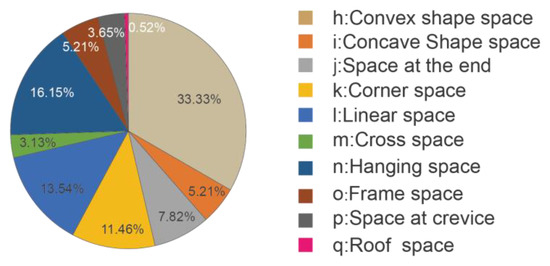

For the forms of the spaces, the 192 spontaneous spaces in this area were divided into nine types: h convex shape space, i concave shape space, j space at the end, k corner space, l linear space, m cross space, n hanging space, o frame space, p space at the crevice, and q roof space. There were 64 spaces of type h, accounting for 33.33% of the total; 10 of type i, accounting for 5.21% of the total; 15 of type j, accounting for 7.82% of the total; 22 of type k, accounting for 11.46% of the total; 26 of type l, accounting for 13.54% of the total; 6 of type m, accounting for 3.13% of the total; 31 of type n, accounting for 16.15% of the total; 10 of type o, accounting for 5.21% of the total; 7 of type p, accounting for 3.65% of the total; and 1 of type q, accounting for 0.52% of the total (Figure 7). The convex space was the most common space form, occupying ground-level space in the street, and the second most common space was the hanging space, occupying the space above the street. Over a long period of continuous accumulation, these kinds of occupation have extended on the ground, the sides, and above the street, and even extend to the adjacent buildings and the opposite buildings. The context of these spaces was intricate, and this kind of encroachment was restricted by the development of neighborhood relations.

Figure 7.

Proportions of spontaneous spaces in different forms.

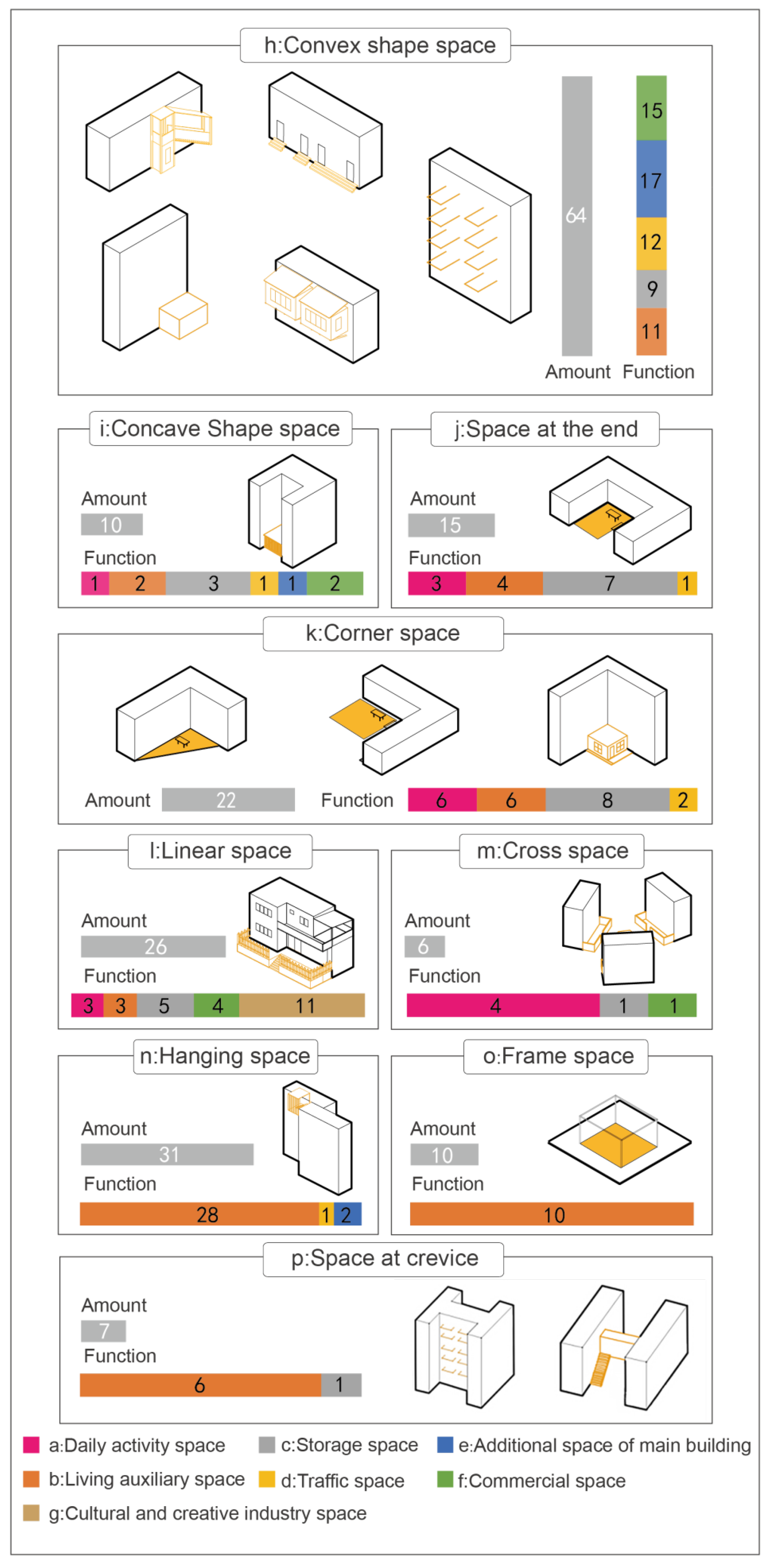

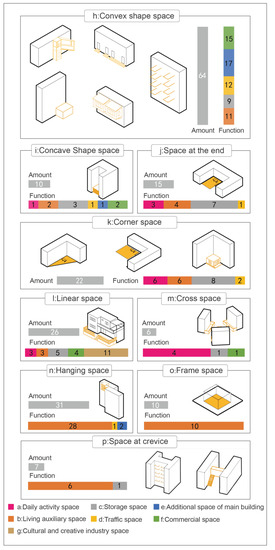

5.2.2. Analysis of the Characteristics of Residents’ Behavior from the Statistical Results of the Number and Functions of Spontaneous Spaces in Different Forms

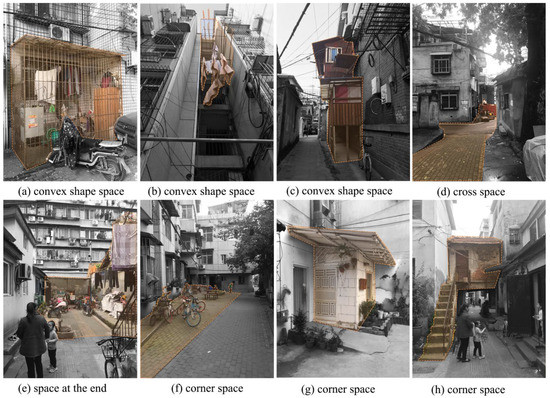

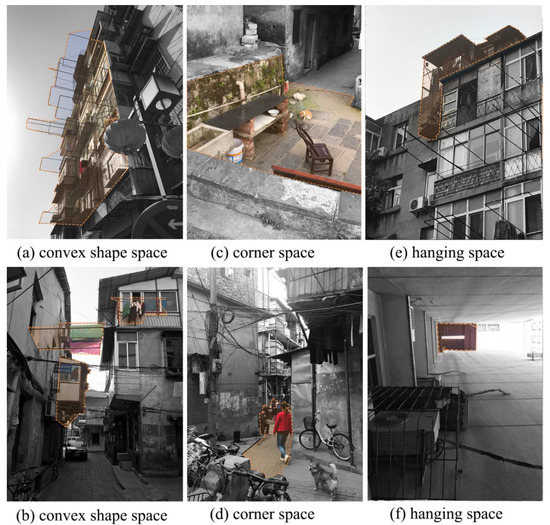

Spontaneous space is not so much the result of the re-planning and re-arrangement of space as it is of the game and balance in neighborhood relations. Therefore, the function and morphological characteristics of spontaneous space are often adapted to the street form and the surrounding environment, so that its final spatial effect can meet the psychological needs of the neighbors. The spatial function and spatial form often influence each other, and the determinants for the formation of the spontaneous space are people’s understanding of the spatial boundaries of the place and the psychological division of the boundary between the private and public spheres. This is one of the most important differences between spontaneous spaces and other types of spaces. Sixteen typical spontaneous space samples in the Tanhualin district of Wuhan were obtained and then classified according to their form. Moreover, their functional characteristics were analyzed (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Statistics for spatial functions of spaces having the same form.

Tanhualin’s spontaneous spaces have the following seven characteristics that are different from those designed and built by architectural practitioners: (1) They mostly appear in batches. (2) They are more common in corners, edges, and end spaces. (3) They mostly appear on the side of the street. (4) They are attached to the main building. (5) They have less impact on street space. (6) Their boundary is blurred. (7) They often cater to the shape of surrounding buildings.

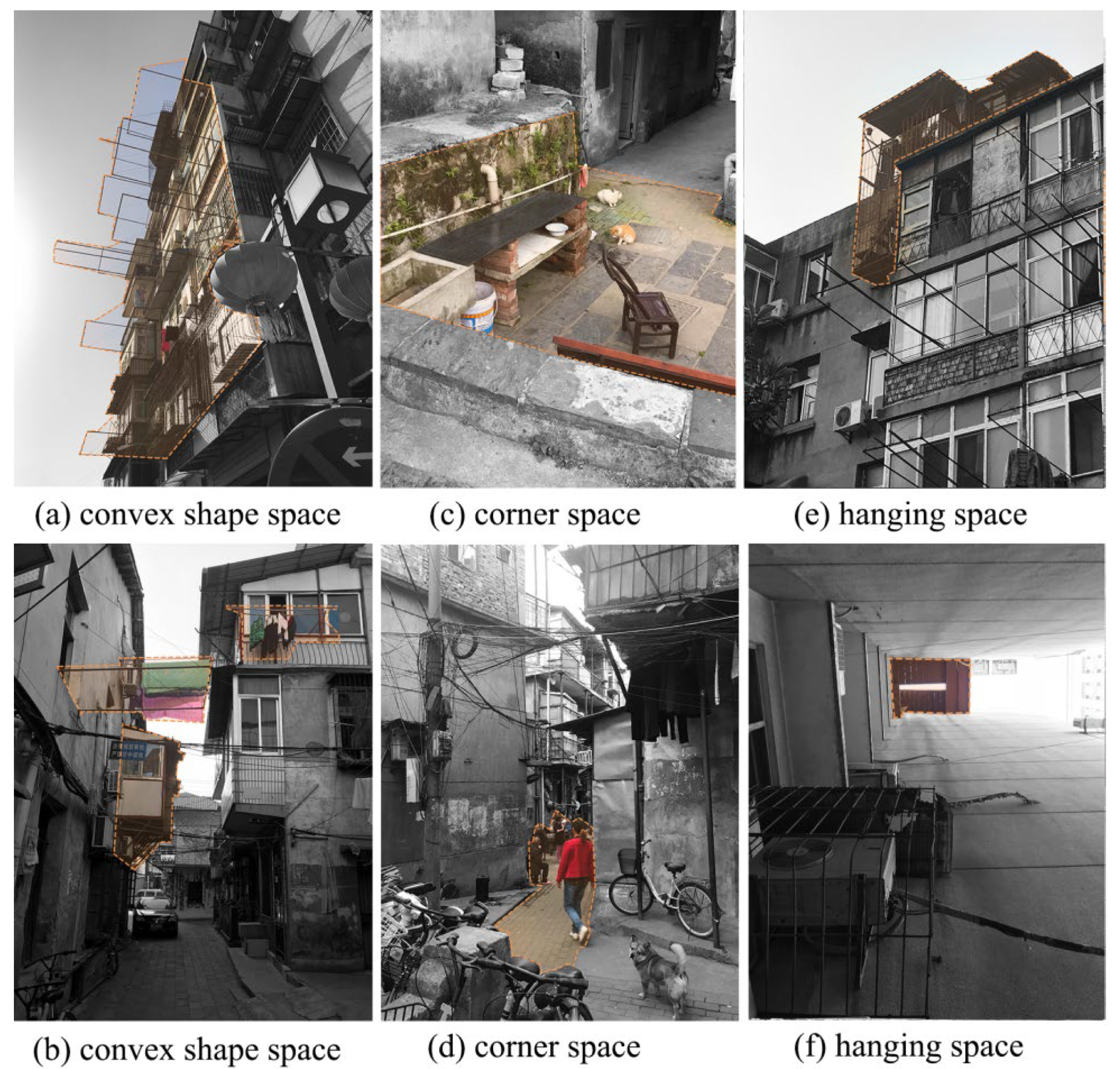

For the h convex shape space (Figure 9a,b), the e externally convex space of the main building was the most common spontaneous space. Since it is an architectural addition, it often extends from the architecture’s noumenon, so the convex form is naturally generated. With the function of gathering people and attracting consumption, the f commercial space naturally presents a certain convex form. Due to the large volume of traffic and the function of connecting two or more architectural spaces, the d traffic space inevitably causes a certain degree of convexity. In this study, the degree of convexity of traffic spaces was relatively limited, as most spontaneous spaces tried to minimize their impact on the surrounding buildings and streets as much as possible. The i concave space only accounted for 5.21% of all spontaneous space samples. Since spontaneous space is often created to meet the needs of local residents’ life, concave space is not the first choice. Therefore, concave space often appeared in areas with complex external environments and narrow spaces, where it was a compromise space style.

Figure 9.

Spontaneous space.

The j end space refers to the closed space at the end of a certain site or street. This type of space spatially divides the site into an inside site and an outside site. The inner corner space formed by multiple enclosures has a certain degree of privacy and centripetality. Compared with other end spaces, the end space for a daily activities has a larger scale. In terms of function, such end spaces can be used for activities such as sunbathing, talking, games, etc., for the elderly and children, while other end spaces are often small or occupy only a part of the end position. The k corner space (Figure 9c,d) is often more prone to conflicts and contradictions due to the fuzzy borders with adjacent streets. In the corner space, there are both personal enclosed spaces and open public spaces, as well as ambiguous spaces with unclear spatial functions. In terms of emotional experience, the corner space is a hybrid composed of a chaotic, noisy, and impersonal external environment and a personal, quiet, imaginative, and poetic internal environment, and encompasses many aspects of life. Corner spaces have a certain degree of enclosure, but they are not completely enclosed. Therefore, this type of space is a relatively neutral space with both private and public characteristics at the same time. Moreover, it presents diversification in terms of functions and users. There were two main types of l linear space: one was f commercial space and g cultural and creative industry space, which had a higher level of renewal, and the other was objects arranged along the street and bottom of buildings, such as flower beds, storage shelves and other objects, which have the characteristics of movability and weak enclosure of space. The spontaneous space of m cross space is often confronted with a contradiction between closure and communication. Therefore, this place is rarely used as a closed and independent space, but more as a space for the daily activities of residents. In the n hanging space (Figure 9e,f), a large number of clothes-drying poles has a great impact on the upper space of the street, and some of these even completely occupy the space above the entire street. Since the Tanhualin district itself is densely built with multiple shadow corners and less space per capita, the length and height of the clothes-drying poles were large so as to obtain enough sunlight. This type of space changes the street skyline, and it enriches the second contour line of the buildings together with the additional architectural space, forming a unique relationship between light and shadow. Such a pattern of space should be re-innovated in Tanhualin district renewal. A total of 10 o frame space samples were found during the investigation, all of which were b living auxiliary spaces, most of which were square three-dimensional frame structures. This type of space often appeared in enclosed courtyards or in large open spaces, which led to strict limits on site size and topography. The p gap space mainly refers to space that results from the contradiction between site restriction and people’s needs. This type of space is often shared by two or more families, which reflects the rebalancing of external space as well as the living wisdom of local residents.

5.3. Research on the Spontaneous Spaces of Three Representative Areas

The survey results showed that the spontaneous spaces in the Tanhualin district were mainly affected by commercial behavior, residents’ living needs, and the surrounding historical buildings. From the perspective of these three issues, in-depth research was conducted on the spontaneous spaces in three representative areas (survey sites 18, 32 and 43) (Figure 4).

The No. 18 survey site was a commercial area (Figure 10a,b). A curry restaurant was located in the center of this alley. With the development of local tourism, this restaurant attracted tourists by applying graffiti art and other art treatments on the facade of the original building and by adding building entrances along the street. The spontaneous construction at this site was due to the business opportunities brought about by tourism, which gradually changed the original function of the building. In terms of space form, this type of space was located near the main street, where there was a strong commercial atmosphere. The space along the street gradually turned from a closed state to an open state, and the space was revived by commercial means. With the continuous enrichment of functions, the demand for storage and transportation space had increased, resulting in the formation of many commerce-related spontaneous spaces. The No. 32 survey site was a residential courtyard (Figure 10c,d). The spontaneous space in this area was dominated by daily activity space and storage space. Since it was a multi-household living space centered on a courtyard, local residents had a strong sense of mutual trust and close neighbor relationships. Residents did not have clear space usage boundaries in the use of courtyard space. The storage space was mostly separated by iron metal frames, and most of them were simple space divisions without too much obstruction of the line of sight, which made it a relatively open space. At the same time, it also reflected the positive correlation between the intimacy of neighborhood relations and the openness of spontaneous spatial forms. The unique spatial form created by the metal frame storage space in the courtyard not only had storage functions but also enclosed space for daily activities for children and the elderly. The entire courtyard became an interior space for the residents. In this courtyard, the small space in front of each door was a further internal space. The spontaneous space in this area was not only a specific functional space but also a part of the space boundaries. The survey site No. 43 was located around historical buildings (Figure 10e,f). Due to the protection of the historical buildings, the density of residents in this area was low, and residents generally lived away from the historical buildings. Therefore, it was not necessary here for residents to create spontaneous spaces to meet their basic needs in life. The spontaneous spaces in this area were mainly for vegetable gardens, clothes drying, and vehicle parking rather than basic life activities. The spontaneous spaces here were less affected by relationships between neighbors, but they were greatly affected by the protection of the historical buildings. There was a lot of unused space, and the area had high autonomy and development potential.

Figure 10.

Spontaneous space.

6. Discussion

6.1. Positive Influence

The results of this work fully illustrate the importance of residents in the renewal of historic districts. Increasing the participation of residents in the renewal and transformation of blocks is the most important way to protect the local landscape and local residents’ lifestyles. Communication between the government, the real estate companies, and the local residents can be strengthened by establishing community non-governmental organizations, and this also can improve the system of sustainable urban and rural development. Through the collection and sorting of residents’ spatial images, those residents become the main design subjects, and the blocks can be renewed through the use of design games [34]. Although a historical–cultural district is rooted in the city, it is continuously changing and is neither static nor uniform [35]. Morphologists explain these changes in urban form in typological studies as cumulative and continuous and consider continuities of urban form and typological transformation as enhancing socio-cultural sustainability and benefiting people’s satisfaction with life there [36,37,38].

The results of that work emphasize the important role of residents in the renewal of historical and cultural districts and at the same time, put forward residents’ demands concerning the process of renewal, providing a theoretical basis for the implementation of bottom-up block renewal practices in order to link urban and rural coordinated development.

6.2. Limitations and Prospects

This paper used a typological approach as the tool to establish an analytical framework from a spatial form perspective to focus on the historical–cultural districts in a city, and it investigated the type, function, and form characteristics of spontaneous space therein. Through a survey of the general situation of local blocks, as well as of the living style of residents, this study revealed the relationship between spatial characteristics and human behavior. On this basis, further research on the spontaneous spatial evolution process of a street and on the renovation of the interior space of a single building is needed. Based on the research results of spontaneous space presented here, the renewal and renovation mode of blocks involving multi-party participation needs to be further explored.

7. Conclusions

Under the mode of urban renewal in China, the renewal of the historical–cultural district of Tanhualin will inevitably have the trend of being devoid of cultural connotations, and the district will become a modern district with antique architecture but no cultural connotations. This research was intended to help preserve the characteristics and cultural connotations of the districts, aiming at studying the spontaneous space and residents’ living habits, determining the updated status of the spontaneous space in the district, and elucidating the life logic of the people in the district; finally, certain strategies for the renewal of the Tanhualin district, to realize the sustainable renewal of the spontaneous space and the preservation of the life and culture information in the historical–cultural district of Tanhualin, are put forward.

This research found three main reasons why the Tanhualin district had such abundant examples of spontaneous space: (1) Due to the multiple changes in the population structure in this area, the local residents changed from single-family housing to multi-family shared by factory workers. After that, a large number of educated youth returned to the city, the young population moved out, the elderly stayed behind, and migrant workers moved in, leading to a complex neighborhood relationship; (2) This area has experienced multiple changes in the property rights system, and unclear property rights have led to a large number of self-construction activities; (3) China’s rapid urbanization has led to a serious lag in the creation of living infrastructure for the residents of urban historical and cultural districts, which has led to spontaneous construction behaviors by residents. Regarding the renewal of the district, the research results show that the overall renewal level of Tanhualin district is low and that the living spaces and social activities of a large number of original residents are preserved, which are worthy of being protected. Area A had commercial and residential dual-use space generated by the spontaneous transformation derived from the development of tourism and has high research value for understanding the commercialization of existing residential space. Area B was mostly a spontaneous space serving residents’ daily life activities under dense living conditions, which reflects the changes in China’s contemporary lifestyle and the residents’ wisdom for coping with these changes. In order to better meet the living needs of local residents, these spaces should be used as a reference for the local blocks’ renovation. Area C had low building density because of the multiple famous historic buildings there. The spontaneous space in this area was mainly used for the art and culture industry, which has great potential for tourism development.

As for the renewal strategy, this study found that residents’ behavior is an important factor in shaping the street texture. In the renewal of street texture, the spontaneous space generated by residents leads to the renewal of important and most-used districts, which requires full respect for residents’ lifestyles and the spontaneous space generated by life. The behavior of residents is an important factor in shaping the texture of the block. The protection and renewal of the street texture is an important part of protecting the overall style of historical and cultural districts. Taking the Tanhualin district as an example, area A, with a relatively spacious street, is suitable for the development of tourism and commerce. Adjustments in this area can be made according to the existing commercial space distribution and current business conditions. In area B, there are many small roads, the sense of nodes is rather vague, and road classification needs to be planned. The street texture can be repaired in conjunction with the renovation of single buildings. According to the quantitative statistical data of spontaneous space and function under the guidance of spatial typology, convex space, corner space, and linear space have become spaces that can provide suitable environments for commercial development. Therefore, in order to improve the vitality of the Tanhualin historical–cultural district, it is necessary to increase these types of spaces in an orderly way and provide them with modernizing transformation. However, among the spaces reflecting residents’ living habits, auxiliary living spaces, storage spaces, additional buildings, and commercial buildings account for a relatively high proportion, but the number is still insufficient. Therefore, the sustainable renewal of spontaneous space in historical–cultural districts should moderately increase the numbers of these spaces so as to meet residents’ daily living needs and realize the sustainable development of human connections in historical–cultural districts. The existing spontaneous spaces at the ends, corners, and three-way intersections in the Tanhualin district are used as important node areas. Cultural landmarks such as cultural bookstores, art exhibition halls, and small theaters can be set up in the nodes to promote the vitality of the region and enable interaction between the region and the city [39,40]. In addition to the ground level of the street, a large number of clothes-hanging poles in the Tanhualin district form a unique landscape. In the renewal of historical districts, this element can be fully utilized instead of being dismantled. In fact, these elements can be used to promote cultural slogans, display the Wuhan culture and form a unique skyline. Regarding the renovation of single buildings in historical and cultural blocks, the functional and formal characteristics of the residents’ living spaces obtained in this work are similar to those of historical blocks in other cities. During the renewal process for these blocks, the personalized living needs of local residents should be maintained to the highest degree possible by analyzing the spontaneous spatial characteristics. In addition, as the residents’ needs for living space will change with their age, the blocks should also be renovated considering the age of residents [41]. A certain amount of flexible space can be provided, allowing residents to adapt it flexibly according to their housing needs in different periods.

Preserving the spontaneous space generated by residents’ living habits in historical–cultural districts provides an environment conducive to the cultural development of the districts, promotes vitality for street renewal, and becomes the cornerstone of the sustainable development of historic districts. Through the study of the interface characteristics of spontaneous space in historical–cultural districts, the living demands of residents were reflected, and new references were provided for the development of residential buildings.

Author Contributions

W.S. provided extensive guidance for the research and writing the paper and also translated the first draft. C.H. conducted most of the research on the topic, wrote the original draft, created the charts, and submitted the article. S.L. participated in the basic research work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our thanks to Ding Xianglu and LAN Haifeng for their efforts in the preliminary research and also thank Cheng Huiying for her suggestions on image processing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ewing, R.; Hajrasouliha, A.; Neckerman, K.M.; Purciel-Hill, M.; Greene, W.H. Streetscape Features Related to Pedestrian Activity. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2015, 36, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Handy, S. Measuring the Unmeasurable: Urban Design Qualities Related to Walkability. J. Urban Des. 2009, 14, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.G.; De La Calle-Vaquero, M.; Yubero, C. Cultural Heritage and Urban Tourism: Historic City Centres under Pressure. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.E. Rethinking the conflict between landscape change and historic landscape preservation. J. Herit. Tour. 2015, 11, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen-Verbeke, M. The territoriality paradigm in cultural tourism. Turyzm 2009, 19, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau, C.; Annunziata, A.; Yamu, C. The Multi-Method Tool ‘PAST’ for Evaluating Cultural Routes in Historical Cities: Evidence from Cagliari, Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, J. The urban renewal evolvement since modern times and thought of nowadays China urban renewal. Urban Probl. 2003, 5, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K. Developing Processes of Western Urban Renewal and its Enlightenment. Urban Plan. Rev. 1998, 1, 59–61+51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Y. Preservation and Planning of the Historic Block. Urban Plan. Forum 2000, 2, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S. The Pattern of Renewing and Implementation Way in the Historical Block. Huazhong Archit. 2020, 38, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Liu, G.; Yuan, H.; Song, Q.; Yang, M.; Luo, D.; Zhang, X.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, Y. Evaluation and Scale Forecast of Underground Space Resources of Historical and Cultural Cities in China. Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Lai, S. Property Right Reorganization And Spatial Remolding: Guangzhou Old City Renovation From Land Property Right Viewpoint. Planners 2013, 29, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Informal Housing and Community in Chinese Megacities: Types, Mechanisms and Responses. Urban Plan. Int. 2019, 2, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H. Self-organized Renew Phenomenon in Hybrid Historic Neighborhoods Update and Its Implications: Tanhualin Neighborhoods in Wuchang Old City for Example. Art Des. 2015, 7, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X. Exploration on Micro-renewal of Urban Public Space Based on Community Building. Landsc. Archit. 2019, 26, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, M. The contested public space of shopping streets: The case of Købmagergade, Copenhagen. J. Landsc. Archit. 2017, 12, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Zhai, G.; He, Z.; Gu, F. Experience of community construction in Japan and enlightenment on historical block protection in China: A case study of Furukawa-cho in Japan. Urban. Archit. 2018, 11, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, F.; Saio, N. A Study of the place peculiarities of exchange activities in Urban-Rural Area: Case study of machizukuri-NPO activities in Tsukuba. J. Rural. Plan. Assoc. 2009, 27, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, B. Changes of Spatial Characteristics: Socio-Cultural Sustainability in Historical Neighborhood in Beijing, China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jive’n, G.; Larkham, P.J. Sense of place, authenticity and character: A commentary. J. Urban Des. 2003, 8, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Building institutional capacity through collaborative approaches to urban planning. Environ. Plan. A 1998, 30, 1531–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.A. Informal Settlements: A Shape Grammar Approach. J. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2014, 8, 1389–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashizaki, Y.; Fujii, S.; Arita, T.; Omura, K. A study of application and promotion of the urban proposal system by citizen initiatives. City Plan. Rev. 2007, 42, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, R.; Sano, Y.; Okazaki, A.; Takamizawa, K.; Aiba, S. The Actual Conditions of Design Revuew by Ordinance to Control Townscape. Urban Plan. 2003, 17, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y. Hanzhengjie: An Informal City. Time Archit. 2006, 3, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Nonnormal City: Neglected Problem in the Study of Chinese Urban Renovation. Huazhong Archit. 2008, 26, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Informal construction in Beijing’s old neighborhoods. Cities 1997, 14, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Ross, K. Forms of Informality: Morphology and Visibility of Informal Settlements. Built Environ. 2011, 37, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Satoh, S. A Study on the Analysis of Block Transfiguration with the Change of Site Use a study on the theory of urban architectural block design with methodology of urban morphology Part 1. J. Archit. Plan. AIJ 2007, 621, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Satoh, S. A Study on the Analysis of Block Transfiguration with the Change of Site Use a study on the theory of urban architectural block design with methodology of urban morphology Part 2. J. Archit. Plan. AIJ 2008, 632, 2131–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidokoro, T.; Toriumi, Y. Formation of Social Ecosystem Space of Informal Settlements in the Case of Dharavi in Mumbai, India Focusing on social interaction space. J. Archit. Plan. AIJ 2013, 687, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, R.; Goto, H.; Sakuma, Y.; Uehara, Y. Change in Townscape as Seen from Their Transition of Spatial and Usage Boundary-In Case of “Billboard Architecture” at Hirosaki City, Aomori. J. City Plan. Inst. Jpn. 2004, 39, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashihara, Y. The Aesthetic Townscape; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Shimura, H.; Tatsumi, K.; Satoh, S. A Study on Development of Design Conference Tools by Integrating Goal Image: Development of the method for community design conference by means of the rebuilding design game. J. Archit. Plan. Environ. Eng. AIJ 2002, 558, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepe, M. Principles for Place Identity Enhancement: A Sustainable Challenge for Changes to the Contemporary City; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Thwaites, K. Chinese Urban Design: The Typomorphological Approach; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. Human Aspects of Urban Form: Towards a Man—Environment Approach to Urban form and Design; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, Y. The Practice of Morphological Method in the Conservation and Restoration of Historic Districts—The Case of Urban Design in Shanghai’s Historic City Core. Urban Plan. Forum 2007, 1, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, C. Micro-Regeneration of a Historic and Cultural District On the Design of the Three-Camp Land Parcel in Laomendong, Nanjing. Archit. J. 2017, 4, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mano, Y.; Takeda, Y.; Kobayashi, A.; Satoh, S. The Relationship between urban renewal, housing supply and housing relocation in Ichitera-Kototoi area, Sumida ward-Cooperation between housing environment improvement and housing support program in the build-up area densely crowded with wooden buildings. City Plan. Rev. 2003, 38, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).