A Critical Realist Approach to Reflexivity in Sustainability Research

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Data Collection Methods

3. Reflexivity in Sustainability Science

3.1. Reflexivity in the Process of Knowledge (co-) Production

3.2. Barriers to the Emergence of Reflexivity

3.3. Enabling Factors for Reflexivity

3.4. Knowledge Gaps in Understanding Reflexivity

4. An Alternative View on Reflexivity

4.1. A Critical Realist Perspective, Why?

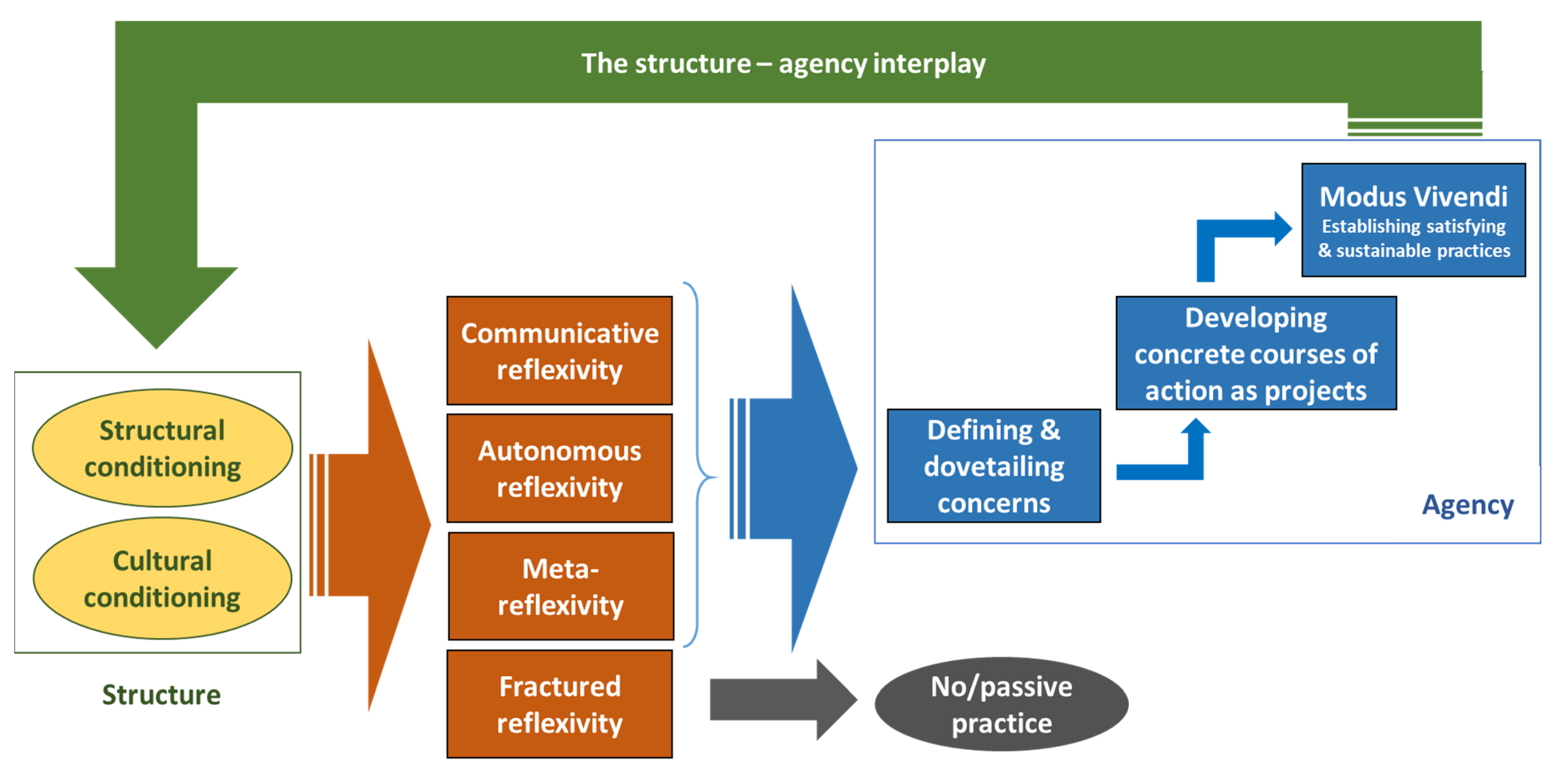

4.2. Taking Archer’s Framework on Reflexivity into Sustainability Research

4.3. Materially Grounded Factors Affecting Reflexivity

4.4. Culturally Grounded Factors Affecting Reflexivity

5. Towards the Emergence of Meta-Reflexivity in Sustainability Science

6. Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clark, W.C.; Harley, A.G. Sustainability science: Toward a synthesis. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2020, 45, 331–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaggård, Å.; Ness, B.; Harnesk, D. Finding an academic space: Reflexivity among sustainability researchers. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, G.; Dagli, W.; Hambly Odame, H. Co-production of knowledge for sustainability: An application of reflective practice in doctoral studies. Reflective Pract. 2020, 21, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.J.; Wiek, A.; Bergmann, M.; Stauffacher, M.; Martens, P.; Moll, P.; Swilling, M.; Thomas, C.J. Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmayer, J.M.; Schäpke, N. Action, research and participation: Roles of researchers in sustainability transitions. Sustain. Sci. 2014, 9, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, F.; Guillermin, M.; Dedeurwaerdere, T. A pragmatist approach to transdisciplinarity in sustainability research: From complex systems theory to reflexive science. Futures 2015, 65, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, W.C.; Van Kerkhoff, L.; Lebel, L.; Gallopin, G.C. Crafting usable knowledge for sustainable development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4570–4578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, S.; Aalbers, R.; Sengoku, S. Effects and Interactions of Researcher’s Motivation and Personality in Promoting Interdisciplinary and Transdisciplinary Research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastar, M.; Boda, C.; Olsson, L. A critical realist inquiry in conducting interdisciplinary research: An analysis of LUCID examples. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- John, B.; Luederitz, C.; Lang, D.J.; von Wehrden, H. Toward sustainable urban metabolisms. Syst. Underst. Syst. Transform. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 157, 402–414. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, D.J.; Wiek, A.; von Wehrden, H. Bridging divides in sustainability science. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazey, I.; Schäpke, N.; Caniglia, G.; Patterson, J.; Hultman, J.; van Mierlo, B.; Säwe, F.; Wiek, A.; Wittmayer, J.; Aldunce, P.; et al. Ten essentials for action-oriented and second order energy transitions, transformations and climate change research. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 40, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffa, R.K.; Riechers, M.; Martín-López, B. Correction to: A feminist ethos for caring knowledge production in transdisciplinary sustainability science. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilisa, B. Decolonising transdisciplinary research approaches: An African perspective for enhancing knowledge integration in sustainability science. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 813–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, S.; Kirchberg, V. Music and sustainability: Organizational cultures towards creative resilience—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1487–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, H.; Nordén, B. Working with the divides: Two critical axes in development for transformative professional practices. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2017, 18, 666–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A. Deconstructing a 2-year long transdisciplinary sustainability project in Northern universities: Is rhetorical nobility obscuring procedural and political discords? Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 1111–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellberg, M.M.; Cockburn, J.; Holden, P.B.; Lam, D.P.M. Towards a caring transdisciplinary research practice: Navigating science, society and self. Ecosyst. People 2021, 17, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polk, M. Transdisciplinary co-production: Designing and testing a transdisciplinary research framework for societal problem solving. Futures 2015, 65, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaziulusoy, A.I.; Ryan, C.; McGrail, S.; Chandler, P.; Twomey, P. Identifying and addressing challenges faced by transdisciplinary research teams in climate change research. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 123, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, A.; Schäfer, M.; Bergmann, M.; Jahn, T.; Marg, O.; Nagy, E.; Ransiek, A.C.; Theiler, L. Societal effects of transdisciplinary sustainability research—How can they be strengthened during the research process? Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 101, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthe, T. Success in transdisciplinary sustainability research. Sustainability 2017, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felt, U.; Igelsböck, J.; Schikowitz, A.; Völker, T. Transdisciplinary Sustainability Research in Practice: Between Imaginaries of Collective Experimentation and Entrenched Academic Value Orders. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2016, 41, 732–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreavy, B.; Ranco, D.; Daigle, J.; Greenlaw, S.; Altvater, N.; Quiring, T.; Michelle, N.; Paul, J.; Binette, M.; Benson, B.; et al. Science in Indigenous homelands: Addressing power and justice in sustainability science from/with/in the Penobscot River. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Yanez, G.; House-Peters, L.; Garcia-Cartagena, M.; Bonelli, S.; Lorenzo-Arana, I.; Ohira, M. Mobilizing transdisciplinary collaborations: Collective reflections on decentering academia in knowledge production. Glob. Sustain. 2019, 2, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojórquez-Tapia, L.A.; Eakin, H.; Hernández-Aguilar, B.; Shelton, R. Addressing complex, political and intransient sustainability challenges of transdisciplinarity: The case of the MEGADAPT project in Mexico City. Environ. Dev. 2021, 38, 100604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosendahl, J.; Zanella, M.A.; Rist, S.; Weigelt, J. Scientists’ situated knowledge: Strong objectivity in transdisciplinarity. Futures 2015, 65, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, M.G.; Cockburn, J.J.; De Wet, C.; Bezerra, J.C.; Weaver, M.J.T.; Finca, A.; De Vos, A.; Ralekhetla, M.M.; Libala, N.; Mkabile, Q.B.; et al. Exploring and expanding transdisciplinary research for sustainable and just natural resource management. Ecol. Soc. 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osinski, A. Towards a critical sustainability science? Participation of disadvantaged actors and power relations in transdisciplinary research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, L.; de Jong, S.; Brouwer, S. Collaboration between Heterogeneous Practitioners in Sustainability Research: A Comparative Analysis of Three Transdisciplinary Programmes. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bulten, E.; Hessels, L.K.; Hordijk, M.; Segrave, A.J. Conflicting roles of researchers in sustainability transitions: Balancing action and reflection. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1269–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreavy, B.; Lindenfeld, L.; Bieluch, K.H.; Silka, L.; Leahy, J.; Zoellick, B. Communication and sustainability science teams as complex systems. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.; Michelsen, G. Learning for change: An educational contribution to sustainability science. Sustain. Sci. 2013, 8, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.; van Kerkhoff, L.; Wagenaar, H. Beyond “linking knowledge and action”: Towards a practice-based approach to transdisciplinary sustainability interventions. Policy Stud. 2019, 40, 534–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, H.; Goggins, G.; Fahy, F. From invisibility to impact: Recognising the scientific and societal relevance of interdisciplinary sustainability research. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, C.D.; Even, T.L.; Frame, S.M. Merging the arts and sciences for collaborative sustainability action: A methodological framework. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 1067–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disterheft, A.; Pijetlovic, D.; Müller-Christ, G. On the road of discovery with systemic exploratory constellations: Potentials of online constellation exercises about sustainability transitions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, F.; Kørnøv, L. Art and higher education for environmental sustainability: A matter of emergence? Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2022, 23, 728–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras, M.; Galafassi, D.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Ravera, F.; Berraquero-Díaz, L.; Ruiz-Mallén, I. Realising potentials for arts-based sustainability science. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1875–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M.G.; Williams, S.; Nanz, P.; Renn, O. Characteristics, potentials, and challenges of transdisciplinary research. One Earth 2022, 5, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, Y.; Jerneck, A.; Kronsell, A.; Steen, K. At the nexus of problem-solving and critical research. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockburn, J. Knowledge integration in transdisciplinary sustainability science: Tools from applied critical realism. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callinicos, A. Making History: Agency, Structure, and Change in Social Theory; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Marguin, S.; Haus, J.; Heinrich, A.J.; Kahl, A.; Schendzielorz, C.; Singh, A. Positionality Reloaded: Debating the Dimensions of Reflexivity in the Relationship Between Science and Society: An Editorial. Hist. Soc. Res.-Hist. Soz. 2021, 46, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, M.S. The Reflexive Imperative in Late Modernity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, M.; Bhaskar, R.; Collier, A.; Lawson, T.; Norrie, A. Critical Realism: Essential Readings; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, M.S. Making Our Way through the World: Human Reflexivity and Social Mobility; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, M.S. Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. Causality and explanation in socio-technical transitions research: Mobilising epistemological insights from the wider social sciences. Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buch-Hansen, H.; Nesterova, I. Towards a science of deep transformations: Initiating a dialogue between degrowth and critical realism. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 190, 107188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, R.; Frank, C.; Høyer, K.G.; Parker, J.; Naess, P. Interdisciplinarity and Climate Change: Transforming Knowledge and Practice for Our Global Future; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Donati, P.; Archer, M.S. The Relational Subject; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. Unpacking the black box of a mature student’s processes of social engagement: Focusing on reflexivity, structure and agency. Camb. J. Educ. 2021, 51, 785–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyke, M.; Johnston, B.; Fuller, A. Approaches to reflexivity: Navigating educational and career pathways. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2012, 33, 831–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golob, T.; Makarovič, M. Reflexivity and structural positions: The effects of generation, gender and education. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, D.J.; Stedman, R.C. Calling forth the change-makers:Reflexivity theory and climate change attitudes and behaviors. Acta Sociol. 2018, 61, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, A. Coping With Life: A Typology of Personal Reflexivity. Sociol. Q. 2017, 58, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. New managerialism, neoliberalism and ranking. Ethics Sci. Environ. Politics 2014, 13, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessant, S.E.; Robinson, Z.P.; Ormerod, R.M. Neoliberalism, new public management and the sustainable development agenda of higher education: History, contradictions and synergies. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 21, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, B. The neoliberal academic: Illustrating shifting academic norms in an age of hyper-performativity. Educ. Philos. Theory 2021, 53, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrifield, A. The Amateur: The Pleasures of Doing What You Love; Verso Books: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Oleksiyenko, A. Zones of alienation in global higher education: Corporate abuse and leadership failures. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2018, 24, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessant, S.E.; Robinson, Z.P. Rating and rewarding higher education for sustainable development research within the marketised higher education context: Experiences from English universities. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 548–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kates, R.W.; Clark, W.C.; Corell, R.; Hall, J.M.; Jaeger, C.C.; Lowe, I.; McCarthy, J.J.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; Bolin, B.; Dickson, N.M.; et al. Sustainability Science. Science 2001, 292, 641–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagatsu, M.; Davis, T.; DesRoches, C.T.; Koskinen, I.; MacLeod, M.; Stojanovic, M.; Thorén, H. Philosophy of science for sustainability science. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 1807–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniglia, G.; Luederitz, C.; von Wirth, T.; Fazey, I.; Martin-López, B.; Hondrila, K.; König, A.; von Wehrden, H.; Schäpke, N.; Laubichler, M. A pluralistic and integrated approach to action-oriented knowledge for sustainability. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnhout, E.; Metze, T.; Wyborn, C.; Klenk, N.; Louder, E. The politics of co-production: Participation, power, and transformation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 42, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyborn, C.; Datta, A.; Montana, J.; Ryan, M.; Leith, P.; Chaffin, B.; Miller, C.; Van Kerkhoff, L. Co-producing sustainability: Reordering the governance of science, policy, and practice. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2019, 44, 319–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, W.C. Sustainability Science: A room of its own. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 1737–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, L. Critical Realist versus Mainstream Interdisciplinarity. J. Crit. Realism 2014, 13, 52–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallis, G.; Kostakis, V.; Lange, S.; Muraca, B.; Paulson, S.; Schmelzer, M. Research On Degrowth. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2018, 43, 291–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Aguilera, J.N.; Anderson, W.; Bridges, A.L.; Fernandez, M.P.; Hansen, W.D.; Maurer, M.L.; Ilboudo Nébié, E.K.; Stock, A. Supporting interdisciplinary careers for sustainability. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 374–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, B. Collegiality and performativity in a competitive academic culture. High. Educ. Rev. 2016, 48, 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Scoles, J.; Huxham, M.; Sinclair, K.; Lewis, C.; Jung, J.; Dougall, E. The other side of a magic mirror: Exploring collegiality in student and staff partnership work. Teach. High. Educ. 2021, 26, 712–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godber, K.A.; Atkins, D.R. COVID-19 Impacts on Teaching and Learning: A Collaborative Autoethnography by Two Higher Education Lecturers. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 647524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbäck, E.; Hakonen, M.; Tienari, J. Academic identities and sense of place: A collaborative autoethnography in the neoliberal university. Manag. Learn. 2022, 53, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, R.; Danermark, B.; Price, L. Interdisciplinarity and Wellbeing: A Critical Realist General Theory of Interdisciplinarity; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bergland, B. The incompatibility of neoliberal university structures and interdisciplinary knowledge: A feminist slow scholarship critique. Educ. Philos. Theory 2018, 50, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountz, A.; Bonds, A.; Mansfield, B.; Loyd, J.; Hyndman, J.; Walton-Roberts, M.; Basu, R.; Whitson, R.; Hawkins, R.; Hamilton, T. For slow scholarship: A feminist politics of resistance through collective action in the neoliberal university. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geogr. 2015, 14, 1235–1259. [Google Scholar]

- Care, O.; Bernstein, M.J.; Chapman, M.; Diaz Reviriego, I.; Dressler, G.; Felipe-Lucia, M.R.; Friis, C.; Graham, S.; Hänke, H.; Haider, L.J.; et al. Creating leadership collectives for sustainability transformations. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Porta, D.; Cini, L. Contesting Higher Education: Student Movements against Neoliberal Universities; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nastar, M. A Critical Realist Approach to Reflexivity in Sustainability Research. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2685. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032685

Nastar M. A Critical Realist Approach to Reflexivity in Sustainability Research. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2685. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032685

Chicago/Turabian StyleNastar, Maryam. 2023. "A Critical Realist Approach to Reflexivity in Sustainability Research" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2685. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032685

APA StyleNastar, M. (2023). A Critical Realist Approach to Reflexivity in Sustainability Research. Sustainability, 15(3), 2685. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032685