Measuring and Evaluating the Commodification of Sustainable Rural Living Areas in Zhejiang, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

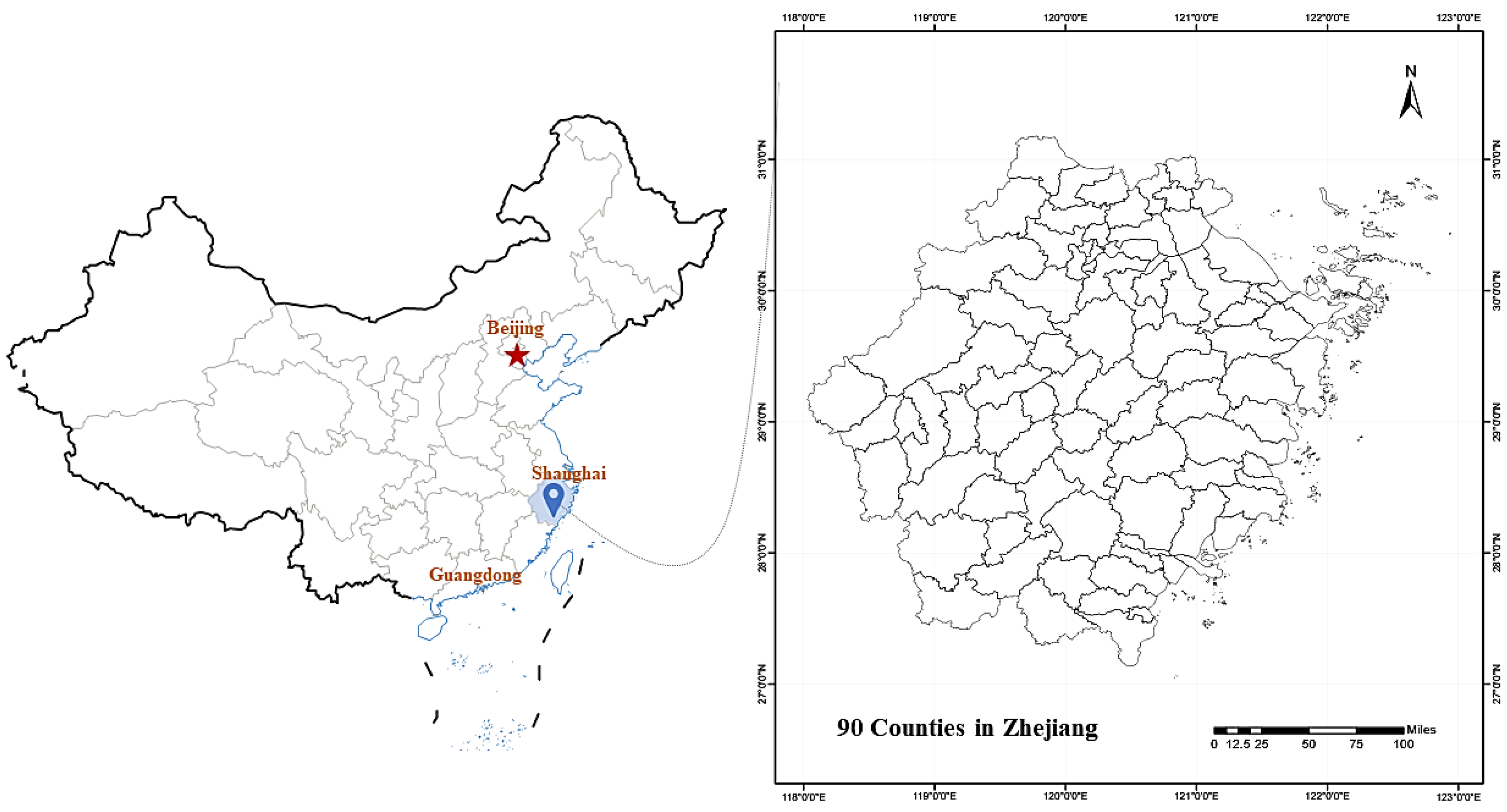

3.1. Research Target Area

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Construction of Evaluation Index System

3.4. Evaluation Approach of Rural Space Commodification Level

3.4.1. Determination of the Index Weights

- Forming a matrix. According to the basic idea of the overall entropy method, the 3D data table is sorted into a 2D table in time order. Taking the cultural heritage and industrial integration system as an example, it is necessary to evaluate the current situation of the cultural and tourism integration level of 90 counties with 6 indicators. Thus, a 90 × 6-order matrix can be obtained.

- Data standardization and dimensionless. In order to eliminate the influence of magnitude and dimensions, the raw data need to be standardized. In this study, all indicators are positive indicators. Thus, non-negative translation was not to be carried out, and then the dimensionless method was adopted to ensure that all normalized data are positive and can be calculated. The calculation formulas are as follows:where the “m” indicators are selected for a total of “n” samples, then is the value of the “j” indicator of the “I” sample, i = 1,2,3...n; j = 1,2,3...m. is the minimum index of column j; is the maximum index of column j. In order to ensure that the logarithm calculation is meaningful, 0.01 is added.

- Calculate the proportion of the j-th indicator of the i-th:

- 2.

- Calculation of the information entropy:where K is a constant, and K > 0.

- 3.

- Calculate the information utility value of the j-th indicator:

- 4.

- Calculate the weights of the indicators:

3.4.2. Calculation of the Comprehensive Evaluation Score of the Degree of the Commodification of Each County, for Which the Equation Is:

4. Result

4.1. Analysis of the County Differences in the Commodification Evaluation System

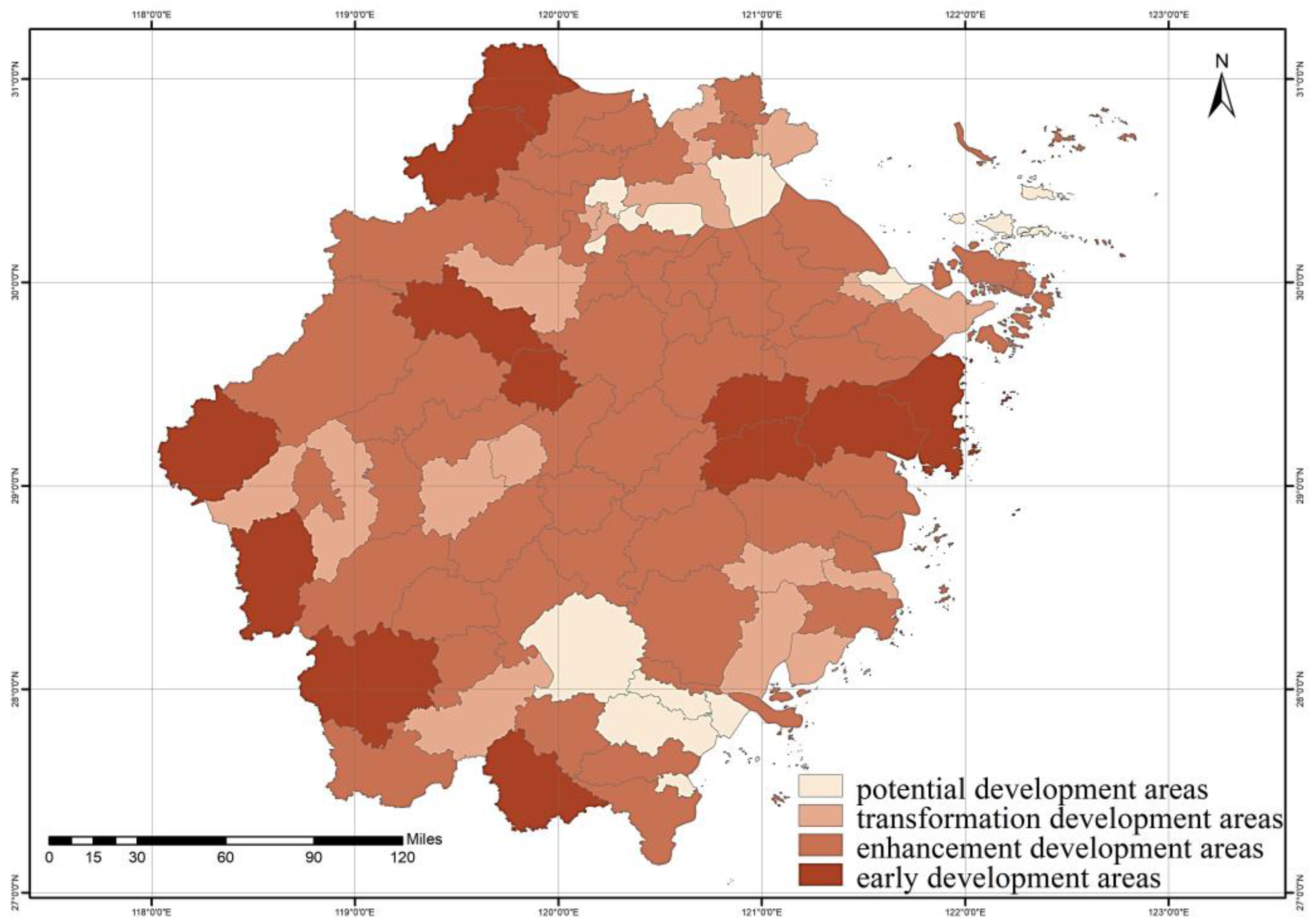

4.2. Analysis of the Different Types of the Commodification Development Potential

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Contributions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, T.; Long, H.; Liu, Y.; Tu, S. Multi-Scale Analysis of Rural Housing Land Transition under China’s Rapid Urbanization: The Case of Bohai Rim. Habitat Int. 2015, 48, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.X.; Li, Z. Rural-to-Urban Migration in China. Asian-Pac. Econ. Lit. 1996, 10, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalina, P.D.; Dupre, K.; Wang, Y. Rural Tourism: A Systematic Literature Review on Definitions and Challenges. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B.; Wornell, R.; Youell, R. Re-Conceptualising Rural Resources as Countryside Capital: The Case of Rural Tourism. J. Rural Stud. 2006, 22, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohe, Y. Evaluating Diversified Utilization of Rural Resources: A Case of Rural Tourism. J. Rural Probl. 2008, 43, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.E.; Yin, J.; Xu, S.-Y. A Study on the Quantitative Evaluation of Rural Tourism Resources in Shanghai. Tour. Trib. 2007, 8, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva-Álvaro, J.-J.; Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.; Sáez-Martínez, F.-J. Rural Tourism: Development, Management and Sustainability in Rural Establishments. Sustainability 2017, 9, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Kong, X. Tourism-Led Commodification of Place and Rural Transformation Development: A Case Study of Xixinan Village, Huangshan, China. Land 2021, 10, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonts, M.; Greive, S. Commodification and Creative Destruction in the Australian Rural Landscape: The Case of Bridgetown, Western Australia. Aust. Geogr. Stud. 2002, 40, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, M.; Jongerden, J.; Hilton, A. Commodification and the Social Commons: Smallholder Autonomy and Rural–Urban Kinship Communalism in Turkey. Agrar. South J. Political Econ. Triannual J. Agrar. South Netw. CARES 2014, 3, 337–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokpelnis, K.; Ho, P.; Cheng, G.; Zhao, H. Consumer Perceptions of the Commodification and Related Conservation of Traditional Indigenous Naxi Forest Products as Credence Goods (China). Sustainability 2018, 10, 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Wang, H.; Huang, A.; Xu, Y.; Lu, L.; Ji, Z. Identification and Spatial-Temporal Evolution of Rural “Production-Living-Ecological” Space from the Perspective of Villagers’ Behavior—A Case Study of Ertai Town, Zhangjiakou City. Land Use Policy 2021, 106, 105457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, G.; He, P.; Gao, X.; Lin, Z.; Huang, C.; Zhou, W.; Deng, O.; Xu, C.; Deng, L. Land Use Optimization of Rural Production–Living–Ecological Space at Different Scales Based on the BP–ANN and CLUE–S Models. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 137, 108710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; ISBN 978-0-631-18177-4. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, M.; Flemmen, A.B.; Wollan, G. Beyond the Idyll: Contested Spaces of Rural Tourism. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr.—Nor. J. Geogr. 2014, 68, 202–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M.; Woods, M. Rural Geography: Processes, Responses and Experiences in Rural Restructuring. Rural Geogr. Process. Responses Exp. Rural Restruct. 2005, 7, 494–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, H.C. Commodification: Re-Resourcing Rural Areas. In Handbook of Rural Studies; Sage Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akira, T. Regional Development Owing to the Commodification of Rural Spaces in Japan. Geogr. Rev. Jpn. Ser. B 2010, 82, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloke, P. The Countryside as Commodity: New Spaces for Rural Leisure. In Leisure and the Environment; Bellhaven: London, UK, 1993; pp. 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, C.; Li, G.B. Suburban Rural Space Reconstruction from Perspective of Rescaling: The Case of Yaogang Village in Changzhou. Mod. Urban Res. 2018, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, D.; Long, H. Rural Spatial Governance and Urban-Rural Integration Development. Li Xue Bao Chung-Kuo Ti Li Hsüeh Hui Pien Chi 2020, 75, 1272–1286. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.X.; Tang, D.J. Spatial Pattern of Rural Flow in Zhejiang and Its Influencing Factors: Based on the Analysis of Taobao Village and Tourism Village. Acta Agric. Zhejiangensis 2016, 28, 1438–1446. [Google Scholar]

- Gotham, K.F. Marketing Mardi Gras: Commodification, Spectacle and the Political Economy of Tourism in New Orleans. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 1735–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Wang, P.; Wang, C.; Fan, Y. Commodification of Rural Spaces and Rural Restructuring and Their Future Research Directions in China. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2019, 39, 316–324. [Google Scholar]

- Shuang, G. Commodification of Place, Consumption of Identity: The Sociolinguistic Construction of a ‘Global Village’ in Rural China. J. Socioling. 2012, 16, 336–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani Fazli, A.; Sajjadi, Z.; Sedighi, S. Analyses of Effective Factors on Intensifying of Tourism Space Commodification Process (Case Study: Rural Areas of Ahmoudabad Town). Tour. Manag. Stud. 2019, 14, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordel, S. Selling Ruralities: How Tourist Entrepreneurs Commodify Traditional and Alternative Ways of Conceiving the Countryside. Rural Soc. 2016, 25, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Yan, L.; Zeng, J.; Zhu, Y. Progress and Prospect on Rural Living Space. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2017, 37, 375–385. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, M.; Shen, J. State-Led Commodification of Rural China and the Sustainable Provision of Public Goods in Question: A Case Study of Tangjiajia, Nanjing. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 93, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G. The Development of Indicators for Sustainable Tourism: Results of a Delphi Survey of Tourism Researchers. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Ma, X.; Gao, Y.; Johnson, L. The Lost Countryside: Spatial Production of Rural Culture in Tangwan Village in Shanghai. Habitat Int. 2020, 98, 102137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- René, V.D.D.; Ren, C.B.; Jóhannesson, G. Actor-Network Theory and Tourism: Ordering, Materiality and Multiplicity; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Johannesson, G.T. Tourism Translations: Actor-Network Theory and Tourism Research. Tour. Stud. 2005, 5, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ji, M.; Zhang, Y. Tourism Sustainability in Tibet—Forward Planning Using a Systems Approach. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 56, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, J. Signs of the Post-rural: Marketing Myths of a Symbolic Countryside. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 1998, 80, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, J.; Ojeda, D. Violence and Dispossession in Tourism Development: A Critical Geographical Approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneafsey, M. Tourism, Place Identities and Social Relations in the European Rural Periphery. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2000, 7, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, D.J. Rural Tourism: A Case of Lifestyle-Led Opportunities. Aust. Geogr. 2003, 34, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardone, E.; Rattus, K.; Jääts, L. Creative Commodification of Rural Life from a Performance Perspective: A Study of Two South-East Estonian Farm Tourism Enterprises. J. Balt. Stud. 2013, 44, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J. Statistical Research on the Development of Rural Tourism Economy Industry under the Background of Big Data. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2021, 2021, 9152173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederholm, E.A. Being with Others: The Commodification of Relationships in Tourism. In Proceedings of the Gazing, Glancing, Glimpsing: Tourists and Tourism in a Visual World, Brighton, UK, 13–15 June 2007. The Association for Tourism and Leisure Education and Research (ATLAS). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, F.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, J.; Nie, R. Research on the Rural Homestay Inn Development under the View of Rural Revitalization: A Case of “Ten Thousand Hostels” in Zengcheng District, Guangzhou City. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2019, 27, 218–226. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhong, H.; Jian, Y.; Shi, L. Multi-Dimension Evaluation of Rural Development Degree and Its Uncertainties: A Comparison Analysis Based on Three Different Weighting Assignment Methods. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 130, 108096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Yun, Y.; Sun, J. Entropy Method for Determination of Weight of Evaluating Indicators in Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation for Water Quality Assessment. J. Environ. Sci. 2006, 18, 1020–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.-F.; Liu, Q.; Peng, X.-X. Evaluation and Analysis of Regional Innovation Ability in China Based on Overall Entropy Method. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2015, 24, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blancas, F.J.; Lozano-Oyola, M.; González, M.; Guerrero, F.M.; Caballero, R. How to Use Sustainability Indicators for Tourism Planning: The Case of Rural Tourism in Andalusia (Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 412, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, C.; Liu, Z.; Yang, L.; Wang, L. Evaluation of Spatial Reconstruction and Driving Factors of Tourism-Based Countryside. Land 2022, 11, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keisuke, M. Commodification of a Rural Space in a World Heritage Registration Movement: Case Study of Nagasaki Church Group. Geogr. Rev. Jpn. Ser. B 2010, 82, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Object | System | Indicator | Characteristics of Indicators | Comprehensive Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhejiang County Living Space Commodification Evaluation (A) | Cultural heritage and industrial integration (B1) | National historical and cultural villages (C1) | + | 0.0581 |

| Provincial historical and cultural villages (C2) | + | 0.0377 | ||

| History education bases (C3) | + | 0.0680 | ||

| Provincial rural tourism industry cluster (C4) | + | 0.0930 | ||

| Provincial primary and secondary school study and practice education bases (C5) | + | 0.0297 | ||

| Cultural tourism integration pilot areas (C6) | + | 0.0653 | ||

| Scenic area protection and scientific governance (B2) | 3A-level scenic villages (C7) | + | 0.0103 | |

| 5A-level scenic towns (C8) | + | 0.1376 | ||

| 4A-level scenic towns (C9) | + | 0.0985 | ||

| Scenery towns (C10) | + | 0.0180 | ||

| Tourism development and urban and rural construction (B3) | National rural tourism demonstration villages (C11) | + | 0.0483 | |

| Provincial rural tourism demonstration village (C12) | + | 0.0125 | ||

| National all-for-one tourism demonstration areas (C13) | + | 0.1231 | ||

| Provincial all-for-one tourism demonstration areas (C14) | + | 0.0261 | ||

| National tourism resorts (C15) | + | 0.1376 | ||

| Provincial tourism resorts (C16) | + | 0.0361 |

| Rank | Areas | Score | Rank | Areas | Score | Rank | Areas | Score | Rank | Areas | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ninghai | 0.6077 | 11 | Jiangshan | 0.3189 | 21 | Pingyang | 0.2314 | 31 | Taishun | 0.1762 |

| 2 | Anji | 0.5673 | 12 | Kaihua | 0.3180 | 22 | Xiangshan | 0.2251 | 32 | Lucheng | 0.1759 |

| 3 | Yuhang | 0.3819 | 13 | Yiwu | 0.3018 | 23 | Suichang | 0.2250 | 33 | Xihu | 0.1737 |

| 4 | Tonglu | 0.3616 | 14 | Cangnan | 0.2973 | 24 | Yingzhou | 0.2225 | 34 | Pujiang | 0.1723 |

| 5 | Xianju | 0.3436 | 15 | Changxing | 0.2971 | 25 | Zhuji | 0.2213 | 35 | Nanhu | 0.1693 |

| 6 | Deqing | 0.3434 | 16 | Songyang | 0.2967 | 26 | Longyou | 0.2200 | 36 | Shengsi | 0.1692 |

| 7 | Longquan | 0.3424 | 17 | Chunan | 0.2697 | 27 | Wuxing | 0.2189 | 37 | Putuo | 0.1644 |

| 8 | Tiantai | 0.3375 | 18 | Tongxiang | 0.2666 | 28 | Panan | 0.2164 | 38 | Jinyun | 0.1517 |

| 9 | Xinchang | 0.3256 | 19 | Jiashan | 0.2635 | 29 | Xiashan | 0.2032 | 39 | Yongjia | 0.1438 |

| 10 | Jiande | 0.3237 | 20 | Keqiao | 0.2558 | 30 | Nanxun | 0.1914 | 40 | Kecheng | 0.1424 |

| Types of the Commodification Development Potential in Rural Living Space | Main Classification Basis | Current Characteristics | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early development areas | C(H)-S(H)-T(H) 1 | These areas have a good natural environment, excellent transportation location, good road accessibility and diversity of transportation modes, and diversified development of rural industries. | 12 |

| Enhancement development areas | C(M)-S(M)-T(M), C(H)-S(M)-T(M), C(M)-S(M)-T(L), C(M)-S(H)-T(M), C(M)-S(L)-T(M), C(L)-S(H)-T(M) | These areas have a good natural environment, excellent transportation location, good road accessibility and diversity of transportation modes, and diversified development of rural industries. | 50 |

| Transformation development areas | C(L)-S(L)-T(M), C(M)-S(L)-T(L), C(L)-S(M)-T(L), C(L)-S(L)-T(H), C(H)-S(L)-T(L), C(L)-S(H)-T(L) | These areas have small rural living spaces, some of which are mainly urban areas, with relatively poor environmental quality due to historical industrial structure, and lack of effective governance and management. | 17 |

| Potential development areas | C(L)-S(L)-T(L) | The overall level of the commodification of rural living space in these areas is low. Some of them are areas with high local economic levels and a high degree of commodification, while others have rural tourism resources due to their poor location conditions and lack of accessibility and still have potential in the development of rural living space commodification. | 11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, C.; Zheng, G. Measuring and Evaluating the Commodification of Sustainable Rural Living Areas in Zhejiang, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043349

Wei C, Zheng G. Measuring and Evaluating the Commodification of Sustainable Rural Living Areas in Zhejiang, China. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043349

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Chen, and Guoquan Zheng. 2023. "Measuring and Evaluating the Commodification of Sustainable Rural Living Areas in Zhejiang, China" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043349

APA StyleWei, C., & Zheng, G. (2023). Measuring and Evaluating the Commodification of Sustainable Rural Living Areas in Zhejiang, China. Sustainability, 15(4), 3349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043349