Medicine Students’ Opinions Post-COVID-19 Regarding Online Learning in Association with Their Preferences as Internet Consumers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Favourable Opinions About Online Learning: | |

| Item 1a | I am satisfied with the online didactic activities I attended so far. |

| Item 2a | I prefer to learn using digital tool and resources. |

| Item 3a | I prefer to work autonomously. |

| Item 4a | The online didactic activities are more efficient than classical ones. |

| Item 5a | The online didactic activities focus on the quality of the transmitted materials. |

| Item 6a | The online didactic activities are better in communicating the essence of materials than the classical ones. |

| Item 7a | The online didactic activities make me understand faster and easier the presented concepts. |

| Item 8a | The online didactic activities make me be more productive as a student. |

| Item 9a | The online didactic activities are more comfortable because I don’t need to go to the faculty. |

| Item 10a | The online didactic activities are flexible because I can learn when I want to. |

| Item 11a | The online lectures are more useful for me than the classical ones. |

| Item 12a | The practical online activities (seminars, laboratories) are more useful for me than the classical ones. |

| Item 13a | The teachers work more during online didactic activities than during classical ones. |

| Item 14a | The students are asked to solve more homework and tasks during online didactic activities than during the classical ones. |

| Item 15a | The tasks are clearer and easier to solve during online didactic activities than during classical ones. |

| Item 16a | I have the option to customize the tasks to solve, according to my own learning pace. |

| Item 17a | The digital competencies acquired through online learning will be useful in my future didactic and professional activities. |

| Not favourable opinions about online learning: I do not prefer to participate in online didactic activities because of the following reasons: | |

| Item 1b | The poor level of my digital competencies |

| Item 2b | Technical difficulties (platforms to install, browsers, accounts) |

| Item 3b | Rigid and not flexible tools |

| Item 4b | Limited access to the Internet |

| Item 5b | I don’t have a computer with the required technical features |

| Item 6b | I don’t have the time necessary to understand and use adequately the digital tools and resources |

| Item 7b | I don’t find a proper motivation |

| Item 8b | I don’t have the habit to learn using these technologies |

| Item 9b | Lack of teachers’ control and constant monitoring of my activities |

| Item 10b | Lack of direct communication and human interaction with teachers |

| Item 11b | Lack of an efficient structure of the content taught by the teaching staff |

| Item 12b | Lack of focused and relevant feedback from teachers |

| Item 13b | Lack of a well-structured schedule for didactic activities |

| Item 14b | Limitations due to the particularities of some disciplines (in case of my study objects, the learning activities cannot be easily transferred to the online environment) |

| General opinion about using multimedia resources in the learning process: | |

| Item 1c | I prefer to learn using multimedia tools and resources. |

| General preferences as Internet users: | |

| Item 2c | I use the internet mainly for information |

| Item 3c | I use the internet mainly for communication |

| Item 4c | I use the internet mainly for entertainment |

| Item 5c | I use the internet mainly for domestic facilities |

| Recorded Answers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—Total Disagreement n (%) | 2—Partial Disagreement n (%) | 3—Neutral n (%) | 4—Partial Agreement n (%) | 5—Total Agreement n (%) | |

| Favourable opinions about online learning: | |||||

| Item 1a | 18 (3.3) | 78 (14.2) | 258 (46.8) | 147 (26.7) | 50 (9.1) |

| Item 2a | 17 (3.1) | 77 (14) | 196 (35.6) | 165 (29.9) | 96 (17.4) |

| Item 3a | 6 (1.1) | 59 (10.7) | 229 (41.6) | 175 (31.8) | 82 (14.9) |

| Item 4a | 135 (24.5) | 190 (34.5) | 156 (28.3) | 51 (9.3) | 19 (3.4) |

| Item 5a | 26 (4.7) | 80 (14.5) | 208 (37.7) | 165 (29.9) | 72 (13.1) |

| Item 6a | 140 (25.4) | 178 (32.3) | 153 (27.8) | 55 (10) | 25 (4.5) |

| Item 7a | 138 (25) | 175 (31.8) | 166 (30.1) | 44 (8) | 28 (5.1) |

| Item 8a | 135 (24.5) | 163 (29.6) | 154 (27.9) | 61 (11.1) | 38 (6.9) |

| Item 9a | 11 (2) | 36 (6.5) | 90 (16.3) | 185 (33.6) | 229 (41.6) |

| Item 10a | 16 (2.9) | 49 (8.9) | 155 (28.1) | 196 (35.6) | 135 (24.5) |

| Item 11a | 98 (17.8) | 120 (21.8) | 174 (31.6) | 83 (15.1) | 76 (13.8) |

| Item 12a | 237 (43) | 169 (30.7) | 103 (18.7) | 19 (3.4) | 23 (4.2) |

| Item 13a | 77 (14) | 120 (21.8) | 230 (41.7) | 91 (16.5) | 33 (6) |

| Item 14a | 69 (12.5) | 182 (33) | 220 (39.9) | 54 (9.8) | 26 (4.7) |

| Item 15a | 75 (13.6) | 176 (31.9) | 228 (41.4) | 48 (8.7) | 24 (4.4) |

| Item 16a | 29 (5.3) | 52 (9.4) | 203 (36.8) | 183 (33.2) | 84 (15.2) |

| Item 17a | 41 (7.4) | 115 (20.9) | 184 (33.4) | 139 (25.2) | 72 (13.1) |

| Not favourable opinions about online learning: | |||||

| Item 1b | 327 (59.3) | 111 (20.1) | 80 (14.5) | 26 (4.7) | 7 (1.3) |

| Item 2b | 189 (34.3) | 141 (25.6) | 120 (21.8) | 75 (13.6) | 26 (4.7) |

| Item 3b | 204 (37) | 145 (26.3) | 122 (22.1) | 64 (11.6) | 16 (2.9) |

| Item 4b | 315 (57.2) | 114 (20.7) | 71 (12.9) | 40 (7.3) | 11 (2) |

| Item 5b | 340 (61.7) | 104 (18.9) | 55 (10) | 37 (6.7) | 15 (2.7) |

| Item 6b | 294 (53.4) | 120 (21.8) | 93 (16.9) | 37 (6.7) | 7 (1.3) |

| Item 7b | 139 (25.2) | 100 (18.1) | 133 (24.1) | 94 (17.1) | 85 (15.4) |

| Item 8b | 180 (32.7) | 106 (19.2) | 131 (23.8) | 90 (16.3) | 44 (8) |

| Item 9b | 171 (31) | 138 (25) | 140 (25.4) | 73 (13.2) | 29 (5.3) |

| Item 10b | 90 (16.3) | 63 (11.4) | 105 (19.1) | 142 (25.8) | 151 (27.4) |

| Item 11b | 118 (21.4) | 146 (26.5) | 157 (28.5) | 78 (14.2) | 52 (9.4) |

| Item 12b | 130 (23.6) | 120 (21.8) | 139 (25.2) | 93 (16.9) | 69 (12.5) |

| Item 13b | 171 (31) | 136 (24.7) | 123 (22.3) | 58 (10.5) | 63 (11.4) |

| Item 14b | 101 (18.3) | 69 (12.5) | 125 (22.7) | 111 (20.1) | 145 (26.3) |

| Recorded Answers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—Very Low n (%) | 2— Low n (%) | 3— Average n (%) | 4— High n (%) | 5—Very High n (%) | |

| To what extent have you participated in the online lectures /seminars /labs of your study program? | 4 (0.7) | 12 (2.2) | 71 (12.9) | 170 (30.9) | 294 (53.4) |

| To what extent have you had active interventions during the online lectures /seminars /labs of your study program? | 49 (8.9) | 120 (21.8) | 216 (39.2) | 120 (21.8) | 46 (8.3) |

| To what extent would you prefer to participate in online lectures in the future? | 81 (14.7) | 58 (10.5) | 170 (30.9) | 144 (26.1) | 98 (17.8) |

| To what extent would you prefer to participate in online seminars /labs in the future? | 174 (31.6) | 112 (20.3) | 135 (24.5) | 67 (12.2) | 63 (11.4) |

| n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Opinion about using multimedia resources in learning process: | ||

| 1—total disagreement | 20 (3.6) | |

| 2—partial disagreement | 83 (15.1) | |

| 3—neutral | 221 (40.1) | |

| 4—partial agreement | 116 (21.1) | |

| 5—total agreement | 111 (20.1) | |

| Internet used mainly for information (on a scale from 1 to 4): | ||

| 1—the most important | 180 (32.7) | |

| 2—important | 214 (38.8) | |

| 3—less important | 138 (25.0) | |

| 4—the least important | 19 (3.4) | |

| Internet used mainly for communication (on a scale from 1 to 4): | ||

| 1—the most important | 334 (60.6) | |

| 2—important | 154 (27.9) | |

| 3—less important | 58 (10.5) | |

| 4—the least important | 5 (0.9) | |

| Internet used mainly for entertainment (on a scale from 1 to 4): | ||

| 1—the most important | 183 (33.2) | |

| 2—important | 190 (34.5) | |

| 3—less important | 144 (26.1) | |

| 4—the least important | 34 (6.2) | |

| Internet used mainly for domestic facilities (on a scale from 1 to 4): | ||

| 1—the most important | 35 (6.4) | |

| 2—important | 89 (16.2) | |

| 3—less important | 143 (26.0) | |

| 4—the least important | 284 (51.5) | |

| Total | 551 (100.0) | |

References

- Basak, K.S.; Wotto, M.; Belanger, P. E-learning, M-learning and D-learning: Conceptual definition and comparative analysis. E-Learn. Digit. Media 2018, 15, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, P.; Kable, A.; Levett-Jones, T.; Booth, D. The effectiveness of internet-based e-learning on clinician behavior and patient outcomes: A systematic review protocol. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 57, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhath, S.; Dsouza, A.; Pandey, A.K.; Pandey, A.K.; Prasanna, L.C. Changing paradigms in anatomy teaching-learning during a pandemic: Modification of curricular delivery based on student perspectives. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2021, 17, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banson, J. Co-regulated learning and online learning: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2022, 6, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Baars, M.; Davis, D.; Van Der Zee, T.; Houben, G.J.; Paas, F. Supporting Self-Regulated Learning in Online Learning Environments and MOOCs: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2019, 35, 356–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Cristóbal, J.A.; Rodríguez-Triana, M.J.; Gallego-Lema, V.; Arribas-Cubero, H.F.; Asensio-Pérez, J.I.; Martínez-Monés, A. Monitoring for awareness and reflection in ubiquitous learning environments. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2018, 34, 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, I.E.; Seaman, J. Grade Level: Tracking Online Education in the United States; Babson Survey Research Group: Babson Park, FL, USA, 2015. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED572778.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Konstantinidis, K.; Apostolakis, I.; Karaiskos, P. A narrative review of e-learning in professional education of healthcare professionals in medical imaging and radiation therapy. Radiography 2022, 28, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA 2020, 323, 2131–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, M.A. E-learning in higher education institutions during COVID-19 pandemic: Current and future trends through bibliometric analysis. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, G.C.; Apfelbacher, C.; Posadzki, P.P.; Kemp, S.; Tudor Car, L. Choice of outcomes and measurement instruments in randomised trials on eLearning in medical education: A systematic mapping review protocol. Syst. Rev 2018, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, R. WFME Global Standards for Basic Medical Education—The 2012 Revision. Available online: http://www.wfme.org/news/general-news/263-standards-for-basic-medical-education-the-2012-revision (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Hew, K.F.; Cheung, W.S. Students’ and instructors’ use of massive open online courses (MOOCs): Motivations and challenges. Educ. Res. Rev. 2014, 12, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kop, R. The challenges to connectivist learning on open online networks: Learning experiences during a massive open online course. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2011, 12, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Ryu, H. Learner acceptance of a multimedia-based learning system. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2013, 29, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, J.; Poon, W.L. Self-regulated learning strategies & academic achievement in online higher education learning environments: A systematic review. Internet High. Educ. 2015, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L. What Does the “e” Stand for; Department of Science and Mathematics Education, The University of Melbourne: Melbourne, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsdottir, G.B.; Hatlevik, O.E. Newly qualified teachers’ professional digital competence: Implications for teacher education. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2018, 41, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.; Limbu, Y.B.; Bui, T.K.; Nguyen, H.T.; Pham, H.T. Does e-learning service quality influence e-learning student satisfaction and loyalty? Evidence from Vietnam. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2019, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, N.S.A.; Suradi, Z.; Yusoff, N.H. An analysis of technology acceptance model, learning management system attributes, e-satisfaction, and e-retention. Int. Rev. Manag. Bus. Res. 2014, 3, 1984–1996. [Google Scholar]

- Eom, S.B.; Ashill, N. The determinants of students’ perceived learning outcomes and satisfaction in university online education: An update. Decis. Sci. J. Innov. Educ 2016, 14, 185–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, M. Measuring student engagement in the online course: The Online Student Engagement scale (OSE). Online Learn. 2015, 19, EJ1079585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavitiyaman, P.; Ren, L.; Fung, C. Hospitality students at the online classes during COVID-19—How personality affects experience? J. Hospit. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2021, 28, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaulamie, L.A. Teaching Presence, Social Presence, and Cognitive Presence as Predictors of Students’ Satisfaction in an Online Program at a Saudi University. Ph.D. Thesis, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Peng, L.; Yin, X.; Rong, J.; Yang, J.; Cong, G. Analysis of user satisfaction with online education platforms in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare 2020, 8, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, E.; Wen, J. Applying the technology acceptance model to understand hospitality management students’ intentions to use electronic discussion boards as a learning tool. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, A.; Glore, P. The impact of design and aesthetics on usability, credibility, and learning in an online environment. Online J. Distance Learn. Adm. 2010, 13, EJ918574. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ918574 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Agyeiwaah, E.; Baiden, F.B.; Gamor, E.; Hsu, F.C. Determining the attributes that influence students’ online learning satisfaction during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Hospit. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2022, 30, 100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSporran, M.; Young, S. Does gender matter in online learning? Res. Learn. Technol. 2001, 9, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artino, A.R.; Stephens, J.M. Academic motivation and self-regulation: A comparative analysis of undergraduate and graduate students learning online. Internet High. Educ. 2009, 12, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.J.; Reinecke, K. Demographic differences in how students navigate through MOOCs. In Proceedings of the First ACM Conference on Learning@ Scale Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 4–5 March 2014; pp. 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Meinert, E.; Alturkistani, A.; Foley, K.A.; Brindley, D.; Car, J. Examining Cost Measurements in Production and Delivery of Three Case Studies Using E-Learning for Applied Health Sciences: Cross-Case Synthesis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinert, E.; Eerens, J.; Banks, C.; Maloney, S.; Rivers, G.; Ilic, D.; Walsh, K.; Majeed, A.; Car, J. Exploring the Cost of eLearning in Health Professions Education: Scoping Review. JMIR Med. Educ. 2021, 7, e13681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchi, T. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on current anatomy education and future careers: A student’s perspective. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2020, 13, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keengwe, J.; Kidd, T.T. Towards best practices in online learning and teaching in higher education. MERLOT J. Online Learn. Teach. 2010, 6, 533–541. [Google Scholar]

- Kapasia, N.; Paul, P.; Roy, A.; Saha, J.; Zaveri, A.; Mallick, R.; Barman, B.; Das, P.; Chouhan, P. Impact of lockdown on learning status of undergraduate and postgraduate students during COVID-19 pandemic in West Bengal, India. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapanta, C.; Botturi, L.; Goodyear, P.; Guardia, L.; Koole, M. Online university teaching during and after the COVID-19 crisis: Refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigit. Sci. Educ. 2020, 2, 923–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, V.; Srivastava, S. Hospitality and tourism industry amid COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives on challenges and learnings from India. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathiowetz, V.; Yu, C.H.; Quake-Rapp, C. Comparison of a gross anatomy laboratory to online anatomy software for teaching anatomy. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2016, 9, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, D.; Vincent, T.; Watson, G.; Owens, E.; Webb, R.; Gainsborough, N.; Fairclough, J.; Taylor, N.; Miles, K.; Cohen, J.; et al. Blending online techniques with traditional face to face teaching methods to deliver final year undergraduate radiology learning content. Eur. J. Radiol. 2011, 78, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.E.; Campbell, P.K.; Kimp, A.J.; Bennell, K.; Foster, N.E.; Russell, T.; Hinman, R.S. Evaluation of a Novel e-Learning Program for Physiotherapists to Manage Knee Osteoarthritis via Telehealth: Qualitative Study Nested in the PEAK (Physiotherapy Exercise and Physical Activity for Knee Osteoarthritis) Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e25872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, L.A.; Suda, K.J.; Heidel, R.E.; McDonough, S.L.K.; Hunt, M.E.; Franks, A.S. The role of online learning in pharmacy education: A nationwide survey of student pharmacists. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2020, 12, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.L.; Lin, C.C.; Chau, P.H.; Takemura, N.; Fung, J.T.C. Evaluating online learning engagement of nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 104, 104985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M.; Stowe, J.; Potocnik, J.; Giannoti, N.; Murphy, S.; Rainford, L. 3D virtual reality simulation in radiography education: The students’ experience. Radiography 2021, 27, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papamichail, D.; Pantelis, E.; Papagiannis, P.; Karaiskos, P.; Georgiou, E. A web simulation of medical image reconstruction and processing as an educational tool. J. Digit. Imaging 2015, 28, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorge, A.E.S.; Bennell, K.L.; Kimp, A.J.; Campbell, P.K.; Hinman, R.S. An e-Learning Program for Physiotherapists to Manage Knee Osteoarthritis via Telehealth During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Real-World Evaluation Study Using Registration and Survey Data. JMIR Med. Educ. 2021, 7, e30378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potu, B.K.; Atwa, H.; Nasr El-Din, W.A.; Othman, M.A.; Sarwani, N.A.; Fatima, A.; Deifalla, A.; Fadel, R.A. Learning anatomy before and during COVID-19 pandemic: Students’ perceptions and exam performance. Morphologie 2022, 106, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; He, Y.J.; Zhu, Y.H.; Dai, M.C.; Pan, M.M.; Wu, J.Q.; Zhang, X.; Gu, Y.E.; Wang, F.F.; Xu, X.R.; et al. The evaluation of online course of traditional Chinese medicine for MBBS international students during the COVID-19 epidemic period. Integr. Med. Res. 2020, 9, 100449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Srivastav, S.; Bhardwaj, A.; Dixit, A.; Misra, S. Medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A single institution experience. Indian Pediatr. 2020, 57, 678–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atwa, H.; Dafalla, S.; Kamal, D. Wet specimens, plastinated specimens, or plastic models in learning anatomy: Perception of undergraduate medical students. Med. Sci. Educ. 2021, 31, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totlis, T.; Tishukov, M.; Piagkou, M.; Kostares, M.; Natsis, K. Online educational methods vs. traditional teaching of anatomy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anat. Cell Biol. 2021, 54, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaona, A.; Banzi, R.; Kwag, K.H.; Rigon, G.; Cereda, D.; Pecoraro, V.; Tramacere, I.; Moja, L. E-learning for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 1, CD011736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, G.; Martin, C.; Ruszaj, M.; Matin, M.; Kataria, A.; Hu, J.; Brickman, A.; Elkin, P.L. How the COVID-19 Pandemic Impacted Medical Education during the Last Year of Medical School: A Class Survey. Life 2021, 11, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellano, C.; Carcamo, C. Evaluating learning of medical students through recorded lectures in clinical courses. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hani, A.B.; Hijazein, Y.; Hadadin, H.; Jarkas, A.K.; Al-Tamimi, Z.; Amarin, M.; Shatarat, A.; Abu Abeeleh, M.; Al-Taher, R. E-Learning during COVID-19 pandemic; Turning a crisis into opportunity: A cross-sectional study at The University of Jordan. Ann. Med. Surg. 2021, 70, 102882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshami, W.; Taha, M.H.; Abuzaid, M.; Saravanan, C.; Al Kawas, S.; Abdalla, M.E. Satisfaction with online learning in the new normal: Perspective of students and faculty at medical and health sciences colleges. Med. Educ. Online 2021, 26, 1920090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcha, R. Effectiveness of Virtual Medical Teaching During the COVID-19 Crisis: Systematic Review. JMIR Med. Educ. 2020, 6, e20963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanis, C.J. The seven principles of online learning: Feedback from faculty and alumni on its importance for teaching and learning. Res. Learn. Technol 2020, 28, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barteit, S.; Guzek, D.; Jahn, A.; Bärnighausen, T.; Jorge, M.M.; Neuhann, F. Evaluation of e-learning for medical education in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2020, 145, 103726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, K.; Trollor, J.; Dean, K.; Harvey, S. Medical students’ preferences regarding Psychiatry teaching: A comparison of different lecture delivery methods. MedEdPublish 2019, 8, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Smadi, A.M.; Abugabah, A.; Smadi, A.A. Evaluation of E-learning Experience in the Light of the COVID-19 in Higher Education. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 201, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.S.; Ahmed, N.; Sajjad, B.; Alshahrani, A.; Saeed, S.; Sarfaraz, S.; Alhamdan, R.S.; Vohra, F.; Abduljabbar, T. E-Learning perception and satisfaction among health sciences students amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Work 2020, 67, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chick, N. Learning Styles. Center for Teaching. Available online: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/learning-styles-preferences/ (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Shorey, S.; Chan, V.; Rajendran, P.; Ang, E. Learning styles, preferences and needs of generation Z healthcare students: Scoping review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 57, 103247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.; Shell, R.; Kassis, K.; Tartaglia, K.; Wallihan, R.; Smith, K.; Hurtubise, L.; Martin, B.; Ledford, C.; Bradbury, S.; et al. Applying adult learning practices in medical education. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2014, 44, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, A.; de Jong, P.G.M.; Drop, S.L.S.; van Kampen, S.C. A scoping review of the use of e-learning and e-consultation for healthcare workers in low- and middle-income countries and their potential complementarity. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 2022, 29, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | male | 131 (23.8) |

| female | 420 (76.2) | |

| Age group | 18–20 years | 297 (53.9) |

| 21–24 years | 158 (28.7) | |

| over 25 years | 96 (17.4) | |

| Year of study | 1 | 228 (41.4) |

| 2 | 123 (22.3) | |

| 3 | 44 (8.0) | |

| 4 | 2 (0.4) | |

| 5 | 44 (8.0) | |

| 6 | 82 (14.9) | |

| resident physician | 28 (5.1) | |

| Specialty | Dental Medicine | 262 (47.5) |

| General Medicine | 190 (34.5) | |

| Dental Technique | 70 (12.7) | |

| Assistants in Prophylactics | 1 (0.2) | |

| Orthodontics and Dental-Facial Orthopaedics | 28 (5.1) | |

| University | Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy from Iași, Romania | 356 (64.6) |

| University of Medicine and Pharmacy from Craiova, Romania | 108 (19.6) | |

| “Victor Babeș” University of Medicine and Pharmacy from Timișoara, Romania | 80 (14.5) | |

| “Iuliu Hațieganu” University of Medicine and Pharmacy from Cluj-Napoca, Romania | 7 (1.3) | |

| Previously graduated university studies | yes | 55 (10.0) |

| no | 496 (90.0) | |

| Total | 551 (100.0) |

| Recorded Answers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—Total Disagreement n (%) | 2—Partial Disagreement n (%) | 3—Neutral n (%) | 4—Partial Agreement n (%) | 5—Total Agreement n (%) | |

| Cluster 1 (n = 171–31.0% cases): | |||||

| Item 6a | 123 (71.9) | 33 (19.3) | 12 (7.0) | 3 (1.8) | - |

| Item 8a | 112 (65.5) | 42 (24.6) | 14 (8.2) | 3 (1.8) | - |

| Item 7a | 115 (67.3) | 51 (29.8) | 4 (2.3) | - | 1 (0.6) |

| Item 4a | 110 (64.3) | 53 (31.0) | 8 (4.7) | - | - |

| Item 11a | 89 (52.0) | 50 (29.2) | 19 (11.1) | 12 (7.0) | 1 (0.6) |

| Cluster 2 (n = 289–52.5% cases): | |||||

| Item 6a | 17 (5.9) | 144 (49.8) | 110 (38.1) | 18 (6.2) | - |

| Item 8a | 22 (7.6) | 118 (40.8) | 122 (42.2) | 24 (8.3) | 3 (1.0) |

| Item 7a | 23 (8.0) | 124 (42.9) | 125 (43.3) | 16 (5.5) | 1 (0.3) |

| Item 4a | 25 (8.7) | 134 (46.4) | 116 (40.1) | 14 (4.8) | - |

| Item 11a | 9 (3.1) | 69 (23.9) | 143 (49.5) | 42 (14.5) | 26 (9.0) |

| Cluster 3 (n = 91–16.5% cases): | |||||

| Item 6a | - | 1 (1.1) | 31 (34.1) | 34 (37.4) | 25 (27.5) |

| Item 8a | 1 (1.1) | 3 (3.3) | 18 (19.8) | 34 (37.4) | 35 (38.5) |

| Item 7a | - | - | 37 (40.7) | 28 (30.8) | 26 (28.6) |

| Item 4a | - | 3 (3.3) | 32 (35.2) | 37 (40.7) | 19 (20.9) |

| Item 11a | - | 1 (1.1) | 12 (13.2) | 29 (31.9) | 49 (53.8) |

| Recorded Answers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—Total Disagreement n (%) | 2—Partial Disagreement n (%) | 3—Neutral n (%) | 4—Partial Agreement n (%) | 5—Total Agreement n (%) | |

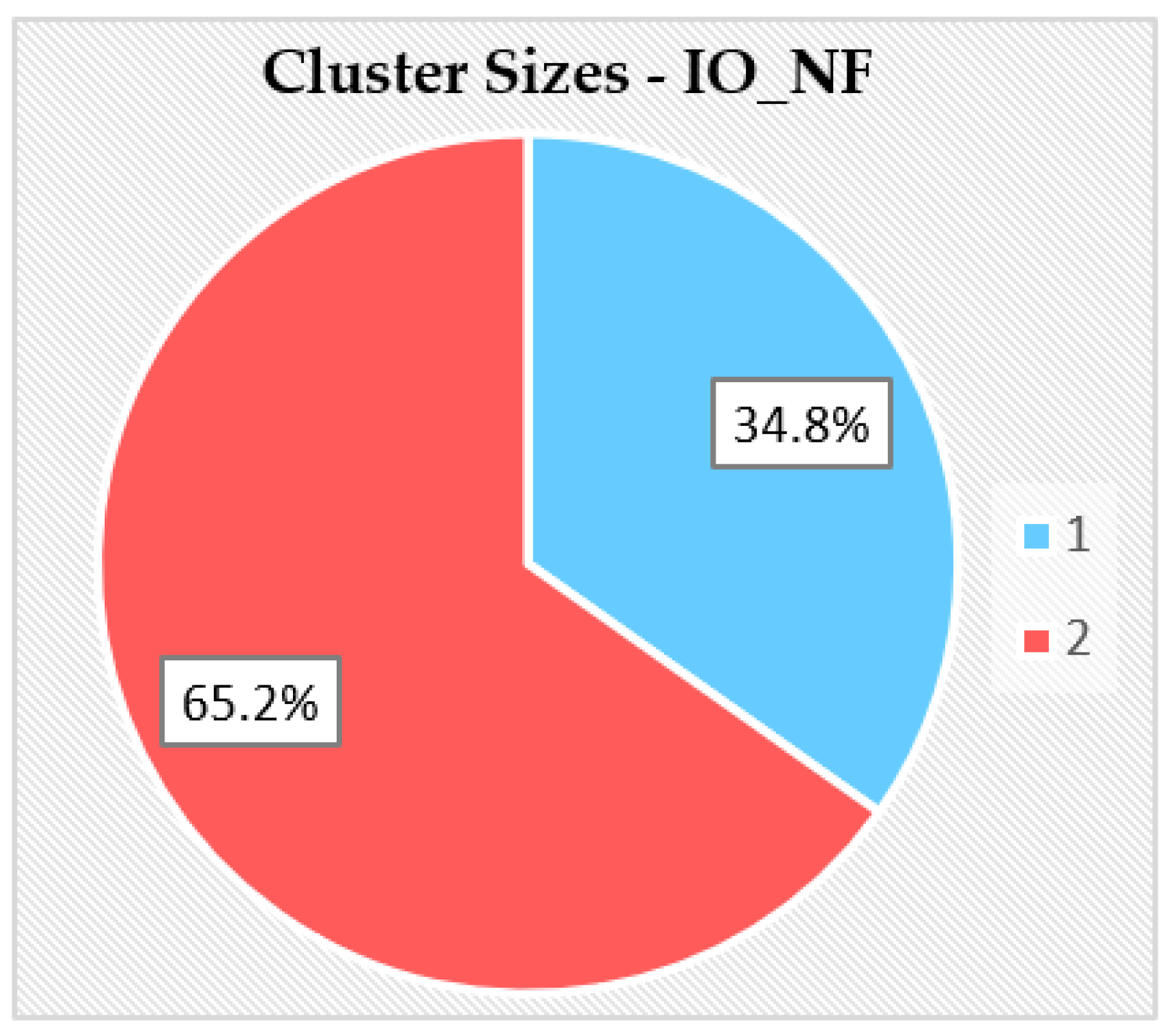

| Cluster 1 (n = 192–34.8% cases): | |||||

| Item 8b | 156 (81.3) | 17 (8.9) | 10 (5.2) | 7 (3.6) | 2 (1.0) |

| Item 9b | 142 (74.0) | 30 (15.6) | 15 (7.8) | 5 (2.6) | - |

| Item 10b | 88 (45.8) | 29 (15.1) | 41 (21.4) | 18 (9.4) | 16 (8.3) |

| Item 11b | 108 (56.3) | 45 (23.4) | 24 (12.5) | 8 (4.2) | 7 (3.6) |

| Cluster 2 (n = 359–65.2% cases): | |||||

| Item 8b | 24 (6.7) | 89 (24.8) | 121 (33.7) | 83 (23.1) | 42 (11.7) |

| Item 9b | 29 (8.1) | 108 (30.1) | 125 (34.8) | 68 (18.9) | 29 (8.1) |

| Item 10b | 2 (0.6) | 34 (9.5) | 64 (17.8) | 124 (34.5) | 135 (37.6) |

| Item 11b | 10 (2.8) | 101 (28.1) | 133 (37.0) | 70 (19.5) | 45 (12.5) |

| Generic Concept: Online Learning Transmits the Essence of Materials; Students Are More Productive and Understand the Concepts More Easily and Faster | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1—Total Disagreement n (%) | Cluster 2—Neutral or Partial Disagreement n (%) | Cluster 3—Total Agreement n (%) | p-Value | ||

| Gender | 0.476 | ||||

| Male | 43 (25.1) | 63 (21.8 | 25 (27.5) | ||

| Female | 128 (74.9) | 226 (78.2) | 66 (72.5) | ||

| Age group | 0.000 ** | ||||

| 18–20 years | 118 (69.0) | 146 (50.5) | 33 (36.3) | ||

| 21–24 years | 35 (20.5) | 87 (30.1) | 36 (39.6) | ||

| over 25 years | 18 (10.5) | 56 (19.4) | 22 (24.2) | ||

| Opinion about using multimedia resources in the learning process: | 0.000 ** | ||||

| 1—total disagreement | 17 (9.9) | 3 (1.0) | |||

| 2—partial disagreement | 53 (31.0) | 29 (10.0) | 1 (1.1) | ||

| 3—neutral | 67 (39.2) | 150 (51.9) | 4 (4.4) | ||

| 4—partial agreement | 19 (11.1) | 73 (25.3) | 24 (26.4) | ||

| 5—total agreement | 15 (8.8) | 34 (11.8) | 62 (68.1) | ||

| Internet used mainly for information (on a scale from 1 to 4): | 0.000 ** | ||||

| 1—the most important | 39 (22.8) | 90 (31.1) | 51 (56.0) | ||

| 2—important | 66 (38.6) | 128 (44.3) | 20 (22.0) | ||

| 3—less important | 58 (33.9) | 64 (22.1) | 16 (17.6) | ||

| 4—the least important | 8 (4.7) | 7 (2.4) | 4 (4.4) | ||

| Internet used mainly for communication (on a scale from 1 to 4): | 0.009 ** | ||||

| 1—the most important | 112 (65.5) | 178 (61.6) | 44 (48.4) | ||

| 2—important | 45 (26.3) | 74 (25.6) | 35 (38.5) | ||

| 3—less important | 11 (6.4) | 37 (12.8) | 10 (11.0) | ||

| 4—the least important | 3 (1.8) | 2 (2.2) | |||

| Internet used mainly for entertainment (on a scale from 1 to 4): | 0.093 | ||||

| 1—the most important | 62 (36.3) | 87 (30.1) | 34 (37.4) | ||

| 2—important | 67 (39.2) | 97 (33.6) | 26 (28.6) | ||

| 3—less important | 33 (19.3) | 83 (28.7) | 28 (30.8) | ||

| 4—the least important | 9 (5.3) | 22 (7.6) | 3 (3.3) | ||

| Internet used mainly for domestic facilities (on a scale from 1 to 4): | 0.005 ** | ||||

| 1—the most important | 7 (4.1) | 14 (4.8) | 14 (15.4) | ||

| 2—important | 27 (15.8) | 43 (14.9) | 19 (20.9) | ||

| 3—less important | 47 (27.5) | 75 (26.0) | 21 (23.1) | ||

| 4—the least important | 90 (52.6) | 157 (54.3) | 37 (40.7) | ||

| Total | 171 (100.0) | 289 (100.0) | 91 (100.0) | ||

| General Concept: Online Learning Is Lacking Monitoring and Human Interaction. The Content Is Poorly Structured; The Students Do not Have the Habit to Learn Using It | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1–Disagreement n (%) | Cluster 2–Agreement n (%) | p–Value | ||

| Gender | 0.123 | |||

| Male | 53 (27.6) | 78 (21.7) | ||

| Female | 139 (72.4) | 281 (78.3) | ||

| Age group | 0.002 ** | |||

| 18–20 years | 88 (45.8) | 209 (58.2) | ||

| 21–24 years | 57 (29.7) | 101 (28.1) | ||

| over 25 years | 47 (24.5) | 49 (13.6) | ||

| Opinion about using multimedia resources in learning process: | 0.000 ** | |||

| 1—total disagreement | 5 (2.6) | 15 (4.2) | ||

| 2—partial disagreement | 11 (5.7) | 72 (20.1) | ||

| 3—neutral | 54 (28.1) | 167 (46.5) | ||

| 4—partial agreement | 46 (24.0) | 70 (19.5) | ||

| 5—total agreement | 76 (39.6) | 35 (9.7) | ||

| Internet used mainly for information (on a scale from 1 to 4): | 0.001 ** | |||

| 1—the most important | 82 (42.7) | 98 (27.3) | ||

| 2—important | 72 (37.5) | 142 (39.6) | ||

| 3—less important | 33 (17.2) | 105 (29.2) | ||

| 4—the least important | 5 (2.6) | 14 (3.9) | ||

| Internet used mainly for communication (on a scale from 1 to 4): | 0.191 | |||

| 1—the most important | 109 (56.8) | 225 (62.7) | ||

| 2—important | 55 (28.6) | 99 (27.6) | ||

| 3—less important | 27 (14.1) | 31 (8.6) | ||

| 4—the least important | 1 (0.5) | 4 (1.1) | ||

| Internet used mainly for entertainment (on a scale from 1 to 4): | 0.039 * | |||

| 1—the most important | 66 (34.4) | 117 (32.6) | ||

| 2—important | 52 (27.1) | 138 (38.4) | ||

| 3—less important | 60 (31.3) | 84 (23.4) | ||

| 4—the least important | 14 (7.3) | 20 (5.6) | ||

| Internet used mainly for domestic facilities (on a scale from 1 to 4): | 0.011 * | |||

| 1—the most important | 16 (8.3) | 19 (5.3) | ||

| 2—important | 41 (21.4) | 48 (13.4) | ||

| 3—less important | 38 (19.8) | 105 (29.2) | ||

| 4—the least important | 97 (50.5) | 187 (52.1) | ||

| Total | 192 (100.0) | 359 (100.0) | ||

| IO_FAV (Score for Favourable Opinions) | n | Mean ± SD | Min ÷ Max | Median | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 551 | 2.950 ± 0.697 | 1.24 ÷ 5.00 | 2.882 | ||

| Gender | male | 131 | 2.956 ± 0.743 | 1.24 ÷ 5.00 | 2.882 | 0.910 † |

| female | 420 | 2.948 ± 0.683 | 1.29 ÷ 5.00 | 2.882 | ||

| Age group | 18–20 years | 297 | 2.817 ± 0.627 | 1.29 ÷ 4.88 | 2.765 | 0.000 ‡** |

| 21–24 years | 158 | 3.063 ± 0.789 | 1.24 ÷ 5.00 | 2.941 | ||

| over 25 years | 96 | 3.174 ± 0.657 | 1.94 ÷ 4.76 | 3.177 | ||

| Opinion about using multimedia resources in the learning process: | 1—total disagreement | 20 | 2.168 ± 0.486 | 1.24 ÷ 2.82 | 2.265 | 0.000 ‡** |

| 2—partial disagreement | 83 | 2.404 ± 0.440 | 1.35 ÷ 3.41 | 2.412 | ||

| 3—neutral | 221 | 2.792 ± 0.472 | 1.35 ÷ 4.12 | 2.824 | ||

| 4—partial agreement | 116 | 3.126 ± 0.528 | 1.76 ÷ 4.47 | 3.059 | ||

| 5—total agreement | 111 | 3.629 ± 0.790 | 2.00 ÷ 5.00 | 3.647 | ||

| Internet used mainly for information: | 1—the most important | 180 | 3.180 ± 0.783 | 1.24 ÷ 5.00 | 3.088 | 0.000 ‡** |

| 2—important | 214 | 2.878 ± 0.591 | 1.29 ÷ 5.00 | 2.882 | ||

| 3—less important | 138 | 2.772 ± 0.659 | 1.35 ÷ 4.59 | 2.706 | ||

| 4—the least important | 19 | 2.873 ± 0.684 | 1.94 ÷ 3.88 | 2.765 | ||

| Internet used mainly for communication: | 1—the most important | 334 | 2.916 ± 0.685 | 1.24 ÷ 5.00 | 2.853 | 0.224 ‡ |

| 2—important | 154 | 2.989 ± 0.764 | 1.35 ÷ 5.00 | 2.941 | ||

| 3—less important | 58 | 3.045 ± 0.542 | 1.59 ÷ 4.12 | 3.059 | ||

| 4—the least important | 5 | 2.882 ± 0.997 | 2.00 ÷ 4.18 | 2.471 | ||

| Internet used mainly for entertainment: | 1—the most important | 183 | 2.987 ± 0.734 | 1.35 ÷ 4.88 | 2.941 | 0.063 ‡ |

| 2—important | 190 | 2.844 ± 0.669 | 1.24 ÷ 4.76 | 2.765 | ||

| 3—less important | 144 | 3.053 ± 0.700 | 1.29 ÷ 5.00 | 2.941 | ||

| 4—the least important | 34 | 2.907 ± 0.567 | 1.71 ÷ 4.12 | 2.941 | ||

| Internet used mainly for domestic facilities: | 1—the most important | 35 | 3.335 ± 0.904 | 1.35 ÷ 4.88 | 3.235 | 0.005 ‡** |

| 2—important | 89 | 3.060 ± 0.731 | 1.47 ÷ 5.00 | 3.000 | ||

| 3—less important | 143 | 2.856 ± 0.687 | 1.24 ÷ 4.76 | 2.824 | ||

| 4—the least important | 284 | 2.915 ± 0.645 | 1.35 ÷ 5.00 | 2.882 | ||

| Two-Step Clustering | Cluster 1 | 171 | 2.228 ± 0.336 | 1.24 ÷ 2.82 | 2.294 | 0.000 ‡** |

| Cluster 2 | 289 | 3.022 ± 0.291 | 2.41 ÷ 3.76 | 3.000 | ||

| Cluster 3 | 91 | 4.076 ± 0.445 | 3.24 ÷ 5.00 | 4.000 | ||

| IO_NF (Score for Not Favourable Opinions) | n | Mean ± SD | Min ÷ Max | Median | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 551 | 2.392 ± 0.794 | 1.00 ÷ 4.64 | 2.429 | ||

| Gender | male | 131 | 2.308 ± 0.803 | 1.00 ÷ 4.57 | 2.286 | 0.111 † |

| female | 420 | 2.418 ± 0.790 | 1.00 ÷ 4.64 | 2.500 | ||

| Age group | 18–20 years | 297 | 2.521 ± 0.781 | 1.00 ÷ 4.64 | 2.571 | 0.000 ‡** |

| 21–24 years | 158 | 2.332 ± 0.776 | 1.00 ÷ 4.21 | 2.357 | ||

| over 25 years | 96 | 2.090 ± 0.776 | 1.00 ÷ 3.79 | 2.071 | ||

| Opinion about using multimedia resources in the learning process: | 1—total disagreement | 20 | 2.950 ± 0.852 | 1.50 ÷ 4.64 | 3.000 | 0.000 ‡** |

| 2—partial disagreement | 83 | 2.806 ± 0.662 | 1.50 ÷ 4.29 | 2.857 | ||

| 3—neutral | 221 | 2.511 ± 0.686 | 1.00 ÷ 4.43 | 2.500 | ||

| 4—partial agreement | 116 | 2.270 ± 0.742 | 1.00 ÷ 4.14 | 2.286 | ||

| 5—total agreement | 111 | 1.871 ± 0.821 | 1.00 ÷ 4.57 | 1.714 | ||

| Internet used mainly for information: | 1—the most important | 180 | 2.262 ± 0.873 | 1.00 ÷ 4.64 | 2.214 | 0.019 ‡* |

| 2—important | 214 | 2.398 ± 0.783 | 1.00 ÷ 4.43 | 2.393 | ||

| 3—less important | 138 | 2.542 ± 0.656 | 1.00 ÷ 4.14 | 2.571 | ||

| 4—the least important | 19 | 2.455 ± 0.876 | 1.00 ÷ 4.00 | 2.714 | ||

| Internet used mainly for communication: | 1—the most important | 334 | 2.426 ± 0.790 | 1.00 ÷ 4.64 | 2.500 | 0.195 ‡ |

| 2—important | 154 | 2.356 ± 0.822 | 1.00 ÷ 4.43 | 2.429 | ||

| 3—less important | 58 | 2.255 ± 0.729 | 1.00 ÷ 4.14 | 2.286 | ||

| 4—the least important | 5 | 2.814 ± 0.714 | 1.71 ÷ 3.57 | 3.000 | ||

| Internet used mainly for entertainment: | 1—the most important | 183 | 2.329 ± 0.827 | 1.00 ÷ 4.64 | 2.357 | 0.000 ‡** |

| 2—important | 190 | 2.558 ± 0.760 | 1.00 ÷ 4.43 | 2.643 | ||

| 3—less important | 144 | 2.207 ± 0.748 | 1.00 ÷ 4.00 | 2.214 | ||

| 4—the least important | 34 | 2.580 ± 0.794 | 1.00 ÷ 4.29 | 2.429 | ||

| Internet used mainly for domestic facilities: | 1—the most important | 35 | 2.145 ± 0.948 | 1.00 ÷4.57 | 2.000 | 0.002 ‡** |

| 2—important | 89 | 2.204 ± 0.902 | 1.00 ÷ 4.64 | 2.143 | ||

| 3—less important | 143 | 2.564 ± 0.779 | 1.00 ÷ 4.29 | 2.571 | ||

| 4—the least important | 284 | 2.394 ± 0.724 | 1.00 ÷ 4.43 | 2.429 | ||

| Two-Step Clustering | Cluster 1 | 192 | 1.541 ± 0.420 | 1.00 ÷ 2.79 | 1.500 | 0.000 †** |

| Cluster 2 | 359 | 2.847 ± 0.526 | 1.86 ÷ 4.64 | 2.857 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dascalu, C.G.; Antohe, M.E.; Topoliceanu, C.; Purcarea, V.L. Medicine Students’ Opinions Post-COVID-19 Regarding Online Learning in Association with Their Preferences as Internet Consumers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3549. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043549

Dascalu CG, Antohe ME, Topoliceanu C, Purcarea VL. Medicine Students’ Opinions Post-COVID-19 Regarding Online Learning in Association with Their Preferences as Internet Consumers. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3549. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043549

Chicago/Turabian StyleDascalu, Cristina Gena, Magda Ecaterina Antohe, Claudiu Topoliceanu, and Victor Lorin Purcarea. 2023. "Medicine Students’ Opinions Post-COVID-19 Regarding Online Learning in Association with Their Preferences as Internet Consumers" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3549. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043549

APA StyleDascalu, C. G., Antohe, M. E., Topoliceanu, C., & Purcarea, V. L. (2023). Medicine Students’ Opinions Post-COVID-19 Regarding Online Learning in Association with Their Preferences as Internet Consumers. Sustainability, 15(4), 3549. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043549