“Quiet the Mind, and the Soul Will Speak”! Exploring the Boundary Effects of Green Mindfulness and Spiritual Intelligence on University Students’ Green Entrepreneurial Intention–Behavior Link

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Green Entrepreneurship: An Overview

2.2. Self-Determination Theory

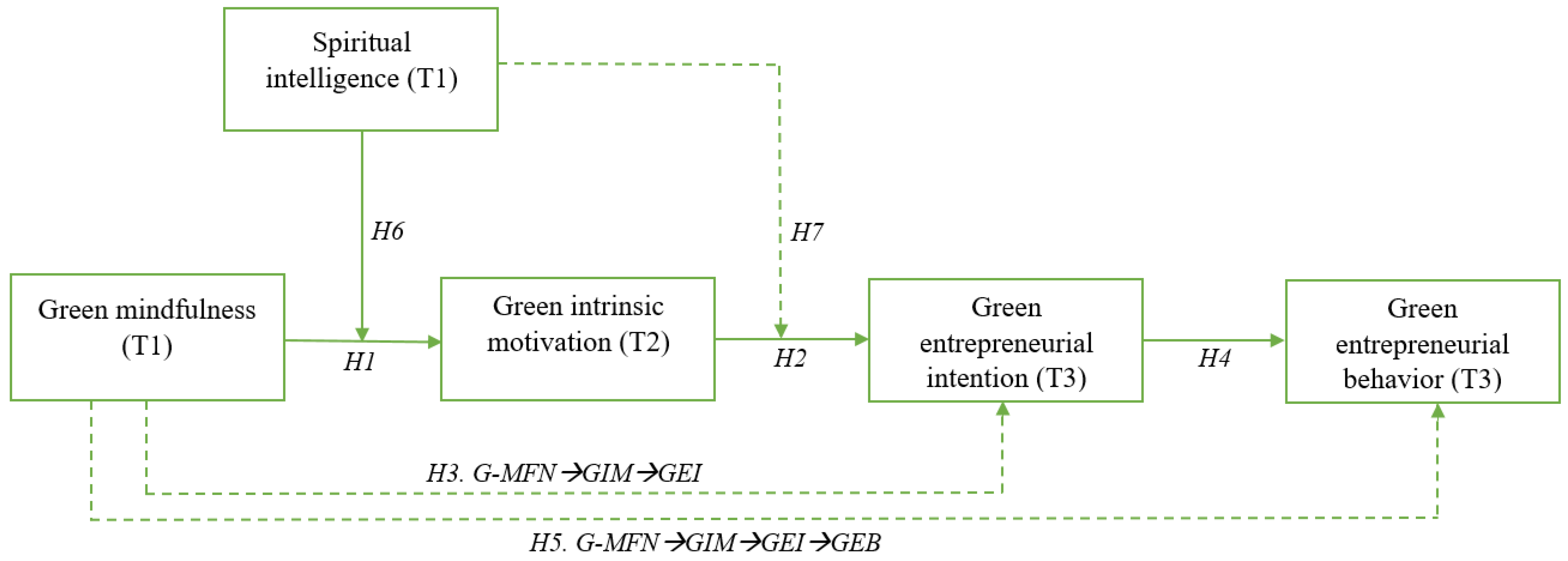

2.3. Hypotheses

2.3.1. Green Mindfulness and Green Intrinsic Motivation

2.3.2. Green Intrinsic Motivation and Green Entrepreneurial Intention

2.3.3. The Mediating Role of Green Intrinsic Motivation

2.3.4. Green Entrepreneurial Intention and Green Entrepreneurial Behavior

2.3.5. Serial Mediator Effects of Green Intrinsic Motivation and Green Entrepreneurial Intention

2.3.6. Moderator Effect of Spiritual Intelligence

- Critical existential thinking—“Ability to think critically about the truth and essence of the universe, time, life, death and other metaphysical or existential issues”;

- Personal meaning production—“Ability to create personal intentions, purpose and direction in all mental experiences including the capability to establish and implement the purpose of life”;

- Transcendental awareness—“Ability to recognize and understand the superior and transcendental dimensions and aspects of self, others and the world in waking life and consciousness”;

- Conscious state expansion—“Ability to enter higher levels of spiritual and beyond consciousness states of mind and exiting from at will”.

2.3.7. Moderated Mediation Model

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Control Variables

4. Result

4.1. Measurement Model

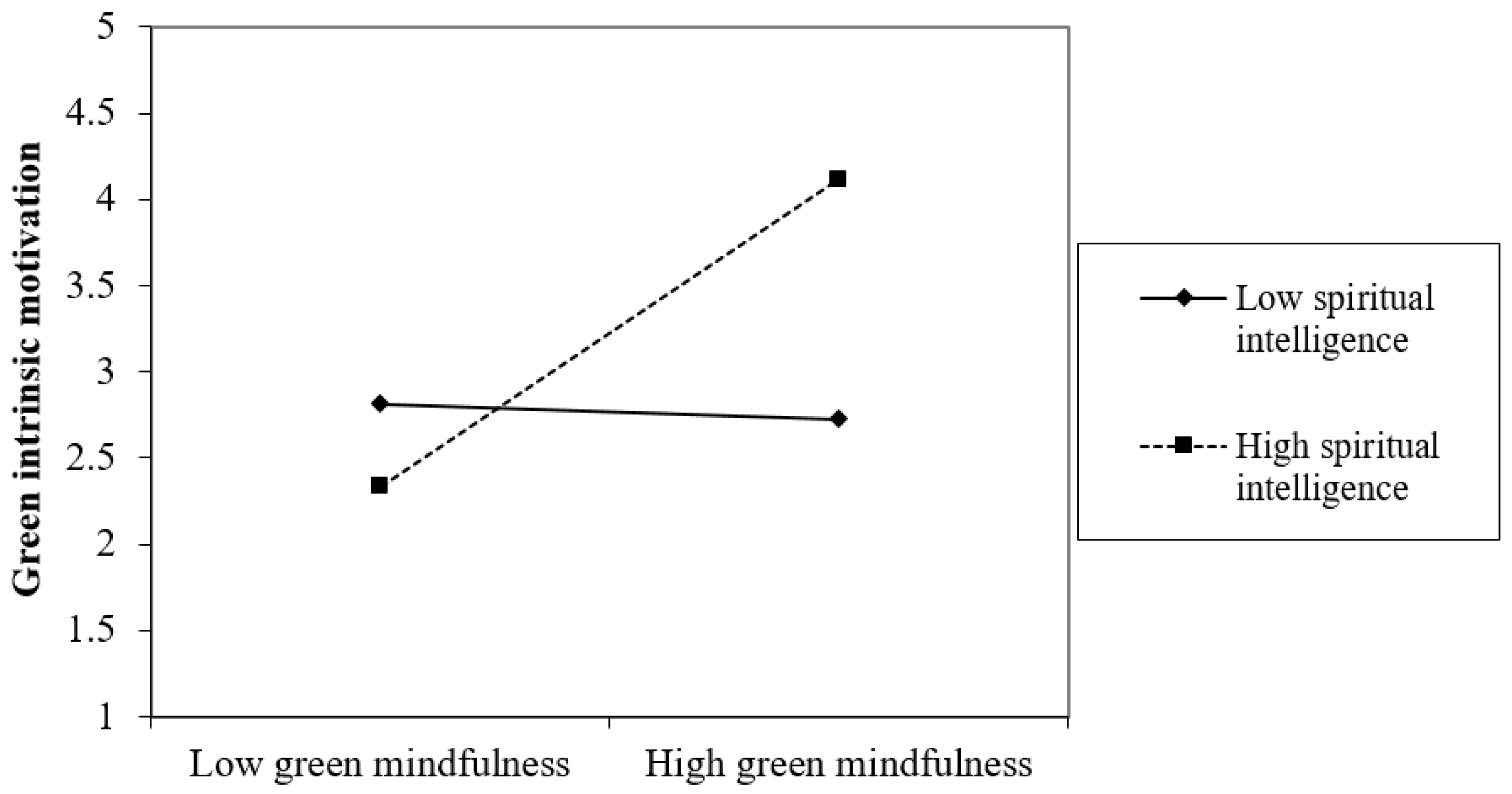

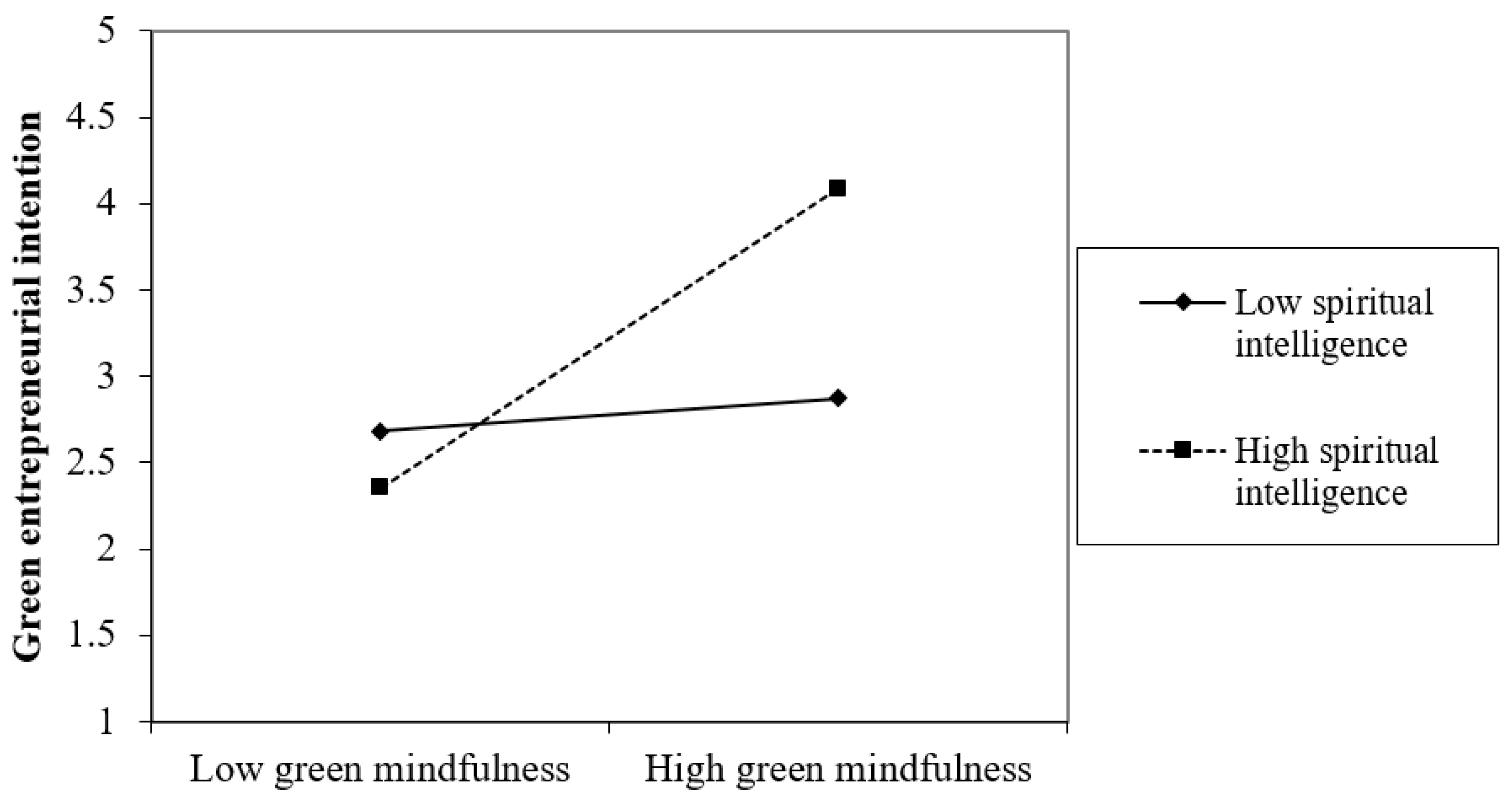

4.2. Structural Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications for Theory

5.2. Implications for Practice

5.3. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire

- (1)

- I feel free to discuss environmental issues and problems.

- (2)

- I am encouraged to express different views concerning environmental issues and problems.

- (3)

- I pay attention to what is happening if unexpected environmental issues and problems arise.

- (4)

- I am inclined to report environmental information and knowledge that have significant consequences.

- (5)

- I am rewarded if I share and announce new environmental information and knowledge.

- (6)

- I know what is readily available for consultation if unexpected environmental issues and problems arise.

- (1)

- I enjoy coming up with new green ideas.

- (2)

- I enjoy trying to solve environmental tasks.

- (3)

- I enjoy tackling environmental tasks that are completely new.

- (4)

- I enjoy improving existing green ideas.

- (5)

- I feel excited when I have new green ideas.

- (6)

- I feel like becoming further engaged in the development of green ideas.

- (1)

- I am ready to do anything to be an entrepreneur who promotes environmentalism.

- (2)

- My professional goal is to be a green entrepreneur.

- (3)

- I will make every effort to start and run my own venture that promotes environmentalism.

- (4)

- I am very determined to create a venture that promotes environmentalism in the future.

- (5)

- I have very seriously thought of starting a firm that promotes environmentalism in some way.

- (6)

- I have the firm intention to start a green venture someday.

- (1)

- I have written a green business plan.

- (2)

- I have started green product/service development.

- (3)

- I have attempted to obtain external funding.

- (4)

- I have purchased material equipment or machinery.

- (1)

- I have often questioned or pondered the nature of reality.

- (2)

- I recognize aspects of myself that are deeper than my physical body.

- (3)

- I have spent time contemplating the purpose or reason for my existence.

- (4)

- I am able to enter higher states of consciousness or awareness.

- (5)

- I am able to deeply contemplate what happens after death.

- (6)

- It is difficult for me to sense anything other than the physical and material. (R)

- (7)

- My ability to find meaning and purpose in life helps me adapt to stressful situations.

- (8)

- I can control when I enter higher states of consciousness or awareness.

- (9)

- I have developed my own theories about such things as life, death, reality, and existence.

- (10)

- I am aware of a deeper connection between myself and other people.

- (11)

- I am able to define a purpose or reason for my life.

- (12)

- I am able to move freely between levels of consciousness or awareness.

- (13)

- I frequently contemplate the meaning of events in my life.

- (14)

- I define myself by my deeper, non-physical self.

- (15)

- When I experience a failure I am still able to find meaning in it.

- (16)

- I often see issues and choices more clearly while in higher states of consciousness/ awareness.

- (17)

- I have often contemplated the relationship between human beings and the rest of the universe.

- (18)

- I am highly aware of the nonmaterial aspects of life.

- (19)

- I am able to make decisions according to my purpose in life.

- (20)

- I recognize qualities in people which are more meaningful than their body, personality, or emotions.

- (21)

- I have deeply contemplated whether or not there is some greater power or force (e.g., god, goddess, divine being, higher energy, etc.).

- (22)

- Recognizing the nonmaterial aspects of life helps me feel centered.

- (23)

- I am able to find meaning and purpose in my everyday experiences.

- (24)

- I have developed my own techniques for entering higher states of consciousness or awareness.

References

- Bergset, L.; Fichter, K. Green start-ups–a new typology for sustainable entrepre-neurship and innovation research. J. Innov. Manag. 2015, 3, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundel, R.; Hampton, S. Eco-Innovation and Green Start-Ups: An Evidence Review; Enterprise Research Centre: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cojoianu, T.F.; Clark, G.L.; Hoepner, A.G.; Veneri, P.; Wójcik, D. Entrepreneurs for a low carbon world: How environmental knowledge and policy shape the creation and financing of green start-ups. Res. Policy 2020, 49, 103988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, G.; Hottenrott, H. Green start-ups and the role of founder personality. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2022, 17, e00316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, C.; Kittler, M. Removing environmental market failure through support mechanisms: Insights from green start-ups in the British, French and German energy sectors. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 52, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, N.H.; Hiep, P.M.; Dai, N.Q.; Duc, N.M.; Hong, T.T.K. Green entrepreneurship understanding in Vietnam. Int. J. Entrep. 2020, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Amankwah, J.; Sesen, H. On the relation between green entrepreneurship intention and behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Risco, A.; Mlodzianowska, S.; García-Ibarra, V.; Rosen, M.A.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S. Factors affecting green entrepreneurship intentions in business university students in COVID-19 pandemic times: Case of Ecuador. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, B.A.; Ghumro, I.A.; Shah, N. Green entrepreneurship inclination among the younger generation: An avenue towards a green economy. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Bhutto, T.A.; Xuhui, W.; Maitlo, Q.; Zafar, A.U.; Bhutto, N.A. Unlocking employees’ green creativity: The effects of green transformational leadership, green intrinsic, and extrinsic motivation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, G. From green entrepreneurial intentions to green entrepreneurial behaviors: The role of university entrepreneurial support and external institutional support. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, B.S.; Fethi, A.; Djaoued, O.B. The influence of attitude, subjective norms and perceived behavior control on entrepreneurial intentions: Case of Algerian students. Am. J. Econ. 2017, 7, 274–282. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Khattak, M.S.; Anwar, M. Personality traits and entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of risk aversion. J. Public Aff. 2022, 22, e2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, R.; Kumar, R.; Datta, M.; Kumar, R.K.; Kumar, P. How does perceived desirability and perceived feasibility effects the entrepreneurial intention. In Electronic Systems and Intelligent Computing; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 607–616. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Yeh, S.L.; Cheng, H.I. Green shared vision and green creativity: The mediation roles of green mindfulness and green self-efficacy. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesharaki, F. Entrepreneurial passion, self-efficacy, and spiritual intelligence among Iranian SME owner–managers. Psychol. Stud. 2019, 64, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, A.E.; Settles, A.; Shen, T. Does family support matter? The influence of support factors on entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions of college students. Acad. Entrep. J. 2017, 23, 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, I.; Zaman, U.; Waris, I.; Shafique, O. A serial-mediation model to link entrepreneurship education and green entrepreneurial behavior: Application of resource-based view and flow theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M. A theory of reasoned action: Some applications and implications. Neb. Symp. Motiv. 1979, 27, 65–116. [Google Scholar]

- Olugbara, C.T.; Imenda, S.N.; Olugbara, O.O.; Khuzwayo, H.B. Moderating effect of innovation consciousness and quality consciousness on intention-behaviour relationship in E-learning integration. Educ Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Conceptualizations of intrinsic motivation and self-determination. In Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1985; pp. 11–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, P.; Li, Q.C.; Rentocchini, F.; Tamvada, J.P. Born to be green: New insights into the economics and management of green entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 52, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapp, C.T.; Kanbach, D.K. Green entrepreneurship and business models: Deriving green technology business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blue, J. Ecopreneuring: Managing for Results; Scott Foresman: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, S.J. Ecopreneuring: The Complete Guide to Small Business Opportunities from the Environmental Revolution; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gast, J.; Gundolf, K.; Cesinger, B. Doing business in a green way: A systematic review of the ecological sustainability entrepreneurship literature and future research directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzyńska, D.; Jabłońska, M.; Dziuba, R. Opportunities and conditions for the development of green entrepreneurship in the polish textile sector. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2018, 26, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.A.; Zedler, J.B.; Falk, D.A. Ecological theory and restoration ecology. In Foundations of Restoration Ecology; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jubari, I.; Hassan, A.; Liñán, F. Entrepreneurial intention among University students in Malaysia: Integrating self-determination theory and the theory of planned behavior. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 1323–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.K.; Chai, C.S. Sustainable curriculum planning for artificial intelligence education: A self-determination theory perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination Theory. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 21, pp. 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination. In Reference Module in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 11, pp. 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C.; Malycha, C.P.; Schafmann, E. The influence of intrinsic motivation and synergistic extrinsic motivators on creativity and innovation. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amabile, T.M. Componential Theory of Creativity; Working Paper 12-096. In Encyclopedia of Management Theory; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.D. Mindfulness interventions. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2017, 68, 491–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glomb, T.M.; Duffy, M.K.; Bono, J.E.; Yang, T. Mindfulness at work. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kroon, B.; van Woerkom, M.; Menting, C. Mindfulness as substitute for transformational leadership. J. Manag. Psychol. 2017, 32, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neace, S.M.; Hicks, A.M.; DeCaro, M.S.; Salmon, P.G. Trait mindfulness and intrinsic exercise motivation uniquely contribute to exercise self-efficacy. J. Am. Coll. Health 2020, 70, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffault, A.; Bernier, M.; Juge, N.; Fournier, J.F. Mindfulness may moderate the relationship between intrinsic motivation and physical activity: A cross-sectional study. Mindfulness 2016, 7, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Pei, H.; Kunpeng, X. Can entrepreneurial opportunities really help entrepreneurship intention? A study based on mixing effect of entrepreneurship self-efficacy and perceived risk. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2011, 5, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; An, L.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, P. The role of entrepreneurship policy in college students’ entrepreneurial intention: The intermediary role of entrepreneurial practice and entrepreneurial spirit. Front Psychol. 2021, 12, 585698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.J.; Yuan, C.H.; Chen, M.Y. Understanding Startups: From Idea to Market. Front Psychol. 2022, 13, 876172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junsheng, H.; Masud, M.M.; Akhtar, R.; Rana, M.S. The mediating role of employees’ green motivation between exploratory factors and green behaviour in the Malaysian food industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamini, R.; Soloveva, D.; Peng, X. What inspires social entrepreneurship? The role of prosocial motivation, intrinsic motivation, and gender in forming social entrepreneurial intention. Entrep. Res. J. 2020, 12, 71–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A. A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 907–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Liñán, F.; Moriano, J.A. Beyond entrepreneurial intentions: Values and motivations in entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2014, 10, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNoble, A.F.; Jung, D.; Ehrlich, S.B. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: The development of a measure and its relationship to entrepreneurial action. In Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research 1999: Proceedings of the 19th Annual Entrepreneurship Research Conference; Babson College: Babson Park, MA, USA, 1999; pp. 73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, N.F., Jr.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T.; Hatak, I.; Kibler, E.; Wainwright, T. Emergence of entrepreneurial behaviour: The role of age-based self-image. J. Econ. Psychol. 2015, 50, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelderen, M.V.; Kautonen, T.; Fink, M. From entrepreneurial intentions to actions: Self-control and action-related doubt, fear, and aversion. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, D. Spiritual Intelligence: The Ultimate Intelligence; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandaran, S.D.; Krauss, S.E.; Krauss, S.E.; Hamzah, A.; Hamzah, A.; Idris, K. Effectiveness of the use of spiritual intelligence in women academic leadership practice. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2017, 31, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.B.; DeCicco, T.L. A viable model and self-report measure of spiritual intelligence. Int. J. Transpers. Stud. 2009, 28, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Westhuizen, T.; Goyayi, M.J. The influence of technology on entrepreneurial self-efficacy development for online business start-up in developing nations. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2020, 21, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmié, M.; Boehm, J.; Friedrich, J.; Parida, V.; Wincent, J.; Kahlert, J.; Gassmann, O.; Sjödin, D. Start-ups versus incumbents in ‘green’industry transformations: A comparative study of business model archetypes in the electrical power sector. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 96, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayah, T.; Rahman, S.A.; Taghizadeh, S.K. Modelling green entrepreneurial intention among university students using the entrepreneurial event and cultural values theory. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2019, 11, 394–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.A.; Maxwell, S.E. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003, 112, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.E.; Cole, D.A. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanm, M.U.; Ayubm, A. Women’s experience of perceived uncertainty: Insights from emotional intelligence. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 34, 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahabuddin, M.; Tan, Q.; Ayub, A.; Fatima, T.; Ishaq, M.; Khan, A.J. Workplace ostracism and employee silence: An identity-based perspective. Kybernetes 2023, 52, 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Ayub, A.; Ishaq, M.; Arif, S.; Fatima, T.; Sohail, H.M. Workplace ostracism and employee silence in service organizations: The moderating role of negative reciprocity beliefs. Int. J. Manpow. 2022, 43, 1378–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, A.; Sultana, F.; Iqbal, S.; Abdullah, M.; Khan, N. Coping with workplace ostracism through ability-based emotional intelligence. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2021, 34, 969–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.J.; Seaman, A.E. Corporate governance and mindfulness: The impact of management accounting systems change. J. App. Bus. Res. 2010, 26, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Hill, K.G.; Hennessey, B.A.; Tighe, E.M. The Work Preference Inventory: Assessing intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y.W. Development and cross–cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Market Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Fassot, G. Testing moderating effects in PLS models: An illustration of available procedures. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications in Marketing and Related Fields; VinziV, E., ChinW, W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, J.F. Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.M.; Lauro, C. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, A.; Birnbrich, C. The impact of fraud prevention on bank-customer relationships: An empirical investigation in retail banking. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2012, 30, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lin, C.; Zhao, G.; Zhao, D. Research on the effects of entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial self-efficacy on college students’ entrepreneurial intention. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molaei, R.; Zali, M.R.; Mobaraki, M.H.; Farsi, J.Y. The impact of entrepreneurial ideas and cognitive style on students’ entrepreneurial intention. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2014, 6, 140–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Gao, F. An investigation of the influence of intrinsic motivation on students’ intention to use mobile devices in language learning. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 1181–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyar, M.N.; Ali, F.; Shafique, I. Green mindfulness and green creativity nexus in hospitality industry: Examining the effects of green process engagement and CSR. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 2653–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, Z.; Kausar, S.; Kannaiah, D.; Shabbir, M.S.; Khan, G.Y.; Zamir, A. The mediating role of green creativity and the moderating role of green mindfulness in the relationship among clean environment, clean production, and sustainable growth. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 29, 13238–13252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Ashfaq, M.; Begum, S.; Ali, A. How “Green” thinking and altruism translate into purchasing intentions for electronics products: The intrinsic-extrinsic motivation mechanism. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 24, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational citizenship behavior: Recent trends and developments. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danley, J.V. Ethical behavior for today’s workplace. Coll. Univ. 2006, 81, 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, S.; Polania-Reyes, S. Economic incentives and social preferences: Substitutes or complements? J. Econ. Lit. 2012, 50, 368–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M. Entrepreneurial creativity through motivational synergy. J. Creat. Behav. 1997, 31, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.; Martins, J.M.; Mata, P.N.; Tian, H.; Naz, S.; Dâmaso, M.; Santos, R.S. Assessing the relationship between market orientation and green product innovation: The intervening role of green self-efficacy and moderating role of resource bricolage. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.T.; Mackay, C.M.; Droogendyk, L.M.; Payne, D. What predicts environmental activism? The roles of identification with nature and politicized environmental identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 61, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| G-MFN | GIM | GEI | GEB | SI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-MFN | 1.250 | ||||

| GIM | 3.577 | ||||

| GEI | 1.000 | ||||

| GEB | |||||

| SI | 1.111 | 3.212 |

| Loadings | AVE | CR | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green mindfulness | 0.557 | 0.882 | 0.846 | |

| G-MFN1 | 0.767 | |||

| G-MFN2 | 0.792 | |||

| G-MFN3 | 0.753 | |||

| G-MFN4 | 0.741 | |||

| G-MFN5 | 0.689 | |||

| G-MFN6 | 0.734 | |||

| Green intrinsic motivation | 0.541 | 0.912 | 0.864 | |

| GIM1 | 0.771 | |||

| GIM2 | 0.812 | |||

| GIM3 | 0.700 | |||

| GIM4 | 0.654 | |||

| GIM5 | 0.765 | |||

| GIM6 | 0.688 | |||

| Green entrepreneurial intention | 0.580 | 0.890 | 0.853 | |

| GEI1 | 0.783 | |||

| GEI2 | 0.802 | |||

| GEI3 | 0.681 | |||

| GEI4 | 0.724 | |||

| GEI5 | 0.799 | |||

| Green entrepreneurial behavior | 0.514 | 0.912 | 0.867 | |

| GEB1 | 0.715 | |||

| GEB2 | 0.627 | |||

| GEB3 | 0.810 | |||

| GEB4 | 0.704 | |||

| Spiritual intelligence | 0.554 | 0.882 | 0.840 | |

| SI1 | 0.710 | |||

| SI2 | 0.692 | |||

| SI3 | 0.774 | |||

| SI4 | 0.684 | |||

| SI5 | 0.813 | |||

| SI6 | 0.753 | |||

| SI8 | 0.756 | |||

| SI9 | 0.634 | |||

| SI10 | 0.788 | |||

| SI12 | 0.732 | |||

| SI13 | 0.748 | |||

| SI14 | 0.705 | |||

| SI15 | 0.804 | |||

| SI16 | 0.723 | |||

| SI17 | 0.699 | |||

| SI18 | 0.784 | |||

| SI19 | 0.765 | |||

| SI20 | 0.724 | |||

| SI21 | 0.812 | |||

| SI22 | 0.784 | |||

| SI23 | 0.734 | |||

| SI24 | 0.729 |

| G-MFN | GIM | GEI | GEB | SI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-MFN | 0.746 | ||||

| GIM | 0.542 | 0.735 | |||

| GEI | 0.245 | 0.434 | 0.762 | ||

| GEB | 0.523 | 0.652 | 0.452 | 0.720 | |

| SI | 0.510 | 0.534 | 0.373 | 0.475 | 0.744 |

| G-MFN | GIM | GEI | GEB | SI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-MFN | |||||

| GIM | 0.727 CI.0.900 [0.678; 0.770] | ||||

| GEI | 0.700 CI.0.900 [0.634; 0.767] | 0.670 CI.0.900 [0.621; 0.742] | |||

| GEB | 0.665 CI.0.900 [0.590; 0.712] | 0.576 CI.0.900 [0.504; 0.632] | 0.627 CI.0.900 [0.560; 0.678] | ||

| SI | 0.723 CI.0.900 [0.664; 0.788] | 0.672 CI.0.900 [0.603; 0.735] | 0.576 CI.0.900 [0.498; 0.652] | 0.527 CI.0.900 [0.441; 0.592] |

| Hypotheses | β | CI (5%, 95%) | SE | t-Value | p-Value | Decision | f2 | R2 | Q2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 1 | 0.052 (n.s.) | (−0.041, 0.094) | 0.011 | 0.421 | 0.446 | ||||

| Gender 2 | 0.099 (n.s.) | (−0.030, 0.172) | 0.020 | 0.683 | 0.741 | ||||

| Education 3 | 0.051 (n.s.) | (−0.033, 0.087) | 0.031 | 0.338 | 0.354 | ||||

| Income 4 | 0.012 (n.s.) | (−0.044, 0.086) | 0.028 | 1.113 | 0.190 | ||||

| H1 G-MFN → GIM | 0.424 *** | (0.354, 0.492) | 0.052 | 7.071 | 0.001 | Supported | 0.312 | 0.524 | 0.462 |

| H2 GIM → GEI | 0.482 *** | (0.423, 0.554) | 0.050 | 10.895 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.424 | 0.499 | 0.344 |

| H4 GEI → GEB | 0.512 *** | (0.451, 0.580) | 0.048 | 8.789 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.218 | 0.570 | 0.214 |

| H6 G-MFN × SI → GIM | 0.468 *** | (0.390, 0.523) | 0.072 | 12.329 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.221 | ||

| H7 G-MFN × SI → GEI | 0.386 *** | (0.327, 0.452) | 0.042 | 9.422 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.187 |

| Path | t-Value | 95% BCCI | Path | t-Value | 95% BCCI | Decision | VAF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect G-MFN → GEI | 0.314 | 5.218 | (0.264, 0.370) | Indirect effect G-MFN → GIM → GEI | 0.288 | 4.311 | (0.224, 0.338) | Supported | 47.84% |

| G-MFN → GEB | 0.428 | 6.232 | (0.372, 0.470) | G-MFN → GIM → GEI → GEB | 0.297 | 3.230 | (0.237, 0.352) | Supported | 40.96% |

| Constructs | AVE | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| G-MFN | 0.557 | |

| GIM | 0.541 | |

| GEI | 0.580 | 0.524 |

| GEB | 0.514 | 0.499 |

| SI | 0.554 | 0.570 |

| Average scores | 0.549 | 0.531 |

| (GFI = ) | 0.539 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cai, B.; Chen, Y.; Ayub, A. “Quiet the Mind, and the Soul Will Speak”! Exploring the Boundary Effects of Green Mindfulness and Spiritual Intelligence on University Students’ Green Entrepreneurial Intention–Behavior Link. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15053895

Cai B, Chen Y, Ayub A. “Quiet the Mind, and the Soul Will Speak”! Exploring the Boundary Effects of Green Mindfulness and Spiritual Intelligence on University Students’ Green Entrepreneurial Intention–Behavior Link. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):3895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15053895

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Binbin, Yin Chen, and Arslan Ayub. 2023. "“Quiet the Mind, and the Soul Will Speak”! Exploring the Boundary Effects of Green Mindfulness and Spiritual Intelligence on University Students’ Green Entrepreneurial Intention–Behavior Link" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 3895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15053895

APA StyleCai, B., Chen, Y., & Ayub, A. (2023). “Quiet the Mind, and the Soul Will Speak”! Exploring the Boundary Effects of Green Mindfulness and Spiritual Intelligence on University Students’ Green Entrepreneurial Intention–Behavior Link. Sustainability, 15(5), 3895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15053895